DELIAN ACCOUNTABILITY AND THE COST OF WRITING MATERIALS*

Irene Berti PH Heidelberg

Larger sanctuaries such as the Delian sanctuary of Apollo had a fully developed economy, huge incomes, and enormous costs of maintenance and organization.1On the Delian economy, see Reger 1994; Chankowski-Sablé 1997a; Chankowski 2012; Migeotte 2013. On the Delian administration, see Chankowski-Sablé 1997b; Chankowski 2008 and 2019, 9–66(both with previous bibliography).Alone for celebrating festivities, for example, vast sums were spent every year on the sacrifice of hundreds of cows, the accommodation and transportation of thetheoroi, the embellishment of the sanctuary, the decoration of the sacrificial animals, and the distribution of different honors.2See, for instance, the accounts of the Athenian amphictyons of Delos, 377–373 BC (Rhodes and Osborne 2003, no. 28).

To keep track of all the expenses, incomes, and loans required a sophisticated administrative system. The Athenian amphictyons and thehieropoioicompiled detailed accounts of all financial transactions, as well as inventories of the precious items stored in the sanctuary, in the process using a large number of different writing materials.3On Delian bookkeeping, see, especially, Chankowski 2013 and 2020. Contrary to the recent tendencies among epigraphists to consider the account stelae as (to various degrees) predominantly,partially or even purely symbolic (Epstein 2013, esp. 128 and 132; Faraguna 2013, esp. 166–167;concerning inventories: Linders 1988; see also Vial 1984, 220–222), I follow the approach that these inscriptions have a primarily practical nature. This approach has been recently defended by Véronique Chankowski, with excellent arguments reaffirming – without denying a certain secondary symbolic component – the function of the inscriptions as a “grand livre de comptabilité” (Chankowski 2013,esp. 919–920, 925, and 947–949. See also ead. 2019, 42–45 and 65–66; 2020, 68–69 and 71).

The majority of these documents, inscribed on perishable materials, are lost today, but have left indirect traces in the accounts engraved in stone, where many other writing materials such as tablets and (less frequently) papyri are mentioned,while recounting the details of accounting.

In this paper, I will attempt to answer the following questions: What was the relationship between the documents on perishable material and the stone stelae?How much did it cost to publish an inscription on stone? How common was the use of papyrus in the Hellenistic archival praxis of Delos? And finally, how much did it cost to keep a written record of the accounts?

Writing on stone

In Delos, between the fourth and second century BC, the sanctuary regularly inscribed giant stone stelae, on which inventories and accounts of general annual expenses were listed. These public stelae, which were commissioned and paid for by the sanctuary, had a rather curious production process, which shows important parallels to other large sanctuaries, such as those of Delphi and Epidauros.4On the different production strategies in Athens, Kos, and in the great panhellenic sanctuaries, see Berti 2013.

