Homology Modeling, Molecular Docking, and Molecular Dynamic Simulation of the Binding Mode of PA-1 and Botrytis cinerea PDHc-E1①

RAO Di HE Jun-Bo② FENG Jing-To ZHANG Wei-Nong CAI Meng HE Hong-Wu②

a (Key Laboratory for Deep Processing of Major Grain and Oil, Ministry of Education,College of Food Science & Engineering, Wuhan Polytechnic University, Wuhan 430023, China)b (Key Laboratory of Pesticide & Chemical Biology, Ministry of Education,Department of Chemistry, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China)

ABSTRACT To reveal the potential fungicidal mechanism of 5-((4-((4-chlorophenoxy)methyl)-5-iodo-1H-1,2,3-triazole-1-yl)methyl)-2-methylpyrimidin-4-amine (PA-1) against Botrytis cinerea (B. cinerea), the three-dimensional structure of B. cinerea pyruvate dehydrogenase complex E1 component (PDHc-E1) is homology modeled, as the PA-1 shows potent E. coli PDHc-E1 and B. cinerea inhibition. Subsequent molecular docking indicates the PA-1 can tightly bind to B. cinerea PDHc-E1. Molecular dynamic simulation and MM-PBSA calculation both demonstrate that two intermolecular interactions, π-π stacking and hydrophobic forces, provide the most contributions to the binding of PA-1 and B. cinerea PDHc-E1. Furthermore, the halogen bonding interaction between the iodine atom in PA-1 and OH in Ser181 is also crucial. The present study provides a valuable attempt to homology model the structure of B. cinerea PDHc-E1 and some key factors for the rational structure optimization of PA-1.

Keywords: 5-iodo-1,2,3-triazole, Botrytis cinerea, PDHc-E1 inhibitor, homology modeling, molecular dynamic simulation; DOI: 10.14102/j.cnki.0254-5861.2011-3335

1 INTRODUCTION

Targeting the key enzyme that locates in the energy metabolic route is a major strategy to design novel bactericides or fungicides[1]. The pyruvate dehydrogenase multienzyme complex (PDHc), which connects the glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid cycle, a crucial step catalyzing the decarboxylation of pyruvate to form acetyl-CoA, is considered as a new target[2]. Among the complex, the E1 component of PDHc(PDHc-E1), which uses thiamin diphosphate (ThDP) as coenzyme, catalyzes the first vital reaction of the decarboxylation of pyruvate. Therefore, the PDHc-E1 inhibitors derived from ThDP analogs were synthesized and showed potent inhibition[3-5].

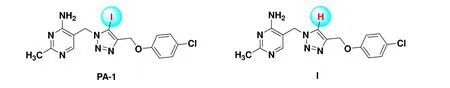

Previously, we have also been working on the design of novel ThDP analogs showing strong PDHc-E1 inhibition and their binding mechanism[6-10]. A series of 5-(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl-2-methylpyridin-4-amine derivatives were synthesized and showed moderate to potent inhibition against PDHc-E1 fromEscherichia coli(E. coli)[9]. Interestingly,compounds with and without iodine on the 5-position of 1,2,3-triazole ring showing distinct enzymatic inhibition and antifungal activities was found (Fig. 1), for example, the compound PA-1, 5-((4-((4-chlorophenoxy)methyl)-5-iodo-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl-2-methylpyrimidin-4-amine(Fig. 1), exhibited 98% growth inhibition against theBotrytis cinerea(B. cinerea) andRhizoctonia solani(R. solani) at 50μg/mL, much higher than compound I (Fig. 1) which was hydrogen atom instead of iodine atom, showing only 73%and 23% inhibition even at 100μg/mL[9]. TheEC50andEC90of PA-1 againstB. cinereawere 5.4 and 21.1μg/mL, respectively, which was around 5 times higher in effectiveness than the pyrimethanil, a commercial fungicide[9].

Fig. 1. Scheme of molecules of PA-1 and compound I

As we all know,B. cinereais a destructive plant pathogen that easily results the gray mold disease in more than 1000 plant species and serious economic loss[11]. Discovery of novel antifungal compounds againstB. cinereais an urgent and challenging work because of the high fungicide resistance due to its genetic plasticity under selective pressure[12]. To clarify the mechanism and guide the rational structure optimization of PA-1, we studied the difference of PA-1 and compound I (Fig. 1) by the combination of crystallography and density functional theory (DFT), demonstrating that the potential halogen bonding interaction took place in the iodine atom and residues with electron donor moieties, such as N, O and S, was the key driving force[13].However, it just primarily pointed out the different mechanisms between them. Therefore, an in-depth analysis of the protein-ligand interaction is still needed to promote the structure optimization.

