Association between oral contraceptive use and pancreatic cancer risk: A systematic review and metaanalysis

Milena Ilic, Biljana Milicic, Irena Ilic

Abstract

Key Words: Pancreatic cancer; Oral contraceptives; Risk factors; Risk assessment; Metaanalysis; Review

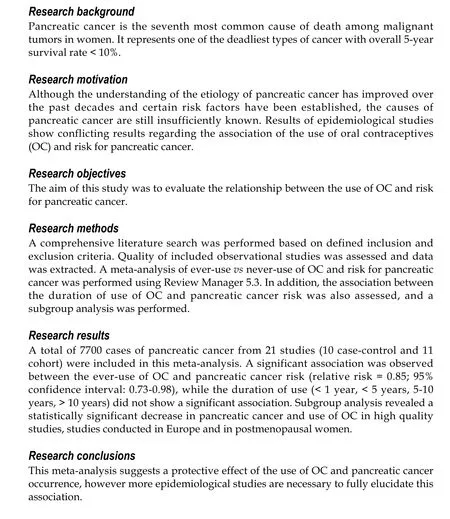

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is the seventh most common cause of death among malignant tumors in females, with about 220000 deaths worldwide in 2018 [1 ,2 ]. Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest types of cancer, with an estimated overall 5 -year survival rate less than 10 %[1 ]. Pancreatic cancer mortality is characterized by a dramatic increase after the age of 30 years, reaching the highest burden in women at about 80 -yearsold[1 ,3 ].

An understanding of the etiology of pancreatic cancer has improved dramatically over the past decades and certain risk factors have been established including tobacco use, obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic pancreatitis, positive family history and inherited genetic syndromes, high alcohol consumption, dietary factors, physical inactivity, workplace exposure to some chemicals, infections[4 -7 ]. Although some risk factors have been identified, the causes of pancreatic cancer are still insufficiently known.

Regarding the link between pancreatic cancer risk and oral contraceptive (OC) use,epidemiological studies have shown conflicting results: Some findings have shown positive associations with risk of pancreatic cancer[8 ,9 ], whereas some studies have indicated inverse associations[10 ,11 ]. One previous meta-analysis of observational studies did not support the hypothesis that OC use is associated with pancreatic cancer risk (the pooled relative risk [RR] = 1 .09 , 95 % confidence interval [CI]0 .96 -1 .23 )[12 ].

A better understanding of risks of pancreatic cancer occurrence in women who use OC may be relevant for pancreatic cancer prevention strategy. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between the use of OC and pancreatic cancer risk by performing a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This meta-analysis was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines[13 ].

Ethics statement

This study is a part of a research project approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Kragujevac (No. 01 -14321 ).

Literature search

We searched PubMed from inception through December 2020 using combinations of keywords: (“oral contraceptives” or “birth control pills”) and (“pancreatic cancer” or“pancreatic tumor” or “pancreatic neoplasm”) and (“risk” or “risk factors” or “risk assessment”). Additionally, references of retrieved studies and reviews were handsearched to identify additional relevant studies (up to 31 December 2020 ). No language restrictions were applied in the search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two authors (II and MI) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies retrieved by literature search. Subsequently, the full texts of articles that were identified as relevant were assessed. Any disagreements between the reviewers were resolved through consensus. Studies which reported on the association between the use of OC (the exposure of interest) and risk of pancreatic cancer (the outcome of interest) and that were designed as case-control studies and cohort studies were included. In cases of multiple publications reporting results from the same population,the most recent report and the one with the most data was used. Case reports, caseseries, reviews, letters, animal studies and studies with incomplete data were excluded. Studies that did not report separate data for OC use, but instead reported“any hormone therapy” were excluded.

Data extraction and quality appraisal of included studies

Data extraction and quality appraisal were performed independently by two authors(II and MI). Details regarding the study’s author and year of publication, study design,sample size, methods of exposure assessment, methods of outcome assessment, and main findings regarding the investigated outcome were extracted. Methodological quality of studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for quality assessment of case-control studies and cohort-studies[14 ]. This tool rates three categories: Selection, comparability and exposure (in case-control studies) or outcome(in cohort studies) in observational studies using a star-system. We considered studies with 8 and 9 stars as high quality, 6 and 7 stars as medium quality, and ≤ 5 stars as low quality.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis of the comparison of nonusersvsusers of OC was performed. Odds ratios (ORs), RRs, and hazard ratios (HRs) were extracted from included studies and transformed into RRs. It can be considered that OR and HR approximate RR because the absolute risk of pancreatic cancer is low[15 ]. For studies that did not report risk estimates for the comparison of evervsnever use of OC, we calculated ORs and RRs based on the available published data. We pooled risk estimates for pancreatic cancer and calculated overall RRs with 95 %CIs. Risk effects were combined using the random-effects model[16 ]. The P < 0 .05 was considered significant.