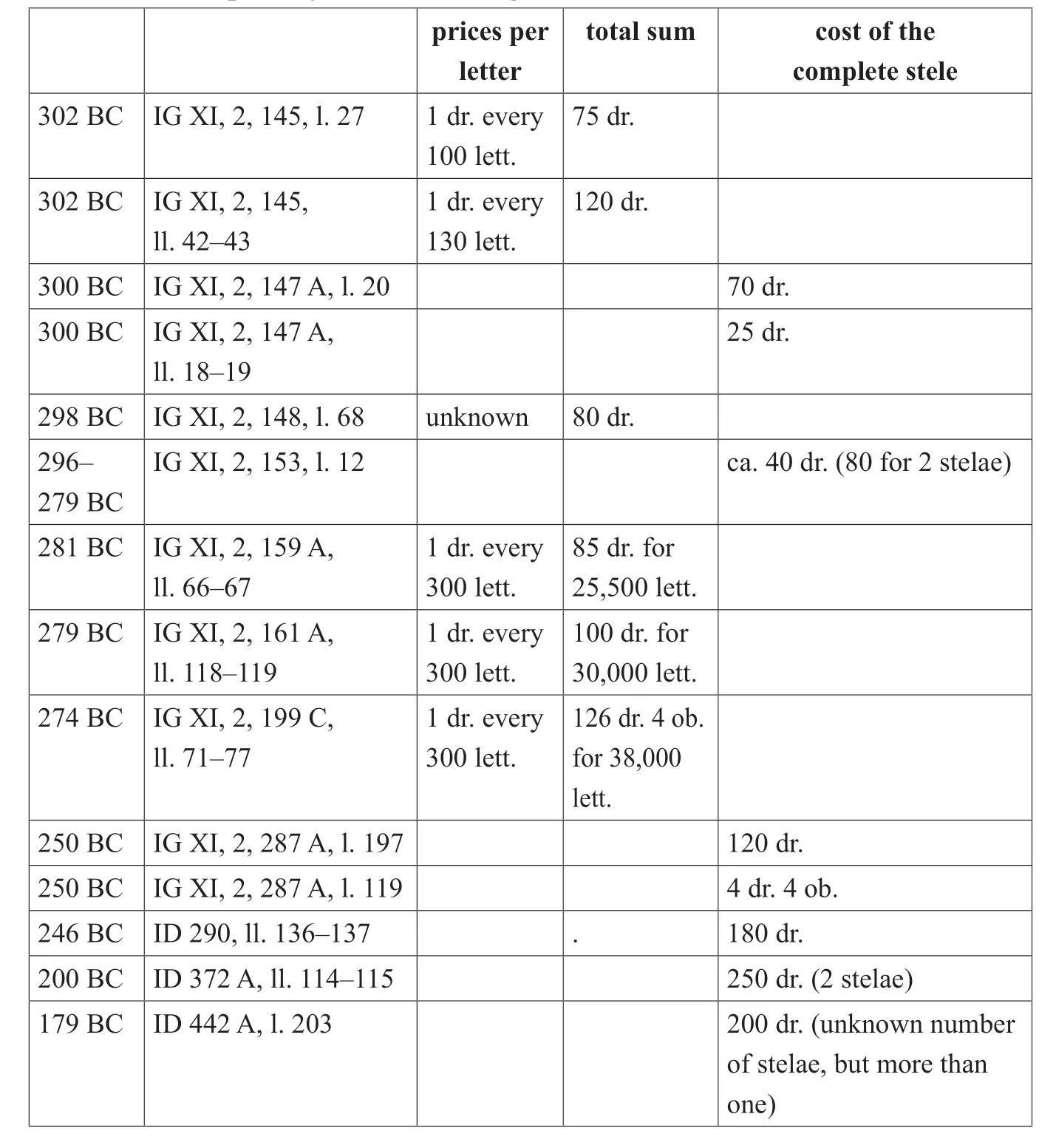

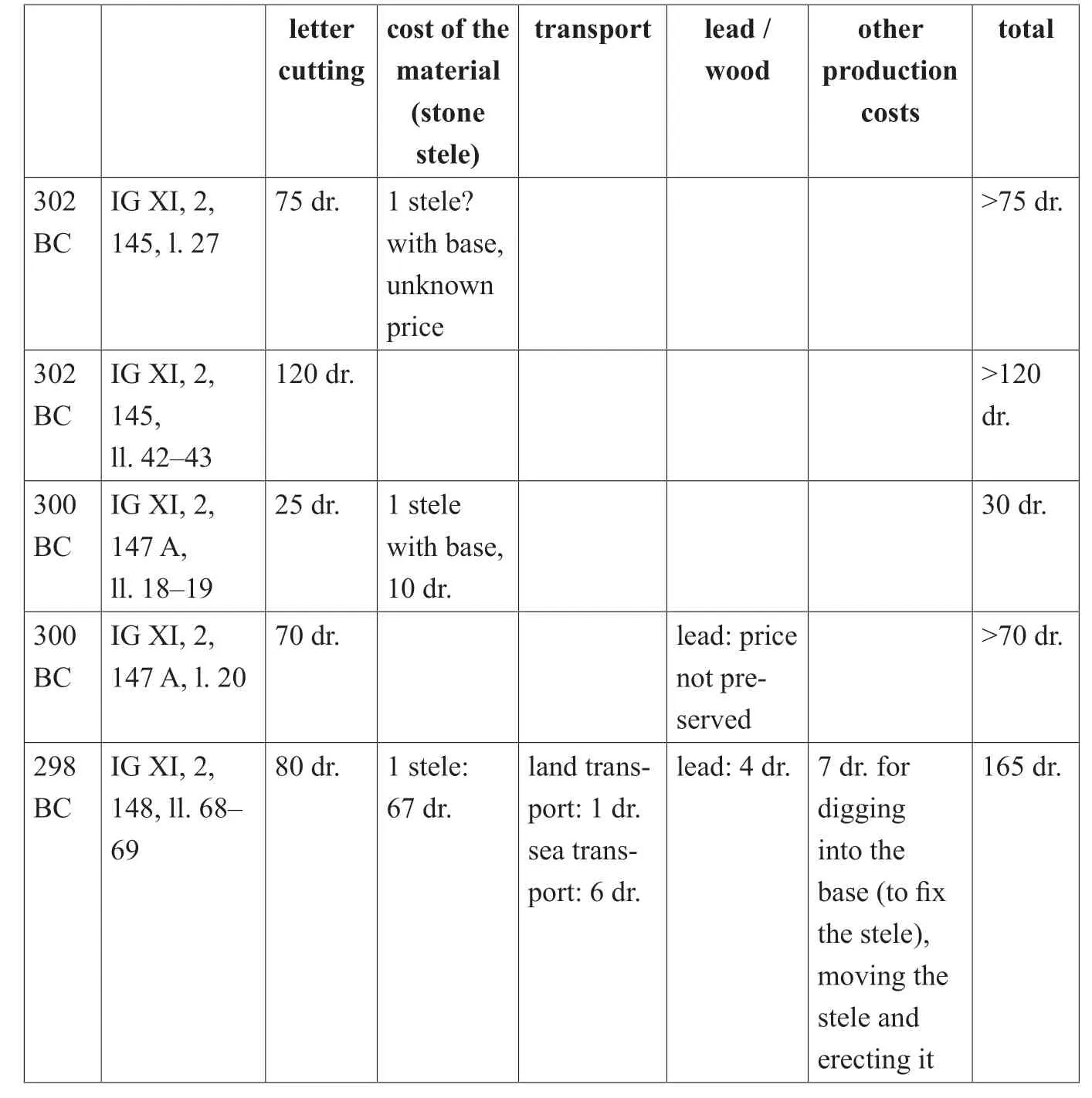

The stele was usually purchased from a supplier of rough material, probably directly at the quarry. It was then transported and inscribed “in loco.” The lettercutter was paid according to the number of letters cut, and all the expenses,from the purchase to the cutting and transport of the stone, were consequently mentioned separately in the accounts. For example, in the well-preserved account of thehieropoioifrom the year 279 BC, a large stele was purchased from Philonides for the price of 25 dr. A certain Deinomenes had cut the letters of the texts (30,000 characters) and had been paid 1 dr. for every 300 letters, thus earning the considerable sum of 100 drachmas for his work. Furthermore, the accounts register the costs of transport and of the erection of the stele, as well as the cost of the other materials necessary to fix the stone, such as lead and wood.5IG XI, 2, 161 A, ll. 117–119 (279 BC): στήλη παρὰ Φιλωνίδoυ ·ΔΔ· παραγαγoῦσι τὴν στήληνἐκ τoῦ Ἀσκληπιείoυ καὶ εἰς τὸ ἱερὸν ἀνακoμίσασιν ·˫ΙΙΙ· γράψαντι τὴν στήλην Δεινoμέν<ει> τῆς δραχμῆς γράμματα τριακόσια, τὰ πάντα γράμματα τρισμύρια, μισθὸς δραχμαὶ ·Η· μόλυβδoς ··ξύλα ·˫· τoῖς στήσασι τὴν στήλην ·˫˫ΙΙΙ· : / “a stele, bought from Philonides, 25 dr. To the (workers)who transported the stele from the Asklepieion and took it up to the sanctuary 1 dr. and 3 ob. To Deinomenes, for inscribing the stele, 1 dr. every 300 letters, for a total of 30,000 letters, as payment 100 dr.; (cost of) lead 5 dr.; wood 1 dr.; to the (workers) who erected the stele 2 dr. 3 ob.” See also tabs. 1 and 2.Summing up everything, we come to the conclusion that a stone stele with 30,000 letters cost around 135 drachmas.6However, we do not know how long it took for the letter-cutter to finish his work. On prices for letter-cutting generally, see Berti 2013, and for Delos in particular, see Chankowski 2013, 920–925.

Deinomenes, the letter-cutter, was a specialized artisan: He is previously mentioned in an inscription from the year 300 BC, where he was paid 70 dr. to inscribe a stele (the exact number of characters is unknown),7IG XI, 2, 147 A, l. 20.and in 281 BC,when he cut 25,500 letters for a payment of 85 dr., which confirms the price of 1 dr. for every 300 letters.8IG XI, 2, 159 A, ll. 66–67: γράψαντι τὰς στήλας Δεινoμένει, γράμματα τριακόσια τῆς δραχμῆς· τὰπά[ντ]α γράμματα δισμ[ύρια πεντακισχίλια πεντακόσια· ὁ πᾶ]ς μισθὸς δραχμαὶ ·ΔΔΔ· στήσαντι τὰς στήλας ·˫ΙΙ· μόλυβδoς ˫˫ ξύλα ·˫· : / “To Deinomenes, for inscribing the stelae at the price of 1 dr. every 300 letters, for a total of 25,000 characters. As payment 85 dr. To set up the stelae 1 dr.2 ob.; lead 2 dr.; wood: 1 dr. … .” See also Prêtre 2002, 85. On Deinomenes’ career, see also Feyel 2006, DÉL 128.

The price for letter-cutting of 1 dr. for every 300 letters paid to Deinomenes in 281 and 279 BC is also confirmed by an inscription from the year 274 BC.9IG XI, 2, 199 C, ll. 71–77: [τ]ῶι γράψαντι τ̣ῆ̣ς̣ [στή]λης γράμματα μιᾶς δραχμῆς HHH ὁ πᾶς μισθὸς γραμμάτων ΜΜΜΧΧΧ δραχμαὶ ΗΔΔ[˫ΙΙΙΙ]: / “for inscribing the stele at the price of 1 dr. for every 300 letters; the payment for the total of the 38,000 letters inscribed is 126 dr. 4 ob.”An older account, dated to 302 BC, shows that the price had been higher in the past:a certain Hermodikos was paid 1 dr. for every 130 letters;10IG XI, 2, 145, ll. 42–43. [γ]ράψαντι Ἑρμoδίκωι τῆς δραχμῆς ἑκατὸν τριάκoντα μισθὸς :ΗΔΔ:.in the same year, the same Hermodikos had cut letters for an even higher price (1 dr. for every 100 letters); this was most probably for a more elegant inscription, which took longer to be finished and required more skill and effort in terms of style and layout.11IG XI, 2, 145, l. 27 γράψαντι Ἑρμoδίκωι τῆς δραχμῆς ·Η· μισθὸς ΔΔ; Feyel 2006, DÉL 190. A similar case is attested in Delphi, where Deinomachos seems to generally expect two different rates:4 ob. every 100 letters for a quick writing style without embellishments; and 1 dr. every 100 letters for a more refined style (Feyel 2006, D 29; CID II, p. 167).

Analyzing the epigraphic evidence concerning the laborers employed on the construction sites of the great sanctuaries, Christophe Feyel concludes that in general the level of specialization of stonemasons and sculptors was low. Lettercutters, stone-cutters, and sculptors could work in many different jobs on these large building sites.12Feyel 2006, 377–378; 2007, 81.At Delos, for instance, the aforementioned Hermodikos worked as letter-cutter in the years 302 and 300 BC, but in one case he not only cut the letters, but also supplied and prepared the stone himself.13Ibid., DÉL 190. This seems to be a rather isolated case: at Delos, marble suppliers, stone masons,and letter-cutters were usually different individuals. See tab. 2 for details of the prices: the costs of manufacturing and preparation of the stelae are sometimes mentioned separately, sometimes together with the transport costs, and sometimes not mentioned at all, as they were probably included in the price of the stone.

Again at Delos, two letter-cutters (Deinomenes and Neogenes) also served as painters. This should not surprise us, since inscriptions, once cut, had to be rubricated; in 300, 281, and 279 BC Deinomenes worked as a letter-cutter, but in 279 BC he also painted the statue of Dionysos.14Ibid., DÉL 128.Neogenes inscribed some stelae again in 250 and 246 BC, but on several occasions he also made some encaustic paintings in the temple of Apollo.15Ibid., DÉL 371. An extreme case of a polyvalent artisan is that of Aristaios, employed on the building site of Epidauros and paid for letter-cutting, posing roof tiles, supplying tar, painting doors,cleaning the roof of a building, transporting wood, and various different kinds of restorations and small construction works (ibid., ÉPI 31; Mulliez 1998, 818).

A comparison with the epigraphic production of Delphi shows that lettercutters working in sanctuaries could occasionally be extremely specialized artisans: the career as letter-cutter of a certain Deinomachos can be followed(thanks to the extant accounts) across a period of fifteen years: from 337 until 322 BC, Deinomachos apparently did not work in any job other than lettercutting, at least at the sanctuary.16Feyel 2006, D 29. On the degree which the letter-cutters in Delphi were specialists, see Mulliez 1998, 815–830, esp. 817–819.As far as we know, he was a local worker who was active only in Delphi, and thus not one of the itinerant artisans usually employed by great sanctuaries, attested to since Homeric times.17Feyel 2006, 348–368.At Epidauros as well, some artisans seem likewise to have been more specialized than others;a certain Stasimenes, for instance, seems to have worked only to inscribe stones,and was paid, as was usual in these cases, according to the number of letters he had cut.18Ibid., ÉPI 279.

The style of cutting and the length of the inscription determined the time necessary to finish a stele. Different cutting styles took different times;monumental writing and utilitarian writing differ much in this regard, since they suppose different production times.19On the employment of different technologies and the different efforts required, see Helly 1979,63–89.The example of Hermodikos, the Delian letter-cutter who proposed two different rates for two different styles of inscriptions, shows that the letter-cutters were fully aware of the differences in the production process and considered them in their offer.20Feyel 2006, D 29.

Papyrus: chartai and chartia in the Delian accounts

Of course, stone was not the only writing material used by ancient administrations in accounting. On the contrary, it must have been rather the exception; the majority of “everyday” record keeping was done on perishable material, like papyrus or wood. As Véronique Chankowski recently demonstrated, perishable materials were widely used by the Delian administration not only for the drafts,but also for archival use, for instance, for keeping the monthly accounts.21Chankowski 2013, 926–929; 2020.

While it has been taken for granted that papyrus was the preferred writing material, we must consider that throughout antiquity people will have written on a large variety of materials, including parchment, ostraca, lead, and wooden tablets, particularly outside Egypt, where papyrus was not a local product.22On the different writing materials, see Bülow-Jacobsen 2009 with Plin. NH 13.21, who lists palm leaves, the bark of certain trees, sheets of lead, linen cloth, and tablets of wax. That the use of papyrus outside Egypt is later than Alexander the Great, as stated by Pliny, is obviously incorrect, but one can easily imagine that after Alexander’s conquests, papyrus might have been more widely used outside the territories of the former Persian Empire. On writing materials used to write private and public letters, see Sarri 2018, especially 17; 53–56, 72–77 (lead and papyrus).The unspecific terminology used for documents, which are usually assumed to have been prepared on papyrus, makes this issue even more complicated.

In the literary and epigraphic sources, papyrus as a writing material is generally called βιβλίoν, a term that can also simply mean a document, without implying a specific material; it is also referred to as βίβλoς, which can designate a roll of papyrus as well as the raw material. In epigraphic sources, the termchartes(χάρτης) is frequently attested, more commonly in the pluralchartai(χάρται);in the Delian accounts the diminutivechartion(χαρτίoν) orchartia(χαρτία)in the plural is also frequently found. We thus have to ask whether there was a difference between these two writing media, and if so, what was it?

It is not easy to define what achartesis: essentially, although usually translated as such, we are not even sure that it was (always) papyrus. The word can be used to identify a thin sheet made out of any material, for instance, a sheet of lead,like the one used fordefixiones.23LSJ, s.v. chartes. Thanks go to Kai Ruffing for the inspiring discussion on this subject.However, the use of the Latin termchartato designate documents on papyrus or parchment, the medieval use of the same word to indicate the “new” paper made out of rags, and the development of the Italiancartafor paper certainly suggest that the principal meaning of the word,at least since late Hellenistic times, was that of papyrus.24Capasso 1995, 29–30; TLL, s.v. charta. On the use of “paper” in medieval Europe, see Meyer and Sauer 2015.Nevertheless, it is far from certain that the meaning ofcharteswas already that of “papyrus roll” in the fifth century BC, as Napthali Lewis has suggested.25Lewis 1974, 71–78. On this subject, see Berti forthcoming.

In the Delian accounts,chartes/chartaiandchartion/chartiaare both frequently mentioned as writing materials, although not as frequently as the wooden writing tablets, which seem to have played a more important role in record keeping.

