Role of endoscopic ultrasound in anticancer therapy:Current evidence and future perspectives

Andre Bratanic,Dorotea Bozic,Antonio Mestrovic,Dinko Martinovic,Marko Kumric,Tina Ticinovic Kurir,Josko Bozic

Andre Bratanic,Dorotea Bozic,Antonio Mestrovic,Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology,University Hospital of Split,Split 21000,Croatia

Dinko Martinovic,Marko Kumric,Tina Ticinovic Kurir,Josko Bozic,Department of Pathophysiology,University of Split School of Medicine,Split 21000,Croatia

Tina Ticinovic Kurir,Department of Endocrinology,University Hospital of Split,Split 21000,Croatia

Abstract The digestive system is one of the most common sites of malignancies in humans.Since gastrointestinal tumors represent a massive global health burden both in terms of morbidity and health care expenditures,scientists continuously develop novel diagnostic and therapeutic methods to ameliorate the detrimental effects of this group of diseases.Apart from the well-established role of the endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) in the diagnostic course of gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary malignancies,we have recently become acquainted with a vast array of its therapeutic possibilities.A multitude of previously established,evidence-based methods that might now be guided by the EUS emerged:Radiofrequency ablation,brachytherapy,fine needle injection,celiac plexus neurolysis,and endoscopic submucosal dissection.In this review we endeavored to provide a comprehensive overview of the role of these methods in different malignancies of the digestive system,primarily in the treatment and symptom control in pancreatic cancer,and additionally in the management of hepatic,gastrointestinal tumors,and pancreatic cysts.

Key Words:Pancreatic cancer;Endoscopic ultrasound;Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle injection;Pancreatic cyst;Gastrointestinal tumor;Portal vein

