Distribution of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 channels in gastrointestinal tract of patients with morbid obesity

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is an important public health problem that leads to chronic diseases, increasing mortality and morbidity[1]. Along with the increase in obesity, which is associated with metabolic dysfunctions and chronic inflammation, there has also been an increase in obesity-related diseases such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, asthma, some cancers, and psychological problems[2,3]. Preventing obesity or ensuring weight loss in patients will reduce these health problems[4,5]. However, the efficacy of behavioral, pharmacological, and surgical approaches in morbidly obese individuals is limited due to problems with implementation and severe side effects of drugs[6-8]. Surgical approaches are invasive and expensive, and long-term effects are unknown[9,11]. Due to the inadequacy of existing treatment methods in most cases and the fact that many surgical methods can cause serious complications, an effective, safe, widely available, and easily usable alternative anti-obesity treatment option is necessary for the prevention and treatment of obesity.

At the end of the party, he invited her to have coffee with him, she was surprised but due2 to being polite, she promised. They sat in a nice coffee shop, he was too nervous to say anything, she felt uncomfortable, and she thought to herself, Please, let me go home...

Prince Vivien was fully11 aware of the feeling in his favour, but being too honourable12 to wish to injure his pretty cousin, and perhaps too impatient and volatile13 to care to think seriously about anything, he suddenly took it into his head that he would go off by himself in search of adventure

Capsaicin, which is found in pepper and causes a bitter taste, has recently been shown to be an anti-obese agent in animal studies, with few studies conducted in humans, and data on obese and morbidly obese patients are limited[12]. Transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1), a nonselective cation channel, is mainly found in neuronal tissue and has also been shown to be present in adipose tissue and skeletal muscles and mediates the effect of capsaicin on adipose tissue[13-16]. Previous rodent studies have shown that approximately 80% of capsaicin is passively absorbed in the gastrointestinal and upper small intestinal segments, and dietary capsaicin consumption triggers an increase in intestinal mucosal afferent nerve activation and intestinal blood flow through TRPV1[17,18]. In addition to gastrointestinal tract (GIT) effects, capsaicin inhibits adipogenesis through TRPV1, mainly by acting on preadipocytes and adipocytes, inducing lipolysis and apoptosis[13,14]. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that TRPV1 activation with capsaicin may effectively prevent diet-induced obesity[19,20]. In human studies, dietary hot pepper supplementation increased thermogenesis and lipid oxidation, with a higher tendency to expend energy caused by beta-adrenergic stimulation[21,22]. Additionally, capsaicin decreased body weight, serum insulin levels, and HOMA-IR indices and increased insulin sensitivity in 50 overweight female patients[23]. However, capsaicin did not significantly change appetite or orexigenic-anorexigenic peptide levels in obese young people[24].

TRPV1 has been previously demonstrated by immunohistochemistry to be localized at nerve endings along the rat stomach wall (mucosa, submucosa, and muscle layer), and its functions have been investigated thoroughly; however, studies on human gastric tissue are scarce[26,27]. Previously, the presence of TRPV1 in neurons and parietal cells of gastric tissue in human samples was shown and suggested that TRPV1 regulates acid secretion and enhances local gastroprotection[28]. These findings are also supported by the present study in which we found high expression of TRPV1 in fundus parietal cells. Activation of TRPV1 increases intracellular calcium. The increase in intracellular calcium in parietal cells stimulates acid secretion. The acid secretionenhancing property of TRPV1 activation can be used for therapeutic purposes, especially in cases where basal acid secretion is reduced because of neurodegeneration, such as advanced age and diabetes[30]. TRPV1 activation in chief cells is also likely to enhance digestion since chief cells secrete pepsinogen, which is converted to pepsin in acidic environments and helps protein digestion. Our study found that TRPV1 expression on chief cells in the fundus was significantly higher in patients aged 45 years and older, suggesting that TRPV1 activation may benefit elderly patients with lower pepsin levels[30,31]

In mice, TRPV1 expression was shown in the nerve endings of the gastric mucosa, submucosa, and muscle layer[25-27]. Data on the TRPV1 distribution in human gastric mucosa are limited: TRPV1 has been previously shown in gastric parietal cells and antral glandular cells, and it was shown to affect gastrin levels[28,29]. However, there are no data on the TRPV1 distribution in the gastric and duodenal mucosal cells of obese people in comparison with normal-weight individuals. Previous studies have suggested a link between obesity and capsaicin-associated pathways, and activation of TRPV1 may provide an alternative approach for obesity treatment. It is also unknown whether the expression of TRPV1 changes in the upper GIT of obese and nonobese individuals and which cells express TRPV1 in the gastric and duodenal mucosal cells of humans. Determination of these factors can guide the creation of treatment approaches targeting TRPV1. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to clarify the gastric and duodenal mucosal expression of TRPV1 in humans and compare the TRPV1 expression profiles of obese and healthy individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, place, and time

