HPV prevalent types in a cohort of sexually active Nigerian women: implications for vaccination programmes

Azuka Patrick Okwuraiwe, Rosemary Ajuma Audu, Titiola Abike Gbajabiamila, Ifeoma Eugenia Idigbe, and Oliver Chukwujekwu Ezechi

Abstract—Background: The human papillomavirus virus (HPV) is very common with over 150 strains and at least 42 acquired by sexual contact. It is a public health concern among women the world over, with an estimated prevalence of 11.7% globally, and 24% in Sub-Saharan Africa. There are five common HPV types; HPV16, HPV18, HPV52, HPV31, and HPV58. Cervical cancer affects women globally, with estimated 570, 000 new cases in 2018. Nearly 90% of the 311,000 deaths worldwide in that year occurred in low- and middle-income countries. Objective: To estimate the prevalence of HPV among sexually active women in Lagos, Nigeria; and to determine the most common HPV type among that category. Methods: A descriptive cross-sectional study design was implemented, with 198 women in total enrolled for the study. Sexually active women from various health facilities in Lagos were screened by obtaining cervical tissue, stirred into PCR cell media, and assayed for HPV genotypes using the Roche COBAS® 4800 System. Results: Age of the women ranged from 18 to 65 years (mean 34.6 ± 6.4), with the majority (56.4%) between 25-34 years; 65% were married and 63% had a secondary education. Age at first penile-vaginal contact ranged from 9 to 38 years (mean 20.4 ± 3.9). Sixty-five percent of women stated total lifetime sexual partners of between 2 and 4 (mean 2.9 ± 2.5). The prevalence of high-risk HPV was 40.4% (95% CI: 40.1 to 40.7) and breakdown of types obtained were; HPV16, 2.5% (95% CI: 2.22 to 2.78); HPV18, 3.5% (95% CI: 3.22 to 3.78); other high risk (OHR) HPV, 28.3% (95% CI: 28 to 28.6); HPV16 & OHR HPV, 1.5% (95% CI: 1.22 to 1.78); HPV18 & OHR HPV, 4.1% (95% CI: 3.82 to 4.38); HPV16, 18 & OHR HPV, 0.5% (95% CI: 0.221 to 0.779). HPV negative and inconclusive results were 58.1% and 1.5% respectively. Conclusion: Prevalence of OHR HPV is high among Nigerian women. This informs the pattern of HPV existing in the African region, and may aid future efforts at eradicating the virus. The findings are further contributive evidence to the initiative to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health challenge in Nigeria.

Key words—HPV, Type, Cervical cancer, High-risk, Women, Prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a communicable viral infection often around or in the reproductive canal. Most sexually active women and men get infected at one point in a time in life, others more than once [1]. HPV is a sexually transmitted virus. The types that can cause cervical cancer and other types of cancer, such as cancers of the anus, vagina, vulva, penis and oropharynx are known as highrisk HPV [2]. High risk HPV DNA is found to exist in 99.7% of cervical cancer specimens [2], and its precursor cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) [3].

Cervical cancer is a very common HPV-related disease. Almost all cases of cervical cancer can be linked to HPV infection. Cervical cancers are a prevalent cause of mortality worldwide with 8.2 million deaths in 2012, and this trend has remained unchanged [1]. Viral infections contribute to 15–20% of all human cancers, whereby several viruses play considerable roles in the multistage development of malignant cancers. Cervical cancer has an estimated prevalence of 11.7% globally, and about 24% in Sub-Saharan Africa [3]. HPV types are defined as distinct variants that have been discovered through several genotypic research. HPV16 (3.2%), HPV18 (1.4%), HPV52 (0.9%), HPV31 (0.8%), and HPV58 (0.7%) are among 5 most common HPV types worldwide [4] as stated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Persistence of infection with HPV high risk types 16 and 18 is responsible for the etiology of cervical cancer in approximately 70% of cases [4].

HPV is a non-enveloped DNA virus, with 8, 000 nucleotides in its genome. There are over 118 HPV types [5, 6], and around 40 different HPVs that can infect the human anogenital mucous membrane [7, 8]. There are a group of HPVs that are referred to as “other high risk” which are defined as those frequently associated with invasive cervical cancer. Moreover, the sum of the supposed high-risk types is 14, and 11 types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, and 58) are constantly classified as high risk [9-11].

