Influence of overweight and obesity on the mortality of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia

INTRODUCTION

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a lower respiratory tract infection due to one or more pathogens acquired outside of a hospital setting[1]. This contrasts with pneumonia acquired within the hospital setting, including nosocomial pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia[1]. The incidence of CAP ranges from 10.6 to 44.8 cases per 1000 person-years and increases with age[2]. CAP risk factors include age, smoking, chronic comorbidities (such as diabetes mellitus and chronic lung, renal, heart, or liver disease), orodental/periodontal disease, treatment with proton pump inhibitors, prescription opioids, and high alcohol consumption[3-5]. Pathogens that cause CAP include respiratory viruses,(),,,,,species,, and Gram-negative rods[6,7]. Complications of pneumonia include parapneumonic effusion, empyema, lung abscess, sepsis, and cardiac complications, such as heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and acute coronary syndromes[8,9]. Lower respiratory tract infections are among the top 4 causes of death, and the most common infectious cause of death, worldwide[10]. The mortality rate is highly variable, ranging from < 1% to > 30%, depending on comorbidities and findings at presentation[11-13].

The prognostic factors for CAP include sex, cognitive symptoms, high urea levels, high respiratory rate, low blood pressure, age ≥ 65 years, comorbidities (cancer, chronic liver disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, and chronic renal disease), and low or higher body temperature[14,15]. Obesity is associated with increased morbidity and mortality, including increased risk of cardiovascular events and increased risk of certain cancers[16-18].

Nevertheless, several studies have shown that the mortality of obese individuals is reduced in various diseases, a phenomenon that is referred to as the “obesity survival paradox”[19]. Lacroix[20] found a negative correlation between body mass index (BMI) and pneumonia mortality in an observational study of 2600 middle-aged American men. In a cohort study of 110000 Japanese adults, BMI (≥ 25 kg/m) had a protective effect on pneumonia mortality [odds ratio (OR) = 0.7, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.5-0.8][21]. Thus, in some diseases, obesity has emerged as a protective factor that could improve prognosis and reduce mortality[22-24]. Nevertheless, conflicting results are found in the literature[25,26]. In pneumonia caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, obesity is associated with worse outcomes[27], but the present study investigated “classical” CAP, not coronavirus disease 2019.

16. Unhappy girl that I am: The heroine s repentance58 comes because of her poor status and, perhaps, actually seeing the wealth of King Thrushbeard makes her realize what she refused. Von Franz states that such regret is typical of the animus driven woman, and is pseudo guilt59 and sterile60 (173).Return to place in story.

Alan woke up at 4:30 on Tuesday for his morning flight to San Francisco. As he kissed our five-year-old daughter Sonali and me good-bye, I pulled him toward me, knocking him over. He laughed heartily4 and said, I ll return with the pot of gold.

Previous studies on the relationship between obesity, pneumonia, and mortality have yielded intriguing observations. For example, an early study by Lacroix[20] showed a negative correlation between BMI and pneumonia-associated mortality in an observational study of 2600 middle-aged American men. In a prospective study of 110 thousand Japanese adults, it was also found that BMI ≥ 25 kg/mpromoted a protective effect in the context of pneumonia-associated mortality[21], and the trend between BMI and CAP mortality showed a significant inverse relationship (< 0.001). Braun[50] found that in 763 patients, the 64 obese patients (BMI > 30 kg/m) had a significantly lower 6-year all-cause mortality compared with normal-weight patients (BMI 18.5-25 kg/m). Other studies also report similar results[22-24], supporting the present study. Nevertheless, some points still remain to be clarified. Indeed, Kornum[25] showed that males were at a higher risk of hospitalization than females, which was not observed in the present study. In addition, the relationship between obesity and clinical outcomes appears to be different between children and adults[26], but the present study did not include children.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patients

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Qinhuangdao, and all participants provided written informed consent. This retrospective study included patients with CAP hospitalized in the First Hospital of Qinhuangdao from June 2013 to November 2018.

All patients were diagnosed with CAP according to the clinical guidelines developed by the Respiratory Society of the Chinese Medical Association[28]. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP;, pneumonia at 48 h after admission); (2) Pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary tumors, non-infectious pulmonary interstitial disease, pulmonary edema, atelectasis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary eosinophilic infiltration, and pulmonary vasculitis caused by other factors, < 18 years of age; or (3) Immunosuppression, which was defined as current, 28-d use of oral prednisolone at any dose, or other immunosuppressive drugs (, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and anti-TNF-α agents), or patients known to have received solid organ transplantation.

