The effectiveness of a 17-week lifestyle intervention on health behaviors among airline pilots during COVID-19

Daniel Wilson,Matthew Driller,Ben Johnston,Niholas Gill

a Te Huataki Waiora School of Health,The University of Waikato,Hamilton 3216,New Zealand

b Faculty of Health,Education and Environment,Toi Ohomai Institute of Technology,Tauranga 3112,New Zealand

c Sport and Exercise Science,Human Services and Sport,La Trobe University,Melbourne 3086,Australia

d Aviation and Occupational Medicine Unit,Wellington School of Medicine,Otago University,Wellington 6242,New Zealand

e New Zealand Rugby,Wellington 6011,New Zealand

Abstract Purpose:The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of a 17-week,3-component lifestyle intervention for enhancing health behaviors during the coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19)pandemic. Methods:A parallel-group(intervention and control)study was conducted amongst 79 airline pilots over a 17-week period during the COVID-19 pandemic.The intervention group(n=38)received a personalized sleep,dietary,and physical activity(PA)program.The control group(n=41)received no intervention.Outcome measures for sleep,fruit and vegetable intake,PA,and subjective health were measured though an online survey before and after the 17-week period.The changes in outcome measures were used to determine the efficacy of the intervention. Results:Significant main effects for time×group were found for International Physical Activity Questionnaire-walk(p=0.02)and for all other outcome measures(p<0.01).The intervention group significantly improved in sleep duration(p<0.01;d=1.35),Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score(p<0.01;d=1.14),moderate-to-vigorous PA(p<0.01;d=1.44),fruit and vegetable intake(p<0.01;d=2.09),Short Form 12v2 physical score(p<0.01;d=1.52),and Short Form 12v2 mental score(p<0.01;d=2.09).The control group showed significant negative change for sleep duration,Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index score,and Short Form 12v2 mental score(p<0.01). Conclusion:Results provide preliminary evidence that a 3-component healthy sleep,eating,and PA intervention elicit improvements in health behaviors and perceived subjective health in pilots and may improve quality of life during an unprecedented global pandemic.

Keywords:COVID-19;Healthy eating;Lifestyle health;Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity;Sleep

1.Introduction

The global coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19)pandemic has rapidly spread,showing capability to infect the world’s population.1Widespread infectious diseases such as COVID-19 are associated with adverse mental health consequences2and perturbations in physical activity(PA)behaviors due to environmental factors such as forced self-isolation.3The confinement of individuals to their homes may increase sedentary behavior4and has a direct impact on lifestyle,and,consequently,on sleeping,eating,and PA patterns.5Furthermore,psychological and emotional responses to the pandemic6may lead to dysfunctional dietary and sleep behaviors.7,8Numerous industries have experienced substantial operational perturbations emanating from COVID-19,including civil aviation.9Consequently,these conditions may have unexplored impacts on the health behaviors of airline pilots.Vocational requirements of airline pilots present health risks,such as circadian disruption due to shift work and flight schedules,10fatigue induced by flight schedules,11irregular meal times,mental stress demands associated with flight safety,12and the sedentary nature of the job.13Circadian disruption is detrimental to acute physiological14and psychological15health metrics and is associated with elevated risk for some chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease.16Despite reduced workloads for airline pilots during COVID-19,9substantial industry disruption,uncertainty,17and financial concerns confounded by lockdown conditions may present adverse effects on the physical3,18and mental health19of pilots.

Obtaining adequate sleep,consuming enough fruits and vegetables,and engaging in sufficient PA are 3 lifestyle behaviors that significantly reduce all-cause mortality20-22and have a positive effect on physical and mental health.23,24Good sleep health facilitates the ability to maintain attentive wakefulness and is characterized by duration,quality,timing,and efficiency.25Sleep duration guidelines proposed for adults from 18 to 64 years is 7-9 h per night.26Fruit and vegetables supply dietary fiber,vitamins and minerals,phytochemicals,and antiinflammatory agents.27Consumption of 400 g or more of fruit and vegetables per day,excluding starchy vegetables,is associated with protective effects against cardiovascular disease,some cancers,28depression,29and total mortality.20An inverse association between fruit and vegetable intake and mortality has been reported,with benefits observed in up to 7 daily portions.30Sufficient PA is defined as the achievement of 150 min/week or more of moderate-to-vigorous PA(MVPA),or 75 min/week or more of vigorous PA,or an accumulative equivalent combination of both,with added health benefits of 300 or more total MVPA minutes per week.31

