Effects of L-arginine on preeclampsia risks and maternal and neonatal outcomes:A systematic review and meta-analysis

Shonitha Sagadevan, Oorvashree Sri Hari, Mohamed Jahangir Sirajudeen, Gopi Ramalingam, Roopa Satyanarayan Basutkar

Department of Pharmacy Practice, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Ooty, The Nilgiris, Tamil Nadu, India

ABSTRACT

Objective: To summarize whether the supplementation of L-arginine in pregnant women helps in management of preeclampsia and its impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Methods: Studies conducted from the past 17 years (1999 to 2016).were referred from database like Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Scopus, Google Scholar and PubMed. Out of 134 studies, 7 studies were included. L-arginine versus placebo was considered for quantitative analysis. Modified Cochrane data extraction form was used to collect the data. The risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane’s risk of bias assessment tool in RevMan 5.4 and the summary of findings was determined using GradePro software.

Results: L-arginine showed a significant reduction of preeclampsia[odds ratio (OR) 0.38; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25, 0.58)].There was a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure [mean difference (MD) -2.47; 95% CI -4.53, -0.42] and diastolic blood pressure (MD -0.97; 95% CI -3.83, 1.89). The effects of L-arginine on secondary outcomes like maternal gestational age, latency, neonatal weight, and appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, respiration (APGAR)score at 1st and 5th minute were not statistically significant.

Conclusions: L-arginine supplementation is effective in lowering systolic and diastolic blood pressure of preeclamptic patients.However, it has no noticeable effects on maternal and neonatal outcomes.

KEYWORDS: L-arginine; Amino acid supplementation;Preeclampsia; Pregnancy; Arginine supplementation

1. Introduction

Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia are common disorders during pregnancy, with most of the cases developing at or near term. The development of mild hypertension or preeclampsia is the leading cause of maternal and neonatal morbidities[1]. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy account for nearly 18% of all maternal deaths worldwide, with an estimated 77 000 deaths per year[2].Women with diagnosed gestational hypertension-preeclampsia require close evaluation of maternal and foetal conditions for the duration of pregnancy, and those with severe disease should be managed in-hospital[3].

In pre-eclampsia, the enzymatic antioxidant defense mechanism fails, and tissues are injured[4]. Arginine is an essential amino acid,synthesized by endothelial cells. The most active form of arginine is its L-form[5]. The primary site of L-arginine synthesis is in the proximal tubules of the kidney, where L-citrulline is synthesized and released by epithelial cells of the small intestine, which is extracted from the blood, converted to L-arginine, and then released into the systemic circulation. Thus, L-citrulline, the by-product of nitric oxide synthesis from L-arginine, is recycled back to L-arginine incorporating one nitrogen. This modified urea cycle has two functions, a secretory role to regenerate L-arginine for nitric oxide(NO) synthesis and an excretory role to eliminate excess nitrogen created by the cell’s metabolism.

Arginine is commonly used for the treatment of diseases and as a dietary tonic. L-arginine, a substrate of NO, helps in regulating blood pressure by the mechanism of vasodilation[6]. Animal studies show that the L-arginine-NO system is generally regulated at a high rate during pregnancy[7,8], and hypertension, proteinuria, foetal growth retardation, and glomerular damage are induced by NO synthesis inhibition. However, L-arginine supplementation is said to reverse this phenomenon. In humans, administration of L-arginine decreases blood pressure in pregnancy by improving the uterine placental circulation[9,10] and the occurrence of preeclampsia was majorly due to the oxidative stress[11-14]. Therefore, L-arginine might emerge as a new therapeutic option in the treatment and prevention of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy.

The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review of literatures and meta-analysis to assess the effect of L-arginine supplementation in prevention and treatment of preeclampsia. The secondary objective was to evaluate the effect on maternal and neonatal complications and outcomes.

2. Materials and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was reported as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The review protocol was registered prospectively with PROSPERO [Registration number:CRD42021224620].

2.1. Electronic searches

Electronic search was conducted with Title/Abstract and MeSH terms using keywords like “L-arginine, amino acid supplementation,preeclampsia, pregnancy, arginine supplementation, randomized controlled trials”. The search for the relevant studies was conducted by the authors for the period between 1999 to 2016. Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Scopus, Google Scholar and PubMed were the databases used for search. All studies were found to be relevant and were considered and cross indexing was done to scrutinize them. Respective authors were contacted for additional details in case of missing or insufficient data. The studies published in English language were only considered.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Four reviewers (GR, MJS, OSH and SS) conducted the electronic search and gathered full text copies of relevant studies. The obtained literatures were imported to Rayyan via Zotero, based. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were checked. Disagreements were resolved by a fifth review author RSB.

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review and meta-analysis were studies conducted on patients who were 18 years or above.Confirmed singleton pregnancy on or before 24 weeks of gestation;pregnant women who were already on routine medications like labetalol, folic acid, iron, and vitamin supplements, and patients who developed preeclampsia and eclampsia but were previously normotensive, were also included. The studies that included the patients who had a history of hepatic and renal abnormality, known peptic ulcer, esophagitis, gastritis, or hiatal hernia were excluded.Patients with the history of high-risk pregnancy including abruption placenta, gestational hypertension, coagulation disorders, history of drug abuse, auto immune diseases, previous history of depression or anxiety, use of any anti-depressants and other mental disorders,previous stillborn foetus were the other exclusion factors that were considered in this review.

2.3. Types of interventions and control

L-arginine supplementation irrespective of dose, duration,commencement time, type of supplementation either oral or as injectables were included. Studies that used L-arginine alone or in combination with supplementation of ferrous sulphate, folic acid, calcium, and other forms of vitamins were also considered.The groups were considered as the intervention and placebo groups. Both the groups were treated in a similar manner. We assessed the following comparisons: a) L-arginine vs. placebo; b)L-arginine+vitamin supplements vs. placebo.