The demographic and clinical characteristics, laboratory biochemical indicators measured for the first time after admission, and other risk factors [including a history of diabetes, use of a ventilator during the disease, and transfer to intensive care unit (ICU)] were collected from the hospital medical record database, and whether the patient terminated hospitalization due to death-an event that was duly recorded. The normal value of white blood cells (WBC) was 3.5-9.5 × 10/L. The normal value of neutrophils (NEUT) was 1.8-6.3 × 10/L. The normal value of C-reactive protein (CRP) was 0-10 mg/L. The normal value of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was 2.86-8.20 mmol/L. The normal value of albumin (ALB) was 35.0-55.0 g/L. Death of the patient was queried through the medical record system. If the patient’s discharge order was death, then the patient was considered an in-hospital death. Death was judged based on respiratory and cardiac arrest, not including brain death.

At first I was grieved to see Lolotte cry, resumed the Princess, but I soon found that grieving was very troublesome, so I thought it better to be calm, and very soon afterwards I saw the Fairy Mirlifiche arrive, mounted upon her great unicorn110

Assessment of BMI

All patients had their weight and height measured on admission as part of a nutritional risk assessment score. BMI was calculated as height/weight. Patients were classified into BMI subgroups: (1) Underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m); (2) Normal weight (BMI 18.5-23.9 kg/m); and (3) Overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 24 kg/m)[29].

Patient assessment

As a general rule, obesity is associated with a higher risk of surgical-site infections, nosocomial infections, periodontitis, skin infections, and acute pancreatitis[45,46]. In overweight patients, there are recognized changes that include hypoxia, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance. Immune cells adapt to an altered tissue microenvironment by adapting their metabolism, eventually leading to an immune response imbalance, chemotaxis damage, and immune cell differentiation[47]. The relationship between obesity and chronic respiratory diseases, including obstructive sleep apnea and obesity hypopnea syndrome, has also been well described[48]. Obese patients show lung function changes, including decreased lung volume, reduced respiratory compliance, reduced gas exchange, impaired respiratory muscle function, and increased airway resistance[49]. Given that these clinical manifestations collectively indicate an increased risk of infection with bacterial and viral pathogens and drive potential changes in lung function, it is logical to theorize that obese patients would be at increased risk for both the development of pneumonia and for much worse clinical outcomes. It can be intuitively assumed that obese patients are more likely to exhibit adverse clinical outcomes and an increased mortality secondary to pneumonia.

Outcome

The primary outcome was all-cause hospital mortality, defined as the ratio of the total number of deaths from all causes during the study period to the total number of people included in the study.

Data collection and definitions

I ducked down behind the shoe mirror as they headed toward the golf ball section. Would they buy the Tour Edition Titleists? Probably not without help. I dashed down the club display aisle6 and slipped behind the mountain of shimmering7 red and gold boxes.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States). Data are expressed as medians (interquartile range) or a numerical value with percentage. When data were not normally distributed, the values were log-transformed for analysis. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s-test (two groups) or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the least significant difference post hoc test (more than two groups). Multiple logistic regression analyses were used to examine the association between the survival state and the observation index. Statistical significance was established at< 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patients according to BMI

