Cytotoxic effects of Thai noni juice product ethanolic extracts against cholangiocarcinoma cell lines

Jeerati Prompipak, Thanaset Senawong,2, Banchob Sripa, Prasan Swatsitang, Paweena Wongphakham, Gulsiri Senawong✉

1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

2Natural Product Research Unit, Faculty of Science, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

3Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen 40002, Thailand

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Antiproliferation; Apoptosis; Bile duct cancer;Cholangiocarcinoma; Morinda citrifolia L.; Noni; Oxidative stress;Reactive oxygen species; ERK

1. Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is an adenocarcinoma arising from the bile duct epithelium cells. The incidence and mortality rates of CCA in Thailand, especially in the northeastern region, have been documented as the highest in the world[1]. The main risk factor of CCA in Thailand is infection by a carcinogenic liver fluke,Opisthorchis viverrini. However, primary sclerosing cholangitis,hepatolithiasis, choledochal cysts, and congenital bile duct anomalies have been reported as CCA associated risk factors[2].The anticancer drugs, 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, and gemcitabine,have been used for CCA treatment[3], but the clinical chemotherapy of CCA patients is limited due to multiple side effects. Therefore,finding new drugs with low toxicity is still needed and alternative medicine with herbal plants has been of intense interest as anti-CCA agents in combination therapy with the anticancer drug treatments.

Noni (Morinda citrifolia L.), known as Yor in Thailand, is a traditional plant in tropical countries belonging to the family Rubiaceae. Several parts of noni have been used as a medicinal herb with pharmacological properties including antioxidant, antimicrobial,anti-inflammatory, anti-arthritic, and anticancer[4]. In the early 1990s, noni fruit juice had become available as commercial products in the USA. To date, noni juice products have been globally used as dietary supplements and herbal drinks, which have been accepted in the European Union as a novel food since 2002[5]. Several studies have revealed that noni juice possessed anticancer activity, e.g. noni juice from Health India Laboratories (Noni Biotech Pvt. Ltd., India)inhibited the growth of cervical cancer cell lines (HeLa and SiHa)through induction of intrinsic apoptotic pathways[6]. Subsequently,Ali and co-worker reported that the noni juice of ripe noni fruits from Noni Biotech Pvt. Ltd. enhanced anti-tumor and reduced toxicity of cisplatin on Ehrlich ascites carcinoma bearing mice[7]. A number of bioactive compounds in noni juice have been identified,including phenolic acids (p-hydroxybenzoic, p-coumaric, ferulic, and sinapic acids), flavonoids (rutin, quercetin, and kaempferol), iridoids(asperulosidic and deacetylasperulosidic acids), and coumarins(scopoletin)[8]. Phenolic acids are phytochemicals distributed as secondary metabolites in the plant kingdom. Although phenolic acids basically act as antioxidant agents, under certain conditions,they promote the death of cancer cells through reactive oxygen species (ROS) induction[9]. An imbalance of the cellular ROS causes oxidative stress that induces apoptosis through the endoplasmic reticulum pathway via the disruption of protein folding and the reduction of stored calcium in the endoplasmic reticulum[10].Moreover, ROS induces apoptosis through a mitochondrial pathway via the disruption of a mitochondrial membrane, which causes cytochrome C release and activation of apoptotic signaling cascades[11].

At present, several brands of Thai noni juice (TNJ) products in Thailand are popularly consumed as herbal drinks that are distributed as local products as well as being commercialized worldwide.Although the TNJ products have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration of Thailand, their phytochemical composition,anti-cancer activity, and toxicity have not yet been reported. From our preliminary research, eight commercial TNJ products in Thailand have been studied and two of them [Thai noni juice Chiangrai (TNJCr) and Thai noni juice Buasri (TNJ-Bs)] exhibited promising antiproliferative activities against colon, cervical, and breast cancer cell lines (Senawong et al., unpublished data). Therefore, the potential anti-CCA properties and toxicity of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs need to be evaluated. In this study, the ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs products were further investigated for the mechanism(s) underlying their anti-CCA effects and their toxicity on non-cancerous human bile duct epithelial cells and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The phenolic acid profiles of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs products were also determined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

The commercial TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs used in this study were purchased from the market and the same lot number was used throughout the study. Phenolic acid standards were purchased from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO,USA), and Acros Organic (Geel, Belgium). Ficoll-PaquePLUS was purchased from BD Healthcare (Uppsala, Sweden). Annexin V- FITC apoptosis detection kit and propidium iodide (PI) were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively. The antibodies against p53 (#2524), Bax (#2772), Bcl-2 (#2870), pERK1/2 (#4377), and ERK1/2 (#9107) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology(Beverly, MA, USA) and 2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFHDA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Cell lines and cell culture

CCA cell lines, KKU-100 (poorly differentiated) and KKU-213B (well differentiated), established from primary tumors of opisthorchiasis-associated Thai CCA patients, were kindly provided by Dr. Banchob Sripa (Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand).The H69 human bile duct epithelial cell line was a kind gift from Dr. D.Jefferson (Tufts University, Boston, MA, USA). All the cell lines were cultured and maintained as previously described[12].

2.3. Preparation of TNJ ethanolic extracts

The 60 mL of TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs products were extracted by stirring continuously with 140 mL of absolute ethanol for 4 h at room temperature before filtering through No.1 Whatman filter papers and concentrating the filtrates by rotary evaporator. The remaining filtrates of TNJ ethanolic extracts were freeze-dried and stored at -20℃ until further used for cell treatments. Extractions of free and esterified phenolic acids of the ethanolic extracts of TNJCr and TNJ-Bs were processed by the method of Senawong et al.[13]and then suspended in 1 mL of 50% methanol (HPLC grade) (v/v) before filtering through 0.2 μm pore size of syringe filter. The free and esterified phenolic acids of ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs were analyzed for the total phenolic contents and the phenolic acid compositions by the Folin-Ciocalteu method and HPLC analysis, respectively.