INTRODUCTION

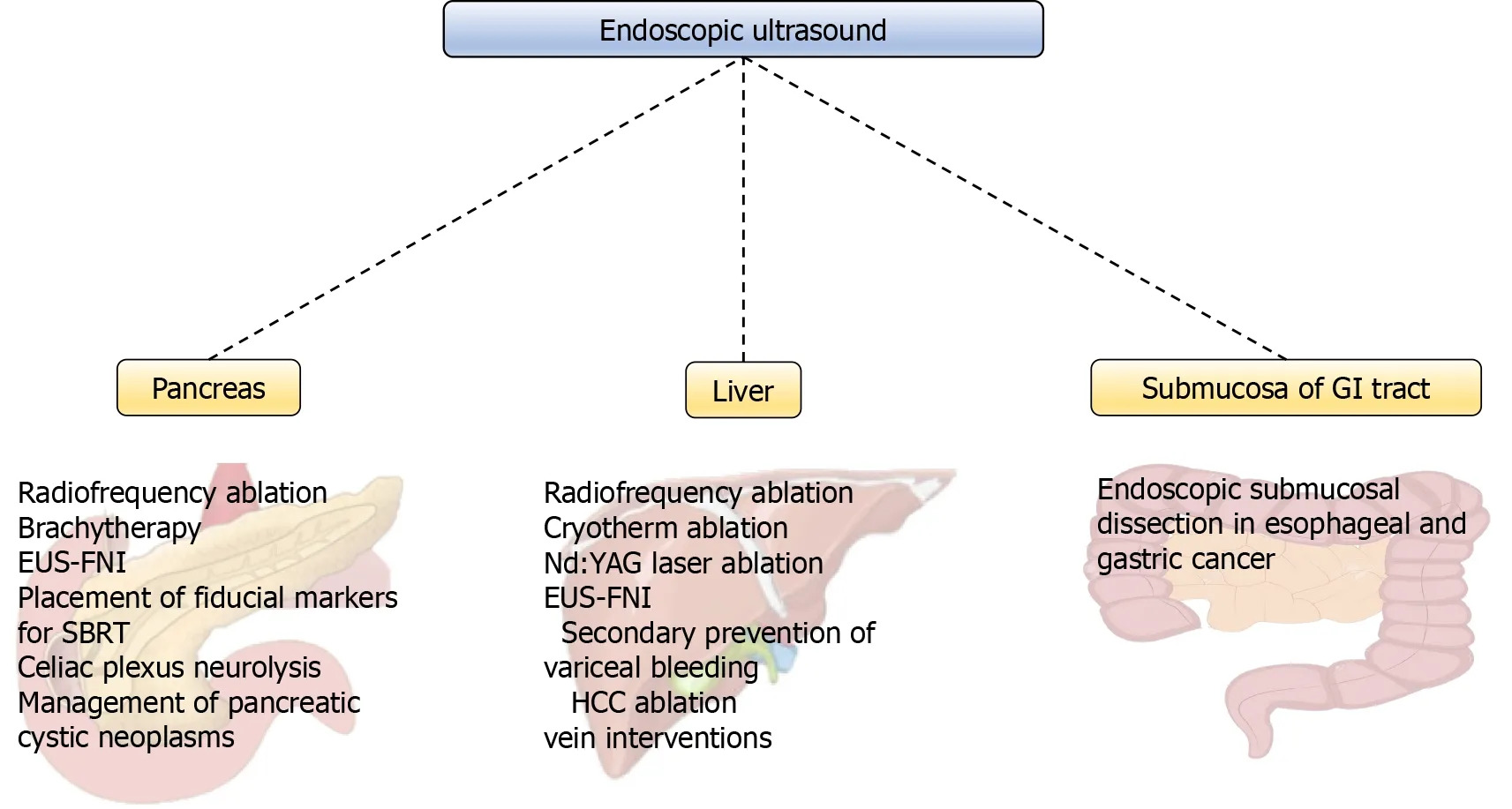

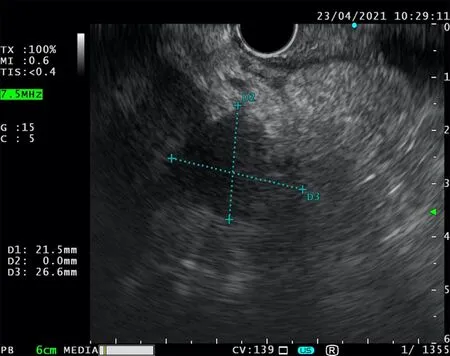

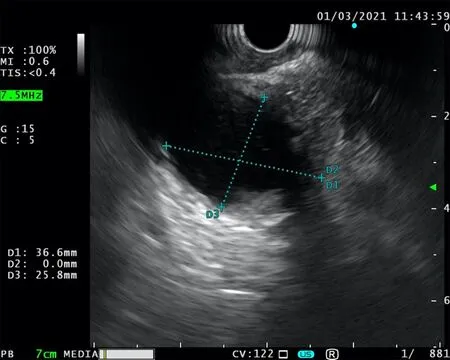

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is one of the principal tools in cancer screening and staging.Apart from its use in the diagnostic course of gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary malignancies,it has an entire range of other therapeutic possibilities (Figure 1).The ability of the EUS to obtain tissue samples using either fine needle aspiration(FNA) or fine needle biopsy makes it a unique method in the screening of pancreatic cystic lesions,as well as in the assessment of regional lymph node involvement in esophageal,gastric,and rectal cancer (Figures 2-4).The EUS is therefore essential in the concurrent pancreatic cancer diagnosis[1].Over the last few years,the implementation of the EUS has expanded from the diagnostic into the therapeutic field.Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle injection (EUS-FNI) of chemotherapeutics,immunotherapy and gene therapy,tissue ablation,stereotactic radiation therapy,brachytherapy and celiac plexus neurolysis have been thoroughly investigated and steadily introduced into the clinical practice[1,2].Multiple studies suggest that some of these methods might be crucial in overcoming the problem of drug distribution to tumorous tissue in patients with pancreatic cancer,whereas other methods could be of aid in pain management of the same population.In this review we endeavored to give a comprehensive overview of the role of the EUS in anticancer therapy:primarily in the treatment and symptom control in pancreatic cancer,and,additionally,in the management of hepatic and gastrointestinal tumors.

Figure 1 Overview of endoscopic ultrasound-guided methods.

Figure 2 Endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration.

Figure 3 Unsuccessful endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration.

THE EUS IN TREATMENT OF PANCREATIC CANCER

As hypovascularity and abundant desmoplasia are landmarks of pancreatic cancer,delivery of chemotherapeutic medications to the tumor-affected area is insufficient[3].Consequently,effects of chemotherapeutics on pancreatic cancer are mitigated,resulting in higher required therapeutic doses which increases the incidence of adverse effects[4].Therefore,several local strategies that could possibly overcome these issues were developed.Among a number of EUS-based therapeutic interventions,radiofrequency ablation (RFA),brachytherapy,EUS-FNI,and EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) emerged as viable strategies for improvement of poor outcomes regarding the pancreatic cancer.

RFA

RFA is an invasive antitumor method which works by generating heat from highfrequency alternating current that induces frictional heating,leading to thermal coagulative necrosis of the target tissue[5].In addition,several authors demonstrated that RFA may trigger immunomodulatory activity,and in this way,further dampening the cancer development[6-9].RFA is already a well-established therapeutic modality in management of other cancers,particularly for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma,and has been included in the latest guidelines for management of hepatocellular carcinoma by a major European organization[10].