Exploring the interaction between PA-1 andB. cinereaPDHc-E1 is by far not accessible since the purification process and crystal structure ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 are difficult and not reported. Under the circumstances, computer-aided modeling is an effective approach to theoretically get information between ligand and protein[14]. Homology modeling is the only alternative and proven method to get the threedimensional (3D) structure of the target protein in the absence of crystal structure[15], which can be used for further exploring the binding interaction between ligand and protein and as a guide to conduct further structure-based optimization.

The first objective of present work was intended to propose the 3Dstructure model ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 by homology modeling strategy, using the human PDHc-E1 as a template because of their high sequence identity. The second objective was to expound the binding mode theoretically between PA-1 andB. cinereaPDHc-E1 with the help of molecular docking and molecule dynamic simulation. To quantify the energetic nature of PA-1 binding, the molecular mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA)protocol was utilized to provide comprehensive information about their interaction.

2 EXPERIMENTAL

2. 1 Homology modeling

The protein sequence ofB. cinerea(Botryotinia fuckeliana) PDHc-E1 alpha and beta chain (Uniprot KB: M7UM99 and M7U6N2) were got from BLAST, and the template structure of human PDHc-E1 (PDB ID: 6CER)[16]was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) suite was used to build the homology model ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1[17]. The protonation state and the orientation of hydrogens in modeled protein structure were optimized by the LigX implemented in MOE at pH 7 and 300 K. First, after aligning the protein sequences ofB. cinereaand human PDHc-E1, ten independent intermediate models were built, by considering the permutational selection of different loop candidates and side-chain rotamers. Then, the GB/VI scoring function was chosen to score the intermediate models and pick out the final model, which was conducted to further energy minimization using the force field ofAMBER10:EHT.

2. 2 Molecular docking

Molecular docking was conducted in MOE suite to predict the binding modes and affinities of PA-1 and two PDHc-E1 fromB. cinereaandE. coli. The 3Dstructure of PA-1 was built by converting the 2Dstructure through energy minimization in MOE. The binding site is defined the same as the position of TDP in the human PDHc-E1 (PDB ID: 6CER).Before docking, the force field of AMBER10:EHT and the implicit solvation model of reaction field (R-field) were selected. The “induced fit” docking protocol was used, that is, the residue side chains in the receptor pocket, with a constraint on their positions, were allowed to move to fit the ligand conformations. The weight used for tying the sidechain atoms to their original positions was set as 10. All docked poses were first ordered by London dG scoring, then the top 30 docking poses were applied for force field refinement and followed by rescoring using the GBVI/WSA dG[18]. The final binding modes of PA-1 and PDHc-E1 was identified with best-ranked pose.

2. 3 Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

The best-ranked complex ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 with PA-1 after docking was used for further MD simulation. The force field parameters of PA-1 were chosen as MMFF94[19].Hydrogen atoms of PA-1 were optimized at the level of HF/6-31G* in Gaussian09 package[20], and then the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP)[21]charge was used to calculate the partial atomic charges. To neutralize and solvate the complex, sodium/chlorine counter ions and solvated in a cuboid box of TIP3P water molecules were added, with 10 Å of solvent layers between the box edges and solute surface.

All MD simulations were performed using AMBER16[22]by applying the AMBER GAFF and FF14SB force fields.The SHAKE algorithm was used to restrict all covalent bonds involving hydrogen atoms with a time step of 2 fs.The treatment of long-range electrostatic interactions was employed the method of Particle Mesh Ewald (PME)[23]. For solvated system, the heating step simulation was conducted after two steps of minimization. First, 4000 cycles of minimization were carried out with all heavy atoms fettered with 50 kcal/(mol·Å2), while the solvent molecules and hydrogen atoms can move freely. Then, the non-restrained minimization was performed in two steps, involving 2000 cycles of steepest descent minimization and conjugated gradient minimization, respectively. Subsequently, the whole system was heated from 0 to 300 K in 50 ps employing Langevin dynamics at a constant volume, followed by equilibrating for 400 ps at the 1 atm pressure. All the heavy atoms were restrained at the weak constraint of 10 kcal/(mol·Å2) throughout the heating steps. Periodic boundary dynamics simulations were performed for the whole system with constant composition, constant pressure (1 atm), and constant temperature (300 K) in the production step. 100 ns simulation was accomplished for the production phase. The calculation of binding free energies was employed the MM-PBSA method.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3. 1 Sequence analysis