The populous sub-Saharan African country Nigeria, has cervical cancer as the second most common cancer (after breast cancer). It is estimated that 14, 550 women are diagnosed with HPV annually [4]. Current estimates show that about 23.7% of women harbor cervical HPV infection and 29.6% have high-grade cervical lesions [5]. Most cases of cancer of the cervix, especially in developing countries, present at advanced stages when curative measures are unlikely to be successful [9]. The incidence of cervical cancer in Nigeria is 25/100,000, and the HPV prevalence in the general population is about 27% [9]. The incidence of HPV in women with cervical cancer is reported to be 24.8% [10]. Out of these, 15 high risk (HR) types cause most cervical cancers.

Even though obstinate HR HPV infection is required to bring about the onset of cervical cancer, only a small proportion of infections progress into disease conditions. Sexually transmitted infections with HPV are common, with about 75% of women experiencing exposure to HPV at a stage in life [10]. However, about 90% of infected women will base a competent immune response, and remove the infection before 2 years without long-term health costs.

Pap smear was the method of choice in the mid-1950s, the main tool to detect early precursors to cervical cancer. However, it needs interpretation by trained pathologists, and is a relatively imprecise test, having a high rate of reporting false negatives [11]. The HPV virus is problematic to culture in vitro, and a demonstrable antibody response has not been seen in all infected patients [12]. Consequently, the introduction of nucleic acid testing by PCR was welcomed as it is a sensitive, minimallyinvasive method for determining the presence of an active cervical HPV infection. The HPV DNA test also has a very high negative predictive value [13].

Vaccines made protect against HPV-cervical cancer are available to an extent. The bivalent vaccine Cervarix®,produced by GlaxoSmithKline (Brentford, UK) for women prevents infection of HPV types 16 and 18 only. However, the women may not be fully immunized because of the presence of other types not covered by the vaccines available [12].

In Nigeria, varied HPV prevalence has been previously reported, which ranged from 10% in Port Harcourt [13], 26.3% in Ibadan [14] to 37% in Abuja [15]. The earliest and most notable was that of Thomas et al. [14] in 2004 at Ibadan. However, fewer have documented the HPV types present in Nigeria. Consequently, the aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of genital HPV infection amongst apparently healthy, sexually active women in Lagos, Nigeria. This is in an effort to guide future vaccination programs in-country.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Type and Ethical Approval

This was a cross-sectional observational study of sexually active women in Lagos state of Nigeria. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research (NIMR), Lagos, Nigeria.

Study Population

One hundred and ninety-eight (198) apparently healthy, sexually active women, visiting various clinics in Lagos metropolis for routine cervical screening tests were screened. The samples were collected between March and July 2014.

Eligibility Criteria and Consent

Samples were collected from consenting females 18 years and above. Two hundred and forty-five (245) women were invited, out of which 198 provided informed consent. For those who were not literate, consent was obtained through interpretation in their local dialect by witnesses.

Exclusion Criteria

Menstruating or pregnant females, and those who have had hysterectomies performed on them were excluded from the study. These factors would have influenced sample collection.

Gynecological Examination and Specimen Collection from Study Subjects

Before obtaining samples, bio data and related information were collected. This included age, marital status, age at first penile-vaginal contact, the number of life time-sexual partners, etc.

Trained health workers collected samples by obtaining high cervical tissue with the aid of brushes (Cervex®, Rovers Medical devices B.V, The Netherlands). Each sample was stirred into a COBAS®PCR cell media vigorously for 10 seconds, to solubilize the sample, sealed and sent to the Centre for Human Virology and Genomics, of NIMR, for analysis. Samples in cell media are stable at 30 ºC for up to 6 months.

Human Papillomavirus Detection

The HPV genotype tests were performed using the automated COBAS®4800 system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The system consists of two instruments, the Cobas X480 and Cobas Z480 instruments, for specimen extraction and detection analysis respectively. The test identifies HPV16, HPV18 and OHR genotypes (consisting of 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68, but reports them as OHR) at clinically relevant infection levels. It consists of two procedures: (1) Automated specimen preparation which extracts HPV and cellular DNA simultaneously; (2) PCR amplification of target DNA sequences using both HPV and β-globin (internal control) specific complementary primer pairs and real-time detection of cleaved fluorescent labelled HPV and β-globin specific oligonucleotide detection probes. The sensitivity and specificity of the assay as stated by the manufacturer were 90% (95% CI: 81.5% to 94.8%) and 70.5% (95% CI: 68.1% to 72.7%) respectively[16].

