The Representation of Semiotic Structures in Language

Steven Bonta

Abstract Based on previous published work on (Mandarin) Chinese, and following a discussion of the properties of the Peircean ontological Categories Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness(as well as their “degenerate” or derivative versions) and their applicability to sign systems, in general, I examine evidence for paradigmatic and syntagmatic structuring,conditioned by these Categories, in Mandarin Chinese, Sora, Tamil, and Sanskrit,languages chosen because of the typological divergence amongst them, and because of the author’s familiarity with them and with their respective cultural milieus. The paradigmatic and syntagmatic structures identified arise in the presence of what I term positive and negative conditioning constraints arising from the Categories themselves, and which are shown to operate at three different levels in language, the morphosyntactic, the lexical,and the phonological. Because of this, a methodology grounded in Peircean semiotic structures is shown to have the explanatory potential to allow for a unified model of language structure, in general.

Keywords: Peirce, Peircean Categories, Peircean Sign, Peircean semiotics, semiotic structures, semiotic grammar, linguistic semiotics

1. Theoretical Underpinnings

1.1 The Peircean Categories

The basis of all cognition, i.e., of all intelligibility, must be some set of ultimate axioms, which approximate as nearly as possible the entelechy of Aristotle (“the Universe qua fact”; Peirce, 1998, p. 304). The most fruitful such schema ever devised is the triad of primordial Categories elaborated by Peirce as the ontological scaffolding of what he styled the “phaneron”, that is, the continuum of cognizable reality. In a coming day, we hope, the Peircean architectonic will become an epistemological commonplace, like the Cartesian assumptions that have dominated most realms of academic discourse for the past several centuries. But for now, at least,Peirce’s most important insights remain somewhat at the periphery of most scientific and metaphysical avenues of inquiry, making the overview in this section a necessary service to the impartial reader.

Decades before Husserl and his phenomenology, Peirce had already concluded that the proper foundation for any architectonic or all-encompassing metaphysic was an examination of the most fundamental and general possible classes of being. While Peirce was far from the first metaphysician to attempt such an ambitious classification of ontological Ultimates, his system distinguishes itself for its breadth and simplicity.Peirce came to believe fairly early in his intellectual development that there were but three ultimate Categories of Being, and he termed them, prosaically enough, Firstness,Secondness, and Thirdness (see, e.g., “On a New List of Categories”, in Peirce, 1992,pp. 1-10, and “The Categories Defended”, in Peirce, 1998, pp. 160-178).

Put as concisely and generally as possible, a First or Firstness ([1]) is “the Idea of that which is such as it is regardless of anything else” (CP 5: 66). A Second[ness] ([2])is “the Idea of that which is such as it is as being Second to some First, regardless of anything else, and in particular regardless of any Law, although it may conform to a law” (ibid.). A Third(ness) ([3]) is “the Idea of that which is such as it is as being a Third, or Medium, between a Second and its First” (ibid.). These three notions being absolutely and self-evidently primordial, it follows that all other phenomena—which we shall hereafter term “composite” or “non-primordial”—are subsumed by them,such that Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness are often characterized in terms of some of their most familiar manifestations. For instance, Peirce was fond of likening Firstness to a “Quality of Feeling”, and pointing out that this Category encompassed,or was the dominant characteristic of, such non-primordial notions as spontaneity,freedom, variety, and freshness.

Following analogous lines of reasoning for the other two Categories, Peirce ascertained that Secondness embraces phenomena like reaction, resistance, otherness(Levinas’ “alterity”), compulsiveness, and corporeality, while Thirdness includes mediation, habit, law, representation, plurality, evolution, continuity, and regularity among its many manifestations.

This taxonomy also gives rise to three “degenerate” Categories, a degenerate Secondness termed Firstness of Secondness, and two species of degenerate Thirdness,Secondness of Thirdness and Firstness of Thirdness. Each of these three degenerate Categories also embraces a range of phenomena, to be detailed hereafter.

It is Thirdness that confers upon reality its evolutionary character, as well as imparting its living, even volitive, substance. As a consequence, the full Categorial1accounting of reality is not of a mere congeries of Objects in blind reaction one with another, but of an infinite continuum of dynamic, purposive Events. And the essence of every Event is the Symbol, or, in the broadest sense, the Representamen, which we will here define as anything whose essential mode of being is representation,sensu lato(i.e., standing in a relationship between a First and a Second). We set aside here an obvious question that Peirce himself wavered on—namely: are all Representamens also Symbols?—except to observe that, in his later writings, he tended towards the affirmative, as his ringing declaration in one of his greatest papers attests.2At very minimum, Symbols are the best-understood of all Representamens. A natural provingground for Peirce’s system, therefore, is that grandest of all known symbolic systems,human language.

Much of Peirce’s output on the Categories was with reference to Signs, which he classified in alignment with the Categories themselves. Peirce’s most famous Sign taxonomy, the triad Icon—Index—Symbol, was grounded in the manner in which a Sign represents its Object. In the case of an Icon, a Sign represents its Object via some kind of qualitative similarity (a photograph, e.g.), i.e., via Firstness; an Index represents its Object by means of physical contiguity or some kind of deixis (a pointing finger, e.g.), i.e., a Secondness; and a Symbol represents its Object via some kind of habit, convention, or law, i.e., by virtue its being a Sign and nothing else (most words, e.g.)—a true Thirdness. Nor was this the only Sign taxonomy that Peirce produced. He also perceived that Signs could be classified according to their inherent nature, as Qualisigns (qualities or Firstnesses acting as Signs), Sinsigns (existents or Secondnesses as Signs), or Legisigns (laws or habits, i.e., Thirdnesses, as Signs). And Signs can be classified according to the way in which the cognizing Mind interprets the Sign’s relationship to its Object; if that relationship is interpreted as a First, then the Sign is a Rheme; if a Second, then the Sign is a Dicisign or Dicent Sign; and if a Third, then the Sign is an Argument.

Not only that, the Sign itself, or, we may say, the semiotic Event corresponding to the Sign in its full sense, is also triadic, consisting of not only the Sign per se, but also its Object and its Interpretant, the last being a further Sign produced as an interpretive response to the Sign, usually a thought.

From Peirce’s well-developed study of Signs, we can discern that the Categories were the ontological basis not only for their classification, but also for understanding their modes of operation. Because of the pervasive nature of Thirdness, for instance,the Sign can never be thought of, in any non-abstractive sense, as a discrete, selfcontained object, but instead must be reckoned as an Event concatenated with an infinite succession of Events, cognizable but never dissociable from the infinite manifold of Sign-Events that constitute reality-qua-semiosis. This state of affairs suggests that triadic reasoning will yield a cognizable but non-atomistic description of any domain of reality.

Our aims in this paper are, firstly, to contribute to the further development of a methodical system of inquiry growing out of the Categories, and secondly, to apply it to aspects of human language, with a view to showing the explanatory power of semiotic structures. Indeed, a thoroughgoing methodology grounded in triadic reasoning is in order if Peircean realism is ever to meet the standards of modern scientific inquiry. The Categories themselves require a universe that is ordered, lawdriven, and cognizable; yet the development of such a methodology was hampered by the fact that Peirce himself was (by his own admission; see “New Elements”, Peirce,1998, p. 309) not well grounded in linguistics, and died before the 20th-century revolutions in science and mathematics were truly underway. We suspect that, had Peirce lived to see the path-breaking linguistics of Sapir, Jakobson, Kurylowicz, and others; had been able to acquaint himself with mathematical innovations like tensors and manifolds; or had lived long enough to learn of the wonders of the quantum and relativistic realms of the physical universe, he would not only have imbibed deeply of these heady draughts, he would have greatly enlarged and refined his architectonic to accommodate such advances. Instead, it is left to those of us swimming in his vast wake to try to assemble piecemeal what he could have accomplished unaided. We note also that, pace Deely’s reservations about a methodological approach to semiotics(Deely, 1990, pp. 11-13) should not be a deterrent, if our aim is to establish semiotics as a truly scientific enterprise.