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the expression of TRPV1 is similar in the gastroduodenal mucosa of morbidly obese patients and control subjects. TRPV1 expression was significantly higher in parietal and chief cells of the fundus and mucous and foveolar cells in the antrum, which affects digestion, mucosal protection, and motility. It is difficult to say that capsaicin, which is thought to act on the GIT, central nervous system, and adipocyte tissue triangle, exerts its anti-obesity effect through a single pathway. In addition, the unchanged expression of gastric and duodenal TRPV1 in the obese patient group suggests that drugs targeting TRPV1 may be effective in these patients. Further studies are needed in this area.

Subjects

Simultaneous biopsies from the fundus, antrum, and duodenum tissues were obtained from subjects between the ages of 18 and 65 who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy. For the study group, the inclusion criteria were a body mass index (BMI) of > 40 kg/m, and for the control group, patients with a BMI between 18-25 kg/mwere eligible to be included. The exclusion criteria were as follows: being treated for an indication of upper GIT bleeding, active peptic ulcer, active inflammatory/infectious condition during the procedure, a history of malignancy, and a history of upper GIT surgery. Forty-six patients with a BMI of > 40 kg/mand 20 patients with a BMI between 18-25 kg/mreferred for any indication of esophagogastroduodenoscopy were included in our study.

Data collection and analysis

Age, sex, history of alcohol and cigarette consumption, and past medical history regarding chronic diseases and medications were accessed from patient charts and were analyzed accordingly.

In a moment the Princess Hyacinthia had changed herself, the Prince, and his charger into a thick wood where a thousand paths and roads crossed each other

Herein, we aimed to investigate the distribution of TRPV1 in human gastroduodenal cells in morbidly obese patients and controls. TRPV1 expression was similar in the morbidly obese and control groups at all tissue sites. We found that TRPV1 expression was higher in the stomach than in the duodenum and was predominantly found in parietal and chief cells of the fundus and mucous and foveolar cells of the antrum. Interestingly, unlike foveolar cells in the antrum, TRPV1 was relatively low in foveolar cells in the fundus. In the duodenum, there was more intense staining in absorbent cells than in goblet and mucous cells. The mucous cells here also had low levels of TRPV1 compared to mucous cells in the antrum. Therefore, capsaicin possibly exerts its mucosal effectsTRPV1 in the stomach rather than the duodenum. We have also demonstrated that TRPV1 expression changes in a given cell type depending on the localization, demonstrating the phenotypic and possibly functional heterogeneity of a given cell type throughout the GIT. These findings also suggest that the sensitivity of the cells to TRPV1 activation differs depending on the localization.

Samples from fundus, antrum, and duodenum tissues of each case were prepared on a 4-micron-thick positively charged single slide for immunohistochemical staining. These tissue preparations were partially deparaffinized and placed in the device. Per the protocol, rabbit polyclonal anti-VR1 antibody (Abcam Cat No: AB111973) was used to stain the samples.

