Detection of adrenal mass during an educational point-of-care ultrasound in the emergency department

Kay Negishi, Jorge Short Apellaniz, Daniel Ratanski, Sarah E. Frasure, Andrew S. Liteplo, Hamid Shokoohi

1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston 02115, USA

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington 20037, USA

Dear editor,

Incidental adrenal mass is a common radiological finding that is mostly detected in abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans.[1]Though pheochromocytomas are a relatively rare chromaffin cell tumor, they are a“cannot miss” diagnosis, as they can be fatal.[2]With the current widespread use of emergency physicianperformed point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), the abdominal ultrasound examination may be used in cases of acute abdominal pathology such as intraperitoneal free fluid, kidney stones, an ectopic pregnancy, gallstones,and an abdominal aortic aneurysm.[3,4]An assessment of the adrenal gland is generally not the primary focus of an abdominal POCUS evaluation. When performing standard POCUS in the emergency department (ED),clinicians may encounter adrenal masses.[5]We present a case in which an incidental f inding of an adrenal mass revealed a pheochromocytoma in a patient who presented to the ED with newly decompensated congestive heart failure and persistent hypertension.

CASE

A 79-year-old man with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, daily alcohol consumption,and coronary artery disease, presented to the ED with a recent diagnosis of depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) reported on an outpatient transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). The patient described intermittent lower extremity edema for one year and gradually worsening dyspnea on exertion for two weeks. He denied chest pain, headaches, palpitations,f lushing, or diaphoresis. During his most recent primary care physician visit, he was noted to have an elevated N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP).This laboratory result prompted an outpatient TTE,which revealed severely depressed LVEF of 12%. The patient was immediately sent to the ED for further evaluation and treatment.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure 137/96 mmHg (1 mmHg=0.133 kPa), heart rate 115 beats per minute, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, temperature 36.2 °C, and pulse oximetry 98% on room air. His cardiac examination was notable only for tachycardia; he had no gallops, murmurs, or rubs. His pulmonary examination was normal, without crackles, wheezing, or increased work of breathing. He had moderate symmetric pitting edema of his legs. An electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated a normal sinus rhythm with left bundle branch block and anterolateral Q-waves. The patient was admitted to the cardiology service and boarded in the ED while awaiting a telemetry bed in the hospital. When boarding in the ED, he was approached by a team of emergency medicine ultrasound trainees, including medical students, residents, and an ultrasound fellow, who asked if they could perform an educational sonographic cardiac, thoracic, and abdominal ultrasound examination. The patient consented and an educational POCUS was subsequently performed.

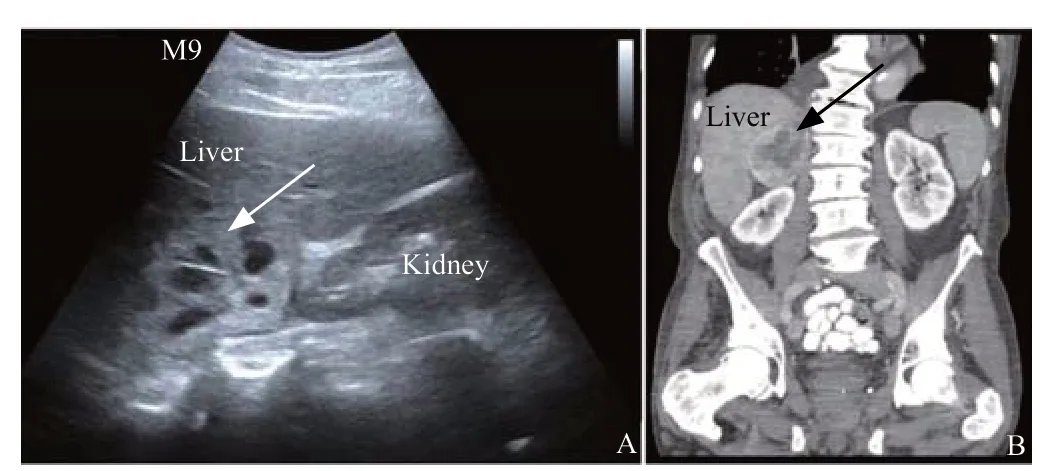

The ultrasound reaffirmed the presence of severely depressed ejection fraction. There was no B-lines on the thoracic ultrasound. While assessing for the presence of a pleural effusion on his right side, a heterogenous mass was visualized in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen (Figure 1A). This incidental finding was communicated to the inpatient team and an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was subsequently obtained. A large heterogeneously enhancing mass in the right adrenal gland, concerning for a pheochromocytoma or an adrenocortical carcinoma, was identified on CT imaging (Figure 1B).

