A practical approach to pediatric liver transplantation in hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma

Ana M. Calinescu, Geraldine Héry, Jean de Ville de Goyet, Sophie Branchereau,#

1Division of Pediatric Surgery, University Center of Pediatric Surgery of Western Switzerland, Geneva University Hospitals,Geneva 1205, Switzerland.

2Pediatric Surgery Unit, Bicêtre Hospital, Université Paris-Saclay, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre 94270, France.

3Department for the Treatment and Study of Pediatric Abdominal Diseases and Abdominal Transplantation, IRCCS ISMETT(Mediterranean Institute for Transplantation and Advanced Specialized Therapies), Palermo 90127, Italy.

#Authors contributed equally.

Abstract Progressively, as chemotherapy has become more effective, more children with liver malignancies are amenable to liver transplantation, and indications have expanded from a limited range of cases (mostly hepatoblastoma) to a range of other unresectable malignant liver tumors; as a result, more children with hepatocellular carcinoma are also now proposed to transplantation, even and often outside the Milan criteria, for a cure. Recent series have highlighted that patient and graft survivals after transplantation for hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma have improved in the last decade. Although consensus has not yet been reached about transplantation as a possible cure for other tumor types than hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplantation,generally speaking, has become an important pillar in the management of pediatric liver malignancies. Remaining limitations and inquiries relate to patient selection (in term of selection criteria considering the risk of recurrence),the role and usefulness of chemotherapy after transplantation, or the best immunosuppression strategy to both protect renal function and improve outcome. Although some prospective studies are on the way regarding these aspects, more studies are needed to explore this rapidly changing aspect of care.

Keywords: Pediatric liver transplantation, hepatoblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Despite initial concerns about the risks of exposing oncological patients to immunosuppression, many series have confirmed that the outcome can be excellent even though these children are exposed to immunosuppression after total liver resection and liver transplantation (LT). As a result, LT has expanded as a possible cure and its role has become increasingly important in the management of pediatric liver malignancies. Overall, pediatric liver malignancies account for a tenth of all pediatric LT performed in the United States[1]; in Europe, 6% of all pediatric liver transplantations are performed for an oncological indication within the European Liver Transplant Registry[2]. By far, the most frequent pediatric liver malignancies proposed to LT are hepatoblastoma (HBL) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[3]. Although the place of LT is growing in the pediatric liver oncology setting, determinants of long-term survival are not very clear yet[4].

Unresectable HBL and HCC have as the only curable alternative total hepatectomy and orthotopic LT; it is a conclusion that was readily available in the early 1990s, with the advent of the first LT for unresectable pediatric liver malignancies[5]. The first study providing results for survival was SIOPEL 1[6]: it highlighted the importance of proposing LT as a primary strategy and avoiding using it as a last option or as a rescue of previous (failed) surgical attempts; while the former strategy provided excellent results, the latter was associated with poorer prognosis.

Tumor biological behavior has been shown to be not only an important parameter for patient selection but also an essential predictor of the outcome after LT[7]. Although 60%-80% of the patients presenting with HBL are unresectable at presentation and diagnosis[8,9], most respond so well to cisplatin and doxorubicin neoadjuvant chemotherapy that they become “resectable”[3](up to 85% of the initially “unresectable” tumors ending resected). Recent series have evidenced that in fact only 20% of the newly diagnosed patients with HBL eventually will need a LT[10-13]; for these patients, total hepatectomy and LT is the only option and possible cure, with standard/extreme resection less likely to be curative. More interestingly, even in these unresectable cases proposed to LT, it was suggested in 2002[7]and confirmed later that good responders to chemotherapy [as judged by dropping levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and reduction of tumor mass] have a better outcome after LT - this is common sense and can be used as a selection criterion.

HCC in children is rare and has a different biological behavior compared to HBL. In children, it also has a different physiopathology and behavior compared to that in adults, who present HCC mostly on cirrhotic liver, while in children HCC is usually a primary tumor on healthy liver. HCC in children is often unresectable at diagnosis (80%)[14]; however, multimodal treatment (i.e., chemotherapy and transarterial chemoembolization) has limited effect on HCC, with only 50% of HCC patients proposed for resection[15],and up to 25% will eventually need a LT[15,16].