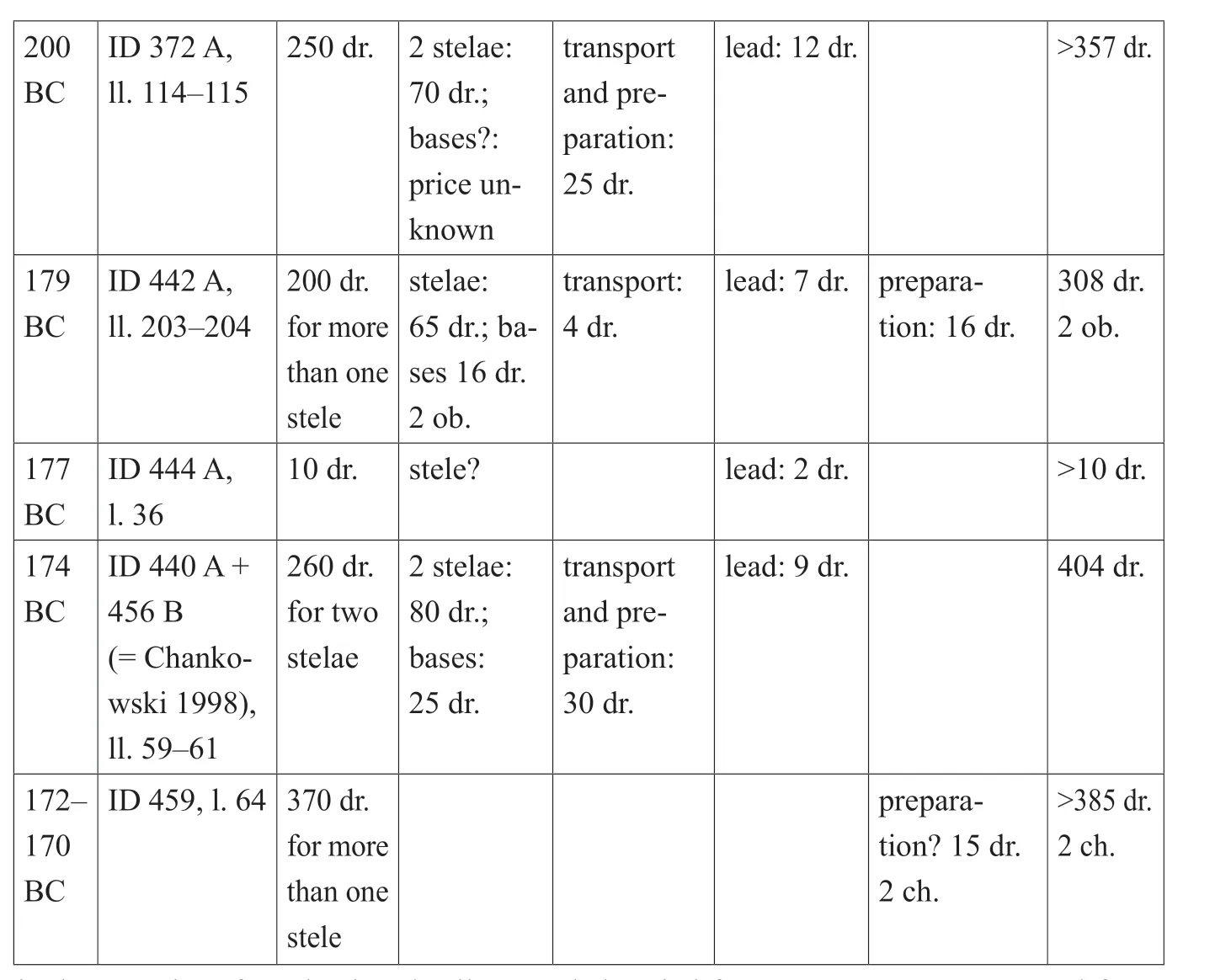

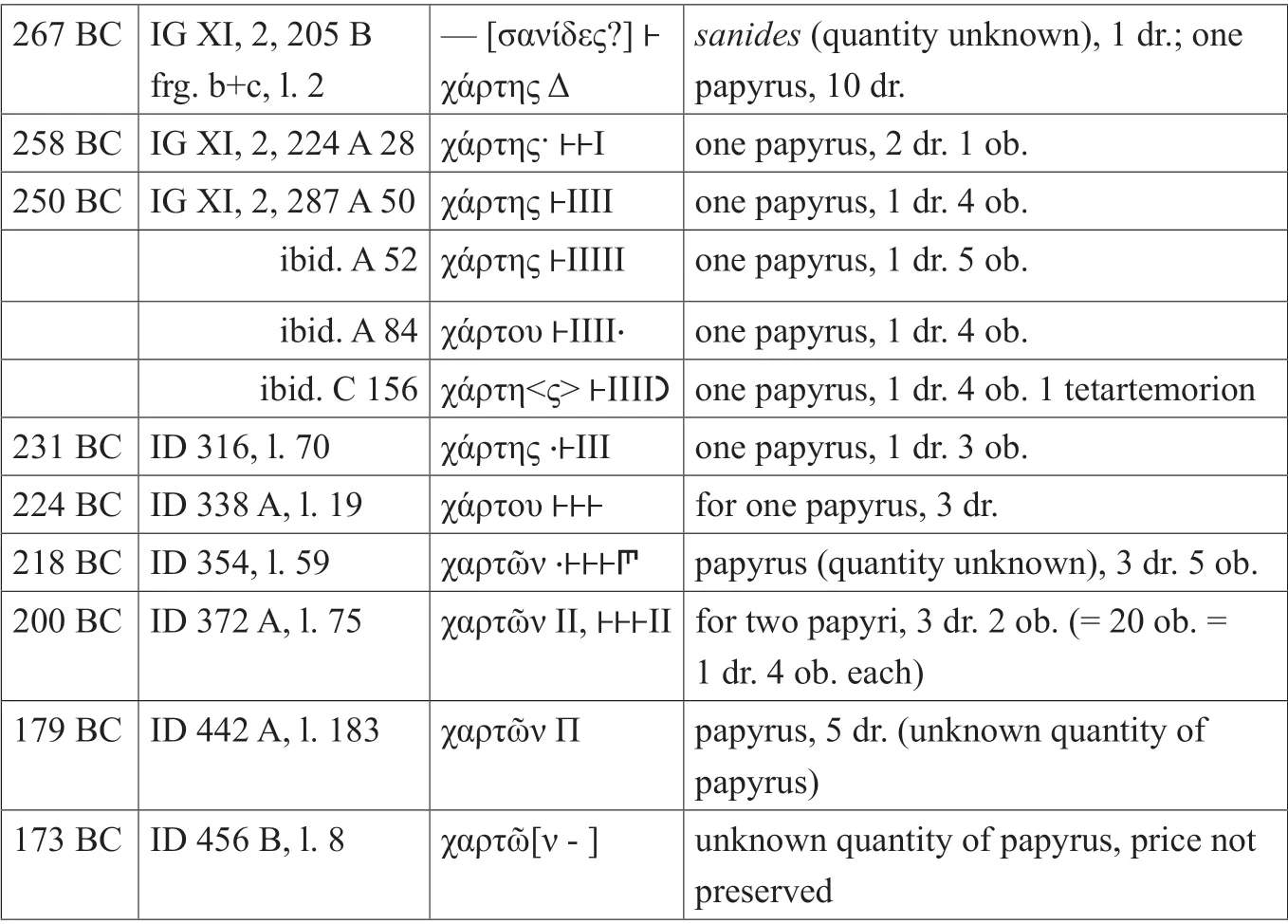

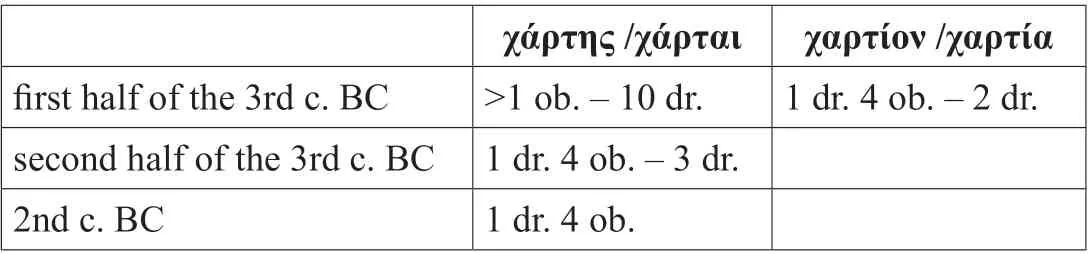

The first attestations can be dated to the beginning of the 3rd century BC. In 296 BC achartesappears to have cost only 1 or more ob. (but less than 6).26IG XI, 2, 154, l. 24 (296 BC): χάρτης̣ I[․․․․]OΛΛI. For an overview of the prices of papyrus, see tab. 3.This price is confirmed a few lines below, where an unspecified quantity ofbibliais purchased for only 1 dr.27IG XI, 2, 154, l. 34; see Glotz 1929, 6. The biblia mentioned in this account of expenses seem to be“books,” more than documents; the term biblion does not seem to have this administrative meaning in Delos.This is a rather low price, but since the inscription is difficult to read, we should take this with caution.