2.4. Total phenolic contents of TNJ ethanolic extracts

Folin-Ciocalteu method was used to determine the total phenolic contents of TNJ ethanolic extracts as previously described[14].Briefly, the free and esterified phenolic acids of ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs were diluted with 50% methanol to several concentrations (100%, 50%, 25% v/v). After that, 250 μL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent was added to each sample followed by adding 750 μL of 20% sodium carbonate solution. The sample volume was adjusted to 5 mL by adding distilled water and further incubated at 50 ℃ for 2 h. After incubation, samples were immediately measured for absorbance at 765 nm. Total phenolic content was calculated from a standard curve of gallic acid and the final results were presented as μg gallic acid equivalent per mL of TNJ products.

2.5. Phenolic acid compositions of TNJ ethanolic extracts

To identify the phenolic acid composition of TNJ ethanolic extracts,the free and esterified phenolic acids of ethanolic extracts of TNJCr and TNJ-Bs were determined by HPLC (1260 DAD Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a reversed-phase C18 column (InertsilODS-4, 5 μm particle diameter, 4.6 mm×250 mm). The column temperature was maintained at 25 ℃. The compounds were separated by gradient elution of 100% acetonitrile and 1% acetic acid in deionized water with the flow rate of the mobile phase 1.0 mL/min. The phenolic acids were detected by a diode array detector at the wavelength of 280 nm. Based on peak areas, the concentration of individual phenolic acids was analyzed by using a standard curve with the internal standard of m-hydroxybenzaldehyde.

2.6. Cell viability assay

Colorimetric 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was used to determine the viability of cells. Cells were cultured at a density of 8×10cells per well in 96-well plates for 24 h and then treated with solvent [0.5% ethanol + 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); solvent control] and various concentrations of TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts (0.5-4.0 mg/mL) for 24, 48 and 72 h. After that, the culture medium was removed and cells were incubated with a fresh medium containing MTT for 2 h at 37 ℃.DMSO was added and the absorbance (A) was measured at 550 nm by an EZ read 2000 microplate reader (Biochrom, Cambridge,UK) with the absorbance at 655 nm as a reference wavelength. Cell viability was determined and presented as a percentage using the following equation: % cell viability = [(A550 sample-A655 sample)/ (A550 control-A655 control)] ×100.

2.7. Isolation of human PBMCs and trypan blue dye exclusion assay

PBMCs were isolated from the blood of healthy volunteers (25-30 years old) who did not smoke, drink alcohol and take any drug in the last one month. PBMCs were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-PaquePLUS, following the manufacturer’s instructions. PBMCs were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 2×10cells per well with RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS and antibiotics for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with solvent (0.5% ethanol + 0.5% DMSO; solvent control) and ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs (2.0 and 4.0 mg/mL) for 24 h. PBMCs were collected and mixed with an equal volume of 0.4% trypan blue dye solution. The number of viable cells was directly observed and counted by using a hemocytometer through a phase-contrast microscope. Percentage of cell viability was calculated and compared with solvent control.

2.8. Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle phase distribution was analyzed by using PI staining and flow cytometry. Cells were cultured in 5.5 cm dish plate at a density of 1×10for 24 h and then treated with solvent (0.25% ethanol +0.25% DMSO) and various concentrations of TNJ-Cr (0.75-3.00 mg/mL) or TNJ-Bs (2.00-4.50 mg/mL) ethanolic extracts for 24 h.After that, cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1% glucose, and fixed in 70% ethanol for 1 h on ice. The fixed cells were washed with PBS and incubated with RNase A (0.1 mg/mL) at 37 ℃ for 30 min. To stain the DNA content in each cell, PI (40 μg/mL) was added and incubated for 45 min at room temperature. Stained cells were analyzed by a flow cytometer(BD FACSCantoⅡ, Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) to determine the cell cycle phase. The number of cells in sub-G, G/G,S, and G/M phases was analyzed and presented as the percentage using BD FACSDiva™ software serviced by Research Instrument Center, Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

2.9. Apoptosis assay

Detection of apoptotic cells was performed using annexin V-FITC and PI staining (Annexin V-FITC, BioLegend, San Diego, CA)according to the manufacturer’s instructions and analyzed by flow cytometry. Briefly, cells were seeded in a 5.5 cm dish at the density of 1×10and cultured for 24 h before treating with solvent (0.25%ethanol + 0.25% DMSO) and various concentrations of TNJ-Cr(0.75-3.00 mg/mL) or TNJ-Bs (2.00-4.50 mg/mL) ethanolic extracts for 24 h. After that, cells were collected, washed with cold PBS,resuspended with annexin V-binding buffer, and then stained with annexin V-FITC and PI in the dark for 15 min at room temperature.Apoptotic cells were analyzed by BD FACSCantoⅡ Flow Cytometer and BD FACSDiva™ software.

2.10. Western blot analysis

Cells (1×10cells/dish) were seeded and cultured in a 5.5 cm dish before treatment with solvent (0.25% ethanol + 0.25% DMSO)and various concentrations of TNJ-Cr (0.75-3.00 mg/mL) or TNJBs (2.00-4.50 mg/mL) ethanolic extracts for 24 h. Then, cells were lysed with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail(AMRESCO, Inc., Ohio, USA) and the total cellular proteins were determined by using Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). An equal amount of protein in each condition was separated by 12.5%SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane.The membranes were then blocked with 3% skim milk in PBS-T for 1 h, then incubated with primary antibody against p53 (diluted 1:1 000), Bcl-2 (diluted 1:1 000), Bax (diluted 1:1 000), pERK1/2(diluted 1:1 000), or ERK1/2 (diluted 1:2 000) at 4 ℃ overnight,washed with PBS-T, subsequently incubated with anti-mouse or antirabbit conjugated horseradish peroxidase secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature and washed again before developing with an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). The immunoreactive bands were exposed to X-ray film and the relative protein intensity was analyzed by ImageJ program using the total ERK1/2 as loading control.

