Anti-inflammatory and antipyretic potential of Arbutus andrachne L. methanolic leaf extract in rats

Sahar M. Jaffal, Sawsan A. Oran, Mohammad I. Alsalem

1Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, The University of Jordan, 11942 Amman, Jordan

2Department of Anatomy and Histology, Faculty of Medicine, The University of Jordan, 11942 Amman, Jordan

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Arbutus andrachne; Anti-inflammatory; Antipyretic;PGE2; IL-6; TRPV1; CB1; α2-ARs

1. Introduction

Inflammation is a natural biological process that occurs in response to harmful stimuli[1]. During inflammation, several inflammatory mediators are released at the injured tissue to induce vasodilation in addition to leakage of plasma, fluids, and white blood cells into the site of inflammation to start tissue repair[1]. Pyrexia (fever) is another normal response initiated in the body to fight infection[2].It is a complex process described as a rise in body temperature triggered by exogenous or endogenous stimuli known as pyrogens[2].Notably, some common mediators take part in the development of inflammation and fever such as prostaglandin E(PGE) and interleukin-6 (IL-6)[2]. PGEincreases vascular permeability and strengthens the role of other inflammatory mediators[3]. Also, PGEcontributes to the increase in body temperature by acting on the thermoregulatory center in the hypothalamus[4]. Besides, IL-6 is a multifunctional cytokine that evokes the production of many proteins responsible for inflammatory reactions[5]. Different types of cells(e.g. fibroblasts, endothelial and epithelial cells) produce IL-6[5].Importantly, IL-6 is a vital mediator in the transition from acute to chronic phase of inflammation[6]. It issues a warning signal in case of environmental stress conditions (e.g. tissue damage or infection)leading to the activation of defense mechanisms[6]. Unfortunately,currently used anti-inflammatory and antipyretic drugs have undesirable effects urging the need to find new anti-inflammatory and antipyretic candidates. In this regard, medicinal plants are rich sources for compounds that have promising therapeutic values with a wide margin of safety[7]. In Jordan, there are 363 medicinal plants including Arbutus andrachne (A. andrachne) L. (Ericaceae) which is a flowering tree that grows in Jordan in the regions of Jarash, Ajloun,Irbid, Salt, and Amman[8]. The plant is used as an edible plant, in traditional medicine as well as stain industry[9]. In particular, the leaves and fruits of A. andrachne are consumed as laxatives, blood tonic, diuretics, and antiseptics[9]. Several biological studies were conducted to explore the effects of A. andrachne in different models.Most importantly, A. andrachne extract showed strong anti-nociceptive activity[10]. In addition, 17 active compounds were identified in A.andrachne methanolic leaf extract by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS)[10]. The compounds include linalool, lauric acid,myristic acid, linoleic acid, rutin, arbutin, hydroquinone, β-sitosterol,ursolic acid, isoquercitrin, myricetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnosides, quercetin,gallic acid, (+)-gallocatechin, kaempferol, catechin gallate, and α-tocopherol[10].

Although many reports were published about the biological activities of A. andrachne, to the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies explored the in vivo anti-inflammatory and antipyretic effects of A. andrachne and its mechanism of action. In the present study, we examined the roles of A. andrachne methanolic leaf extract on carrageenan-induced paw edema and yeast-evoked pyrexia models as well as the mechanisms of action that underlie these effects. We focused on investigating the role of the transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1), cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), and alpha-2 adrenergic receptor (α2-AR) in the antiinflammatory and antipyretic activities of A. andrachne. TRPV1 is a non-selective cation channel that is involved in many processes including thermoregulation, different painful and inflammatory conditions[11,12]. Due to the diverse roles of TRPV1, many disorders and diseases were associated with alterations in the expression and/or function of TRPV1 such as asthma, inflammation, and itch[13,14].Furthermore, CB1 receptor is one of the CB receptors that take part in inflammation and pyrexia[15]. Importantly, it was reported that the endocannabinoid arachidonoylethanolamine enhances lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced fever by the activation of CB1 receptor[15]. Also, Alsalem et al. pointed out that the intra-articular injection of synthetic cannabinoids and palmitoylethanolamide to a rat model of arthritis restored paw withdrawal threshold and weightbearing differences[16]. Furthermore, the peripheral administration of anandamide inhibited thermal hyperalgesia through CB1 receptor in a carrageenan-induced edema model in rats[17]. With respect to the noradrenergic system, it is well recognized that noradrenergic receptors play pivotal roles in pain and inflammation and are considered targets for inflammatory and neuropathic pain treatment[18]. It was reported that the intrathecal application of α2-AR agonist clonidine alleviated complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced pain and produced changes in several signaling molecules[18].

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

SR141716A, capsazepine, and yohimbine were purchased from Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK. Diclofenac sodium was brought from Novartis, Basel, Switzerland. Lambda (λ)-carrageenan was ordered from Santa-Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, USA. Commercially available dried baker’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was purchased from the market, Amman, Jordan. PGEkit was supplied by Abcam, Cambridge, UK while IL-6 kit was from RayBiotech,Norcross, USA. Diethyl ether was purchased from Scharlau,Barcelona, Spain. Sterile normal saline was from McKesson,Virginia, USA.