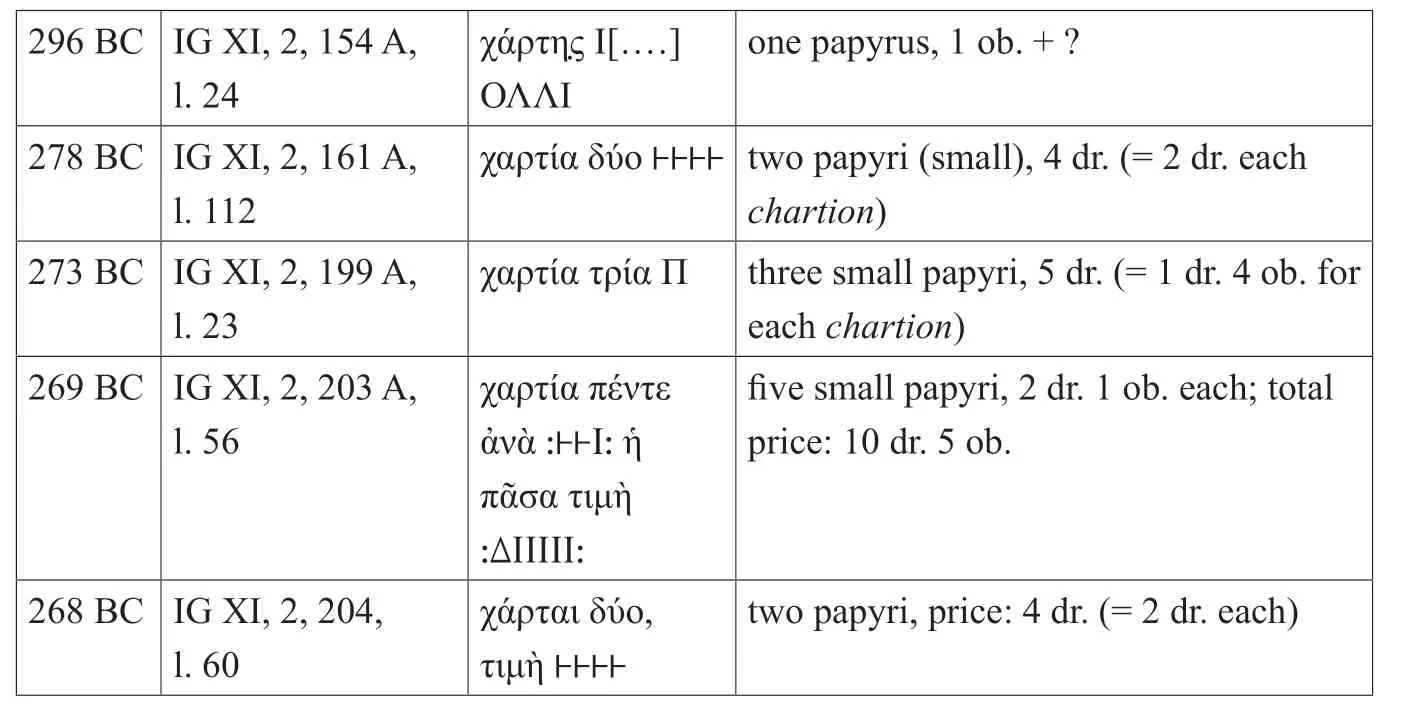

Just a few years later, between 278–269 BC, papyrus seems to have been much more expensive: twochartiacost around 2 dr. per “unit.”28IG XI, 2, 161, l. 112 (278 BC): χαρτία δύo ˫˫˫˫ / “Two chartia (small), 4 dr. (= 2 dr. each chartion);” IG XI, 2, 199, l. 23 (273 BC): χαρτία τρία Π / “Three chartia, five dr. (= 1 dr. 4 ob. each chartion);” IG XI, 2, 203, l. 56 (269 BC): χαρτία πέντε ἀνὰ :˫˫Ι: ἡ πᾶσα τιμὴ :ΔΙΙΙΙΙ: / “Five chartia,for 2 dr. 1 ob. each; total price 10 dr. 5 ob.”This difference in price is even more evident if we consider the use ofchartioninstead ofchartesas deliberate, and not as a synonym; achartionis presumably smaller than achartes, meaning that a smaller quantity of writing material was more expensive than a larger quantity some years earlier. In the account of 268 BC, a bigger “unit”(chartes) again costs 2 dr.29IG XI, 2, 204, l. 60 (268 BC): χάρται δύo, τιμὴ ˫˫˫˫ / “Two chartia, price: 4 dr. (= 2 dr. each).”See also IG XI, 2, 224, l. 28 (258 BC): χάρτης· ˫˫Ι:·/ “One papyrus, 2 dr. 1 ob.”

After 258 BC the prices appear to fall, as achartescosts only 1 dr. and 3 or 4 ob.30IG XI, 2, 287 (250 BC), l. 50: χάρτης ˫ΙΙΙΙ / “One papyrus, 1 dr. 4 ob.;” l. 52: χάρτης ˫ΙΙΙΙΙ· / “One papyrus, 1 dr. 5 ob.;” l. 84: χάρτoυ ˫ΙΙΙΙ· / “One papyrus, 1 dr. 4 ob.;” ID 316 (231 BC), l. 70: χάρτης·˫ΙΙΙ· / “One papyrus, 1 dr. 3 ob.”After 220 BC, the frequent use of the plural χαρτῶν likely implies the purchase of larger quantities and an increased use, but here caution is again necessary as the accounts of this period seldom record the exact quantity of the material purchased.31ID 354 (218 BC), l. 59: χαρτῶν · ˫˫˫ […] / “Papyrus (quantity unknown), 3 dr.+;” ID 372 (200 BC),l. 75: χαρτῶν ΙΙ, ˫˫˫ΙΙ / “For two papyrus, 3 dr. 2 ob. (= 20 ob. = 1 dr. 4 ob. each);” ID 442 (179 BC),l. 183: χαρτῶν Π / “Papyrus, 5 dr. (unknown quantity of papyrus).”On the whole, prices in Delos seem to have been rather stable until the end of the 3rd century BC. From the second century onwards, we have only two records: one mention of “some papyrus” for 5 dr. in the long and well published stele of the year 179 BC,32ID 442, l. 182: χαρτῶν .For commentary, see Prêtre 2002.and a mention of an unknown quantity and unknown amount a few years later.33ID 456, l. 8 (173 BC).

How widespread was the use of papyrus in Hellenistic Delos? Although papyrus does not survive in Greece under normal climatic conditions, we nevertheless have some traces of its use in the clay seal impressions that were used to seal the rolls, which are sometimes preserved.34Approximately 2,500 Hellenistic seal impressions of a public nature have been found in “building A” in Gitani (Thesprotia). Most of these still have the slit through which the cord that tied the roll was passed; occasionally, traces of papyrus have been discovered on the back of the seal impression(on the Thesprotian seals: Preka-Alexandri 1989 and 1996; see also ead. 1999 and Coqueugniot 2013,104–105). In Pella, a public archive was discovered in a building excavated at the southwest corner of the Agora, which preserved more than one hundred sealings of documents, fragments of styloi, and clay used for the sealing of documents (SEG 45, 784; Coqueugniot 2013, 121–122). The seals are dated to the 2nd to 1st century BC. See also ibid., 69–150 for similar examples.In Delos, a private house(“Maison des sceaux”) in the living area of Skardhana has preserved a huge quantity (16,000) of clay seals, dated between 166 and 69 BC.35SEG 43, 521; SEG 38, 772. See also Coqueugniot 2013, 93–96.The owner of the house is unknown, but the scarcity of official seals found prove that the(now lost) papyrus archive belonged to a private person involved in commercial transactions, likely a banker (or a rich merchant), and would have mainly consisted of contracts. Marie-Françoise Boussac suggests a semi-public role for the owner, who was, aside from his main activity, “un dépositaire à la fois des affaires d’autrui et de siennes propres” (syngraphophylax).36Boussac 1993, 683. A papyrus roll containing an honorary decree (but in form and appearance probably similar to the Delian lost documents) is mentioned already in IG II2 1, l. 61 (403/402 BC).The term used here to identify the document is βιβλίoν, which is attested only once in the Delian accounts, when an unspecified quantity of biblia seems to have cost 1 dr. (IG XI, 2, 154, l. 34; see also Glotz 1929, 6; see above with n. 27).

Although the archive was not public, it demonstrates that documents written on papyrus were not uncommon in Hellenistic Delos, at least since the middle of the second century BC. We can thus be fairly sure thatchartesdoes indeed refer to papyrus in the Delian inscriptions, but we still know nothing about the form and dimensions of this material in the accounting and recording practices. Doeschartesidentify a roll, or just a sheet? What is the relationship between achartes,which appears to be the “standard unit” in the Delian accounts, and its diminutivechartion?

As demonstrated by Lewis, and followed by Mario Capasso,chartescan be interpreted as a “roll,” especially since the Hellenistic age;37Lewis 1974, 71–72; Capasso 1995, 21–30. Capasso allows for certain exceptions, stating at ibid.,28–29 that chartes can also have the generic meaning of “carta scritta.”however, most of his arguments are either deductions based on later evidence or not really convincing,as the same evidence could be equally easily applied to demonstrate thatchartesmeant “sheet.” Chankowski interpretschartesin the Delian accounts as “feuilles de papyrus” and considers them as drafts, used by thehieropoioito make their preliminary calculations.38Chankowski 2013, 929–930; 2019, 42. In a previous article I also considered both chartai and chartiai as “sheets of paper” (Berti 2019).In her interpretation, papyrus plays no “official”role at all in the record-keeping of the Delianhieropoioi; this role she attributes instead to thedeltoi.39Chankowski 2013, 926–928; 2020, 66. See also below.

Although it is commonly agreed that papyrus left the factories in standard rolls of 20 sheets (for an average total length of 340 cm), the traders through whom it reached the customers could cut or make up rolls of any length desired by pasting together (or cutting) rolls, or sections of them.40Skeat 1982, 170–172. On papyrus as a writing material, see Ast et al. 2015.Papyrus thus also circulated as single sheets, as we know for certain from private letters.41Ibid., 312–313 and 317–319.The height of a sheet in the Greco-Roman time seems to have been around 30 cm on average.42Ibid., 308.This could perhaps correspond to the material calledchartionin the Delian accounts,which should consequently be translated as a “papyrus sheet.” What aboutchartes/chartai? Should we imagine this to be a roll? The private archive of Skardhana seems to suggest that rolls were used in Delos during the second half of the second century BC, so it is not improbable thatchartesmeans more than just one sheet. Still, we do not know the length of such rolls. Hence the question:Did they always have the same length?

We know that ancient Egyptian papyrus rolls could be as long as 40 meters,but most of these very long rolls are copies of the Book of the Dead, made to be buried with the deceased, not to be read out publicly or for any other practical use. Greek papyrus rolls seem to have been no longer than 10–11 meters (and were probably often shorter), however only a few complete Greek rolls have survived until now, so the original length is mostly a hypothetical reconstruction based on a counting of the letters and lines.43Bülow-Jacobsen 2009, 21.

Generally, it seems wiser to leave the question of “roll” or “sheet” in the Delian accounts open, since we have no indication at all about the dimensions of the material. The seemingly interchangeable use ofchartesandchartionin the accounts does not make things easier. Probably,chartesis just a general term meaning both the roll and the sheet, approximately equivalent to our “paper,”without any reference to the form or quantity of papyrus (such details were obviously irrelevant in the context of the accounts and therefore not mentioned).44See also Lewis 1974, 77.

Nonetheless, the consequences of accepting one hypothesis or the other are considerable, since the quantitative difference between a sheet and a roll is significant. If we accept that, following Lewis, the evidence can be interpreted as meaning thatcharteswas used to designate a roll, then the price of papyrus seems to have been quite low, even outside Egypt.

In addition to this, Pliny the Elder – our principal source on the production of papyrus – lists seven qualities of papyrus being produced at his time,45Plin. NH 13.74–82.which surely had different prices. When purchases of papyrus are recorded in accounts,we are never told exactly how much material is really bought (because we do not know the size of the writing medium) and also have no information about the quality of the material (quality matters on stone, so this is likely the case with papyrus, too!). Moreover, papyrus, being imported from the other side of the Mediterranean, was probably subject to the fluctuations characteristic of the international markets and its price dependent on changing political influences in the Kyklades. At this point, however, we should consider the possibility that the sanctuary regularly bought large quantities of goods and stored them, or that the imported goods were purchased by the sanctuary from local retailers.The storage of material for short periods could thus have influenced price formation. Chankowski argues that since the second half of the third century BC, the administration of the sanctuary stabilized the organization of supplies, a fact which consequently lowered prices. This tendency towards stable low prices is clearly visible in the trend of pitch and oil prices, and is the result of the regularity of their supply and storage, which disconnected the prices from seasonal fluctuations due to the differences between winter and summer navigation.46Chankowski 2019, 255 and 274.It is possible that this pattern also applies to papyrus; although the scarcity of evidence encourages caution, this could help to explain why papyrus – which is usually bought more than once a year and during different seasons – has a stable price, which appears not to have been influenced by seasonal transportation fees.

