PICTORIAL ELEMENTS VS. COMPOSITION? “READING” GESTURES IN COMEDY-RELATED VASE-PAINTINGS (4TH CENTURY BC)*

Elisabeth Günther

Classical Archaeology, University of Trier

(Ancient) images are sources in the eyes of many scholars, suitable for reconstructing historical events, daily life, and beliefs of the past, mostly by complementing visual and written sources. In this paper, I will draw attention to the fact that images (just like texts) are complex and polyvalent sign systems,always choosing a specific perspective on ancient life,1This idea was further stimulated and strengthened by the topic of the conference where the paper was presented: “Ad Fontes Ipsos Properandum! Law, Economy, and Society in Ancient Sources.Conference on the Occasion of the 35th Anniversary of the Foundation of the Institute for the History of Ancient Civilizations (IHAC) and the 60th Birthday of Professor Zhang Qiang” in Changchun,China. I would like to thank the organizers and participants for the fruitful discussions.and intentionally providing selected information to the viewer, using cognitiveframes.2This approach is based on E. Goffman’s Frame Analysis (Goffman 1974), cf. also Minsky 1980;Ziem 2014.Suchframes, built up and modified by experience and expectations, are the basic tools of the viewer by means of which to decode or “read”3This metaphor originates in linguistics but has become more popular in archaeological scholarship in the recent years, see, e.g., Steiner 2007; Stansbury-O’Donnell 2010.an image. Crucial for the process of perception and interpretation is a network of mentalframes. The individual elements of an image, e.g., its figures and objects, evoke certain or even differing meanings based on the viewers’ common knowledge. In this way,each viewer constructs a semantic network between the elements, and this serves as a basis by which to interpret the image. This can (but need not) fully correlate with the semantic network of the artist who applied his or her own knowledge,experience, and iconographic tradition to the artwork. The painter may even combine contradictory or incongruentframesto toy with the expectations of the viewer. This paper, however, focusses on theframesof the reception process.The viewer may not decipher allframesintended by the painter (due to his personal knowledge, e.g., of comedy plays and iconographic traditions), or may even add “readings” that were originally not intended.4If the viewers’ frameworks differ, this may cause ambiguities, see Günther 2021.In this sense, images inhere a certain potential to evokeframesand therefore narrations; this should be considered an important entity within the communication process between painters and viewers. Seen conversely, the “reading” of a single element always depends on the fullframenetwork available. This raises a further question:to what extent does the “reading” of an image, i.e., the activation of certain cognitiveframes, depend upon the choice of a certain element, and to what extent does a specific “reading” of the element depend on the composition as a whole?In turn, how does this influence the “reading” and perception process as a whole?

A small group of red-figured vases produced in southern Italy and Sicily during the 4th century BC provides a suitable sample by means of which to approach these questions.5Cf. esp. Trendall 1967a; Taplin 1993, 30–74; Green 2012.These vases display comedy-related scenes with actors interacting with one another, and, in some cases, they even integrate a wooden stage in the scene. One can easily identify the actors since they wear masks with a very distinct physiognomy, padding on their chest, stomach, and back,and an artificial phallus, all of which inverts notions of the ideal Greek body(kalokagathia); additionally, the actors cover their arms and legs with sleeves.6Webster 1948; 1953–1954; 1960. This costume closely resembles Attic terracotta figurines: Green 1994, 34–38. For the naturalism of the costume and its development, see id. 1997; for the masks,id. 2003. An overview is provided by Hughes 2006 and 2012, 166–191, but the author is primarily interested in reconstructing ancient acting styles, rather than iconography.Thus, the artificial character of the costume is clearly visible in the images,and the viewer is always aware of the fictionality of the respective scene.7Giuliani 2013 and 2018. For the metatheatrical effect of these vases, see below.The careful rendering of each detail within the paintings caused scholars to believe that the vases depict ancient stage performances.8For this “realism” approach, see Csapo 2010, 38–67; Green 1997.According to this approach, the customers of the painters’ workshops could identify the scene or the characters of a play,9Taplin 1993, 90.and this made such comedy-related vases an attractive product throughout the 4th century BC, particularly in and near not only the Greek colonies such as Metaponto, Taranto, Paestum (Poseidonia), and Syracuse, but also in Italian settlements.10These vessels were mainly (but not exclusively) found in tombs, both in Greek colonies and in Italian settlements of the 4th century BC. Thus, the vases bear witness to the interaction of Greek and Italian cultures, not as complementary or even separate groups, but as a fusion between different cultures creating something novel with respect to identity, depending on the region and time in which we find a flourishing comedy culture. The discussion of to what extent Greek (Attic) drama and/or Italian drama influenced the vase-paintings from southern Italy and Sicily began already in the 19th century (cf. Taplin 1993, 52–54). For the most recent points of view, see the papers in Bosher 2012,esp. Dearden 2012; Taplin 2012; Todisco 2012; and the papers in Csapo et al. 2014. For questions concerning acculturation and identity connected with comedy-related vases, see Schönheit 2016 and 2018. For Greek pottery in indigenous contexts, see Carpenter 2003 and 2009.Although comedy is obviously the primary cognitive frame for the viewer to “read” such a vase-painting, the painters composed the images very carefully and even included figures without costumes, i.e., figures that cannot have been part of a stage performance.11E.g., “paraiconography,” i.e., the parody of iconographic elements of “serious” vase-paintings(cf. Taplin 1993, 79–88). For the difference between images and stage performances, see also Green 2015, 45; Csapo 2010, 57–58.In addition, most vases do not display a play known to us today;12Except for a bell-krater in Würzburg with a scene of Aristophanes’ play Thesmophoriazousai:Würzburg, Martin von Wagner-Museum H 5697 (CVA Würzburg (4) pl. 4; Taplin 1987, 96–101;Csapo 1986; 2010, 52–58).this not only results from the fact that the literary evidence for comedies in the 4th century BC is extremely scarce, but also from the manner in which the painters composed the images: inscriptions and specific objects (props) that could identify a certain play are mostly missing.Instead, simple compositions with two figures, often understood as stock themes or “conversational pieces,”13Green 2012, 312. For the terminology of “conversational pieces,” cf. Franceschini 2018, 20–21.became popular, especially in Apulia after 360 BC.14For the development of comedy-related vases, see Green 2012; a re-examination of the workshops and their chronology will be published in my PhD-thesis “Komische Bilder. Bezugsrahmen und narratives Potenzial unteritalischer Komödienvasen” (“Comic Images. Cognitive frames and narrative potential of southern Italian comedy-related vases”): Günther forthcoming.This means that comedy-related vases are often misunderstood as factual depictions of historical stage performances,15For a critique of this approach, see Walsh 2009, 8; Dearden 2012, 282; Maffre 2000.while they rather use the cognitiveframesof masks, costumes, stages, and so forth to evoke an environment of theatrical action in which they implement, and provoke, narratives on their own.

To demonstrate how this exactly works, I will focus here on one group of pictorial elements, namely gestures. Gestures form the very starting point of a visual narration in combination with the body-language of the figures, their movements, and postures.16Stansbury-O’Donnell 1999, 21. On body-language in the Hellenistic period: Masséglia 2015.Knowing that they are part of an ongoing albeit unfinished movement “frozen” in the image,17For the problem of “frozen” gestures in ancient art, cf. Marshall 2006, 168.the human mind tries to complete the whole gesture, and the eye of the viewer starts to follow the gesture’s and the movement’s direction, respectively.18Id., 60–61. On non-comic examples, see Stansbury-O'Donnell 2014.

There is a long discussion in scholarship whether gestures in vase-paintings work like a vocabulary for decoding the interaction in an image, or whether they become only intelligible via the context of the scene in which the interaction takes place.19An overview of comedy-related gesture is provided by Hughes 2012, 146–165, 137, fig. 38, and Neiiendam 1992, 56–62. On the possible meaning of some gestures and their meaning for behavior and character: Green 2001; 2014; 2015. For southern Italian vase-painting, including some comedy-related vases, see Schulze 2000. For Roman Comedy, cf. Marshall 2006, 159–202. Regarding ancient gesture and body-language in general, see Sittl 1870/1970; Fehr 1979; Neumann 1965; Bremmer 1992; Graf 1992. For gestures on red-figured Attic vases in the 6th and 5th centuries BC, see McNiven 1989.Alan Hughes proposed specific meanings for some gestures in comedy-related vase-paintings, such as “stop,” “rebuke,” “admonitory,” “ward,”or “rejection,”20Hughes 2012, 137, fig. 38 with illustrations. Similar Neiiendam 1992, 56–62.while Kathrin Bogen, who analyzed greeting gestures on Attic vases, has shown that several different gestures can indicate greeting.21Bogen 1969, esp. 77.Other studies emphasized highly conventional gestures like the speaking gesture, which later became the sign for benediction, or the gesture ofaposkopein, i.e., lookingout while one hand protects the eyes from the sun, still common today.22Richter 2003; Jucker 1956.

While some gestures depicted in images do, indeed, seem to convey a specific meaning, others depend very much on the context of the interaction. Thus, it is worth analyzing the gestures and body-language of figures in comedy-related vase-paintings, and to discuss how much the “reading” of these pictorial elements depends on conventional signs, how much they are embedded in a network of elements and cognitiveframeswithin a composition, and how the relationship between elements and composition contributes to a visual narration that goes beyond the usual scope of stage performances.