Owing to the anatomical positioning of the pancreas,suitable approaches for the inclusion of the RFA in pancreatic cancer are multiple,including open surgery,laparoscopic approach,percutaneous approach,and an EUS-guided approach.Initially,safety and effectiveness of EUS-guided RFA of the pancreatic tissue were evaluated in porcine models[11-14].Although results of the animal studies were promising,clinicians were doubtful,as thermal-induced pancreatitis and thermal injuries of the adjoining structures emerged as adverse effects in the animal studies and in early intraoperative studies[11,15-17].Early on,surgeons observed that detrimental effects of intraoperative RFA could be reduced by using lower temperatures,maintaining a margin from the major adjacent vessels,and by using stepwise approach in bigger,poorly demarcated lesions[18,19].Intraoperative studies have also provided an insight into the effectiveness of the RFA.Multiple studies have demonstrated that intraoperative RFA leads to tumor necrosis and a decrease of tumor volume,as well as reduction in CA 19-9 plasma levels,the main pancreatic cancer marker[16,20-25].Unfortunately,in all of the aforementioned studies,all patients that underwent RFA eventually developed disease progression[16,20-25].Of note,in a small sample (n=25)study by Spiliotiset al[16],authors have shown a significant prolongation in survival in patients treated with both palliative care and RFA in opposition to patients that received palliative care exclusively,an observation that Matsuiet al[25] failed to demonstrate.In addition,Cantoreet al[26] argue that combined multiple-treatment followed by RFA can prolong survival in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer.

Together,these findings paved the way for the investigation of the EUS-guided RFA.In a pilot study by Songet al[27],6 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer underwent EUS-guided RFA.Two out of six patients suffered abdominal pain,whereas other patients reported no adverse,effects implying the safety of the procedure.However,as the purpose of the study was to assess the technical feasibility and safety of the procedure,long-term survival of the patients was not studied.Multiple similar studies were performed following this study,and their results with regard to effectiveness and adverse events were summarized in a recent meta-analysis by Dhaliwalet al[28].Meta-analysis showed that technical success,defined as the successful placement of the needle within the pancreatic lesions with safe margins from the surrounding vital structure,and clinical success,defined as decrease in lesion size and presence of necrosis on CT scan after the procedure,were 100% and 91.5%,respectively.Adverse events were observed in 15% of the patients,with abdominal pain being the most common (10%) and only 2 cases of pancreatitis and 1 perforation in total.Overall,the EUS-guided RFA appears to be safe,but multicenter,randomized control trials are needed in order to clearly define the utility of this method.

EUS-FNI

EUS-FNI is an antitumor agent delivery method in which the EUS serves as a guide for needle placement into target lesions.Aside from injection of various therapeutic agents,EUS-FNI is also suitable for implantation of fiducial markers that enables targeted radiation therapy and for injection of dyes to tattoo the tumor[29,30].The first human clinical trial (phase I) using the EUS-FNI was performed by Changet al[31] in 2000.Authors used EUS-FNI to deliver allogeneic mixed lymphocyte culture(cytoimplant) into the tumor tissue.The median survival of the 8 patients enrolled in the study was 13.2 mo,with 3 partial responses and no adverse events reported.Since then,the largest conducted trial of this sort was a phase III trial in which effects of TNFeradeTMbiologic,in combination with fluorouracil and radiotherapy,were assessed on 304 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer[32].Unfortunately,Hermanet al[32] failed to demonstrate better progression-free survival or overall survival in comparison to controls.Recently Leeet al[33] conducted a phase I trial in which authors combined adenovirus-mediated double-suicide gene therapy with gemcitabine in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer.Nonetheless,despite the fact that the trial proved the safety of the procedure,pioneers of EUS-FNI argued in a recent paper that a lot of hurdles have to be overcome in order to develop a clinically functional EUS-FNI method,especially in terms of oncolytic viruses[34].Among recently conducted trials,we have highlighted the following two:(1)Nishimuraet al[35] injected a double-stranded RNA oligonucleotide that repressed tumor growth in 6 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer and reported no adverse effects,as well as reduction in plasma levels of the target molecule and tumor size reduction;and (2) A prospective study by Levyet al[36] tested the use of EUS-FNI for the guided delivery of gemcitabine,a chemotherapeutic whose role in treatment of pancreatic cancer has been well-established.Authors administered gemcitabine in 36 patients with various stages of pancreatic cancer (II-IV),and no adverse events were reported.Overall survival of the patients was 10.4 mo,and more importantly,20% of patients with stage III unresectable disease were down-staged and underwent an R0 resection.In conclusion,as pancreatic cancer is a systemic disease,it is practically impossible to assume that EUS-FNI will fully replace current therapeutic modalities of pancreatic cancer,but,given the safety and feasibility of the method,as well as expansion of translational medicine,it could emerge as a viable adjuvant method in the future.