Because triadic reality is constrained by Thirdness, it will always exhibit an element of regularity, i.e., it will be nomothetic, notwithstanding that this regularity([3]) will always involve elements both of randomness (Firstness/[1]) as well as determinism (Secondness/[2]). The regularity being the basis for Thirdness and hence,for any interpretive Symbol (see, e.g., “Sundry Logical Conceptions”, Peirce, 1998, p.369) implies that triadic reality may be represented as a systematic manifestation—yet the randomness begotten by Firstness also forces us to acknowledge that every triadic system will exhibit its irregularities. This, at least, is well-understood by linguists;Sapir’s famous dictum that “all grammars leak” becomes a guiding principle for all systemic representations of triadic semiotic reality.

1.2 Axioms

Before passing to the task of representing semiotic structures in languages, we must examine the Categories in some further depth, to infer from them as many axioms as we can concerning the characteristics of triadic reality. Since Firstness, Secondness,and Thirdness by definition encompass all phenomena, we can assemble from their essential properties a model of the metastructure of reality, or any subdivision thereof,with the aim of informing the development of our aforementioned methodology. First of all, reality must be triadic, as Peirce so often insisted; this has been so thoroughly and persuasively demonstrated by Peirce that no further elaboration is required. A corollary to the necessity of the Triad is, that reality must be composite, in some sense yet to be made precise.

Secondly, all reality must be hierarchical, or in other words, the general notion of priority (or, in Peirce’s terminology, “gradation”; see Peirce, “On a New List of Categories”, Peirce, 1998, p. 1) must obtain wherever Peircean “phaneroscopy” may cast its beam of inquiry. That this must be so can be readily appreciated, not only from the immanent priority of the primordial Categorial triad itself, vis-à-vis all other possible categories of composite phenomena, but also from the relationships of the Categories among themselves, namely, the fact that the Categories themselves are unequal, as implied by their enumerative designations. A First/[1] is, in some sense, prior to a Second/[2], whether in the sensual or in the conceptual realm, and a Third/[3] is subsequent to both [1] and [2]. At the same time, inasmuch as [2] always involves [1], but not the reverse, and [3] always involves both [1] and [2], but not the reverse, [2] is superior,sensu lato, to [1], and [3] to both [2] and [1].

Thirdly, all existent and nomothetic reality (i.e., reality of which [2] and [3] is constitutive, respectively) is inherently non-commutative. This follows from the preceding axiom, and also from the facts that a) every [2] must involve a [1], but not the reverse, and b) every [3] must involve [2] and [1], but not the reverse. That is:

Here we have taken slight liberties with mathematical notation, for want of better alternatives; it will be appreciated that, e.g., {[2]} is to be understood to mean “the set of all phenomena constitutive of [2]/Secondness”.

The foregoing discussion makes use of Peirce’s term “involve”, which carries a connotation of interiority, alsosensu lato.; that is, to say [2] “involves” a [1] is as much as to say that there can be no alterity without identity, no Index without Icon,no Other without Self, etc., and that, in each instance, [1] is, in one way or another,constitutive of [2]. Similar arguments can be made for [3] with respect to both [1]and [2]. We shall say that [1]inheresin, oris inherent in, [2], and that both [1] and[2]inhere in, orare inherent in, [3], but not the reverse. As for each Category taken absolutely in and of itself, representing,in abstractoat least, its own Universe of Being, we may refer to itsimmanenceorimmanentcharacteristics.

But now arises a question that needs clarification: is there any non-constitutive implicational sense by which [1] requires [2], or [2] requires [3]? To answer this, we must try to think, first, of the characteristics of reality borne out by the Categories.From [1], we infer that reality is stochastic, or, that there is an element of chance in reality. This ontological posture Peirce termed tychism, and the doctrine of tychism also begets such abovementioned qualities as variety and freshness. From [2], we infer that reality is deictic, requiring at minimum a dyad. This notion encompasses such fundamental phenomena as duality, determinism, discreteness, and compulsiveness.From [3], we infer that reality is representational, meaning that it serves to relate a [2]with a [1]. Representation/[3] gives rise, in turn, to the notions of plurality, thought,infinity, continuity, habit, and law.

We now consider the nature of [1], taken by itself. Given that both [2] and[3], which are constitutive of all real phenomena, both require [1] as an inherent,it follows that the only conceivable context for [1] dissociated with [2] and [3] is abstractive—but every abstraction requires an act of cognition, which is perforce a [3];and so every [1] must also require [2] and [3], but not in a constitutive sense. Instead,this requirement is both relational (a Third) and exterior (a Second). To characterize this relationship, we say that [3]adheres to, oris adherent to, [1], and we denote it as follows:

Because all acts of deliberative abstractive cognition also require an Index (a Second),we may also assert that

and

Only in this way can we understand how it is that, e.g., a First can have representational force, as an Icon, Qualisign, or Rheme; the representational element, in such instances, is adherent to the sign.

This line of reasoning gives rise to another fundamental property of reality,namely, that representational phenomena may be immanent, adherent, or inherent and that, inasmuch as the abstractive act described previously may apply to any of the Categories, the triad immanence/inherence/adherence may apply to any element of reality. As a consequence, any sign may be regarded either as an independent thing in and of itself/[1], as standing in relation to someens exterior/[2], or as a composite of inherents/[3]. From this we conclude that all reality is implicational, whether via immanence, adherence, or inherence.

From the composite, hierarchical, and non-commutative characteristics of reality we infer the universality of thesyntagm, that is, the ordered sequencing of all constituents of the dynamic reality constitutive of all events. In linguistic semiosis,the syntagm is manifest as morphosyntax. All syntagms are representational.

Finally, we may infer from all of the foregoing that all reality is classificatory.This follows from the originary character of triadic realityquaclassification, and is given additional vigor by such notions as plurality and law (Thirds). Any classification being itself a sign, it follows that it may be predicated either upon immanence,adherence or inherence, or any proportion of these in combination with the others.In practice, of course, human classification, via language, art, or culture in general,always involves some degree of adherence, or, as we have elsewhere styled it, lensing,whereby a particular Category-sign is given representational primacy (Bonta 2018).In such instances, then, [1] may be selected to represent [2], [23], [3], etc. More concretely, we might find, for example, that whereas “music,” taken with respect to other members of the set of “things constitutive of a culture-sign” (which set might also include science, mathematics, engineering, religion, philosophy, clothing,architecture, language, etc.), would be regarded inherently as a First (where, e.g.,sculpture might be a Second and mathematics a Third), yet music might represent, by adherence, a Second or a Third, in addition to, or rather than, a First. After all, music may be evocative of a pure quality of feeling ([1]), but it may also be evocative of sensual or compulsive action ([2]), or even abstractive cognition ([3]).

From the classificatory character of triadic reality we are led ineluctably to the notion of theparadigm, the orderingin potentiaof all elements of a related class,among which obtain relationships of both similarity and priority.

Leaving aside the question of the primordiality and universality of representation,we assume, based on the foregoing arguments, that semiosis—like all other phenomena grounded in the Categories—represents itself structurally (both syntagmatically and paradigmatically), and that the task of classifying and evaluating semiotic structures is best undertaken with the Categories themselves as the basis thereof. Any methodology of classification perforce involves a system, and, in this case, any such system should be an Index involving an Icon, writ large, suggestive of the manner in which the Categories themselves have been shown to operate.

The principle of priority described previously is made explicit in the linguistic notion of a mark, or markedness; for, just as a primordial hierarchy is implied by the relationship of priority among the constituents of the primordial Triad, so too we expect to find groups of semiotic objects of inquiry that may be differentiated hierarchically, based on the presence or absence of a mark or marks, whose presence we shall denote by “+”. Since we are using the Categories themselves as our basis, we assume that they themselves may constitute the marks referred to, as, e.g., [+1], [+12],etc., or in other words, that any conceivable mark, whatever its explicit contours,may—like all non-primordial phenomena—be represented in terms of the Categories.That this is admissible is easily demonstrated. Assume we have a mark of any type,except that it cannot be a Category, pure or degenerate, per se, and let us denote it[+μ]. Assume further two Objects, X and Y, brought into a classificatory relationship or set, and that one of them, X, does not involve [+μ], while the other, Y does. This relationship we may denote as {X, Y[+μ]}. It will be appreciated that, no matter the immanent character of [+μ], within this classificatory set it operates as some Quality,i.e., a Firstness, of Y with respect to X. That is, [1] is immanent in [+μ], and as such,it may be represented as [+1]. But as we have already seen, every act of classification involves representation, which for our purposes requires some act of cognition. This being the case, both [3] and [2] are adherent to [+μ], and could therefore be likewise represented as its embodiment, every act of cognition being of the nature of a Symbol,and the intrinsic nature of a Symbol being pure representation without reference to any iconic or indexical constraint. Put simply, anything of the nature of a Symbol represents purely by being so regarded, and for no other reason (“New Elements”,Peirce, 1998, p, 321).