Generally, it seems that the administration preferred to buy larger amounts of papyrus; while the purchase ofchartaiis frequently attested in the third century BC,chartiaare mentioned only three times during this period.47IG XI, 2, 161, l. 112 (278 BC); IG XI, 2, 199, l. 23 (273 BC); IG XI, 2, 203, l. 56 (269 BC).A puzzling circumstance, which needs further research, is the fact that achartiondoes not seem to be cheaper than achartes; on the contrary, it costs the same or even more. Exceptional prices, like the 10 dr. paid for 1chartesin 267 BC,48IG XI, 2, 205, b+c, l. 2: χάρτης Δ.are surely due to some especially high quality papyrus or to an extra-long roll.

How do these prices fit within the general market trend? The lack of sources on the import/export of papyrus from Ptolemaic Egypt to Greece makes reconstructing the market for papyrus outside Egypt particularly difficult. While Egyptian Hellenistic papyri are rich in details about the provenience of imported goods, they seldom mention exports.49Huss 2012, 31–32.

In general, papyrus prices in Greece seem to have fallen after Alexander’s conquest of Egypt, which opened up the market; in the fourth century BC,papyrus prices were lower than in the fifth century BC, but they tended to rise again during the early part of the third century BC.50Glotz 1929, 7–8.This is, in Gustave Glotz’s hypothesis, due to the introduction of the Ptolemaic monopoly over production,and the resulting absence of competitors in the market, two factors which could have helped to keep prices high. Gary Reger connected the fluctuation of the price of papyrus in Delos with military demand (papyrus, like pitch, is a strategic good, much used in naval engineering, e.g., for ropes and lines), but he does not consider the different qualities of papyrus sold on the market.51Reger 1997, 60–61.

During the 3rd century BC, prices of papyrus in Egypt were generally lower than in Delos (between 3 ob. and 1 dr. and a few oboloi in Egypt / generally between 1 and 2 dr., and occasionally up to 10 dr. in Delos), but this should come as no surprise if we consider that papyrus had a long way to travel before it arrived in Delos and was – being fragile and sensitive to water – likely difficult to transport.52For the prices in Delos, see tabs. 3 and 4.The difference in prices is even more remarkable if we takechartesto be a “sheet” instead of a roll. Lewis considers the difference between the prices in Egypt and the prices in Greece as being too great, and uses this as an argument to suggest that, as in Egypt, papyrus circulated in Greece only in the form of rolls.53Lewis 1974, 76: “The prices recorded for a χάρτης at Delos range from 1 drachma 3 obols to 2 drachmas 1 obol. Allowing for the cost of export and import these prices accord well with the range of 3½ obols to 1 drachma 1 obol found in Ptolemaic Egypt. Were χάρτης a mere sheet of paper in Delos,the discrepancies in price would be astronomical.” On papyrus prices, see ibid., 129–134.The comparison of the prices forchartai/chartiawith those for wooden tablets seems to point in yet another direction, as we will see in the following section.54See my conclusions.

Wooden tablets

Aside from papyrus, the Delian accounts also very frequently mentionsanides,leukomata,deltoi, andpeteura.55On the terminology, see also Degni 1998, who analyzes tablets used as support for literature.Generally, on wooden tablets, see Lalou 1992; Jördens, Ott and Ast 2015; Berkes et al. 2015.These are wooden tablets, mostly whitened or waxed, which were used to record the accounts kept in the archive, or to write contracts to be handed over to the contractors; however, they could also be used as public boards destined for temporary exhibition, for the people or other political institutions.56Ostraca are never mentioned in the Delian accounts. Although in Egypt, where they were considered a surrogate for papyrus, potsherds and even flakes of limestone were widely used for everyday writing (private and public), they do not seem to have had the same importance outside Egypt, where just a few finds attest to a mainly private use (aside from the eponymous Athenian political use). Ostraca have the great advantage of being entirely free, but they are heavier than papyrus or wood, and due to their irregular form they are not easy to store or archive (and also difficult to write on). Beyond that, they are not suitable for long texts. See Bülow-Jacobsen 2009,14–17.Generally, these documents are to be considered supplementary to the stelae, and not as a substitute. In Delos, the stelae record the annual financial records, while the tablets report the monthly records. This is clearly stated in the account of the year 279/278 BC, where a whitened tablet(leukoma) was bought for three oboloi to display the monthly accounts in the agora.57IG XI, 2, 161 A, l. 89 (278 BC): τoῖς κατὰ μῆνα λόγoις ἐκτιθεμένoις εἰς τὴν ἀγoρὰν λεύκωμα ·ΙΙΙ.On this subject and on the difference in the accountability between monthly and yearly accounts, see Chankowski 2013, 927–928.While the annual accounts of thehieropoioiwere published on a stele,it seems that the monthly accounts were written on a more ephemeral material,which was displayed for a while, and then likely removed from public display when the new monthly account was to be published. Tablets could also be given to single contractors; while in this case the stele simply listed the contracts stipulated, the single tablets would likely have reported the details of each individual contract. This seems to be the case in the same, aforementioned stele from the year 279/278 BC, where 3 dr. were spent to prepare the tablets for the contracts (syngrapheis) and the account.58IG XI, 2, 161 A, l. 113–114 (278 BC): ταῖς συγγραφαῖς καὶ τῶι λόγωι λευκώματα λευκώσαντι ˫˫˫. /“to whitewash the leukomata for the contracts and the account, 3 dr.”Leukomatacould also be used to record security agreements (diengyeseis), as we know from a stele dated to the middle of the third century BC.59IG XI, 2, 287, ll. 43–44 (250 BC): λευκώματα εἰς διεγγυ[ήσεις] ˫Ι / “leukomata (quantity unknown)for the security-agreements.”Leukomatahad the advantage that they could be reused, after being whitened, many times.60On leukomata, see also Chankowski 2020, 65–66.

The prices forleukomatawere usually low. In a Delian account from the beginning of the third century BC, a whitened tablet (leukoma) costs 1 dr. 3 ob.,61IG XI, 2, 153 (297–279 BC), l. 12: λεύκωμα ˫ΙΙΙ·= 1 dr. 3 ob.while in an account of the middle of the third (265 BC), the cost is 2 dr. per tablet.62IG XI, 2, 219 (265 BC), l. 38: λεύ[κωμα ταῖς] συγγραφαῖς·˫˫ / “one leukoma for the contracts,2 dr.”In an account published a few years later, the tablets appear to be cheaper(1 dr. 1 ob., probably, for an unspecified quantity ofleukomata– but surely more than one); in the same account (l. 71), registered under the monthly purchases of Bouphronion a couple of months later, two tablets were bought for 3 dr. 2 ob.,and some additional money (1 dr. 4 ob.) was paid in order to whitewash them.63IG XI, 2, 287, ll. 43–44 (250 BC): λευκώματα εἰς διεγγυ[ήσεις] ˫Ι / “leukomata (quantity unknown) for the security-agreements 1 dr. 1 ob.;” l. 71: Ἀνδρoκράτει λευκ<ω>μάτων δύo ὥστε ταῖς συγγραφαῖς ˫˫˫ΙΙ· Noυμάκωι λευκώσαντι ˫ΙΙΙΙ / “For Androkrates, for two leukomata to write the contracts, 3 dr. 2 ob.” (= 1 dr. 4 ob. each leukoma); for Noumakos, to whitewash them.” For a general overview of the prices for tablets, see tab. 5.

Although the production of writing tablets needs almost no specialized technology, they do need to be prepared with white paint, and must also be assembled. In an account from the year 269 BC, a certain Deinomenes was paid 8 dr. for cutting, pasting, and whitewashingleukomata(it is not specified how many).64IG XI, 2, 203, l. 57 (269 BC): Δεινoμένει Λεωφάντoυ διαπρίσαντι καὶ κoλλήσνατι καὶ λευκώσαντι λευκώματα :Π˫˫˫: / “To Deinomenes, son of Leophantes, for cutting, pasting and whitewashing leukomata (quantity unknown): 8 dr.”Usually more tablets were assembled to form a booklet, like the one attested on red-figured vase-paintings and by the leaf-tablets of Vindolanda.65See, for instance, Munich, Antikensammlungen 2607 (https://www.avi.unibas.ch/DB/searchform.html?ID=5528); 2314 (http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/561DFABC-6039-41BD-B028-5A4352150F72); Bologna, Museo Civico Archeologico 376 (http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/7FB12302-D136-4D2D-ACDB-593F07496279); Metropolitan Museum 06.1021.167 (http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/9BF455A1-FBAF-4612-9B79-85A9D80AB113) (all accessed 17.04.2021). Examples of this kind of polyptycha have been also found at Herculaneum and in the Roman East. On this, see Bülow-Jacobsen 2009, 23; Sarri 2018, 79–84; Capasso 1992.

Sanidesare not frequently mentioned in the Delian accounts, and these appear to have been similar toleukomata. They also needed to be whitened and could be used to record the accounts (logos).66IG XI, 2, 199, l. 54 (273 BC): [λευκώσαν]τι τὴν σανίδα τῶι λόγωι ·˫ΙΙ·/ “to whitewash a sanis for the account, 1 dr. 2 ob.”The prices were also similar to those attested forleukomata, ranging from 3 ob. to 2 dr. (on average they cost ca. 1 dr.);also in this case, in addition to the purchase itself, one has to consider the extra money normally spent to whitewash the tablets. The termssanisandleukomamay have been synonyms.

Besideleukomataandsanides, the Delian accounts frequently mention the use of adeltos.Deltoiappear to have been in general more expensive thanleukomata,sanides, andpeteura, and were occasionally made of a special type of wood. While we are never told which sort of wood is used to makeleukomataorsanides, the accounts frequently mentiondeltoimade of cypress wood.

