口服避孕药对女运动员前交叉韧带损伤风险影响的认识进展

杨 璐,徐 妍,2

口服避孕药对女运动员前交叉韧带损伤风险影响的认识进展

杨 璐1,徐 妍1,2

1.南京体育学院,江苏 南京,210014;2.南京市再生医学工程技术研究中心,江苏 南京,210046。

前交叉韧带(Anterior Cruciate Ligament,ACL)损伤在运动人群中非常常见,随着国内竞技体育的发展和群众体育的普及,ACL损伤的发生率明显升高;并且由于激素的影响,在各种运动中,女运动员ACL损伤的发生率明显高于男运动员。ACL损伤带来短期及长期的不良影响,包括重建手术、长期康复治疗和后期患骨关节炎风险增大等,对社会来说也是一个巨大的财政负担。鉴于ACL损伤对个人及社会的不利影响,预防ACL损伤至关重要。本综述复习了激素对于女运动员ACL损伤的影响机制,在此基础上探讨口服避孕药(Oral Contraceptive,OC)对ACL损伤风险的影响以及今后的研究方向。

前交叉韧带;口服避孕药;激素;基质金属蛋白酶;损伤风险;认知进展

ACL是膝关节内重要的韧带之一,是控制膝盖前后向稳定和旋转稳定的重要结构,一旦断裂,将严重影响膝关节的稳定性和运动功能,进而导致关节软骨和半月板的继发损伤。ACL损伤在运动人群中非常常见,流行病学研究发现,在各种运动中,女运动员前交叉韧带损伤的发生率是男运动员的2到9倍,有研究认为这是一种激素效应。雌激素和松弛素均已显示出通过降低ACL胶原蛋白表达和增加基质金属蛋白酶的表达而对ACL产生分解代谢作用,而孕酮已被证明具有拮抗作用并促进胶原蛋白含量的增加。激素避孕药被认为通过改变雌激素、孕酮和松弛素的循环水平来影响ACL的完整性。本文将简要探讨口服避孕药影响ACL损伤风险的作用机制并分享相关进展。

1 ACL损伤在女性中高发

ACL损伤是一种非常常见的运动损伤,涉及着陆、减速和方向改变,会带来短期及长期的不良影响,包括重建手术、长期康复治疗和后期患骨关节炎风险增大等;对运动员而言,ACL损伤可能导致无法参加体育赛事、甚至长期残疾以及体育生涯的终结。在一项对足球运动员的研究中,即使ACL被修复,再损伤的风险也会增加,同时损伤肢体的感觉系统运动控制、协调和姿势也会出现缺陷[1,2]。研究表明,女性ACL损伤的发生率是男性的2至9倍[3],特别是在足球、篮球、排球和体操等运动项目中,女性的受伤率要高得多[4]。例如,在篮球运动中,女性ACL损伤的概率是男性的3倍[5];在基础军事训练的横渡障碍课程时,女性ACL损伤概率比男性多11倍[6]。

造成这种差异的原因可能是解剖和生物力学因素,包括肌肉激活模式不同[7]。同时,越来越多的研究表明,女性的性激素也可能是影响ACL损伤发生率的重要因素,并且由于激素相对易于控制,在ACL损伤前的预防和损伤后的治疗上都具有实际的应用意义[8-11]。

2 月经周期与 ACL损伤

男性和女性的一个显著差异是女性的月经周期,在月经周期的不同阶段,女性ACL损伤的发生率不同。Arendt等[5]对38名女大学生运动员进行了研究,相较于月经周期中期,月经来潮之前或之后ACL受伤的风险更高。Myklebust等[12]回顾了挪威手球精英队女队员ACL损伤的情况,17名具有正常月经周期的运动员的回顾结果表明,在月经期开始之前或之后的一周内,ACL受伤的风险增加。此外,Ruedl[13]的研究表明,在月经周期的排卵前阶段,女性休闲滑雪者发生ACL损伤的可能性更大。