How to interpret gestures in comedy-related vase-paintings

The first possible source for the painters regarding gestures on comedy-related vases is undoubtedly the comic stage. However, it is still under discussion to what extent the painters and their customers were familiar with such stage performances. While the (Attic) theater culture which spread widely throughout the Mediterranean in the 4th century BC was certainly present in the Greek colonies, it is unknown where, when, and how stage performances were delivered in the Italian settlements where many comedy-related and other red-figured vases were found.23For the spread of Greek theater culture in southern Italy, see the papers in Bosher 2012. For the theory of actor troupes having toured through this region, see Hughes 1996. For the technitai, an actors’ guild including actors who travelled to perform, see Le Guen 2001, the evidence, however, is from the 3rd century BC onwards: ibid., 6–14.Since most vases in indigenous settings were discovered in rich burials where the settlement was not too far from the Greek colonies or at least from places where red-figured vases were found in huge numbers (such as Ruvo, Bari, and Pisticci),24All available archaeological records of comedy-related vases are now compiled and analyzed in Günther forthcoming.this indicates that the arguably quite wealthy owners were at least to some degree familiar with Greek culture and also with stage performances.25Luca Giuliani proposed that the large Apulian volute-kraters that show tragic plots were presented(or rather “staged”) during the burial of the elite by a professional actor (Giuliani 1995, 155–158).This interesting suggestion, however, cannot be proven by the sources (critique by Dally 1997).Nonetheless, if the painters chose too specific gestures used only for comic (or tragic) performances they were at least risking that some customers might not have been able to decode them. The same accounts for another context where gestures played an important role: the rhetorical stage. Although Greek writers like Aristotle stress the importance of oratorical delivery,26Aristot. Rhet. 3.1.2 (trans. Freese 1926): “In the first place, following the natural order, we investigated that which first presented itself – what gives things themselves their persuasiveness; in the second place, their arrangement by style; and in the third place, delivery, which is of the greatest importance but has not yet been treated by anyone. In fact, it only made its appearance late in tragedy and rhapsody, for at first the poets themselves acted their tragedies. It is clear, therefore, that there is something of the sort in rhetoric as well as in poetry, and it has been dealt with by Glaucon of Teos among others.”any information about rhetorical gestures is lacking,27Though Aristotle acknowledges in his Rhetorics (3.1.2, see n. 26 above) the importance of delivery,he focusses on the orator’s voice and does not discuss gesture. The book of his pupil Theophrastus on delivery has unfortunately been lost, and thus we are informed on rhetorical gesture only by Roman authors, mainly Cicero and Quintilian. The gestures they report are so specific that they are not useful to gain a better understanding of the much earlier 4th century BC vase-paintings. In particular, Quintilian describes a sign language specific for a rhetor: Maier-Eichhorn 1989; Graf 1992; Dutsch 2013.and we must keep in mind that“delivery” included not only gesture, but also body-language and intonation.In addition, the orators in Athens always had to balance their body-language according to the virtue ofsōphrosynē, which becomes obvious in the 4th century BC statues of Sophocles and Aeschines, and the role they played in a verbal exchange between Demosthenes and Aeschines.28Aeschin. In Tim. 25; Demosth. 19(= De Falsa Leg.).251–252. Cf. Zanker 1995, 40–89. On sōphrosynē, see Bremmer 1992; sōphrosynē on comedy-related vases: Green 2001, 41–43.On the comic stage, on the contrary, expressive gestures, quick movements, and running were important,particularly for slave characters.29Csapo 1993 (on the servus currens, cf. also Quint. Inst. 11.112). Green has shown that the inversion of sōphrosynē plays an important role in the movement, body-language, and appearance of actors in comedy-related vase-paintings: Green 1997, esp. 133–134; 2001. Cf. also Hughes 2012, 152–153.A third context for gestures was daily life,and although the “vocabulary” of gestures might not have been exactly the same in the different regions of southern Italy and Sicily and may have differed between Greek colonies and indigenous settlements,30Gesture is highly culture-specific, cf. Graf 1992, 36–37; Marshall 2006, 168.they were probably more widespread than specific gestures connected with the theatrical or rhetorical stage. Furthermore, we can assume that quotidian gestures influenced gestures on stage, and vice versa.31Green argues for similar gesture conventions in performance, daily life, and in the paintings: “The painter is employing gestures well known in art to convey what is happening. We cannot guarantee that the actor on stage on the occasion the painter recalls made identical gestures, but in broad terms it seems likely. Gestures in art recall gestures in life, and if an actor in a Greek theater wanted to make his meaning clear, he would tend to use the same conventions.” (Green 2014, 107).Thus, all three contexts might have served as a source for the painters, and the actual choice would have necessarily differed between painters, workshops, and regions.32The influence of workshops and painters on the actual design of the pictorial elements is decisive but cannot be examined in this paper in detail (see Günther forthcoming). On the other hand, the depiction of actors follows similar iconographic conventions. Comedy-related vases are thus a starting point from which to study southern Italian and Sicilian vases across the boundaries of the different production regions (Apulia, Lucania, Campania, Paestum, Sicily) established by A. D.Trendall, which have become border lines within scholarship ever since. Especially in the second half of the 4th century BC, the mutual influences of Apulian, Campanian, and Sicilian workshops become clearly visible in the iconography of comedy-related vases, cf. Günther forthcoming.