2.11. Detection of intracellular ROS

The intracellular ROS level was measured by using a cellpermeable probe DCFH-DA. Cells were seeded and cultured for 24 h in a 5.5 cm dish at a density of 1×10cells per dish before treatment with solvent (0.25% ethanol + 0.25% DMSO) and various concentrations of TNJ-Cr (0.75-3.00 mg/mL) or TNJ-Bs (2.00-4.50 mg/mL) ethanolic extracts for 24 h. Cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed with PBS, resuspended in PBS, and incubated with 20 μM DCFH-DA at 37 ℃ for 30 min. After washing cells twice with PBS, dichlorofluorescein in cells was immediately measured by a flow cytometer. The intensity of dichlorofluorescein is proportional to the amount of ROS and the level of ROS was presented as the percentage relative to solvent control.

2.12. Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed by using IBM SPSS version 19.0 for windows (SPSS Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to calculate statistical significance between the treated groups and solvent control group. The statistical significance of different groups was considered at P<0.05.

2.13. Ethical statement

The experimental protocols have been reviewed by Khon Kaen University Ethics Committee for Human Research based on the Declaration of Helsinki and the ICH Good Clinical Practice Guidelines (in order of 3.4.01: 01/2020 No. HE622245).

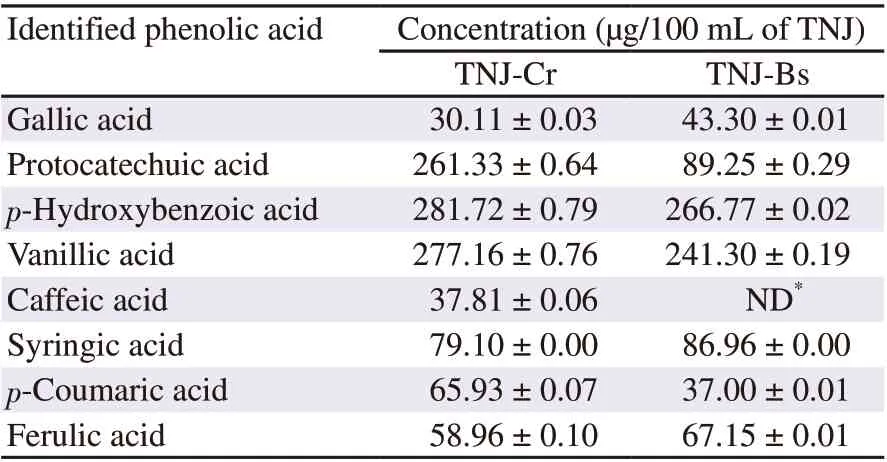

Table 1. Phenolic acid compositions of TNJ ethanolic extracts.

3. Results

3.1. Phenolic contents and phenolic acid compositions of TNJ products

Total phenolic contents of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method were (1 528.66 ± 117.98)and (433.33 ± 104.07) μg gallic acid equivalents per mL of TNJ products, respectively. Phenolic acid compositions in TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts were determined by HPLC. The phenolic acids of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts included gallic,protocatechuic, p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, syringic, p-coumaric,and ferulic acids, as shown in Figure 1B and 1C, respectively. The phenolic acids were identified by comparing their retention time and spectrum with those of the phenolic acid standards (Figure 1A). Caffeic acid was identified only in TNJ-Cr ethanolic extract.The phenolic acid concentrations in TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts are summarized in Table 1. The major phenolic acids in ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr were p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, and protocatechuic acids and of TNJ-Bs were p-hydroxybenzoic and vanillic acids.