2.2. Preparation of drugs

The stocks of antagonists (except yohimbine) were initially dissolved in absolute ethanol (10 mM capsazepine, 1 mM SR141716A). All drugs were freshly prepared (from stock) before use and were diluted in sterile saline. Yohimbine and diclofenac sodium were directly dissolved in saline. Hot saline (80 ℃) was used to dissolve λ-carrageenan while warm saline (40 ℃) was used to dissolve the baker’s yeast.

2.3. Collection of the plant leaves

The leaves of A. andrachne were gathered from Jarash, Jordan in March 2019. The plant was authentically identified by a plant taxonomist (Prof. Sawsan Oran) in the Department of Biological Sciences, the University of Jordan. A voucher specimen(UJ/05/2020) was placed at the herbarium, Department of Biological Sciences, the University of Jordan.

2.4. Preparing the methanolic extract from A. andrachne leaves

The leaves of A. andrachne were washed, dried, and ground with a blender. Methanol (10:1 v/w ratio) was used to soak the dried leaves with shaking at room temperature for 3 d. The extract was filtered by Whatman filter paper followed by evaporating the solution in a rotary evaporator maintained at 45 ℃ under reduced pressure. The procedure was repeated several times. The extract was weighed to calculate the yield percentage using the following equation: Yield% = (weight of dry extract/weight of dry leaves before extraction) ×100%. The extract was kept in an air tight container in the freezer.

2.5. Animals

Male Wistar rats (200-250 g) were used in the experiment of carrageenan-induced edema (n=54) while rats weighing 70-100 g were used in the experiment of yeast-induced pyrexia (n=54). All animals were brought from the animal house, the University of Jordan and were kept at the same unit in a temperature-controlled environment [(22 ± 1) ℃] with a cycle of 12 h lightness and 12 h darkness. Food pellets and water were provided ad libitum. The animals were allowed to adapt to the experimental room’s conditions before conducting the tests.

2.6. Carrageenan-induced paw edema

The anti-inflammatory effect of A. andrachne extract was examined using a carrageenan-induced paw edema model in rats. Paw size was determined before and after carrageenan injection by wrapping a thread around the paw of rats and measuring the thread’s length (paw circumference) using a metric ruler. The animals were divided into control and experimental groups. Different groups received vehicle or plant extract (150, 300, and 600 mg/kg body wt) intraperitoneally(i.p.) while the positive control group received diclofenac sodium(30 mg/kg body wt, i.p.) 30 min before intraplantar (i.pl.) injection of 1% w/v freshly prepared λ-carrageenan (100 μL/paw) into the left hind paw. The injection of carrageenan was performed under 2%diethyl ether anesthesia. Different antagonists were used to explore the extract’s mechanism of action in inducing its anti-inflammatory effect as the following: 0.1 mg/kg body wt capsazepine (a selective TRPV1 antagonist), 0.1 mg/kg body wt SR141716A (a selective CB1 antagonist), and 1 mg/kg body wt yohimbine (a selective antagonist for α2-AR). The antagonists were i.p. administered 30 min before the chosen dose of A. andrachne extract (300 mg/kg body wt). The behavior of animals was noticed and recorded in all treated groups. Paw size was measured in all animals after 1, 2, 3,and 4 h of carrageenan injection. Images for paws’ plantar surface of different rats were captured before and after treatment using a digital compact camera (Canon, Melville, USA). The percentage of edema was calculated using the following equation: [(C-C)/C]×100% where Cis the paw thickness after carrageenan injection,Cis the paw thickness before carrageenan injection (baseline). The animals were sacrificed after 5 h of carrageenan injection to collect blood samples from the heart of rats. The blood was kept for 30 min at room temperature to allow blood coagulation and separate the serum. Samples were then centrifuged at 1 300 ×g for 15 min. The supernatant was preserved at -20 ℃ before use for determining the levels of IL-6 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

2.7. Determination of IL-6 levels in serum samples

All reagents and IL-6 standards (0-10 000 pg/mL) were prepared as explained by the manufacturer. The standards or samples (100 μL)were added to each well and incubated at room temperature with gentle shaking for 2.5 h. The wells were washed with 1× wash buffer 4 times. The remaining wash solution was removed by blotting the plate against paper towels. After that, 100 μL of 1× biotinylated antibody was added and incubated with shaking for 1 h at room temperature followed by 4 times wash as in the previous step. The next step included the addition of 100 μL streptavidin, and 45 min incubation at room temperature with gentle shaking followed by 4 times wash. Subsequently, 100 μL of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine substrate was added and incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Finally, 50 μL stop solution was added to yield a yellow colour that can be photometrically measured at 450 nm. The added volumes that were mentioned in this section represent the volumes per every well. Calculations of IL-6 levels in different samples were performed based on the standard curve.