THE ROLE OF LIVER TRANSPLANTATION IN HEPATOBLASTOMA

Indications and contraindications in liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma

Indications

Based on SIOPEL (International Childhood Liver Tumour Strategy Group), indications for LT in HBL patients include:(1) Multifocal PRETEXT IV tumors are the typical indication for LT, as by definition all liver sectors are invaded by the tumor or at least by one tumor node. In these cases, the concept of radical resection imposes total hepatectomy; the latter strategy is based on the fact that, although a tumor node (or metastasis) can clear on imaging, viable microscopic tumor residues may persist at the very site that seems “cleared” on imaging. In the latter situation, the only adequate strategy is to radically resect all liver segments that were positive for nodes at diagnosis - although they may be negative on POSTTEXT staging. Controversy persists about the former strategy, with some groups advocating the “pulmonary metastasis” approach, where the clearance of metastatic nodes after chemotherapy allows a “wait and see” policy - allowing to consider liver replacement and transplantation, as metastasis clearance is then considered “absence of active extrahepatic disease”[17-23]. In that context, proceeding with partial resection instead of total hepatectomy for PRETEXT IV HBL (and leaving in place liver segments that were positive at diagnosis but cleared during chemotherapy) made sense to a few teams in the last decade. Initial reports were rare and anecdotical (2 cases by Baertschigeret al.[18]in 2010 and 5 cases by Lautzet al.[20]in 2011); in the latter series, the only patient who died had partial hepatectomy in the absence of history of metastasis, and one emergency transplant was lifesaving for a child with ischemia after resection. Two other, larger series were reported recently (12 and 21 cases, respectively) (de Freitas Paganotiet al.[19]in 2019 and Fahyet al.[21]in 2020). In the de Freitas Paganoti series, 5/12 had partial hepatectomy (only 1/5 had an extensive hepatectomy), which was followed by a 31.0% recurrence within three years[19]. In the Fahy series, although the outcome is, generally speaking, satisfactory, the cohort description is insufficient to come to a precise conclusion about the children with a PRETEXT IV condition[21]. In a recent paper, Uchidaet al.[24]reported a series of 24 HBL (22 POSTTEXT II or III and 2 POSTTEXT IV) who were proposed for resection (N= 12) or LT (N= 12) on the basis of a local algorithm based on pre- and peri-operative imaging. Overall, recurrent disease was observed in 2/12 cases after LT and 5/12 cases after resection (2/5 received rescue LT successively), while overall survival was 100% after LT and 91.7% after resection (recurrence-free survival being 91.7% and 58.3%,respectively).

Initial reports of non-transplant approach for PRETEXT IV cases triggered comments from many expert surgeons, worldwide, highlighting the risk of encouraging fewer expert teams to proceed with inappropriate surgical strategies when extreme surgery is associated with higher technical complications rates[23]. This has been followed by a series of reports in recent years where there is evidence that:

- PRETEXT IV stage is one of, or “the”, most negative prognostic factor for HBL patients[22,25,26].

- Radical resection and efficient chemotherapy are both essential for the cure of HBL, which supports the role of LT for complete disease removal in the case of PRETEXT IV at diagnosis, in order to avoid local recurrence[17,25-27].

- Liver transplantation played an important complementary role in managing HBL children and contributed to the recent increase of survival[24,28,29].

- Although transplantation might be viewed as an “over-treatment” in some cases, it is associated with excellent outcome, while late rescue transplantation (for local recurrence of disease) is the worst scenario,with very poor outcome[6].

The debate is still active[17,24,30,31], and only dedicated structured prospective studies will be able to answer this delicate question, which cannot be answered at the level of single centers. This might be addressed in the future by the upcoming international protocol “Pediatric Hepatic International Tumour Trial” (PHITT)[32].

(2) Large solitary PRETEXT IV tumor, unless downstaged after chemotherapy[33].

(3) Large central PRETEXT II and III tumors invading bilaterally the confluence at the porta hepatis or all three hepatic veins[6,34-38].

(4) Local (intra-hepatic) recurrence of HBL after liver resection[3].

(5) Complications of “extreme resections”, i.e., early liver failure (due to small-for-size, ischemic damage, or other intraoperative complications) or late complications[6].

The two last categories are defined as “rescue” or “salvage” transplantation, accounting for 15%-40% of all LT performed for HBL in a recent review[17]. In the latter situations, LT is associated with poor outcome(30% survival with most deaths due to recurrence[39]), yet LT remains an option in well selected cases[3,38].