Brachytherapy

EUS-guided brachytherapy involves implantation of radioactive seeds directly into or adjacent to the tumor-affected tissue.The target tissue is then exposed to the emission of low-energy gamma,X-rays,or beta particles,leading to localized tissue injury and tumor ablation.The main advantage of brachytherapy is its ability to deliver a markedly higher dose of radiation to the tumor mass in comparison to external beam radiation therapy.In the latter,radiation beams pass through other non-tumorous tissues in reaching the target mass,thus resulting in collateral toxicity and more damage to healthy tissue.Although there is abundant evidence to suggest that brachytherapy can deliver a higher dose of radiation and provide local control as well as palliative benefits,currently no brachytherapy device is approved for the treatment of patients with pancreatic cancer[37-42].There are multiple approaches for implantation of radioactive seeds,one of which is the EUS-guided brachytherapy,and a variety of chemical elements that could be used in this manner (phosphorus-32 (P-32),iodine,gold,iridium,etc.)[43,44].Two pilot trials that tested the potential of EUS-guided brachytherapy in patients with pancreatic cancer had rather disappointing results with no benefits with regard to overall survival rate (27%) and partial response rate (13.6%),respectively[45,46].Nonetheless,authors of one of the trials argued that such results might be due to an insufficient radiation dose to local lesions[47].They performed another study in which they implemented a novel computer-aided treatment-planning system (TPS).Under the support of the new TPS,partial remission rate was 80% and expected median survival time of the 42 patients was 9.0 mo (24 patients were in stage IV).At present,there is an ongoing open-label,single-arm pilot study of EUS-guided brachytherapy with P-32 microparticles in combination with gemcitabine and/or nabpaclitaxel in unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer (OncoPaC-1 study)[48].However,the role of the EUS-guided brachytherapy in pancreatic cancer is yet to be determined.Hopefully,conjunction of brachytherapy and chemotherapeutics will increase the share of patients with pancreatic cancer that convert to resectable and provide us with more durable,local control in comparison to conventional treatments.

EUS-guided celiac plexus neurolysis

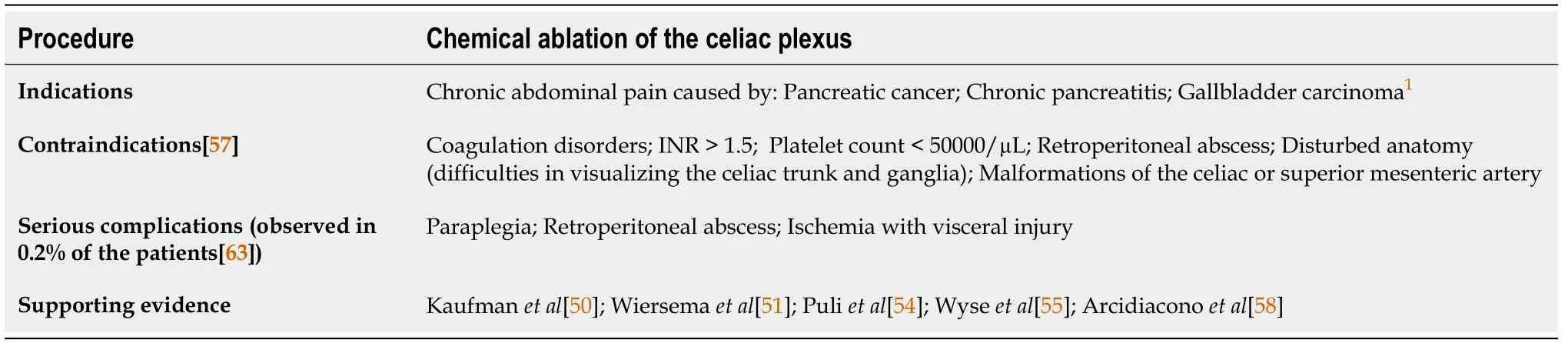

Among a multitude of options,the EUS has also found its place in the palliative treatment of patients with pancreatic cancer.Given the fact that most patients present in the advanced stages of the disease,palliative care is often the primary goal of care.Pain,the most significant and most common complication of pancreatic cancer,has traditionally been managed by nonsteroidal and opioid analgesic,often with numerous side effects,including constipation,sedation,nausea,vomiting,and delirium[49,50].In order to overcome these issues and while trying to improve quality of life,endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis (EUS-CPN) was introduced by Wierseme and Wierseme in 1996 (Table 1)[51].