Adequate sleep,healthy dietary behaviors,and sufficient PA also play an important role in strengthening the immune system and its antiviral defenses.32,33Lack of sleep,poor dietary habits,and physical inactivity are all independently associated with immunocompromising effects,32,34,35which impair host defenses against viral infection and may lead to individuals being at higher risk of more severe and complicated outcomes than those which are non-immunocompromised.36A lack of sleep,37dietary characteristics such as consuming a Western diet,38and insufficient PA are each associated with obesity,39which is suggested to be a profound risk factor for adverse health outcomes from COVID-19.40

Avoidance of health behaviors during a pandemic outbreak may lead to immunocompromise,increased susceptibility to viral propagation and elevated risk of severe symptoms.36,41Behavioral countermeasures for individuals are vital determinants to health resilience amongst exposure to unprecedented environmental events such as the COVID-19 pandemic.5Thus,evidence-driven interventions targeting the promotion of behaviors that enable individuals to protect themselves physically and psychologically during a pandemic are of public health importance.5,42No previous studies have examined change in health behaviors in airline pilots before and after a pandemic event like COVID-19,nor have any studies evaluated the effectiveness of a controlled lifestyle-based health intervention during such times.The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a 3-component healthy eating,sleeping,and PA program in airline pilots during COVID-19 lockdown in New Zealand.

2.Methods

2.1.Design

A between-group,parallel controlled study with pre-and post-test was performed to evaluate the effectiveness of a 17-week,3-component lifestyle intervention for enhancing health behaviors during a national COVID-19 pandemic response in New Zealand.

During the 17-week intervention period,the first 5 weeks preceded the New Zealand government’s enforcement of a 4-tier response system to COVID-19.1Thereafter,5 weeks were at alert Level 4(March 25 to April 27,2020),where all non-essential workers were instructed to stay home,and safe recreational activity was permitted only in the local area whilst maintaining social distancing of 2 m or more.Subsequently,2.5 weeks were at alert Level 3(April 27 to May 14,2020),where some businesses could reopen;however,people were instructed to work from home unless that was not possible.Finally,2 weeks were at alert Level 2(May 14 to June 8,2020),where gatherings of up to 100 people were allowed and sport and recreation activities were also allowed.On June 8,New Zealand returned to alert Level 1,43where within-community restrictions were removed yet international border restrictions remained.Around the globe in the weeks following the World Health Organization’s characterization of COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11,2020,the airline industry experienced a decrease of approximately 60%-80% in capacity at major carriers.9Consequently,pilots experienced limited flying duties during the time when the intervention was conducted(Table 1).Pre-test occurred between February 14 and March 9,2020,and post-test was conducted between June 8 and June 19,2020.At pre-and post-test,participants completed an electronic survey measuring the following outcome variables:self-report PA levels,dietary behaviors,quality and quantity of sleep,and subjective health.