ContraindicationsPersistence of macroscopic metastasis (visible on imaging) after chemotherapy and not amenable to surgical excision remains the only absolute contraindication for LT[39]. Although there is no consensus, some consider that response to chemotherapy is a requisite for transplantation, with progression of disease under chemotherapy being a contraindication to LT[3,8].

In all indications, although the presence of metastases at diagnosis is not a contraindication, the control under chemotherapy (with disappearance at imaging) of the metastasis is mandatory before LT. In cases with some residues at the location of previous metastases, the strategy may consist in surgical resection of these metastases before LT.

The clearance of lung metastasis prior to LT is of utmost importance: a wedge resection is performed the most often; in the case of more than four nodules in the same lobe, lobectomy might be considered as a surgical option[17]. Median sternotomy with manual palpation of both lobes might be a valuable option in bilateral lung residual metastasis[40-42]. The alternative is sequential surgeries in the case of bilateral involvement[17].

Surgery tips and tricks

In cases with tumors very close to, encircling or infiltrating, the retro hepatic vena cava, en bloc resection of liver with the vena cava is recommended, with some teams deliberately using this approach for all cases.Venous reconstruction is performed by using donor iliac vein allograft in the case of LT with deceased donation[39]. As the latter reconstruction is challenging in the context of living donor LT (lack of donor vein allograft), this situation (that was once considered a contraindication for LT from living related donors[43]) is nowadays managed by using the jugular vein of the recipient or from the same donor[3,44,45]. Other options of using vessels from the same living donor have been proposed (recanalized umbilical vein, external jugular vein, or superficial femoral venous graft) and others have proposed cryopreserved vessels from unrelated donors[45,46]. Of note, in the case of large tumors compressing the inferior vena cava with pre-LT sufficient venous return via collaterals to the azygous system, caval vein reconstruction has not been systematically needed[47].

The impact of an early inflow (arterial and portal) exclusion with temporary portocaval shunt was studied for the effect on recurrence: firstly, early inflow interruption might prevent tumor dissemination through the hepatic veins because of surgical manipulations as well as diminish blood losses minimizing the requirements for transfusions.

Secondly, temporary portocaval shunting could maintain renal perfusion pressure, which might contribute to the preservation of the postoperative renal function as well as diminish the splanchnic congestion of HBL patients that do not have portosystemic collaterals and thus increase the likelihood of an optimal healing of the Roux en Y loop[48]. In this series investigating the early inflow exclusion, a recurrence free survival rate of 88.9% at one year with preservation of residual renal function was obtained[48].

Finally, an extensive en bloc hepatectomy technique was described in a series with excision of retrocaval retroperitoneal tissue, en bloc lymphadenectomy with peri-choledochal and hepatic hilum nodules along the common hepatic artery, and frozen section from all resection margins; the overall survival in this sevenpatient series was 100% without recurrence seven years after LT[49].

Timing of liver transplantation and metastasectomy for hepatoblastoma

The timing of LT should not be delayed after four weeks after the last course of chemotherapy given the impact on survival; if an expeditious access to deceased donation is not possible, a living related donation should be considered[33,39]. A possible option for those who are waiting for a liver from a deceased donor is to plan a new course of chemotherapy if they are not transplanted during the first window of four weeks; these cases are of course not offered a graft during chemotherapy, but this strategy allows a second window of transplantability of one month, after the new course. The latter strategy imposes of course that not all chemotherapy courses are done before the registration of the patient on the list for transplant, but it has been very effective in avoiding exposing the patient to prolonged periods with no chemotherapy and allowing a LT within these time windows.

Children’s Oncology Group recommendations in 2016 stated that evaluation for surgery should be done after two cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy[50]; nevertheless, some tumors continue to regress between Cycles 3 and 4. Thus, after four rounds of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 45% of the tumors are down staged,vs. only 30% after two cycles; thus, if chemotherapy is well tolerated, it should be continued to allow more patients to undergo successful resections[51].

Clearance for metastasis should be achieved earlier in the chemotherapy course, with SIOPEL 4 recommendations to achieve metastatic control after three induction cycles of chemotherapy[17].

Complications after liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma

Morbidity after LT in HBL might arise from three origins: (1) chemotherapy toxicity, namely nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, and sepsis with early discontinuation of adjuvant treatment; (2) surgical morbidity; and (3) immunosupression[50].