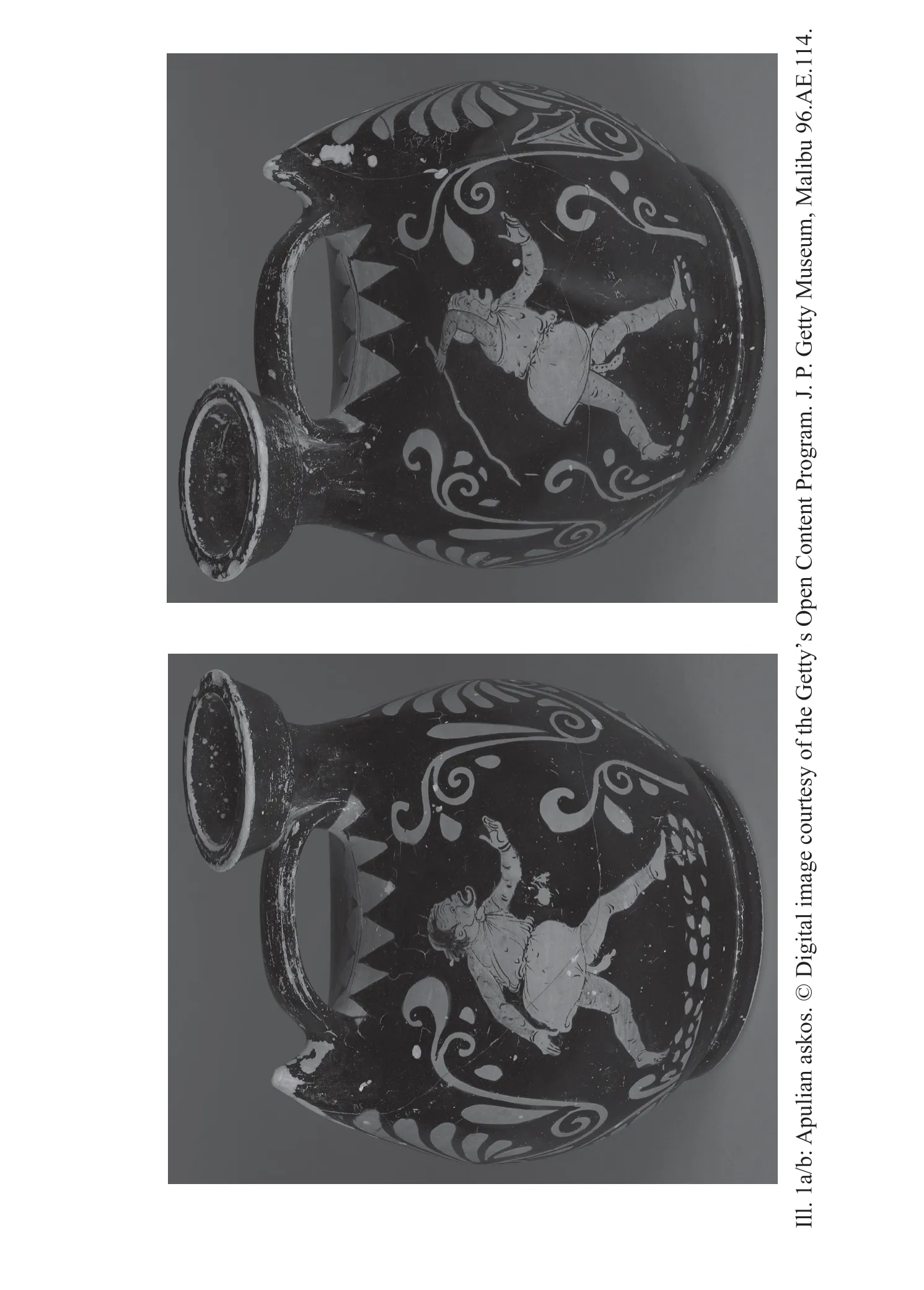

A second aspect is also important: A painter was not only compelled to choose which gesture a figure should use, but also had to decide which instant of the movement he should capture in the image, and he had to project his imagination of a three-dimensional figure into a two-dimensional scheme.33Cf. Franceschini 2018, 36–37; Catoni 2005.From the many solutions to this problem, the painter chose only one, and with this he transformed the stage character into a figure within an image that could evoke a set of cognitiveframesin the viewers’ minds and create a specific narrative.An askos in the Getty Museum Malibu,34Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 96.AE.114, height: 17cm; length: 16cm; Robinson 2004, pl. 27, 3;Green 2012, 321 and 338, no. 52; Trendall and Cambitoglou 1991, 74, no. 11/133b, pl. 12, 5–6; see:http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/29524 (30.04.2021).painted in Taranto, Apulia, between 360 and 340 BC (ill. 1a/b) provides a clear example of this transformation process. On one side, a comic actor is running to the right. He wears a comic mask, the comic costume with paddings, leggings, and a huge phallus; above the undergarment which represents the naked body of the figure,35On stage, only the hands and feet of the actors were visible; this undergarment represents the naked body of the stage character.he wears anexōmis, a simple dress which is fixed on the left shoulder only. Not only his widespread legs indicate that he is running fast, but his arms support the impression of movement. He stretches the left arm forward and turns the palm upward while slightly extending the thumb. The gesture and the movement of the figure guide the eyes of the viewer to the right, and, indeed, when the vessel is turned, a second, nearly identical figure may be found on the other side.Again, a comic actor runs to the right, his left arm outstretched with the very same gesture. His white hair implies an older age, and he swings a stick with his right arm above his head. This refers to a common motif in ancient comedy: the punishment of a slave, who is beaten by his master with a stick.36Cf. Webster 1948, 24–25. This motif appears three times among comedy-related vases, cf. a calyxkrater in Berlin (Berlin, Staatliche Museen und Antikensammlung F 3034, Green 2012, 111, 124,no. 28, pl. 14.1) and the famous Goose-play krater in New York (Metropolitan Museum 24.97.104,Marshall 2001). A master approaching his slave who seeks refuge on an altar is another typical motif;the master is usually depicted as an older man, and wears a himation and holds a staff, cf. a skyphos in Gela (MAR 643, Green 2012, 319–320 with fig. 14.17 and 338, no. 49) and cf. terracotta figurines depicting a slave sitting on an altar (e.g., Louvre CA 265, Webster and Green 1978 no. AT 110 a–e and 124, no. AT 111 a–i). On the depiction of slaves in comedy-related vases in general, see Green 1997, 171; Bosher 2013.For the punishment of slaves in literary sources, see Aristoph. Vesp. 448–452; Equ. 1–5; cf. Theophr.Char. 12.12 (trans. Diggle 2004): “He [the tactless man, E. G.] stands watching while a slave is being whipped and announces that a boy of his own once hanged himself after such a beating.” For the asylum-seeking slave, cf. Wrenhaven 2013, 133–135.The gestures not only connect both sides, but also bear a certainaffordance37On the affordances of images, see the conference proceedings of “Mehrdeutigkeiten. Rahmentheorien und Affordanzkonzepte in den archäologischen Bildwissenschaften” (“Ambiguities.Frames and affordances in ancient visual culture studies”); see: https://www.topoi.org/event/46051(30.04.2021), now published as Günther and Fabricius 2021; on the approach and theoretical background in particular: Günther 2021.for the viewer to turn the vessel again and again, watching the figures chasing each other in an endless circle.38For similar effects, cf. Stansbury-O’Donnell 2014. To one of the reviewers of this article I owe an interesting thought: Were this askos to have been used by a slave to pour liquid in his master’s vessel with his right hand, then the sequence of the story “master chases slave” would have started with the master. For the (real) master, watching his slave pouring wine into his drinking vessel, the sequence would have started with the slave, chasing the master, which might be understood as a funny inversion of the story. In addition, that only after a turn of the slave/vessel the full story became intelligible to the master, might have caused a funny “surprise” effect. Since the vessel was probably found in a tomb – according to its perfectly preserved state – it is impossible to prove whether this joke was indeed intended by the vase painter, and the thoughts presented here must remain pure speculation.Additionally, this gesture causes another comic effect: The painter has chosen exactly the same projection into the two-dimensional images for both figures. With this social “manipulation,” he puts master und slave on an equal footing: there is no difference anymore between them, except for the stick representing the (currently lost) power relation. The funny and provocative message may have been as follows: the master is not better than his slave; he is superior in terms of his legal status, but not in terms of physis and morality.

Categorizing gestures on comedy-related vases

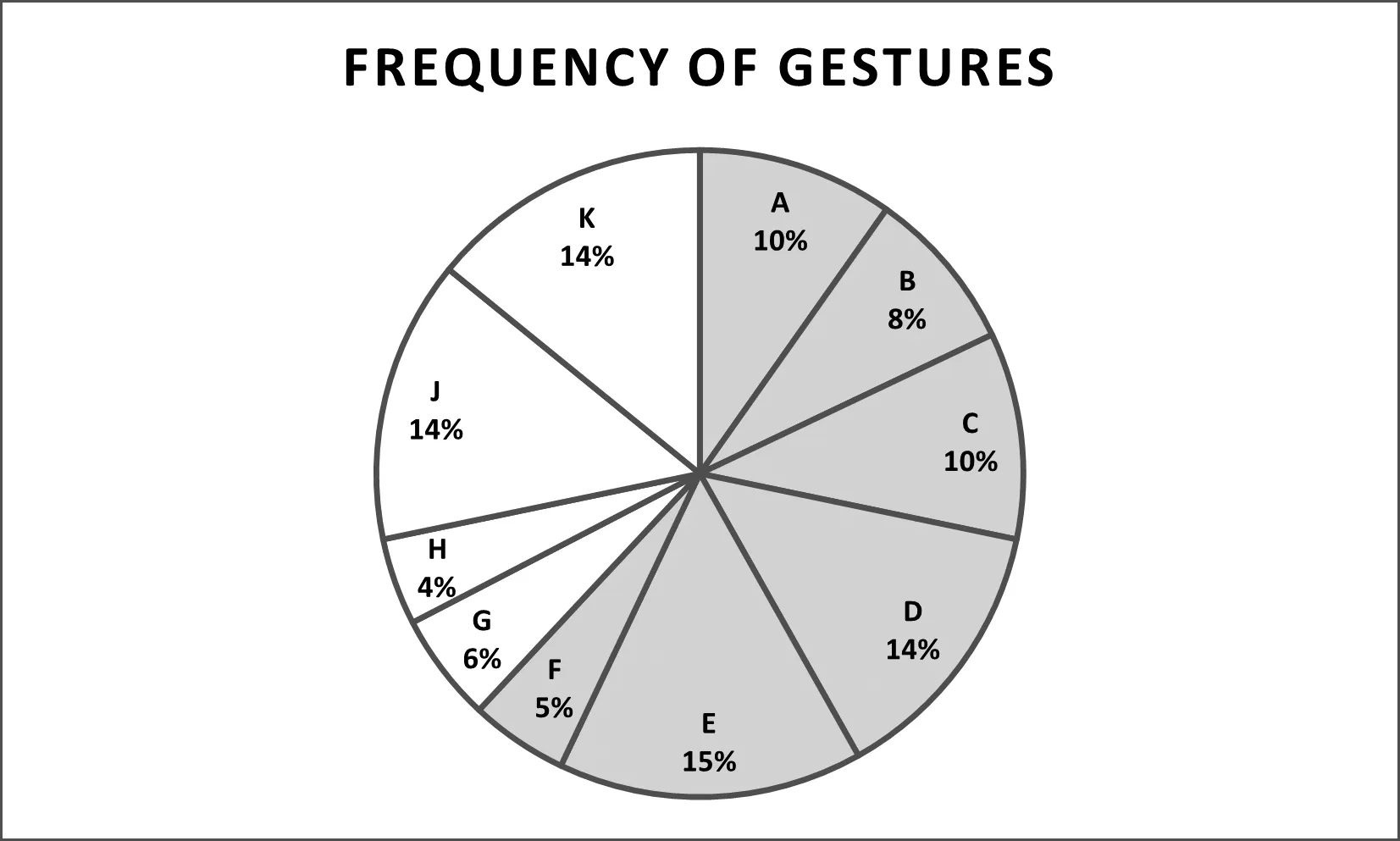

After some initial exemplary considerations regarding the limits and potential of the visual medium to employ gestures, it is time to examine the spectrum of gestures in comedy-related vase-paintings, and their possible meaning and functions. To gain an overview, the gestures can be categorized according to the position of arms and hands. We can distinguish at least ten different gestures(fig. 1). The most frequent gestures are simple movements based on outstretched arms and hands (A–D). The palm can be turned away from the body, e.g.,towards another figure (A: 10%), or it can be turned toward the viewer (B: 8%),downwards (C: 10%) or upwards, like in ill. 1a/b (D: 14%); the latter is also suitable to indicate a greeting.39E.g., Bari, MAN 8014, Green 2012, 308–309 with fig. 14.9 and 335, no. 32.These gestures can involve one arm or both;the use of both arms may intensify the communication,40E.g., on an Apulian bell-krater by the McDaniel painter: Harvard, Harvard Art Museum 2007.104.4, TL 33186, Green 2012, 300 with fig. 14.5, 302–303 and 334, no. 27.or may result from the figure’s movement (as in ill. 1a/b).

Fig. 1: Frequency of gestures in comedy-related vase-paintings (n = 184 gestures by 165 figures).41The data refer to the number of gestures shown on the vases. On 225 vases, I counted 420 figures whose hands were not damaged. Among these, 332 figures wear a comic costume, 82 do not wear a comic costume, and in case of 6 figures, it is not clear whether they wear a costume or are meant to be a parodistic depiction of a woman. Out of these 420 figures, 255 figures do not use any gesture(221 males, 34 females), 165 figures do gesticulate with either one or two hands (125 males, 40 females). 22 figures are dancing; I did not consider these movements as gestures in a strict sense. On the semantics of dancing: Catoni 2005; Heinemann 2016, 124–127. In some cases, it remains unclear whether a gesture is depicted, or whether the movement of the body is part of the figure’s action in a specific context (e.g., running, boxing); I counted such depictions as gestures, but they require further discussion which goes beyond the extent of this paper, cf. Günther forthcoming.

To raise a finger is also quite common (E: 15%), and this gesture is close to the speaking gesture (F: 5%); the speaking gesture might be understood as a more distinguished form of the raised finger. It is very remarkable, and strongly supports the figure’s role in a (communicative) interaction.Touching the head with one hand (G: 6%) is a typical gesture for strong emotions in tragedy-related vases when the hand covers the top of the head;42Tragedy-related examples: Naples, MAN 82113, Ilioupersis painter (Taplin 2007, 150–151, no. 47)and Naples MAN 80854, close to the Lycurgus painter (ibid., 196–198, no. 69); Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art 1991.1, Policoro painter (ibid., 123, no. 35). For the use of this gesture, see also Roscino 2019.or it may connote a “looking out” (aposkopein) when the hand touches the forehead to improve the sight of the figure.43Cf. Artemis looking out for a fury on an Apulian bell-krater by the Sarpedon painter in New York,MET 16.140, dating around 390 BC (Taplin 2007, 72–74, no. 14).All these gestures are very distinct and bring cognitiveframesfrom other contexts into the comedy-related vases.