2.2.Participants

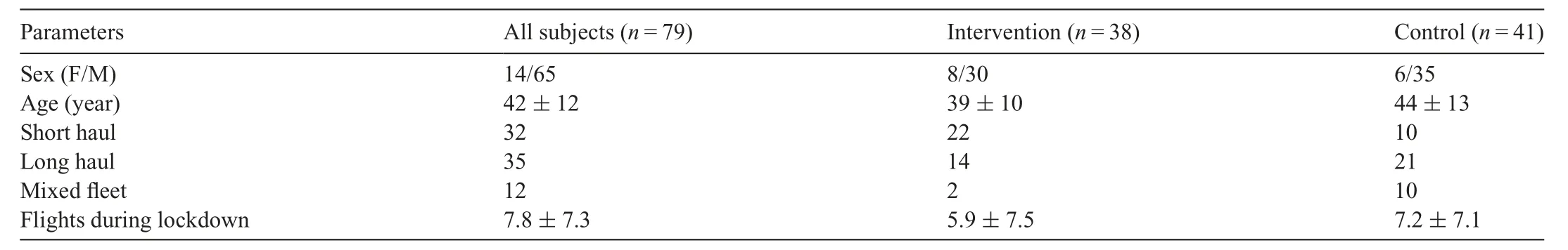

The study population consisted of commercial pilots from a large international airline.Seventy-nine pilots(aged=42±12 years,mean±SD;65 males,14 females)participated in the study(Table 1).Participants were from a combination of short haul,long haul,and mixed fleet rosters(n=32,35,and 12,respectively).Inclusion criteria were pilots who had a valid commercial flying license and worked on a full-time basis.Control group participants consisted of volunteers who were pilots recruited at the time they completed their routine aviation medical examinations at the airline medical unit during the pre-test period(between February 14 and March 9,2020).The intervention group volunteered to participate in the lifestyle intervention via self-selection.All volunteers participating in the study had responded to an invitation delivered to all pilots within the company via internal organization communication channels.In the control group,mixed-fleet pilots had the most flights,followed by long haul and short haul pilots(10±9 flights,7±7 flights,and 6±5 flights,respectively).In the intervention group,mixed-fleet pilots had the most flights,followed by short haul and long haul pilots(14±1 flights,9±9 flights,and 6±4 flights,respectively).All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study and were made aware that they could withdraw from the study at any time should they wished to do so.In order to support anonymity and dataset blinding during data analysis,participants were provided with a unique identification code on their informed consent form and were instructed to input it into their written survey instead of their name.This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Waikato in New Zealand(reference number 2020#07).

Table 1Baseline demographic characteristics of participants(mean±SD or n).

2.3.Intervention group

Participants who registered their interest in participating in the intervention and agreed to attend a face-to-face consultation session at the airline medical unit were included in the intervention group.The intervention group received an initial one-on-one 60-min consultation session with an experienced health coach,followed by provision of an individualized health program,weekly educational content emails during the intervention and a mid-intervention phone call.The health advice provided was evidence based and derived from experts in the areas of PA,nutrition,and chronobiology.

Personalized goal setting was carried out for each participant in the intervention group,with relevant outcome,performance,and process goals44discussed pertaining to each of the 3 intervention components:(1)dietary behaviors,(2)PA,and(3)sleep habits.Moreover,individual perceived barriers to health change were assessed with methods outlined elsewhere45and were factored into the individualized program.