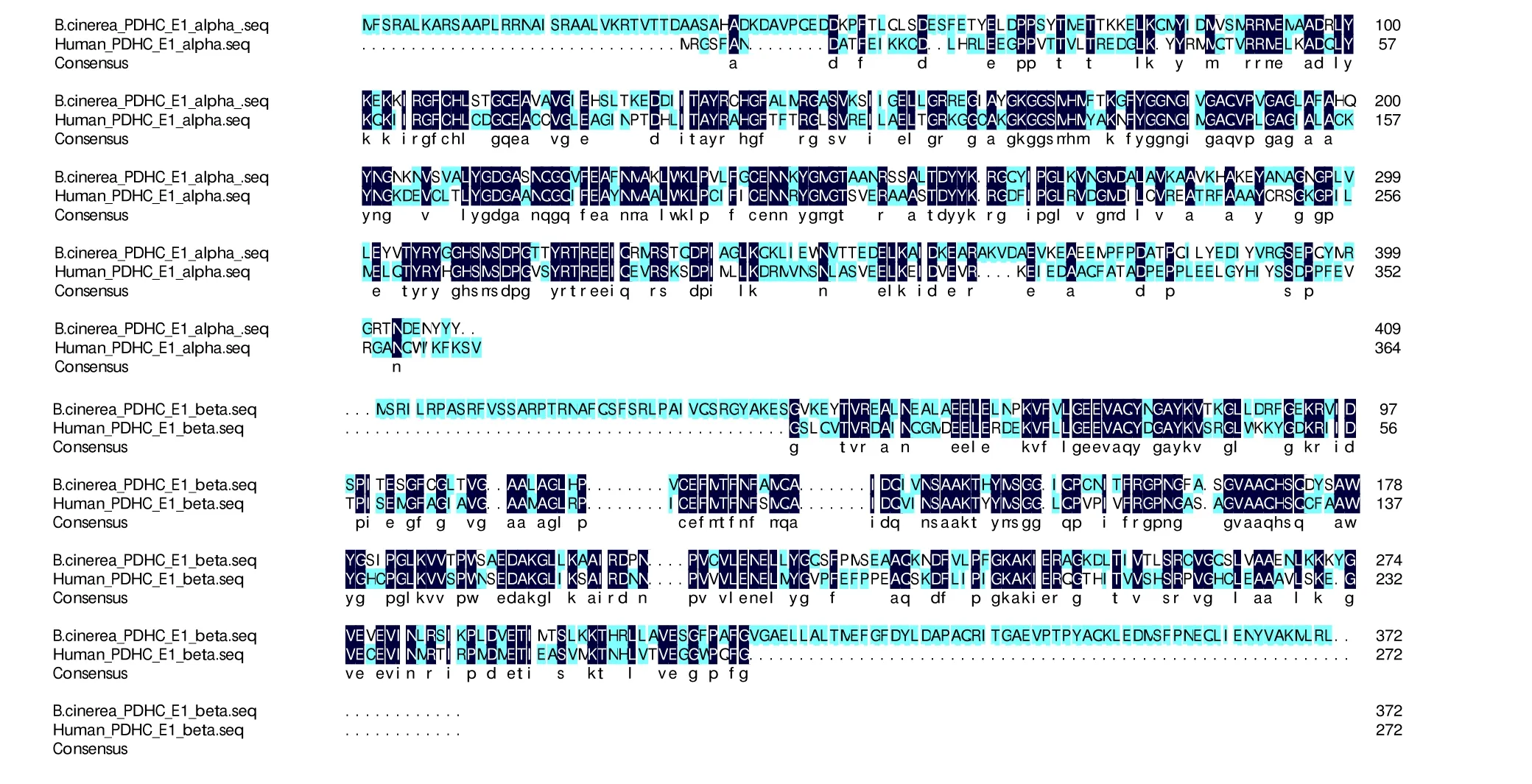

Fig. 2. Sequence alignment between B. cinerea PDHc-E1 and human PDHc-E1(PDB ID: 6CER) with the % of the identity of alpha and beta chain of 45.2% and 46.2%, respectively

The 3Dstructure ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 was built using homology modeling as it was not reported by either X-ray crystallography or NMR spectroscopy. The FASTA sequence of theB. cinereaPDHc-E1 with alpha and beta (Uniprot KB:M7UM99 and M7U6N2) was retrieved from the UniportKB server and the chain lengths are 409 and 372 amino acids,respectively. The PDB ID 6CER with a resolution of 2.69 Å was selected as template protein[16]because theB. cinereaPDHc-E1 and the template protein showed a high sequence identity of 45.2% and 46.2% for the responding alpha and beta chains, which are acceptable for 3Dmodel building.The pairwise sequence alignment of theB. cinereaPDHc-E1 and the template 6CER was performed using CLUSTALW-2,which is represented in Fig. 2.