A more diverse group of gestures includes touching something, either the clothes the figure is wearing (H: 4%) or another figure (J: 14%). Both gestures are meaningful since covering/uncovering the body is connected with specific connotations, especially in the case of female figures (i.e., actors wearing female masks and clothes, thus becoming “female” figures in the images). Obviously, to touch another figure is the most intensive means of communication possible.44Green 2001, 45.

The last group (K: 14%) assembles some rare gestures such as folding the hands,45Sicilian skyphos painted by the Manfria group: Gela, MAR 643 (see n. 36). For the gesture, cf.Green 2014, 116–118; Dohrn 1955.connecting thumb and index finger,46Bari, collection Malaguzzi Valeri 52, Apulian calyx-krater by the painter of Oxford G269 (Taplin 1993, 70–78, no. 11, pl. 14, 11).or resting one or two hands on the thighs.47See below.Another gesture is rare on comedy-related vases but is well known from other contexts: to raise both hands in front of the chest,48Comedy-related vases: Paestan bell-krater by Asteas in Berlin, Staatliche Museen F 3044 (Günther 2020, 91 fig. 2) and Contessa Entellina 1988, E856 (Taplin 2007, 263, no. 106). This gesture is common among old priestesses. For these figures as iconographic stock figures, cf. Moret 1975, 137–147. For a non-comic, tragic (?) example, see an Apulian bell-krater by the Sarpedon painter in New York, MET 16.140, dating around 390 BC (Taplin 2007, 72–74, no. 14). Emotions of fear and horror were still connected with this gesture in Roman times: Quint. Inst. 3.11.114; cf. Dutsch 2013, 416.often with spread fingers, is a common indicator for a strong emotion of fear and horror on tragedyrelated vases.49For the difficulties of identifying actors on stage, see Green 2002. Regarding the depiction of tragedies, some scholars argue that specific elements, like expressive gestures and an elaborate costume, are iconographic markers for tragedies (Taplin 1993, 21–29; 2007; Vahtikari 2014, 20–21),however, the modern conceptual border between depictions of tragic plays and mythological plots seems to be blurred. Luca Giuliani recently doubted that vase-paintings depict the staging of tragedies: Giuliani 2018 (cf. also id. 2013). For a comparison of “comic” and “tragic” vase-paintings,see id. 2018 and Günther 2020. For the iconography of tragedy-related vase-paintings, see (among many others) Roscino 2003 and Morelli 2001.

Looking at the total number of gesticulating figures, one may be surprised:Out of 420 figures on 225 comedy-related vases whose hands were not damaged,only 165 gesticulate (39%), while 255 do not (61%). The reasons for an absence of gesture are manifold. First, the figures may simply hold objects and thus cannot use their hands for gesturing (150; 59%); second, they may hold an object in one hand, but keep the other hand close to the body, usually wrapped in their clothes (40; 16%); third, they may refrain from using gesture, hiding their hands in their clothes, keeping them close to the body, sometimes with arms akimbo (18;7%). The absence of gestures does not mean an absence of communication. In particular, the figures who wrap their clothes tightly around their body follow the afore-mentioned ideal ofsōphrosynē. However, whether they seem to be a rather passive figure, a moral figure, or a helpless, dominated figure depends heavily on the context of the scene and on the body-language of the figure.

In the following paragraphs, I shall discuss the groups of gestures mentioned above in detail while examining the question as to what extent their meaning depends on the composition of the scene. According to the scope of this paper,I can only choose some examples and discuss them in detail, and I cannot take into account all varieties of the gestures and minor differences of function and meanings between different scenes.50An extensive and complete study will be available in Günther forthcoming.

Gestures A–F: Talking about hierarchy

Gestures A–F indicate that a figure refers to another figure (cf. ill. 1a/b), usually underlining the direction of communication, for instance, if a figure moves towards another figure with outstretched arms.51An example: Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 96.AE.113, Apulian bell-krater by the Cotugno painter,370–350 BC (Green 2001, 46 and 62, no. 11, fig. 8; 2012, 310–311 with fig. 14.11 and 335, no. 35);see: http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/29680 (30.04.2021).This includes a situation of greeting, especially when the hand is raised more or less in front of the body.Following the study of greeting gestures on Athenian vases,52Bogen 1969.the position of the hand and the arms in greeting gestures varies on comedy-related vases. A more general interaction takes place in vase-paintings where figures, usually two,stand opposite to each other and gesticulate; the number of such “conversational”scenes increases after 380 BC, and they become the most popular compositions between 360 and 340 BC. Since gestures are central elements in such scenes, one may ask whether gestures can reveal the content or meaning of the “conversation.”

An early example with a mythological background is a small bell-krater in Berlin, painted between 380 and 360 BC in Apulia (ill. 2).53Berlin, Staatliche Museen F 3045, Apulian bell-krater, height: 32cm, Eton Nika group, 380–360 BC(Trendall 1967a, 29, no. 21; Webster and Green 1978, 64, no. Ph 21; Taplin 1993, 82, no. 19,pl. 18, 19).The painting depicts two figures with comic masks and costumes. An actor with white hair sits on an altar on the left, behind him is a small tree. The altar with several blood splashes and a wreath on its front side as well as the tree refer to a sanctuary as the setting of the scene.54Green 2012, 307.The white-haired actor wears a Phrygian cap and anexōmisand leans slightly backwards while he raises his left hand towards the second figure,an approaching young warrior with sword, helmet, and cloak. The scene is likely a comic version of the murder of Priam by Neoptolemus during the Sack of Troy:55On the different interpretations, cf. Bieber 1920, 149, no. 111; 1961, 135; Walsh 2009, 94; Taplin 1993, 82. Due to the unique depiction of this scene, some uncertainty remains as to whether it is Priam sitting on the altar. However, the Phrygian cap makes the interpretation plausible, and the size and ornamentation of the headdress indicate that this figure is of some importance (king or leader).Furthermore, the occurrence of Neoptolemus killing Priam in Attic vase-painting provides frames by which to interpret the comic vase in this way, even if not intended by the painter, should the viewer possess the necessary background knowledge.Priam’s gesture might be either understood as an instinctive reaction to ward Neoptolemus off (hoping that his asylum on the altar protects his life), or as a smart attempt to persuade his enemy to refrain from attacking him.

Three observations point to the second interpretation. First, our supposed Priam raises the hand not higher than to his chin: he does not try to stop his enemy with his bare hand. Second, he spreads his index finger while his mouth is wide open, which implies that he is speaking, or at least that he is addressing Neoptolemus in some manner. Third, his hand is placed very closely to the hand of his opponent who holds the sword in a way that it points toward himself. This gives the impression that Priam is controlling the situation. If we take a close look at the composition, we learn that the central position of the figures’ hands emphasizes their meaning. Although the exact “reading” of Priam’s gesture is unclear, gesture and body-language visualize his reaction, and thus determine the plot behind the scene depicted. The content of the speech and Priam’s emotions are less important than the relationship of the figures expressed by the position of the gesture, that is, the information that Priam dominates this “conversation.” In this way, the image becomes intelligible for the viewer without the knowledge of a (postulated) tragicomic play mocking the murder of Priam.

Looking closer at the iconography of the painting, another twist becomes obvious: The composition (one figure sitting on an altar while another figure approaches) is reminiscent of comedy-vases depicting slaves seeking refuge from the punishment by their masters,56Berlin, Staatliche Museen F 3043 (Green 2012, 292–293 with fig. 14.1 and 331, no. 15); Malibu,J. Paul Getty Museum 96.AE.114 (ibid., 321 and 338, no. 52); New York, MET 24.97.104 (ibid., 296 and 331, no. 20). For the punishment of slaves, cf. Schumacher 2001, 277–278.but, if the interpretation of the scene is correct,King Priam is equated with the slave, and Neoptolemus with the master. On the one hand, this supports the idea that Priam speaks up in a clever and funny way,since this is the usual behavior of slaves in Attic comedy;57This is obviously the case for the cheeky slave Xanthias in Aristophanes’ Frogs, who complains about the heavy baggage he has to carry (Aristoph. Ran. 1–35), a motif present on comedy-related vases; see Biers and Green 1998.on the other hand,it inverts the status of Priam, obviously mocking him.58The negative and positive associations with the depiction of slaves in Greek art are discussed by Wrenhaven 2013.However, Neoptolemus also does not escape the parodistic intention of the image: Instead of the bellicose warrior who will not respect the sacrosanct nature of the sanctuary of Zeus, as we know him from Attic vase-paintings,59Cf., e.g., the famous hydria by the Kleophrades painter, an Attic red-figured hydria from Nola,Naples, MAN 81669 (ARV 189,74); Beazley Archive Pottery Database no. 201724.we see a beardless young man who is unable to land a blow on his defenseless foe.

Obviously, this painting is much more than a mere illustration of a play. It is a humorous piece of visual narration, and the viewer can “read” it on several levels. On a basic level, the viewer sees an old man with white hair threatened by a young warrior. Contrary to the viewer’s expectation, this horrific event is turned into a harmless conversation.60According to Aristotle, harmlessness is an important premise for comic effect (Aristot. Poet. 5.2 1449a 33–36). This assumption is still present in theories on humor in psychology (“arousal-safety humor”); see Ruch and Hofmann 2017, 95.The central gesture of the old man and the posture of the young warrior reveal that the old man successfully speaks up and defeats his armed enemy by words. This incongruency of mentalframesevoked by the figures causes a comic effect.61Incongruency is one of the basic types of humor (Kind 2017, 2–5). For comic incongruence caused by breaking and changing mental frames, cf. Wirth 2013.