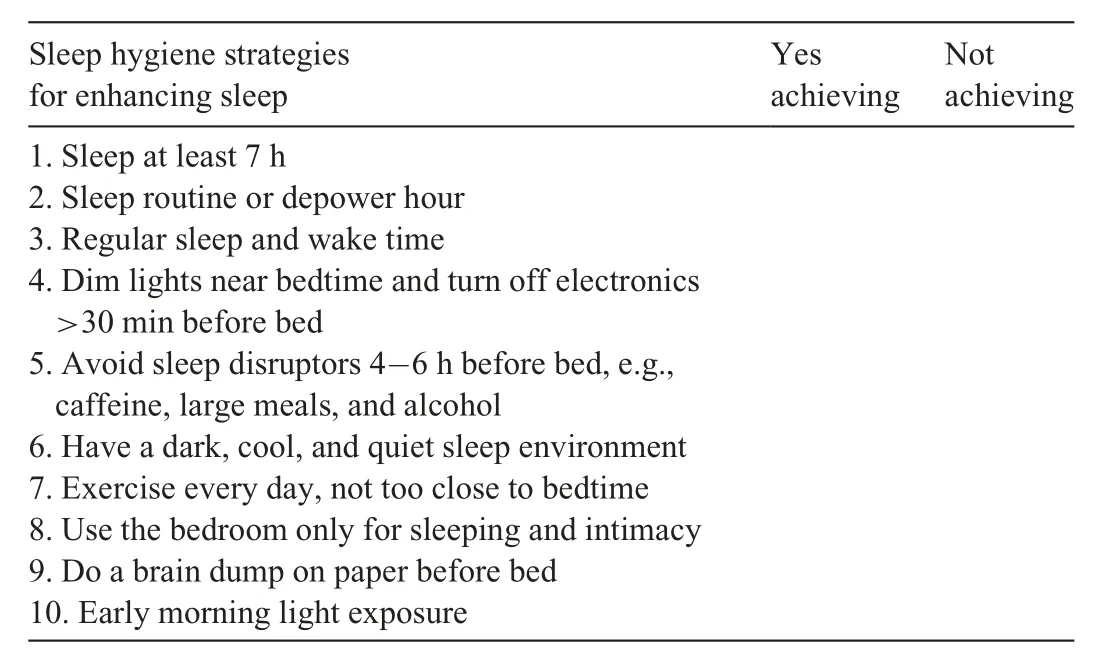

Sleep hygiene as an educational strategy has demonstrated improvements in self-report sleep quality in blue collar employees.46Stimulus control as a behavior technique has demonstrated positive outcomes on sleep parameters in insomniacs.47An evidence-based sleep health checklist was developed for utilization in this study(Appendix).The items in the checklist consisted of standard recommendations derived from previous sleep hygiene and stimulus control studies.48,49Application of the items in the sleep health checklist involved collaborative identification of the strategies that participants were achieving at baseline.Pilots completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index(PSQI)prior to attending their consultation.During the face-to-face consultation,the health coach discussed suboptimal PSQI component scores with the participant and identified individual sleep priorities.Thereafter,participants collaboratively set personalized sleep practice goals with support from the health coach.Personalized collaborative goal setting was implemented as a behavioral technique to support development of sleep habits that support restorative sleep.44

PA prescription was individualized based on participant perceived barriers and facilitators to exercise;45application of the frequency,intensity,time,and type principles;50and progression to attainment of sufficient MVPA to meet guidelines31in congruence with individual capabilities.The frequency and time of PA sessions were tailored to participant time availability.Intensity was tailored based on participant exercise experience,physical health,and goal orientation.51The type of PA was determined by the individual’s modality preferences for cardiovascular(such as walking,running,or cycling)and strengthening(e.g.,resistance equipment and/or bodyweight exercises)PA.The PA progression self-monitoring was indicated,and participants were advised to implement small,progressive changes in PA during the intervention(such as increased session duration,more repetitions,greater exercise intensity or more weekly bouts).52Healthy eating principles were emphasized through individualized advice and educational materials focused on adding color to the diet via consumption of fruit and vegetables;27choosing nutrient-dense foods;53limiting processed foods;enhancing whole-food consumption;54and reducing white carbohydrates,refined carbohydrates,and added sugar(e.g.,energy-dense food).55Relative to participant baseline behaviors,collaborative individualized process behavior goals were established,for example,adding color to meals and replacing high glycemic index foods with low glycemic index options.The prescribed dose of fruit was 2 or more servings per day,and the prescribed dose of vegetables was 3 or more servings per day.A mid-intervention(during Week 8±1)followup phone call lasting approximately 10 min consisted of a semistructured interview emphasizing discussion of progress and compliance pertaining to individualized sleep,PA,and dietary goals established during the pre-test consultation.Advice was provided when necessary and was consistent with the advice given at pre-test.Phone calls were used because they have been shown to support adherence to health interventions.56Congruent with evidence-based methods previously outlined,weekly emails were sent consisting of educational blog posts on varying topics related to sleep health,PA,nutrition,and support for a healthy immune system.Content was derived from health authorities via publicly available information from the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.During the COVID-19 lockdown,content was tailored to pandemic conditions,including strategies for PA at home,healthy recipes,and immune system health information.

2.4.Control group

The participants in the control group were blind to the intervention and received no intervention or instruction regarding health behaviors between pre-and post-test.Control group pilots were invited to voluntarily complete an electronic survey,and those who completed it during the previously defined pre-test period prior to COVID-19 lockdown were sent an invitation via email to voluntarily complete the survey again during the post-test period in order to provide insight into the effects of COVID-19 lockdown on their health behaviors.