Heterogeneity was quantified using Cochran’s chi-square test and I2statistic, with I2 values of 30 %-60 %, 50 %-90 %, and 75 %-100 % indicating moderate, substantial and considerable heterogeneity, respectively[17 ]. To explore heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analyses by study design (case-control and cohort), source of controls in case-control studies (population and hospital), number of cases of pancreatic cancers(< 200 and ≥ 200 ), and assessed study quality (NOS score ≤ 7 and > 7 ), geographical region (Europe, Americas, Asia), and menopausal status (premenopausal and postmenopausal). Statistically significant subgroup differences were considered forP< 0 .1 [18 ].

The pooled RRs with corresponding 95 %CIs were presented graphically with forest plots. Publication bias was assessed with a funnel plot. All statistical analyses were performed using Review Manager 5 software (RevMan version 5 .3 , The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration)[19 ].

RESULTS

Literature search results and characteristics of included studies

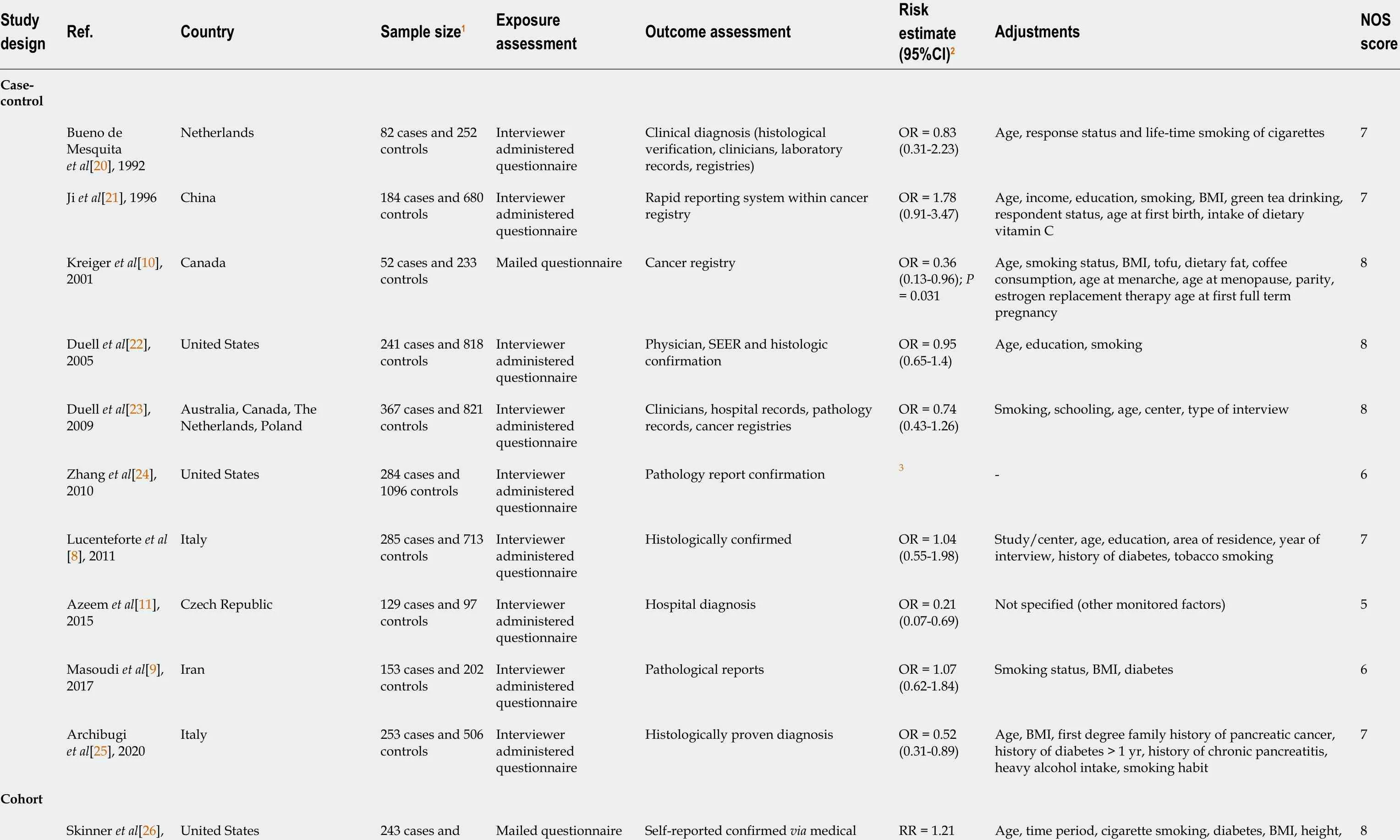

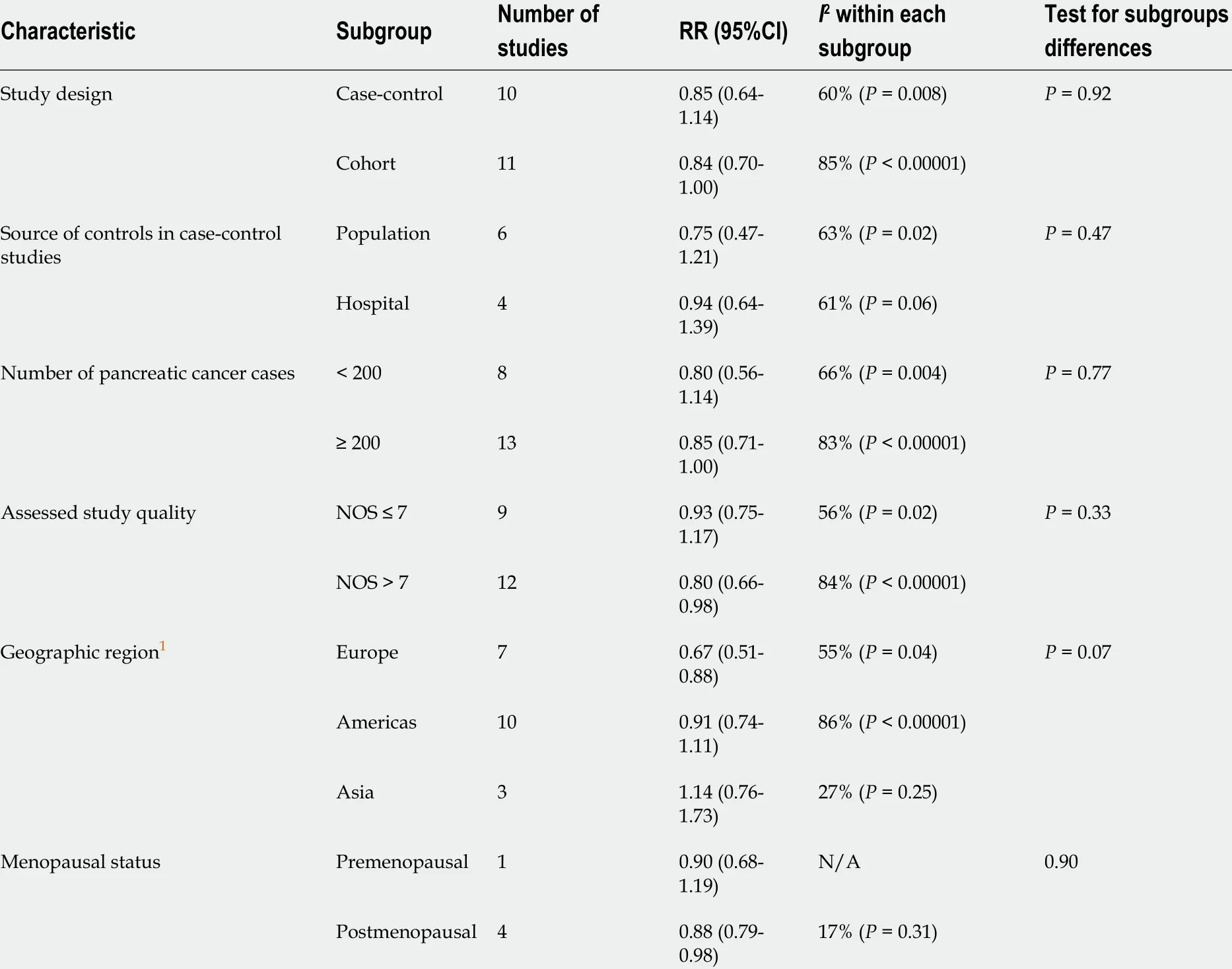

The results of the literature search are presented in Figure 1 . We identified 21 studies that investigated the association between the use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer and that fulfilled the inclusion criteria[8 -11 ,20 -36 ]. There were 10 case-control studies and 11 cohort studies included in the meta-analysis. Characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 1 . In total, the included studies comprised 7700 cases of pancreatic cancer. Among the case-control studies, six had population-based controls and four had hospital based-controls. The use of OC was assessedviainterviews with trained interviewers in 11 studies by means of self-reported questionnaires in 9 studies, and one study used data from the National Register of Medicinal Products.Outcome assessment was verified through cancer and hospital registries, and in most of the studies, there was pathohistological verification of the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Seven studies were conducted in the European region, ten in the Americas (the United States and Canada), three in Asia, and one study was multicentric and conducted in all three regions. According to NOS scores, 12 studies were of high quality (3 case-control and 9 cohort), 8 of moderate quality (6 case-control and 2 cohort), and 1 case-control study was of low quality.