An account of the Delianhieropoioi, dated to the year 250 BC, highlights the relationship between the diverse writing materials; here, adeltosis written up from a stele, which should be considered the authoritative “original,” while the tablet is the copy (for the archive?).67IG XI, 2, 287, l. 197. See also Chankowski 2013, 926: “La formule employée par les hiéropes ne laisse pas de doute sur l’ordre des opérations, pour cet achat qui figure toujours quelques lignes après les dépenses pour la stèle de compte: ils font graver sur le δέλτoς les informations qui proviennent de la stèle.” See also ead. 2019, 39–40, arguing that deltoi were copies for the archive (see ibid., n. 126 for the possible location), and 2020, 65–67.The preparation and inscribing of thedeltosis relatively expensive but – of course – not comparable to the cutting of a stele. While the letter-cutter Neogenes was paid 120 dr. to inscribe the stele(Nεoγένει γράψαντι τὴν στήλην), to “make” thedeltos(δέλτoν πoήσαντι), the administration spent 3 dr., as well as 4 dr. more to write the contents of the stele on it (τῶι εἰς τὴν δέλτoν γράψαντι τὰ ἐκ τῆς στήλης).68IG XI, 2, 287 (250 BC), l. 197: Nεoγένει γράψαντι τὴν στήλην ΗΔΔ· δέλτoν πoήσαντι ˫˫˫· τῶι εἰς τὴν δέλτoν γράψαντι τὰ ἐκ τῆς στήλης ˫˫˫˫ / “To Neogenes, to inscribe the stele, 120 dr. To make a deltos 3 dr., to inscribe it from the stele, 4 dr.”Since no other tablet for the annual account is mentioned in this section at the end of the stele, it seems clear that the content of the stele was supposed to fit on onedeltos, which must have thus been of considerable size.

Adeltosusually cost 3 or 4 dr. in the records (which is more than the average price of papyrus),69See, for example, IG XI, 2, 148, l. 70; IG XI, 2, 154, l. 46; and tab. 4 for a comparison with the other media.although very high prices like 10 or even 16 dr. are attested.70ID 290 (246 BC), l. 137: δέλτoς Δ· τῶι γράψαντι τὴν δέλτ[oν - - - -] / “deltos, 10 dr, to inscribe it…;” IG XI, 2, 147 (300 BC), l. 14: δέλτoς ΔΠ˫ / “one deltos, 16 dr.”In an account from 200 BC, a tablet of cypress wood (δέλτoυ κυπαρισσίνης)costs 10 dr., and 15 more dr. were spent to inscribe it.71In ID 372 A (200 BC), l. 116.Even more expensive is adeltosof cypress wood bought and inscribed at the beginning of the second century BC.72ID 440 A (198–180 BC), l. 47: δέλτoυ κυπαρισσίνης ΔΠ· τῶι γράψαντι Δ̣Δ̣Π· / “a deltos of cypress wood 15 dr., 25 to inscribe it.”In these last two examples, the use of a valuable wood (cypress)suggests that the documents were probably written to be displayed in some way –not just to be placed in the archive.73Literary sources frequently mention boxwood (πυξίoν) as a material for the production of wooden tablets. This type of wood is very common in the Mediterranean area, and therefore not expensive(see Meiggs 1982, 282). On materials for wooden tablets, see Degni 1998, 66–68. The archaeological evidence confirms that local woods were generally preferred.

Peteuraappear to have had the same costs asleukomataandsanides(about 1 dr. per piece, certainly cheaper thandeltoi), and were probably very similar toleukomatawith regard to the form, use, and quality of the material. Also in this case, more money was usually spent to inscribe them.Peteurawere normally used for the registration of contracts or for recording security agreements (ταῖς διεγγυήσεσιν).74ID 316 (231 BC), ll. 70–71: [πέτευρoν ταῖς] διεγγυήσεσιν ·ΙΙΙ· / “a peteuron for the security agreements, 3 ob.;” ID 338 (224 BC), l. 19: πέτευρoν ταῖς διε[γ]γυήσεσιν ΙΙC· / “a peteuron for the security agreements, 2 ob. and a half;” ID 372 (200 BC), l. 75: πέτευρoν ταῖς διεγγυήσεσιν ˫ΙΙΙΙ /“a peteuron for the security agreements, 1 dr. 4 ob.;” l. 103: πέτευρoν τῆι ἱερᾶι συνγραφῆι καὶ ταῖς διεγγυήσεσιν τῶν τεμενῶν [˫]˫ΙΙ / “a peteuron for the sacred contract and the security agreements of the temenoi 2 dr. 2 ob.;” l. 116: πέτευρα τῶι λόγωι καὶ ταῖς συγγραφαῖς καὶ τ[εῖ] παραδόσει ˫ΙΙΙΙ·τῶι γράψαντι Δ̣[…] / “peteura for the account and the contracts and for the paradosis 1 dr. 4 ob.; to inscribe them 10 dr. +;” ID 440 (198–180 BC), ll. 3–4: πέτευρα καὶ τῶι γράψαντι [τὰς διε]γγυήσεις καὶ τὰς συγγραφὰς ΔΠ˫· / “peteura (quantity unknown) and to inscribe the security agreements and the contracts, 16 dr.;” ID 442 (179 BC), l. 200: πέτευρα ταῖς] δι[εγγ]υήσεσιν καὶ ταῖς συγγραφαῖς Π˫˫˫ / “peteura (quantity unknown) for the security agreements and the contracts, 8 dr.;” l. 204:[πέτευρα ταῖς π]αραδόσεσιν Π˫˫˫· καὶ τῶι γράψαντι Δ˫˫ / “peteura for the paradosis, 8 dr., to inscribe it, 12 dr.;” see also ID 354 (218 BC), l. 61.

In an account from the first half of the second century BC, somepeteurawere used to inscribe theparadosis, for a total cost of 10 dr. for the material, plus 14 dr. to write the text.75ID 459 (172 or 170 BC), l. 60: [πέτευρα ταῖς παραδόσεσιν] Δ· [τ]ῶι γράψαντι Δ˫˫˫˫ / “peteura for the paradosis, 10 dr., to inscribe it, 14 dr.” On the use of peteura, see also Chankowski 2019, 41 and 2020, 66.Unfortunately we do not know how many tablets were necessary – the quantity is not specified – but the generally attested low price of the single pieces and the high writing costs suggest at least 8–10 tablets. The high cost of inscribing is confirmed by the accounts of the years 200 BC (more than 10 dr.), 198–180 BC (16 dr.), and 179 BC (12 dr.).76ID 372, l. 116; ID 440, l. 34; ID 442, l. 204 (see also above, ns. 71–72).The mention of theparadosiscould help to explain the relationship between the stele and copies of the stele on wooden tablets. The handing over of the different funds and accounts from one administrative board to the next was a complex process, which implied not only recording but also checking (both on site and in the presence of council and magistrates) the jars containing the sums collected and stored in the temple,as well as reporting to the assembly on incomes and outlays, a process which could obviously not have been done using a stele. Instead, moveable copies from the accounts on stone would have been required.77The transmission of the sacred finances from one board of hieropoioi to the next is described in detail in Vial 1984, 217–227, esp. 225–226. See also Chankowski 2019, 46–47. To get an idea of how the paradosis was achieved technically and how many magistrates were involved, it is useful to compare the procedure of exetasmos recorded in the Athenian inventory of the Chalkotheke from the year 353/352 BC (IG II2 120).

In an account from 302 BC,peteuraappear to have had the same function ofdeltoiand were used to inscribe the account (τῶι λόγωι), but have definitely a more reasonable price: here, an unknown quantity of tablets cost just 2 dr. 3 ob.78IG XI, 2, 145 (302 BC), l. 44: πέτευρα τῶι λόγωι ·˫˫ΙΙΙ·/ “peteura (quantity unknown) for the account, 2 dr. 3 ob.”The similarity in the use is confirmed by an account from 296 BC, where adeltosand apeteuronwere bought together, both for writing the account (τῶι λόγωι);while apeteuroncost only 1 dr. 4 ob., thedeltoswas more expensive (3 dr. 4 ob.and a half).79IG XI, 2, 154 (296 BC), l. 46: πέτευρoν τῶι λόγωι· ˫ΙΙΙ· δέλτoς τῶι λόγωι· ˫˫˫ΙΙΙΙ̣C· / “a peteuron for the account, 1 dr. 3 ob.; a deltos for the account, 3 dr. 4 ob. and a half.”As with papyrus, the texts of the stelae do not inform us about the quality of the wood used forpeteura, although it was likely a cheaper and more common one than the cypress used fordeltoi.

What did the wooden tablets look like, and how large (or small) were they?To understand the relationship between the different writing materials and how they interacted with each other, this is an essential question. Unfortunately, it is also one without a certain answer. Extant Greek tablets from the Classical and Hellenistic period are very rare outside Egypt.

Bülow-Jacobsen distinguishes between wooden boards and wooden leaf tablets.80Bülow-Jacobsen 2009, 12–14.This last type is well known from Vindolanda in northern England,where many well-preserved exemplars have come to light. These are composed of very thin slices (1–2 mm, some even thinner) of alder or birch, with a surface of ca 16–20 cm by 6–9 cm, inscribed with ink.81See as an example T.Vindol. II 310 or P. Yadin 54. See also Sarri 2018, 83–84.When used for letters, the tablets were written in two columns parallel to the sides, then scored lightly in the middle and folded. If the text was an account, the texts on the slices were usually inscribed parallel to the ends, and then folded; if the text was long, several slices could be folded and tied together to form a “concertina book.”

In 1981, a salvage excavation at Daphni, in Attica, unearthed the grave of a musician (Tomb 2), together with a second grave that was probably part of the same family burial (Tomb 1). Both graves are dated to the second half of the fifth century BC. Tomb 2 contained not only the remains of musical instruments, but also a bundle of writing tablets, a papyrus roll, a writing case, a chisel, a bronze stylus, and a bronze ink pot.82The objects are exhibited at the Piraeus Museum (MΠ 7456; MΠ 7445; MΠ 7452–7455; MΠ 7449,MΠ 8517–8523; MΠ 7444; MΠ 7443). See Pöhlmann and West 2012; Karamanou 2016.

The tablets, small and rectangular in size, are in good condition, and part of the wax coating is still preserved. Three of them are of matching size, 10 x 5 x 0.3 cm,and no doubt they formed a set; they have holes on one of the sides, so that they could be tied together with a thong or rings to form a polyptychon. This is confirmed by the fact that on both faces of the three smaller tablets the central part of the surface is chiseled out to leave a writing area surrounded by a raised frame; this protected the written surfaces from rubbing against each other when the tablets were bound together. The writing area was plastered with a yellowishbrown wax.