女性ACL损伤的发生率在月经周期的排卵期增加,此时雌激素水平激增,女性ACL损伤可能与激素波动有关,再由月经周期与激素水平之间相关性可以推断出激素水平与ACL损伤之间的关系。

2.1 月经周期及激素水平波动

月经周期根据卵巢及子宫的形态和功能分为三个阶段:卵泡期、黄体期和月经期。卵泡期又称增生期,一般为月经周期的第1-14天,与周期性募集的卵泡快速生长时期相对应。黄体期又称分泌期,一般为月经周期的第15-28天,该时期的时间长度相对稳定,而卵泡期的长短变化较大。月经期是月经周期开始的几天,与卵泡期的早期有所重叠,一般持续3-5天。

月经周期是下丘脑、垂体和卵巢三者相互作用的结果。在该周期不同阶段,下丘脑-垂体-卵巢轴的功能活动不同,导致雌激素、孕激素在第28天的平均周期内发生变化[14,15]。在正常的月经周期中,雌激素在第10天上升,在第12天达到峰值。孕激素在第15天上升,在第21天达到峰值。松弛素在第12天上升,并在第14天达到峰值[16,17]。

2.2 激素水平与ACL损伤发生率的关系

ACL主要由胶原组织组成,韧带的结构完整性高度依赖于胶原含量。I型胶原是ACL的主要原纤维类型,负责韧带的强度,保证结构完整性,Ⅲ型胶原蛋白则负责韧带的弹性[19]。基质金属蛋白酶-1(Matrix metalloproteinase-1,MMP-1)主要负责I型胶原蛋白的降解,并在Ⅲ型胶原蛋白的代谢中起一定作用。值得注意的是,III型胶原主要在损伤后的ACL修复过程中表达,因此与I型胶原蛋白相比,III型胶原蛋白对ACL的结构完整性起的作用可能要小得多[20]。研究证实,人、兔、大鼠的ACL上均存在雌激素、孕激素和松弛素受体[11,21-23],女性的性激素水平会影响胶原蛋白与MMP1表达之间的这种平衡,从而影响ACL的组成以及ACL的强度[24],影响ACL损伤的发生率。

2.2.1 雌激素和孕激素 此前的研究推测,雌激素通过刺激韧带对松弛素的敏感性降低胶原纤维的密度和组织,增加韧带松弛,并可能对ACL的承载性能产生影响[25]。在雌激素水平升高的情况下,胶原的合成减少,雌激素对肌腱基质组成有影响[11]。雌激素可降低软组织胶原含量,降低ACL拉伸强度[11,26,27]。当雌激素水平较高时,女性在月经周期的卵泡和排卵期发生更多的ACL损伤[28]。也就是说,雌激素水平的波动可能导致ACL成纤维细胞代谢的改变,这可能导致ACL的结构和组成变化,从而导致女性ACL的脆弱性增加[28,29]。Neugarten等[30]的研究还显示了雌激素对I型和IV型胶原蛋白产生的抑制作用。Liu[11]等的研究表明,雌激素通过降低胶原蛋白表达和增加MMP表达而对ACL产生分解代谢作用,而孕激素已被证明具有拮抗作用并促进胶原蛋白含量的增加。因此,雌激素水平在月经周期中的波动会对ACL中胶原的代谢产生负面影响,从而导致女性ACL损伤风险增加。