At transplantation, the renal function of patients with HBL is reduced because of the toxicity of neoadjuvant chemotherapy; although it can be expected, it has been clearly emphasized that the renal function further deteriorates after LT[52,53]. As the cause for further decline of renal function after LT is directly caused by the sequential and combined toxic effects of chemotherapy and immunosuppression, the strategy has been to use either lower anticalcineurin levels for these patients (compared to standard LT in other indications)[33,53]or low-dose anticalcineurin treatment in association with other immunosuppressives (i.e., mycophenolate mofetil)[54]or early conversion to mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors[55].Overall, morbidity associated to LT might be as high as 67%[56], with infection being the first cause. This risk may be increased in patients who are exposed to both immunosuppression and chemotherapy; in a monocentric report, infection was identified as the most common morbidity and reached a level of 36%(cholangitis, bacteremia, central line infections, abdominal collections, and pneumonia)[57]. Vascular complications are the second most frequent cause of problems after LT and seem to be higher in patients transplanted for malignancies. Hepatic artery thrombosis is reported to be as high as 28%[4,11,58]. Although some groups do not mention a higher thrombosis risk after LT for HBL patients[59], this might be because these patients do not have liver dysfunction, portal hypertension, or hyper splenism and their coagulation profile is normal at LT, with a possible increased procoagulant activity due to cisplatin. This might justify the systematic use of antithrombotic and/or anticoagulant strategy after LT for HBL[11].

Biliary complications might occur in up to 40% of the cases, as in other indications for LT[60,61]. In a 19-patient series, one patient (5%) developed a bile duct stricture treated with percutaneous transhepatic cholangioplasty and one bile leak (5%) was treated by percutaneous drainage[50]. Farajet al.[59]described an incidence of 8% biliary complications: two bile leaks, one needing a percutaneous drainage and the other laparotomy and drainage. The Japanese national cohort of living donor LT for HBL showed overall 47.2%surgical complications: 21.7% biliary complications for the hepaticojejunostomy subgroup and 31.3% for the duct-to-duct anastomosis subgroup[62].

Other complications such as small bowel obstruction[59]and chylous ascites resolving spontaneously[59]were described more rarely.

Rejection-free survival in HBL recipients with living related donor grafts was 91% compared to 58% in controls; it is thought that less immunosuppression is required after LT for hepatoblastoma as a result of diminished immunity after neoadjuvant chemotherapy[3,33,53,58]. The findings of rejection rates seem different in the case of deceased donation with 50% and 70% in two series with 8 and 10 patients, respectively[60,63]. A larger study confirmed the difference in rejection rates with 50% rejection in HBL patientsvs. 75% in a matched biliary atresia LT patient cohort[52]. Furthermore, decreased rejection rates persist many months after completion of chemotherapy, probably suggesting an immunomodulatory effect other than just immunosuppression[58]. Together with the altered renal function, the decreased rejection rates suggest a need for immunosuppression modulation after LT for HBL.

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease was reported in 10% of patients[60]. Nevertheless, none of them died in a United Network Organ Sharing (UNOS) database inquiry[64].

Retransplantation was reported to occur in 10% of the patients after LT for HBL, because of vascular thrombosis (60.6%), primary non-function (15.2%), and rejection (9.1%)[11,60].

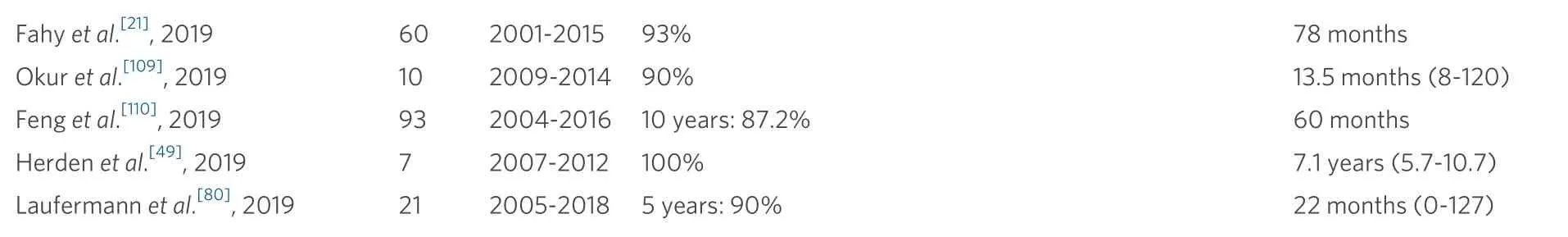

Survival after liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma

Historically, patients with advanced and metastatic HBL had a 5-year survival of 69%, as reported in 2006[65]. Almost 10 years later, improved chemotherapy and aggressive transplant listing upgraded 10-year patient survival to 84%[4,21]. A retrospective UNOS analysis identified an overall survival of 76% with a graft survival of 77%. The three-year overall patient and graft survival was of 85% starting with 2009[8]. These results are in line with the SIOPEL 3 and 4 trials that found a 75% overall survival for patients with unresectable HBL[22,66][Table 1].