Now a mark having the nature of a Symbol, albeit a rudimentary one, it follows that it will also involve an Index, which, by being deictic, will have the effect of limiting or establishing boundary conditions for the class of Objects thereby denoted,with respect to some other, more general Symbol. Consider the Word-Symbol“mammal”, denoting a certain type of creature within the larger class denoted by‘animal.’ That ‘mammal’ is marked with respect to “animal” may be seen by the Index embracing the set of characteristics that differentiate mammals from all other members of the animal kingdom. This composite Index serves to call attention to those differentiating characteristics (which, in the manner of all triadic semiosis, are neither absolute nor exceptionless, as with the case of outliers like the bat and the platypus).

But as we have seen, the Categories themselves, including degenerate forms, may serve as marks. This means that any of them may be enlisted, by adherence, to serve as an Index determining the boundary conditions for some class of non-primordial phenomena qua Objects. In other words, an act of cognition (a Third) may assign, e.g.,[+12] (i.e., the degenerate Category Firstness of Secondness) as a mark (a Second denoting a First) to some congeries of Objects, thus transforming them into a class, i.e.,a single composite Sign. But because Thirds embrace both the notions of habit and generality, it follows that any such Third may spread from one Mind-Symbol to the next (creating a community of Mind-Symbols wherein this particular Symbol-as-Mark becomes established habit), and may be diffused outward from its original domain of application to approach the entire continuum of cognizable Being (see “The Law of Mind”, Peirce, 1992, pp. 312-333, for Peirce’s famous description of this process).In this way do Culture-Signs come into being; the process by which one or more Category-Symbols comes to serve as a maximally general signifying Index by which all reality is represented is called lensing, as already mentioned. In the foregoing example, we say that the lens is [12].

Writ large, lensing is the way in which a Mind-Symbol “reduce[s] the manifold of sensuous impressions to unity”, per Peirce (“On a New List of Categories”, Peirce,1992, p. 1). It is a universal condition imposed upon the mind by what we might style the “tyranny of Secondness”, the all-encompassing constraint operative in a corporeal Universe. It is Secondness, more than the other Categories, that foremost urges itself upon the senses. This tyranny is responsible for the widespread fallacies of materialism and kindred schools of thought that cannot see beyond tangible reality.

This being the case, it follows that our primary objects of inquiry in any semiotic system must beexplicit, or in other words, must be elements with Secondness strongly inherent. The explicit aspects of language include not only the morphosyntactic“surface structure”, but also the lexicon and phonology. These all manifest explicit semiotic structures that have been selected by a given speaker community to represent the “manifold of sensuous impressions”. Morphologizing is a well-studied process by which Word-Symbols (or lexemes) are selected as Indexes signposting morphosyntactic semiotic structures. This line of reasoning gives rise to the notion of themorphosemiotic, that is, that all form is associated, however haphazardly, with meaning, and that syntactic, morphological, lexical, and phonological structures are,at root, semiotic in nature—indeed, “structure” as such is the Indexical manifestation of semiosis. Put otherwise, the assumption of the morphosemiotic implies that explicit morphology confers semiotic prominence, i.e., signifies semiotic priority.

Our hypothesis is that study of these morphosemiotic structures in any language will reveal the Categorial lens associated with that language, and that, inasmuch as that lens operates after the manner of a Symbol, it will impose structural unity and consistency across the entire composite (but withal interconnected) Language-Sign(i.e., language qua sign).3Further, because every semiotic lens is associated with one or more Categorial marks4, we propose that in any Language-Sign, these Categorial marks act as constraints, in the same manner as other linguistic constraints, but at a maximally general, primordial level. This means that we may have both positive and negative constraints; returning to the foregoing example, [+12] is a positive constraint—but it also presupposes [-3], a negative constraint. These constraints are expected to condition both syntagmatic and paradigmatic structures. In the following case studies, we will see more concretely how both positive and negative Categorial constraints are manifest, in both paradigmatic and syntagmatic contexts, at multiple levels of language.

2. Case Studies

2.1 Mandarin Chinese and [12]

The reader will already have appreciated the potential complexities and pitfalls of semiotic analysis along the lines we are proposing. The very nature of triadic reality—evolutionary, continuous, and often stochastic—tends to generate exception-riddled complexity whereof the regularity can be very difficult to discern. Signs, including Category-Signs, often blend and hybridize, making it extremely difficult to tease out the semiotic properties of each constituent Sign from the amalgam. We seek to reduce the complexity of the subject matter while ensuring, as far as possible, that our own observations are accurate. The only way to do this is to seek languages that have proven less susceptible to foreign influence, and to limit our inquiry to languages that we have some familiarity with. Otherwise put, relying on data from unfamiliar languages or from languages with strong borrowed elements (like modern English)is not the best way to establish the theory. Instead, I will rely only on languages and language areas where I have significant personal expertise, from regions that have proven to be relatively opaque to foreign importations. Our approach will be to examine each language at the phonological, lexical, and morphosyntactic levels, and identify the dominant typological characteristics at each level. We will examine those characteristics in light of the Peircean Categories, to see whether a particular Category(pure or degenerate) appears to predominate. As we have already tested this method in previous work with Mandarin Chinese (Bonta, 2020), we summarize the results of that study first, to show how this method may yield fruit. In subsequent sections, we will apply it,mutatis mutandis, to other languages.

In previous work, I found Mandarin Chinese (hereafter “Chinese”) to be subject to [+12], or Firstness of Secondness, as the primary constraint. To see how this has proven to be the case, we first must examine the characteristics of [12], one of Peirce’s three “degenerate” Categories. In the case of [12], as also the other two degenerate Categories [13]/Firstness of Thirdness and [23]/Secondness of Thirdness, Peirce—in the portions of his writings that have so far been published—is comparatively reticent, reserving most of his exemplifications and in-depth descriptions for the“pure” Categories Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness. The result is that, whereas we can rely comfortably on Peirce’s characterizations of the latter three, the former three must, in many respects, be fleshed out by modern investigation. This, it seems,is a major uncompleted task of Peirceana inasmuch as, from the linguistic evidence to be presented herein, the degenerate Categories appear to be at least as prominent in semiotic structuring as the pure Categories, and perhaps more so. For example,based on our results from Chinese, we would anticipate that [12] is a prominent(though perhaps not exclusive) structuring constraint in many of the major languages of southeast Asia, of the Tibetan plateau, and of China itself, since these languages all bear significant typological similarities with Chinese in some or all of the criteria that will be shown following.

Peirce characterized Firstness of Secondness/[12] as follows:

Category the Second has a Degenerate Form, in which there is a Secondness indeed, but a weak or Secondary Secondness that is not in the pair in its own quantity, but belongs to it only in a certain respect. Moreover, this degeneracy need not be absolute but may be only approximative. Thus a genus characterized by Reaction will by the determination of its essential character split into two species, one a species where the Secondness is strong, the other a species where the Secondness is weak, and the strong species will subdivide into two that will be similarly related, without any corresponding subdivision of the species.For example, Psychological Reaction splits into Willing, where Secondness is strong,and Sensation, where it is weak; and Willing again subdivides into Active Willing and Inhibitive Willing, to which last dichotomy nothing in Sensation corresponds. (CP 5: 69)

In another paper, Peirce gave a few more details about the nature of Firstness of Secondness with respect to “pure” Secondness:

[T]here is a degenerate sort [of Secondness] which does not exist as such, but is only so conceived. The medieval logicians (following a hint of Aristotle) distinguished between real relations and relations of reason. A real relation subsists in virtue of a fact which would be totally impossible were either of the related objects destroyed; while a relation of reason subsists in virtue of two facts, one only of which would disappear on the annihilation of either of the relates…. Rumford and Franklin resembled each other by virtue of being both Americans; but either would have been just as much an American if the other had never lived. On the other hand, the fact that Cain killed Abel cannot be stated as a mere aggregate of two facts, one concerning Cain and the other concerning Abel. Resemblances are not the only relations of reason, though they have that character in an eminent degree. Contrasts and comparisons are of the same sort. Resemblance is an identity of characters; and this is the same as to say that the mind gathers the resembling ideas together into one conception. Other relations of reason arise from ideas being connected by the mind in other ways; they consist in the relation between two parts of one complex concept, or, as we may say, in the relation of a complex concept to itself, in respect to two of its parts…. But [all these relations] are alike in this, that they arise from the mind setting one part of a notion into relation to another. All degenerate seconds may be conveniently termed internal, in contrast to external seconds, which are constituted by external fact, and are true actions of one thing upon another. (CP 1: 365)

In my own recent work, I offered the following clarification:

Robertson (1994), in his examination of English verb affixal morphology in light of the Peircean Categories, characterizes Firstness of Secondness as existing “where the mind sees a single notion as two, or where one of the two objects is vague and the other a more focused version of the other”.