2.5.Instruments

The PSQI was utilized to evaluate subjective sleep quality,and scores were obtained before the start of the study at the pre-test and were compared to scores obtained at the post-test stage.The PSQI is a self-rated,19-item questionnaire designed to measure sleep quality and disturbances over a 1-month retrospective period.57Sleep quality component scores are derived for subjective sleep quality,sleep latency,sleep duration,habitual sleep efficiency,sleep disturbances,use of sleeping medications,and daytime dysfunction,and collectively produce a global sleep score.57Lower scores denote a healthier sleep quality and range from 0(no difficulty)to 21(severe sleep difficulties).57The PSQI has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and validity and has been implemented in many population groups.57,58The outcome measurements were the change in global score between each group at post-test.

PA levels were assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire(IPAQ)Short Form,a validated selfreport measurement tool for MVPA that has been widely utilized in large cohort studies,including New Zealand population surveys.59The IPAQ Short Form estimates PA achievement by quantifying weekly walking,as well as moderate and vigorous PA duration and frequency.Responses were used to compare participants’PA levels with the health guidelines of 150 min of moderate PA or 75 min of vigorous PA per week,or an equivalent combination of MVPA per week.31IPAQ Short Form outcome measures derived were(a)total weekly minutes of moderate+vigorous PA in bouts of 10 min or more,excluding walking(IPAQ-MVPA),and(b)total weekly minutes of walking in bouts of 10 min or more(IPAQ-walk).Responses were capped at 3 h per day and 21 h per week,as recommended by the IPAQ guidelines.60Fruit and vegetable intake were measured using 2 questions with acceptable validity and reliability derived from the New Zealand Health Survey.59The questions asked participants to report,on average,over the last week,how many servings of fruit and vegetables they ate per day.Responses to these questions were combined to determine total daily fruit and vegetable intake.

Subjective self-report physical and mental health was determined using the Short Form 12v2(SF-12v2),a short version of the SF-36,which reduces the burden on participants and has demonstrated a high correlation with SF-36 physical and mental component summary scale scores.61The 12-item survey produces a physical component summary(PCS-12)scale and a mental component summary(MCS-12)scale,both of which have shown good test-retest reliability and convergent validity in detecting changes in mental and physical health over time in adults.62Scoring of the SF-12v2 was carried out in accordance with standard summary scoring methods.61The summary scores are on a scale of 0-100,with clinical significance change scores suggested to be 5-10 points.63

2.6.Statistical analyses

For all statistical analyses,raw data were extracted from the Qualtrics online survey software(Qualtrics,Provo,UT,USA),entered into an Excel spreadsheet(Microsoft,Seattle,WA,USA)and then imported into the SPSS(Version 26;IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA).Listwise deletion was applied for individual datasets with missing values or participants who did not complete post-test.Stem and leaf plots were inspected to ascertain whether there were any outliers in the data for each variable.A Shapiro-Wilk’s test(p>0.05)and its histograms,Q-Q plots and box plots were inspected for normality of data distribution for all variables.Levene’s test was used to test homogeneity of variance.Time-related effects within and between groups on pre-test and post-test were assessed usingttests and repeated measures mixed-design analysis of variance.Age,sex,and number of flights were included as covariates in the analysis of variance.Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’sdin order to quantify between-group effects from pre-test to post-test.Effect size thresholds were set at greater than 1.2,greater than 0.6,greater than 0.2,and less than 0.2,which were classified as large,moderate,small,and trivial,respecitvely.64Theαlevel was set at apvalue of less than 0.05.