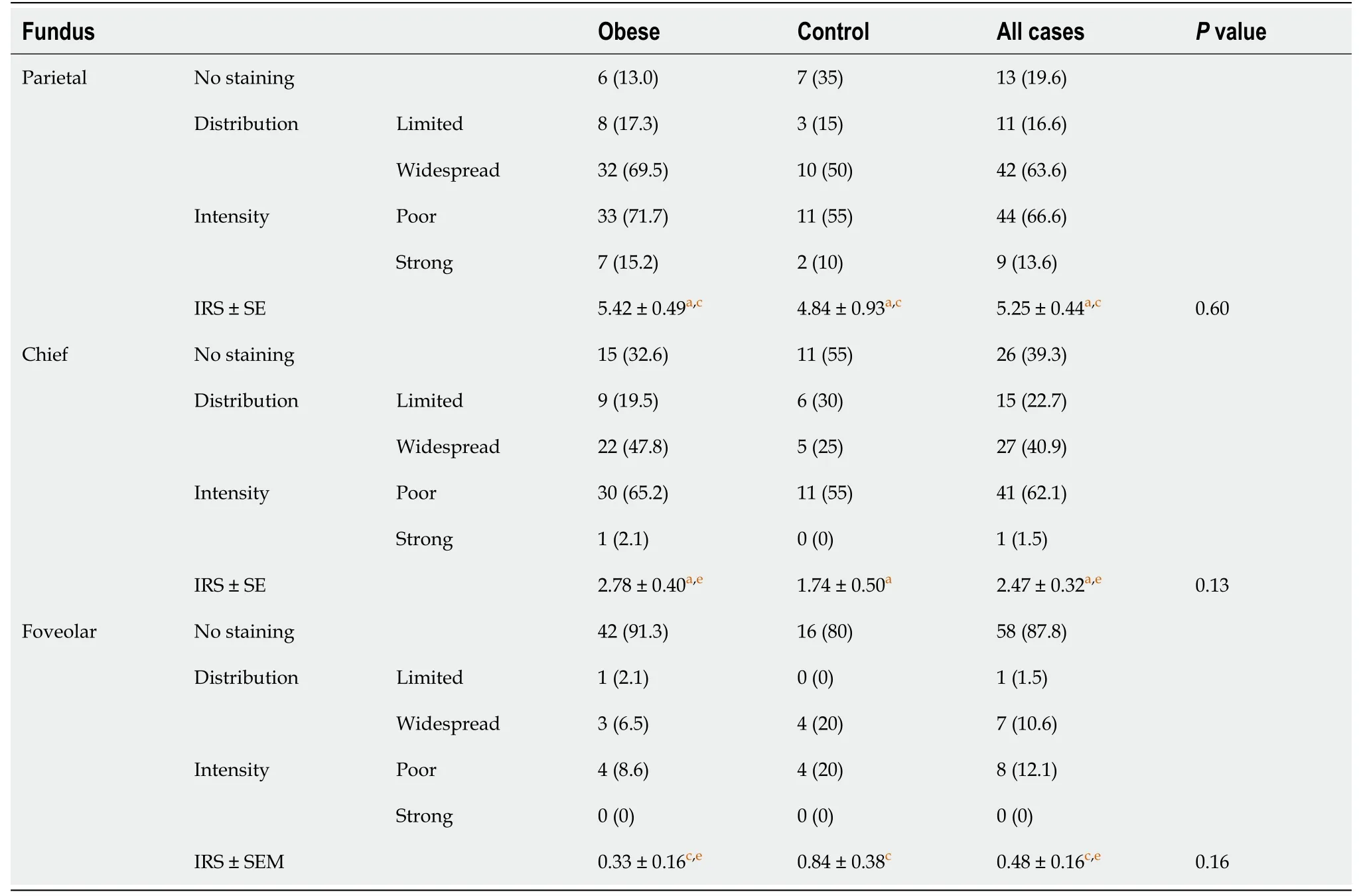

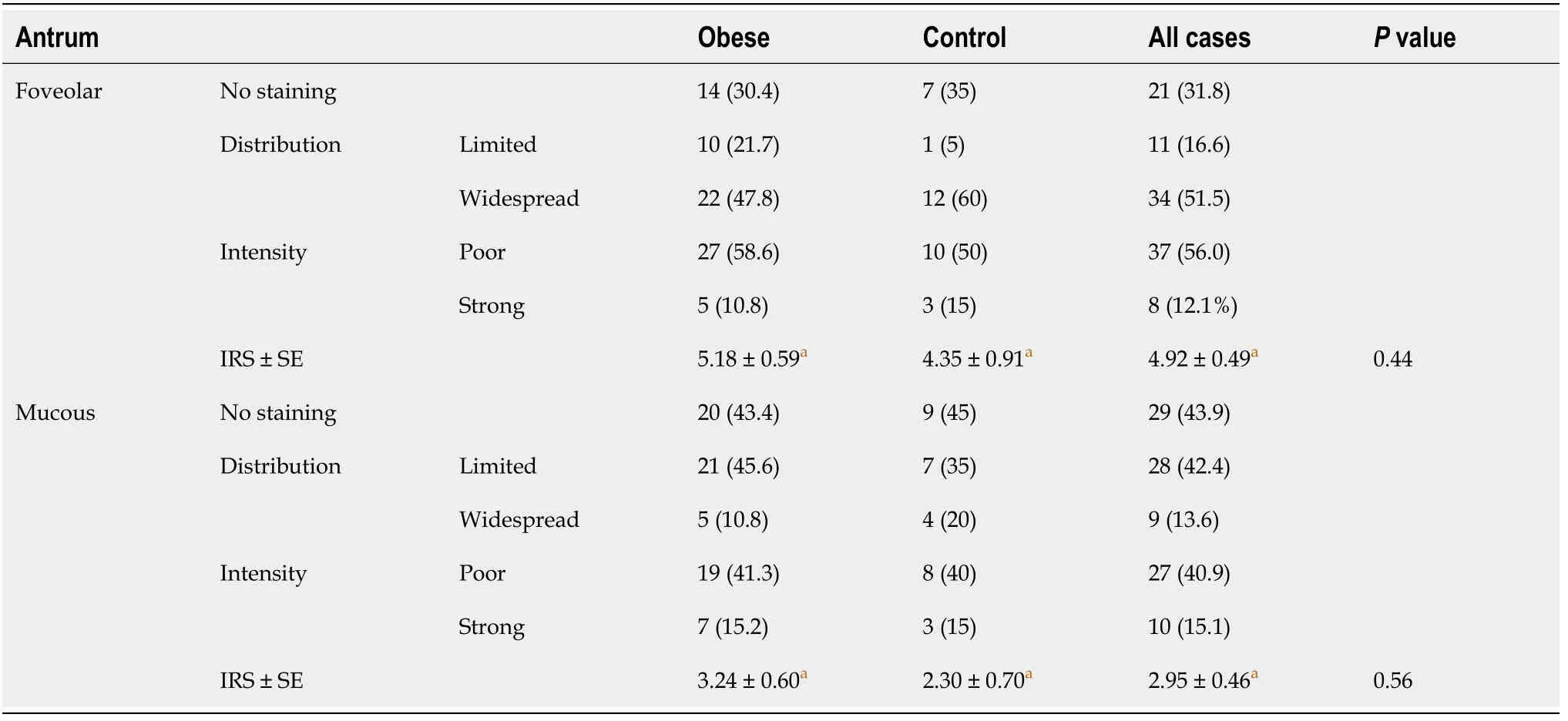

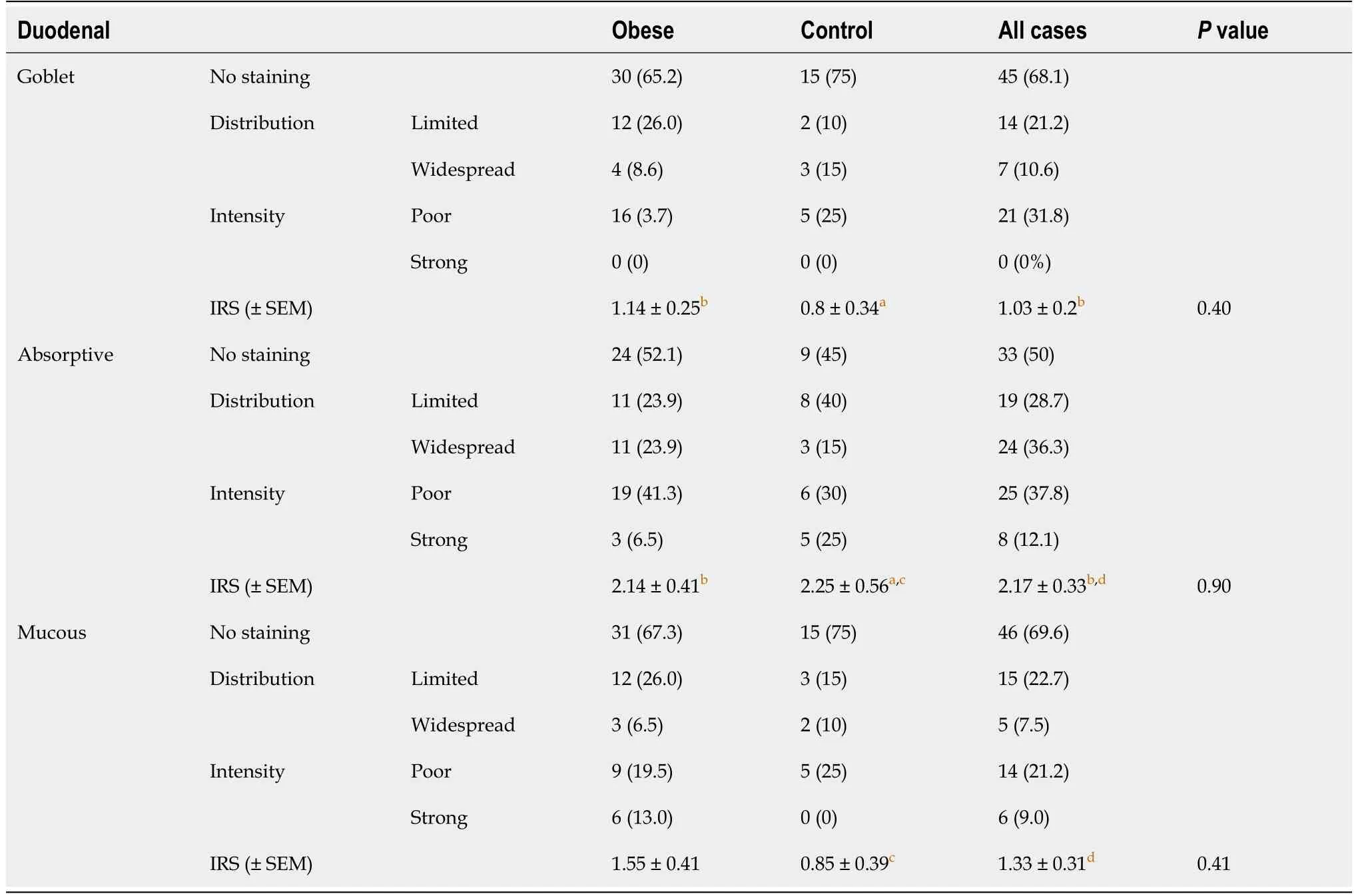

The IRS of the cells were also compared in their respective localizations. In the fundus, the highest IRS was seen in parietal cells, while the lowest occurred in foveolar cells among all three cell groups. Higher levels of TRPV1 expression were observed in parietal cells than in chief and foveolar cells, as demonstrated in Table 1. TRPV1 expression was lowest in foveolar cells in all cases (Table 1). In the antrum, foveolar cells stained more intensely than mucous cells (Table 2). In the duodenum, TRPV1 staining of absorptive cells was significantly higher than that of goblet cells, while TRPV1 staining of mucous and goblet cells was similar in both groups (Table 3). When the staining levels of the same type of cells in different tissues were compared, cells of the antrum had the highest staining intensity, followed by the fundus and duodenum. Specifically, foveolar cells in the antrum had higher IRS than foveolar cells in the fundus. Similarly, mucous cells in the antrum had higher IRS than mucous cells in the duodenum (Figure 2A and B).