2.8. Yeast-induced pyrexia

To evaluate the effect of the plant extract on yeast-evoked pyrexia, the experiment was conducted in a temperature-controlled environment[(22 ± 1) ℃]. Digital thermometer was used to determine the body temperature of each rat before and after treatments. The thermometer was inserted into the rectum for 45 s. Pyrexia was induced by i.p.injection of 20% baker’s yeast dissolved in normal saline (20 mL/kg body wt). Following yeast injection, the animals were kept to fast for 6 h with water provided ad libitum. After 6 h, body temperature was measured to select the animals that had a rise between 0.5-1 ℃ and then they were divided into different groups. After that, the animals received i.p. injection of different treatments including various doses of the plant extract (150, 300, and 600 mg/kg body wt), vehicle, or diclofenac sodium. Different antagonists were used in this part of the experiment as the following: 0.1 mg/kg body wt capsazepine,0.1 mg/kg body wt SR141716A and 1 mg/kg body wt yohimbine.The antagonists were i.p. administered 30 min before A. andrachne extract (300 mg/kg body wt). In all groups, body temperature was measured every 1 h. The percent change in yeast-evoked body temperature was calculated using the following equation: (T-T)/(T-T)×100% where Tis the temperature measured after treatments,Tis the temperature measured post yeast injection (after pyrexia), and Tis the baseline temperature, measured before yeast injection. After 5 h of the final treatment, the animals were euthanized to collect blood samples from the heart. The blood samples were kept to coagulate for 30 min at room temperature and were centrifuged at 1 300 ×g, 4 ℃ for 15 min. The supernatant was preserved at -20 ℃ to determine PGElevels.

2.9. Determination of PGE2 levels in serum samples

PGElevels in different serum samples were determined using ELISA kit. All reagents were prepared according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, the standards, samples, or diluent solutions were prepared and added to the 96-well plate provided in the kit. After the addition of PGEand alkaline phosphatase,the standards and samples were exposed to PGEantibody with shaking at room temperature for 2 h followed by 3 times wash.The excess wash buffer was removed by tapping the 96-well plate onto paper towels followed by the addition of the p-nitrophenyl phosphatesubstrate and stop solution. Afterwards, the optical density was measured at 405 nm with correction at 590 nm pursuant to the manufacturer’s instructions. Calculations of PGElevels in different samples were performed based on the standard curve.

2.10. Open field test

The locomoter activity of all animals was examined by the open field test using Opto-M4, Columbus instrument. The instrument contains dual horizontal planes with infrared beams placed on the top of the cage. On the bottom of the cage, there are detectors that detect beams’ interruption by the movement of the animal crossing the infrared beam. The number of beam interruptions was summed every 5-20 min by the instrument software and was sent to a computer being connected to the machine. The results were displayed on the software and exported to excel file.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard error of means (SEM).The normality test was conducted for all groups using Shapiro-Wilk test. The statistical significance of difference between groups was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the suitable post-hoc test (Tukey’s test). P<0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad Prism version 7 was used to create figures and perform the statistical analysis.

2.12. Ethical statement

All experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee at the University of Jordan (Ethical approval number 235/2020/19).

3. Results

3.1. Yield of A. andrachne methanolic leaf extract

Using the extraction method described in the methodology section,5 g of powder leaves (soaked in 50 mL methanol) produced 1.5 g extract (15% yield). The extract was used for screening its biological activities in animals.