Ever use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer

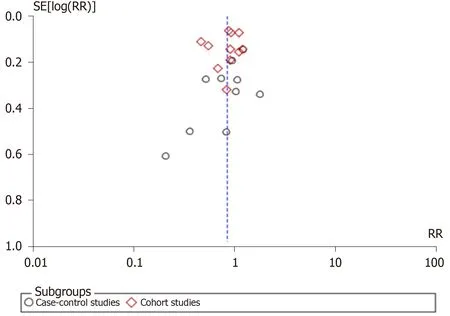

Pooled risk estimates of all included studies showed that the ever use of OC was statistically significantly associated with a decreased risk of pancreatic cancer (RR =0 .85 , 95 %CI: 0 .73 -0 .98 ; P = 0 .03 ) (Figure 2 ). There was substantial heterogeneity for this estimate (I2= 78 %; P < 0 .00001 ). Pooled risk estimates from case-control studies were not statistically significant (RR = 0 .85 , 95 %CI: 0 .64 -1 .14 ), while the association between ever use of OC and decreased risk of pancreatic cancer was borderline significant in cohort studies (RR = 0 .84 , 95 %CI: 0 .70 -1 .00 ). Visual inspection of funnel plot (Figure 3 )did not indicate any apparent presence of publication bias.

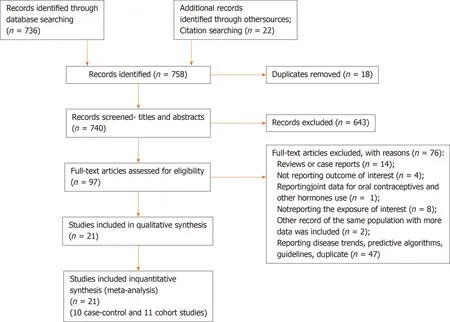

Duration of OC use and risk of pancreatic cancer

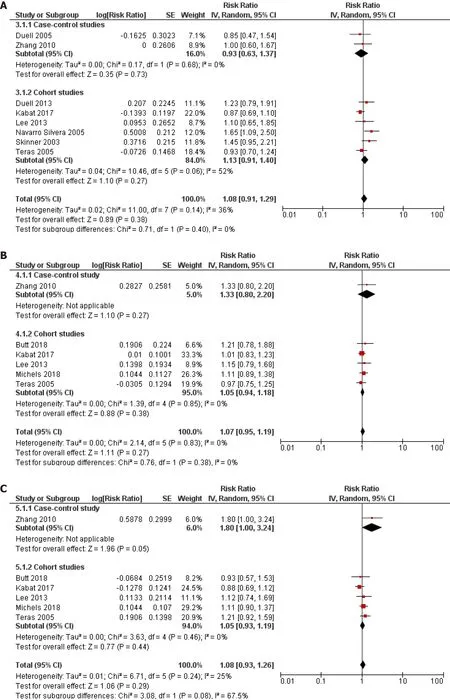

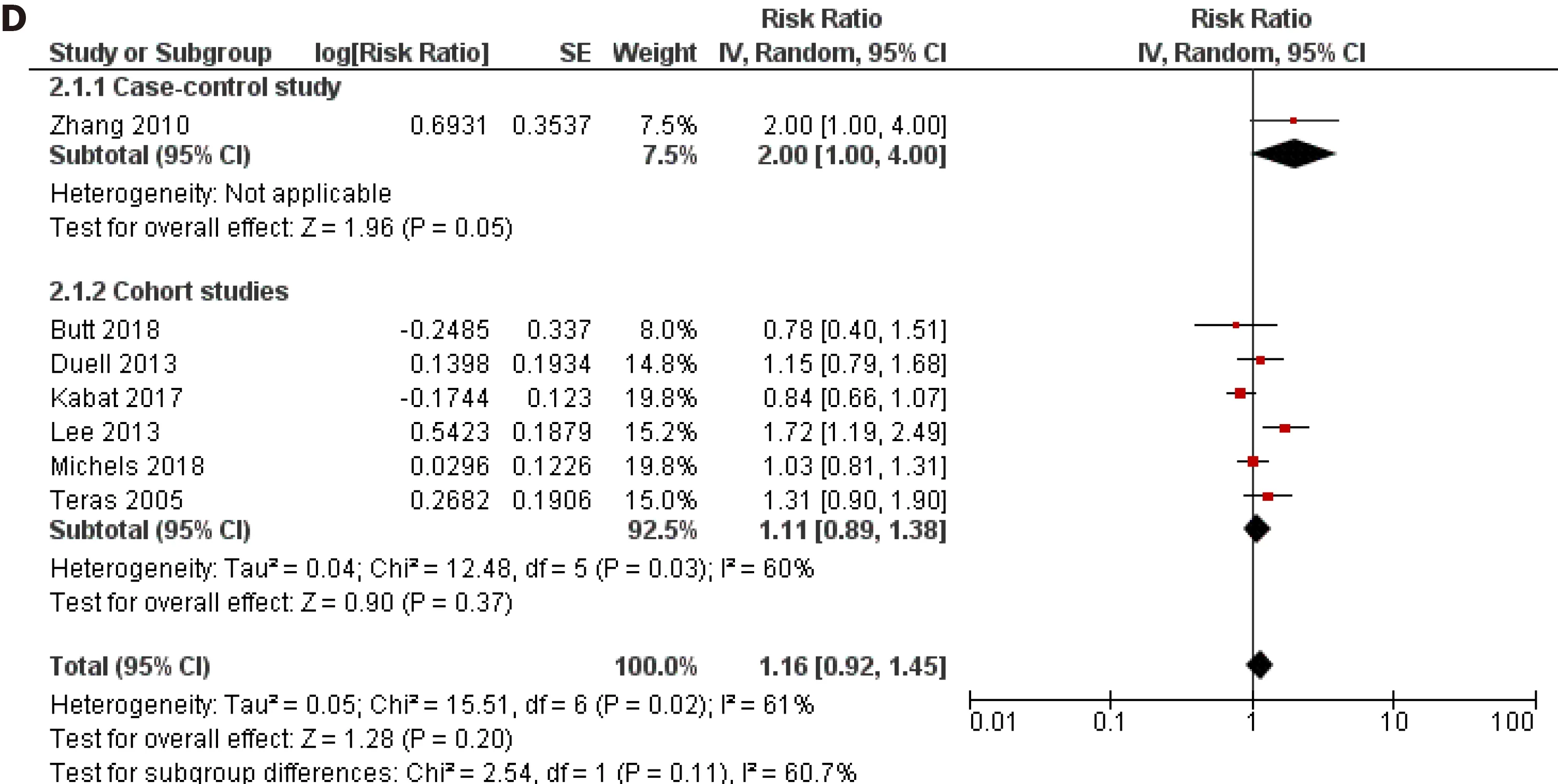

Ever usevsnever use of OC was chosen as the primary assessment of exposure because some studies have reported that it was not possible to assess the years of oral contraceptive use in their sample[10 ] or simply did not inquire participants about the duration of use[8 -11 ,23 ,29 ,34 ]. However, we pooled the results from the subset of studies that investigated the duration of use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer and that reported comparable cut-off periods. Eight studies (2 case-control and 6 cohort)assessed the < 1 year duration of OC use and risk of pancreatic cancer and the pooled risk estimate was not statistically significant (RR = 1 .08 , 95 %CI: 0 .91 -1 .29 ; P = 0 .38 )(Figure 4 A). Similarly, across one case-control and six cohort studies, the results were not significant for durations of use: < 5 years (RR = 1 .07 , 95 %CI: 0 .95 -1 .19 ; P = 0 .27 )(Figure 4 B), 5 -10 years (RR = 1 .08 , 95 %CI: 0938 -1 .26 ; P = 0 .29 ) (Figure 4 C) and > 10 years (RR = 1 .16 , 95 %CI: 0 .92 -1 .45 ; P = 0 .20 ) (Figure 4 D).