In other words, Firstness of Secondness always involves an unequal dichotomy. It is the result of the mind resolving a single idea into two objects, complementary or opposing.We might add that, just as a pure Firstness must be understood to absolutely exclude all Seconds and Thirds (CP 1: 358), a Firstness of Secondness will, by its very nature, tend to exclude Thirdness altogether. (Bonta, 2020)

Our task, then, was to examine the lexicon, the morphosyntax, and the phonology of Chinese, to see whether a) the notion of the “unequal dichotomy” characteristic of[12] is given any prominence and b) whether Thirdness/[3] is in any discernible way minimized. In other words, we looked for lexical, morphosyntactic, and phonological evidence for the constraints [+12] and [-3].

2.1.1 The Chinese lexicon

Consider first the Chinese lexicon as a starting point for looking for conditioning constraints. There are three general conditioning features of Chinese lexical entries,all of them conspicuous and readily noticed by any student of the language. These are: first, the relatively small number of admissible syllables in Chinese (no more than approximately 1300 in all, or 400 if tonal distinctions are ignored—this in comparison to at least 10,000 in English); second, the fact that every syllable has full lexemic value (leading to an enormous number of homophones in Chinese); and third, the fact that the overwhelming majority of actual Chinese words in common usage are dilexemic, that is, they consist of two syllables, each of which is represented by one written sign and which corresponds in its own right to an independent lexeme.

Considering first the paucity of admissible syllables, and the fact that every such syllable represents a full lexeme, we observe that the organization of sounds into syllables and words, in general, tends to beget enormous variety, at least in English.This is because the relationship between sound and meaning is primarily Symbolic,or in other words, premised upon a given sound configuration’s being assigned a meaning and upon nothing else. It is the immanently arbitrary character of Symbols, in general, that tends to impart diversity, both in length and in phonological complexity,to a lexicon. In English, for example, if we take a fairly random sampling of wellknown mammals, we may note significant differences in sound shape, syllable count,and the like: {elephant, tiger, giraffe, rhinoceros, moose, antelope, hippopotamus,lion, bear, wolf}. None of these terms is analyzable in any way (aside from foreign roots, e.g., the Greek roots evident inrhinocerosandhippopotamus), i.e., the ‘gi-’of ‘giraffe’, the ‘ti-’ of ‘tiger,’ the ‘-phant’ of ‘elephant’, etc., have no independent significance; they cannot be separated from the rest of the respective Word-Symbols to which they belong.

But the situation in Chinese is entirely different. The equivalent Chinese set for the above animal words is as follows: {dà xiàng, lǎo hǔ, cháng jǐng lù, xī niú, tuó lù,líng yáng, hé mǎ, shī zi, xióng, láng}. Every one of the syllables in the preceding set is meaningful, with the literal meanings for the multisyllabic entries being as follows:

Leaving aside for a moment the obvious superfluities of some of these words(e.g., Why ‘old tiger’, if the lexemehǔmeans ‘tiger’ by itself?), we see that, in stark contrast to English, Chinese has no undecomposable polysyllabic words. Note also that nearly all of the above monosyllabic lexemes have multiple possible meanings,typically indicated by a range of different written signs. For example, the lexemesyllableshī, ‘lion’ (represented by the sign狮) may also signify ‘err, make mistakes’(失), ‘master, teacher’ (师), ‘poem, poetry’ (诗), ‘carry out, execute’ (施), ‘damp,wet’ (湿), and ‘corpse’ (尸). All of these lexemes are identical as to their sound shape(including the tone; if we allow for the many additional possibilities where tone alone is differentiated, we will arrive at dozens of homophones or near-homophones). Only in writing may these words be differentiated, via the different form of the characters used to represent them. And we would obtain similar results for every single lexemesyllable in the preceding list of animal names, and, indeed, for each of the roughly 1300 allowable syllables in the Chinese syllabic inventory.

The effect of this peculiar lexemosyllabic typology is to reduce, as far as possible,the allowable number of sound configurations participating in word formation.Limiting as far as possible—while still maintaining intelligibility—the number of available syllables, in combination with disallowing any unanalyzable polysyllabic lexemes, reduces as far as possible the arbitrary relationship between sound and meaning. Otherwise put, reduction of words in Chinese to analyzable combinations of a comparatively small set of syllables has diminished as far as possible the arbitrary—and therefore the symbolic—aspect of word formation (without, of course, obliterating it entirely, since linguistic signification without some degree of symbolism is impossible). All Symbols embodying Thirdness/[3], as we have seen previously, we may represent this minimizing of pure Symbolism as the negative constraint [-3]pervasively conditioning the Chinese lexicon.

As for the positive constraint [+12], the defining typological characteristic of the Chinese lexicon, as the reader may have noticed from the aforementioned set of animal names, is its overwhelming preference for disyllabic (and therefore dilexemic) words. This preference embraces not only nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, but also extends even to conjunctions and prepositions. In every word class,monosyllabic/monolexemic entries may also be deployed, but they tend to be far less commonly used than dilexemes, and far less frequent in informal speech than in more literary contexts. This is in part because the preponderance of dilexemes in the Chinese lexicon is very much an active evolutionary process, or, we might say, a very conspicuous operation of the Symbolic Third bringing Chinese into ever-more exact conformity with its conditioning lens.

The phenomenon of alternative monosyllabic and disyllabic words in Chinese is well-known, and is referred to as “elastic word length”. Duanmu (2013) found that 80 to 90 percent of all Chinese words have elastic length, with 92 percent of nouns and 83 percent of verbs in the sample he worked with displaying this characteristic.

Dilexemic words may conform to any of a number of common patterns, including figurative oppositions (e.g.,dōng-xī, ‘thing’, literally, ‘east-west’, orshēn-qiǎn,‘depth’, literally, ‘deep-shallow’), redundant pairings (e.g.,bāng-zhù, ‘help’, literally,‘help-help’ andyán-jiū, ‘research’, literally, ‘research-research’), phrasal verbs that incorporate a direct object (e.g.,zuò-fàn, ‘cook, prepare food’, literally, ‘make-food’),and pairs involving a “light” syllable with no literal meaning that serves to do nothing more than create a word in its “full form” (e.g.,dāo-zi, ‘knife’, whereof the second element,-zi, simply means ‘offspring’ in its original, literal form, and is now used to create hundreds of full-form Chinese words out of original lexemes—in this case,dāo,‘knife’—which were the historical words in and of themselves, and which still may be found as monosyllabic lexemes in very formal or literary contexts). Other examples of“light” syllables include-shì, ‘be, is, are’,lǎo-, ‘old; venerable’, anddà-, ‘big’. A few examples of disyllabic words using these light syllables are shown on Table 1:

Table 1. Disyllabic words with “light” syllables -zi, -shì, lǎo-, and dà-

hóu-zi, ‘monkey’ (hóu, ‘monkey’)shì-zi, ‘persimmon’ (shì, ‘persimmon’)yàn-zi, ‘swallow’ (yàn, ‘swallow’)zhú-zi, ‘bamboo’ (zhú, ‘bamboo’)dà-xiàng, ‘elephant’ (xiàng, ‘elephant’)dà-gŏu, [colloquial] ‘dog’ (gŏu, ‘dog’)dà-nǎo, ‘brain’ (nǎo, ‘brain’)dàn-shi, ‘but’ (dàn, ‘but’)hái-shi, ‘still’ (hái, ‘still’)?