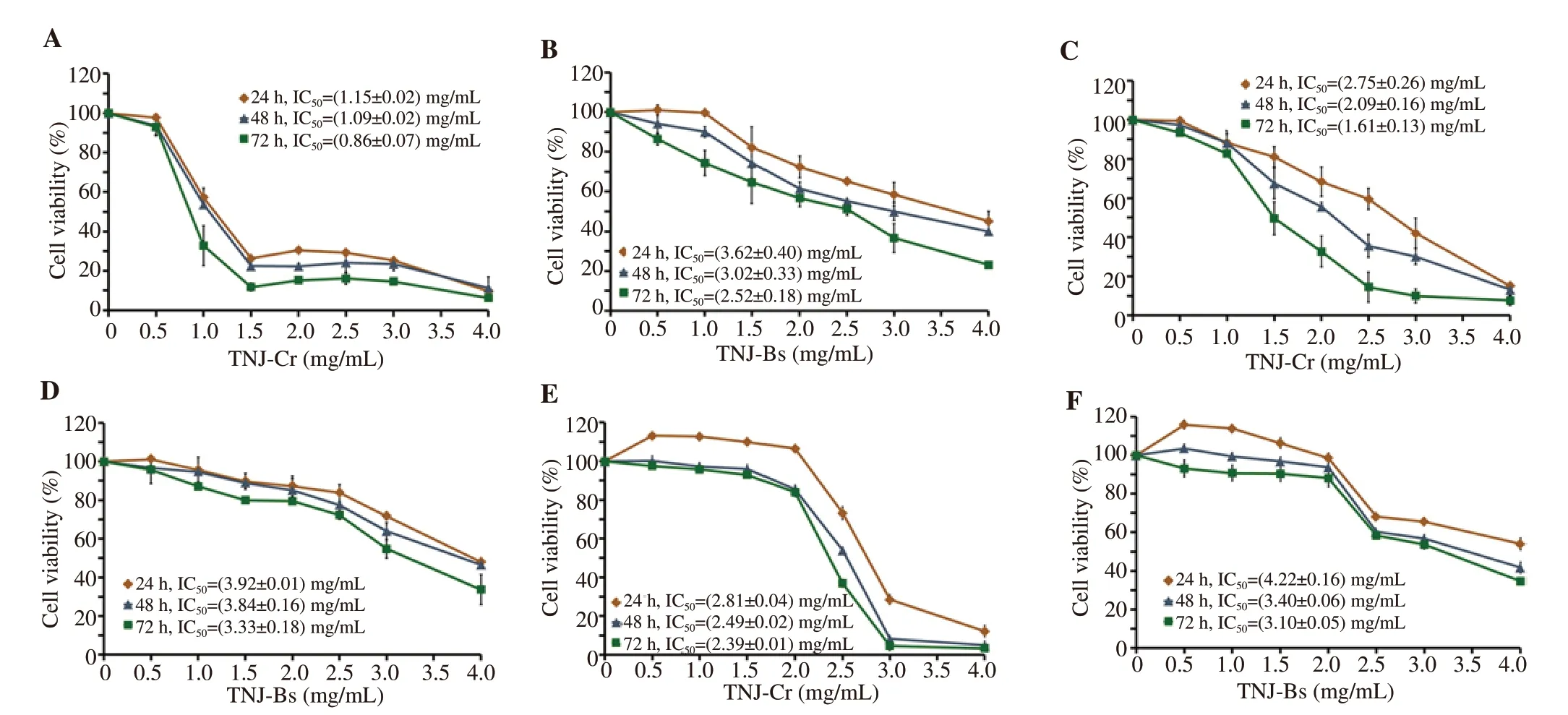

3.2. Cytotoxic effect of TNJ ethanolic extracts

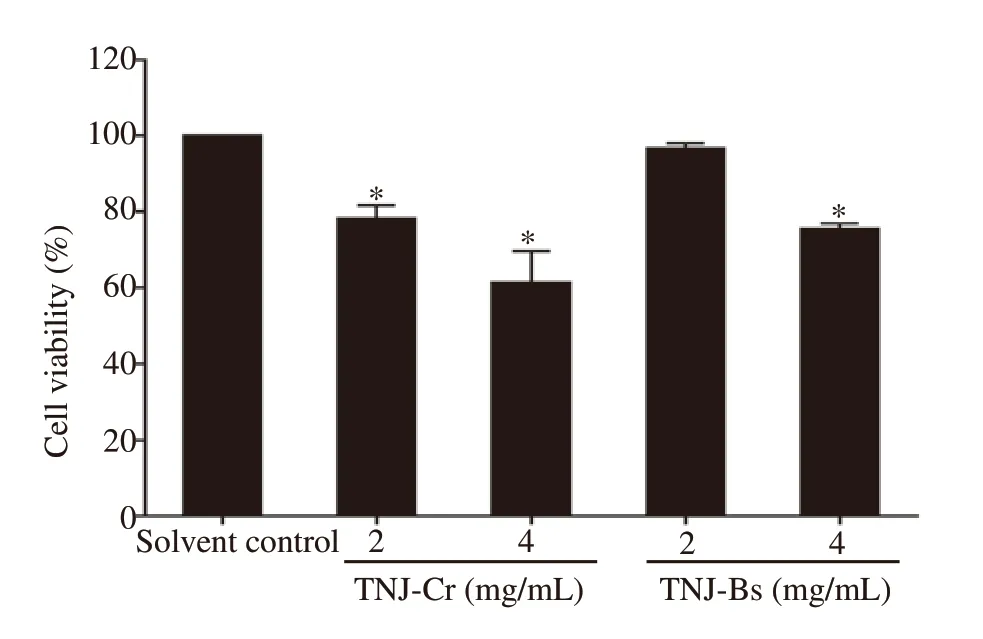

To evaluate the toxicity of TNJ ethanolic extracts against cancer and non-cancer cells, MTT and trypan blue dye exclusion assays were used to determine the viability of cancer and non-cancer cells (PBMCs), respectively. MTT assay results showed that TNJ ethanolic extracts decreased cancer cell viability in a dose- and timedependent manner (Figure 2). The cellular sensitivity for each TNJ ethanolic extract was determined by ICvalues. The ICvalues of TNJ-Cr ethanolic extract against KKU-100 (Figure 2A) and KKU-213B (Figure 2C) for 24 h were (1.15 ± 0.02) mg/mL and (2.75± 0.26) mg/mL, respectively. Whereas the ICvalues of TNJ-Bs ethanolic extract against KKU-100 (Figure 2B) and KKU-213B(Figure 2D) at 24 h exposure, were (3.62 ± 0.40) and (3.92 ± 0.01)mg/mL, respectively. Based on the ICvalues, KKU-100 cells were more responsive to both TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts than KKU-213B cells. In addition, the ICvalues of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts against non-cancer H69 cells at 24 h were (2.81± 0.04) and (4.22 ± 0.16) mg/mL, respectively (Figure 2E and 2F).This result implied that non-cancer H69 cell line was also sensitive to both TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts. However, KKU-100 cell line was more sensitive to the exposure of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts at 24, 48, and 72 h than H69 cells. Moreover, the ICvalues of TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts against normal cells (PBMCs) (Figure 3) after treatment for 24 h were more than 4.0 mg/mL indicating lower toxicity of TNJ ethanolic extracts to normal cells.

Figure 1. Chromatograms of phenolic acid standards (A), ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr (B) and TNJ-Bs (C), which 1 = Gallic acid, 2 = Protocatechuic acid, 3 = p-Hydroxybenzoic acid, 4 = Vanillic acid, 5 = Caffeic acid, 6 = Syringic acid, 7 = p-Coumaric acid, 8 = Ferulic acid, 9 = Sinapinic acid.m-Hydroxybenzaldehyde was used as an internal standard (IS).

