Inter-individual differences in the responses to aerobic exercise in Alzheimer’s disease:Findings from the FIT-AD trialT

Fang Yu*,Dereck Salisbury,Michelle A.MathiasonT

Adult and Gerontological Health Cooperative,School of Nursing,University of Minnesota,Minneapolis,MN 55455,USA T

Received 20 March 2020;revised 29 April 2020;accepted 10 May 2020 Available online 4 June 2020

2095-2546/©2021 Published by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license.(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/)

Abstract Background:Despite the strong evidence of aerobic exercise as a disease-modifying treatment for Alzheimer’s disease(AD)in animal models,its effects on cognition are inconsistent in human studies.A major contributor to these findings is inter-individual differences in the responses to aerobic exercise,which was well documented in the general population but not in those with AD.The purpose of this study was to examine inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses to a 6-month aerobic exercise intervention in community-dwelling older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia due to AD.Methods:This study was a secondary analysis of the Effects of Aerobic Exercise for Treating Alzheimer’s Disease(FIT-AD)trial data.Aerobic f i tness was measured by the shuttle walk test(SWT),the 6-min walk test(6MWT),and the maximal oxygen consumption(VO2max)test,and cognition by the AD Assessment Scale-Cognition(ADAS-Cog).Inter-individual differences were calculated as the differences in the standard deviation of 6-month change(SDR)in the SWT,6MWT,VO2max,and ADAS-Cog between the intervention and control groups.Results:Seventy-eight participants were included in this study(77.4±6.3 years old,mean±SD;15.7±2.8 years of education;41%were female).VO2maxwas available for 26 participants(77.7±7.1 years old;14.8±2.6 years of education;35%were female).The SDRwas 37.0,121.1,1.7,and 2.3 for SWT,6MWT,VO2max,and ADAS-Cog,respectively.Conclusion:There are true inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses to aerobic exercise in older adults with mild-tomoderate dementia due to AD.These inter-individual differences likely underline the inconsistent cognitive bene fits in human studies.

Keywords:Alzheimer’s disease;Cognition;Dementia;Exercise;Physical activity

1.Introduction

In the United States alone,Alzheimer’s disease(AD)affected 5.8 million people at a cost of USD209 billion in 2019,and the number of those affected will reach 14 million and cost USD1.2 trillion by 2050.1Currently,AD cannot be prevented or cured because the majority of drug trials for AD have failed.2In contrast,substantial evidence has accumulated and supports the role of exercise in reducing AD risk by 30%to 40%.3-6Mechanistically,aerobic exercise may modulate AD neuropathology through biologically sound pathways by increasing cerebral blood flow,neurogenesis and synaptogenesis,brain-derived neurotrophic factors,anti-in flammation,gray matter volume,and functional connectivity,as well as by reducing AD β-amyloid load,tauopathy,neurodegeneration,insulin resistance,and oxidative stress.7,8However,the findings on the cognitive bene fits of aerobic exercise as a treatment for AD have been inconsistent,showing no effects9-12or only modest or moderate effects.13-19

Some of the inconsistencies in cognitive findings can be explained by methodological factors,such as differences in study samples and aerobic exercise doses.However,an overlooked but potentially major contributor is inter-individual differences in the responses to aerobic exercise.Inter-individual difference refers to the fact that not all individuals will respond to the same treatment to the same degree within the same timeframe or will have the same side-effect pro files.20The effect of inter-individual differences or individual heterogeneity in treatment responses has been well established for many chronic conditions,such as obesity and diabetes.The recognition of inter-individual differences in treatment responses led to the Precision Medicine Initiative in 2015,which takes individual variability in genes,environment,and lifestyles into account when analyzing treatment responses,thus optimizing treatment effectiveness.21One way to implement precision medicine is to identify early nonresponders to a treatment(e.g.,individual behavioral treatment for obesity)and implement adaptive interventions accordingly(e.g.,augment individual behavioral treatment with meal replacement)through innovative research methods such as the Sequential,Multiple Assignment,Randomized Trial(SMART).20

Within the context of precision medicine,precision exercise22,23has emerged as the critical next phase of exercise research due to the increasing recognition of inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness responses to aerobic exercise,which were first reported in twin studies and in studies of adult populations.24,25In one study,changes in maximal oxygen consumption(VO2max),a gold-standard measure of aerobic fitness,ranged from a reduction of 33.2%to an increase of 76.0%in premenopausal women who received the same aerobic exercise intervention,and in this study,about 30%of the participants experienced no improvement in aerobic fitness.26Similar inter-individual differences in VO2maxhave been reported in older adults with intact cognition.24,25However,a critical limitation in the existing studies is their use of the intervention-only arm of the randomized controlled trials(RCTs)without using the control group.27Using a control group is essential for identifying true inter-individual differences because it eliminates the in fluence of random trial-totrial variability.28The wordtruemeans that“the response differences are not merely random trial-to-trial variability in disguise”.28