Some examples of disyllabic words involving redundant pairings of lexemes are shown, along with both translations and literal glosses, on Table 2:

Table 2. Disyllabic words with redundant pairs of lexemes

This love of dilexemic, disyllabic words in Chinese has arisen as a result of a compulsive need to create complementary pairings at the lexical level as often as possible. But whence arises this need in the first instance? In previous work (Bonta,2020), we argued that this conspicuous and pervasive typological characteristic of the Chinese lexicon is a consequence of the positive conditioning constraint [+12],that is, the lens of Firstness of Secondness. Recall that Firstness of Secondness is characterized by “an unequal dichotomy… the result of the mind resolving a single idea into two objects, complementary or opposing”. The dichotomous character of the overwhelming majority of Chinese lexical entries can scarcely be questioned on the evidence; but in what sense may the opposing or complementary entries of a given dilexemic Chinese word be interpreted as unequal? In the first place, owing to the immanent nature of the Categories already set forth (see Peirce, “On a New List of Categories”, Section 2), we would expect, foranytaxonomy arising directly from a Categorial lens, a self-evident hierarchy or gradation. The “unequal dichotomy” is simply this hierarchical character manifest in [12]. In the case of dilexemic Chinese words, we can easily observe abundant evidence for the “unequal dichotomy” as a manifestation of [+12]. For example, a large number of dilexemic Chinese words drop the tone on the second entry, suggesting iconically a privileging of the first over the second syllable/lexeme. Some examples include pairs in-shì, likedàn-shiandháishinoted previously, in which the tone of -shì is neutralized, as well as many other such pairings (in general, the more common the word, the more likely such tonal neutralization will take place).

Perhaps even more tellingly, Chinese frequently forms new disyllabic compounds out of existing disyllabic words, by dropping one of the two syllables in each entry.The resulting compound then furnishes strong lexical evidence that the syllable/lexeme from each original word chosen to participate in the resulting compound is, in fact, the semantically “dominant” or prior entry of the original word. And this notion is given additional credence by the fact that, in cases where the same word forms a multitude of different compounds, it is usually the same syllable that is chosen to represent the original disyllabic word in each of the resultant compounds. Table 3 furnishes several examples to illustrate how this process works:

Table 3. Chinese compounds formed from reduced pairs of dilexemic words

It should now be evident from the evidence given that the Chinese lexicon is pervasively and consistently conditioned both by the positive constraint [+12] and the negative constraint [-3]. Space will not allow a fuller exploration of the lexical evidence for these two constraints, but much more evidence might be adduced in a fuller treatment of this phenomenon in future research.5

2.1.2 Chinese morphosyntax

The fundamental purpose of language being the construction of communicative propositions, it follows that the most essential characteristic of any language is the way by which it unifies the two fundamental parts of any proposition, the Subject and the Predicate. Regarding the semiotic sense of these two terms familiar to every grammarian, Peirce pointed out that the Subject, writ large, consists of the set of Indices proper to a given predicate, which in turn encompasses the entirety of ideas involved in the verb or other grammatical predicate:

[I]n order properly to exhibit the relation between premises and conclusion … it is necessary to recognize that in most cases thesubject indexis compound, and consists of asetof indices. Thus, in the proposition “A sells B to C for the price D”, A, B, C, D form a set of four indices. The symbol “____ sells ____ to ____ for the price ____” refers to a mental icon, or idea, of the act of sale, and declares that this image represents the set A, B,C, D, considered as attached to that icon, A as seller, C as buyer, B as object sold, and D as price. If we call A, B, C, D foursubjectsof the proposition and “____ sells ____ to ____for the price ____” as predicate, we represent the logical relation well enough, but we abandon the Aryan syntax. (“Of Reasoning in General”, Peirce, 1998, pp. 20-21)

This being the case, there are, broadly speaking, three morphosyntactic strategies deployed by languages to effect the colligation of Subject and Predicate, as we have noted previously (see Bonta, 2018): agreement, contiguity, and blending. Any of these three strategies may represent the Symbol of assertion, whereby the mind brings into relationship Subject and Predicate, by affirming, in effect, that the set of Indices corresponding to the semiotic Subject are, indeed, related to the Icon or mental image associated with the Predicate. The Symbol of assertion is above all a mental act, or Symbol of consciousness; it is often, although not always, signalized overtly by a copula or by some sort of verb inflection. Note that the foregoing is a semiotic typology, not a strictly formal grammatical one, and as such will not always neatly accommodate the various morphosyntactic typologies, like isolating and agglutinative,favored by linguists.

Blending refers to the formal conflation of morphemes representing Subject and Predicate into a single lexeme, and is especially conspicuous in so-called polysynthesis (the creation of extremely long and complex “sentence words”, widely attested in Native American and Australian Aboriginal languages, among others),but is also present to some degree in agglutinative and fusional languages. Blending,as we have elsewhere shown (Bonta, 2018), is meaning association qua Firstness,because it seeks to merge the pair Subject and Predicate into an undifferentiated singularity ([+1]), and also because it minimizes lexical boundaries, contrasts, and distinctions ([-2]).

Contiguity refers to the strategy of juxtaposing Subject and Predicate temporospatially, such that the mind is directed to associate the two; this process is tantamount to meaning association via Secondness, because it relies critically on deixis for its effect. In so-called analytic or isolating languages, this strategy is especially conspicuous.

Agreement, as we have elsewhere noted, “involves the purely symbolic relationship between word pairs, like subject-verb and modifier-modified, signalized by affixation. Thus, for example, there is no formal similarity between the Spanish verb affix-mos, which marks the first person plural, andnosotros/nosotras, the pronoun to which it refers, or between-s, which marks the second person informal singular, andtú, the second person informal singular pronoun, but the agreement relationship serves to connect these two elements notwithstanding” (Bonta, 2018). In other words, agreement is a strategy for meaning association qua Thirdness, because it relies purely on conventional, symbolic relationships—relationships which, in languages with rich inflectional systems of agreement like Sanskrit, may be mediated across considerable morphosyntactic distances, minimizing reliance upon word order.

If the negative constraint [-3] conditions Chinese morphosyntax as we have shown it to do for the lexicon, we would certainly expect a minimization of agreement([3]) as a strategy for meaning association, and this is indeed the case. Mandarin Chinese is as close an approximation to a pure analytic language as any attested.There is absolutely no subject-verb (or, for that matter, object-verb) agreement in Chinese. Moreover, there is little overt inflectional evidence of a copula or verb inflection; Chinese verbs exhibit not only no person or number, but also no inflectional tense or mood. The verbshì, ‘be, is, am, are, was, were’, is used only with subject complements. There are no irregular or suppletive verb forms. Typologically,the morphosyntax of Chinese is in diametric contrast to the richly-inflected Indo-European languages (including even the comparative simplicity of modern English;Chinese learners of English are greatly vexed by the need for the third-person singular present tense-sand the past-tense-ed, for example).

We note also the near-total absence of an overt plural marker in Chinese, a typological oddity. The suffix-mendistinguishes plural pronouns from their singular counterparts (e.g.,wŏ-men, ‘we’ vs.wŏ, ‘I’), and may also be optionally deployed after nouns denoting persons (especially family members and children), but otherwise,no morphological distinction is made in Chinese between singular and plural. In other words, “plurality” is a notion accorded no morphosemiotic prominence—but this is not surprising in light of our contention that [-3] is a negative conditioning factor. Plurality, after all, is one of the most conspicuous phenomena associated with Thirdness. Thus, we take the lack of an overt plural marker for the overwhelming majority of Chinese nouns to be another consequence of the negative constraint [-3].

As for the positive constraint [+12], we consider the manner in which the(Peircean semiotic) Subject is morphosyntactically associated with the Predicate in Chinese, wherever the Subject consists of multiple arguments. Whenever the semiotic Subject consists of only a morphosyntactic subject (i.e., the verb is intransitive, and the subject is its only argument), the Subject-Predicate relationship is expressed via contiguity/[2], as inwŏ kànjiàn, ‘I see’, where subject/Subjectwŏprecedes the verb/Predicate. Otherwise couched in linguistic terminology, subject incorporation is not admissible in Chinese.

