Successful treatment of an enormous rectal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma by endoscopic full-thickness resection: A case report

Fang-Yuan Li, Xiao-Long Zhang,Qi-De Zhang, Yao-Hui Wang

Abstract

Key Words: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; Endoscopic full-thickness resection; Endoscopic minimally invasive surgery; Endoscopy; Case report

lNTRODUCTlON

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma) is a subtype of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma derived from B cells in the peripheral follicular area of lymph nodes. As MALToma progresses, it may transform into diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which has high malignancy. Despite the increase in detection rate, colorectal MALToma, accounting for only 2 .5 % of gastrointestinal MALTomas, is still a rare disease worldwide[1 ]. As a result, the clinical characteristics, especially the endoscopic features,and standard therapy of colorectal MALToma have not been clearly established. In this case report, we describe a large rectal MALToma that was treated successfully with endoscopic full-thickness resection(EFTR), which may provide a new solution for colorectal MALToma.

CASE PRESENTATlON

Chief complaints

A 71 -year-old woman visited our institution to address intermittent hematochezia.

History of present illness

The patient’s symptoms started 1 mo prior, accompanied with abdominal pains but without weight loss,fever, chills or fatigue.

History of past illness

The patient had a free previous medical history.

Physical examination

No other obvious sign was detected, except by digital rectal examination, which revealed a large protrusive lesion but left no blood on the gloves.

Laboratory examinations

No positive findings were obtained from the standard laboratory tests (including blood routine and markers of liver function, renal function and tumor).

Imaging examinations

Figure 1 Endoscopic features of the lesion. A: White light endoscopy discovered a huge volume of subepithelial tumor in the lower rectum; B: Uneven and hyperemic coverage of mucosa; C: Narrow-band imaging magnifying endoscopy showing the irregular branching vascular (arrow); D: Disappeared glandular structure(arrow), which is called tree-like appearance.

Colonoscopy showed a 60 mm × 50 mm hemispheric mass in the lower rectum at 20 mm proximal to the anal verge, showing rough and hyperemic mucosa (Figure 1 A and B). The narrow-band imaging magnifying (NBI-M) endoscopy detected some branching abnormal blood vessels and disappearance of glandular structure. This specific manifestation was consistent with the tree-like appearance (TLA) sign as is described in gastric MALToma (Figure 1 C and D). Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) revealed the lesion to be hypoechoic, boundary-defined, and echo uniform inside, originating from the muscularis propria (Figure 2 A). Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) also demonstrated a 50 mm × 30 mm soft tissue mass with defined boundary in the lower rectum (Figure 2 B). No enlarged superficial lymph nodes were detected by B-mode ultrasound. Additionally, C13 -urea breath test and serumHelicobacter pyloriantibody were both negative.

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

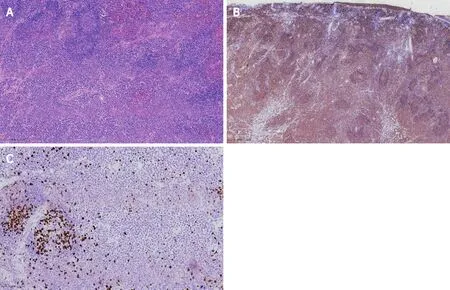

Histopathological analysis revealed lymphoid proliferation with dysplasia, accompanied by variable large cells. The tumor cells were positive for CD20 , Pax-5 and mum-1 , and negative for CD3 , CD5 ,CD10 , c-myc, SOX11 and cyclin-D1 . The Ki67 index was 5 %. Light-chain restriction determination showed kappa restriction. Taken together, the final diagnosis of the presented case was compatible with MALToma (Figure 3 ).

TREATMENT

Considering the location and volume of the lesion, surgical operation would not be able to preserve the anal structures. Therefore, after sufficient communication with the patient, we performed EFTR under intravenous anesthesia (Video). During the operation, a special T-type endoknife (ESD knife; Micro-Tech, Nanjing, China) was used to cut through the mucosal surface into the submucosa layer by layer and the tumor body was exposed clearly. Then, we further stripped the connective tissue until the tumor was completely removed (Figure 4 A). Finally, 14 SureClipsTM(SureClipTMHemoclips; Micro-Tech)combined with an endoloop were used for purse suture of the wound (Figure 4 B and C). The tumor

Figure 3 Histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of the specimen. A: Hematoxylin-eosin staining, × 100 ; B: CD20 staining, × 40 ; C:Ki67 , × 200 .

tissue with intact capsule was removed by a nylon rope and the measured size was about 65 mm × 55 mm (Figure 4 D). Preventive antibiotic was prescribed for 3 d after the operation.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient recovered steadily and was discharged 5 d after our endoscopic surgery. Six months later,positron emission tomography-CT examination showed no sign of residual lesions or lymph node metastasis. Follow-up colonoscopy after 12 mo revealed a healed lesion without remnants.