2.4. Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome measures were preeclampsia as per the definition defined by trial list, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure.Secondary outcome measures included maternal outcomes like gestational age and latency. Neonatal outcomes included birth weight and APGAR score at 1st and 5th minute.

2.5. Critical appraisal of included studies

Critical appraisal was performed to measure the transparency of research and to determine the standard for all the included studies.This was done using Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP)checklist which comprises three sections. The included articles should answer the questions under each of these three sections. The three sections are as follows: 1) Are the results of the study valid?(Section A); 2) What are the results? (Section B); 3) Will the results help locally? (Section C).

2.6. Data collection

Four authors (GR, MJS, OSH and SS) extracted the characteristics and interventions of the included trials independently. The modified Cochrane data extraction form was used for extracting and managing data. The design, aim of study, objectives, publication year, study population, total number of study participants randomized, informed consent, baseline imbalances, primary and secondary outcomes,inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention and control, duration of study, risk and bias assessment, and conflicts of interest were taken into consideration for designing the data collection form. The extracted data were cross-checked by RSB. In case of any queries regarding missing data, the respective study investigators were contacted for clarification.

2.7. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

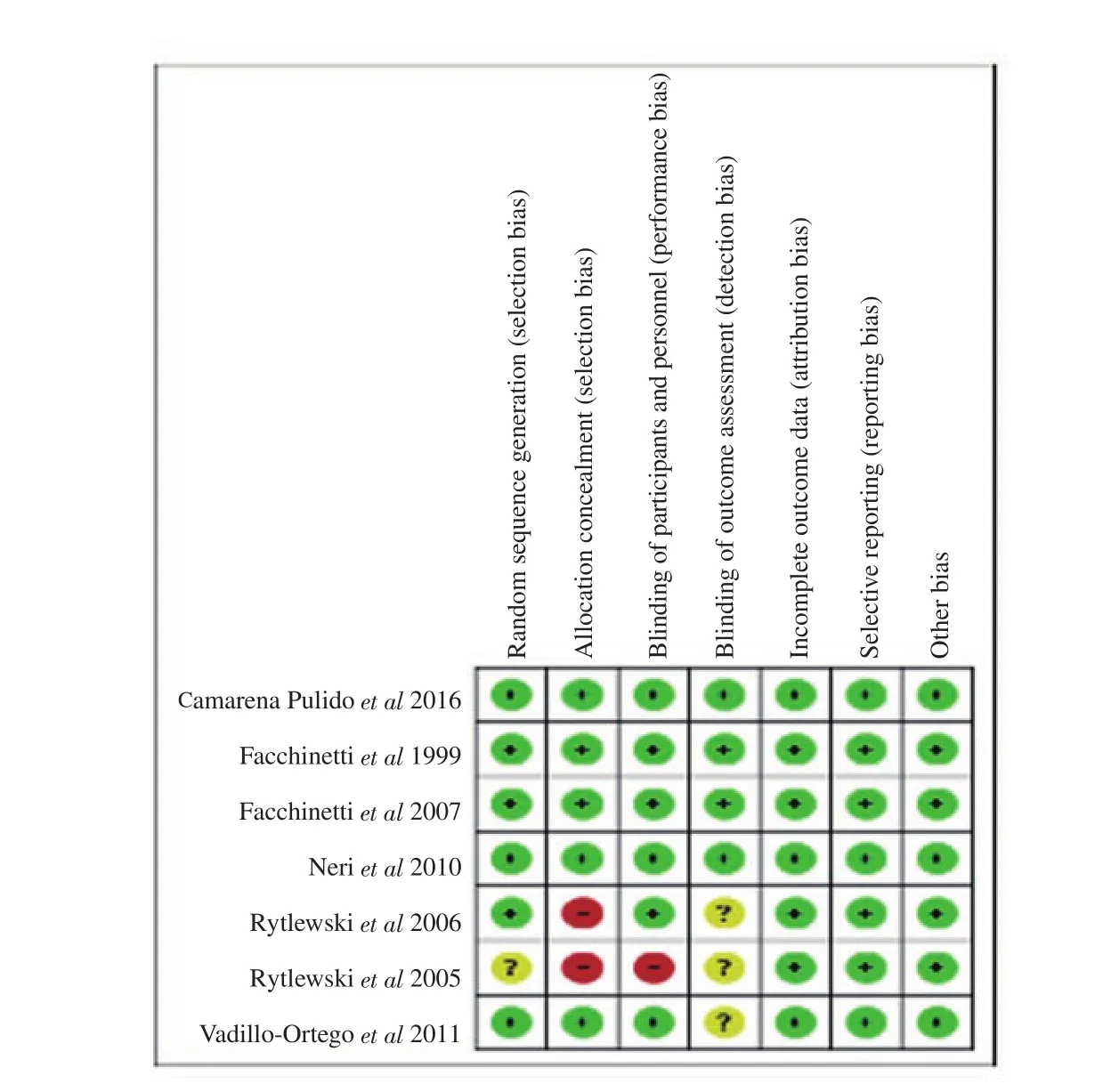

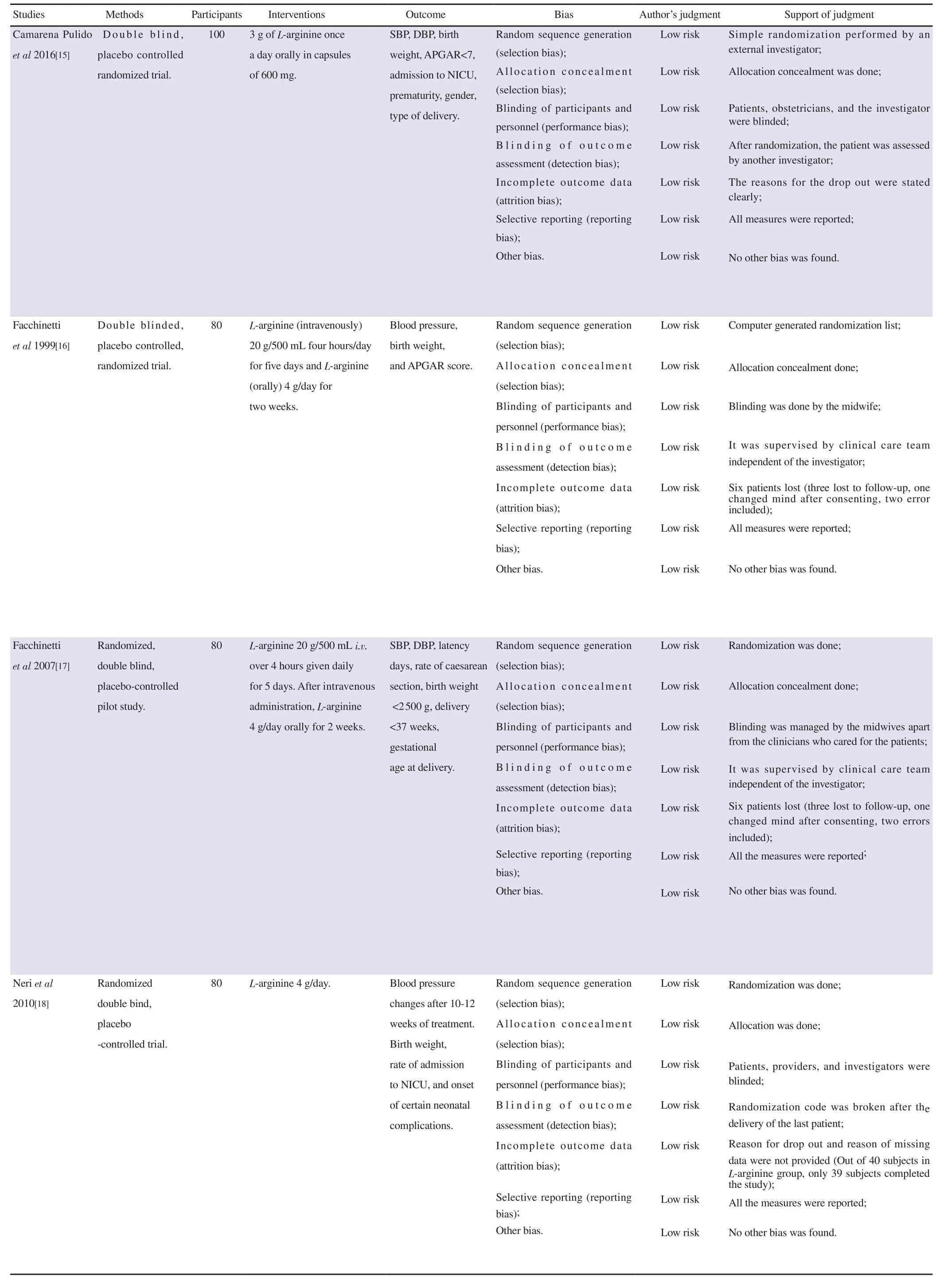