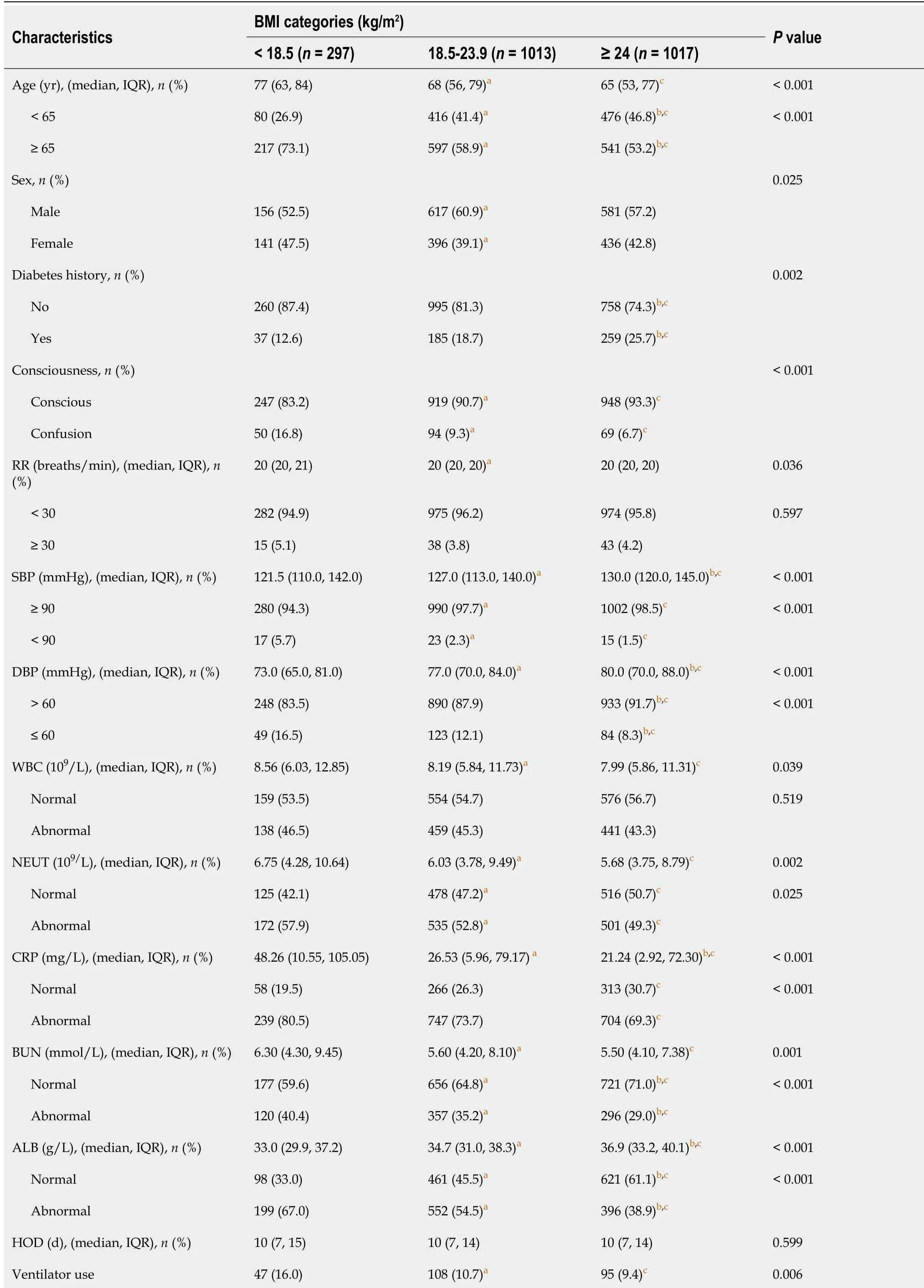

This study identified 2500 patients with CAP, of which 2327 patients had available BMI data (173 patients were excluded due to a lack of BMI data). There were 297 (12.8%) underweight patients, 1013 (43.5%) with a normal weight, and 1017 (43.7%) overweight/obesity (Table 1). There were statistically significant differences among the three groups in terms of age, sex, diabetes history, consciousness, SBP, DBP, NEUT, CRP, BUN, ALB, use of a ventilator, CURB-65 score, ICU admission, and death (all< 0.05). Mortality was lowest in the overweight/obesity group and highest in the underweight group (overweight/obesity: 2.8%,normal: 5.0%,underweight: 9.1%,< 0.001). According to the CURB-65 class, the number of low-risk CAP cases was highest in the overweight/obesity group (overweight/obesity: 73.2%,normal: 66.6%,underweight: 52.5%,< 0.001). Accordingly, the proportion of patients admitted to the ICU was lowest in the overweight/obesity group (overweight: 12.1%,normal: 18.0%,underweight: 20.5%,< 0.001).

Some infection indicators, such as WBC, NEUT, CRP, and BUN, were higher in the underweight group than in the overweight group. The ALB levels in the underweight group were lower than in the overweight/obesity group [median, 33.036.9 g/L,< 0.001. The proportion of patients with confusion was higher in the underweight group than in the overweight/obesity group) 16.8%6.7%,< 0.001]. The history of diabetes in the overweight/obesity group was higher than in the underweight group (25.7%12.6%,< 0.001).