3.Results

The demographic and baseline health characteristics between the intervention and control groups are given in Table 1.The attrition rates were 16% and 30% for the intervention and control group,respectively.Intervention group attrition was influenced by employment layoffs,whereas control group attrition was due to non-response to the online invitation to voluntarily complete the survey at the post-test period.In order to measure compliance,average sleep hours,exercise sessions per week,and daily fruit and vegetable consumption was collected at the time of the mid-intervention phone call.In the intervention group,35 participants(92%)were achieving 7.0 h or more of sleep per night and 3(8%)were achieving 6.9 h or less per night.For fruit and vegetable servings per day,36 participants(95%)were eating 5 or more servings of fruit and vegetables per day,whereas 2(5%)were eating 2-4 servings per day.For MVPA,33 participants(87%)were completing 150 min or more of MVPA per week and 5(13%)were completing 149 min or less of MVPA per week.

At baseline,the control group achieved significantly(p<0.05)more sleep per night(36 min),a lower global PSQI score(-1.9)(denoting better health),higher consumption of daily fruit and vegetables(1.2 servings),a greater amount of weekly walking(94 min),and higher SF-12v2 physical and mental component scores(8.4 and 6.7,respectively).At baseline,the control group exhibited an MVPA of 171±78 min per week,surpassing the MVPA recommended in the health guidelines of 150 min or more per week,31whereas the intervention group exhibited 116±51 min per week of MVPA,which is beneath the health guidelines threshold.However,the between-group difference in MVPA was not statistically significant(p≥0.05).

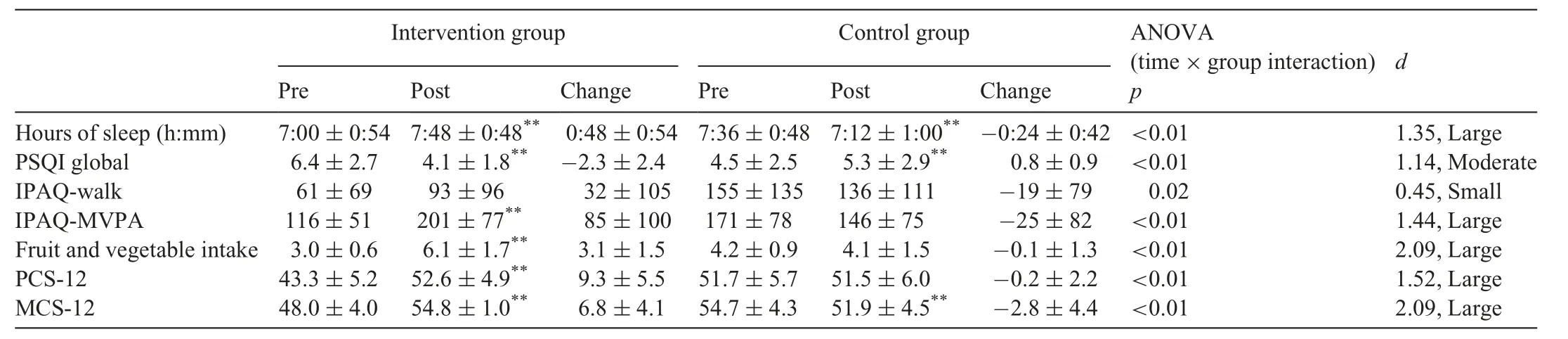

Group changes from pre-test to post-test are presented in Table 2.Significant main effects for time×group were found for IPAQ-walk(p=0.02)and for all other outcome measures(p<0.01),which is associated with small to large effect size differences between groups.The within-group analysis revealed that the intervention elicited significant improvements(p<0.01)in all health metrics at post-test and IPAQ-walk(p=0.02).The control group reported a significantly higher PSQI score(p<0.01),decreased hours of sleep and MCS-12 score(p<0.01),yet no significant change was reported in other health metrics.

Table 2Changes in health behaviors from baseline to post-test at 17 weeks(mean±SD).

4.Discussion

To our knowledge,this study is the first controlled experiment that has explored the effects of a lifestyle intervention on health outcomes among pilots during a national pandemic lockdown.This study aimed to improve health-related behaviors and promote positive change in subjective health of pilots through personalized advice on healthy eating,sleep hygiene,and PA.For most outcome measures,the controlled trial demonstrated significant improvements in the intervention group compared to the control group.These results are important in order for researchers and health care professionals to provide insight into potential health and quality-of-life perturbations resulting from COVID-19 that may have potential implications to flight safety.Furthermore,given the dearth of published data pertaining to health behavior interventions during a pandemic and the limited availability of preventive lifestyle-based interventions for pilots,our findings provide novel contributions to this field.