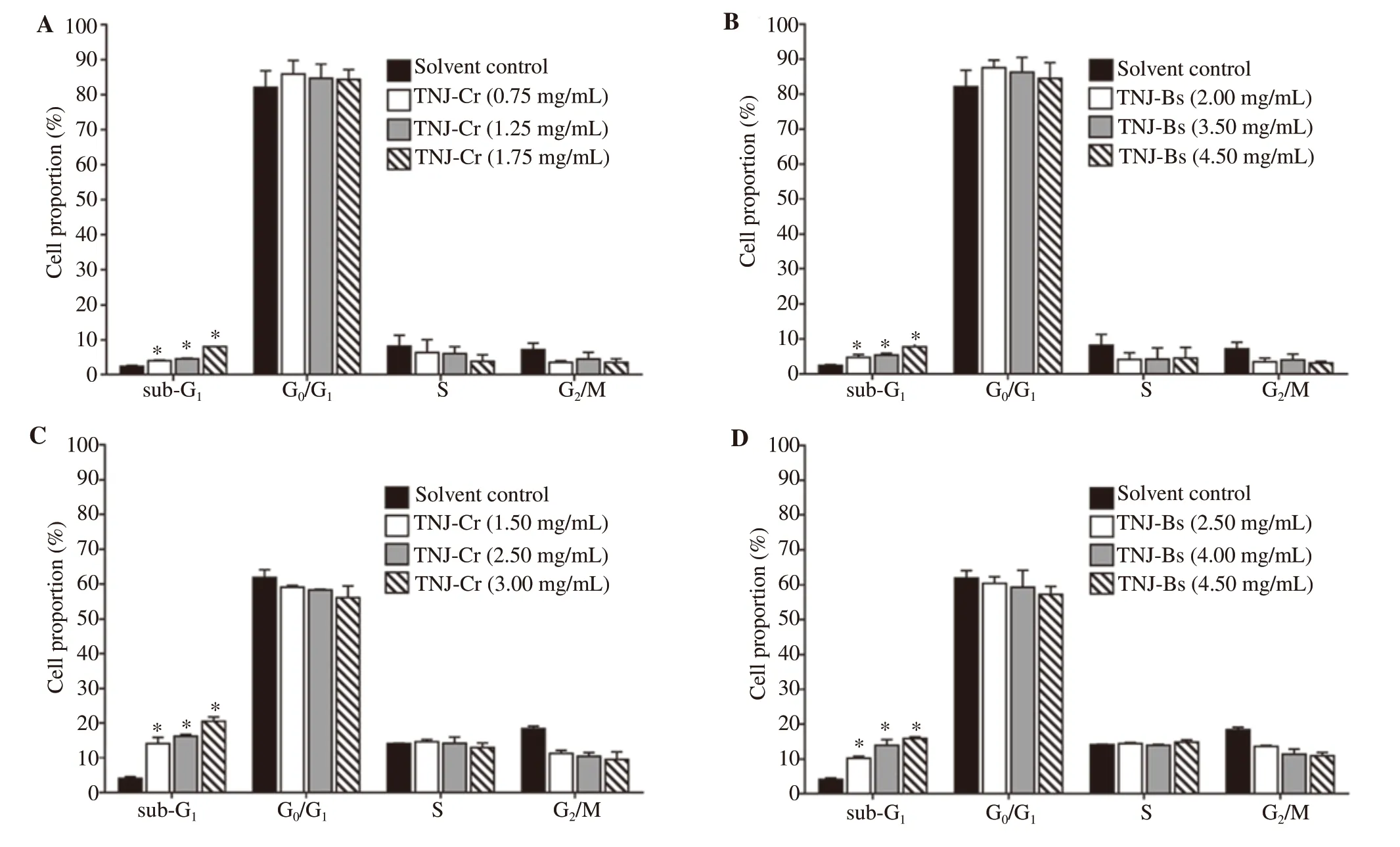

3.3. Effect of TNJ ethanolic extracts on cell cycle distribution

To reveal the mechanism underlying the antiproliferative effects of TNJ ethanolic extracts, the cell cycle progression was determined by using PI staining and flow cytometry. Using the inhibitory concentration (IC) values, KKU-100 and KKU-213B cells were treated with various concentrations of TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts for 24 h. In Figure 4, the concentrations of TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts did not cause cell cycle arrest in both KKU-100 (Figure 4A and 4B) and KKU-213B (Figure 4C and 4D)cells, however, the percentages of cell populations in sub-Gwere increased indicating that the TNJ ethanolic extracts may induce apoptosis in CCA cells.

Figure 2. Cytotoxic effect of TNJ ethanolic extracts on CCA cell lines, KKU-100 (A, B) and KKU-213B (C, D), and non-cancer H69 cells (E, F). Cells were treated with TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts ranging from 0-4 mg/mL for 24, 48, and 72 h. The percentage of cell viability was calculated by comparing it with the solvent control (0.5% ethanol + 0.5% DMSO). The data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Figure 3. Cytotoxic effect of TNJ ethanolic extracts on the normal cells,PBMCs, at 24 h of treatment. Cells were incubated with 2.0 and 4.0 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts. The percentage of cell viability was calculated by comparing it with the solvent control (0.5% ethanol +0.5% DMSO). The data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P<0.05 versus solvent control.

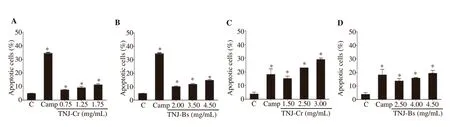

3.4. Apoptosis induction by TNJ ethanolic extracts

Based on the increases of sub-Gpopulation, annexin V-FITC and PI staining were used to determine apoptosis induction by TNJ ethanolic extracts in CCA cell lines after 24 h exposure. The percentages of apoptotic cells were significantly increased in KKU-100 (Figure 5A and 5B) and KKU-213B (Figure 5C and 5D) cells when treated with ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs. In addition, both TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts caused a higher percentage of apoptotic cells in KKU-213B compared to KKU-100 cells. Moreover, the highest concentration of TNJ-Cr ethanolic extract (3.00 mg/mL) could induce greater levels of apoptosis in KKU-213B cells than the positive control camptothecin (25 μg/mL).