Table 1. Overview of articles looking at survival after pediatric liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma

Fahy et al.[21], 2019 60 2001-2015 93% 78 months Okur et al.[109], 2019 10 2009-2014 90% 13.5 months (8-120)Feng et al.[110], 2019 93 2004-2016 10 years: 87.2% 60 months Herden et al.[49], 2019 7 2007-2012 100% 7.1 years (5.7-10.7)Laufermann et al.[80], 2019 21 2005-2018 5 years: 90% 22 months (0-127)

In an attempt to reduce the time between diagnosis and LT, an early referral practice was introduced in the late 2000s, with a parallel evaluation of resection and potential LT; the major success of this approach was to reduce the number of secondary LT[50].

Survival in the case of “rescue LT” seems worse at five years, at less than 30%[12,63]. Overall, a literature review identified a survival of 41% for rescue LT[67]. A Japanese study identified a 72% 5-year overall survival in a series of 11 “rescue LT” patients[68].

LT outcomes for HBL patients with synchronous lung metastasis eradicated before LT are excellent at one and five years, 93.3% ± 4.6% and 86.4% ± 6.3%, respectively[69]. Single pulmonary metastasis and patients with lesions visible only on CTvs. lesions visible on both CT and chest X-ray have a better outcome[35,70].

The need for chemotherapy after LT is a matter of debate: a review did not identify a statistically significant difference in survival rates with and without post-LT chemotherapy[6], nor did the Pediatric Liver Unresectable Tumour Observatory registry[71]. Some studies promote its use in the case of vascular invasion or large proportion of viable tumor in the explanted liver[72]. The survival rates seem improved even if statistical significance was not reached in the series inquiring into this issue[73].

Recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma

Tumor recurrence is the most frequent cause of death: up to 50% of the patients with tumor recurrence die,usually within two years after LT[21,59,65]; the longest interval between LT and recurrent HBL was 2.8 years in the Japanese national survey[62]. A review identified 14.6% of the relapse HBL patients after LT to be alive and disease free[68].