Should the (ancient) viewer knew of the mythical Sack of Troy, he could recognize Priam via his Phrygian headdress, and understand the painting as a funny parody of this plot with a surprising change of the story. A viewer who was acquainted with the motif of Neoptolemus killing the Trojan king on vasepaintings, could add a further humorous level of mentalframes, and understand the image as a parody of serious vase-paintings. Such a viewer, well-informed of the current visual language, may have also understood the sophisticated blending of Priam and Neoptolemus with the depictions of slaves seeking refuge on an altar while their respective master approaches.62The existence of such a sophisticated viewer is not too unlikely since comedy-related vases mainly appeared in regions where red-figured vases were found in considerable numbers (cf.Günther forthcoming). However, we must not forget that we as modern researchers have access to the full range of ancient material from all regions and periods of time that survived until today. We must not assume such a panoptic view for the ancient viewer, and we have to take into account that many vase-paintings, available for the proposed ancient viewer, are now lost, including pictures on organic materials. Thus, our mental frames differ notably from the ancient viewers’ frames, and in reconstructing ancient frames, we also construct them from our modern point of view.

An ancient viewer familiar with concrete comedy performances may have recognized a nowadays lost play in the painting, and he might have joyfully remembered the amusing staging.63Taplin 1993, 90.His mental framework may have also included a tragedy on the Sack of Troy, and he might have “read” the image as a comic inversion of this tragic play. He might have understood the allusion of the painter to the refuge-seeking slave, which he knew from a comic performance.Or, he might at least have identified the comic costumes and, even without knowing a matching comedy, have realized that the scene is somehow linked to comedy, which supposes that this image has a funny content, and he will have easily “read” a funny plot, as I have already elaborated. In particular, in case he was not too familiar with comedy-related vases, he might have enjoyed the“metatheatrical”64On the terminology, cf. ibid., 67–68. He understands the metatheatrical effect of the images as a parallel to the breaking with the illusion in the play. Comedy-related vase-paintings highlight the artificial character of the costume and thus reveal theatricality of the scene depicted in a selfreferential manner.effect of the painting: the detailed rendering of the costumes and masks by the painter reveals the fictionality both of the scene and the image.65Giuliani 2013 and 2018. The author proposes that the metatheatrical effect (cf. n. 64) is responsible for the comic effect of the images, while the reason that costumes and masks in tragedy-related vases never appear is to avoid humor and remain serious.This causes a further comic incongruency and contributes to the humor of the painting.

Which “reading(s)” or levels of understanding were available to an ancient viewer depends on his or her mentalframes, and accordingly to the knowledge,experiences, and expectations that can be applied. It is impossible to determine who understood which connotations and allusions, and on which level. However,it is interesting that the vases indeed offered such different “readings,” even though not all viewers could possibly understand all of them; it is sufficient for a comic effect if they understood them partly, or just some basic hints. The most intensive comic effect will, of course, occur if all these levels interfere with each other, if allusions to comedy, tragedy, iconography, myth, meta-theatricality,and so forth are blended with each other in the mind of the perceiver. But even for a viewer who could not access all levels, the painting still offered some funny “readings,” even on the basic level, i.e., an old man from an altar defeats an armed young warrior with words instead of weapons. This shows that the painting has a certain potential to evoke differentframeswithin its recipients, and that this contributes to a complex and funny visual narration.

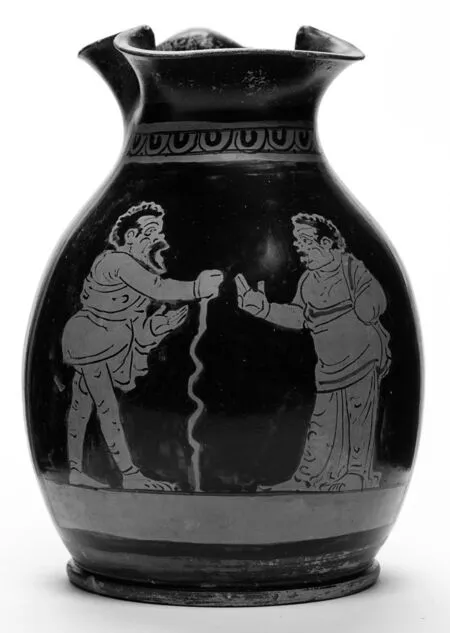

A second example may illustrate to what degree the “reading” of a gesture and its meaning within the narrative depends on its position in the image and the body-language of the figures. On an oenochoe in Sydney,66Sydney, Chau Chak Wing Museum, The University of Sydney NM75.2 (Green 2014, 104, fig. 7;CVA The Nicholson Museum Sydney (1) pls. 48–49). “comic situation of a man in confrontation with his domineering wife (…) her right arm and hand extended in a more aggressive speaking gesture.She appears to be winning the argument.” (CVA The Nicholson Museum Sydney (1) pls. 48–49).painted by the Apulian Truro painter between 360 and 340 BC, we see two actors facing each other (ill. 3). The left actor wears a comic mask with dark hair and beard, he has wrapped his cloak closely around his body and holds a staff in his right hand.Cloak (himation) and staff are the typical attribute of an (Athenian) citizen and thus indicate an appropriate social status.67Aristoph. Vesp. 31–35. Cf. Green 2001; Compton-Engle 2015, 68; Franceschini 2018, 151–155.The figure on the right is an actor with female mask and clothes; this woman has short hair, like the one of nurses and female slaves.68For depictions of nurses, cf. Schulze 1998, 61–68. Nurses on vases without comic context with short white hair: Basel, collection Cahn HC 236, fragment of an Apulian pelike (?), Sisyphos painter(Schulze 1998, A V 35, pl. 28, 3). Thracian nurse with short hair and tattoos: London, British Museum E 509, 1; red-figured fragment of the Sisyphos painter (Schulze 1998, no. A V 34 pl. 28, 4). Nurses usually appear on tragedy-related vases; Schulze assumes that these figures were heavily influenced by the character of the old nurse in theatrical plays (Schulze 1998, 77).Her left arm is akimbo and wrapped in a cloak while she slightly rises her right arm using the speaking gesture and opens her mouth: She speaks up to the man in front of her. He reacts and exposes the left hand which would otherwise have been covered by the cloak; he turns his palm up, and his fingers point towards the woman’s head.

Such compositions are quite common between 360 and 340 BC. Women or slaves speak up and invert the social order. Nasty women/wives seem to dominate their helpless husbands,69Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum IV 466, SK 182, 176 (Green 2014, 105, fig. 8); Würzburg,Martin-von-Wagner-Museum H 5846 (Hughes 2012, 143, fig. 44). Possibly also a fragment in Heidelberg, collection of the university U8 (CVA Heidelberg (2) pl. 75, 1).and cheeky slaves refuse to carry the heavy baggage of their masters;70Bari, MAN 2795 (Trendall 1967a, 49, no. 74, pl. 6), Taranto, MAN 20353 (ibid., 68, no. 136, pl.9a), Malibu, J. P. Getty Museum 96.AE.238 (Biers and Green 1998, 90, pl. 18, 3).they usually raise their gesticulating hands higher than the hands of the master. The dominating gesture indicates as to who controls the discussion.In these scenes, the painters not only adopt “conversational” scenes common in red-figured vase-painting in general,71Especially on the reverses of Attic and southern Italian vases (also of comedy-related vases), cf.Franceschini 2018; however, gestures appear frequently on the obverses, e.g., on luxurious Apulian vases, cf. Giuliani 1995; Schulze 2000.but also apply comic motifs of which we know from the plays of Aristophanes.72For slaves discussing with their masters, see Biers and Green 1998; for discussing slaves, cf. Green 2015, 66–69; for dominating women, cf. id. 2014, 105–106.The woman on the oenochoe in Sydney with her short hair and aggressive body-language undoubtedly possesses quite a masculine look. Yet, does she really dominate her master? Not all such scenes imply that the figure lower in the hierarchy dominates the other; in some cases,both figures do not gesticulate, or it is the master, not the slave, who dominates the discussion,73Paris, Louvre K 18 (Trendall 1967a, 41, no. 52); see: https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010274210 (30.04.2021); Matera, Museo Domenico Ridola 164507 (Green 2015, 66–73).or the man, not the woman, respectively.74An oinochoe in Syracuse from the 3rd quarter of the 4th century BC depicts a gesticulating woman,but the man opposite her raises his hand higher: Syracuse, MAR Paolo Orsi 25166 (Pace 1938, 471,fig. 341). Taranto, MAN 54724 (Green 2014, 108, figs. 9a–b). In general, female acting figures on comedy-related vases follow social conventions: they stand close to doors (for the oikos (house) as the center of a women’s duties and activities, see, e.g., Xen. Oec. 7.22–25), wear long dresses with heavy overfolds, and restrict themselves to watching the action carried out by men.In the case of the oenochoe in Sydney, the woman seems to be the more powerful conversation partner, since she uses the speaking gesture, raises her hand higher than the very low left hand of the man, opens her mouth, and is shown in three-quarter view.The man’s body is visible only in profile, which reduces his communicative potential in respect to the viewer. His right arm covers a part of his body, and the gesticulating left hand is barely visible. Nonetheless, the painter chose this specific projection of the figure into the second dimension. What seems to be an unfavorable decision at first sight is, in fact, a thoughtful presentation of the figure. The man seems to be the weaker conversation partner, but, at the same time, he still dominates the image; note that he is taller than her, and that his fist,holding the staff, is higher than her speaking gesture. In addition, the staff marks a clear and strong border between the figures: he is keeping her at a distance.

Thus, I would like to propose an alternative interpretation of the vase. The effect of this painting might not be juxtapose a strong woman and a weak man,but rather to make the viewer guess as to who might win the argument. However,this is not the only funny twist of the painting. Man and woman imitate each other in terms of their posture:75In this detail, the painting is exceptional among all other depictions of a man and woman opposed in Apulian comedy-related vase-paintings.Both put the right leg forward and bend toward each other, they stretch out the right hand and keep the left arm close to their body. Even their hairstyles look strikingly similar. Comparable with the case of the Apulian askos in Malibu discussed above, the viewer may conclude that the(Greek) citizen is in no regard the better of his cheeky female servant.76Short hair indicates the status of a female servant, often a nurse (with white hair). Cf. Schulze 1998, 61–68.