One milliliter each of the samples were transferred into labelled plain tubes (10 mL) placed on sample racks. The uncapped tubes containing samples and reagents were loaded onto the X480, and the assay process started. After the successful completion of sample preparation, a 96 well plate carrier containing processed samples was manually moved to the Z480 for real time PCR amplification and detection.

Statistical analysis

All results obtained were collated and analyzed using SPSS version 20. Confidence intervals were calculated using STATA version 15.

RESULTS

Socio-demographics and sexual history of participants

Age of the women ranged from 18 to 65 years, with a mean of 34.6 ± 6.4 years, but the majority (41.4%) were between 20 and 39 years. Out of the total (198) studied, 135 (63.2%) women possessed a secondary education, while 50 (23.5%) had a tertiary education. Sixty-five percent (65%) were married, while 30% and 2% were single and divorced respectively (Table 1).

Age at the first penile-vaginal contact ranged from 9 to38 years (mean 20.4 ± 3.9). One hundred and twenty-eight (64.6%) women reported total life-time sexual partners of between 2 and 4 (mean 2.9 ± 2.5) and 69 (34.8%) have had one sexual partner to date of the interview, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 The socio-demographic and sexual history of the study population

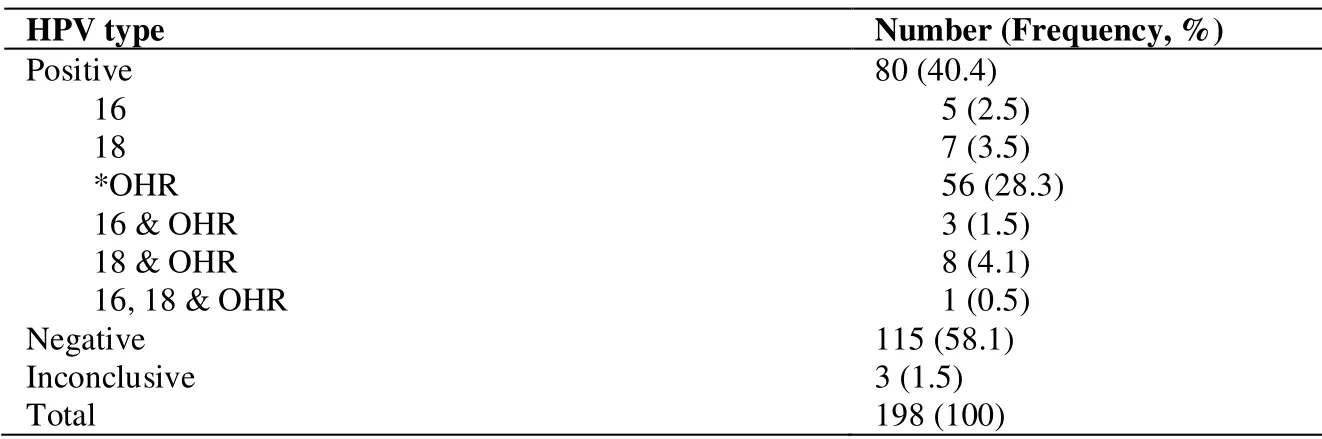

Table 2: The prevalence of HPV types among 198 women in Lagos, Nigeria.

The HPV types

Overall prevalence of high-risk HPV was 40.4% and frequencies of types obtained were as follows: HPV16, 2.5%; HPV18, 3.5%; OHR-HPV, 28.3%; HPV16 and OHR-HPV, 1.5%; HPV18 and OHR-HPV, 4.1%; HPV16, 18 and OHR-HPV, 0.5%. Negative and inconclusive were 58.1% and 1.5% respectively (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Human papillomavirus (HPV) has for some time been recognized as the major progenitor of cervical cancer in women. The prevalence of high-risk HPV estimated from this study (40.4%) is higher than the prevalence previously reported in Lagos (19.6%), Ibadan (18.3%) and Irun, near Ife (14.6%) [14]. The higher prevalence is skewed may be due to the particular cohort studied, and not a varied group of women.