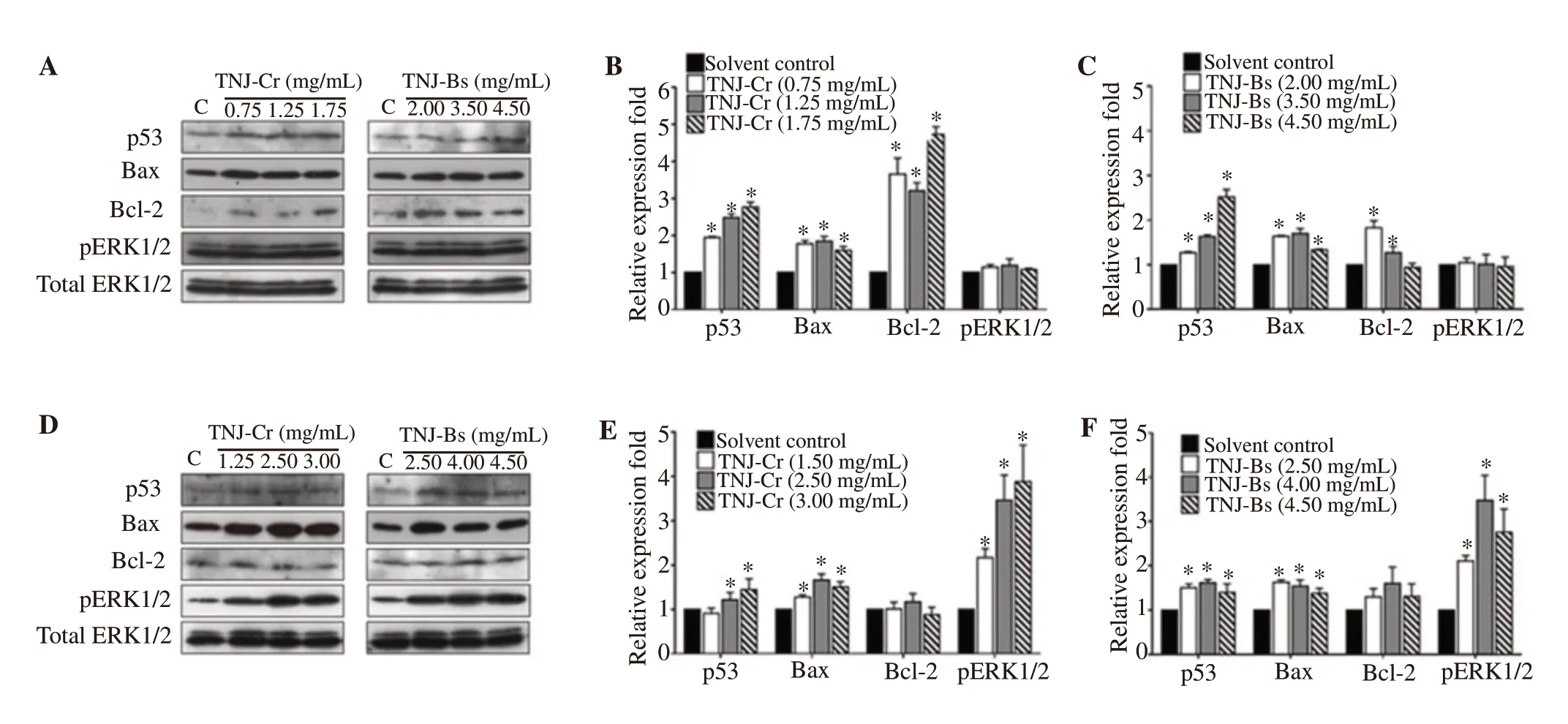

3.5. Effect of TNJ ethanolic extracts on proteins related to apoptosis and ERK signaling

To identify the molecular mechanisms of TNJ ethanolic extracts for inducing apoptosis of CCA cell lines, the expression levels of proteins known for apoptosis and ERK signaling such as p53, Bax,Bcl-2, and pERK1/2 were determined by Western blot analysis. In KKU-100 cells, the expression levels of p53, Bax, and Bcl-2 were increased after exposure to TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts(Figure 6A-6C). In KKU-213B cells, up-regulation of p53 and Bax was observed when treated with TNJ-Cr or TNJ-Bs ethanolic extracts (Figure 6D-6F), while the expression level of Bcl-2 showed no significant change. Moreover, the expression level of pERK1/2 was up-regulated in KKU-213B (Figure 6D-6F) but not in KKU-100(Figure 6A-6C) cells when exposed to both TNJ ethanolic extracts.