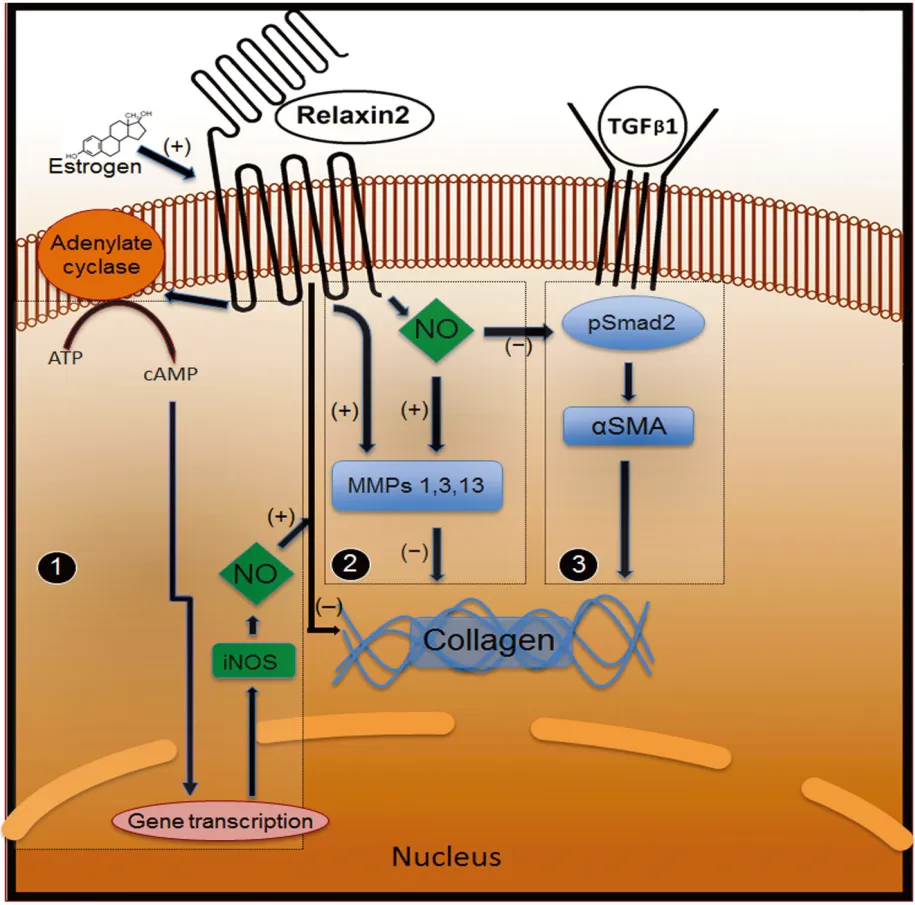

2.2.2 松弛素 松弛素通过降低胶原蛋白表达和增加MMP表达而对ACL产生分解代谢作用[11],在女性运动员中显著影响ACL损伤的发生率。松弛素在许多动物中的主要功能是通过刺激MMP的表达来放松耻骨联合,为分娩做准备,从而放大胶原蛋白的降解[16]。

美国大学体育协会(NCAA)的研究表明,血清松弛素浓度超过6.0pg/mL的女运动员ACL撕裂的可能性约为未达到此阈值的同龄人的4倍。当用雌激素灌注细胞并用松弛素处理细胞时,7位女性供体的ACL样品也显示出MMP表达增加和胶原蛋白表达降低。松弛素对雄性供体的ACL样品无影响[9],与男性ACL缺乏松弛素受体的观察结果一致[10]。

值得注意的是,松弛素对胶原组织的影响已被证明可与雌激素或孕激素并用而改变:雌激素可增强松弛素的胶原分解能力,而孕酮可减轻松弛素的作用[16]。此外,在联合使用雌激素和孕酮治疗后,大鼠膝关节韧带中的松弛素受体表达增加[31]。

图2 松弛素信号通路[9]

另外,除了可能对ACL或其对损伤的反应能力有直接影响外,激素还可能通过影响神经肌肉系统进而影响ACL的损伤。Zimmerman和Parlee[32]、Posthuma[12]等的研究都表明,在月经周期的不同阶段,女运动员的神经肌肉控制程度不同。Sarwar等[33]发现在排卵过程中骨骼肌功能会发生显着变化。而收缩和放松股四头肌的能力的改变,表明了排卵过程中膝关节保护性肌肉的刚度发生了显着变化,雌激素还通过对肌膜的保护作用来影响骨骼肌功能[34]。