The risk of bias was performed by four independent authors(GR, MJS, OSH and SS). All discrepancies were cross-verified and reviewed by author RSB. Risk of bias was evaluated using Review Manager 5.4. It was evaluated based on selection, allocation concealment, blinding, attrition, and selective reporting. We had categorized our judgments as ‘low’, ‘high’ and ‘unclear’ risk. The included studies were highly varied in their methodological qualities.In Rytlewskii et al study, there was a high risk of selection bias and performance bias as the method of allocation was not concealed and blinding of the study was not done. No other potential sources of bias were identified from other included studies.

2.8. Assessment of evidence using GRADE approach

Grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) approach was used for grading of the outcomes like the effect magnitude of interventions. The certainty of the extracted evidence was categorized into high, moderate, low, very low for a maximum of 8 outcomes. The key information on the outcomes was imported into the summary of findings table.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed based on the recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews. The effect of L-arginine for the prevention of preeclampsia among the pregnant women was the primary outcome to be measured. Quantitative analysis was performed for the primary outcomes of all included studies. For secondary outcomes, the maternal parameters such as latency of pregnancy, gestation age were included. Neonatal parameters such as APGAR score, birth weight were also measured.The mean and standard deviation data of the studies were extracted and computed into Review Manager 5.4 to obtain the mean difference (MD), after which a forest plot was generated. When heterogeneity (I) is less than 50%, fixed model was used, and random effects model was used when Iis between 50% to 90% as it represents substantial heterogeneity between the studies.