However, whenever the semiotic Subject consists of a morphosyntactic subject and direct object (i.e., the verb is transitive, and the subject and direct object are its only two arguments; Peirce termed Subjects with two arguments dyads), the direct object is in some cases incorporated into the verb in a verb-object compound, and in others either precedes the verb (sometimes, though not always, accompanied by the preposing particlebǎ) or follows the verb, as a discrete entry. In the first case (i.e.,of direct object incorporation), the relationship verb-direct object (or, in other words,the relationship between the Predicate and the part of the Subject corresponding to the patient or grammatical direct object) is accomplished via blending/[1], and in the second case (i.e., of discrete direct objects), it is accomplished via contiguity/[2]. In either case, the grammatical subject (i.e., the part of the Subject corresponding to the agent or grammatical subject) is kept discrete, as with intransitive verbs described previously. Thus, in instances where the direct object is incorporated into the verb, the Subject-Predicate relationship is manifest as a structural dichotomy, with the subjectverb part represented via contiguity/[2], and the subject-direct object part represented via blending/[1]. Examples of each of these cases follow:

In cases where the semiotic Subject consists of either 1) a subject and a second argument that is not a direct object or 2) more than two grammatical arguments (as,e.g., a subject, a direct object argument, and a locative argument), one (but not more than one) of the additional arguments besides the subject or direct object may be represented via a postverb, a sort of preposition-like verb (or verb-like preposition)that is affixed to the main verb, creating a species of compound verb that in effect incorporates the place or manner of the action into the grammatical predicate. Such a postverb iszài, meaning ‘[be] on, in’, and frequently incorporated as a postfix into verbs likefàng, ‘put, place’ (fàngzai, ‘put on, place on) andtú, ‘smear’ (túzai,‘smear on’). In some cases, postverb compounds may arise in circumstances where there is no direct object, but an additional argument, such as a locative, is called for.For example, the aforementioned-zàimay be affixed tozhù-, ‘live’, to formzhùzài,‘live in’. Another such postverb that requires a locative argument and often occurs in intransitive contexts is-dào, ‘[go] to, towards’, as inbāndào, ‘move to’.

Such postverbs and the compounds created therewith are a central characteristic of Chinese morphosyntax, and are introduced early in Chinese pedagogy. Some examples of the uses of such postverbs follow:

Recall that, as previously noted, the Peircean semiotic Subject consists of the entire set of logical arguments associated with the predicate; thus, the “Subject” of‘John gives a book to Mary’ is the set {John, Mary, book}. In similar fashion, the Subject of the Chinese verbfàngin the second example under Case 5 preceding is the set {tā, shū, bēibāo}, since the notion of “putting” always involves a “putter”, a“thing which is put”, and a “location where it is put”. All of these three arguments are intrinsic to the meaning of put/fàng. It will be appreciated from the preceding examples that, in cases where the semiotic Subject may be resolved into three or more grammatical arguments, one argument other than the subject/agent and direct object/patient may be represented as partially incorporated into the Predicate by the blending of a locational or directional postverb with the main verb as a single compound. Moreover, for intransitive verbs with a locational or directional argument,a postverb compound construction is typically deployed along with a discrete subject.Along with instances of discrete subjects paired with incorporated direct objects noted under Case 1 preceding, Cases 4 and 5 all involve representation of the semiotic Subject as a morphosyntactically iconic dichotomy whereof either a) the grammatical subject is a discrete entry and the direct object is a blended (incorporated) entry (Case 1), b) the grammatical subject is a discrete entry and the locational or directional argument a partially-blended entry as a postverb (Case 4) or c) the grammatical subject, direct object, and, potentially, other arguments (like the indirect object) may all be represented as discrete entries vis-à-vis the verb, while one additional argument(locational or directional) is represented as a partially-blended entry with the verb(Case 5). For the set of discrete arguments, the mode of representation, again, is contiguity/[2], and for the blended direct object or partially-blended locational or directional argument, blending/[1].

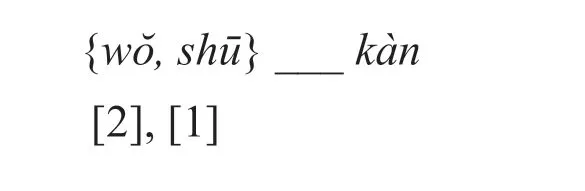

For greater clarity, we may represent the composite structure of the Chinese Subject with respect to the predicate as follows:

Here, {Sn} is the set of n terms corresponding to the semiotic Subject (for example,the subject and direct object), [Cn] is the Categorial constraint corresponding to the mode of relationship with the Predicate of each of the n terms of the semiotic Subject, ___ represents the Subject in relation to the Predicate (the choice of notation motivated by Peirce’s characterization of the potential Subject as “blanks to be filled”[“New Elements”, Peirce 1998, pp. 310-311]), and P is the predicate. For example,Case 1 foregoing may be represented as follows:

This diagram shows that the set of terms representing the Subject ({wŏ, shū})are represented as connected to the predicate (kàn) via a Secondness/[2] and a Firstness/[1], respectively. In cases such as this, the Subject is represented morphosyntactically as a simple dichotomy [1], [2].6

On the other hand, Case 4a is represented as follows:

The motivation for this representation is that, whereas the grammatical subjecttāmenstands in a relationship of contiguity with the predicatezhù, the second argument, the locationběijīng, stands in a morphosyntactic relationship consisting of both a discrete element (the nounběijīng) and a blended element (the indicator of spatial relationship-zài). In other words, on careful examination we observe that the Subject is resolved,in this case, not into a simple [1], [2] dichotomy but into a [12], [2] dichotomy, the choice of [12] for the locational term being motivated by its obvious additional resolution into a stronger ([2]) and weaker ([1]) morphosyntactic element.

For Case 5a, we have a more complex instance of a Subject composed of three separate elements, to wit:

In this instance, we see that the grammatical subject and direct object are represented as discrete elements with respect to the predicate ([2]), while the destinational argumentjiàoshìis represented as a composite of the blended directional marker-dàoand the discrete elementjiàoshì([12]). Note that, in this, as with other examples,the locational markers and prepositional particles do not figure in any significant way into the semiotic structures under consideration, at this level of analysis, though it is likely the case that they will also require mapping at subtler levels of semiotic representation. For now, our primary concern is the relationship between Subject and Predicate, for which explicit particles, postfixes, and the like, serve merely to make explicit semiotic information already inherent in the Predicate. Note also that the rule stated previously that, in the case of more than two arguments (beyond a subject and direct object; Peirce termed Subjects with more than two arguments polyads),one—but not more than one—additional argument may be represented as a partiallyblended element via a postverb construction—amounts to a rule that, if there are multiple arguments represented via the same Categorial constraint, that constraint will be [2], not [1] or [12]. For Case 5a shown above, this results in a double dichotomy by bifurcation, or in other words, the Subject is first resolved into a strong element(the subject and direct object, both [2]) and a weak element (the destinational argument, [12]), and the strong element of the Subject (the subject + direct object)is further resolved into a finer dichotomy, also consisting of a strong (subject) and weak (direct object) component. Recall that the admissibility of such bifurcations in[12] is described by Peirce as follows: “[A] genus characterized by Reaction will by the determination of its essential character split into two species, one a species where the Secondness is strong, the other a species where the Secondness is weak, and the strong species will subdivide into two that will be similarly related, without any corresponding subdivision of the species.” (CP 5: 69)

Thusly is the dichotomy of [+12] clearly manifest in Chinese morphosyntax insofar as the Subject and its relationship with the Predicate are concerned. That it is an unequal dichotomy consistent with the character of [12] previously established is also plain: [2]/contiguity is clearly the default strategy, as evidenced by the fact that the grammatical subject/agent is never incorporated into the verb, and, as noted previously, it is the only strategy that may be deployed with multiple elements within the same Subject. The direct object/patient may be incorporated, but if there are other arguments present beyond subject/agent and direct object/patient, only certain of those, and not the agent and patient, are susceptible to incorporation, and never more than one of them in a given proposition.