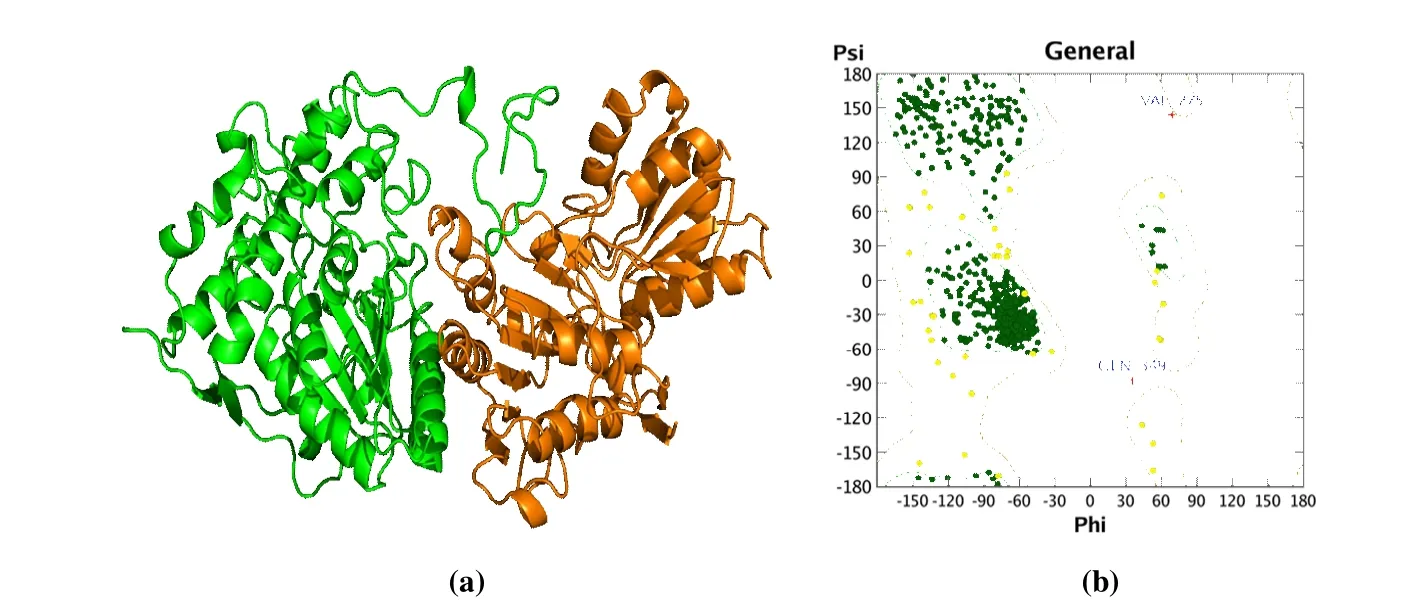

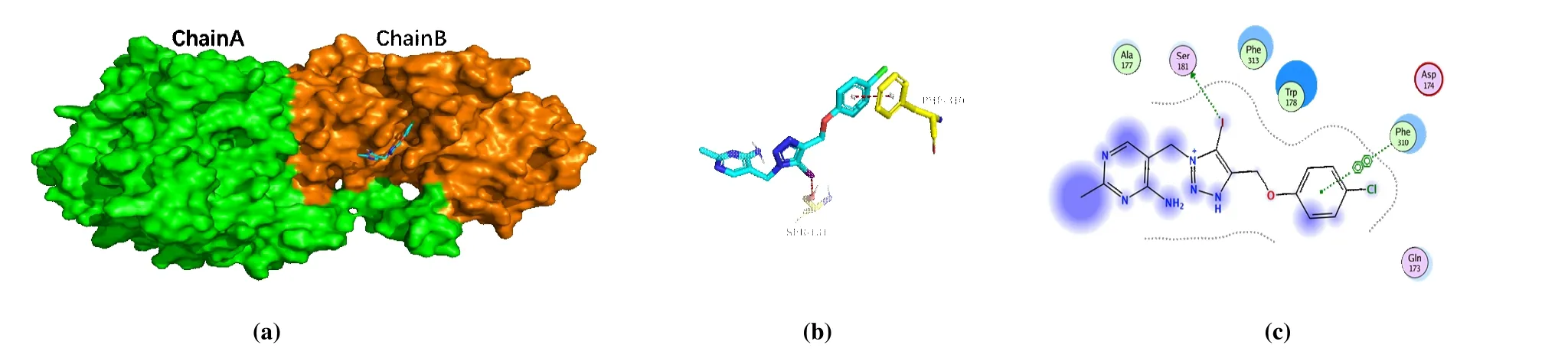

3. 2 Homology modeling of B. cinerea PDHc-E1

3Dmodel ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 was generated using the MOE program. Ten independent intermediate models built by aligning theB. cinereasequence to the human sequence were scored according to the GB/VI scoring function. The model with the highest score was considered as the final model and was conducted for further energy minimization employing the AMBER10:EHT force field. The 3Dmodeling structure ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 is depicted in Fig. 3a.The average root means square deviation (RMSD) value between the 3Dstructure ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 and 6CER was 1.408 Å, and the alpha- and beta-sheet regions displayed high similarity. The Ramachandran plot (Fig. 3b) forB.cinereaPDHc-E1 indicated the built 3Dstructure of the model is highly reasonable, since 99% of residues located in the allowed regions[24].