3.2. Effect of A. andrachne leaf extract on carrageenaninduced inflammation

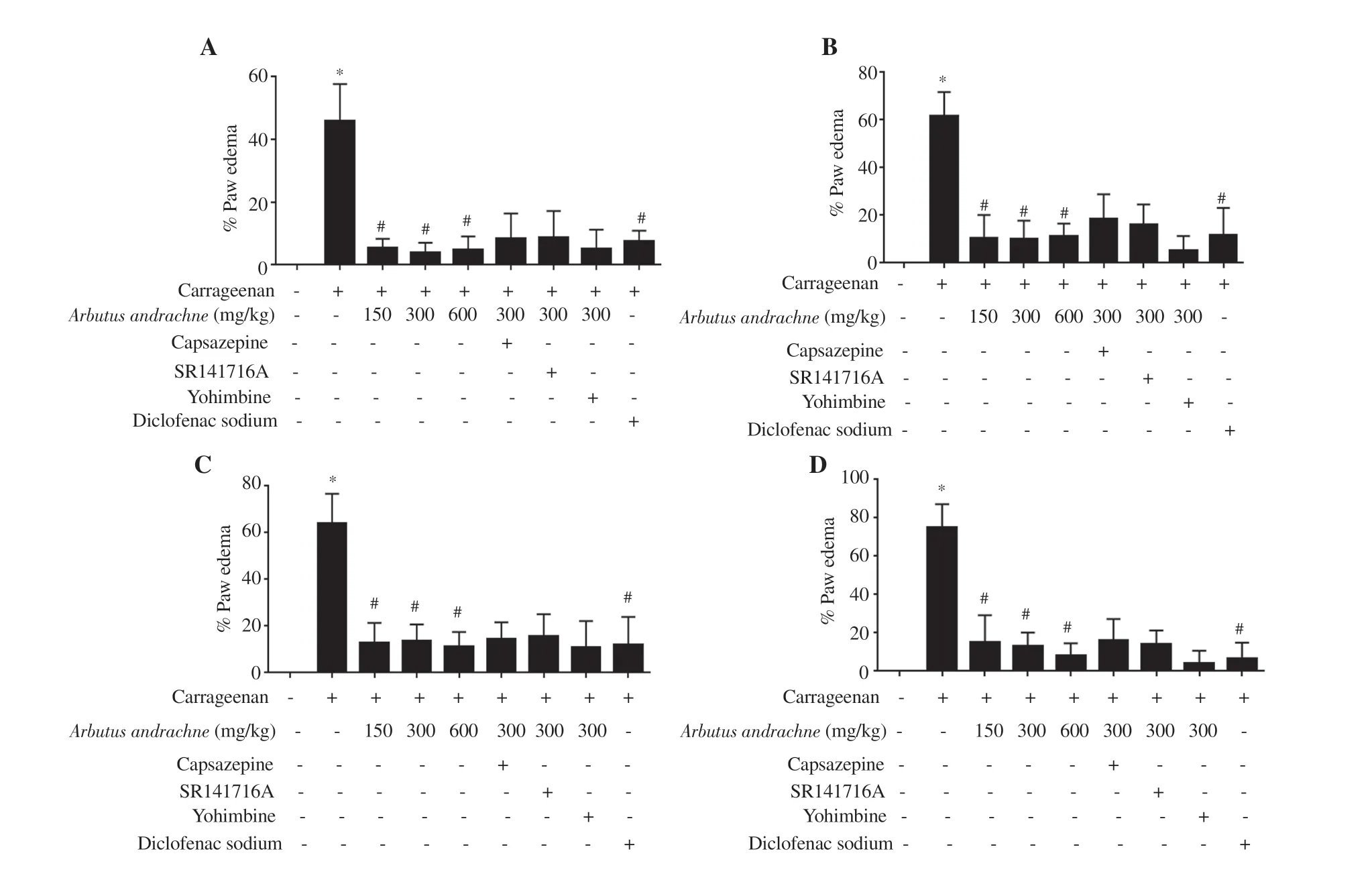

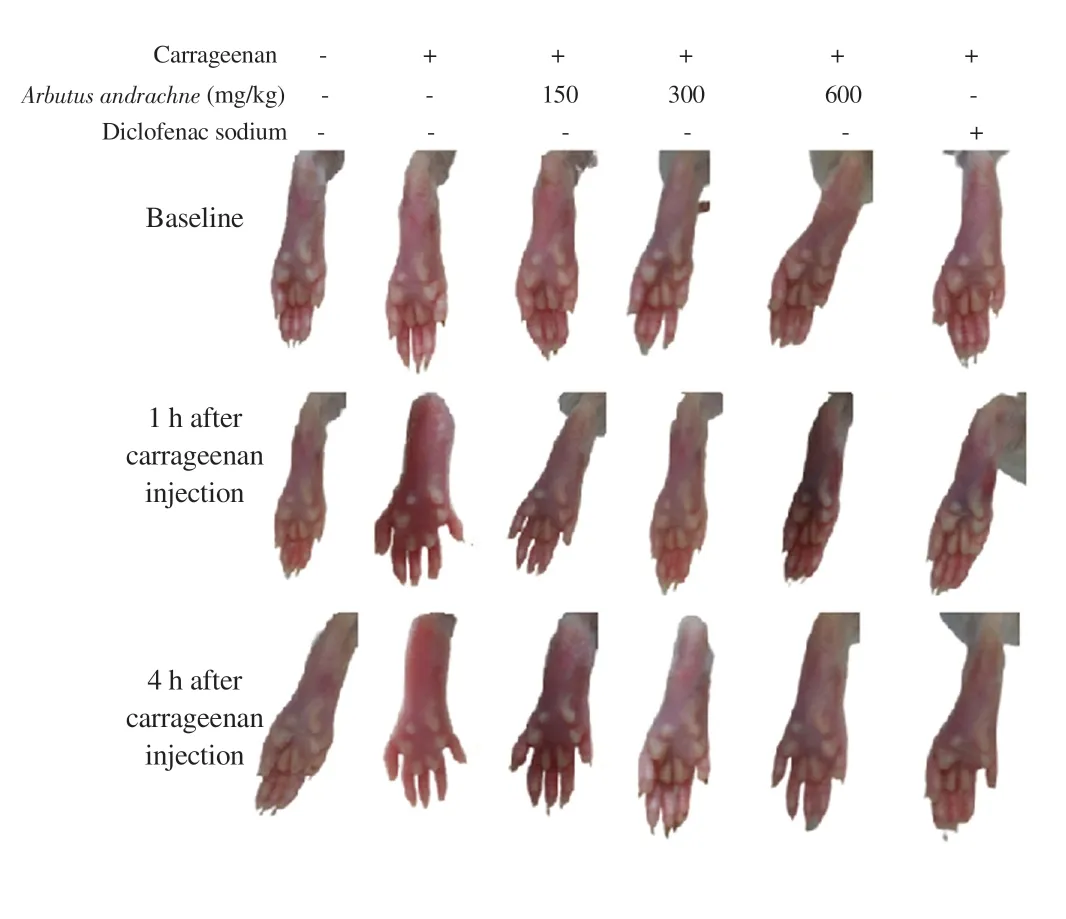

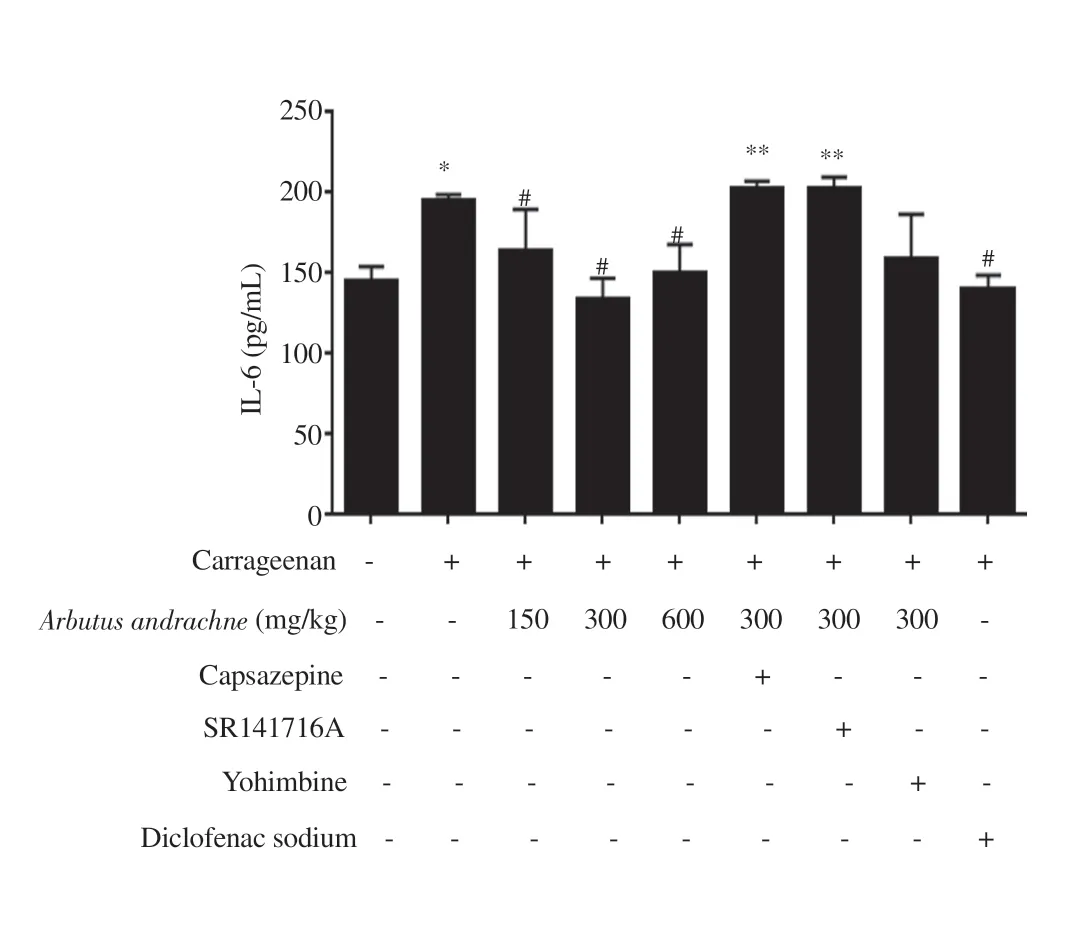

In this study, inflammation was induced by i.pl. injection of λ-carrageenan (1% w/v) into the hind paw of rats whereby the increase in footpad thickness was considered edema. The i.pl.injection of 1% carrageenan into the left hind paw of animals significantly increased footpad thickness by (45.96 ± 4.79)%, (61.44 ± 4.19)%,(63.97 ± 5.22)% and (75.10 ± 4.95)% after 1, 2, 3 and 4 h of injection,respectively. At 1-hour post carrageenan injection, the percentage of paw edema was lower in the groups that received different treatments: 150 mg/kg body wt (5.27 ± 1.00)%, 300 mg/kg body wt (4.02 ± 1.00)%,and 600 mg/kg body wt A. andrachne extract (4.90 ± 1.49)% as well as 30 mg/kg body wt diclofenac sodium (7.38 ± 1.45)% (Figure 1A).After 2 h of carrageenan injection, the percentage of paw swelling reached (10.55 ± 3.40)%, (10.15 ± 2.68)%, (11.35 ± 1.83)% and(11.78 ± 5.10)% in the groups that received 150, 300, and 600 mg/kg body wt A. andrachne as well as 30 mg/kg body wt diclofenac sodium, respectively (Figure 1B). In the third and fourth hour after carrageenan injection, the groups that were treated with 150, 300,600 mg/kg body wt A. andrachne extract and 30 mg/kg body wt diclofenac sodium still exhibited markedly lower percentage of paw edema compared with the carrageenan group (Figures 1C and D). Clearly, inflammation subsided in the groups that received the plant extract before carrageenan injection. Notably, paw thickness in A. andrachne-treated groups was comparable to the thickness in the group that received the standard drug diclofenac sodium at all measured time points. Figure 2 displays representative photographs(at selected time points) for the paw thickness of rats. Based on the aforementioned results, the most effective dose of A. andrachne leaf extract (300 mg/kg body wt) was chosen to examine the impact of different antagonists on the anti-inflammatory effect exhibited by the extract. None of the antagonists used in this study abolished or decreased the noticeable activity of the extract on carrageenaninduced edema at any time point (Figures 1A-D). Moreover, the i.pl. injection of carrageenan increased IL-6 levels significantly compared with the control group while A. andrachne leaf extract(150, 300, and 600 mg/kg body wt) attenuated IL-6 levels compared with the carrageenan-treated group (Figure 3). Notably, only TRPV1 and CB1 antagonists abolished the effect of 300 mg/kg body wt A.andrachne on IL-6 levels in the carrageenan-induced paw edema model. It was also noted that there were no toxic signs in the skin,eyes, behaviour (salivation, lethargy, and sleepiness), urination,diarrhea, or mortality in any of the groups that received different doses of A. andrachne extract used in this study. Moreover, the i.p.injection of the methanolic leaf extract did not affect the locomotor activity of animals when tested in the open field test (data not shown)ruling out the possibility that there was sedative effect or impairment in animal locomotion.