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed in the SPSS 17.0 package program. Continuous variables were evaluated by Shapiro-Wilk tests for normal distribution. Nominal and ordinal data are expressed as frequencies (percentages), and continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SE. Significant differences between the data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitneytest for independent variables and the Wilcoxon signed rank test for dependent variables. The thresholdvalue was accepted as 0.05 for statistical significance.

RESULTS

In this study, we included a total of 66 cases, specifically 46 cases of morbidly obese patients and 20 control cases. The mean age of the morbidly obese group was 45.2 ± 11.9, and that of the control group was 40.4 ± 13.0. Thirty-eight cases (82.6%) were female and 8 (17.4%) were male in the morbidly obese group, whereas 14 (70%) cases were female and 6 (30%) were male in the control group. The age and sex distributions in both groups were similar. Nineteen patients in the morbidly obese group had diabetes mellitus, 15 patients had hypertension, eight patients had hyperlipidemia, and three patients had coronary artery disease. There were no cases with these comorbidities in the control group. The proportions of patients using proton pump inhibitors and consuming alcohol and cigarettes were similar in both groups.

The TRPV1 staining levels of each cell type were determined using the IRS. TRPV1 Levels in fundus, antrum, and duodenum tissues of the morbidly obese patients were similar to those of the control group (Tables 1-3, Figure 1). However, when the staining of the cells was compared with other tissue sites in terms of staining properties, the levels of TRPV1 in antrum and fundus cells in the stomach were higher than those in duodenal cells. Both the intensity and prevalence of TRPV1 were higher in parietal and chief cells in the fundus, foveolar and mucous cells in the antrum, and absorbent cells in the duodenum. Compared to other cells in the stomach, the type of cell with the least TRPV1 staining was the foveolar cells in the fundus.