Subgroup analyses

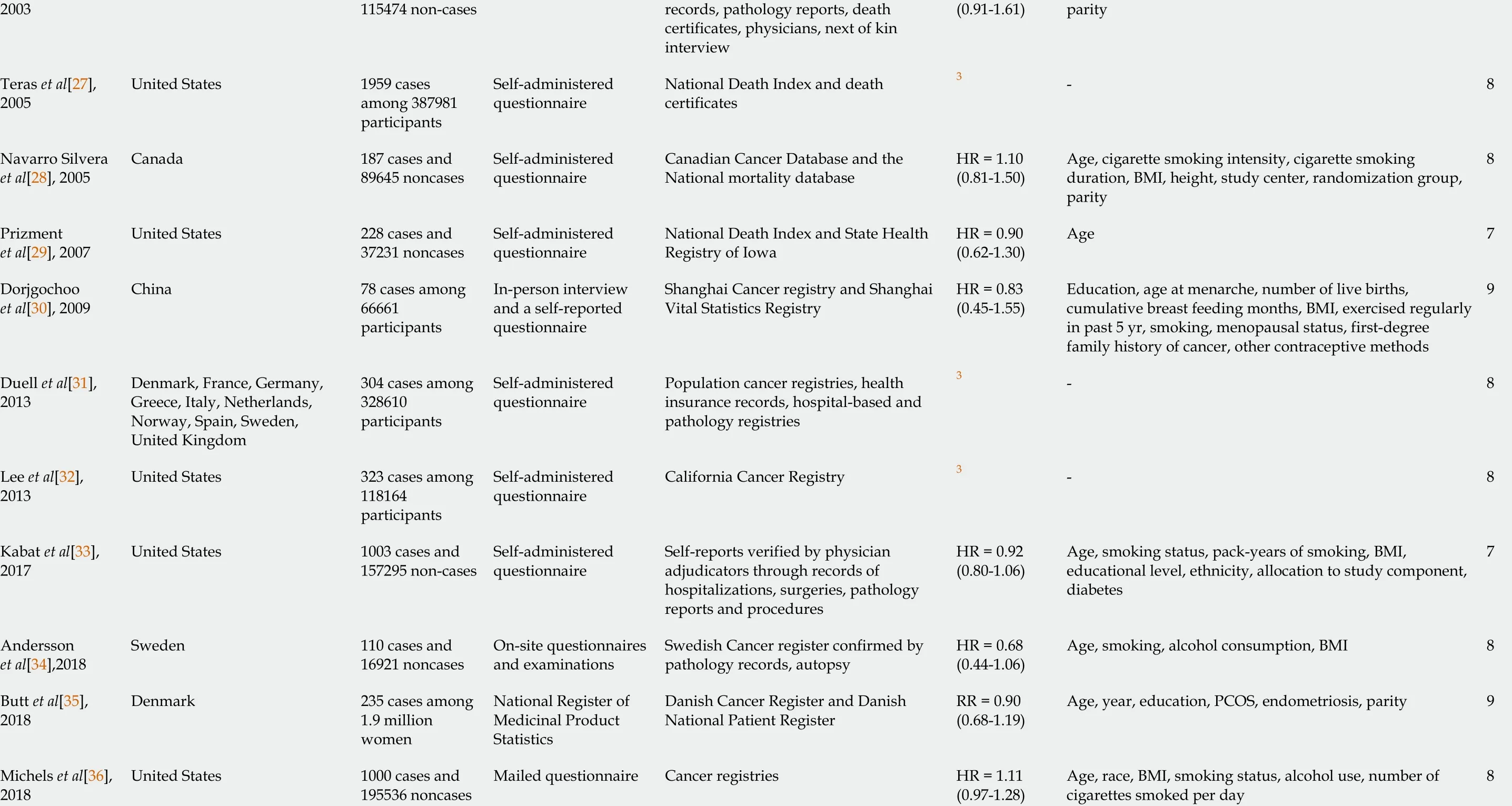

Results of the subgroup analyses by selected characteristics are presented in Table 2 .Statistically significant results for subgroup differences were noted only for geographic region (EuropevsAmericasvsAsia) where studies were conducted (P=0 .07 ), while there were no significant subgroup differences noted for study design(case-controlvscohort studies), source of controls in case-control studies (populationvshospital), number of pancreatic cancer cases (< 200 vs ≥ 200 ), study quality (NOS ≤ 7vsNOS > 7 ), or menopausal status (premenopausalvspostmenopausal). Finally,subgroup analyses revealed a statistically significant association between the use of OC and decreased risk of pancreatic cancer in studies of high quality (RR = 0 .80 ,95 %CI: 0 .66 -0 .98 ; P = 0 .03 ), studies conducted in Europe (OR = 0 .67 , 95 %CI: 0 .51 -0 .88 ;P= 0 .004 ) and in postmenopausal women (r = 0 .88 , 95 %CI: 0 .79 -0 .98 ; P = 0 .02 ).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we identified 10 case-control and 11 cohort studies that investigated the association between the use of OC and pancreatic cancer. Our pooled analysis of these 21 studies, which comprised 7700 cases of pancreatic cancer, showed that the ever use of OC was statistically significantlyassociated with a decreased risk of pancreatic cancer. However, the association was not significant when the duration of OC use less than 1 year, less than 5 years, 5 -10 years, and longer than 10 years was assessed in relation to pancreatic cancer risk. Asignificantly reduced risk of pancreatic cancer in women using OC was noted in higher quality studies, studies conducted in Europe, and in postmenopausal women.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

1 For samples including both sexes only data for women were presented.2 Ever use of oral contraceptives vs never use.3 Not reported, derived from available published data.CI: Confidence interval; NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale; OR: Odds ratio; RR: Relative risk; HR: Hazard ratio; BMI: Body mass index; PCOS: Polycystic ovary syndrome.