3. Results

3.1. Search results

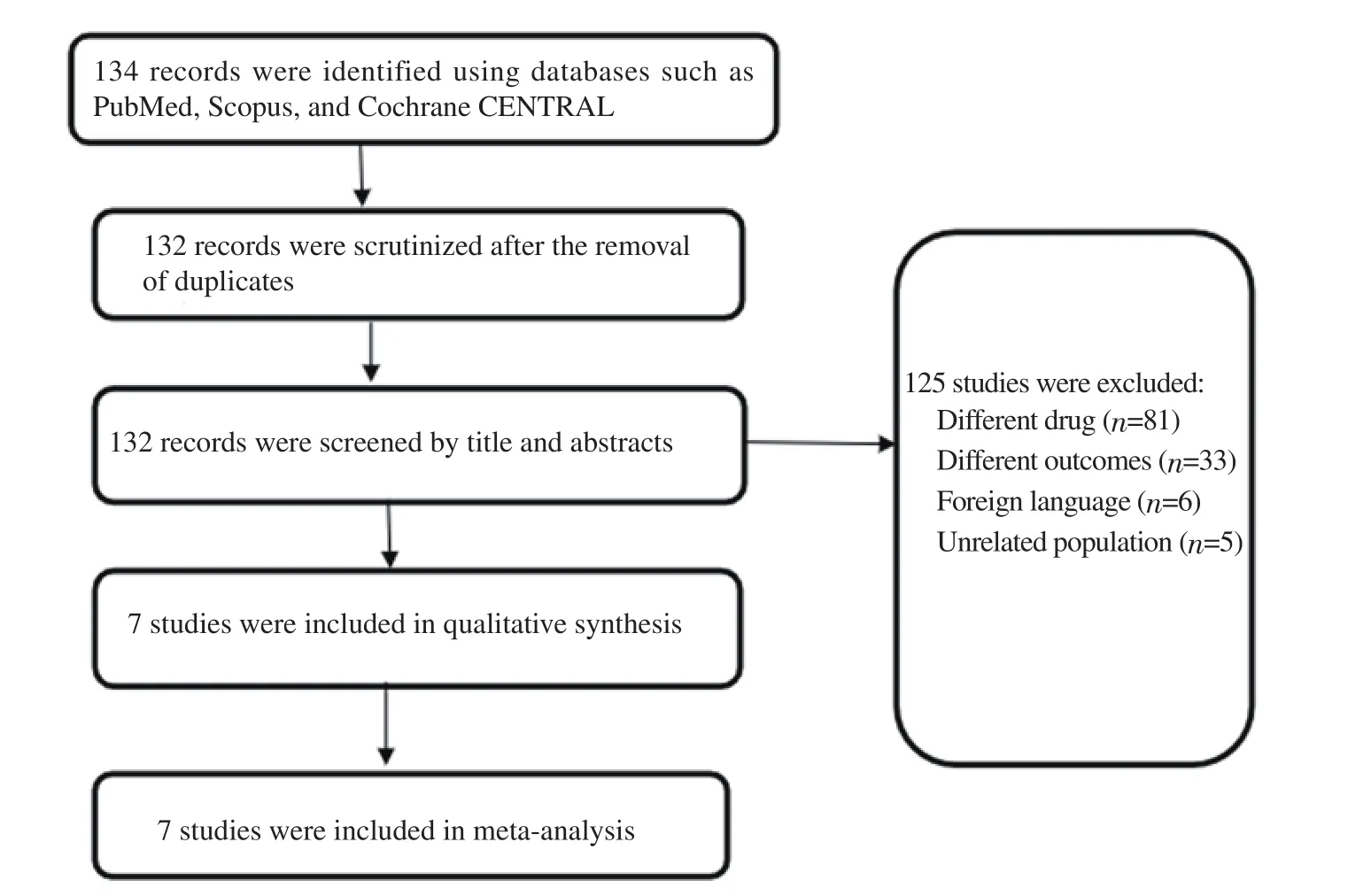

A total of 134 studies were found during search. Among them 125 studies were not included for reasons such as inappropriate drug, population was not the pregnant women, different outcomes and foreign language based on our exclusion criteria. As a result,a total of 7 studies were included in the analysis. The PRISMA flowchart of the selected studies is illustrated in Figure 1. The study characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1. The flow diagram of included studies in the review.