3 口服避孕药与ACL损伤

近年来,使用口服避孕药(Oral Contraceptive,OC)的女性人数不断增加。在美国,15岁至44岁的女性中,有82%的女性使用OC;其中14%的女性使用OC并不是为了避孕,而是为了调节月经周期、治疗痛经或闭经等[35]。

3.1 OC的概况

OC可以既包含雌激素又包含孕激素,也可以仅包含孕激素;不同OC的剂量不同,有低剂量、中剂量或高剂量制剂。大部分OC由雌激素和孕激素联合合成类固醇组成,在抑制垂体促卵泡激素和黄体生成素产生和防止排卵方面起着重要作用[35]。早期的OC会阻止卵泡生长、排卵和黄体生成。卵巢类固醇水平较低的新型OC可使卵泡生长,但通常不会发生排卵[36]。OC能抑制下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴,通过抑制月经高峰期的雌激素和孕激素来抑制女性性激素的自然循环波动。然后,它抑制了排卵并阻止了黄体的形成,而黄体是松弛素的主要来源[31]。

3.2 OC与ACL损伤发生率的关系

关于口服避孕药的使用是否可以预防女运动员ACL损伤,不同的研究得出了不同的结论。较多的研究认为,使用OC通过调节月经周期内激素水平的波动降低了ACL损伤的发生率;也有部分研究认为,是否使用OC对ACL损伤的发生率无影响。

3.2.1 OC可以降低ACL损伤发生率 OC被认为通过改变雌激素、孕酮和松弛素的循环水平来影响ACL的完整性[37]。Nielson等[38]首先提出了OC与运动损伤之间可能存在联系,在该研究中,使用OC的女足球运动员比未使用OC的女足球运动员受伤少。Liu等[11]则首次通过鉴定来自13名女性和4名男性的ACL标本中的雌激素受体来证明人ACL是雌激素的靶组织,并通过体外研究推测OC可能对ACL有影响。Nielsen等对108名瑞典足球联赛的女足球运动员进行了为期12个月的跟踪研究,记录了所有创伤性损伤,并要求女运动员们填写了关于月经周期史、避孕药使用和月经紊乱的问卷。研究结果显示,OC使用组的创伤性损伤发生率低于非OC使用组,特别是膝盖和脚踝的损伤发生率。Martineau等[39]的研究显示,非OC使用的患者的前膝松弛程度高于OC使用者,因此得出结论:OC的使用减少了膝盖松弛。因此,OC可以减少ACL损伤的一种方法是降低松弛素水平,防止其分解作用[24]。一项对13 355名女性进行的药物流行病学研究表明,OC的使用与维持手术治疗ACL损伤的可能性之间存在保护性联系[40]。Gray等[7]的研究表明,在15-19岁年龄段,使用OC的女性的ACL重建率比未使用OC的女性低18%。

3.2.2 OC对ACL损伤的发生率无影响 Ruedl等[13]的一项病例对照研究结果显示,使用OC和不使用OC的女性休闲滑雪者的ACL损伤发生率没有差异。该研究认为:对于女性休闲滑雪者,使用OC和ACL损伤率无关。Lobato等[41]对女性下楼梯进行了步态分析,发现OC的使用对其无影响,因此认为,使用OC是否可以降低ACL的损伤率仍然值得怀疑。

造成不同结论的原因可能有两个:(1)是雌激素、孕激素及松弛素之间的相互作用,以及内源性雌激素和孕激素水平受身体和情绪因素的影响,这使整个情况变得更加复杂,ACL及其他软组织结构以及中枢神经系统处于非常复杂的刺激和生物反馈状态;(2)是使用的OC配方不同。不同配方的OC中雌激素和孕激素的含量不同,而雌激素和孕激素对ACL的作用是相对的,这可能是导致如上不同结论的最重要的因素。