Table 1 Overview of the endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus neurolysis characteristics

EUS-CPN is a minimally invasive method for the treatment of pain through the chemical ablation of the celiac plexus under the control of the EUS.The current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend EUS-CPN for treatment of severe pancreatic cancer-associated pain in the case of failure of achieving adequate analgesia and/or intolerable adverse effects[52].

The EUS-guided neurolysis is indicated for patients with chronic abdominal pain caused by an upper GI tract malignancy,mostly pancreatic cancer.Patients with unresectable disease whose pain affects their quality of life are considered good candidates for this approach.Furthermore,there are pivotal studies of the EUS-CPN efficacy in patients with gallbladder carcinoma[53].However,besides pancreatic carcinoma,the main indication for EUS-CPN still remains chronic pancreatitis[50,54].

The optimal timing in which the EUS neurolysis should be applied is still unclear.However,in randomized,double-blind,controlled trial,Wyseet al[55] found that early EUS-CPN,performed during the diagnostic EUS,provided better pain management and prevented an increase in morphine consumption than EUS-CPN later in the course of the disease.However,further studies are needed to define the optimal timing for CPN.CPN consists of injecting a neurolytic agent (absolute alcohol or phenol) into the area around the celiac plexus monitored by an echo endoscope with prior administration of a local anesthetic (bupivacaine or lidocaine).Application of the neurolytic agent can be unilateral (just above the celiac trunk) or bilateral (on both sides of the celiac trunk)[56-58].

Several studies have shown pain improvement after CPN[50,51,54,55].In the initial study,pain improvement was achieved at 2,4,8,and 12 wk after CPN in 79%-88%patients[51].Additionally,a Cochrane Review of six studies (358 patients),that showed that the EUS-CPN was superior at 4 and 8 wk compared to drug-based management,with significant drug consumption reduction[5].Whether the application of the EUS-CPN affects survival remains unclear.A study by Fujii-Lauet al[59] indicates that the EUS-guided neurolysis is associated with longer survival than the non-EUS guided approach.However,further studies are needed to assess the potential impact of the neurolysis on survival.In order to improve the efficiency of pain treatment,the following EUS-CPN modifications have been presented:EUSguided direct celiac ganglia neurolysis (EUS-CGN);and EUS-guided broad plexus neurolysis[60-62].In a randomized study by Doiet al[60],authors indicated better pain improvement in CGN over CPN.Levyet al[61] have successfully demonstrated the modification of the neurolysis of the celiac plexus in the form of direct injection of the agent into the celiac ganglion,requiring prior visualization of the ganglia itself.Sakamotoet al[62] in 2010 described the injection of a neurolytic agent in the area around the origin of the superior mesenteric artery,introducing a method of broad plexus neurolysis,which demonstrated better pain relief compared to the CPN.

A recent review of 20 studies comprising 1142 patients,revealed that complications of EUS-CPN occurred in 21% of 661 EUS-guided CPN interventions[63].The most frequent complications included diarrhea,transient pain exacerbation,and hypotension.Most of the complications seem to be a consequence of a sympatholytic reaction and are self-limited (<48 h).However,in 0.2% of cases,major complications were observed,including paraplegia,retroperitoneal abscess,and ischemia with visceral injury[63].

Given the unequivocal beneficial effects of EUS-CPN in the palliative care of the patients with advance pancreatic cancer,we can expect further increase of its usage in routine clinical practice.

EUS IN PANCREATIC CYSTIC NEOPLASMS

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) represent a heterogeneous group of pancreatic cysts with significant differences in their pathological and clinical features,the most important one being the difference in malignant potential among subtypes.These differences are important as they determine the approach for both the treatment and the surveillance of PCN[64-66].A prevalence of all PCN varies from 2%-45% in general population)[67-70],with constant increase in the PCN detection rate.The explanation for the observed increase lies in the improved modalities of non-invasive (computed tomography (CT) scan,magnetic resonance imaging- cholangiopancreatography (MRIMRCP)) and minimally invasive (endoscopic ultrasound-fine needle aspiration (EUSFNA)) imaging methods,and their broader use in preventive check-ups,as well as an awareness of true nature of PCN and the necessity for their close follow-up.According to different studies,abdominal ultrasonography detects PCN in 0.21% of individuals[71],CT in 2.6%[72],and MRI-MRCP in 2.4% to 49.1% of tested individuals[65,72-74].The management of PCN may be quite challenging,with identification of specific PCN type being a crucial step since malignant potential varies significantly between different types of PCN.Timely and correct management of PCN is vital,as it may prevent progression to pancreatic cancer and decrease the need for lifelong follow-up[71].