In addition to the Subject and its relationship with the Predicate, the Chinese predicate per se may be split into contrastive or complementary elements via a range of strategies, all of which have the effect of representing the Predicate as an unequal dichotomy emblematic of [12]. One of these strategies, familiar to every introductorylevel Chinese student, is the contrastively-structured yes-no question, in which the verb is repeated, and the second instance is negated with one of two negative prefixes,bú-orměi-, as inshì-bú-shì, ‘Right?/Isn’t that so?’ (literally, ‘be-no-be’), oryŏu-měiyŏu, ‘Is/are there?/Do you, they/Does he, she have?’ (literally, ‘There is-no-there is’).For example:

nǐ xǐhuan shàng hǎi, shì-bú-shì?

you like Shanghai be-not-be

‘You like Shanghai, right?’

tā yŏu-méi-yŏu

he have-not-have

‘Does he have [it/them/any, etc.]?’

tāmen yào-bú-yào qián

they want-not-want money

‘Do they want money?’

Per Peirce, the affirmative and the negative are embodiments of Firstness and Secondness, respectively (CP 1: 359), and so the affirmative and negative in such dichotomies correspond to the weak and the strong elements of [12].7We may represent such split predicates schematically according to the following formula:

where (Pi/j) signifies the resolution of the Predicate into two contrastive elementsiandj, and the superscript [Cij] represents the Categorial correspondence ([1] or [2])for each element. In combination with our previous representation of Subjects, we represent a complete Subject-Predicate for such split predicates as:

We represent the above example

tāmen yào-bú-yào qián

as follows:

This pattern of predicate-splitting is also used for experiential yes/no interrogatives; one common strategy is to useméiyou, ‘not-have’. For example:

nǐ qù-guo zhōngguó méiyou

you go-EXPERIENTIAL China not-have

‘Have you been to China?’

or

nǐ yóu méiyou qù-guo zhōngguó

you have not-have go-EXPERIENTIAL China

We represent this sentence diagrammatically as follows:

Split predicates in affirmative sentences may be realized by a range of strategies.So-called “resultative compounds”, whereby a secondary or unmarked stative verb is conjoined with a main verb to form a compound, are extremely common in China,and are often preferred to equivalent periphrasis. The two members of such pairings are frequently separated by-de-(affirmative) and-bu-(negative). Some examples of these structures, also given in Bonta 2020, are shown following, with the stronger member of the pair shown in boldface:

tīng-de-dŏng

hear-POSSESSIVE-understand

‘hear and understand’ (often used instead of ‘understand’ when comprehension of a spoken utterance is referenced)

tīng-bu-míngbai

hear-NEGATIVE-understand

‘don’t [hear and] understand’

shuō-bu-tài-dìng

say-NEGATIVE-too-be definite

‘cannot say too definitely/for sure’

kàn-bu-jiàn

see-NEGATIVE-catch sight of

‘cannot see (i.e., I cannot catch sight of)’

chī-bu-xià

eat-NEGATIVE-go down

‘cannot get down any more (food)’

The designation of the second element as the strong element is motivated by the fact that it is this element that can be negated. Such a construction would thus be rendered in our proposed notation as:

Regarding such compounds, we have observed:

It should be plain that Chinese resultative compounds conform precisely to the pattern embodied by [12] as set forth by Peirce and clarified by Robertson: they involve the conceptual resolution of a single concept into two unequal parts, as with, e.g.,tīng-dedŏng, in which “understanding” is resolved into “hearing” (weak) and “understanding”(strong) orkàn-bu-jiàn, where “seeing” is resolved into “seeing” (weak) and “catching sight of” (strong). Unlike dilexemic, disyllabic words, these compounds do not constitute lexemic entries per se; rather, the formation of resultative compounds is a productive morphosyntactic process with many thousands of potential configurations. (Bonta, 2020)Further details concerning the formation of resultative compounds are also given in Bonta (2020).

Chinese also makes heavy use of adjectival predicates, as also described in great detail in Bonta (2020). For our purposes here, we simply note that adjectival predicates in Chinese can never appear without either a modifying adverb or aspectual particle. As a result,hăo, ‘[be] good/well’, can never be used with a simple subject,as, e.g., *wŏ hăo, ‘I am good’. Instead, some adverb of degree, likehĕn, ‘very’, orfēicháng, ‘really’, must be included, even if no strong degree is intended. Thus,wŏ hĕn hăomeans either ‘I am good’ or ‘I am very good’. On the other hand, we can saywŏ bu-hăo, ‘I am not good,’ orwŏ hăo-le, ‘I am fine’ (where-leis a particle denoting completion or presentness), because in these two cases, the adjectival predicate is clearly bipartite, consisting in the first instance of negative adverbial particlebu-+adjectival predicatehăo, and in the second, of adjectival predicatehăoplus aspectual particle-le. In every instance, we see that Chinese requires adjectival predicates to consist of two elements, the adjectival predicate per se and an adverb or aspectual particle.

Here, too, we see the operation of the positive constraint [+12] configuring Chinese predicates. In such cases, it is the modifying particle (hĕn,bu, orlein the aforementioned examples) that is serving as the weak (i.e., qualifying) element alongside the strong adjectival predicate:

To summarize, we have identified four morphosyntactic manifestations of [+12]in Chinese, one of which (the use of direct object incorporation and postverbs to split the Subject into two domains with different modes of association with the Predicate)is concerned with the Subject-Predicate relationship, and three of which (the use of affirmative-negative pairs for yes/no questions, the use of resultative compounds, and the requirement of a modifying element, whether adverb or aspectual particle, with adjectival predicates) are concerned with the structure of the predicate itself. Each of these four morphosyntactic manifestations of [+12] involve the construction of an unequal dichotomy. For additional clarity, they are shown together on Table 4:

Table 4. The unequal dichotomy [12] in Chinese morphosyntax

2.1.3 Chinese phonology

The realm of phonology, with its distinctive features and phonemes, has been relegated by many linguists and semioticians to asemiotic status; Hjelmslev’s meaningless “figurae”, of which phonemes and distinctive features were held to be prime examples, became the basis for the model of so-called double articulation of human language. But in the much more perceptive cadences of the Prague School tradition, the primordial components of language—distinctive features in particular—are indeed meaningful, albeit in an extremely inchoate sense, their semiotic force being derived mostly from “mere otherness” inherent in featural oppositions. Wrote Jakobson and Waugh:

The solesignatumof any distinctive feature in its primary, purely sense-discriminative role, is “otherness”: as a rule a change in one feature confronts us either with a word of another meaning or with a nonsensical group of sounds…. Distinctive oppositions have no positive content on the level of thesignatumand announce only the nearly certain unlikeness of morphemes and words which differ in the distinctive features used. The opposition here lies not in thesignatumbut in thesignans: phonic elements appear to be polarized in order to be used for semantic purposes. Such a polarization is inseparably bound to the semiotic role of distinctive features. (Jakobson & Waugh, 1979, p. 47)

Phonemes, which are derived from the distinctive features, may be held to be more meaningful, i.e., less semiotically vague, while still falling far short of the assertive precision of propositions and other full-fledged instantiations of language. Yet if these primordial features of language are indeed semiotic, then we would expect the Categories to be manifest in their workings, just as has proven to be the case elsewhere. Having already shown evidence for the consistency of semiotic structuring in the lexicon, morphology, and syntax in Chinese, we predict that the conditioning constraints [-3] and [+12] are operative at the phonological level also. But in order to test this, we first need to consider in what ways the Categories might be manifest in phonology.

In general, phonology would appear to be a domain where Firstness preponderates.The distinctive features are in effect qualities of sound that shape phonemes and their allophones. But even here, phonemes per se are abstractions conventionalized by habits of mind, and so also embody Thirdness to a considerable degree; they are,in effect, very inchoate Symbols that give rise to Indexes (allophones), the phonetic existents that our physical senses perceive and interpret.

While languages display an enormous variety of phonemic possibilities, one universal contrast above all others divides phonemes into two broad domains:consonants and vowels. All languages have this contrast, and while every language has a different inventory, the essential contrasts between these two broad classes of sound are the same everywhere: whereas vowels tend to be continuous, pure voice,and very energetic, consonants (or at least, those that contrast maximally with vowels)tend to be voiceless, non-continuous, and reliant for their force on articulation rather than pure sound energy. In this way, the opposition between consonant and vowel generates syllables that the mind assembles into meaningful constituents.