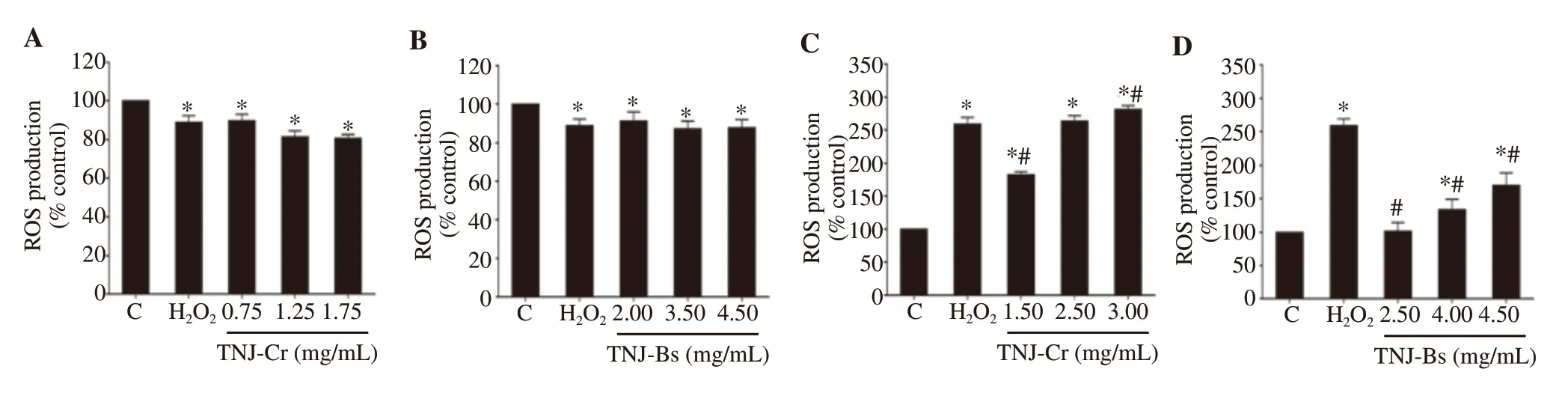

3.6. Intracellular ROS generation

To determine whether TNJ ethanolic extracts induced apoptosis through oxidative stress, the intracellular ROS in CCA cells treated with TNJ ethanolic extracts was detected by DCFH-DA staining and flow cytometry (Figure 7). In KKU-100 cells, both TNJ ethanolic extracts did not increase the generation of ROS (Figure 7A and 7B),while in KKU-213B cells, the ROS level was significantly increased responding to both TNJ ethanolic extracts compared with solvent control (Figure 7C and 7D). The highest concentration of TNJCr ethanolic extract caused a significantly greater amount of ROS production than the 300 μM HOpositive control.

Figure 4. Effects of TNJ ethanolic extracts on cell cycle distribution in KKU-100 (A, B) and KKU-213B (C, D) cells at 24 h of treatment. KKU-100 cells were treated with 0.75, 1.25, 1.75 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.00, 3.50, 4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs. KKU-213B cells were treated with 1.50, 2.50, 3.00 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.50, 4.00, 4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs. The percentage of cell populations in each cell cycle phase was shown as bar graphs of mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P<0.05 versus solvent control.

Figure 5. Apoptosis induction on KKU-100 and KKU-213B cells at 24 h after exposure to TNJ ethanolic extracts. KKU-100 cells were treated with 0.75,1.25, 1.75 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.00, 3.50, 4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs. KKU-213B cells were treated with 1.50, 2.50, 3.00 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.50, 4.00,4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs. Bar graph shows the mean of the percentage of apoptotic KKU-100 (A, B) and KKU-213B (C, D) cells from three independent experiments. C: solvent control; Camp: Camptothecin 25 μg/mL was used as a positive control. *P<0.05 versus solvent control.

4. Discussion

Figure 6. Western blot analysis of proteins related to apoptosis and ERK signaling after exposure of KKU-100 (A, B, and C) and KKU-213B (D, E, and F) cells to TNJ ethanolic extracts for 24 h. KKU-100 cells were treated with 0.75, 1.25, 1.75 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.00, 3.50, 4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs.KKU-213B cells were treated with 1.50, 2.50, 3.00 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.50, 4.00, 4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs. Total ERK1/2 was used as a loading control.The relative fold of protein expression was shown as relative intensity of the protein band compared to loading control. C: control. *P<0.05 versus solvent control.

Figure 7. ROS production of KKU-100 (A, B) and KKU-213B (C, D) cells after treatment with TNJ ethanolic extracts for 24 h. Bar graph shows the mean of the percentage of ROS generation compared to solvent control (0.25% ethanol + 0.25% DMSO) from three independent experiments. KKU-100 cells were treated with 0.75, 1.25, 1.75 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.00, 3.50, 4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs. KKU-213B cells were treated with 1.50, 2.50, 3.00 mg/mL of TNJ-Cr and 2.50, 4.00, 4.50 mg/mL of TNJ-Bs. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (300 μM) was used as a positive control. C: solvent control. *P<0.05 versus solvent control, #P<0.05 versus positive control.