Due to the challenges in differentiation between the various types of PCN and its implications on therapeutic approach,guidelines on the management of PCN were proposed by expert groups,most notably by the Association of Pancreatology,the American Gastroenterological Association,and by the European Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas[65,66,73,75].Various approaches,including surgical resection,endoscopic techniques,and surveillance,are covered in all of the abovenoted guidelines.Surgical resection is the golden standard for management of premalignant and malignant cystic lesions.Indications for resection depend on the presence of symptoms,probability of malignancy,location of the lesion,and surgical risk of the patient.On the other hand,surgery carries a considerable risk,with perioperative complication rates from 20% to 40%,and mortality rates up to 2%[76-79].Therefore,endoscopic techniques represent an important alternative to surgery,especially in patients with significant comorbidities or in cases of indeterminate cystic lesions.

The main advantage of the EUS in this setting is the fact that EUS-guided pancreatic cyst ablation using ethanol and/or paclitaxel enables organ preservation,leaving endocrine and exocrine function intact[80-83].However,there is concern about the use of ethanol,as the rate of reported complications was as high as 2%-10%[84].Another disadvantage of this method is the inability to obtain a sample for histopathological analysis.The long-term effects of ablation and prevention of malignant alteration are yet to be evaluated in future studies[84-87].The current diagnostic workup of PCN includes CT or MRI with the addition of MRCP and EUS when appropriate[64-67,88].EUS is indicated in addition to other imaging modalities if there are worrisome clinical or radiological features present (nodules,dilated pancreatic duct,thickened wall),or if there is a need for obtaining the cystic fluid for cytological and/or biochemical analysis.

The reported accuracy of EUS imaging for differentiating mucinous from nonmucinous PCN is relatively low (48%-94%),with sensitivity of 36%-91%,and specificity of 45%-81%[89-93].Cytopathological analysis of cystic fluid may reveal dysplasia or clear malignancy.Although cytology is highly specific (83%-100%),it is relatively insensitive (27%-48%),resulting in relatively low diagnostic accuracy of this procedure (8%-59%)[89-92,94].However,sensitivity could be increased by an additional puncture of the cystic wall.Additional biochemical markers,including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA),which has been proved to be useful in distinction between mucinous and non-mucinous PCN,and amylase,which strongly suggests a connection between the cyst and the pancreatic ductal system,may also be obtained from cystic fluid[95,96].Combination of multiple EUS-guided methods,such as EUS morphology,cytology,and cyst fluid CEA,provide us with greater accuracy in detecting malignant PCN than any of the methods individually[97,98].Recently,DNA testing of pancreatic cyst fluid emerged as a promising additional tool for the differentiation between mucinous and non-mucinous PCN,between mucinous PCN subtypes,and between premalignant PCN and advanced neoplasia[99].

According to the latest recommendations,surgically fit patients with asymptomatic cysts that are presumed to be premalignant (intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) or mucinous cystic neoplasms(MCN)),but which possess no concerning features,should be monitored,preferably using MRI-MRCP or EUS if MRCP is not available[100,101].In cases in which any of the worrisome features emerges,the EUS-FNA should be used in the cyst follow-up.For both IPMN and MCN,surveillance should continue as long as the patient is fit for surgery[102].On the other hand,current guidelines do not address the need for surveillance in asymptomatic patients with serous cystic neoplasms (SCN),since malignant progre-ssion of SCN is very rare[102-104].

EUS-GUIDED PORTAL VEIN INTERVENTIONS

The portal vein (PV) can be accessedviatrans-gastric or trans-duodenal access under the EUS guidance using an 18G-25G needle with low risk of complications.Multiple studies have demonstrated that EUS is successful in sampling of the PV to reveal circulating tumor cells,as well as obtaining the portal vein thrombus specimen[105],which has an utmost significance in the staging of hepatocellular liver cancer (HCC)[106-108].The diagnostic yield of the EUS is confirmed by the reported cases of HCC detection using the EUS-FNA of radiologically suspected malignant thrombi without an evident liver mass[108,109].