Fig. 3. (a) Homology model of B. cinerea PDHc-E1. The alpha chain of PDHc-E1 is shown as green cartoon, and the beta chain of PDHc-E1 is shown as orange cartoon. (b) Ramachandran plot for B. cinerea PDHc-E1. Dark green dots, yellow dots, and red cross represent the residues located in favored regions, allowed regions, and irrational regions, respectively

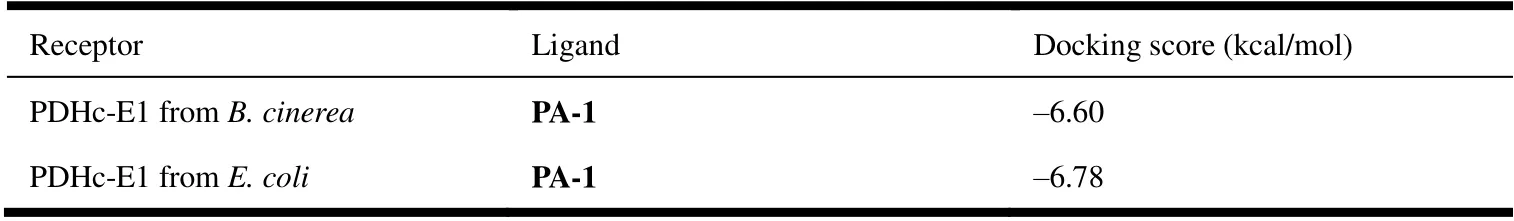

Table 1. Docking Scores of PA-1 with B. Cinerea and E. Coli PDHC-E1

3. 3 Molecular docking

To reveal the binding mode and affinity of PA-1 and PDHc-E1 fromB. cinereaandE. coli, respectively, molecular docking was performed. Docking scores shown in Table 1 indicated similar binding affinity of PA-1 with both different enzymes, which are -6.60 and -6.78 kcal/mol. Fig. 4a and 4d both showed that PA-1 bound on the surface cavity ofB. cinereaandE. coliPDHc-E1, while the moiety of PA-1 exposed out of the protein was different, which were pyrimidine ring plus 1,2,3-triazole ring and benzene ring, respectively, forB. cinereaandE. coli, as shown in Figs. 4b and 4e.The 3Dbinding mode in Fig. 4c displayed that the hydrogen bonding between N atom in pyrimidine ring and OH in Ser109, N-H-πinteraction between Asn260 and pyrimidine ring, andπ-πstacking between the residue His142 and 1,2,3-triazole ring all played major roles in the binding affinity.Besides, the benzene ring is in a hydrophobic hole formed by His106, Tyr177, Val192, and so on, indicating the hydrophobic interaction may be also an important factor. In contrast, only the direct hydrogen bonding interaction between Arg306 and N atom in 1,2,3-triazole ring was found for PA-1 inE. coliPDHc-E1 (Fig. 4e), but the pyrimidine and benzene rings both located in a hydrophobic cavity, which provided the steric matching and hydrophobic interaction.The obvious different binding modes of PA-1 in the binding sites ofB. cinereaandE. coliPDHc-E1 give us an important guidance to the modification of PA-1 and may explain its potential mechanism on the interaction with fungal and bacterial PDHc-E1.

Fig. 4. Molecular docking results of PA-1 with B. cinerea and E. coli PDHc-E1. (a) 3D binding mode of PA-1 with B. cinerea PDHc-E1; (b) 2D binding mode of PA-1 with B. cinerea PDHc-E1; (c) Optimal binding interaction of PA-1 with the active site residues of B. cinerea PDHc-E1;(d) 3D binding mode of PA-1 with E. coli PDHc-E1; (e) 2D binding mode of PA-1 with E. coli PDHc-E1; (f) Optimal binding interaction of PA-1 with the active site residues of E. coli PDHc-E1. The blue dots in b and e mean ligand exposure