DlSCUSSlON

Given that colorectal MALToma only accounts for a small proportion of all colorectal malignancies, its clinical features are largely unknown[1 ,2 ]. The population most susceptible to colorectal MALToma are middle-age and old-age women, and a few of the patients may exhibit some latent symptoms, such as fecal occult blood and black stool[2 ,3 ]. Colonoscopy remains an effective diagnostic method for MALToma. However, there is still no consensus on the relevant endoscopic characteristics and classification of colorectal MALTomas[2 ]. Recent studies have suggested some characteristics of colorectal MALToma. For example, the most common site is the rectum and the lesion usually appears as a singlet[1 ,2 ]. In addition, the most common endoscopic phenotype is subepithelial tumor (commonly referred to as SET) type, followed by polyposis type, ileitis type, and epithelioid mass type[2 ]. All these characteristics were in accordance with that in our case. However, in contrast to that in the present case, tumors >50 mm in size, mostly within 20 mm according to a previous report[1 ], have been seldom reported.Conventionally, submucosal tumor with low echo lesion feature as evaluated by EUS has been most often considered as gastrointestinal stromal tumor, lipomyoma or neuroendocrine tumor. In the present case, the uneven and broken surface detected in white light mode caught our attention. We decided to perform NBI-M endoscopy to observe this lesion and delineate the border. A TLA, similar to the description of gastric MALToma in some reviews[4 ], was obvious (Figure 2 ). We reviewed the lesion pictures and descriptions in some previous reports and we recognized that all these statements were indicating the same endoscopic characteristics[5 ,6 ]. This finding suggested that the TLA sign may also be a specific feature of colorectal MALToma.

Today, the standard therapy of colorectal MALToma is still under debate. Different from gastric MALToma, colorectal MALToma showed no significant association withH. pyloriinfection and no satisfactory response toH. pylorieradication in most cases[7 ,8 ]. Although some experts still considerH.pylorieradication as the first-line treatment because of noninvasiveness[9 ], anti-H. pyloritherapy seems unnecessary and unreasonable for those patients who test negative forH. pylori; this was similar to the situation in the present case. From another perspective, colorectal MALTomas have their own features.Many clinical retrospective studies have indicated that most colorectal MALTomas could be classified as Lugano stage I and II, which are considered of lower malignancy and more slowly progressive[3 ,10 ].Meanwhile, it has been indicated that the long-range outcome exhibits no significant difference between the patients who received monotherapy and those who received combined therapy (surgery or radiation)[2 ]. These features offer the possibility of locoregional treatments, such as endoscopic resection, surgical resection, and radiotherapy[11 ]. Therefore, endoscopic resection, as a mini-invasive therapy, seems to be an appropriate therapeutic option for early-stage colorectal MALTomas.

Interestingly, we noticed that nearly half of the cases treated by conventional endoscopic techniques tested positive on surgical margins, due to the diversity of endoscopic morphology and the lesion size[2 ]. In the present case, allowing for the large size of this lesion and the patient’s strong desire for anal preservation, EFTR seemed to be a good treatment strategy. This allowed us to resect a deep tumor with a small piece of the complete gastrointestinal wall without any assisted device[12 ]. During this operation, the highest priority is the complete removal of the tumor without interruption of its capsule.Meanwhile, the skillful use of the endoknife helped reduce the switch between instruments and improved efficiency. The purse suture, consisting of SureClipsTMand endoloop, can decrease the tension on the wound and reduce the occurrence of delayed perforation. Although some reports have indicated that over-the-scope clips have good overall technical efficacy in stitching wounds of lesions ≤ 2 cm[12 ],the purse suture has the potential to be a cost-effective approach for giant lesions.

CONCLUSlON

Colorectal MALToma, which lacks clinical and endoscopic features, is easily missed and misdiagnosed.Prior to histological diagnosis, a predictable identification of suspicious lesion under endoscopy is important to define the border of the lesion and prevent margin-positive resection. Meanwhile, accurate pathological diagnosis is also challenging, and endoscopists and pathologists must renew the research progress on this rare disease in time and join efforts for improving rates of final diagnosis. According to our successful experience with the present case, EFTR combined with purse suture seems to be a feasible and economical choice for the treatment of enormous colorectal MALToma, especially of the SET type. However, the combined application of EFTR and another therapy scheme needs further clinical practice.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Zhang QD conceived and performed the operation; Wang YH analyzed and interpreted the histopathological and immunohistochemical results; Li FY collected the clinical information and wrote the manuscript; Zhang XL revised the manuscript.

Supported byNational Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82004298 .

lnformed consent statement:Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016 ) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016 ), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016 ).

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORClD number:Fang-Yuan Li 0000 -0003 -4802 -4514 ; Xiao-Long Zhang 0000 -0003 -2803 -6366 ; Qi-De Zhang 0000 -0002 -9222 -6036 ; Yao-Hui Wang 0000 -0001 -6001 -9457 .

S-Editor:Fan JR

L-Editor:Kerr C

P-Editor:Fan JR

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年10期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年10期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Comment “Asymptomatic small intestinal ulcerative lesions: Obesity and Helicobacter pylori are likely to be risk factors”

- Gut dysbiosis and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth as independent forms of gut microbiota disorders in cirrhosis

- Diagnostic performance of endoscopic classifications for neoplastic lesions in patients with ulcerative colitis: A retrospective case-control study

- Loss of LAT1 sex-dependently delays recovery after caerulein-induced acute pancreatitis

- Malignant biliary obstruction due to metastatic non-hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer

- Feasibility of therapeutic endoscopic ultrasound in the bridge-to-surgery scenario: The example of pancreatic adenocarcinoma