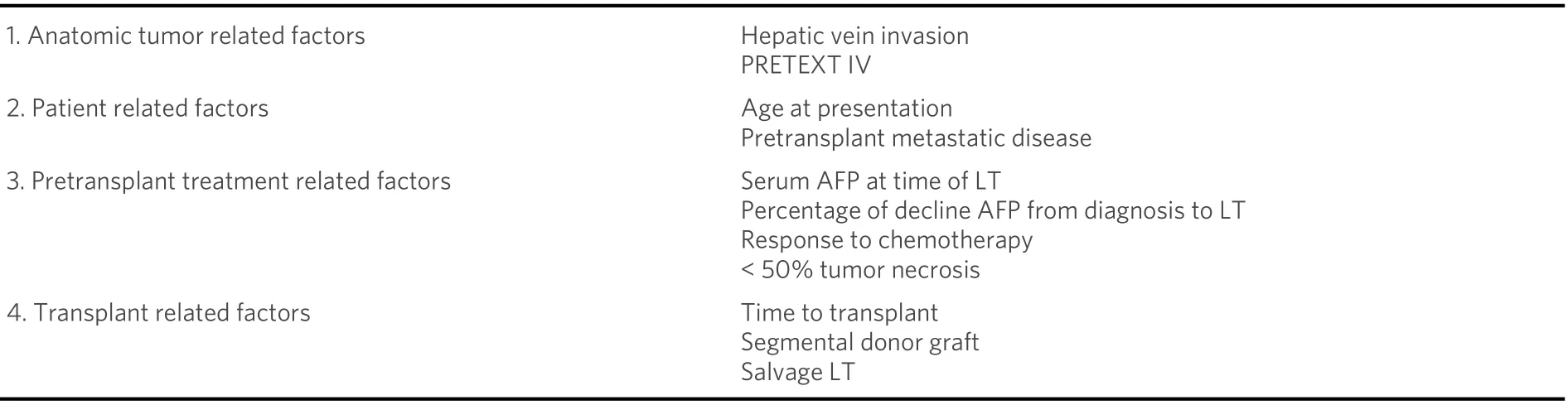

Recurrence after LT for HBL presents itself mainly as metastatic disease and is encountered in as high as 40% of the cases[11,60]. It is thought to correspond to a more aggressive type of tumor to which transplantation will not respond better than initial resection[73]. This seems to be supported by the findings of Khanet al.[74]: in their institutional review, none of the HBL patients had a complete tumor response. As a surrogate marker for recurrence, AFP levels after LT could be a valuable adjunct, with a series reporting a normalization of AFP values in the subgroup of patients without recurrence and staying increased or even further increasing in patients with recurrence[75][Table 2]. In cases with limited and regional relapse(typically a single node in the abdominal area), re-resection strategy may offer a cure (personal communication)[62].

The long-term survival of patients having a LT for HBL shows the following risk factors for tumor recurrence: PRETEXT IV, tumor rupture, higher time spent within the waiting list (15 daysvs. 31 days),older age (78 monthsvs. 48 months)[4], macroscopic vascular invasion, extrahepatic lesions at the time of LT, presence of viable tumor (tumor necrosis less than 50% and high preoperative AFP values), tumor shrinkage rate of ≤ 30%, and high AFP at diagnosis and LT[11,59,62,76,24].

Table 2. Risk factors associated with hepatoblastoma recurrence after pediatric liver transplantation

Previous lung metastases, initially considered as favoring recurrence, were recently proved not to be risk factors for tumor recurrence[77]. In the case of limited recurrence, especially if recurrence is at sites previously diagnosed and clearing under chemotherapy, an aggressive surgical approach and resection has been proposed; the latter outcome may be favorable as these recurrences are in fact local relapse rather than new secondaries associated to systemic relapse[62].

The 3-year recurrence free survival was reported to be 78% in a cohort of 15 patients with rescue LT[62].Later, an 11-patient Japanese series reported a recurrence rate of only 27% in this subgroup of rescue LT[68].

Segmental grafts (from cadaveric or living donors) versus cadaveric whole liver grafts seem also to make HBL recipients more prone to recurrence; whether this difference is due to the cava-sparing hepatectomy technique is not clear yet[8,11].

Overall, longer waiting list time was found to be associated with higher recurrence risk, a rather intuitive finding[4].

Post-transplantation chemotherapy seems to decrease the tumor recurrence[6,73,78]. It is thus recommended,although it might be difficult to practically implement because of complications after transplantation[73].There is actually no uniform policy for the post-LT chemotherapeutic regimen and its clinical relevance is still debated[68].

In recurrent HBL after LT, the increasing AFP levels pretransplant despite continued neoadjuvant chemotherapy led to the conclusion that LT should be performed before the tumor acquires chemoresistance and thus before the decrease in AFP levels reaches a plateau[79]. Patients with higher pre-LT AFP also exhibited a higher risk for non-curable relapse than patients benefiting from LT at lower AFP[80].

THE ROLE OF LIVER TRANSPLANTATION IN HEPATOCELLULAR CARCINOMA

Indications and contraindications in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma

Indications

The first study inquiring the role of LT as primary surgical treatment for HCC without extrahepatic involvement was from Czaudernaet al.[81]in the early 2000s. They highlighted that the results of the conventional resective approach in cases with resectable tumors were far less favorable than those who benefited from LT for unresectable masses. This opened a window of opportunity for proposing LT as a curative strategy for children with unresectable HCC. Although there is still no consensus about the criteria for proposing LT to manage HCC in children, the results of Czaudernaet al.[81]emphasize that HCC in children is different from that in adults. Hence, an opposite strategy to that of HCC in adults could be followed: while HCC are selected for LT in adults with smaller tumors, in term of mass and/or number (the Milan criteria)[82], there are no well-defined pediatric criteria to contraindicate the HCC candidate for LT[82]as follows:

(1) Unlike adults, HCC occurs in children mainly in the absence of concomitant cirrhosis[12], and this is one reason for a different selection strategy. The Milan criteria, developed for adults with cirrhotic liver disease,have been adopted by some centers (one tumor of 5 cm or less or no more than three nodules of 3 cm or less) in an effort to improve survival rates[3]. The more liberal criteria of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) are partially adopted by some other centers[72]. More extensive criteria, “up to seven”(number of lesions and diameter), show a minimal decrease in survival rate, from 71% to 65%[83].