Figure 1. Percentage of paw edema in rats receiving different treatments after 1 (A), 2 (B), 3 (C) and 4 (D) h of carrageenan injection. The data are presented as mean±SEM (n=6), and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. *Significant difference vs. the control group, P<0.001. #Significant difference vs. the carrageenan-treated group, P<0.001.

Figure 2. Photographs showing paw sizes over time in different treatment groups.

Figure 3. IL-6 levels in different treatment groups. The data are presented as mean±SEM (n=6), and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *Significant difference compared with the control group, P<0.001.#Significant difference compared with the carrageenan-treated group,P<0.001. **Significant difference compared with the 300 mg/kg body wt A.andrachne treated group, P<0.001.

Figure 4. Percent change in rectal body temperature in different groups after 1 (A), 2 (B), 3 (C) and 4 (D) h of A. andrachne extract treatment. The data are presented as mean±SEM (n=6), and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. #Significant difference compared with the yeast-treated group,P<0.001. **Significant difference compared with the 300 mg/kg body wt A. andrachne and yeast-treated group, P<0.001.

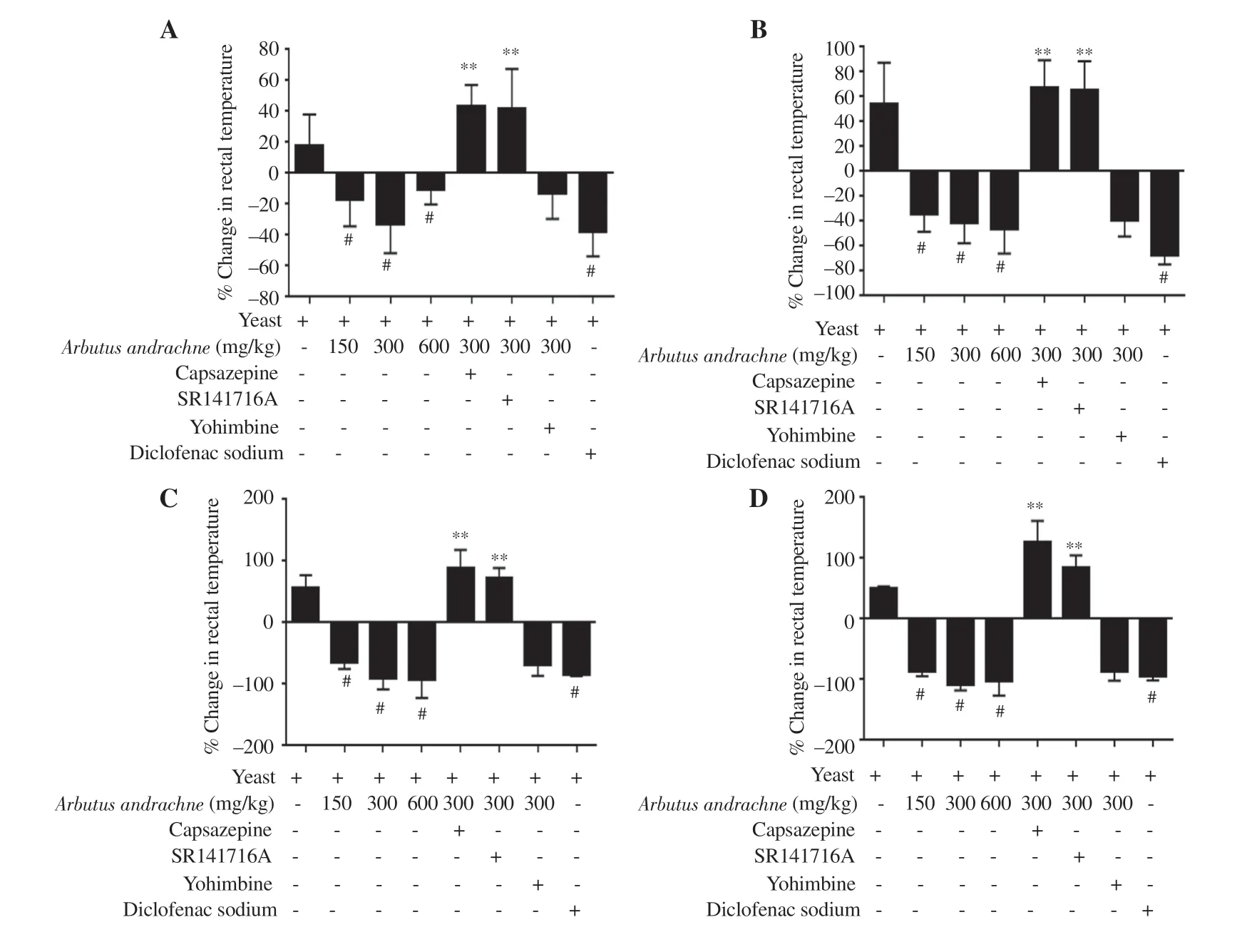

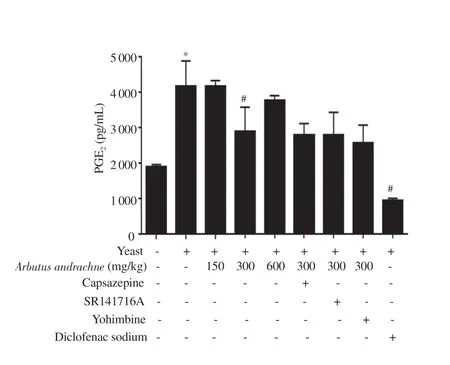

3.3. Effect of A. andrachne leaf extract on yeast-evoked pyrexia

A yeast-evoked pyrexia model was employed to screen the antipyretic effect of the plant extract and the role of different receptors in mediating its activity. The i.p. injection of 20% yeast suspension(20 mL/kg) had a robust effect on body temperature of animals and induced fever after 6 h of injection. Yeast injection increased body temperature by (17.51 ± 9.20)%, (53.90 ± 13.71)%, (55.76 ± 9.50)%and (49.75 ± 2.10)% after 1, 2, 3 and 4 h, respectively. Similar to the activity of diclofenac sodium, the i.p. injection of A. andrachne extract decreased yeast-induced elevation in body temperature after 1, 2, 3,and 4 h of injection (Figures 4A-D). The maximum antipyretic effect was noticed in the group that received 300 mg/kg body wt A. andrachne extract. Accordingly, this dose was selected to assess the involvement of certain receptors in the animals’ response to the plant extract. Of the antagonists administered before 300 mg/kg body wt A. andrachne,only TRPV1 and CB1 antagonists reversed the effect of the plant extract in reducing pyrexia at all measured time points (Figures 4AD). As expected, the administration of yeast increased PGElevels significantly (4 164 ± 277) pg/mL compared with the control group(1 910.00 ± 25.43) pg/mL. Interestingly, there was a dramatic decrease in PGElevels [(2 893 ± 285) pg/mL] in the group that received 300 mg/kg body wt A. andrachne leaf extract compared with carrageenantreated group (Figure 5). This decrease was not abrogated by preinjecting the animals with TRPV1, CB1, or α2-AR antagonists.

Figure 5. PGE2 levels in different tretament groups. The data are presented as mean±SEM (n=6), and analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. *Significant difference compared with the control group, P<0.001.#Significant difference compared with the yeast-treated group, P<0.001.