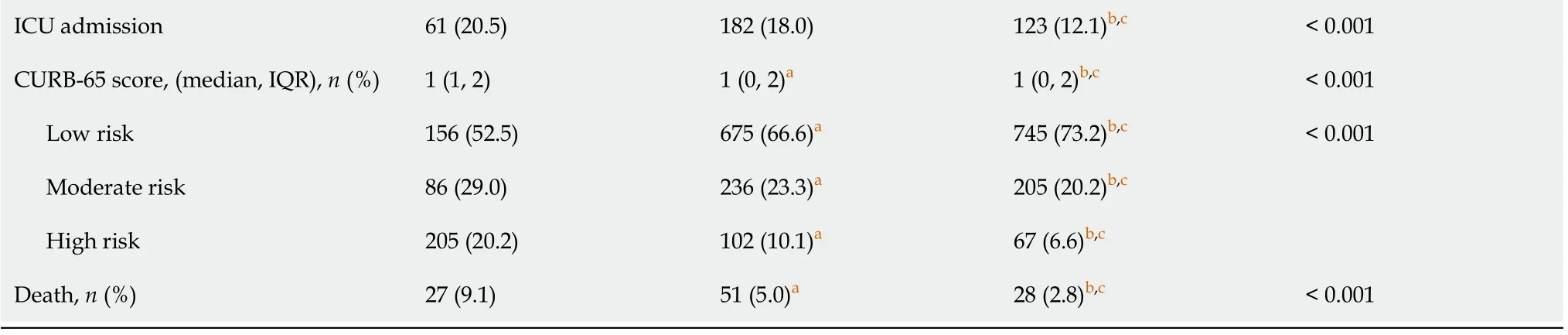

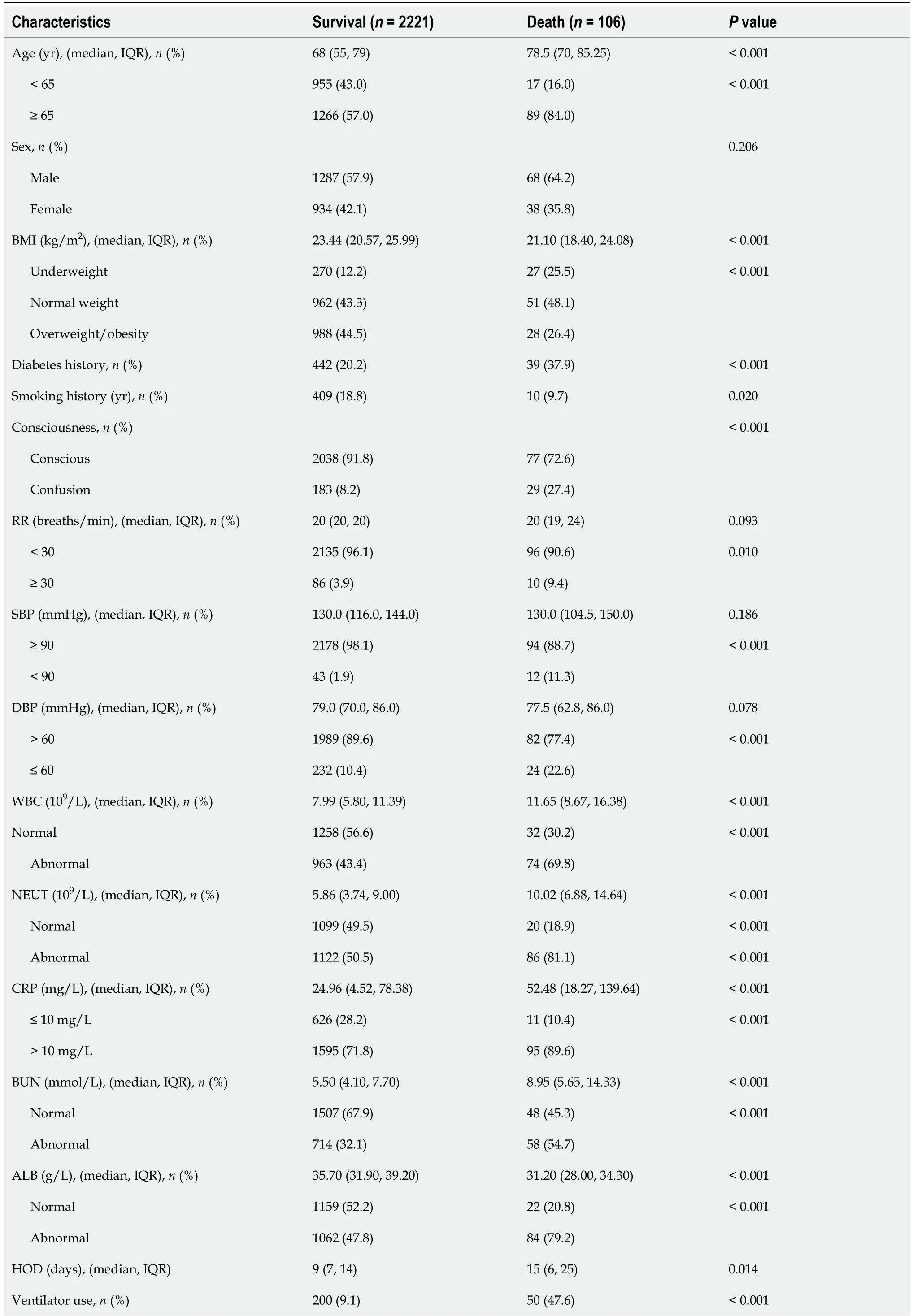

Characteristics of the patients according to survival

Table 2 shows the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 2327 patients with CAP and according to mortality. The < 65-year-old patients represented 43.0% of the survivors, compared with 57.0% for those > 65 years old (< 0.001). The overweight/obesity group’s survival rate was higher than that of the underweight group (44.5%12.2%,< 0.001). The patients with a history of diabetes represented 37.9% of the deaths. According to the CURB-65 score, the high-risk group had the lowest survival rate, while the low-risk group had the highest survival rate (< 0.001).