(2) The practice guidelines of the American Association for Transplantation and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition recommend an individualized indication for LT for each patient[84]. Basically, LT is recommended for HCC patients in the case of no extrahepatic tumor or gross vascular invasion on radiological imaging, irrespective of the number or size of the lesions[84].

(3) In Japan, the Japanese Organ Transplantation Act proposed the rule of 5-5-500: tumor size ≤ 5 cm diameter, tumor number ≤ 5, and AFP level ≤ 500 ng/mL for living donor LT for HCC in adults[85].Modifications of this rule were adopted (Kyoto criteria, Tokyo 5-5 rule, and Kyushu University) with larger inclusion of patients but lower survival and higher recurrence rates[85].

Of note, none of these are validated in pediatric HCC[86]. A general consensus is to offer LT for unresectable HCC patients and no extrahepatic disease[87], while LT should be considered even for patients with HCC PRETEXT I or II in selected cases[88].

Contraindications

Because HCC in children is different to that in adults and the Milan criteria do not strictly apply, proposing LT in pediatric HCC remains a delicate choice and strategy: patients should be evaluated individually within multidisciplinary teams including oncologists, hepatologists, pediatric surgeons, and pediatric liver transplant surgeons[89]. As evidenced for HBL, tumor behavior during chemotherapy and downsizing may be important elements to consider for indicating LT as a curative option.

Major vascular venous invasion (especially the extrahepatic invasion of vena cava and portal vein trunk) is a contraindication for transplantation in HCC due to poor long-term prognosis - unless neoadjuvant chemotherapy achieves an evident down staging[90]. As for HBL, the presence of extrahepatic tumor is a contraindication for transplantion[14]. Fibrolamellar variant of HCC constitutes the third contraindication[91].

Survival after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma

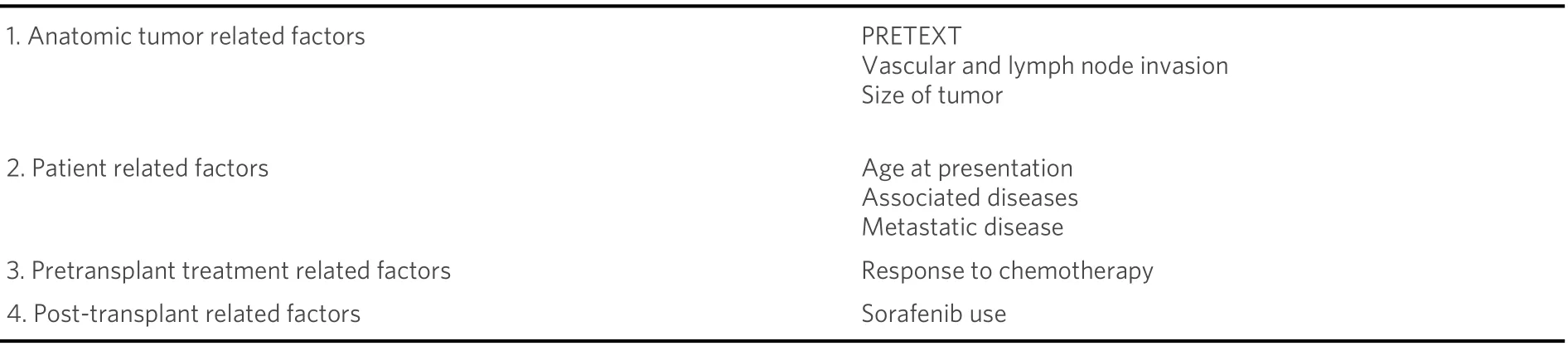

HCC seems to behave differently in children than in adults as LT for lesions outside the Milan and UCSF criteria still lead to excellent long-term survival[4]. A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database review identified an 89% 4-year overall survival with 27.6% of the patient most likely outside and 34.5%definitely outside the Milan criteria[92]. A retrospective UNOS database analysis identified an overall patient and graft survival of 63% with 3-year overall patient and graft survival of 84% starting with 2009[8][Table 3].

Poor prognostic factors for HCC are as follows: metastasis, large tumor size, lymph node extension, and macroscopic vascular invasion[1,3][Table 4].