The average PSQI score for the intervention group decreased(-2.3),compared to a significant increase for the control group(0.8).These results support previous studies that used non-pilot populations,which have reported PSQI score decreases of-1.5 to-1.8 following a sleep hygiene education intervention46,65and-2.5 after a PA and sleep education intervention based on a mobile health app.66An app-based intervention to reduce fatigue in a pilot population reported a smaller effect on PSQI score(-0.59)after a 6-month intervention that focused on advice regarding daylight exposure and sleep duration.None of these studies were conducted under global pandemic conditions.A potential confounding factor to sleep quality and quantity improvements during COVID-19 due to social isolation and lockdown constraints has been proposed,67where more time at home and flexible sleep-wake schedules may promote enhancements in sleep.Furthermore,sleep disruption is an inherent risk for pilots,and they are likely to have better sleep quality and quantity when not at work.

Curiously,in our study the control group significantly increased its PSQI score.Similar findings have been reported elsewhere in a general-population-based study in Australia(n=1491),which reported that 40.1%of the participants indicated a negative change in sleep quantity during lockdown.8In another study,sleep quantity improved while sleep quality was degraded in Austrian adults(n=435).68In that study,an increase in subject burden and decreased physical and mental well-being were also observed.Cognitive states of elevated distress and emotional disturbances have been associated with unhealthy dietary patterns and poor diet quality and may impair health behavior motivation.5Researchers have advocated for implementation of strategies to mitigate the effects of lockdown on sleep quality,including obtaining sufficient PA,exposure to natural daylight,68and well-balanced meals rich in vitamins and minerals.5Our study findings support these messages in that we observed significant improvements in PCS-12 and MCS-12 scores among the intervention group compared to the control group,after implementation of a 3-component healthy sleep,eating,and PA intervention during an unprecedented global pandemic.

The average MVPA and fruit and vegetable consumption significantly increased in our intervention group,compared to no significant change in the control group.The intervention group increased MVPA from 116 min to 201 min at post-test,which crossed the MVPA guideline threshold of 150 min or more per week.31Conversely,the control group decreased MVPA from 171 min to 146 min per week at post-test,decreasing to below the guideline threshold.Both the control and intervention groups did not achieve the recommendation of 5 or more servings per day for fruit and vegetable intake at baseline.69The intervention group elevated its intake per day,achieving the guideline threshold at post-test.Our study findings suggest that the 3-component intervention supported achievement of PA and fruit and vegetable guideline thresholds and significantly improved PCS-12 and MCS-12 scores in the intervention group.Furthermore,the intervention appeared to mitigate decay in both SF-12v2 summary scales,which were observed in the control group.

Research exploring the relationships among COVID-19,PA and dietary behaviors have yielded mixed outcomes.Within an Italian population(n=3533)during COVID-19 lockdown,similar proportions of the participants stated that they ate less or had better diets(35.8%and 37.4%,respectively)in regard to intake of fruit,vegetables,nuts,and legumes.7Furthermore,their PA behaviors did not significantly change;however,a greater amount of exercise was completed at home.7In a study with Australians participants,48.9% expressed a negative change in PA during lockdown and also reported that negative changes in PA and sleep were associated with expression of higher anxiety,depression and stress levels.8In a Canadian sample(n=1098),those who engaged in more outdoor PA time during lockdown had lower anxiety levels than those who did not.70The COVID-19 lockdown in New Zealand at Levels 3,4 presented barriers for engaging in PA,such as social distancing,travel restrictions and inaccessibility to parks,gyms,and other recreational facilities,which may have promoted sedentary behavior and contributed to the decline in PA observed in the control group.4,17Other studies found that life stressors,including job uncertainty,9anxiety and psychological stress,2financial loss and disconnection with community and nature may have impacted health behaviors during this time.17In contrast,the reduced time at work has been suggested as a potential facilitative factor in enhancing health behaviors during lockdown,67because this naturally alleviates one of the most commonly expressed barriers to engagement in PA:a lack of time.