While this study utilized an automated instrument specifically for the detection of HPV (Roche Cobas®4800, Branchburg, The USA), other studies used non-radioactive signal amplification method (Hybrid capture2®, Digene Corp., USA sensitivity/specificity 91.1%/83.7%) and PCR in combination with flow hybridization (Geno Array, Hybribio Biochemical Company Limited, China sensitivity/specificity 97.8%/100%). Different assays have variations in their ability to detect HPV types due to their varied analytical sensitivities and specificities [13].

The prevalence of 12 OHR-HPV (28.3%) (31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66 and 68) in this study was similar to that observed in the study by Clifford et al. [17] (25.6%) and also that of West African immigrants in Italy (35.5%) [18]. These research findings agree with the study by Ngandwe et al. that in sub-Saharan Africa, other HR types may be a strong factor in cervical cancer progression than previously believed [21]. However, this study resulted in a prevalence of HPV 16 and 18 (2.5% and 3.5% respectively) similar to the global prevalence [22-24].

There was a fairly large proportion (63.2%) of the study population with at least a secondary basic educational level. This presupposes that they would be knowledgeable enough to seek health interventions when needed. There were more married women in the study population (65.1%), suggesting such group of the society is likely more concerned about their sexual health than the single, divorced, widowed and separated.

There could be severe implications of these OHR HPVs to vaccine administration in the region. This is due to the fact that they are type specific (divalent or tetravalent), signifying the current vaccines may not be as effective as projected in the sub-Saharan Africa region [17]. Preceding studies from sub-Saharan Africa illustrate that although the burden of HPV is high compared to Western regions (Europe and North America), a lower prevalence of HPV 16 and 18 and a higher prevalence of OHR HPV such as HPV 31, 35 and 58, were observed [16]. Additionally, in a similar Ecuadorian study, types 16 and 18 were also the most frequent, for both simple (47.3% and 15.5%, respectively) and multiple infections (57.1% and 54.2%, respectively). Genotype 58 was the third most common in simple infections (10%), while 51 ranked third in multiple infections (42.9%) [17, 18].

Current vaccination efforts in Nigeria are far from adequate as coverage is very low [14, 25, 26]. Nigeria lacks effective vaccination coverage system, infrastructure and policy, for proper delivery of much needed vaccines. The country also lacks proper cold-chain systems for vaccine preservation [16]. Nigerian health workers have highlighted barriers to HPV vaccination which include lack of awareness, vaccine availability and its accessibility, cost, and concerns about acceptability [27]. It is hoped that these would improve in the nearest future. Prevention strategies if properly implemented in both developed and developing countries, thousands of lives could be saved [18].

Study Limitations

The study enrolled sexually active women only, which may have biased the HPV types obtained. This group of women are usually the most aware of the HPV and willing to give such samples. The maternal stage in which most are in encourages them to seek medical interventions to improve health.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study presents a high prevalence (28.3%) of OHR HPV types in sexually active Nigerian women. Findings from this research will impact and influence the immunization choice policy of the country as existing HPV vaccines only cover HPV-16 and HPV-18. The findings are further contributive evidence to the initiative to eradicate cervical cancer as a public health challenge in Nigeria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Roche Diagnostics Nigeria, for the kind donation of the COBAS 4800 system instruments, and also the starter kits used for this study to NIMR.

Author contributions:Okwuraiwe AP performed the laboratory analysis, did statistical analysis and wrote the draft manuscript. Gbajabiamila TA and Idigbe IE collected cervical tissue samples from study participants. Audu RA was responsible for the design, logistics for laboratory testing and contributed in manuscript preparation. Ezechi OC conceived the idea and contributed in the final version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests:The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Citation:Okwuraiwe AP, Audu RA, Gbajabiamila TA, Idigbe IE, Ezechi OC. HPV prevalent types in a cohort of sexually active Nigerian women: implications for vaccination programmes. Precision Medicine Research. 2021;3(3):12. doi: 10.53388/PMR2021061101.

Executive editor:Na Liu, Jin-Feng Liu.

Submitted:11 June 2021,Accepted:23 August 2021,Online:25 August 2021

© 2021 By Authors. Published by TMR Publishing Group Limited. This is an open access article under the CC-BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/BY/4.0/)