4. Discussion

There is an urgent need for new powerful anti-inflammatory and antipyretic drugs that have a good margin of safety. Medicinal plants are considered promising sources for therapeutic compounds and can be valuable candidates[7]. A large number of researches showed that A. andrachne had several biological activities. However, to the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies determined the anti-nociceptive, in vivo anti-inflammatory and antipyretic effects of A. andrachne. Previously, we showed that A. andrachne exhibited anti-nociceptive effect in different models[10]. The current study put the light on new valuable effects of A. andrachne leaf extract that was yet to be determined in previous studies. It proves potent anti-inflammatory and antipyretic potential of A. andrachne extract and validates its mechanism of action. In more detail, all doses of A. andrachne extract significantly decreased carrageenan-induced swelling in animal footpads indicating that A. andrachne is a regulator for inflammation. The effect was accompanied by a decrease in IL-6 levels. Interestingly, 17 compounds were identified in A. andrachne methanolic leaf extract by LC-MS[10]. These compounds have effects on inflammation and IL-6 levels as documented in earlier reports.Peana and co-workers reported the anti-inflammatory role of linalool in carrageenan-induced paw edema model after 1, 3, and 5 h of injection[19]. Moreover, Liu et al. found that treating neutrophils with 40 μM quercetin before LPS administration decreased the expression of IL-6 mRNA, intracellular IL-6, and IL-6 secretion[20]. Similarly,IL-6 suppression was reported by treatment with isoquercetin,β-sitosterol, and ursolic acid in different models[21-23]. Moreover, it was shown that α-tocopherol exhibited anti-inflammatory activities in human and animal studies[24]. The administration of α-tocopherol to the animals 3 d before LPS treatment attenuated IL-6 levels in cardiac and skeletal muscles[25]. Besides, Marion-Letellier and colleagues showed that linoleic acid diminished the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6[26]. Likewise, it was noted that lauric acid demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity in rats whereby rutin decreased ankylosis, edema, and nodules[27,28]. Also,arbutin exhibited anti-inflammatory properties in LPS-induced microglial cells and decreased IL-6 levels[29] while β-sitosterol had anti-inflammatory activities in different models of paw edema induced by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol acetate, arachidonic acid,and carrageenan in rodents[30]. Similarly, myricetin displayed anti-inflammatory roles in multiple models including rheumatoid arthritis, carrageenan-induced inflammation, xylene-induced ear edema, and periodontitis infectious inflammatory disease[31].Besides, much attention was paid to the broad spectrum of antiinflammatory activities exhibited by kaempferol[32]. Kroes et al.pointed out that gallic acid demonstrated an anti-inflammatory effect against zymosan-induced footpad swelling in mice[33]. It was also noted that epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibited the synthesis of IL-6 in adjuvant-induced arthritis rat model[34]. With respect to the antipyretic effect exhibited by the plant extract, the effect can be also ascribed to many active compounds of the plant that had antipyretic activities as reported in the literature. The reversal of yeast-evoked pyrexia was demonstrated after the use of virgin coconut oil that contains lauric, myristic, and linoleic acids as active ingredients[35].Additionally, Fawad et al. reported that 2 derivatives of hydroquinone significantly reduced the febrile response in rats[36]. Linalool, rutin,ursolic acid, β-sitosterol, isoquercetin, quercetin, gallocatechin,kaempferol, and gallic acid were also compounds identified in many plant extracts that demonstrated potent antipyretic effects in previous studies[37-41]. Importantly, the antipyretic effect of A. andrachne extract shown in the current study was accompanied by a decrease in PGElevels. In this regard, previous studies revealed that several flavonoids (e.g. quercetin and kaempferol) prevented LPS-induced PGEproduction[42]. Similar findings were reported for the effect of other compounds including isoquercetin, rutin, and myricetin on LPS-induced PGEproduction in macrophages[43]. Likewise, treating macrophages with α-tocopherol decreased PGElevels[44] while the administration of epigallocatechin-3-gallate attenuated the levels of PGEinduced by photofrin mediated photodynamic therapy[45].Of note, earlier reports showed the involvement of TRPV1 and/or CB1 receptor in the anti-nociception effects induced by the active constituents of A. andrachne extract. These reports are listed in detail in Jaffal et al.[10]. It merits explaining the involvement of TRPV1 and CB1 antagonists in reversing the effect of A. andrachne extract on serum IL-6 levels of the animals in carrageenan-induced paw edema despite not being implicated in the anti-inflammatory activity of the extract. Another fact that needs explanation is that the antagonists of the TRPV1 and CB1 receptors were implicated in abolishing the antipyretic effect of the extract but not PGElevels in serum samples that were taken from the animals in this model. In this regard, we previously found that the anti-nociceptive effect of the plant extract was mediated by several receptors including TRPV1, CB1, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α and gamma (γ)[10]. These receptors were differentially implicated in hot plate test, tail flick test and formalin-induced paw licking test. Therefore, we expect that other receptors are involved in A. andrachne-induced anti-inflammatory action or in the decrease of PGElevels evoked by A. andrachne extract in yeast-induced pyrexia model whereby TRPV1 and CB1 receptors were not involved. Further work is needed to investigate the involvement of other receptors in these activities of the leaf extract.

Notably, the present study had some limitations. Other inflammatory mediators should be determined to further confirm the effect of the A. andrachne extract and different models should be established to further evaluate the anti-inflammatory effects of the extract.

Taken together, the data of the current research proved potent antiinflammatory and antipyretic effects of A. andrachne leaf extract with a decrease in the levels of IL-6 and PGE. A. andrachne can be a good candidate for development of new anti-inflammatory and antipyretic agents with fewer side effects.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Deanship of Scientific Research, The University of Jordan.

Funding

This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research,The University of Jordan (235/2020/19).

Authors’ contributions

SMJ designed the experiments, collected, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the article. SAO collected and identified the plant and supervised the project. MIA designed the experiments,supervised the project, and critically read the article. All authors approved the final version of the published manuscript.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2021年11期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2021年11期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Phytochemicals, pharmacological and ethnomedicinal studies of Artocarpus: A scoping review

- Crotalaria ferruginea extract attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice by inhibiting MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways

- Chrysanthemum indicum ethanol extract attenuates hepatic stellate cell activation in vitro and thioacetamide-induced hepatofibrosis in rats

- Nanoemulsion containing a synergistic combination of curcumin and quercetin for nose-to-brain delivery: In vitro and in vivo studies