Compared with the non-survival group, the survival group was less likely to spend time in the ICU (14.0%52.8%,< 0.001). In addition, the hospital days and the frequency of ventilator use in the non-survival group were higher than in the survival group (both< 0.05). The levels of WBC, NEUT, CRP, and BUN in the death group were higher than in the survival group (all< 0.001). Finally, ALB levels in the survival group were higher than in the mortality group (< 0.001).

This study has limitations. The patients were all from a single hospital. Therefore, when considering the relatively high incidence of CAP, the sample size was relatively small. In addition, it included only hospitalized patients and did not include patients with mild pneumonia and those who returned home with antibiotics. Finally, due to the study’s retrospective nature, only all-cause mortality could be examined, and CAPspecific mortality should be investigated in the future. Additional studies are still necessary to examine the prognostic factors of CAP.

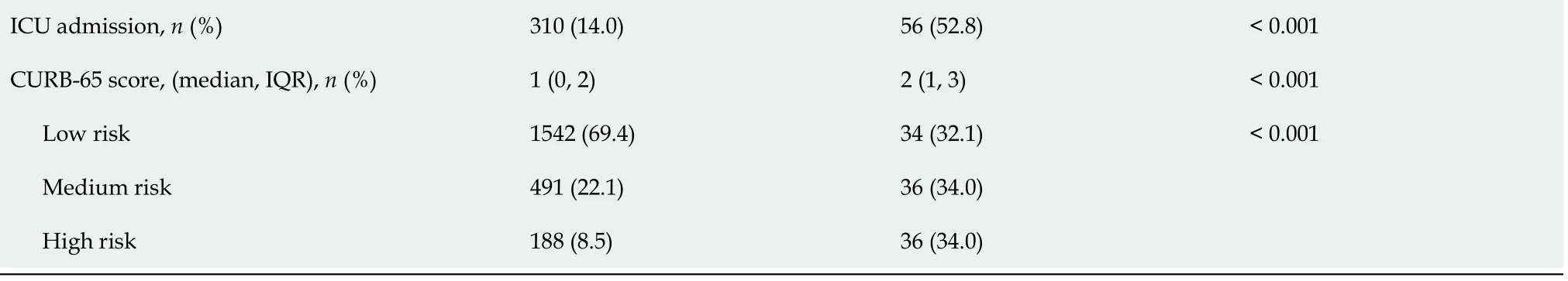

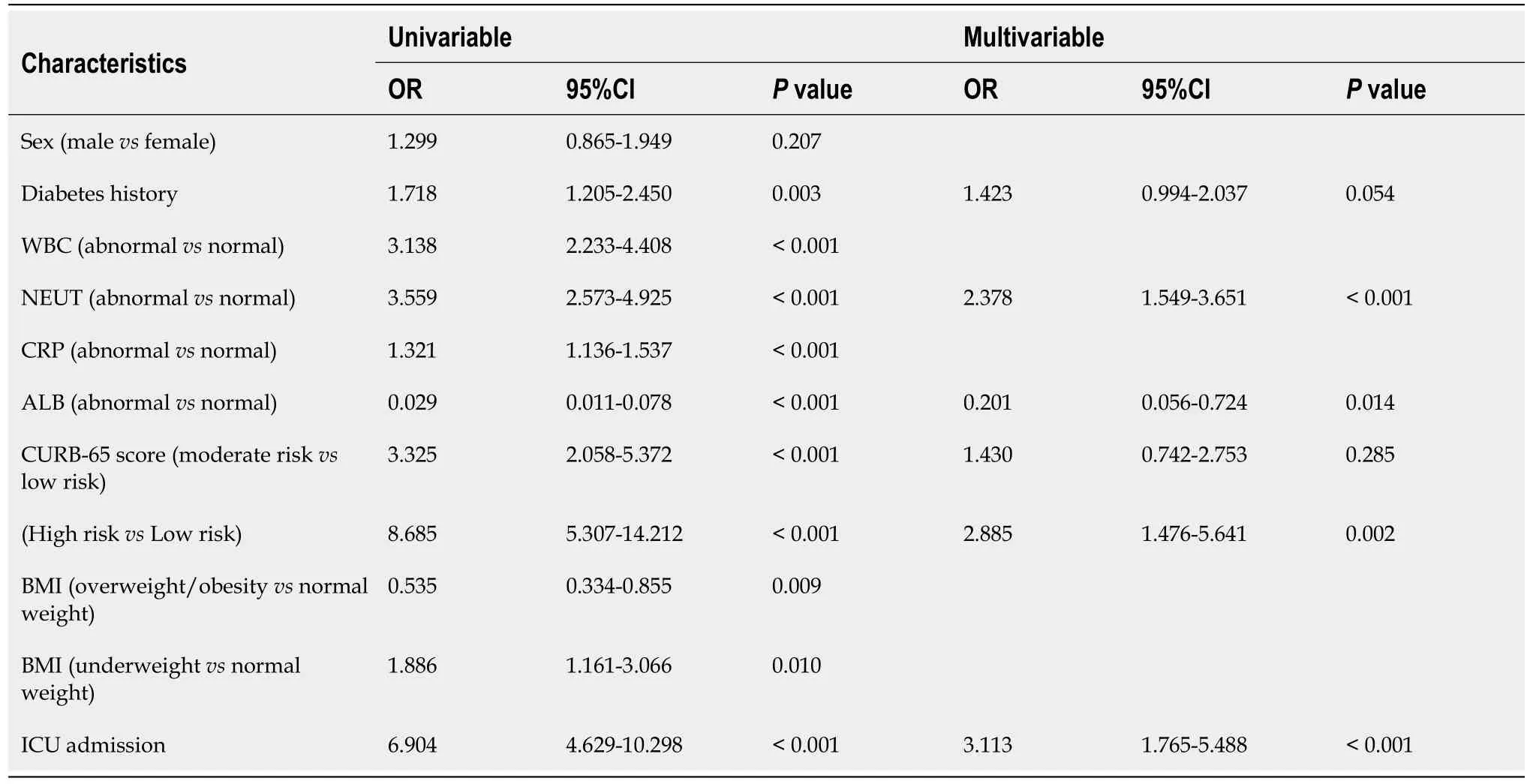

Multivariable analysis

Table 3 shows univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses for inhospital mortality of 2327 patients with CAP. The univariable analyses showed that diabetes history, WBC, NET, CRP, ALB, CURB-65 risk stratification, BMI, and ICU admission were significantly associated with all-cause mortality (all< 0.05). In the univariable analyses, the all-cause mortality of overweight/obesity patients was lower than that of normal-weight patients (OR = 0.54, 95%CI: 0.33-0.86,= 0.009), while the all-cause mortality of underweight patients was higher than that of normal-weight patients (OR = 1.89, 95%CI: 1.16-3.07,= 0.010). The multivariable analysis showed that abnormal NEUT counts (OR = 2.38, 95%CI: 1.55-3.65,< 0.001), abnormal ALB levels (OR = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.06-0.72,= 0.014), high-risk CURB-65 score (OR = 2.89, 95%CI: 1.48-5.64,= 0.002), and ICU admission (OR = 3.11, 95%CI: 1.77-5.49,< 0.001) were independently associated with mortality in patients with CAP.