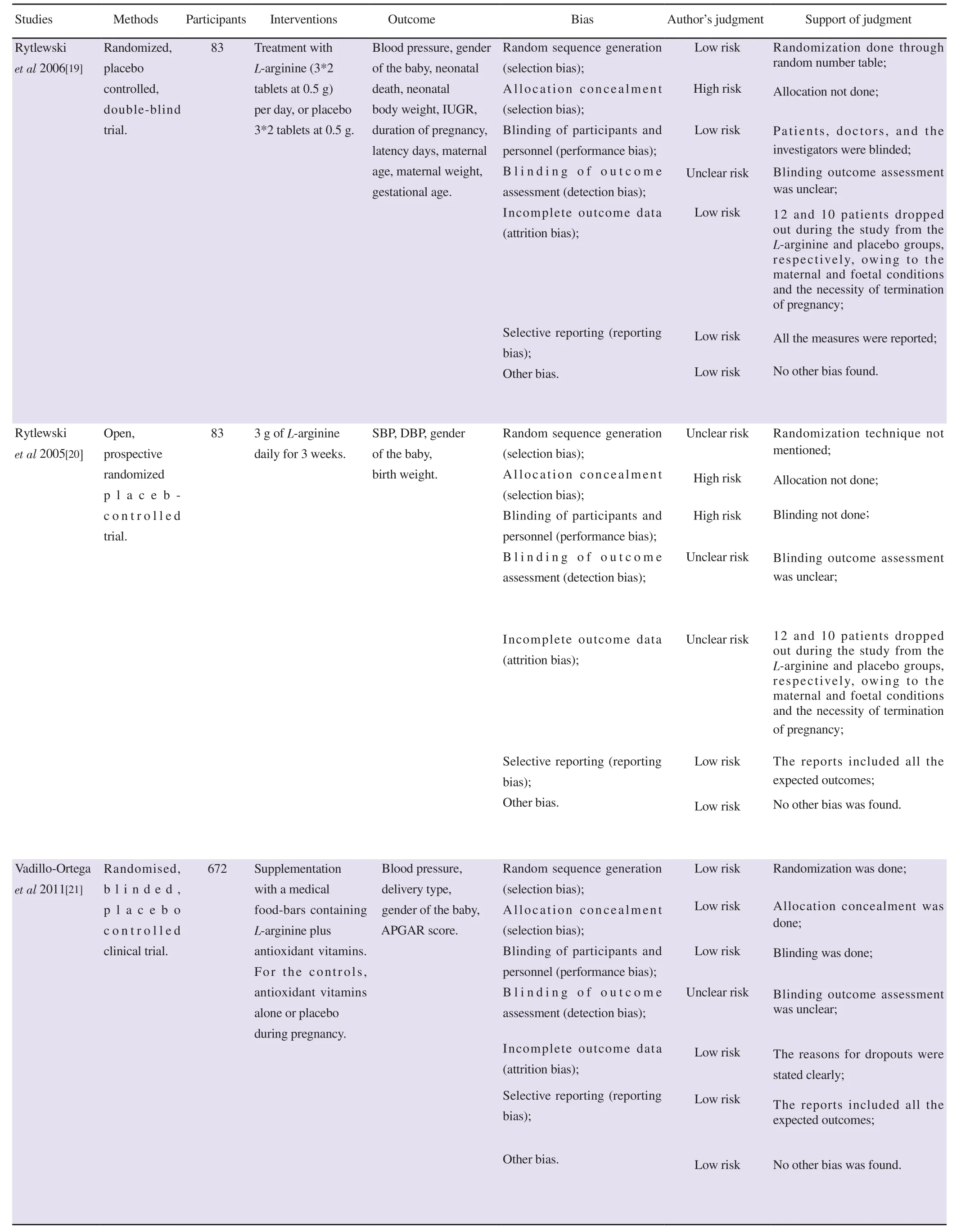

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

3.2. Effects of intervention

3.2.1. Primary outcome measures

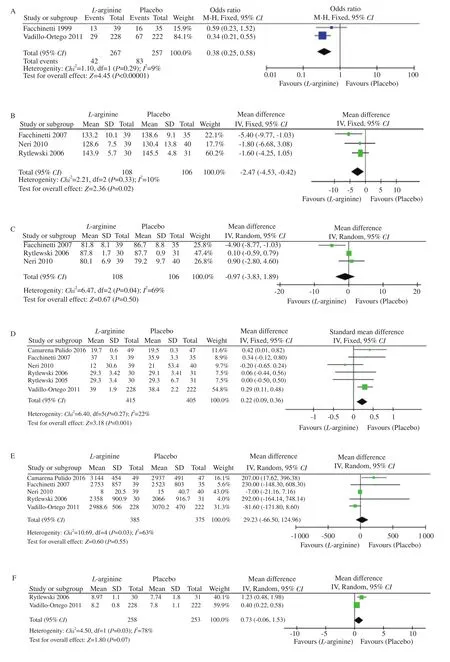

The two most primary outcomes included were preeclampsia and blood pressure (systolic and diastolic). Incidence of preeclampsia was measured in two studies published by Fachinetti et al[16] and Vadellio-Ortego et al[21] with a total of 267 participants in the L-arginine group and 257 in the placebo group. The heterogeneity was acceptable (I=9%, P=0.29,χ=1.10) and therefore the fixed effects model was used. The analysis from these studies showed that L-arginine was more effective in reducing the incidence of preeclampsia than placebo [odds ratio (OR)=0.38; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25, 0.58] (Figure 2A).

Reduction in the systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured in the remaining three studies reported by Fachinetti et al[17], Neri et al[18], and Rytlewskii et al[19] with a total of 108 participants in the L-arginine group and 106 in the placebo group. The heterogeneity of systolic blood pressure changes was acceptable (I=10%,P=0.33,χ=2.21). Thus, the fixed effects model was used to analyze the data. The results showed a reduction in systolic blood pressure in the group who were treated with L-arginine, when compared to the placebo group (MD -2.47; 95% CI -4.53, -0.42)(Figure 2B). Additionally, the study analysis revealed that L-arginine was efficacious than placebo in reducing diastolic blood pressure.As shown in Figure 2C, due to the high heterogeneity values(I=69%, P=0.04,χ=6.47), random effects model was used to analyze the data for diastolic blood pressure. The study results were statistically significant (MD -0.97; 95% CI -3.83, 1.89),indicating that L-arginine was more beneficial in reducing the diastolic blood pressure when compared to placebo, irrespective of the high heterogeneity.

3.2.2. Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures included the maternal and neonatal outcome measures. Maternal outcome measures like gestational age, latency and neonatal outcome measures like APGAR score and neonatal weight were analyzed.

Six studies were included in the analysis of gestational age. The heterogeneity of the studies was acceptable as shown in Figure 2D(I=22%, P=0.27,χ=6.40). Thus, the fixed effects model was used.L-arginine supplementation did not have any effects on gestational age and the results were not statistically significant [standard mean difference (SMD) 0.22; 95% CI 0.09, 0.36].

Five studies measured neonatal weight at birth, which was a secondary outcome. There was high heterogeneity among the studies included (I=63%, P=0.03,χ=10.69) and thus the random effects model was used to analyze the data which is shown in Figure 2E.The results were not statistically significant (MD 29.23; 95% CI-66.50, 124.96).