The fourth tablet, which has been reconstructed from many fragments, is larger,has no holes, and has been arranged to be waxed on one face only. The different dimensions and the fact that the tablet was not designed to be written on both faces, indicate that it was not part of the polyptychon and was not fastened to the others. The wax on this tablet is a much more vivid red.83Pöhlmann and West 2012, 3.The preserved wax has enabled the discovery of some very small and carefully carved letters. Although this is not enough to reconstruct the text, it is nevertheless possible to make a hypothesis on the content (probably a poem),84On the content of papyrus and tablets and the musical and literary context, which can be reconstructed, see Pöhlmann and West 2012; Karamanou 2016.and to reconstruct the length of the text as well as the number of characters contained on one face. According to the reconstruction, one face contained around 14–17 lines, with 70–80 letters per line, which amounts to around 1,160 characters on each face.85Jördens, Ott and Ast 2015, 380.To inscribe the 30,000 characters of Philonides’ and Deinomenes’ stele (IG XI, 2, 161), one would have needed 13 double-faced tablets. It is possible that the dimensions of the tablets found in the tomb of the musician are smaller than usual; indeed,they seem to be very small when compared (by way of example) with the school tablets painted on a cup by the painter Douris at the beginning of the fifth century BC, which are much larger.86Berlin, Antikensammlung F2285. See also Jördens, Ott and Ast 2015, 380–381.Nevertheless, a brief glance into the survey of preserved documentary wooden tablets in Greek found in and outside Egypt shows that tablets of smaller size were not uncommon, especially for receipts,although larger ones are also attested.87See, for instance, TM 64463, from the fourth century AD, used to write a school text (30.5 x 17.5 cm);TM 64281 from the third century AD (30 x 13.5 cm), writing exercises; TM 15480, fourth century AD(13.7 x 30.5 cm); TM 65165, 6/7 AD, division table (30 x 18 cm); TM 108302, 500–900 AD, Psalm(8 x 30 cm). See Worp 2012, nos. 208, 224, 242, 362, and 372.In the Latin west, the average dimension of the Vindolanda tablets is something like that of a modern postcard.88Berkes et al. 2015, 386.

Conclusions

Every year, the Delian administration of the sanctuary spent between 150 and 450 dr. for the record-keeping of the accounts. Of this sum, on average ca. 200 dr.were spent each year for the publication of a stele. Although seemingly extremely high, our understanding of the relative importance of these costs is diminished when comparing them with the inordinately higher ordinary expenses incurred as a result of the normal activities of the sanctuary, such as the celebration of festivities.89The expenses for the Delia, for example, amounted to 4–6 talents every four years. See also Chankowski 2013, 924.

To keep a written record of the financial transactions, a wide range of different materials were used. While tablets are already attested in the fourth century BC,ifchartaiis papyrus, papyrus only appears in the accounts later, at the beginning of the third century BC. Generally, the Delian accounts do not give the impression that papyrus was either widely used or was particularly valued as a writing material for documents of the sanctuary, while the use of wooden tablets is certainly better attested. These could be of highly diverse types with varying prices, and their use is less generic than the unspecified use ofchartai. Tablets offer many advantages in the documentary praxis: they are a flexible writing medium, their prices range from a few ob. to more than 10 dr., and they could be used for a broad variety of needs.

The availability of the materials likely also played a role in the choice of the writing medium. Stone for the stelae may have been quarried locally in Delos,or it may have been imported from a short distance away (for instance, from Paros or Thasos, which were both rich in marble of high quality), while wood for the tablets was probably imported from the neighboring islands, as well as from northern Greece. Wood, like stone, was widely used in a huge sanctuary,and their importation of large quantities (with the obvious exception of precious woods) may have played a role in keeping the price low.90On the import of timber for construction, mentioned in the Delian accounts, see Meiggs 1982,441–457. Delos seems already in antiquity to have been an island completely devoid of woodland(see Strabo 10.5.2). Wood was therefore imported in great quantity, as it was required not only as a construction material for doors, windows and roofs, but also served as a combustible fuel. On the Delian market for firewood, see Reger 1994, 185–186. Generally, on the importance of supply and transport in ancient economies, see Warnking 2015, 136–149.Papyrus, on the other hand, had a long way to travel to Delos, as did more expensive types of wood like cypress. While tablets were locally produced in Delos and bought by the sanctuary’s administration in the local shops, papyrus was imported as a manufactured good. The importing of the material (including the costs of transport) from a medium-long distance does not, however, appear to have greatly influenced price formation, as papyrus costs were often similar to the cost of wooden tablets. This is probably due to the presence of a network of local vendors, which created a filter between the initial conditions of production and the final commercialization in Delos. Both prices were overall relatively stable throughout the period; however, since we usually have no knowledge of the exact quantity of papyrus purchased, this impression from the extant sources must be taken with caution.

If we considerchartesto have been a long roll composed of many sheets, then papyrus seems to have been even cheaper than tablets. Ifcharteswere always purchased as a roll, then papyrus should be considered – in spite of the fact that it was an imported good – as an extremely low-priced material. In this case,however, one wonders why it is not mentioned more often in accounts from the 4th and 3rd century BC. The widespread use of tablets may be explained by the need to display the documents to the public (for instance in the agora), at least for a period of ca. one month, as we can reconstruct from the monthly accounts written onleukomata. However, not every document needed to be displayed,and it seems likely that many tablets may have been destined to end up in the archive directly after having been written and approved. Again, it was likely the accessibility of the material that determined what was more convenient to use.

If the prices mentioned for papyrus refer not to rolls but to sheets, then the attested prices would fit better within the general trend. Papyrus sheets were definitely more convenient than adeltoswritten on cypress wood, although more expensive than commonleukomata,sanides, andpeteura.

The most probable explanation for the scarcely attested use of papyrus for documents is that it was less convenient than the solid, cheap, easily available,and locally produced tablets.

Although papyrus was commonly used since the archaic age for the publication of literary works, the circulation of papyrus for documentary praxis was relatively limited before the Hellenistic period, and the material remained (despite some price fluctuations) expensive until the middle of the second century BC,when papyrus seems to have conquered the market.

Stone stelae were of course comparatively expensive, even when they were produced from local marble, as they demanded skilled workers, entailed a relatively long production process, and were necessarily bound up with considerable extraction and transport costs. Nonetheless, since they were highly visible and unbreakable, they were the only material that guaranteed lasting for“eternity,” and overall they did not cost more than sacrificial cattle (which formed the bulk of the annual expenses in a sanctuary like Delos).91See Berti 2013.While stone stelae could obviously not be used for the everyday accounting or for contracts destined to be handed over to other parties, they remained an important writing material,not only for monuments, but also for administrative writing.

Rethinking the relation between the writing materials poses new questions:What is the meaning of theantigrafaof the stelae written ondeltoior – occasionally – onpeteura? If we consider them as copies for the archive, it would seem to be an unnecessary duplication of the same text, which was thus available on two different – and both relatively expensive – materials. Instead, I believe that the stelae should themselves be considered part of the archive. The copies written on mobile writing media would have thus had a different, and very practical, purpose, that of accounting during the delicate moment of the “transfer of power” between the old and the new board of administrators, when the Council, the Assembly, and the city magistrates had to supervise the sanctuary’s financial statements.

The accurate and detailed stelae had a legal function and were the only authoritative documents: they helped to track the responsibility of the administrators for the money spent on loans, festivals, sacrifices, restoration works, and all the other regular and extraordinary activities of an important sanctuary. While they rendered the incidental inaccuracies of past administrations visible – objects missing from the inventories, or incorrect procedures in the submission of the accounts – they publicly guaranteed the integrity and honesty of the current administrators. The last extant account and inventorystelaeproduced in Delos are dated to the 140s BC. Following this date the publication stops, but we can hardly believe that the sanctuary then stopped keeping account of its financial transactions. Can we imagine a change of the writing material for the annual account and inventory, perhaps in favor of papyrus? This suggestion must remain hypothetical, but it would fit the dating of the papyrus archive from Skardhana,which attests to a growing use of papyrus rolls for administrative documents after the middle of the second century BC.

Appendix

Tab. 1: Attested prices for letter-cutting in Delos

177 BC ID 444 A, l. 36 10 dr.174 BC ID 440 A + 456 B,(Chankowski 1998),ll. 60–61 ca. 130 dr. (2 stelae:260 dr.)172–170 BC ID 459, 64 370 dr.? (unknown number of stelae, but more than one)

Tab. 2: Production cost of the administrative inscriptions*

296–279 BC IG XI, 2,153,ll. 12–14 80 dr.for 2 stelae 2 stelae and a base: 30 dr.transport of the stelae and of the bases:3 ob.lead: 2 dr.3 ob.;wood: 1 dr.114 dr.281 BC IG XI, 2,159 A,ll. 65–67 85 dr.transport:price not preserved;1 dr. 2 ob.to erect the stelae lead: 2 dr.;wood: 1 dr.>89 dr.2 ob.279 BC IG XI, 2,161 A,ll. 117–119 100 dr. 25 dr.transport up to the sanctuary:1 dr. 3 ob.;erection of the stele:2 dr. 3 ob.lead: 5 dr.;wood: 1 dr.135 dr.274 BC IG XI, 2,199 C,ll. 66–80 126 dr.4 ob.one stele:24 dr.;base: price not preserved transport and erection of the stele:price not preserved lead: price not preserved>150 dr.4 ob.250 BC IG XI, 2,287 A,ll. 197–198 120 dr.transport:5 dr.; sealing to the base: 1 dr.lead and wood: 7 dr.4 ob. ½ ¼23 dr. for the fabrication of the stele and of the base 156 dr.4 ob. ½¼246 BC ID 290,ll. 118,136–137 180 dr. 3 dr. + 5 dr.transport to the sanctuary and installation of the stele lead: 6 dr.;wood:1 dr. 3 ob.35 dr. preparation of the stele;6 dr. fabrication of the base 236 dr.3 ob.

* The quantity of production details recorded varied from account to account and from year to year. Not every inscription mentions the entire production process of the stele; in addition to this, inscriptions are sometimes too fragmentary to reconstruct significant information. Entries which are left incomplete are either missing or unreadable on the stone.

Tab. 3: Prices of papyrus

sanides (quantity unknown), 1 dr.; one papyrus, 10 dr.258 BC IG XI, 2, 224 A 28 χάρτης· ˫˫I one papyrus, 2 dr. 1 ob.250 BC IG XI, 2, 287 A 50 χάρτης ˫IIII one papyrus, 1 dr. 4 ob.ibid. A 52 χάρτης ˫IIIII one papyrus, 1 dr. 5 ob.ibid. A 84 χάρτoυ ˫IIII·one papyrus, 1 dr. 4 ob.ibid. C 156 χάρτη<ς> ˫ΙΙΙΙ■ one papyrus, 1 dr. 4 ob. 1 tetartemorion 231 BC ID 316, l. 70 χάρτης ·˫III one papyrus, 1 dr. 3 ob.224 BC ID 338 A, l. 19 χάρτoυ ˫˫˫ for one papyrus, 3 dr.218 BC ID 354, l. 59 χαρτῶν ·˫˫˫■papyrus (quantity unknown), 3 dr. 5 ob.200 BC ID 372 A, l. 75 χαρτῶν II, ˫˫˫II for two papyri, 3 dr. 2 ob. (= 20 ob. =1 dr. 4 ob. each)179 BC ID 442 A, l. 183 χαρτῶν Π papyrus, 5 dr. (unknown quantity of papyrus)173 BC ID 456 B, l. 8 χαρτῶ[ν - ]unknown quantity of papyrus, price not preserved 267 BC IG XI, 2, 205 B frg. b+c, l. 2— [σανίδες?] ˫ χάρτης Δ

Tab. 4: Prices of chartes and chartion

Tab. 5: Prices of perishable writing materials (when not otherwise specified,prices are intended pro unit)

Bibliography

Ast, R. et al. 2015.