DISCUSSION

Although obesity is associated with increased mortality due to multiple causes[16-18], it is associated with a better prognosis in patients with CAP (the so-called obesity survival paradox)[19-24]. However, conflicting results have been found[25,26], especially regarding the categories of patients at risk of higher mortality. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the relationship between all-cause mortality and BMI in patients with CAP. The results strongly suggested that overweight/obesity patients accounted for the largest proportion of CURB-65 low-risk patients with CAP. The allcause mortality of overweight/obesity patients was lower than that of normal-weight patients and NEUT counts, ALB levels, CURB-65 score, and ICU admission were independently associated with mortality in patients with CAP.

This study showed that abnormal NEUT counts were independently associated with a poor prognosis of CAP, which is already well-known[31-34]. Hypoalbuminemia is a well-known marker of adverse prognosis in a number of conditions and can be the result of various underlying conditions such as sepsis, cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, protein-losing enteropathy, malnutrition, and frailty[35]. Hypoalbuminemia is also associated with a poor prognosis in hospitalized patients[35,36] and in those with CAP[37,38]. The CURB-65 score is a well-known scoring system for the prognosis of pneumonia in the ICU setting[39,40]. It is based on confusion, uremia, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and age, and it can be used to guide management[41]. Finally, of course, ICU admission indicates a severe condition with a higher likelihood of a poor outcome[42-44].