Evaluation with anti-TRPV1 antibody was performed separately according to cell types in the fundus, antrum, and duodenum tissues. The parietal, chief, and foveolar cells in the fundus; mucous cells in the antrum; and foveolar, mucous, goblet and absorbent cells in the duodenum of the cases were evaluated separately in terms of staining intensity and staining percentages with TRPV1. Staining density was evaluated on a 4-stage (0: negative, 1: weak, 2: moderate, and 3: strong staining intensity) immunoreactivity scale. The staining area was also graded as a percentage scale (0: no stained area; 1: below 25%; 2: between 25%-49%; 3: between 50%-74%; and 4: above 75%). Median staining was approximately 80% in the whole study group; therefore, 80% and below was considered limited staining, and 80% and above was considered widespread staining. The immunoreactivity score (IRS) was calculated as the staining scale (0-3) times the percentage scale (0-4) and was included in the analysis.

Nothing. I was still in full tantrum. So then she lay down beside me on the floor, and began kicking and screaming, I want a new car, I want a new house, I want some jewelry10, I want… Shocked, I stood up.

The relationship between the gastric emptying rate and obesity has been discussed in many studies. Several peptides and hormones that regulate GIT motility and digestion provide the balance of hunger and satiety in the hypothalamus with neuronal feedback[33,34]. In general, it has been shown that the rate of gastric emptying is high in obese people, leading to inadequate negative feedback[35,36]. Previous studies have shown that activation of neuronal TRPV1 with capsaicin decreases motility and delays gastric emptying, especially in the upper GIT[37,38]. We postulate that capsaicin-induced TRPV1 can suppress appetite in this way, and this is one of the possible mechanisms of action against obesity. Another possible mechanism may be the faster release of hormones and peptides that reduce gastric motility and cause anorexigenic effects due to faster digestion of nutrients, especially after the activation of TRPV1 in cells involved in digestion, such as fundus chief cells and parietal cells. In one study, TRPV1 was shown to increase somatostatin and gastrin levels, which help digestion in antral glands and reduce gastroduodenal motility[29]. Finally, it has been shown that leptin, which is produced by adipocytes and produces a feeling of satiety in general, is also synthesized from mucosal chief cells in the gastric fundus, where we have shown intense TRPV1 staining[39]. Therefore, TRPV1 activation may increase leptin release from mucosal chief cells; this hypothesis needs to be investigated further in different experimental setups.

DISCUSSION

49 When the day came on which the sentence was to be executed, it was the last day of the six years50 in which she must not speak or laugh, and now she had freed her dear brothers from the power of the enchantment

One day the girl said to him that now it was close on the time when he must become a fish again--the troll would soon call him home, and he would have to go, but before that he must put on the shape of the fish, otherwise he could not pass through the sea alive