3.2.3 不同配方OC与ACL损伤发生率的关系 此前很少有研究对不同配方的OC与ACL损伤的关系进行研究,2020年,Konopka等[24]评估了孕激素与雌激素比例不同的OC对大鼠ACL生物化学和生物力学特性的影响,结果显示孕激素与雌激素的比值更高的制剂导致ACL强度增加、I型胶原表达增加和MMP1表达减少,即孕激素与雌激素比值较高的OC制剂对ACL更有保护作用。

首先,雌激素和孕激素分别对ACL组织具有直接的分解代谢和合成代谢作用。因此,含更多孕激素和更少雌激素的OC使得I型胶原蛋白表达增加、MMP1表达减少和ACL强度增加[24]。其次,ACL主要表达的松弛素受体是松弛素/胰岛素样肽受体1(Recombinant Relaxin/Insulin Like Family Peptide Receptor 1,RXFP1)[42],雌激素可以通过上调RXFP1来增强ACL对松弛素的反应[9,31]。同时,由于松弛素主要是由黄体生成,而OC通过抑制下丘脑-垂体-性腺轴抑制了黄体的形成,所以OC降低了松弛素水平。松弛素会降低ACL组织中的I型胶原蛋白并增加MMP1表达,降低ACL强度。这些结果表明,雌激素少、孕激素多的OC配方可以通过增加ACL强度来更好地保护ACL免受伤害。

4 结 语

ACL损伤的发生机制十分复杂,越来越多的研究证实,激素发挥着重要的作用。研究激素与ACL损伤的关系,分析OC对激素水平的影响,探讨不同剂量OC干预方案的选择,可以帮助临床医生针对女运动员制订预防ACL损伤的方案,降低训练和比赛中的ACL损伤发生率,使女运动员受益。运动损伤管理应更多地关注损伤的预防以及识别损伤因素,降低损伤发生率,帮助运动员提高运动水平和延长职业生涯。

[1] J Yamazaki, T Muneta, Yj Ju, et al. The kinematic analysis of female subjects after double-bundle anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction during single-leg squatting[J]. Journal of orthopaedic science: official journal of the Japanese Orthopaedic Association, 2013, 18(02): 284~289.

[2] B Dingenen, B Malfait, S Nijs, et al. Postural Stability During Single-Leg Stance: A Preliminary Evaluation of Noncontact Lower Extremity Injury Risk[J]. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy, 2016, 46(08): 650~657.

[3] Sj Shultz, Se Kirk, Ml Johnson, et al. Relationship between sex hormones and anterior knee laxity across the menstrual cycle[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2004, 36(07): 1165~1174.

[4] Sb Mountcastle, M Posner, Jf Kragh, et al. Gender differences in anterior cruciate ligament injury vary with activity: epidemiology of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in a young, athletic population[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 2007, 35(10): 1635~1642.

[5] Ea Arendt, J Agel, R Dick. Anterior cruciate ligament injury patterns among collegiate men and women[J]. J Athl Training, 1999, 34(02): 86~92.

[6] De Gwinn, Jh Wilckens, Er Mcdevitt, et al. The relative incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury in men and women at the United States Naval Academy[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 2000, 28(01): 98~102.

[7] Am Gray, Z Gugala, Jg Baillargeon. Effects of Oral Contraceptive Use on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Epidemiology[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2016, 48(04): 648~654.

[8] L Dragoo Jason, Kevin Padrez, Rosemary Workman, et al. The effect of relaxin on the female anterior cruciate ligament: Analysis of mechanical properties in an animal model[J]. The Knee, 2009, 16(01): 69~72.

[9] Ja Konopka, Mr Debaun, W Chang, et al. The Intracellular Effect of Relaxin on Female Anterior Cruciate Ligament Cells[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 2016, 44(09): 2384~2392.

[10] Jl Dragoo, Rs Lee, P Benhaim, et al. Relaxin receptors in the human female anterior cruciate ligament[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 2003, 31(04): 577~584.