Severity assessment scores on admission included the CURB-65 score (, disturbance of consciousness, urea > 7 mmol/L, respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/min, systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 90 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≤ 60 mmHg, age ≥ 65 years old)[30]. One point was allocated for each item, five points in total. A score of 0-1 points indicated low risk, 2 points indicate moderate risk, and 3-5 points indicated high risk[30].

Nevertheless, the risk of developing CAP in obese individuals is lower than in the general population[3,46]. BMI and the prognosis of pneumonia have recently emerged as a subject of increased and intense study[19-26]. The present study confirms that overweight/obesity patients actually have lower all-cause mortality. This is consistent with the fact that the inflammatory indices of overweight/obesity patients were lower than those of underweight patients, and the majority of overweight/obesity patients were at low CURB-65 risk. Similarly, overweight/obesity patients do not have a higher ICU occupancy rate. On the contrary, underweight patients are more likely to be admitted to the ICU.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between BMI and all-cause mortality of CAP and to examine the mechanism of overweight/obesity as a protective factor in CAP prognosis. The results could help our understanding and management of CAP.

Some hypotheses can be formulated to try to explain these results. One of the protective factors involved in the better prognosis of CAP in obesity might be an increase in the relative number and frequency of circulating M1 macrophages in overweight patients. Indeed, in an animal model, the content of macrophages in adipose tissue was positively correlated with adipocyte volume and the extent of obesity[51]. Under the regulation of chemokines, inflammatory factors, and free fatty acids in adipose tissue of obese people, IKKS, which is the activator of NF-κB in macrophages, activates the signal pathwayphosphorylation of p65, which stimulates a greater number of macrophages to display the M1 sub-type[52]. The increased number of M1 macrophages form a coronal aggregate that expands around the necrotic adipocytes to form similar foam cells, opening lysosomes and autophagic pathways, allowing macrophages to absorb and degrade the ectopic accumulation of lipid[53]. M1 macrophages can also reduce the acute inflammatory response by increasing PPAR-γ activation, autophagy, and lipid oxidation[54]. There is also hyperleptinemia in obese patients, which is involved in innate and acquired immunity and increases the activity of macrophages, chemotaxis of neutrophils, cytotoxicity of natural killer cells, and the production of T and B cells[55]. This activation of all immune cells could promote bacterial clearance. In an animal model reported in 2007, Hsu[56] found that ob/ob mice had a leptin deficiency. Using wild-type mice as controls, both the ob/ob and wild-type strains were infected with. It was found that the ob/ob mice had higher mortality and lower lung bacterial clearance rate, which was related to an impaired phagocytic function of the alveolar macrophages, decreased pulmonary neutrophil counts, and a decrease in bioactive proinflammatory cytokines. Exogenous leptin increased the survival rate and lung bacterial clearance rate of ob/ob mice.

King Cloverleaf and Queen Frivola had but one child, and this Princess had from her very babyhood been so beautiful, that by the time she was four years old the Queen was desperately2 jealous of her, and so fearful that when she was grown up she would be more admired than herself, that she resolved to keep her hidden away out of sight

A systematic analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials (= 1954) of glucocorticoids for adult CAP showed that glucocorticoids significantly reduced mortality [risks ratio (RR): 0.58, 95%CI: 0.40-0.4] and significantly lowered the early clinical failure rate in adults with severe CAP (RR: 0.32, 95%CI: 0.15-0.7)[57]. Glucocorticoids shorten the clinical cure time, hospital stay, and ICU stay time and reduce the incidence of pneumonia-associated complications. Glucocorticoids play a key role in anti-viral functions, the immune response, and display anti-inflammatory properties and promote other physiological functions, such that the symptoms of pulmonary parenchyma edema can be relieved in the early stages of inflammation. In the recovery period, glucocorticoids can effectively inhibit the proliferation of capillaries, downregulate collagen, inhibit the proliferation of granulation tissue and scar formation in the lung, and avoid pulmonary fibrosis. In addition, glucocorticoids can combine with lipopolysaccharide, which is the main component of Gram-negative bacterial endotoxins, so that it can effectively reduce the damage caused by endotoxins and relieve the corresponding symptoms. At the same time, it can also improve the microcirculation of patients, effectively avoiding platelet aggregation and thus preventing the formation of thromboses. Studies have shown that glucocorticoids in obese people are higher than in the general population[58,59]. The endogen glucocorticoid axis might be another hypothesis for the results observed in the present study.

In the current study, BMI could not be included in the multivariable analysis because it was the variable that was covariant with the largest number of other variables included in the models. Indeed, being underweight is associated with hypoalbuminemia and an inflammatory condition and with a poor prognosis in a variety of conditions[60-62]. Hence, the independent contribution of BMI to CAP mortality could be assessed, as it is an easy-to-determine factor that could be considered in patient management.