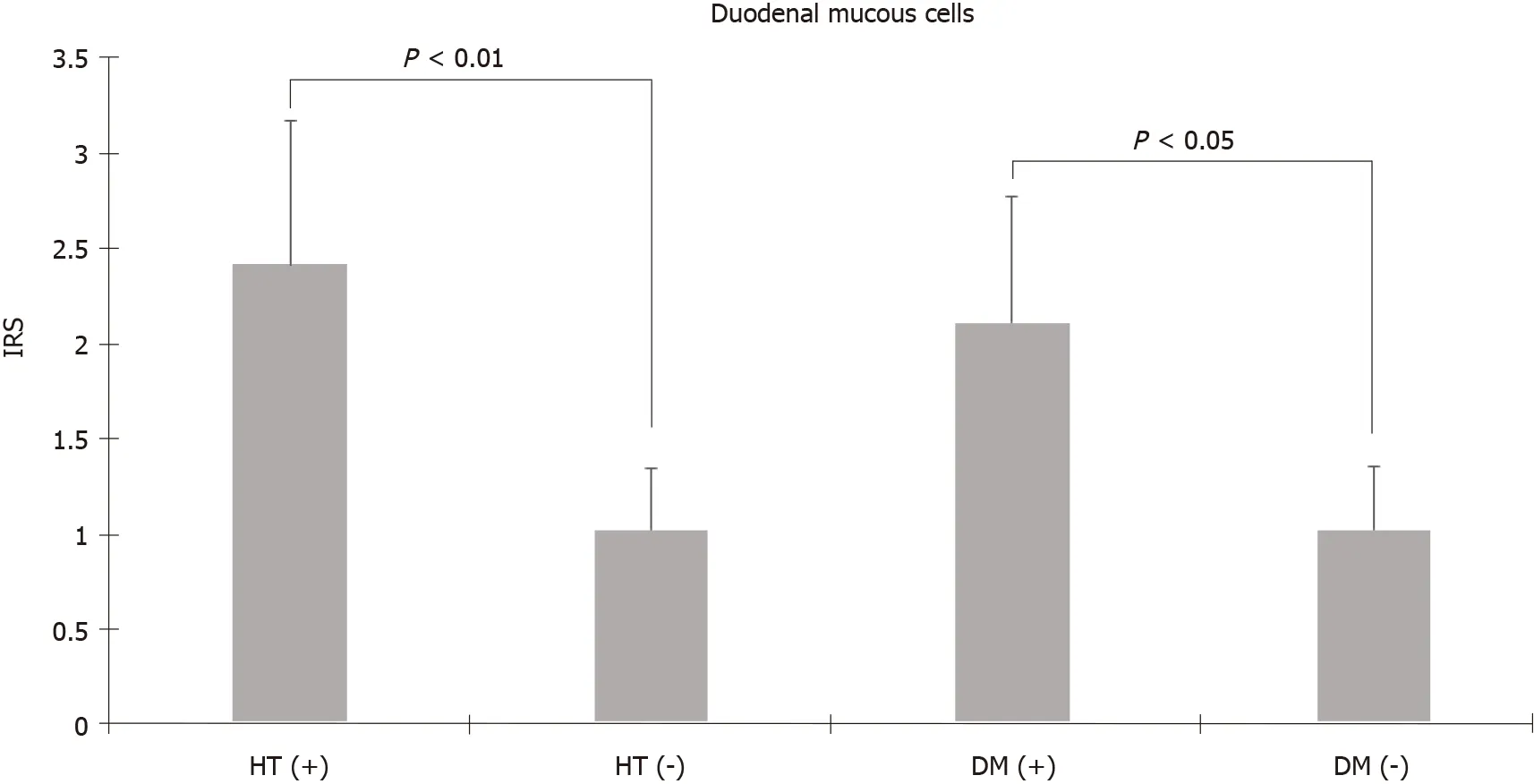

Animal studies have reported that TRPV1 is expressed in gastric mucosa and can participate in mucosal protection by increasing cell proliferation and blood flow[26,27]. In addition, an animal study suggested that capsaicin has gastroprotective effects against gastric antral ulcers through capsaicin-sensitive afferent nerves[25,27]. Our study showed the presence of TRPV1 on mucous and foveolar cells that have mucosal protective effects. In particular, TRPV1 Levels in mucous and foveolar cells in the antrum were higher than those in foveolar cells in the fundus and mucous cells in the duodenum. The high incidence of TRPV1 in cells in the antrum where ulcers are mostly localized supports that capsaicin shows a protective effect against ulcers through both neuronal and nonneuronal cells. It has been shown that the risk of peptic ulcers and bleeding as well as mortality increases when comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, which are prevalent in advanced ages, are present[32]. The increased levels of TRPV1 in antrum and duodenum mucous cells in patients aged 45 years and older and in patients with diabetes and hypertension suggest that TRPV1 activation in gastroduodenal mucosa may be gastroprotective, especially in these groups.

The cases were evaluated in terms of staining intensity according to age (< 45 years and ≥ 45 years), sex (male and female), diabetes mellitus and hypertension, smoking, and proton pump inhibitor use. TRPV1 staining of all cells were similar in men and women. In addition, there was no difference in terms of TRPV1 staining of all cells between smokers and non-smokers, proton pump inhibitor users and non-users. Staining with TRPV1 in fundus chief cells and antrum and duodenum mucous cells was higher in patients aged 45 years and older than in patients under 45 years (3.03 ± 0.42, 4.37 ± 0.76, 2.28 ± 0.551.9 ± 0.46, 1.58 ± 0.44, 0.37 ± 0.18,= 0.03,< 0.01,< 0.01, respectively, Mann-Whitneytest). The mean staining levels of TRPV1 in duodenal mucous cells in patients with diabetes and hypertension were higher than those in patients without diabetes and hypertension (diabetes: 2.11 ± 0.671.02 ± 0.34,= 0.04; hypertension: 2.42 ± 0.751.02 ± 0.33,< 0.01 Mann-Whitneytest) (Figure 3).