Both examples show that the way viewers can “read” the meaning of gestures used in conversations on comedy-related vases depends heavily on the bodylanguage of the figures and the position of arms and hands in relation to each other. Gestures as pictorial elements serve to contrast the figures and build up hierarchies by which to visualize to what extent a figure dominates the conversation, or to play with exactly these expectations of the viewer. The inversion of hierarchies causes a comic effect, but the manifold cognitiveframesalso lead to a funny twist within the image which does not depend on a specific comic play. The concrete meaning of a gesture, e.g., the speaking gesture, is less important, and, were we to replace the speaking gesture with an open hand as in the case of the oenochoe in Sydney, or to replace the gesture of Priam with the speaking gesture, then the meaning of the image would not much change.Thus, in the case of these conversational gestures, the context and especially the relationship between the figures as visualized by gestures and body-languages are crucial for the narration.

Gestures G–L: Talking about emotions

Gestures G–L are diverse in nature, but different from the rather unspecific movements which we discussed in the last paragraph (the speaking gesture is very conventional, but nonetheless indicates only the fact that a figure is speaking), since the positions of arms and hands are more distinct. These gestures are not in all cases well-known, e.g., from Attic vase-paintings. Yet, the more specific movements may imply a more precise meaning, and it is, indeed,possible in many cases to suppose a meaning77Green 2014; 2001.which mainly expresses the emotional state of a figure, and hence involves further cognitiveframes. I should like to demonstrate this by way of two examples.

A Lucanian bell-krater in Sydney is one of the earliest so-called phlyax vases, dating to around 400 BC (ill. 4).78Sydney, Chau Chak Wing Museum, The University of Sydney NM2013.2, Lucanian bell-krater,height: 28.3cm, diam.: 28.8cm, Creusa painter, 410–390 BC (CVA Nicholson Museum (2) pl. 19;Green 2014, 94–100).On the left, a woman with short hair approaches; she nearly touches her chin with her left hand while her right addresses a second figure with a speaking gesture. In front of her lies another woman on aklinē, her upper torso and head nearly turned to a frontal view. She rests her left arm on a pillow and touches her neck with the right hand. In contrast to the short-haired woman on the left, she wears a more elaborate, girdled chiton,a diadem which indicates a high social status, and has soft, curly hear. The humor of this painting may lie in the adaption of a clearly tragic and dramatic motif within a comic setting. A female servant or nurse brings her mistress bad news;it might be Phaedra being informed about the death of her beloved Hippolytus.79Green 2014, 111–114 and 121. He suspects a comedy by Aristophanes: ibid., 130–131. Whether this is the (only) plausible interpretation of the scene must remain open.As in the vase-paintings discussed above, the speaking gesture is placed in the center of the composition and visualizes the importance of the message, although the mouth of the servant is closed. The gesture of her left hand is known from other non-comic vase-paintings, denoting a manner of surprise or astonishment.80Quite similar are the gesture of a nurse on an Apulian Loutrophoros in Basel, Antikenmuseum S21, close to the Laodamia painter, 340 BC (Taplin 2007, 111, no. 31) and a Sicilian lebes gamikos in Syracuse, MAR Orsi 47099, Lentini painter; cf. Trendall 1967b, 589, no. 27, pl. 228.The gesture of touching the head mainly appears on tragedy-related vases and indicates a strong emotional involvement, i.e., shock or dismay. On comedyrelated vases, we find this gesture only three times, including this bell-krater, and it is significant that on a well-known krater in Bari, the “chorēgosvase,” a figure with tragic costume labeled “Aigisthos” uses this gesture and thus indicates the non-comic origin of hispersona.81Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 96.AE.29 (Taplin 1993, 55–63, no. 9.1 and fig. 9.1; Giuliani 2013,11–39). The other vase is a Sicilian calyx-krater by the painter Asteas in Lipari, MAR Eoliano 927(Green 2012, 321–322 and 339, no. 54).The half-lying position of the lady’s body supports the impression that her emotional state has taken control over her movements. She sinks down on the pillow and does not coordinate her left hand.Since she has turned her upper body and head to an almost frontal view, her helpless attitude attracts the viewer’s attention.

Not only the message of the servant is important in this vase-painting, but also the social status visualized by clothes and hairstyle. In particular, the emotions of the figures are important to understand the plot, while the explicit depiction of tragic and dramatic emotions and their incongruence with the comic context cause a comic effect.

The krater in Sydney is the earliest comedy-related vase-painting with the speaking gesture known. Harald Schulze argued that the speaking gesture in southern Italian vase-paintings derives from both rhetoric and stage performances, and was introduced by the painters due to a need for an unambiguous sign for speaking.82Schulze 2000, 135.However, the speaking gesture on early comedyrelated vases is rare, and it is only between 360 and 340 BC, when compositions with two interacting actors become popular (see above), that we find speaking gestures more regularly. At the same time, speaking gestures appear in vasepaintings without a connection to comedy; two of them derive from painters who also produced comedy-related vases.83A fragment of a bell-krater by the Hoppin painter, Basel market (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978,438, no. 5/79a), a column-krater by the Dijon painter in Berlin, Staatliche Museen F 3289 (Trendall and Cambitoglou 1978, 154, no. 6/161, pl. 48,6, reverse).After the middle of the 4th century BC,speaking gestures are mainly used for messenger figures, evoking the messenger speeches of tragic performances,84See Green 1999.while the speaking gesture in this period is rare in comedy-related vase-paintings.85Bari, MAN 4073 (Bieber 1961, 136, fig. 498); Leipzig, collection of the university T 5126 (Hughes 2012, 131, fig. 32); London, British Museum F 233 (Green 2015, 45–51, figs. 1–2); see: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1865-0103-29 (30.04.2021).

Hence, the question arises as to whether H. Schulze was right to assume that the speaking gesture on southern Italian red-figures vases derives from rhetoric and theater. The influence of theater seems very likely at first sight86Schulze 2000, 134–135; Hughes 2012, 160 argues that comedy-related vase-paintings inherited the speaking gesture from tragic performances.since the earliest depiction of this gesture on the krater in Sydney is linked both to comedy and tragedy, and since the most frequent depictions of vase-paintings refer to tragedy.However, its regular appearance on vases without links to stage performances and its reduction to tragic vase-paintings, especially to messenger figures, in the second half of the 4th century BC (i.e., later than the “conversional” scenes on comic vases) together indicate that the use of the speaking gesture does not per se refer to stage performances. On the contrary, it seems that the popularity of the speaking gesture on vases without any link to theatrical performances as a strong visual indication for a conversation stimulated the preference of this gesture on comedy-related vases between 360 and 340 BC. Thus, the bell-krater with Phaedra and her nurse as the earliest example of the speaking gesture on comedyrelated vases known does not so much prove the use of this gesture on stage at this time, but rather the employment of it by a vase painter trying to visualize speech as a crucial part of the image’s narrative. Supplementary to the thoughts in the introduction of this paper, it must be added that the depiction of certain gestures was not only influenced by theater performances or the rhetorical stage,but may also be the result of a transformation of gestures, body-languages, and postures into an iconographic tradition.

An Apulian bell-krater in Copenhagen87Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark 15032, Apulian bell-krater by the Jason painter, 370–350 BC, height: 28cm, diam.: 31cm (Green 2001, 49–51, no. 19, fig. 10).(ill. 5) painted between 370 and 350 BC displays a wooden stage with a simple staircase, four columns, and a curtain between them. An Ionic column on the stage, which seems to support the decoration on the rim, indicates that this scene takes place in a house. Green has reconstructed the plot of this interesting image:88Ibid., 50–51; see ibid. for further discussion of the depiction of hetairai on comedy-related vases.The female on the left, standing close to the end of the stage, is ahetaira, recognizable by her fancy hairstyle and the way she lets her cloak slip down. The man in the middle, a Greek citizen withhimationand staff, might be her former lover, tricked by her. A slave carries a big chest out of the house (the column very likely indicates the boundary between the house’s interior and exterior), and the body-language of the citizen gives the impression of pure astonishment. He seems to collapse, with the neck overextended, the knees bending, and the cloak slipping down; although he puts his right hand on his knee, he cannot stabilize his body, as his weak grip around the walking-stick demonstrates.

Resting the hand on the thighs is a gesture that reappears on a comedy-related vase, a calyx-krater in Lipari painted by the Paestan painter Asteas,89MAR Eoliano 927 (Green 2012, 321–322 and 339, no. 54). In turn, a slave who will be beaten with a stick is shown in this posture on a Lucanian calyx-krater in Berlin (Berlin, Staatliche Museen und Antikensammlung F 3034, cf. n. 36).whereby an old actor bends his knees and puts his hands on his thighs while staring at a naked female dancer. Presumably, the gesture in this Paestan painting illustrates how the figure is overwhelmed by the erotic presentation, and thus we cannot exclude an erotic connotation of the gesture on the Apulian vase, especially since the citizen’s love for thehetairaprobably forced him into the calamity depicted. On the other hand, he does not look at thehetairaand turns away from her towards the house, and thus the gesture seems to be a direct reaction to what is happening inside. However, it is not clear whether the slave is stealing the chest, whether thehetairahas deceived the citizen to give away his property,or whether the chest belongs to thehetaira, and she is simply leaving the (his?)house. We cannot even exclude that the man carrying the chest is not a slave, but an accomplice of the woman or her (new?) lover.