A limited number of studies have investigated the efficacy of interventions targeting healthy dietary and PA behaviors among pilots.A study of an app-based,6-month intervention using a pilot population reported significant improvements in their weekly moderate and strenuous activity(0.21 days and 0.19 days per week,respectively),as well as a reduction in their snacking behavior(-0.88 servings per duty).71Consultations with pilots on their diet and physical exercise behaviors yielded a positive change in their blood lipids and body mass index.12Our findings pertaining to MVPA,fruit and vegetable intake,PSQI and SF-12v2 among pilots provide promising preliminary outcomes regarding the effects of a 3-component intervention and warrant further investigation with objective measures of outcomes.

The differential recruitment strategies and limited exclusion criteria for the intervention and control groups are limitations that may have contributed to the significant differences observed at baseline for sleep quantity and PSQI score,IPAQ-walk,MVPA,fruit and vegetable consumption,and SF-12v2 subjective health scores,with superior results in favor of the control group.Thus,it is recommended that future research studies have more robust randomization assignment conditions for participant allocation to groups in order to increase the probability of capturing the true population average and enhance the generalizability of findings.Future research should also increase the sample size,given the apparent variances in health behaviors amongst the pilot population,which in itself warrants further investigation in order to characterize these variances.

Future research with pilot populations that compare singleto multiple-behavior interventions would provide valuable insight into the magnitude of the effects when these differing intervention approaches are used.Given the bidirectional relationship between sleep,nutrition,and PA and some evidence to suggest multiple-component interventions may elicit stronger participation and adherence,72we suggest future research examine more time-efficient and scalable strategies for implementation of a 3-component sleep,nutrition,and PA program.For feasibility reasons,self-report methods were utilized in this study,and the limitations of this approach have been discussed elsewhere.73To enhance outcome measure validity and reliability,it would be preferrable to use objective measurement methods such as actigraphy to monitor sleep and PA and photo logging of dietary behaviors to quantify health behavior metrics.Comparisons of our study to related studies are limited because most other studies were conducted under normal societal conditions while ours was conducted under pandemic conditions.

5.Conclusion

Behavioral countermeasures for individuals are vital determinants of health resilience during exposure to unprecedented environmental events such as the COVID-19 pandemic.5The attainment of sleep,fruit and vegetable intake,and PA guidelines is associated with increased physical and mental health,enhanced immune defenses,and a reduction in the risk of obesity.Evidence-based interventions targeting the promotion of these behaviors will enable individuals to protect themselves physically and psychologically during a pandemic,and therefore are of immense public health importance.The 3-component healthy sleep,eating,and PA intervention implemented in this study elicited significant improvements in sleep quality and quantity,fruit and vegetable intake,and MVPA and suggests that achieving these 3 guideline thresholds promotes mental and physical health and improves quality of life among pilots during a global pandemic.Our study of this intervention provides preliminary evidence that a low-intensity,multibehavior intervention may be efficacious during a pandemic and that similar outcomes may be transferrable to other populations.However,more robust recruitment methods are required to confirm our findings and increase their generalizability.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the pilots for participating in this study.

Authors’contributions

DW and NG participated in conceptualization of the study,data collection and contributed to the design of the study,data analysis,interpretation of the results,and manuscript writing;MD and BJ contributed to the design of the study,data analysis,interpretation of the results,and manuscript writing.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Appendix

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年3期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年3期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- A critical review of national physical activity policies relating to children and young people in England

- The evidence for the impact of policy on physical activity outcomes within the school setting:A systematic review

- State laws governing school physical education in relation to attendance and physical activity among students in the USA:A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Handgrip strength and health outcomes:Umbrella review of systematic reviews with meta-analyses of observational studies

- Is device-measured vigorous physical activity associated with health-related outcomes in children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Conceptual physical education:A course for the future Charles B.Corbin