3. 3 Molecular dynamic simulation

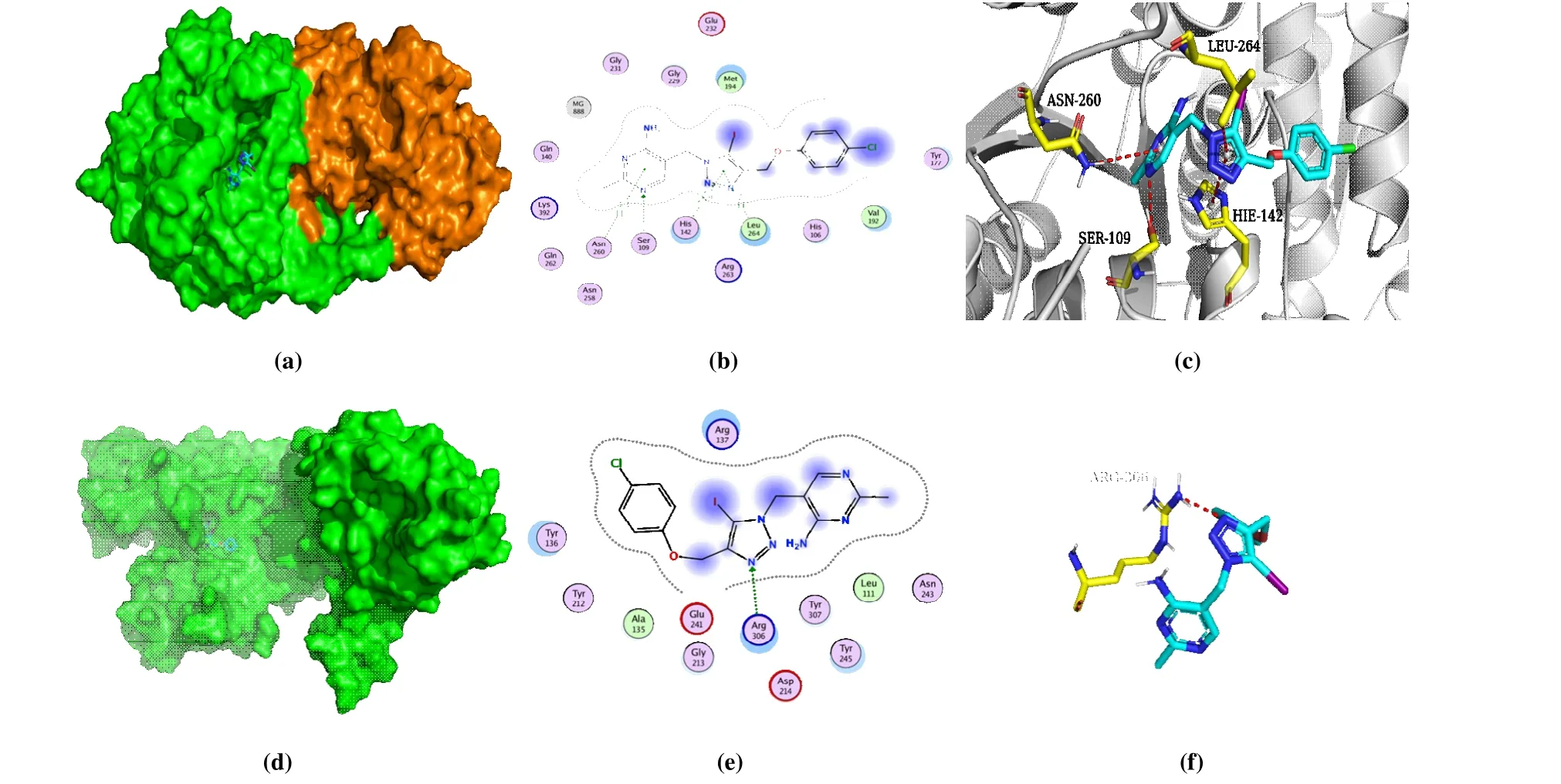

The best-ranked complex ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 with PA-1 after docking was optimized by all-atom, explicitwater MD simulations. It can be seen from the Fig. 5 that the RMSD of the backbone of PDHc-E1 and PA-1 was less than 4.0 and 3.0 Å, respectively, and all the system achieved equilibrium within the simulation time, suggesting the adequation of force field and simulation protocol. Clustering strategy was applied to the MD trajectory to analyze the complex, and the cluster center was selected as the final stable complex ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 and PA-1, which is shown in Fig. 6.

The binding site of PA-1 inB. cinereaPDHc-E1 changed toβ-subunit after MD simulation (Fig. 6a), and the binding mode significantly changed with the benzene ring rearranged in a hydrophobic cavity formed by some greasy residues(Trp178, Phe310, and 313), along with theπ-πstacking interaction with Phe310 (Figs. 6b and 6c). The intermolecular interaction between pyrimidine and 1,2,3-triazole ring with residues became less, but it is worth noting that a new bonding formed between iodine atom and OH in Ser181 after MD simulation. As previously reported[13], the interaction was halogen bonding, an electrostatic interaction between electropositive region of iodine atom and the electron donor moiety of oxygen atom. The newly formed halogen bonding provides new insight on the binding mode of PA-1 andB.cinereaPDHc-E1, and the finding follows our previous report[13]shows that the halogen bonding between iodine atom with residue in active site provided a key effect on the enhancing of antifungal activity. The binding modes after molecular docking and MD simulation provide a deep cognition to rationalize the structure optimization of PA-1 asB. cinereaPDHc-E1 inhibitors, that the iodine atom retaining is indispensable.