I told my friend Graham that I often cycle the two miles from my house to the town centre but unfortunately there is a big hill on the route. He replied, You mean fortunately. He explained that I should be glad of the extra exercise that the hill provided.

CONCLUSION

To investigate the relationship between all-cause mortality and body mass index (BMI)in patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Obesity is associated with a better prognosis in patients with community-acquired pneumonia (the so-called obesity survival paradox), but conflicting results have been found.

Research motivation

The inflammatory index and the severity of pneumonia in overweight/obesity patients with CAP were lower than in the normal-weight group, and the all-cause mortality was lower. NEUT counts, ALB levels, CURB-65 score, and ICU admission were independently associated with mortality in patients with CAP.

Research objectives

To investigate the relationship between all-cause mortality and BMI in patients with community-acquired pneumonia.

Research methods

This retrospective study included patients with community-acquired pneumonia hospitalized at the First Hospital of Qinhuangdao from June 2013 to November 2018.The patients were grouped as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-23.9 kg/m2), and overweight/obesity (≥ 24 kg/m2). The primary outcome was all-cause hospital mortality.

Then you can rot at the bottom of the sea, both of you, said the old woman; and perhaps it may be the case that your mother would rather keep the two sons she has than the one she hasn t got yet

Research results

Among 2327 patients, 297 (12.8%) were underweight, 1013 (43.5%) normal weight, and 1017 (43.7%) overweight/obesity. The all-cause hospital mortality was 4.6%(106/2327). Mortality was lowest in the overweight/obesity group and highest in the underweight group (2.8% vs 5.0% vs 9.1%, P < 0.001). All-cause mortality of overweight/obesity patients was lower than normal-weight patients [odds ratio (OR)= 0.535, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.334-0.855, P = 0.009], while the all-cause mortality of underweight patients was higher than that of normal-weight patients (OR= 1.886, 95%CI: 1.161-3.066, P = 0.010). Multivariable analysis showed that abnormal neutrophil counts (OR = 2.38, 95%CI: 1.55-3.65, P < 0.001), abnormal albumin levels(OR = 0.20, 95%CI: 0.06-0.72, P = 0.014), high-risk Confusion-Urea-Respiration-Blood pressure-65 score (OR = 2.89, 95%CI: 1.48-5.64, P = 0.002), and intensive care unit admission (OR = 3.11, 95%CI: 1.77-5.49, P < 0.001) were independently associated with mortality.

13.Her old grandmother, the only person who had loved her: Andersen also had a grandmother who doted on him, whom he remembered fondly in his memoirs39 and honors in this tale.Return to place in story.

Research conclusions

All-cause mortality of normal-weight patients was higher than overweight/obesity patients, and lower than that of underweight patients. Neutrophil counts, albumin levels, Confusion-Urea-Respiration-Blood pressure-65 score, and intensive care unit admission were independently associated with mortality in patients with communityacquired pneumonia.

“Even though I died right there in prison, I want to tell you something. The reason I need to talk to you today. I have risen again, just like in the Bible. I am reborn. One day a woman came in and told me to write. And I had never written before, but I did it anyway. I sat for eight ours in a chair and focused the way I have never focused before. I could never even sit still before! I wrote out my ugly life, and then I was able to finally feel something. To feel pity. For myself. When no one else was ever able to feel it. And I felt something else. I felt joy. I was writing, and what I was writing was good. I was a writer! And I was going to get up in front of all those men in that class, and I would say that this . . .” At these words he held up his little manuscript. This is more important to me than any drug. What I wanted to tell you was that I died a drug addict16, and I was reborn as a writer.”

Research perspectives

This study found that the all-cause mortality of community-acquired pneumonia in overweight or obese patients was lower than that in normal-weight patients, and the infection index was lower than that in normal-weight patients. The sample size in this study was large, and it breaks the traditional BMI grouping method. The grouping method of this study is consistent with the traditional grouping method.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all study participants who were enrolled in this study.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年1期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Hepatitis B virus reactivation in rheumatoid arthritis

- Paradoxical role of interleukin-33/suppressor of tumorigenicity 2 in colorectal carcinogenesis: Progress and therapeutic potential

- Changes in rheumatoid arthritis under ultrasound before and after sinomenine injection

- Benefits of multidisciplinary collaborative care team-based nursing services in treating pressure injury wounds in cerebral infarction patients

- Outcomes and complications of open, laparoscopic, and hybrid giant ventral hernia repair

- Surgical resection of intradural extramedullary tumors in the atlantoaxial spine via a posterior approach