[11] Sh Liu, R Al-Shaikh, V Panossian, et al. Primary immunolocalization of estrogen and progesterone target cells in the human anterior cruciate ligament[J]. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society, 1996, 14(04): 526~533.

[12] G Myklebust, S Maehlum, I Holm, et al. A prospective cohort study of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in elite Norwegian team handball[J]. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 1998, 8(03): 149~153.

[13] G Ruedl, P Ploner, I Linortner, et al. Are oral contraceptive use and menstrual cycle phase related to anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female recreational skiers?[J]. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy: official journal of the ESSKA, 2009, 17(09): 1065~1069.

[14] Vollman R F. The Menstrual Cycle[J]. Major Problems in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1977, 7: 1~193.

[15] J Agel, B Bershadsky, Ea Arendt. Hormonal therapy: ACL and ankle injury[J]. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2006, 38(01): 7~12.

[16] Cs Samuel, A Butkus, Jp Coghlan, et al. The effect of relaxin on collagen metabolism in the nonpregnant rat pubic symphysis: the influence of estrogen and progesterone in regulating relaxin activity[J]. Endocrinology, 1996, 137(09): 3884~3890.

[17] U Wreje, P Kristiansson, H Aberg, et al. Serum levels of relaxin during the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptive use[J]. Gynecol Obstet Invest, 1995, 39(03): 197~200.

[18] Hur Hye-Chun. Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility, 7 th edition. Leon Speroff and Marc A. Fritz. ISBN 0-7817-4795-3, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004, 1334 pp[J]. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol, 2006, 19(03): 249~250.

[19] Zantop Thore, Petersen Wolf, Fu Freddie H. Anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament[J]. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics, 2005, 15(01): 0~28.

[20] Duthon Victoria Lysiane Agnes, Barea Christophe, Abrassart Sophie, et al. Anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament[J]. Folia Morphol(Praha), 2009, 68(01): 8~12.

[21] Md Rau, D Renouf, D Benfield, et al. Examination of the failure properties of the anterior cruciate ligament during the estrous cycle[J]. The Knee, 2005, 12(01): 37~40.

[22] P Sciore, Cb Frank, Da Hart. Identification of sex hormone receptors in human and rabbit ligaments of the knee by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction: evidence that receptors are present in tissue from both male and female subjects[J]. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society, 1998, 16(05): 604~610.

[23] Rm Lovering, Wa Romani. Effect of testosterone on the female anterior cruciate ligament[J]. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, 2005, 289(01): R15~22.

[24] Ja Konopka, L Hsue, W Chang, et al. The Effect of Oral Contraceptive Hormones on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Strength[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 2020, 48(01): 85~92.

[25] Sk Park, Dj Stefanyshyn, B Ramage, et al. Relationship between knee joint laxity and knee joint mechanics during the menstrual cycle[J]. Br J Sports Med, 2009, 43(03): 174.

[26] J Slauterbeck, C Clevenger, W Lundberg, et al. Estrogen level alters the failure load of the rabbit anterior cruciate ligament[J]. Journal of orthopaedic research: official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society, 1999, 17(03): 405~408.

[27] Bt Zazulak, M Paterno, Gd Myer, et al. The effects of the menstrual cycle on anterior knee laxity: a systematic review[J]. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 2006, 36(10): 847~862.

[28] Te Hewett, Bt Zazulak, Gd Myer. Effects of the menstrual cycle on anterior cruciate ligament injury risk: a systematic review[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 2007, 35(04): 659~668.

[29] Sh Liu, Ra Al-Shaikh, V Panossian, et al. Estrogen affects the cellular metabolism of the anterior cruciate ligament. A potential explanation for female athletic injury[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 1997, 25(05): 704.

[30] J Neugarten, A Acharya, J Lei, et al. Selective estrogen receptor modulators suppress mesangial cell collagen synthesis[J]. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology, 2000, 279(02): F309~F318.