It is evident that the effect of TRPV1 on gastroduodenal mucosal tissues is multifaceted. Therefore, it is not easy to pinpoint the exact underlying mechanism of capsaicin’s anorexigenic effectTRPV1. Several animal studies and epidemiological studies have been conducted to explain the potential mechanisms of capsaicin’s anorexigenic effect. TRPV1, mainly found in neurons, has also been shown to be present in rodent adipocytes, skeletal muscle, and the hypothalamus[14-16,19,40,41]. Capsaicin has multisystemic effectswidely distributed TRPV1 expression: it promotes lipolysis, inhibits adipogenesis, and increases the transition from white adipose tissue to thermogenic brown adipose tissue in adipose tissue; in the hypothalamus, it reduces appetite and creates a feeling of satiety; it also increases intestinal blood flow and has close relations with glucose homeostasis by increasing insulin secretion in the pancreas and by increasing glucagon like peptide-1 levels[14,17,18,20,42-44]. In light of this information, capsaicin can positively affect energy balance and obesityTRPV1 in neuronal and nonneuronal cells in the GIT, hypothalamus, and adipose tissue. Although the results support that the effect is mostly TRPV1-mediated, the physiological process and mechanism of action are not yet fully understood. Although some human studies on the dietary intake of capsaicin show negative energy balance and anti-obesity effects[21,22,45,46], there are no studies in the literature in which the mucosal cells in the upper GIT are discussed together, especially in obese individuals.

CONCLUSION

This retrospective case-control study was conducted per the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for this study was obtained from the Akdeniz University Faculty of Medicine Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Date: 07/09/2016; Approval number: 2016/486). All patients and healthy volunteers provided written informed consent for participation in the study.

Jack Zipes finds it interesting that the children never blame their parents for their abandonment. He states that the witch symbolizes the feudal103 system with her greed and treasures. When the children kill her, the story shows the hatred which the peasantry felt for the aristocracy as hoarders and oppressors (Zipes 1979).

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

New agents and methods are sought to prevent and treat obesity, which is a serious public health problem.

Research motivation

It has been reported that capsaicin acting on transient receptor potential vanilloid-1(TRPV1) increases thermogenesis, lipid oxidation and energy expenditure and prevents diet-induced obesity.

Research objectives

This study aimed to compare obese individuals with normal individuals in terms of TRPV1 staining in the gastroduodenal mucosa and to determine the distribution of TRPV1 in gastroduodenal mucosa cells.

Research methods

Total 46 morbidly obese patients and 20 control patients were included. Simultaneous biopsies from the fundus, antrum, and duodenum tissues were obtained from subjects. Evaluation with anti-TRPV1 antibody was performed separately according to cell types in the fundus, antrum, and duodenum tissues using an immunoreactivity score (IRS).

Research results

TRPV1 Levels in fundus, antrum, and duodenum tissues of the morbidly obese patients were similar to those of the control group. When the staining of the cells was compared with other tissue sites in terms of staining properties, the levels of TRPV1 in antrum and fundus cells in the stomach were higher than those in duodenal cells. The highest IRS was observed in fundus parietal cells, foveolar cells in the antrum, and absorptive cells in the duodenum. When the staining levels of the same type of cells in different tissues were compared, cells of the antrum had the highest staining intensity, followed by the fundus and duodenum. In addition, Staining with TRPV1 in fundus chief cells and antrum and duodenum mucous cells was higher in patients aged 45 years and older than in patients under 45 years. The mean staining levels of TRPV1 in duodenal mucous cells in patients with diabetes and hypertension were higher than those in patients without diabetes and hypertension.

Research conclusions

We have demonstrated that the expression of TRPV1 is similar in the gastroduodenal mucosa of morbidly obese patients and control subjects. TRPV1 expression was significantly higher in parietal and chief cells of the fundus and mucous and foveolar cells in the antrum, which affects digestion, mucosal protection, and motility. In addition, the unchanged expression of gastric and duodenal TRPV1 in the obese patient group suggests that drugs targeting TRPV1 may be effective in these patients.

Research perspectives

There is a need for more comprehensive long-term studies that can reveal the pathophysiology of obesity for the prevention and treatment of obesity.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2022年1期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Hepatitis B virus reactivation in rheumatoid arthritis

- Paradoxical role of interleukin-33/suppressor of tumorigenicity 2 in colorectal carcinogenesis: Progress and therapeutic potential

- Changes in rheumatoid arthritis under ultrasound before and after sinomenine injection

- Benefits of multidisciplinary collaborative care team-based nursing services in treating pressure injury wounds in cerebral infarction patients

- Outcomes and complications of open, laparoscopic, and hybrid giant ventral hernia repair

- Surgical resection of intradural extramedullary tumors in the atlantoaxial spine via a posterior approach