Table 3. Overview of articles looking at survival after pediatric liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma

Table 4. Risk factors associated with hepatocellular carcinoma outcome after pediatric liver transplantation

Younger age was found as a prognostic factor for a better survival in LT after HCC[93].

Survival seems worse for HCC newly diagnosed in a healthy liver than HCC diagnosed during surveillance for a chronic disease or incidentally discovered in the explants of LT for another disease[3,93,94].

The role of chemotherapy in pediatric HCC is still debated: although it responds to chemotherapy more than adult HCC, pediatric HCC for which chemotherapy was administrated failed to show an improved survival in both adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings[89,92]. Data from the PHITT that administers neoadjuvant chemotherapy to patients with unresectable HCC at diagnosis will eventually answer this question[89].Survival rates were higher for patients responding to preoperative chemotherapy[81].

The use of sorafenib has shown better survival rates in the adult population, demonstrating an improvement in median overall survival (10.7 monthsvs. 7.9 months)[95]; in children, few data have been published in this respect[15].

Overall survival was not different in subgroups according to 5 cm cut off, vascular invasion, and the Milan criteria[89]. No differences in survival have been found when comparing living donors to deceased donors[96].

When studying treatment choice, a 21-patient series comparing outcomes for resection and chemotherapyvs. LT in pediatric HCC reveals a superior survival (72%vs. 40%) in the LT subgroup, pointing out the need for the early evaluation of transplantability of pediatric HCC patients in the treatment course[88].

Recurrences after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma

During surgery for HCC, operative manipulation, increased intraoperative blood loss, and blood transfusions are thought to be potential mechanisms for tumor recurrence[97,98].

The risk factors identified for recurrence of HCC are as follows: tumor stage, vascular invasion, and lymph node involvement. In the long term, older age and metastatic disease were additionally identified[1,4,90].

Few series describe the outcome of HCC patients with macrovascular invasion undergoing LT; a 5-year recurrence free survival of 89% is reported in a 10-patient series[99].

Unlike adults, the risk for recurrence is not higher if patients do not meet the Milan criteria[8]. Given higher recurrence rates of HCC after surgical resection than after LT, it is hypothesized that LT should be liberalized even for resectable tumors[8].

Of note, no recurrence was identified in the patients for whom HCC was incidentally discovered in the liver explant[1].

The recurrences and impact on survival of deceased versus living LT has been studied in the adult literature but very few data are available within the pediatric literature[100].

Whether corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors increase the likelihood of tumor recurrence after LT for HCC is not clear yet; it is the reason for some centers to privilege the use of sirolimus, as it has been shown to inhibit the growth of a wide variety of tumors[3]. An adult study did not show an improved long-term recurrence free survival beyond five years, but it increased the overall survival and the recurrence-free survival in the first three to five years after LT[101].

ONGOING AREAS OF RESEARCH

Pediatric LT has a growing place in the management of unresectable HBL and HCC. There are still unanswered questions concerning the role of post-LT chemotherapy for HBL, immunosuppression modulation, and the correlation of the AFP levels after LT with survival. Besides an obvious need for validated LT criteria for pediatric HCC patients, the impact of chemotherapy and waiting time for LT are still to be studied.

CONCLUSION

Pediatric LT in the oncological setting has evolved during the last two decades into an effective procedure for a selected subgroup of patients. Indications are quite clear in HBL but still need validation in pediatric HCC patients. This review focuses on indications and limitations in the LT treatment of unresectable pediatric HBL and HCC. The ongoing PHITT trial will probably provide evidence-based guidelines for the LT management of pediatric patients with unresectable HBL and HCC.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study, performed data analysis and interpretation, finally approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work: Calinescu AM, Héry G, Branchereau S, de Ville de Goyet J

Performed the draft: Calinescu AM, de Ville de Goyet J

Critical revision of the intellectual content: de Ville de Goyet J, Branchereau S, Héry G

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2021.

- Hepatoma Research的其它文章

- 3D Organoid modelling of hepatoblast-like and mesenchymal-like hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines

- Effect of mesenchymal stem cell in liver regeneration and clinical applications

- BOOST: a phase 3 triaI of sorafenib vs. best supportive care in first Iine treatment of hepatoceIIuIar carcinoma in patients with deteriorated Iiver function

- Prognostic factors associated with survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolisation: an Australian multicenter cohort study

- AUTHOR INSTRUCTIONS