[31] F Dehghan, Bs Haerian, S Muniandy, et al. The effect of relaxin on the musculoskeletal system[J]. Scand J Med Sci Sports, 2014, 24(04): e220~e229.

[32] Zimmerman Ellen, Parlee Mary Brown. Behavioral Changes Associated with the Menstrual Cycle: An Experimental Investigation[J]. 1973, 3(04): 335~344.

[33] R Sarwar, Bb Niclos, Om Rutherford. Changes in muscle strength, relaxation rate and fatiguability during the human menstrual cycle[J]. The Journal of physiology, 1996: 267~272.

[34] Hs Thompson, Jp Hyatt, Mj De Souza, et al. The effects of oral contraceptives on delayed onset muscle soreness following exercise[J]. Contraception, 1997, 56(02): 59~65.

[35] Gp Kenny, E Leclair, Rj Sigal, et al. Menstrual cycle and oral contraceptive use do not modify postexercise heat loss responses[J]. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 2008, 105(04): 1156~1165.

[36] U Wreje, J Brynhildsen, H Aberg, et al. Collagen metabolism markers as a reflection of bone and soft tissue turnover during the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptive use[J]. Contraception, 2000, 61(04): 265~270.

[37] Wd Yu, V Panossian, Jd Hatch, et al. Combined effects of estrogen and progesterone on the anterior cruciate ligament[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2001(383): 268~281.

[38] J Möller Nielsen, M Hammar. Sports injuries and oral contraceptive use. Is there a relationship?[J]. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 1991, 12(03): 152~160.

[39] Pa Martineau, F Al-Jassir, E Lenczner, et al. Effect of the oral contraceptive pill on ligamentous laxity[J]. Clinical journal of sport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy of Sport Medicine, 2004, 14(05): 281~286.

[40] L Rahr-Wagner, Tm Thillemann, F Mehnert, et al. Is the use of oral contraceptives associated with operatively treated anterior cruciate ligament injury? A case-control study from the Danish Knee Ligament Reconstruction Registry[J]. The American journal of sports medicine, 2014, 42(12): 2897~2905.

[41] Df Lobato, M Baldon Rde, Py Wun, et al. Effects of the use of oral contraceptives on hip and knee kinematics in healthy women during anterior stair descent[J]. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 2013, 21(12): 2823~2830.

[42] Jh Kim, Sk Lee, Sk Lee, et al. Relaxin Receptor RXFP1 and RXFP2 Expression in Ligament, Tendon, and Shoulder Joint Capsule of Rats[J]. J Korean Med Sci, 2016, 31(06): 983~988.

Effects of Oral Contraceptive Use on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk in Female Athletes

YANG Lu1, XU Yan1,2

1.R&D Department, Nanjing Sport Institute, Nanjing Jiangsu, 210014, China;2.R&D Department, Nanjing Regenerative Medicine Engineering and Technology Research Center, Nanjing Jiangsu, 210046, China.

The anterior cruciate ligament injury is very common in the sports population. With the development of competitive sports and the popularization of mass sports in china, the incidence of ACL injury is obviously increased. Because of the influence of hormones, the incidence of female athletes ACL injury is significantly higher than that of male athletes in various sports. The short- and long-term consequences of ACL injuries—including reconstructive surgery, long-term rehabilitation, and premature osteoarthritis—are costly. Prevention of ACL injury is critical in view of its negative impact on individuals and society. This review reviewed the mechanism of the effect of hormones on ACL injury in female athletes. On this basis, we explored the impact of oral contraceptives on the risk of ACL injury and the future research direction.

Anterior cruciate ligament; Oral contraceptive; Hormones; Matrix metalloproteinase; RISK of injury; Cognitive progress

1007―6891(2022)02―0054―05

10.13932/j.cnki.sctykx.2022.02.12

2020-05-19

2021-06-15

徐妍,女,1980-,讲师,学科研究方向:干细胞诱导及损伤修复。

804.55

A