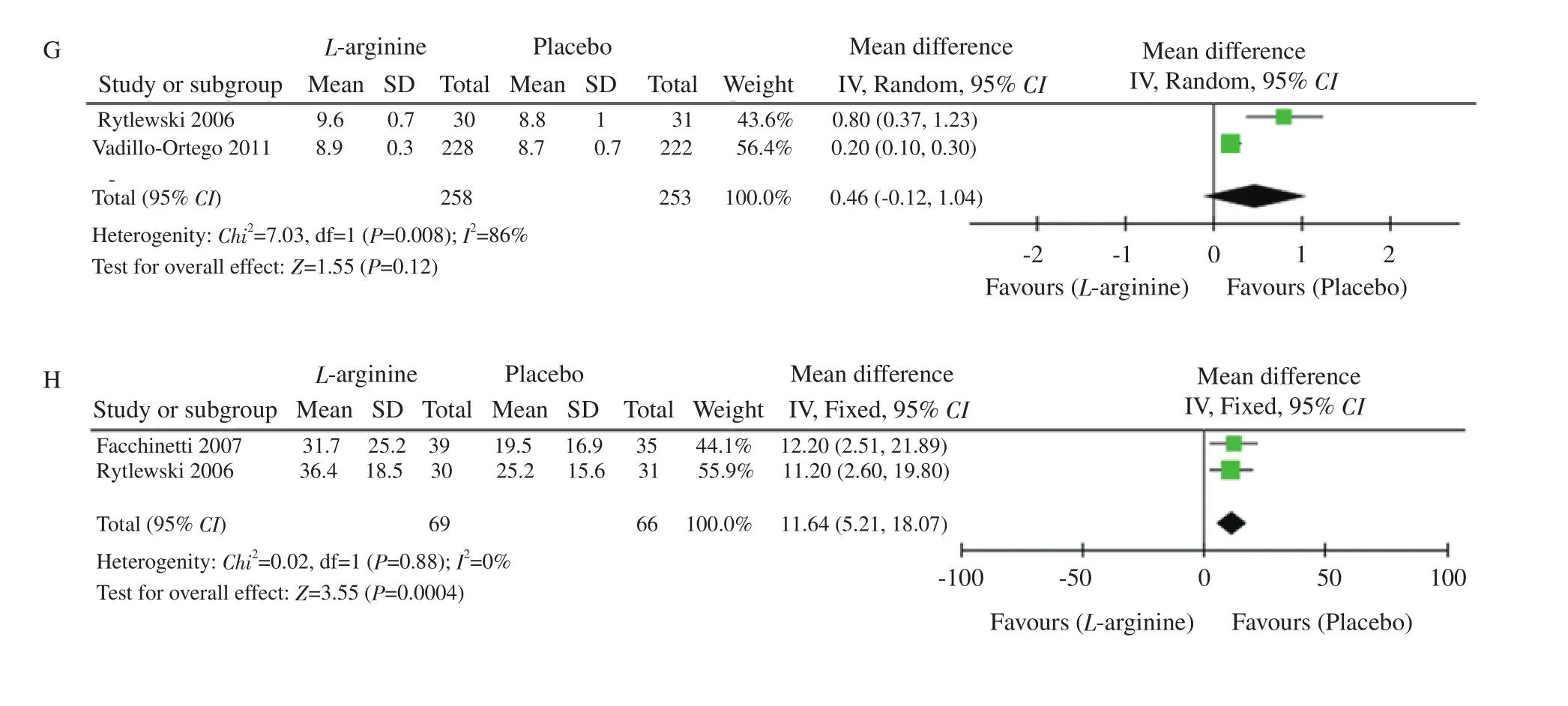

The APGAR score comprises five components: 1) colour, 2) heart rate, 3) reflexes, 4) muscle tone, and 5) respiration, each of which is given a score of 0, 1, or 2. The APGAR score quantitates clinical signs of neonatal depression such as cyanosis or pallor, bradycardia,depressed reflex response to stimulation, hypotonia, and apnea or gasping respirations. The score is usually reported at 1 minute and 5 minutes after birth for all infants, and for infants with score less than 7, the score is measured at 5-minute intervals until 20 minutes[22].Two studies measured the APGAR scores. The results were not statistically significant at APGAR at 1 minute (MD 0.73, 95% CI-0.06, 1.53) and APGAR at 5 minutes (MD 0.46; 95% CI -0.12,1.04). The heterogeneity between the studies was high, which was due to the large sample size in the study conducted by Vadellio-Ortego et al[21] and hence the random effects model was used. The heterogeneity was seen with the APGAR score at the 1st minute(I=78%, P=0.03,χ=4.50) and with the APGAR score at the 5th minute (I=86%, P=0.008,χ=7.03), as shown in Figure 2F and 2G,respectively.

Latency period is defined as the time between onset of premature rupture of membranes to either spontaneous delivery, labour induction at 34+0 weeks, or indicated delivery prior to 34+0 weeks because of suspected chorioamnionitis or non-reassuring foetal heart rate[23]. Two studies measured the latency of pregnancy as a secondary outcome. The results favored placebo and were not statistically significant (MD 11.64, 95% CI 5.21, 18.07). The heterogeneity among the studies were acceptable (I=0%, P=0.88,χ=0.02) which is depicted in Figure 2H.

Figure 2. Forest plots of incidence of preeclampsia (A), systolic blood pressure (B), diastolic blood pressure (C), gestational age (D), neonatal birth weight(E), APGAR score at 1 min (F) and at 5 min (G), and latency (H) between L-arginine and placebo.

Figure 3. Risk of bias summary: review author’s judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.3. Risk of bias assessment