What we can tell based on the arrangement of the pictorial elements is the following: The man carrying the chest brings the explanation for the breakdown of the citizen. Still, the focus lies on thehetairaand the citizen, and the painter contrasts their postures to the extreme. While the old man breaks down, she is standing upright. In turning only her head but not her body towards the citizen,she looks down on him. Her movements are relaxed: She lifts the right arm slightly with palm up, and her left hand fixes the cloak while spreading the index finger. Due to her posture and her open mouth, she seems to deliver a speech towards the (invisible) audience, particularly since her head is nearly shown in frontal view, assuming that the image depicts an actual stage performance.90Green 2001, 51.We cannot prove whether this explanation is correct, but the fact that she turns toward the viewer gives the impression of strength and control over the incident happening in front of her.91That the man with the chest is shown in the same perspective might indicate that he belongs to her,whether as a servant or a lover.Similar to the “conversational” scenes with men and women previously discussed, the humor of this image lies in the inversion of hierarchies and the dominance of the (seemingly) less powerful woman(hetaira) over the citizen. Thus, the painting may be understood as an extended“conversational” piece, turning upside down social hierarchies.

The gestures of the servant and the lady on the Lucanian krater in Sydney and the combination of gesture and body-language in the case of the citizen on the Apulian krater in Copenhagen are more specific than the “conversational”gesture on these and other vases. However, their interpretation does not result from a highly conventional connotation of the body’s movement. The posture,the position of arms and fingers respectively, still allows a range of “readings,”but narrower than in case of the “conversational” gestures. The exact meaning of the gesture (e.g., whether astonishment, horror, or despair) remains unclear,and can only be reconstructed in combination with the other pictorial elements.In this sense, these “specific” gestures offer a certain range of interpretations, or cognitiveframes, that, however, still depend on the whole cognitive framework of the image. The more specific gestures discussed here contribute less to the deciphering of the communication process and (social) hierarchies, but rather visualize the emotional state of the respective figure, and, indeed, of very strong emotions. Those extreme emotions expressed by the gestures, as well as the gestures themselves, originate from tragedy-related vases.92Gestures known from tragedy-related vases are also in use in the following comic vases: Milazzo,Antiquarium 11039 (former Messina, Soprintendenza, no. 44); Lentini, MAR (no inv.-no.), Green 2012, 319, no. 47. On the krater in Lentini, the pairing of an old woman and an old man with their hands on their chest mirrors the figures of nurse and paidagogos, common on tragedy-related vases.For the figures and the gesture with hand on the chest, cf. Schulze 1998, pl. 43, 3–4 (Princeton University Art Museum y 1989-29). For nurses and paidagogoi, cf. ibid., 73–77 and 131, no. A V 68.Schulze does not interpret the male acting figure on the left as a paidagogos, probably because his hair is not white, i.e., he is not explicitly characterized as an old man. Trendall and Webster 1971, 136 suggest that he is Aleos, the father of Auge (who is possibly the young woman Heracles is interested in), and thus an old man. Nonetheless, even as a father and not a paidagogos, he fulfills the same role as a parental, emotional involved bystander. Interpreted as a protagonist: Green 2012, 115.The painters have transferred them into the context of a comic scene, this causing comic incongruencies in and of itself.

Conclusion

Gesture and body-language as pictorial elements form a fundamental part of interaction and communication within comedy-related vase-paintings. They lead the gaze of the viewer through the image, and form the starting points of the narration visualized in the paintings. Among the different gestures used in comedy-related vases, two main groups could be identified.

The first of these is constituted by quite unspecific gestures which often appear in “conversational” scenes. These not only illustrate a communication process,but also evoke comic effects in playing with the viewers’ expectations regarding the social status and hierarchies of the figures. The position of the gestures within the composition and their combination with the body-language, especially active/passive movements, are important for the image’s narrative, but not their concrete meaning per se.

Second are more specific gestures which are often combined with the“conversational” gestures of the first group. They visualize the emotions of the figures, which are often strong reactions to their environment. Important is the intensity of the feeling that they transport, and what this contributes to the visual narration. However, similar to the first group of gestures, they are not fully conventionalized, but rather display variation within a certain range of meanings,mostly expressing strong, less than clearly defined, negative feelings. Thus, the gestures of the second group must also be “read” together with the other pictorial elements. Interestingly, these gestures (but also the speaking gesture which belongs to the first group) have strong links to tragedy-related vases, and it seems that the incongruence of “tragic” gestures and “comic” figures contributes to the humor of these images.

Although the composition is necessary for the understanding of the meaning and the function of the gestures, the choice of gestures is not arbitrary. The painters use the spectrum of cognitiveframeswhich gestures evoke in the image to create an attractive and unique narration, combiningframeslike social status, behavior,sōphrosynē, gender roles, theater performances, and iconographic conventions. Thus, comedy-related vases do not directly depict stage performances, but rather develop their own narratives to represent the genre of comedy in a unique way. As a result, they are a medium of comedy in its own right – a visual medium of comedy.

Bibliography

Beazley, J. D. 1963.

Attic Red-Figure Vase-Painters. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Bieber, M. 1920.

Die Denkmäler zum Theaterwesen im Altertum. Berlin: De Gruyter.—— 1961.

The History of the Greek and Roman Theater.2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Biers, W. R. and Green, J. R. 1998.

“Carrying Baggage.”Antike Kunst41: 87–93.

Bogen, K. 1969.

Gesten in Begrüßungsszenen auf attischen Vasen. Bonn: Habelt.

Bosher, K. (ed.). 2012.

Theater Outside Athens. Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy.Cambridge et al.:Cambridge University Press.—— 2013.

“‘Phlyax’ Slaves: From Vase to Stage?” In: B. Akrigg and R. Tordorff (eds.),Slaves and Slavery in Ancient Greek Comic Drama. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 197–208.

Bremmer, J. 1992.

“Walking, Standing and Sitting in Ancient Greek Cultures.” In: id. and H. Roodenburg (eds.),A Cultural History of Gesture. From Antiquity to the Present Day.Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 15–35.

Carpenter, T. 2003.

“The Native Market for Red-Figure Vases in Apulia.”Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome48: 1–24.—— 2009.

“Prolegomenon to the Study of Red-Figure Pottery.”American Journal of Archaeology113: 27–38.

Catoni, M. L. 2005.

Schemata. Comunicazione non verbale nella Grecia antica. Studi 2. Pisa:Edizioni della Normale.

Compton-Engle, G. 2015.

Costume in the Comedies of Aristophanes. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.

Csapo, E. 1986.

“A Note on the Würzburg Bell-Crater H 5697. Telephus Travestitus.”Phoenix40: 379–392.—— 1993.

“A Case Study in the Use of Theatre Iconography as Evidence for Ancient Acting.”Antike Kunst36: 41–58.—— 2010.

Actors and Icons of the Ancient Theater.Chichester et al.: Wiley-Blackwell.

Csapo, E. et al. (eds.). 2014.

Greek Theatre in the Fourth Century B.C.Berlin et al.: De Gruyter.

Dally, O. 1997.

“Review of Giuliani 1995.”Bonner Jahrbücher197: 473–476.

Dearden, C. 2012.

“Whose Line is it Anyway? West Greek Comedy in its Context.” In: K. Bosher(ed.),Theater Outside Athens. Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 272–288.

Diggle, J. (trans.). 2004.

Theophrastus: Characters. Edited with Introduction, Translation and Commentary. Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries 43. Cambridge et al.:Cambridge University Press.

Dohrn, T. 1955.

“Gefaltete und verschränkte Hände. Eine Studie über die Gebärde in der griechischen Kunst.”Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts70:50–80.

Dutsch, D. 2013.

“Towards a Roman Theory of Theatrical Gesture.” In: G. W. M. Harrison and V. Liapis (eds.),Performance in Greek and Roman Theatre. Leiden: Brill, 409–431.

Fehr, B. 1979.

Bewegungsweisen und Verhaltensideale. Physiognomische Deutungsmöglichkeiten der Bewegungsdarstellung an griechischen Statuen des 5. und 4. Jhs. v. Chr.Bad Bramstedt: Moreland.

Franceschini, M. 2018.

Attische Mantelfiguren: Relevanz eines standardisierten Motivs der rotfigurigen Vasenmalerei.Zürcher Archäologische Forschungen 5. Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Freese, J. H. (trans.). 1926.

Aristoteles. The“Art”of Rhetoric. Loeb Classical Library 193. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Giuliani, L. 1995.

Tragik, Trauer und Trost. Bildervasen für eine apulische Totenfeier.Berlin:Staatliche Museen zu Berlin-Preussischer Kulturbesitz.—— 2013.

Possenspiel mit tragischem Helden. Mechanismen der Komik in antiken Theaterbildern. Historische Geisteswissenschaften. Frankfurter Vorträge 5. Göttingen:Wallstein Verlag.—— 2018.

“Theatralische Elemente in der apulischen Vasenmalerei: Bescheidene Ergebnisse einer alten Kontroverse.” In: U. Kästner and S. Schmidt (eds.),Inszenierung von Identitäten. Unteritalische Vasenmalerei zwischen Griechen und Indigenen.Beihefte zum Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum 8. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Kommission beim Verlag C. H. Beck, 108–118.

Goffman, E. 1974.

Frame Analysis. An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Cambridge, MA:Harvard University Press.

Graf, F. 1992.

“Gestures and Conventions: The Gestures of Roman Actors.” In: J. Bremmer and H. Roodenburg (eds.),A Cultural History of Gesture. From Antiquity to the Present Day. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 36–58.

Green, J. R. 1994.

Theatre in Ancient Greek Society.London & New York: Routledge.—— 1997.

“Deportment, Costume and Naturalism in Comedy.”Pallas47: 131–143.—— 1999.

“Tragedy and Spectacle of the Mind. Messenger Speeches, Actors, Narrative, and Audience Imagination in Fourth-Century BCE Vase-Painting.” In: B. Bergmann and C. Kondoleon (eds.),The Art of Ancient Spectacle. Proceedings of the Symposium“The Art of Ancient Spectacle”, 10.–11.05.1996, Washington. New Haven: Yale University Press, 37–63.—— 2001.

“Comic Cuts: Snippets of Action on the Greek Comic Stage.”Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies45: 37–64.—— 2002.

“Towards a Reconstruction of Performance Style.” In: P. E. Easterling and E. Hall (eds.),Greek and Roman Actors. Aspects of an Ancient Profession.Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 93–126.—— 2003.