Currently,inter-individual differences in the responses to aerobic exercise have not been studied in older adults with dementia due to AD.Recent RCTs did not find a main effect on or between-group differences in cognitive outcomes from aerobic exercise in older adults with dementia due to AD,but they did report a dose-response relationship between aerobic exercise and cognitive changes12and a positive association between aerobic fitness and cognitive improvements.11Hence,understanding inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness responses to aerobic exercise in AD is a critical next step in understanding aerobic exercise’s effects on cognition and in developing precision exercise for AD prevention and treatment.However,few studies have examined true inter-individual differences using the recommended method,28and no studies have done so in older adults with dementia due to AD.

The purpose of this study was to examine the inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses to a 6-month aerobic exercise intervention in community-dwelling older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia due to AD.The research questions were:(1)Are there true inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness responses to the 6-month aerobic exercise intervention?(2)Are there true inter-individual differences in cognitive responses to the 6-month aerobic exercise intervention?

2.Methods

2.1.Design

This study was a secondary data analysis of the Effects of Aerobic Exercise for Treating Alzheimer’s Disease(FIT-AD)trial data.The FIT-AD trial used a 2-parallel-group design to randomize 96 older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia due to AD to a 6-month aerobic exercise(cycling on recumbent stationary cycles)program or to an attention control(stretching)on a 2:1 allocation ratio.29Eligible participants were enrolled after completing baseline data collection and were randomized within 3 age strata(66-75 years old,76-85 years old,and 85+years old)using random permutated blocks of 3 and 6 participants.Allocation was concealed from all investigators except for the statistician and data collectors,who interacted with the participants only for data collection.29Aerobic fitness and cognition were assessed at baseline and at 3,6,9,and 12 months.The FIT-AD trial was approved by the University of Minnesota institutional review board(#1306M35661).Based on the assessment of decision-making capacity,participants signed informed written consent if they demonstrated decision-making capacity or assent while their informant signed surrogate consent.

2.2.Setting

The FIT-AD trial acquired consents and conducted cognitive assessments at the university’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute.Symptom-limited peak-cycle ergometer tests were performed in the Laboratory of Clinical Physiology.The intervention was delivered locally,in either a gymnasium or a retirement community.Study staff provided transportation for the participants.

2.3.Sample

The inclusion criteria for the FIT-AD trial included the following:(a)diagnosis of dementia due to AD veri fied by the participants’providers and investigators,(b)a Mini-Mental State Examination score of 15-26,(c)a Clinical Dementia Rating scale score of 0.5-2.0,(d)status as a community-dwelling adult 66 years of age or older,(e)English-speaking,(f)ability to safely exercise,as veri fied by the participants’primary care providers(and cardiologists,if needed),and(g)stability on AD drugs,if prescribed,for more than 1 month.The exclusion criteria included the following:(a)having a resting heart rate(HR)≥100 beats/min or≤50 beats/min,(b)having a neurological(e.g.,non-AD dementia or head trauma),psychiatric(e.g.,bipolar,schizophrenia,or depression),or alcohol-or substance-use disorder,(c)having new symptoms or diseases that had not been evaluated(e.g.,chest pain,thrombosis),(d)having abnormal f i ndings(e.g.,cardiac ischemia,inability to cycle)from the symptom-limited peak-cycle ergometer test,or(e)having other contraindications to exercise.29

To be eligible for this secondary analysis,the participants must have completed at least 1 aerobic fitness test or the cognitive assessment at both baseline and 6 months.Among the 96 participants enrolled in the FIT-AD trial,78 participants met the eligible criteria and were included in this study.Among these participants,26 participants’symptom-limited peak-cycle ergometer tests met the criteria to be deemed a maximal test at both baseline and 6 months.

2.4.Study procedure

In the FIT-AD trial,trained staff recruited participants through a variety of strategies(e.g.,referrals,educational seminars,community events,and newspapers)and screened them for study quali fication involving 4 steps:over-the-phone interview,in-person interview,con firmation of medical clearance,and exercise testing.Within a week of completing baseline data collection,participants started their assigned exercise activities,which included 3 sessions per week for 6 months,for a total of 72 sessions.The exercise interventionist supervised up to 3 participants per session.Each session included a 5-min warm-up and cool-down before and after cycling and stretching exercises.The sessions lasted 30 min at the start and were gradually lengthened to 60 min.

The cycling intervention involved cycling on recumbent stationary cycles at moderate to vigorous intensity(50%-75%of HR reserve derived from the symptom-limited peak-cycle ergometer test or a score of 9-15 on the Borg rating of perceived exercise(RPE)scale)for 20-50 min per session.The intensity and session durations were alternately increased by 5%of HR reserve(or 1 point on the RPE)or a 5-min duration increase over time.The stretching control included low-intensity range-of-motion movements and stretches and matched the frequency and durations of the cycling sessions.