Another contrast between vowels and consonants lies in their capacity to communicate meaning. In many Indo-European and Semitic languages particularly,consonants seem to bear most of the semiotic “load”, whereas vowels exist primarily to “color” words. That this is so is evidenced, among other things, by the fact that the abstractions we call “roots” in these languages are premised on consonants, not vowels, by the fact that so-called “phonaesthemes” (see discussion of these fascinating entities in Jakobson & Waugh, 1979) depend for their force on consonantal, and not vocalic, configurations (such as the well-known fact that, in English, many words beginning with the consonant clusterstr-denote long, thin objects), and by the fact that, in such languages, a passage with all its vowels deleted remains largely comprehensible, but not the reverse.

By contrast, vowels are frequently varied to denote changes in modality and tense,as with ablaut, or lengthened in speech to denote emphasis, incredulity, or some other affective coloring (as in, ‘You did whaaaat?’).

Facts such as these suggest that, potentially at least, it is consonants that bear the primary capacity for symbolic representation/[3], whereas vowels are primarily affective/[1]. Consonants, after all, would seem to require greater mental effort to produce, involving, as they do, conscious manipulation of tongue, lips, teeth, etc.,in conjunction with various areas of placement in the mouth, from the alveolar ridge to the velum, uvula, and even glottis. This is the reason that purely involuntary vocalizations (screams, gasps, groans, and the like) representing emotional states like pain, fear, pleasure, surprise, etc., tend to be vocalic—simple expulsions of breath across vibrating vocal cords. These are universal—a scream of pain or expression of surprise sound much the same across languages—and all are denotative of states that approximate Firstness.

However, this contrast between consonants and vowels, as to their semiotic freighting, is not at all evident in Chinese—and indeed, in many other language groups outside of the domain of Indo-European and Afro-Asiatic. In English, as we have already seen, the allowable number of syllables is much higher than in Chinese,and this is owing to the much greater number of allowable consonant configurations,including consonant clusters. Chinese, by contrast, allows few true consonant clusters,and those that it does allow typically involve a nasal or liquid + consonant, where nasals (/n/ and /m/) and liquid /r/ are among the least consonant-like of all consonants,and in many languages, are grouped with vowels. Moreover, consonant clusters within lexemes are not found, such that the canonical Chinese syllable, excluding the tone, is of the form (C)V(C), with only /n/, /r/, and /ŋ/ eligible as lexeme-final consonants. As a result, even across lexical boundaries, allowable sequences of C+C are extremely limited in Chinese. More complex consonant clusters of three entries, like-spr-and-ndr-, are completely excluded in all phonotactic environments.

This being the case, in contrast to English and many Indo-European languages, the meaning of a passage of Chinese (written in pinyin or Romanized phonologic script)with vowels removed would, in all likelihood, be completely opaque.8The absence of consonant complexes carrying the semiotic freight, therefore, may be characterized as the negative constraint [-3] operating at the phonological level (in this case, in the domain of phonotactic rules).

To discern the operation of the positive [+12] constraint at the level of Chinese phonology, we consider first how languages create meaningful sound, in general. The underlying operative principle both in the construction of phonemes from distinctive features and in the assembly of morphemes from phonemes is contrastive opposition.With phonemes, as we have already seen, the “mere otherness” of distinctive features provides for the differentiation of one phoneme from another; from the perspective of acoustic phonology, set forth by Jakobson and the Prague School, these features are represented in terms of paired opposites, such as compact/diffuse, grave/acute, and strident/mellow. The advantage of the acoustic approach is that such features may be realized in a variety of articulatory contexts; they represent a generalization and simplification of the very large ensemble of attested articulatory features.

Not only that, these opposing pairs give rise to phonemes which, in turn, rely upon another fundamental contrast—the opposition of vowel and consonant—to produce actual language. For European languages, these two layers of opposition suffice to create lexical and grammatical meaning, with other redundant features, including tone, constitutive of discourse modalities.

In Chinese, an additional dimension is required to complete the transition from inchoate sound structures to meaningful speech: sense-determinative tones. Every syllable in Chinese, as we have seen previously, is a lexeme, and therefore, every Chinese lexeme has one and only one vowel or diphthong, and a single corresponding tone.9Unlike phonemes and their distinctive features, Chinese tones cannot be represented in terms of a matrix of oppositions. Their primordial meaning, as well as the sense in which they are applied to consonant-vowel configurations to instantiate lexemes, is not otherness but suchness. And this pairing of otherness with suchness is akin to pairing resistance/[2] with quality/[1] to achieve phonic completeness. As we have elsewhere suggested, this pairing is an unequal one, with the tone conceptually subordinate to the phoneme, as evidenced by the fact that tones may be lost in the second entry of disyllabic words, but not phonemes; by the fact that every Chinese lexeme perforce consists of an array of phonemes and distinctive features, but only a single tone; and by the fact that in Chinese, as in all other attested languages, puns,rhebuses, and the like rely for their significative force on phonemic similarity, and not on tonal similarity; and on the fact that, even in environments where tones cannot be discerned (songs, e.g.), words are still meaningful. Thus the structure of Chinese at the phonological level involves a dichotomy pairing the stronger, opposition-based operations of phonemes and their distinctive features with the weaker, qualitative modalities of the tones, [+12] embodied at the most elemental levels of linguistic signification.

What we have seen, then, is that the operation of the positive constraint [+12] and its negative concomitant [-3] are both present and pervasive at every level of Chinese that we have examined. Nor are these instances cherry-picked; they represent the entire range of Chinese typological distinctives, from tones to yes-no questions. While more thorough scrutiny of Chinese will of course yield exceptions, we anticipate that they will be far fewer than would ordinarily be the case with a language more susceptible to admixture with foreign influences (including semiotic imports). But with semiotics, we must not equate theoretical rigor with exceptionless results;we instead seek general, unmistakable trends consistently manifest in core, not peripheral, domains of a given semiotic landscape, and we are confident that, in the case of Chinese, we have found an abundance of such trends, all of which conform to a singular pair of primordial Categorial semiotic constraints.

To summarize, we have found the following evidence of the operation of the positive conditioning constraint [+12] and the negative conditioning constraint [-3] in Mandarin Chinese:

[+12]:

Morphosyntax:

● Multiple arguments (of complex or polyadic Subjects) related to Predicate via both contiguity and blending

● Predicates split according to pattern X-not X

● Verbs represented as double lexemes with–de-/-bu-interposed

● Adjectival predicates must include a second or complementary syllable,lexeme, or word, such asbu-, -le,orhěn.

Lexicon:

● Disyllabic/dilexemic words are the rule

Phonology:

● Pairing of “suchness”/[1] of tonal features with “otherness”/[2] of distinctive features

[-3]:

Morphosyntax:

● Absence of agreement morphology

● Near-absence of overt plural marker

Lexicon:

● All lexemes monosyllabic, with extremely high number of homophones owing to very limited set of allowable syllables

Phonology:

● Very limited inventory of consonants and consonant clusters

We now seek to adapt this method, mutatis mutandis, to several other languages in which semiotic structural constraints other than [+12] are prominent.

2.2 Sora and [1]

Pure Firstness/[1] as a semiotic structural constraint is often a characteristic of aboriginal cultures, as previously described in considerable detail elsewhere(Bonta, 2018). In general, we observed that so-called polysynthesis, the capacity of many aboriginal languages around the world to create “sentence-words”,is a morphosyntactic manifestation of [1]. That this is so can be envisaged in several different ways. For one thing, the merging of subject and predicate via the incorporation of grammatical subjects, direct objects, indirect objects, and other arguments of the predicate into a single indissoluble lexemic compound is typical of what we have elsewhere styled blending, namely, the strategy of idea association whereby subject and predicate (in the Peircean sense of the terms) are simply melded together into a whole. Such a strategy dispenses altogether with the Secondness of deixis and indexicality, which must be invoked wherever discrete lexemes are brought into mere juxtaposition. It is equally exclusionary of agreement, whereby meaningful association is achieved by inflectional morphology harmonizing one term with another (as with subject-verb agreement). Otherwise put, this strategy tends toward the representation of propositions as unitary morphosyntactic strings, in which the complementarity of Subject and Predicate is not represented by any kind of structural separation.