Two of eight commercial TNJ products approved by the FDA of Thailand, TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs, exhibited anti-proliferative activity against colon, cervical, and breast cancer cells in a screening test(Senawong et al., unpublished data). However, their anticancer activity against CCA cells, phytochemical composition, and toxicity against normal cells had not been reported previously. In this study,the TNJ-Cr and TNJ-Bs phenolic profiles, the in vitro anticancer activity against two CCA cell lines, and the toxicity against non-cancer cells and normal human PBMCs were investigated.Phenolic profiles of both TNJ ethanolic extracts included gallic,protocatechuic, p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, syringic, p-coumaric,and ferulic acids, in which the major phenolic acids were p-hydroxybenzoic, vanillic, and protocatechuic acids. Caffeic acid was identified only in the TNJ-Cr ethanolic extract. Similar to our finding, gallic, p-hydroxybenzoic, caffeic, and ferulic acids were found in noni fruit juice from Taiwan[15], protocatechuic and vanillic acids were identified in ethyl acetate extracts of Costa Rican noni juice[16] and p-hydroxybenzoic, p-coumaric, and ferulic acids were identified in the methanolic extract of the Mexican noni juice and noni bagasse[8]. Both TNJ ethanolic extracts, rich in phenolic content,possess anti-cancer activity against the studied CCA cell lines, the poorly differentiated KKU-100 and well-differentiated KKU-213B cells. The ICvalues illustrated that the TNJ-Cr ethanolic extract possessed greater anti-CCA activity for both KKU-100 and KKU-213B cells. The greater toxicity may be due to the larger amount of total phenolic content. The greater anticancer activity of TNJCr over TNJ-Bs may also be related to the differences in their noni juice manufacturing processes, which include additional ingredients.For example, TNJ-Cr product contains honey while TNJ-Bs is 100% noni juice. The phenolic compounds found in honey were 2-cis, 4-trans abscisic, 2-hydroxycinnamic, caffeic, chlorogenic,cinnamic, ellagic, ferulic, gallic, p-coumaric, p-hydroxybenzoic,protocatechuic, sinapic, syringic, and vanillic acids[17]. In the present study, the caffeic acid found only in TNJ-Cr ethanolic extract might originate from the supplemented honey. A previous study reported that gallic acid inhibited the growth of liver cancer cells (HepG2 and SMMC-7721) through a mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis pathway[18]. Protocatechuic acid prevented the growth of breast (MCF-7), lung (A549), liver (HepG2), prostate (LNCaP),and cervical (HeLa) cancers through induction of apoptosis[19].Derivatives of p-hydroxybenzoic acid acting as histone deacetylase inhibitors inhibited the growth of leukemia K-562 cells[20]. Vanillic acid attenuated the proliferation of breast (MDA-MB-231), liver(HepG2), colorectal (HT-29 and HCT116), nasopharyngeal (CNE-1 and HK-1), cervical (HeLa), ovarian (Caov-3), and leukemia (K562 and CEM-SS) cancers[21]. Syringic acid was shown to prevent the growth of colorectal cancer (SW1116 and SW837)[22]. p-Coumaric acid was shown to suppress the growth of breast (T-47D), colorectal(SW 620), lung (A549), and liver (Hep G2) cancers[23]. Ferulic acid was reported to inhibit the cervical cancer cells (HeLa and CaSki)through cell cycle arrest and autophagy induction[24]. Caffeic acid was shown to enhance the ROS level and oxidative stress which suppressed the growth of human HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells[25].Therefore, the antiproliferative activity of TNJ ethanolic extracts on CCA cells was probably due to the combination of these phenolic acids. However, the existence of promising active compounds in TNJ ethanolic extracts should be further investigated.

In this study, apoptosis but not cell cycle arrest was a mechanism underlying the anti-CCA activity of TNJ ethanolic extracts. Our results demonstrated the TNJ ethanolic extracts induced apoptosis of CCA cells by up-regulating the expression of Bax through a p53-dependent mechanism similar to that of the noni juice from Health India Laboratories, both alone or in combination with cisplatin,increasing the expression of p53 and Bax in HeLa and SiHa cervical cancer cells[6]. In addition, the TNJ ethanolic extracts increased the level of pERK1/2 only in the KKU-213B cells. The activation of ERK1/2 signaling pathway is a known response for apoptosis induction through ROS production[26]. Furthermore, the ethanolic extract of TNJ-Cr could induce ROS generation to a greater extent than TNJ-Bs, which may be due to the presence of caffeic acid from the supplemented honey[25] or the greater amount of total phenolic content. Conversely, KKU-100 cells treated with TNJ ethanolic extracts did not show ROS generation. This cell line is considered to be a drug-resistant cell line that up-regulates the anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2 to overcome drug-induced oxidative stress[27-29].Therefore, the anti-CCA activity of TNJ ethanolic extracts against KKU-100 cells would not appear to involve ROS production.

The cytotoxic effects of TNJ ethanolic extracts on non-cancer(H69) and normal (PBMCs) cells revealed that both TNJ ethanolic extracts were toxic to H69 cells but not toxic to the normal PBMCs.H69 cells, lacking telomerase activity, might be predisposed to senescence and consequently be more sensitive to the treatment after several sub-passages[30]. The recommended dose of TNJ product consumption was 60 mL per day, however, the toxicity in animal and clinical studies remains to be investigated. The Tahitian noni juice with a concentration of 3% in culture medium showed no toxicity in rat hepatoma cells and a clinical trial revealed that drinking up to 750 mL per day of Tahitian noni juice is safe[31,32]. Hence, the anticancer effects and toxicity of TNJ products in animal models and clinical trials should be further studied.

In summary, both TNJ ethanolic extracts inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis of the CCA cell lines by up-regulating Bax and p53. However, the ethanolic extracts of TNJ-Cr exhibited greater anti-CCA activity than that of TNJ-Bs against KKU-100 and KKU-213B cells, which may be due to its greater amount of total phenolic content. Our findings demonstrated that the amount and type of phenolic acids in TNJ ethanolic extracts may be related to their potential anticancer activity. Our data provide evidence that TNJ ethanolic extracts are not toxic to normal human PBMCs. Therefore,the TNJ ethanolic extracts show promise for use in combination therapies with chemotherapeutic drugs for the treatment of CCA.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Graduate school, Khon Kaen University, Thailand for providing a graduate scholarship to Miss Jeerati Prompipak(591T221). We would like to thank Associate Professor Dr. Albert J.Ketterman, Mahidol University, Thailand, for English proofreading.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand through Khon Kaen University, granted number 592302 and 601702.

Authors’ contributions

GS contributed to concept, designed experiment, analyzed data,wrote and edited the manuscript. JP performed the experiment,analyzed data, and also contributed to manuscript writing and preparation. TS designed the experiment, wrote and edited the manuscript. BS and PS contributed to the conception of work, and provided reagents and materials. PW performed MTT assay. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2021年8期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2021年8期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Anti-viral and anti-inflammatory effects of kaempferol and quercetin and COVID-2019: A scoping review

- Valencene-rich fraction from Vetiveria zizanioides exerts immunostimulatory effects in vitro and in mice

- Bitter gourd extract improves glucose homeostasis and lipid profile via enhancing insulin signaling in the liver and skeletal muscles of diabetic rats

- Antioxidant and antigenotoxic properties of Alpinia galanga, Curcuma amada, and Curcuma caesia