Fig. 5. System flexibility analysis of complexB. cinerea PDHc-E1 with PA-1

Fig. 6. Complex of PDHc-E1 with PA-1. (a) Binding model of PA-1, colored in cyan, on the molecular surface of B. cinerea PDHc-E1. (b) Intermolecular interaction of PA-1 with the binding site residues of B. cinerea PDHc-E1. (c) 2D binding mode of PA-1 with B. cinerea PDHc-E1.The yellow-colored residues in c represent the surrounding residues in the binding pockets. The blue dots in c mean the ligand exposure

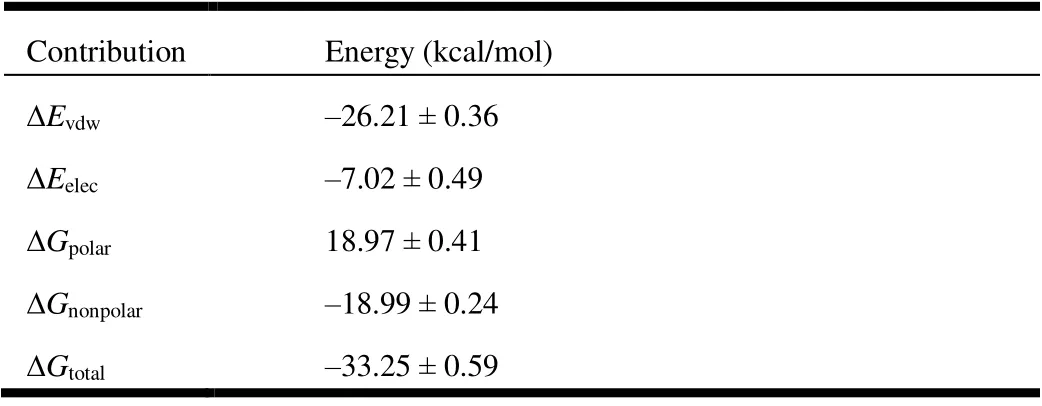

Table 2. Average Binding Energy and Its Components Obtained from the MM-PBSA Calculation for the B. Cinerea PDHc-E1 and PA-1 Complex

The binding free energy (ΔGtotal) ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1 with PA-1 calculated by utilizing the MM-PBSA method[25]is shown in Table 2. The Van der Waals (VdW) and electrostatic interactions contributed to ΔGtotalwere expressed as ΔEvdwand ΔEelec. The ΔGpolarand ΔGnonpolarrepresent the polar and nonpolar solvation energy contributions to ΔGtotal,respectively. The binding energy of -26.21 kcal/mol for ΔEvdwindicates that the PDHc-E1 and PA-1 binding is largely influenced by the VdW interaction, indicating that ΔEvdwis the most favorable contributor. Meanwhile, the negative ΔGnonpolar(-18.99 kcal/mol) and positive ΔGpolar(18.97 kcal/mol) indicate nonpolar interaction is favorable for the binding, but not for polar interaction. The electrostatic interaction (ΔEelec= -7.02 kcal/mol) also provides a little contribution to the binding. At last, the final binding free energy, ΔGtotal, uponB. cinereaPDHc-E1 with PA-1 was calculated to be -33.25 kcal/mol in aqueous environments.