As a significant step forward,Parket al[110] have even demonstrated the technical feasibility of the EUS guided transhepatic PV stenting in porcine models,without any immediate or late complications[110].However,patients who undergo PV stenting due to malignant thrombosis or stenosis may bear certain procedural risk factors,such as coagulopathy and risk of rapid clinical deterioration if biliary leak or bacteremia occurs.

The EUS-guided PV injection of chemotherapy (EPIC) is another novel therapeutic possibility with a few significant advantages in comparison to the current methods[106].EPIC uses drug eluting microbeads that eventually lodges in hepatic sinusoids and results in the prolonged hepatic drug exposure[111].Studies suggest that EPIC achieves appropriate intrahepatic drug levels,while simultaneously bypassing the systemic side effects and avoiding the ischemic bile duct injury that occurs during the transarterial approach[106].Faigelet al[111] compared the EPIC administration of irinotecan loaded liquid chromatography beads with the systemic unloaded irinotecan application in animal models and revealed EPIC-associated higher irinotecan intrahepatic concentration,as well as lower plasma,bone marrow,and skeletal muscle drug concentrations.Two years later,the same group confirmed their findings on a greater number of animal models using irinotecan,doxorubicin,and albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticles[112].

Preoperative selective embolization of the PV branch that feeds the tumor-affected liver lobe has been utilized in clinical practice since 1986 using the percutaneous transhepatic approach[106,113].Embolization leads to the atrophy of the involved liver segment and hypertrophy of the remnant liver parenchyma,thus preventing the postoperative liver failure[113].Recently,Parket al[113] used nine porcine models to successfully prove the efficacy and safety of the EUS guided embolization of the PV using coil and cyanoacrylate.Furthermore,Mattheset al[114] demonstrated efficient selective PV embolization using ethylene-vinyl alcohol copolymer,known as EVAL(Enteryx),in an animal model.Unfortunately,to our knowledge,studies including PV interventions in anticancer treatment have been so far limited to animal models.Still,exciting advances in the field are revealed,and prospective studies involving humans are eagerly awaited.

ROLE OF THE EUS IN LIVER TUMOR MANAGEMENT

EUS-guided tumor ablation is a safe and effective treatment modality for tumor lesions of the caudate and left liver lobe.Multiple studies have successfully demonstrated the benefits of ethanol administrationviaEUS-FNI in the treatment of both HCC and liver metastases[115].Carraraet al[116] described the EUS guided transgastric bipolar hybrid cryotherm ablation on a porcine model without complications.Varadarajuluet al[117] reported RFA in animal models with effective coagulation necrosis of large areas and without damage to the surrounding liver parenchyma.Multiple studies have also demonstrated success of the EUS-guided neodymiumdoped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser ablation in patients with HCC and colorectal cancer metastases[118,119].In addition,several other methods,including injection of sclerosants and chemotherapeutics,represent viable future therapeutic options[115].

In the management of the HCC-related complications,one of the most common and disastrous is the variceal bleeding incident.With respect to secondary prevention of this complication in patients with inoperable HCC,Tanget al[120] used EUS guided cyanoacrilate injection,which led to reduced rebleeding rates,as well as improved variceal bleeding free survival.

ROLE OF EUS IN ENDOSCOPIC SUBMUCOSAL DISSECTION

The development of gastrointestinal endoscopic tissue resection techniques demands precise diagnostic tools in the preoperative evaluation.Accurate information about the depth of tumor invasion of the gastrointestinal wall and the nodal involvement are necessary for determining the appropriate intervention.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD),the newest and most invasive method,has become standard of care of precancerous and some early cancer lesions in gastrointestinal tract,allowing curative resection of the lesions[121].Depending on the proximity of the GI tract wall during the procedure,the EUS enables clear image of the lesion depth and vital surrounding structures,especially of the lymph nodes[121].

Endoscopic resection is indicated in early esophageal cancer with minimal or no lymph node invasion[122].According to the latest guidelines for the treatment of esophageal cancer of the Japan Esophageal Society,the absolute indication for endoscopic resection is defined as flat lesion (Paris 0-II),with m1 (intraepithelial) - m2(invading lamina propria) invasion,and circumferential extent of ≤ 2/3[123].A systematic review and meta-analysis has demonstrated that sensitivity and specificity for T1a staging were 85% and 87%,respectively,and 86% for both sensitivity and specificity for T1b staging[124].However,the ability of the EUS to predict endoscopic resectability by discrimination between T1 and T2 lesions is still intensively studied.Available data suggests that 15%-25% of cases are under-staged compared with endoscopic mucosal resection staging,while about 4%-12% of cases are over-staged[125,126].