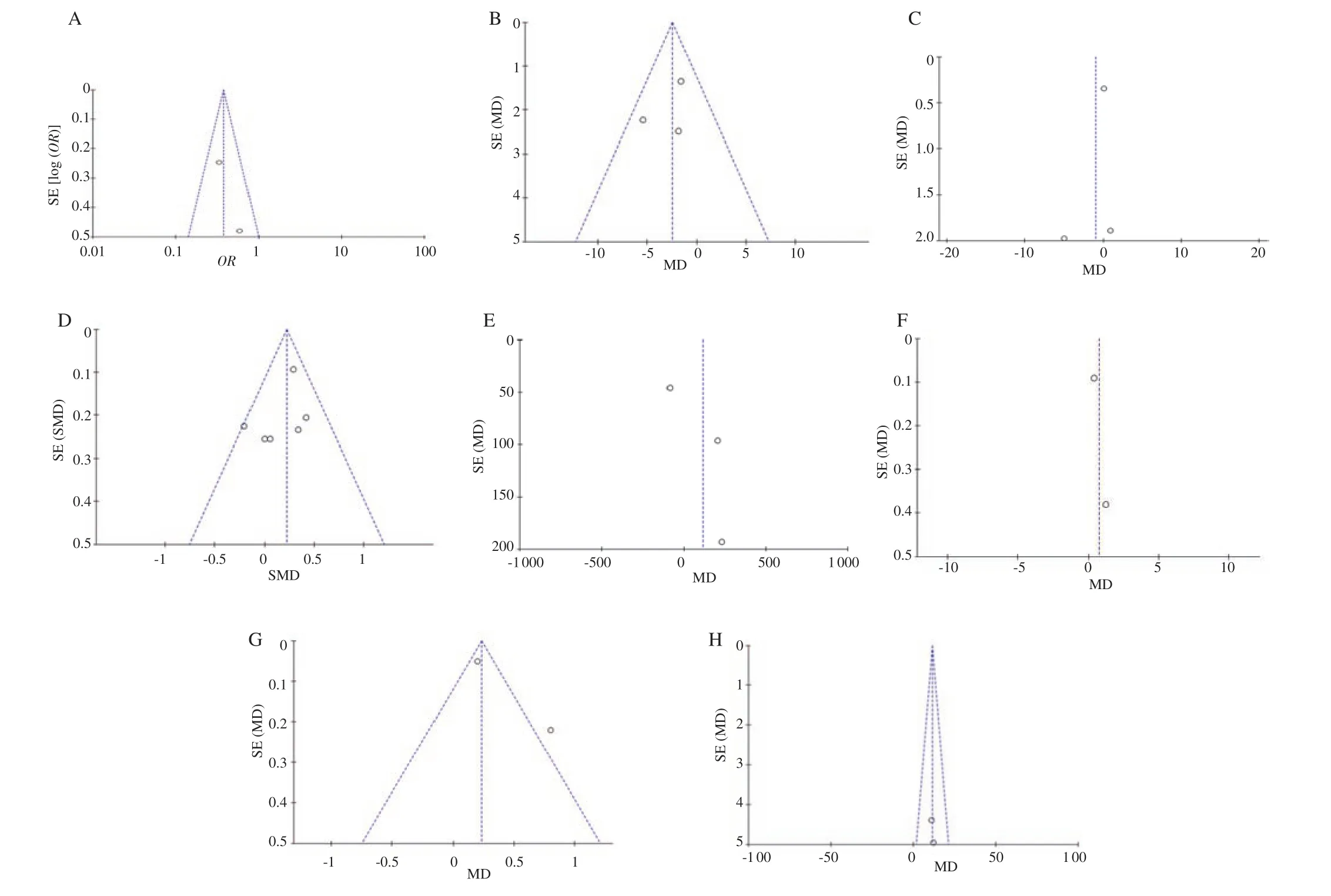

Risk of bias for the included studies is depicted in Figure 3 and its explanation is tabulated in Table 2. The funnel plot was created to assess the publication bias of the included studies for the primary and secondary outcome measures. We found the funnel plot was asymmetrical for the outcome measures of diastolic blood pressure,APGAR score of 5 minutes and neonatal weight. We need further more studies to be conducted to eliminate the reporting bias. The funnel plots for all the outcomes are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Funnel plots of L-arginine versus placebo in preeclampsia (A), systolic blood pressure (B), diastolic blood pressure (C), gestational age (D), neonatal weight (E), APGAR score at 1 min (F) and at 5 min (G), and latency (H). SE: standard error; MD: mean difference; SMD: standard mean difference; OR:odds ratio.

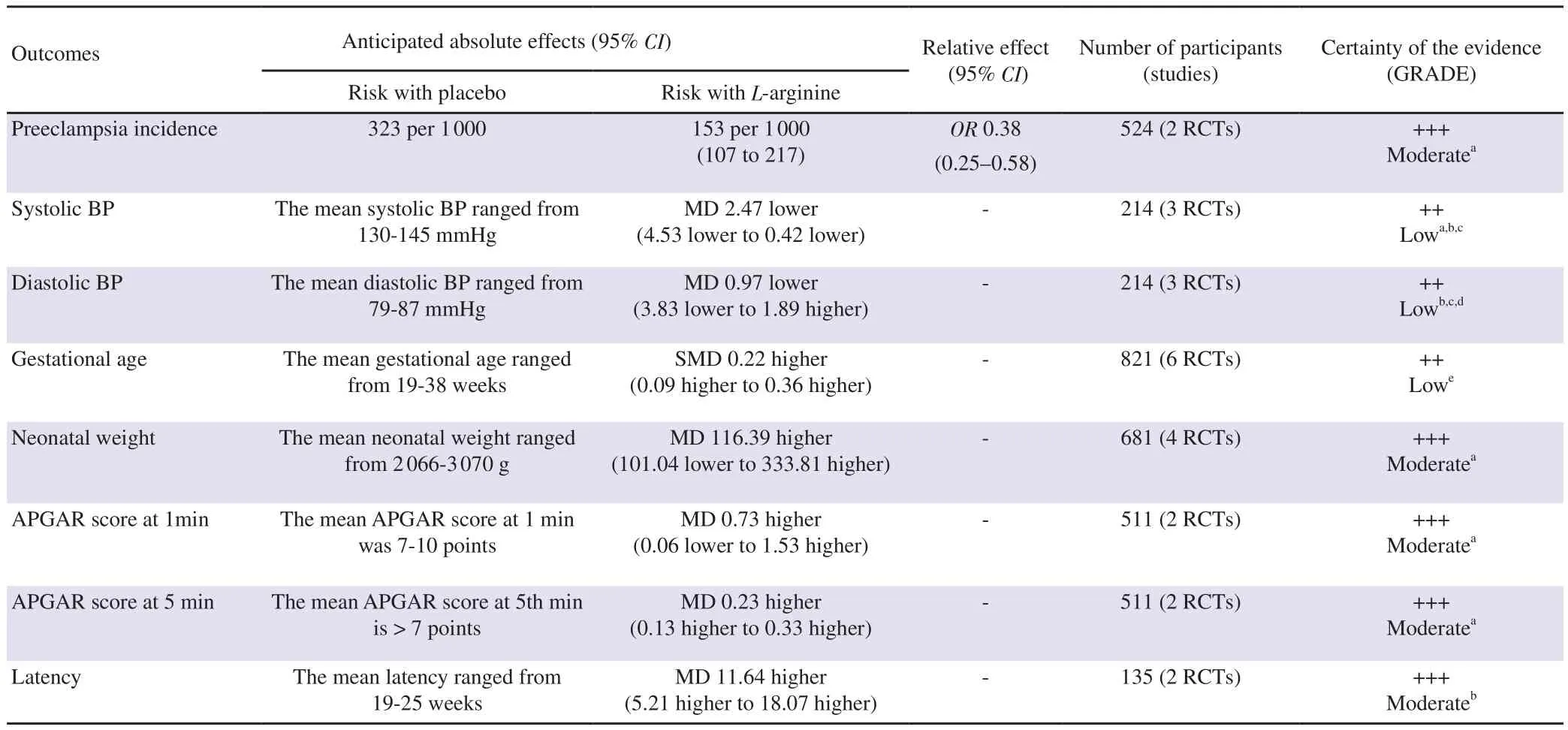

3.4. Outcome of GRADE approach assessment

The certainty of the extracted evidence was categorized into very low to high grades. The findings of L-arginine versus placebo in pregnant women experiencing preeclampsia are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2. Risk of bias assessment of the included studies.