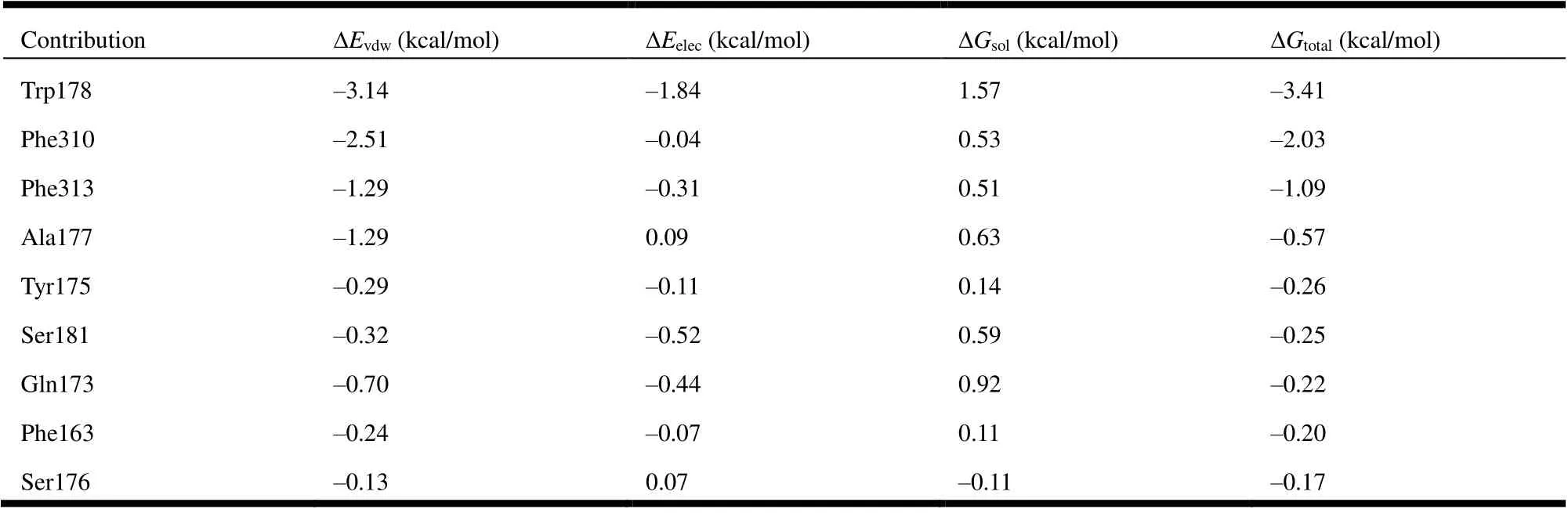

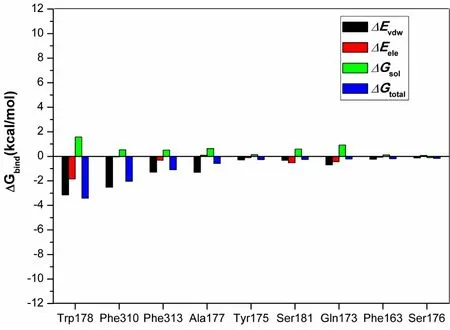

Table 3. Energy Decomposition of the Ranked Top 9 Residues

Further energy composition analysis suggests that the residues Trp178, Phe310, Phe 313, and Ala177 provided most contribution to the complex binding free energy (Fig. 7 and Table 3). Trp and Phe are aromatic residues that can formπ-πstacking and hydrophobic forces; the most contribution of these residues indicates further structural optimization of PA-1 needs to pay more attention to the potential interaction with these residues. It is worth noting that the ΔEelecbetween PA-1 and Ser181 was -0.52 kcal/mol, which was the second only to Trp178, indicating the reservation of iodine is also important to enhance the biological activity.

Fig. 7. Energy decomposition. The contributions of ranked top 9 residues on the binding free energy

4 CONCLUSION

As far as we know, we first reported the reliable homology model ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1. The ongoing theoretical study about the binding mode and binding free energy of PA-1 withB. cinereaPDHc-E1 was performed based on molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation, as well as compared to the results of PA-1 withE. coliPDHc-E1. Results showed PA-1 had a significant difference in binding betweenB. cinereaandE. coliPDHc-E1 by molecular docking, which might be due to the low homology.After MD simulation, the binding site of PA-1 migrated toβ-subunit ofB. cinerea, and an obvious new intermolecular bonding, halogen bonding between iodine atom and OH in Ser181, formed. Binding free energy calculated by the MM-PBSA method indicated theπ-πstacking and hydrophobic forces provided the most contribution to the binding of PA-1 andB. cinereaPDHc-E1. Meanwhile, the second electrostatic interaction was also noticeable. The present study not only provided the first report of homology modeling ofB. cinereaPDHc-E1, but also provided key information to understand the potential interactions of PA-1 andB. cinereaPDHc-E1 that can be used for rational structure optimization.

- 结构化学的其它文章

- Structural and Electronic Properties of Lutetium Doped Germanium Clusters LuGen(+/0/-) (n = 6~19):A Density Functional Theory Investigation①

- Discovery of Benzimidazole Derivatives as Novel Aldosterone Synthase Inhibitors: QSAR, Docking Studies, and Molecular Dynamics Simulation①

- QSAR Models for Predicting Additive and Synergistic Toxicities of Binary Pesticide Mixtures on Scenedesmus Obliquus①

- Preparation, Crystal Structure and Fungicidal Activity of N-(5-(benzofuranol-7-oxymethyl)-1,3,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)amide Compounds①

- Antibiotic Silver Particles Coated Graphene Oxide/polyurethane Nanocomposites Foams and Its Mechanical Properties①

- Planar Tetracoordinate Carbon in 6σ + 2π Double Aromatic CBe42- Derivatives①