Conventional EUS has limited accuracy in the detection of submucosal invasion in early esophageal cancer[127,128].It remains questionable whether the EUS should be routinely performed prior to ESD of esophageal superficial lesions.European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) suggests that EUS should be considered in esophageal superficial carcinomas with suspicious features for submucosal invasion or lymph node metastasis[122].

Esophageal submucosal tumors are becoming more common indication for ESD.EUS allows for the evaluation of size,echo pattern,layer of origin,and eventual surrounding nodal involvement[121,129].The biggest setback in EUS evaluation is still interobserver variation.Notwithstanding,endoscopic ultrasonography has become the most valuable tool in diagnostics of esophageal submucosal tumors[129].

The role of EUS in establishing the feasibility of endoscopic resection of superficial gastric lesions is still controversial.ESD is indicated as the treatment of choice for most gastric superficial neoplastic lesions,including low- or high-grade non-invasive neoplasia and adenocarcinoma with no evidence of deep submucosal invasion[130-133].Although EUS is considered a reliable method for locoregional staging,endoscopic evaluation is still favored over EUS for predicting endoscopic resectability[134].We should also highlight different approaches in the use of EUS before intervention.Although favored in the prior planning of endoscopic resection in Western countries,in the Eastern countries (in which the incidence of gastric cancer is notably higher),it is not considered necessary to perform EUS in the preoperative evaluation prior to the planned intervention[131,135,136].

Since ESD has been achieving similar results compared with surgery in treatment of gastric submucosal tumors (<50 mm in size),the role of the EUS in preoperative management has recently evolved[137].Today,it is the main tool in preoperative assessment,including evaluation of size,layer of origin,and echo pattern.Furthermore,the use of EUS has extended to marking the lesion with EUS-assisted injection into the muscularis propria,providing a deeper safety cushion for submucosal dissection procedure[138].

A randomized study by Fernandez-Esparrachet al[139] concluded that EUS and MRI have similar accuracy in T and N staging for rectal cancer.The ESGE recommends using one of these methods for staging of rectal cancer,but not for colon cancer[122].However,the role of EUS and MRI for superficial lesions has been undefined.

A prospective study comparing high frequency EUSvsmagnifying chromoendoscopy in early colorectal neoplasia showed that high frequency EUS was superior to chromoendoscopy in determining the depth of invasion,showing an accuracy of 93%vs59%[140].Nevertheless,endoscopic resection will probably remain the best staging tool for superficial rectal lesions,and if the endoscopist feels the lesion is endoscopically resectable,it will probably not require preoperative EUS[122].On the other hand,according to the ESGE recommendations,the use of EUS or MRI should be considered for rectal lesions with endoscopic features suspected for submucosal invasion,since the finding of suspicious lymph nodes could be an indication for neoadjuvant treatment[122].

To summarize,the role of EUS in ESD is still evolving.The main goal of the endoscopic ultrasonography remains to evaluate a potential submucosal invasion and locoregional staging of the disease.Future research on the role of EUS in ESD should be concentrated in reduction of interobserver variations and alleviating possible complications.

CONCLUSION

Even though recent technological advancements in endoscopic approaches led to an improvement of outcomes of tumors in the abdominal cavity,as indicated by reduced mortality,morbidity,and palliative care,we are still far from having an optimal treatment,particularly for pancreatic cancer.Nonetheless,the novel EUS-guided approaches (RFA,brachytherapy,FNI,etc.) for pancreatic cancer might be crucial in overcoming the problem of drug distribution to tumorous tissue and reducing the required therapeutic doses and incidence of adverse effects.In addition,alleviating extreme pain that many patients with pancreatic cancer endure seems to be achievable through celiac plexus neurolysis.Furthermore,EUS is already a part of the algorithm in management of PCN,where EUS-FNA is the method of choice in case of appearance of certain alarming features of cysts.

The utility of EUS in PV interventions is most prominent in relation to the staging of HCC.The role of EUS in ESD with respect to management of precancerous and some early cancer lesions in GI tract,as well as EUS-guided treatment of various hepatic cancers,is yet to be determined,as current data is insufficient to recommend these techniques as standards of care.

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology2021年12期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology2021年12期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology的其它文章

- Management of obstructive colon cancer:Current status,obstacles,and future directions

- Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for gastrointestinal cancer

- Gender differences in the relationship between alcohol consumption and gastric cancer risk are uncertain and not well-delineated

- Pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms:Current diagnosis and management

- Combined treatments in hepatocellular carcinoma:Time to put them in the guidelines?

- Unique situation of hepatocellular carcinoma in Egypt:A review of epidemiology and control measures