Table 2 Association between the use of oral contraceptives and risk of pancreatic cancer: Subgroup analysis

Differences in pancreatic cancer incidence rates between sexes, namely a higher incidence of pancreatic cancer in men than in women[7 ], have led to investigations into possible reasons behind these differences. Apart from the possible influence of environmental factors, it was hypothesized that female sex hormones could be responsible for a lower incidence of pancreatic cancer in women.In vitroandin vivostudies have shown that the pancreas contains estrogen and androgen receptors and that estrogen inhibits and testosterone promotes the occurrence of some pancreatic cancers[37 ].

Numerous observational studies have investigated the role of the use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer; however, the results were not consistent. While some authors have reported an inverse relationship between the use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer[10 ,11 ,25 ,31 ,32 ], other studies have not confirmed these findings. However, none of the published studies found a significant positive relationship between the ever use of OC and pancreatic cancer. With regard to the duration of OC use, our pooled analyses did not identify a significant association with pancreatic cancer risk. Still, one cohort study revealed a significant increase in pancreatic cancer risk in women using OC < 1 year (HR = 1 .65 , 95 %CI: 1 .08 -2 .50 )[28 ], but the number of cases of pancreatic cancer in the group of women who were taking OC less than 1 year was small. Also,one hospital-based case-control study (NOS score assessed as 6 ) found a borderline positive association for the duration of use of OC of 5 -10 years and > 10 years and risk of pancreatic cancer[24 ], and, despite the small numbers of cases in these groups, thePfor trend was significant (< 0 .01 ). In contrast, Kreiger et al[10 ] found a significant decrease in pancreatic cancer risk in women using OC longer than 6 mo. These discrepancies in results across the studies might be explained by differences in study design, study population, assessment of exposure assessment, definitions of exposure,and different cut-offs for duration of use of OC. Additionally, most of the studies have reported risk estimates adjusted for known and potential pancreatic cancer risk factors(age, diabetes, cigarette smoking, obesity), but with fewer studies also providing estimates adjusted for history of pancreatitis, positive family history of pancreatic cancer and high level of alcohol consumption[25 ,30 ,34 ,36 ] and one study reporting estimates adjusted only for age[29 ]. While some of the included studies have adjusted for factors which refer to diet, this most often involved body mass index(BMI)[9 ,10 ,21 ,25 ,26 ,28 ,30 ,33 ,34 ,36 ], with only two studies investigating nutrition variables such as green tea drinking and intake of dietary vitamin C[21 ], and coffee and tofu consumption and dietary fat intake[10 ]. Obesity is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer; however, the mechanisms are not fully known and may involve sex hormones[21 ]. High BMI might reflect high intake of dietary fat, although the findings regarding its association with pancreatic cancer risk are inconsistent[21 ,34 ]. Notably,adipose tissue produces estrogens and might have a protective role[34 ]. Therefore,dietary factors could confound the association between the risk for pancreatic cancer and the use of OC[10 ]. Similarly, studies investigating nutrition and pancreatic cancer risk should adjust for reproductive factors such as the use of OC.

Figure 1 Flow-diagram of literature search.

Subgroup analyses identified a significantly lower risk of pancreatic cancer in women in European region who used OC (RR = 0 .67 , 95 %CI: 0 .51 -0 .88 ). Worldwide,highest incidence of pancreatic cancer in women was noted in Northern America,Western and Northern Europe[7 ]. Prevalence of OC use was the highest in Northern America, followed by Europe and Asia at 75 %, 69 % and 68 %, respectively[38 ]. The differences in pancreatic cancer risk associated with the use of OC between different geographic regions could be explained by differences in exposure to environmental risk factors, genetic or cultural differences. Notably, most of the studies pooled in this meta-analysis have included relevant known or potential risk factors as covariates in the adjustments of risk estimates. It is also possible that regional differences in diagnosis and outcome assessment and reporting could contribute to the observed significant difference in subgroup analyses by geographic region. Possible explanations for the observed inverse relationship between the use of OC and pancreatic cancer in postmenopausal women could be related to the age of menopause, duration of menopause, duration of use of OC, and formulation of used OC.

Figure 3 Funnel plot of studies investigating the use of oral contraceptives and risk of pancreatic cancer. RR: Relative risk.