Table 2. Continued.

Table 3. Summary of findings of L-arginine versus placebo in pregnant women experiencing preeclampsia.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the effect of L-arginine supplementation in preeclampsia was reviewed. L-arginine has shown to decrease the incidence of preeclampsia and reduce the systolic and diastolic blood pressure[15,19]. The studies which were included in this meta-analysis enrolled pregnant women who had condition of preeclampsia, and pregnant women with different gestational age, which made the baseline non-homogenous. Gestational age of pregnant women ranged from 14 to 32 weeks. Among the studies included, the dosage and methods of administration were different which made the baseline unbalanced. The studies which were included in this review included administration of L-arginine both parenteral and oral form. In one study, L-arginine plus antioxidant vitamin bars were given as supplementation. Though the route of the administration L-arginine was different, the results supported our primary outcome.

Among the included studies, four studies showed that L-arginine significantly reduced the blood pressure and prevented preeclampsia,when compared to the placebo group[15-17,20]. However, another study shows that L-arginine supplementation in women with mild chronic hypertension did not statistically affect the overall reduction in blood pressure, but it reduced the intake of a few antihypertensive medications. But the limitation of this study was the small sample size and exclusion of the patients with severe chronic hypertension[18].L-arginine with antioxidant vitamins supplementation was used as an intervention in a study, which significantly reduced the occurrence of preeclampsia in high-risk pregnant women. However, the study could not define the contribution of L-arginine when combined with vitamins in reducing the risk of preeclampsia[21]. The results of our review were consistent with previous studies[15-17,20], as it favors L-arginine in reducing the incidence of preeclampsia. Reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure was significantly found in our analysis. Even though diastolic blood pressure favored L-arginine,it showed higher heterogeneity for which the reason could not be established after performing the sensitivity analysis.

In addition to the reduction in blood pressure, the L-arginine group reported secondary outcome variables which were analyzed with respect to smaller number of preterm births, increased birth weight[15] and prolongation of pregnancy in patients with gestational hypertension[16,17]. But we could not find the impact of L-arginine on maternal and neonatal outcomes like gestational age, latency of pregnancy, neonatal body weight, APGAR (at 1 minute and at 5 minutes), as these outcomes were not statistically significant. Further studies are required to evaluate the impact of L-arginine on both maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Among the studies included in our review, the most reported adverse effects in L-arginine group were dyspepsia, diarrhea, nausea,vomiting, dizziness, palpitation, headache, and abdominal pain.L-arginine supplementation can be considered safe in pregnant women, as only four of the included studies reported adverse effects.Among the adverse effects reported, dyspepsia was more common(28.5%), while the others were only 1%-2%[15-17,21].

It is important to assert the strengths of our review. Firstly, our review considered the studies which had both oral and parenteral supplementation of L-arginine. Besides the baseline being unbalanced, the results were statistically significant. Secondly,the studies were conducted at different parts of the world, thereby clearing the obscureness of the relevance of results on region specific population. There were several limitations in our meta-analysis.Firstly, the sample size of the included trials was comparatively smaller. The participants involved in the analysis of preeclampsia were 267 in the L-arginine group and 257 in the placebo group.Whereas the participants who were included in the analysis to understand the reduction of blood pressure were only 108 in the L-arginine group and 106 in the placebo group. The evaluation of outcomes was different among the included studies, which led to the difficulty in data collection and in analyzing the outcomes.

In conclusion, in this systematic review and meta-analysis,L-arginine supplementation both in oral and parenteral form is found to be effective against placebo in lowering the systolic the systolic and diastolic blood pressure in patients with preeclampsia. However,the supplementation of L-arginine has no significant effects on maternal and neonatal outcomes like gestational age, latency of pregnancy, APGAR score and neonatal weight. Further larger randomized controlled trials are required to evaluate the beneficial role of L-arginine supplementation among pregnant women with preeclampsia.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank, JSS College of Pharmacy, JSS Academy of Higher Education & Research, Rocklands, Ooty, The Nilgiris, Tamilnadu,India for providing the research infrastructure and support.

Authors’ contributions

Roopa Satyanarayan Basutkar, Oorvashree Sri Hari, and Shonitha Sagadevan were involved in framing the protocol. Gopi Ramalingam, Mohamed Jahangir Sirajudeen, Oorvashree Sri Hari and Shonitha Sagadevan had conducted the search, data extraction and bias assessment. All disagreements were sorted and verified by Roopa Satyanarayan Basutkar. Gopi Ramalingam and Mohamed Jahangir Sirajudeen had entered the data into Review Manager 5.4 and conducted the analyses. The summary of findings table was prepared by Oorvashree Sri Hari and Shonitha Sagadevan.The final manuscript was prepared by Oorvashree Sri Hari,Shonitha Sagadevan and Roopa Satyanarayan Basutkar. The drafted manuscript was reviewed by Roopa Satyanarayan Basutkar and all other review authors approved the final version for publication.

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2021年6期

Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction2021年6期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Reproduction的其它文章

- Folic acid protects against fluoride-induced oxidative stress and testicular damage in rats

- Quality of life of infertile couples in the Gaza Strip, Palestine

- Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in pregnancy-associated maternal complications:A review

- Protective effects of honey compound syrup on busulfan-induced azoospermia in male rats

- Association between eNOS gene promoter polymorphism (-786T>C) and idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss in Iranian women