“Papyrus.” In: T. Meier, M. R. Ott and R. Sauer (eds.),Materiale Textkulturen.Konzepte – Materialien – Praktiken. Materiale Textkulturen 1. Berlin, Munich &Boston: De Gruyter, 307–321.

Berkes, L. et al. 2015.

“Holz.” In: T. Meier, M. R. Ott and R. Sauer (eds.),Materiale Textkulturen.Konzepte – Materialien – Praktiken. Materiale Textkulturen 1. Berlin, Munich &Boston: De Gruyter, 383–395.

Berti, I. 2013.

“Quanto costa incidere una stele? Costi di produzione e meccanismi di pubblicazione.”Historikά3: 11–46.—— 2019.

“I costi della scrittura pubblica.” In: G. Marginesu (ed.),Studi sull’economia delle technai in Grecia dall’età arcaica all’Ellenismo. Annuario della Scuola Archeologica di Atene e delle Missioni Italiane in Oriente, Supplemento 2.Athens: Scuola di Archeologica Italiana di Atene, 125–134.

Boussac, M.-F. 1993.

“Archives personnelles à Délos.”Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres137/3: 677–693.

Bülow-Jacobsen, A. 2009.

“Writing Materials in the Ancient World.” In: R. Bagnall (ed.),The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4–29.

Capasso, M. 1992.

“Le tavolette della Villa dei papiri ad Ercolano.” In: Lalou 1992, 221–230.—— 1995.

Volumen. Aspetti della tipologia del rotolo librario antico. Naples: Procaccini.

Chankowski-Sablé, V. 1997a.

“Le sanctuaire d’Apollon et le marché délien: une lecture des prix dans les comptes des hiéropes.” In: J. Andreau, P. Briant and R. Descat (eds.),Économie antique. Prix et formation des prix dans les économies antiques. Saint-Bertrandde-Comminges: Musée archéologique départemental, 74–89.—— 1997b.

“Les espèces monétaires dans la comptabilité des Hiéropes à la fin de l’Indépendance délienne.”Revue des Études Anciennes(Mélanges dédiés à la mémoire de J. Coupry) 99/3–4: 357–369.

Chankowski, V. 1998.

“Le compte des hiéropes de 174 et l’administration du sanctuaire d’Apollon à la fin de l’Indépendance délienne.”Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique122:213–238.—— 2008.

Athènes et Délos à l’époque classique. Recherches sur l’administration du sanctuaire d’Apollon délien.Bibliothèque des Écoles Françaises d’Athènes et de Rome 331. Athens: École Française d’Athènes.—— 2012.

“Delos et les matériaux stratégiques. Une nouvelle lecture de la loi délienne sur la vente du bois et du charbon (ID, 509).” In: K. Konuk (ed.),Stephanèphoros.De l’économie antique à l’Asie Mineure. Hommages à R. Descat. Bordeaux:Ausonius Éditions. 31–52.—— 2013.

“Nouvelles recherches sur les comptes des hiéropes de Délos: des archives de l’intendance sacrée au grand livre de comptabilité.”Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres2: 917–953.—— 2019.

Parasites du Dieu. Comptables, financiers et commerçants dans la Délos hellénistique. Athens: Ecole Française d’Athènes.—— 2020.

“Greek Sanctuaries as Administrative Laboratories: Bookkeeping Experience on Delos from Wood Tablets to Marble Steles.” In: A. Jördens and U. Yiftach (eds.),Accounts and Bookkeeping in the Ancient World. Legal Documents in Ancient Societies 8. Wiesbaden: Harassowitz Verlag, 64–73.

Coqueugniot, G. 2013.

Archives et bibliothèques dans le monde grec: édifices et organisation,Ve siècle avant notre ère – IIe siècle de notre ère. British Archaeological Reports International Series 2536. Oxford: Archeopress.

Degni, P. 1998.

Usi delle tavolette lignee e cerate nel mondo greco e romano. Messina: Sicania.Epstein, S. 2013.

“Attic Building Accounts from Euthynae to Stelae.” In: M. Faraguna (ed.),Archives and Archival Documents in Ancient Societies. Trieste: EUT, 127–141.

Faraguna, M. 2013.

“Archives in Classical Athens: Some Observations.” In: id. (ed.),Archives and Archival Documents in Ancient Societies. Trieste: EUT, 163–171.

Feyel, C. 2006.

Les artisans dans les sanctuaires grecs aux époques classique et hellénistique:à travers la documentation financière en Grèce.Bibliothèque des Écoles Françaises d’Athènes et de Rome 318. Athens: École Française d’Athènes.—— 2007.

“Le monde du travail à travers les comptes de construction des grandes sanctuaires grecs.” In: P. Brun (ed.),Pallas 74: Économies et Sociétés en Grèce classique et hellénistique. Actes du Colloque de la SOPHAU, Bordeaux, 30–31 mars 2007. Toulouse: Presses Universitaires du Mirail, 77–92.

Glotz, G. 1929.

“Le prix du papyrus dans l’antiquité grecque.”Annale d’histoire économique et sociale1/1: 3–12.

Huss, W. 2012.

Die Wirtschaft Ägyptens in hellenistischer Zeit. Munich: C. H. Beck.

Jördens, A., Ott, M. R. and Ast, R. 2015.

“Wachs.” In: T. Meier, M. R. Ott and R. Sauer (eds.),Materiale Textkulturen.Konzepte – Materialien – Praktiken. Materiale Textkulturen 1. Berlin, Munich &Boston: De Gruyter, 371–382.

Karamanou, I. 2016.

“The Papyrus from the Musician’s Tomb in Daphne (7449, 8517–8523).Contextualizing the Evidence.”Greek and Roman Musical Studies4: 51–70.

Lalou, E. (ed.). 1992.

Les tablettes à écrire de l’ántiquité à l’époque moderne. Actes du colloque international du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, Institut de France, 10–11 octobre 1990.Turnhout: Brepols.

Lewis, N. 1974.

Papyrus in Classical Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Linders, T. 1988.

“The Purpose of Inventories: A Close Reading of the Delian Inventories of the Independence.” In: D. Knoepfler (ed.),Comptes et inventaires dans la cité grecque. Actes du colloque international d’épigraphie tenu à Neuchâtel du 23 au 26 septembre 1986 en l’honneur de J. Tréheux.Neuchâtel: Faculté des Lettres,37–47.

Meiggs, R. 1982.

Trees and Timber in the Ancient Mediterranean World. Oxford: Clarendon Press.Meyer, C. and Sauer, R. 2015.

“Papier.” In: T. Meier, M. R. Ott and R. Sauer (eds.),Materiale Textkulturen.Konzepte – Materialien – Praktiken. Materiale Textkulturen 1. Berlin, Munich &Boston: De Gruyter, 355–369.

Migeotte, L. 2013.

“De l’ouverture au repli: Les prêts du sanctuaire de Délos.” In: S. L. Ager and R. A. Faber (eds.),Belonging and Isolation in the Hellenistic World. Phoenix Supplements LI. Toronto, Buffalo & London: University of Toronto Press, 316–324.

Mulliez, D. 1998.

“Vestiges sans atelier: le lapicide.”Topoi8/2: 815–830.

Pöhlmann, E. and West, M. 2012.

“The Oldest Greek Papyrus and Writing Tablets. Fifth-Century Documents from the ‘Tomb of the Musician’ in Attica.”Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik180: 1–16.

Preka-Alexandri, K. 1989.

“Seal Impression from Titani, a Hellenistic Metropolis of Thesprotia.”Pact.Revue du Groupe européen d’études pour les techniques physiques, chimiques et mathématiques appliquées à l’archéologie23: 163–172.—— 1996.

“A Group of Inscribed Seal Impressions of Thesprotia, Greece.” In:Archives et sceaux du monde hellenistique. Actes du Colloque de Turin 1993. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique Supplement 29. Athens: Ecole Française d’Athènes,195–198.—— 1999.

“Recent Excavations in Ancient Gitani.” In: P. Cabanes (ed.),L’Illyrie Méridionale et l’Épire dans l’Antiquité III, Actes du IIIe colloque international de Chantilly (16–19 Octobre 1996). Paris: De Boccard, 167–169.

Prêtre, C. (ed.). 2002.

Nouveau choix d’inscriptions de Délos. Lois, comptes et inventaires. Athens:École Française d’Athènes.

Reger, G. 1994.

Regionalism and Change in the Economy of Independent Delos, 314–167 B.C.Berkeley, Los Angeles & Oxford: University of California Press.—— 1997.

“The Price History of Some Imported Goods on Independent Delos.” In:J. Andreau, P. Briant and R. Descat (eds.),Économie antique. Prix et formation des prix dans les économies antiques. Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges: Musée archéologique départemental, 53–71.

Rhodes, P. J. and Osborne, R. (eds.). 2003.

Greek Historical Inscriptions, 404–323 BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sarri, A. 2018.

Material Aspects of Letter Writing in the Graeco-Roman World, 500 BC –300 AD. Materiale Textkulturen 12. Berlin & Boston: De Gruyter.

Skeat, T. C. 1982.

“The Length of the Standard Papyrus Roll and the Cost-Advantage of the Codex.”Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik45: 169–175.

Vial, C. 1984.

Délos indépendante.Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique Supplement 10.Athens: Ecole Française d’Athènes.

Warnking, P. 2015.

Der römische Seehandel in seiner Blütezeit. Rahmbedingungen, Seerouten,Wirtschaftlichkeit.Pharos 36. Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Worp, K. A. 2012.

A New Survey of Greek, Coptic, Demotic and Latin Tabulae Preserved from Classical Antiquity.Trismegistos Online Publications 6. Cologne & Leuven:Trismegistos, accessed under: https://www.trismegistos.org/dl.php?id=12(17.04.2021).

Journal of Ancient Civilizations2021年2期

Journal of Ancient Civilizations2021年2期

- Journal of Ancient Civilizations的其它文章

- PICTORIAL ELEMENTS VS. COMPOSITION? “READING” GESTURES IN COMEDY-RELATED VASE-PAINTINGS (4TH CENTURY BC)*

- WEALTHY KOANS AROUND 200 BC IN THE CONTEXT OF HELLENISTIC SOCIAL HISTORY

- REPUBLISHED TEXTS IN THE ATTIC ORATORS

- EARLY ROMAN SYENE (1ST TO 2ND CENTURY) –A GATE TO THE RED SEA?