“Smart and Stupid. The Evolution of Some Masks and Characters in Fourth-Century Comedy.” In: J. Davidson and A. Pomeroy (eds.),Theatres of Action:Papers for C. Dearden. Auckland: Polygraphia, 118–132.—— 2012.

“Comic Vases in South Italy. Continuity and Innovation in the Development of a Figurative Language.” In: K. Bosher (ed.),Theater Outside Athens. Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press,289–342.—— 2014.

“Two Phaedras: Euripides and Aristophanes?” In: S. D. Olson (ed.),Ancient Comedy and Reception. Essays in Honor of J. Henderson. Berlin et al.: De Gruyter, 94–131.—— 2015.

“Pictures of Pictures of Comedy. Campanian Santia, Athenian Amphitryon, and Plautine Amphitruo.” In: J. R. Green and M. Edwards (eds.),Images and Texts.Papers in Honour of E. Handley. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies Supplement 129. London: Institute for Classical Studies, 45–80.

Günther, E. 2020.

“Heterogenität, Inkongruenzen, Widersprüche – tragödien- und komödienbezogene Vasenbilder aus Unteritalien und deren Bilderzählung.“ In: J. Bracker(ed.),Homo Pictor. Image Studies and Archaeology in Dialogue. A Conference of the Institute for Archaeological Studies, University of Freiburg, 28.–30.06.2018.Freiburger Studien zur Archäologie und visuellen Kultur 2. Heidelberg:Propyläum, 79–107.—— 2021.

“Mehrdeutigkeiten antiker Bilder als Deutungspotenzial. Zu den Interdependenzen von Affordanzen undframesim Rezeptionsprozess.” In: Günther and Fabricius 2021, 1–40.—— forthcoming.

Komische Bilder. Bezugsrahmen und komisches Potenzial unteritalischer Komödienvasen.Philippika. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Günther, E. and Fabricius, J. (eds.). 2021.

Mehrdeutigkeiten. Rahmentheorien und Affordanzkonzepte in der archäologischen Bildwissenschaft. Philippika 147. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Heinemann, A. 2016.

Der Gott des Gelages. Dionysos, Satyrn und Mänaden auf attischem Trinkgeschirr des 5. Jahrhunderts v.Chr.Image & Context 15. Berlin et al.: De Gruyter.

Hughes, A. 1996.

“Comic Stages in Magna Graecia: The Evidence of the Vases.”Theatre Research International21: 95–107.—— 2006.

“The Costumes of Old and Middle Comedy.”Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies49: 39–68.—— 2012.

Performing Greek Comedy. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.

Jucker, I. 1956.

Der Gestus des Aposkopein. Ein Beitrag zur Gebärdensprache in der antiken Kunst. Zürich: Juris-Verlag.

Kind, T. 2017.

“Komik.” In: U. Wirth (ed.),Komik. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch.Unter Mitarbeit von J. Paganini. Stuttgart: Metzler, 2–6.

Le Guen, B. 2001.

Les associations de Technites Dionysiaques à l’epóque hellénistique. Études d’archéologique Classique 12. Nancy: Association pour la diffusion de la recherche sur l’antiquité.

Maffre, J.-J. 2000.

“Comédie et iconographie. Les grands problems.” In: J. Leclant and J. Jouanna(eds.),Le théâtre grec antique. La comédie. Actes du 10ème colloque de la Villa Kérylos à Beaulieu-sur-Mer, 01.–02.10.1999. Cahiers de la Villa Kérylos 9.Paris: Académie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres, 269–315.

Maier-Eichhorn, U. 1989.

Die Gestikulation in Quintilians Rhetorik.Europäische Hochschulschriften Reihe 15, Klassische Sprachen und Literaturen 4. Frankfurt am Main & New York:P. Lang.

Marshall, C. W. 2001.

“A Gander at the Goose Play.”Theatre Journal53/1: 53–71.—— 2006.

The Stagecraft and Performance of Roman Comedy. Cambridge et al.:Cambridge University Press.

Masséglia, J. 2015.

Body Language in Hellenistic Art and Society.Oxford: Oxford University Press.McNiven, T. 1989.

Gestures in Attic Vase Painting. Use and Meaning. Ann Arbor: UMI.

Minsky, M. 1980.

“A Framework for Representing Knowledge.” In: D. Metzing (ed.),Frame Conceptions and Text Understanding. Berlin et al.: De Gruyter, 1–25.

Morelli, G. 2001.

Teatro attico e pittura vascolare. Una tragedia di Cheremone nella ceramica italiota. Spudasmata 84. Hildesheim: G. Olms.

Moret, J.-M. 1975.

L’Ilioupersis dans la céramique italiote. Les mythes et leur expression figurée au IVe siècle. Bibliotheca Helvetica Romana 14. Rome: Institut suisse de Rome.

Neiiendam, K. 1992.

The Art of Acting in Antiquity. Iconographical Studies in Classical, Hellenistic and Byzantine Theatre.Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

Neumann, G. 1965.

Gesten und Gebärden in der griechischen Kunst.Berlin: De Gruyter.

Pace, B. 1938.

Arte e civiltà della Sicilia anticaII. Milan et al.: Società anonima editrice Dante Alghieri.

Richter, T. 2003.

Der Zweifingergestus in der römischen Kunst. Frankfurter archäologische Schriften 2. Möhnesee: Bibliopolis.

Robinson, E. G. D. 2004.

“Reception of Comic Theatre Amongst the Indigenous South Italians.”Mediterranean Archaeology17: 193–212.

Roscino, C. 2003.

“L’immagine della tragedia. Elementi di caratterizzazione teatrale ed iconografia nella ceramica italiota e siceliota.” In: L. Todisco (ed.),La ceramica figurata a soggetto tragico in Magna Grecia e in Sicilia. Rome: G. Bretschneider, 223–357.—— 2019.

“Il gesto di Egisto e l’eisangelia: Ancora sul vaso apulo dei Choregoi.”Ostraka28: 191–210.

Ruch, W. and Hofmann, J. 2017.

“Psychologie, Medizin, Hirnforschung.” In: U. Wirth (ed.),Komik. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch.Unter Mitarbeit von J. Paganini. Stuttgart: Metzler,89–101.

Schönheit, L. 2016.

“Hinter die Maske geblickt: Unteritalische Vasenbilder als Identitätsvermittler.”Visual Past3/1: 421–447.—— 2018.

“Theaterbilder im Spannungsfeld zwischen Italioten und Italikern.” In: U. Kästner and S. Schmidt (eds.),Inszenierung von Identitäten. Unteritalische Vasenmalerei zwischen Griechen und Indigenen. Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Beiheft 8.Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 119–127.

Schulze, H. 1998.

Ammen und Pädagogen. Sklavinnen und Sklaven als Erzieher in der antiken Kunst und Gesellschaft. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.—— 2000.

“Redende Personen in sprechenden Bildern. Darstellung von Rede und Dialog in der unteritalischen Vasenmalerei.” In: C. Neumeister and W. Raeck (eds.),Rede und Redner. Bewertung und Darstellung in den antiken Kulturen. Kolloquium,14.–16.10.1998. Frankfurter archäologische Schriften 1. Möhnesee: Bibliopolis,119–150.

Schumacher, L. 2001.

Sklaverei in der Antike: Alltag und Schicksal der Unfreien.Beck’s archäologische Bibliothek. Munich: C. H. Beck.

Sittl, C. 1870/1970.

Die Gebärden der Griechen und Römer. Reprint of the 1870 ed. Hildesheim &New York: Olms.

Stansbury-O’Donnell, M. 1999.

Pictorial Narrative in Ancient Greek Art.Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.—— 2010.

Looking at Greek Art.Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.—— 2014.

“Composition and Narrative on Skyphoi of the Penelope Painter.” In: A. Avramidou and A. Shapiro (eds.),Approaching the Ancient Artifact. Representation,Narrative, and Function. A Festschrift in Honor of H. A. Shapiro. Berlin et al.:De Gruyter, 373–383.

Steiner, A. 2007.

Reading Greek Vases.Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.

Taplin, O. 1987.

“Phallology, Phlyakes, Iconography and Aristophanes.”Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society33: 92–104.—— 1993.

Comic Angels and Other Approaches to Greek Drama through Vase-Paintings.Oxford: Oxford University Press.—— 2007.

Pots and Plays. Interactions between Tragedy and Greek Vase-Painting of the Fourth Century B.C.Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.—— 2012.

“How was Athenian Tragedy Played in the Greek West?” In: K. Bosher (ed.),Theater Outside Athens. Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 226–250.

Todisco, L. 2012.

“Myth and Tragedy. Red-Figure Pottery and Verbal Communication in Central and Northern Apulia in the Later Fourth Century BC.” In: K. Bosher (ed.),Theater Outside Athens. Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy. Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 251–271.

Trendall, A. D. 1967a.

Phlyax Vases.2nd ed. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies Supplement 19. London: Institute for Classical Studies.—— 1967b.

The Red-Figured Vases of Lucania, Campania and Sicily. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Trendall, A. D. and Cambitoglou, A. 1978.

The Red-Figured Vases of Apulia1:Early and Middle Apulian.Oxford:Clarendon Press.—— 1991.

Second Supplement to the Red-Figures Vases of Apulia 1. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies Supplement 60/1. London: Institute for Classical Studies.

Vahtikari, V. 2014.

Tragedy Performances Outside Athens in the Late Fifth and Fourth Centuries BC.Papers and Monographs of the Finnish Institute at Athens 20. Helsinki: Suomen Ateenan-Instituut in säätiö.

Walsh, D. 2009.

Distorted Ideals in Greek Vase-Painting. The World of Mythological Burlesque.Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press.

Webster, T. B. L. 1948.

“South Italian Vases and Attic Drama.”Classical Quarterly42: 15–27.—— 1953–1954.

“Attic Comic Costume: A Reexamination.”Aρχαιoλoγική Eφημερíς: 192–201.—— 1960.