Our literature search revealed one previously published meta-analysis that assessed the association between pancreatic cancer risk and female hormonal and menstrual factors[12 ], and one pooled analysis from the international pancreatic cancer casecontrol consortium[39 ]. In contrast to our results, a previous meta-analysis found no significant associations between the risk of pancreatic cancer and OC use-pooled RR from six case-control studies and eight cohort studies was 1 .09 (95 %CI: 0 .96 -1 .23 )[12 ].Subsequently, the authors noted that their subgroup analyses by study design showed a marginally significant increased risk of pancreatic cancer associated with OC use in cohort studies (RR = 1 .09 , 95 %CI: 1 .00 -1 .29 ). Our subgroup analyses by study design identified the opposite, namely, a borderline insignificant result for inverse association(RR = 0 .84 , 95 %CI: 0 .70 -1 .00 ). However, the authors identified publication bias for studies on exposure to OC, which could mask the true association. Our meta-analysis included an additional 4 case-control studies and 3 cohort studies, totaling 7700 cases of pancreatic cancervs5084 in the previous meta-analysis, and our analysis did not identify publication bias. Also, our study did not have language limitations in the literature search in contrast to previously conducted meta-analyses. A previous metaanalysis did not assess the quality of included studies, unlike our study that also explored subgroup differences in relation to study quality and found a statistically significant reduction in pancreatic cancer risk associated with the use of OC (RR = 0 .67 ,95 %CI: 0 .51 -0 .88 ) when pooling results from studies of high quality. The previous pooled analysis that included only case-control studies did not find a significant association between the ever use of OC and pancreatic cancer (OR = 0 .83 , 95 %CI: 0 .69 -1 .01 ).

Figure 4 Forest plot of the association between pancreatic cancer risk and duration of oral contraceptives use. A: Less than 1 year; B: Less than 5 years; C: 5 -10 years; D: Longer than 10 years. CI: Confidence interval.

Finally, studies included in this meta-analysis have been conducted in different time periods and the influence of different formulations of OC cannot be excluded.However, only one of the included studies inquired about the type of OC used by women[35 ], and did not find a significant association between pancreatic cancer and use of different types of hormonal contraceptives (RR = 0 .92 , 95 %CI: 0 .62 -1 .36 for oral combined 20 -40 ug ethinyl estradiol, and RR = 1 .16 , 95 %CI: 0 .71 -1 .89 for progestin only). Further on, two studies made assumptions regarding the dose of OC by using the calendar year of use as a proxy for whether women were taking high-dose or low dose formulations[32 ,34 ]. Andersson et al[34 ] did not find a significant association between the risk of pancreatic cancer and use of OC in 1960 -1970 , after 1970 , 1960 -1980 or after 1980 . However, Lee et al[32 ] found that a duration dose was present for highdose use of OC (women who stopped using OC before 1974 , P for trend 0 .027 ), and in particular the risk for pancreatic cancer was increased in women using high-dose OC ≥10 years (RR = 2 .08 , 95 %CI: 1 .05 -4 .12 ). Due to the inconsistent results obtained by casecontrol and cohort studies, it is important to address this issue when planning future observational studies in order to provide further insight into the association between the use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this represents the most comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies which have investigated the association between the use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer to date. Our analysis included 21 published studies with 7700 from various geographic regions which could add to the generalizability of the presented results. Also, the quality of included studies was relatively high and assessment of outcome involved pathohistological confirmation in majority of the cases.

However, our study had several limitations. First, this was a meta-analysis of observational studies and inherit limitations of study design of included studies cannot be excluded. Second, assessment of exposure was mostly based on self-report or obtained through interview, with only one study investigating the use of OC through a national medicinal registry. Further on, even though we applied a randomeffects model in our meta-analyses, a high level of heterogeneity was found in some comparisons in our analyses, which we tried to explore by performing subgroup analyses. We did not assess the association between pancreatic cancer and age at initiation of OC use, years since last use and intensity of use because only two studies reported this data and used different cut-offs. Our analyses pooled risk estimates adjusted for most potential cofactors as available in original studies, however it is not possible to exclude the influence of some confounding factors. Namely, the use of OC could be related with a higher socio-economic status which can in turn be related to a healthier diet[25 ]. Presence of bias due to the lack of confounding control cannot be excluded in included studies which have not considered dietary factors as possible confounding factors when investigating the association between the use of OC and risk for pancreatic cancer. Further on, for a few studies for which we needed to derive the necessary risk estimates there were no available adjusted risk estimates. Finally, an analysis of individual-patient data would have provided more precise results regarding the association between the use of OC and risk of pancreatic cancer.

CONCLUSION

Ever use of OC was associated with a decreased risk of pancreatic cancer in the present meta-analysis. However, more well-designed and detailed epidemiological studies are necessary in order to fully elucidate the association between the use of OC and pancreatic cancer.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research perspectives

Further epidemiological studies are warranted to fully assess the association between the use of OC and risk for pancreatic cancer. These future studies investigating the risk for pancreatic cancer should be well-designed and include detailed questions regarding the use of OC.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年20期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年20期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: A narrative review

- Cyclophosphamide-associated enteritis presenting with severe protein-losing enteropathy in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: A case report

- Breakthroughs and challenges in the management of pediatric viral hepatitis

- Understanding celiac disease monitoring patterns and outcomes after diagnosis: A multinational,retrospective chart review study

- Evolving role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease: Going beyond diagnosis

- Role of modern radiotherapy in managing patients with hepatocellular carcinoma