Further testing revealed increased urine and serum metanephrines (25,344 mcg/24 hours and 34 nmol/L, respectively), consistent with a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. The patient subsequently underwent a total right adrenalectomy and pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of pheochromocytoma (Figure 2). He had left heart catheterization, which revealed clinically significant three-vessel disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention. He also received an implantable cardioverter defibrillator during his hospitalization. He was discharged in a stable condition from the hospital after five weeks. His diuretic and cardioprotective agents (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and beta blocker) were significantly decreased since his adrenalectomy.

DISCUSSION

In general, ultrasound scanning of adrenal glands is not a primary indication for POCUS, nor is it expressly taught as a part of the POCUS training curriculum for emergency physicians. If an emergency physician sonographer notices a mass along the upper pole of a kidney in the perirenal fat tissue, he/she should image the area of interest in both the longitudinal and anterior transverse planes, using a curvilinear transducer with a frequency of 2-5 MHz.[6]Anterior transverse scanning is a preferred method of scanning if a clinician is looking for small adrenal masses. After visualizing the suspected adrenal mass in two planes, the clinician should utilize color flow imaging to rule out a vascular structure.Normal adrenal gland tissue is usually hypoechoic; its echogenicity resembles that of the perirenal fat tissue.The identification of a mass of unclear etiology on POCUS should prompt the clinician to alert the primary medical team taking care of the patient in the ED in order to facilitate further imaging studies to help with proper diagnosis and treatment.

Figure 1. Images of point-of-care ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan. A: right upper quadrant ultrasound demonstrating a heterogeneous mass with multiple anechoic areas (arrow) above the upper pole of the right kidney, consistent with an adrenal heterogenous mass; B:abdominal CT scan in the coronal view conf irming a large and intensely heterogeneously enhancing mass (arrows) in the right adrenal gland.

Figure 2. Pathological examination results. A: gross pathology of right adrenal gland, which was surgically removed; B: its micropathology showing aggregates of cells with a mosaic-like pattern with salt and pepper nuclei and granular cytoplasm.

In this patient with severely depressed LVEF, the educational POCUS looking for right-sided pleural effusion revealed an adrenal mass. Further imaging,laboratory testing, and pathological findings were consistent with a diagnosis of pheochromocytoma. Prior to this admission, the patient had experienced labile hypertension, which required up-titration of multiple antihypertensive agents, and he had also developed decompensated heart failure. Considering his other comorbidities, the patient was initially presumed by physicians to have ischemic, hypertensive, and alcoholic cardiomyopathy. The incidental finding on POCUS,however, determined the true etiology of his symptoms.The clinician sonographers were able to identify the abnormal imaging on their educational scan because they were already familiar with the sonographic appearance of normal anatomy learned during their emergency ultrasound rotation in the ED. While incidental f indings can lead to both unnecessary and harmful intervention,the identif ication and work-up of the mass noted on our educational ultrasound offered diagnostic clarity and led to the proper treatment.

In academic EDs where educational POCUS is routinely performed, there is always potential for detection of incidental f indings unrelated to the indication for performing the scan but of clinical value for patient care. When patients undergo educational POCUS in the ED all f indings are relayed to the emergency physicians taking care of the patient to help determine if further imaging is needed. The patient is also made aware of the findings (which typically include asymptomatic gallstones, kidney stones, renal cysts, ovarian cysts, and small pericardial or pleural effusions of unclear etiology)and a note is made in his/her medical record. If the patient is admitted to the hospital the inpatient medical team is made aware of any education ultrasound f indings.If the patient is discharged from the ED this information is added to the discharge paperwork to ensure timely follow-up.

In ED cases with incidental ultrasound findings,despite various factors that may affect follow-up testing/imaging adherence, one area where EDs have room for improvement is in the clarity of follow-up recommendations. Communicating the ultrasound results and follow-up plan with patients and their primary care physicians and formalizing a clear plan for further referral or testing should be included in ED protocols where educational POCUS is performed.

Certainly, in this case the abnormal sonographic finding was immediately noted during an educational scan and further imaging was expeditiously obtained by the patient’s medical team which revealed the patient’s true diagnosis.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Conf licts of interests:The authors declare that there is no conf lict of interest.

Contributors:KN wrote the main body of the article. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

World journal of emergency medicine2021年2期

World journal of emergency medicine2021年2期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- World Journal of Emergency Medicine

- Overlapping public health crises during the coronavirus disease pandemic

- Comparison of intraosseous access and central venous catheterization in Chinese adult emergency patients: A prospective, multicenter, and randomized study

- Empyema associated with vegetable foreign body aspiration

- A red herring: An unusual case of pneumothorax

- A case of a successful post-transcatheter aortic valve replacement His bundle pacing