During a session,exercise intensity was monitored using the Polar Wireless HR Monitor(RS400;Polar,Lake Success,NY,USA),Borg RPE,and talk test(ability to speak a sentence without catching breath multiple times)every 5 min.Blood pressure was recorded every 10-15 min,and overexertion signs and symptoms were continuously monitored.Participants left the site only after their HR and blood pressure returned to pre-exercise levels.The investigators performed f i delity checks on randomly selected sessions.29

2.5.Instruments

Aerobic fitness was measured by the shuttle walk test(SWT),the 6-min walk test(6MWT),and the symptom-limited peak cycle ergometer test.Cognition was measured by the AD Assessment Scale-Cognition(ADAS-Cog).Sample characteristics included age,sex,race/ethnicity,education,marital status,living arrangement,and AD medications.

The SWT is a progressive maximal field test,30which asks participants to walk around a 10-m course while being paced by an external beep.The participant has to walk from 1 marker to another for each shuttle prior to a beep.The time it takes to walk a shuttle is increasingly shortened;changes are noted by triple beeps as the walking speed progressively increases from 1.2 to 5.3 miles per hour at 1-min intervals for a total of 12 stages.Assistive devices were permitted.The test ended when the participant could not reach the marker before a subsequent beep.To ensure our participants completed the test properly,our data collectors provided verbal instruction by saying “stop”when participants arrived at the marker before the beep,“go”when the single beep for walking sounded,and“go and walk faster now”for the triple beep.The SWT is a reliable and valid assessment of aerobic fitness for older adults with multiple chronic conditions(interclass correlation coef ficient:0.91-0.97).31,32Peak walking distance,the cumulative distance walked,including the last completed shuttle,was recorded in meters and used for data analysis.

The 6MWT,a self-paced,submaximal aerobic fitness test,required the participants to walk as fast as possible on a marked,75-foot linear course in loops for 6 min.Standard encouragement using even,neutral tones was used for each participant,as recommended by the American Thoracic Society guidelines.33Assistive devices and rests with or without sitting were permitted.The 6MWT has high reliability for people with mild-to-moderate dementia due to AD;the interclass correlation coef ficient ranges from 0.982 to 0.987.34,35The peak walking distance,the total number of feet walked during the 6-min test,was recorded and used for data analysis.

The symptom-limited peak-cycle ergometer test was used to assess VO2maxin mL/kg/min with indirect calorimetry.36The test was performed in the postabsorptive state.The participant began to cycle at a comfortable speed(40-60 revolutions per minute),and the intensity was increased every 3 min by increasing the watts at 1 metabolic equivalent(1 MET=3.5 mL/kg/min,or the amount of oxygen consumed when sitting at rest)until the participant was fatigued or met the test termination criteria.36For this study,heart rhythm and rate were continuously monitored via electrocardiogram,while RPE and blood pressure were collected during the last minute of each stage.The test was deemed a maximal test when meeting at least two of the following criteria:(a)HR≥90%of the age-predicted maximum HR,(b)RPE≥17/20,(c)no increase in oxygen consumption with increasing exercise intensity,or(d)respiratory exchange ratio≥1.1.36

Cognition was measured by the ADAS-Cog.37The ADASCog assesses orientation,memory,recall,language,and praxis,with scores ranging from 0-70 and higher scores indicating worse function.ADAS-Cog has an inter-rater reliability of 0.65-0.99 and a test-retest reliability of 0.51-1.00.37

Sample characteristics,including age,sex,race/ethnicity,education,marital status,living arrangement,and AD medications,were collected using questionnaires administered to the participants and their family caregivers at baseline.

2.6.Statistical analyses

All variables were assessed using the appropriate descriptive statistics,means,and standard deviations(SDs)for continuous characteristics,and frequencies and percentages for categorical characteristics.All characteristics were tested between intervention and control groups.True inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses were calculated as the differences in the SD of change(SDR)in the walking distances from the SWT and 6MWT,the VO2maxfrom the peak-cycle ergometer test,and the ADAS-Cog score from baseline to 6 months between the intervention and control groups following the formula:where R=inter-individual responses,I=the intervention sample SD,and C=the control sample SD.28

Because“substantial greater variance in the intervention groupvs.control is both necessary and suf ficient for inferring true inter-individual differences in response to the intervention”in parallel group RCTs,27a substantially greater SDRin the SWT,6MWT,VO2max,and ADAS-Cog in the intervention group than in the control group means that true inter-individual differences are supported.Last,Pearson correlational analyses were performed to examine the relationships between attendance and the changes in aerobic fitness and cognition.All analyses were accomplished using Version 9.4 of SAS(SAS Institute,Cary,NC,USA).

3.Results

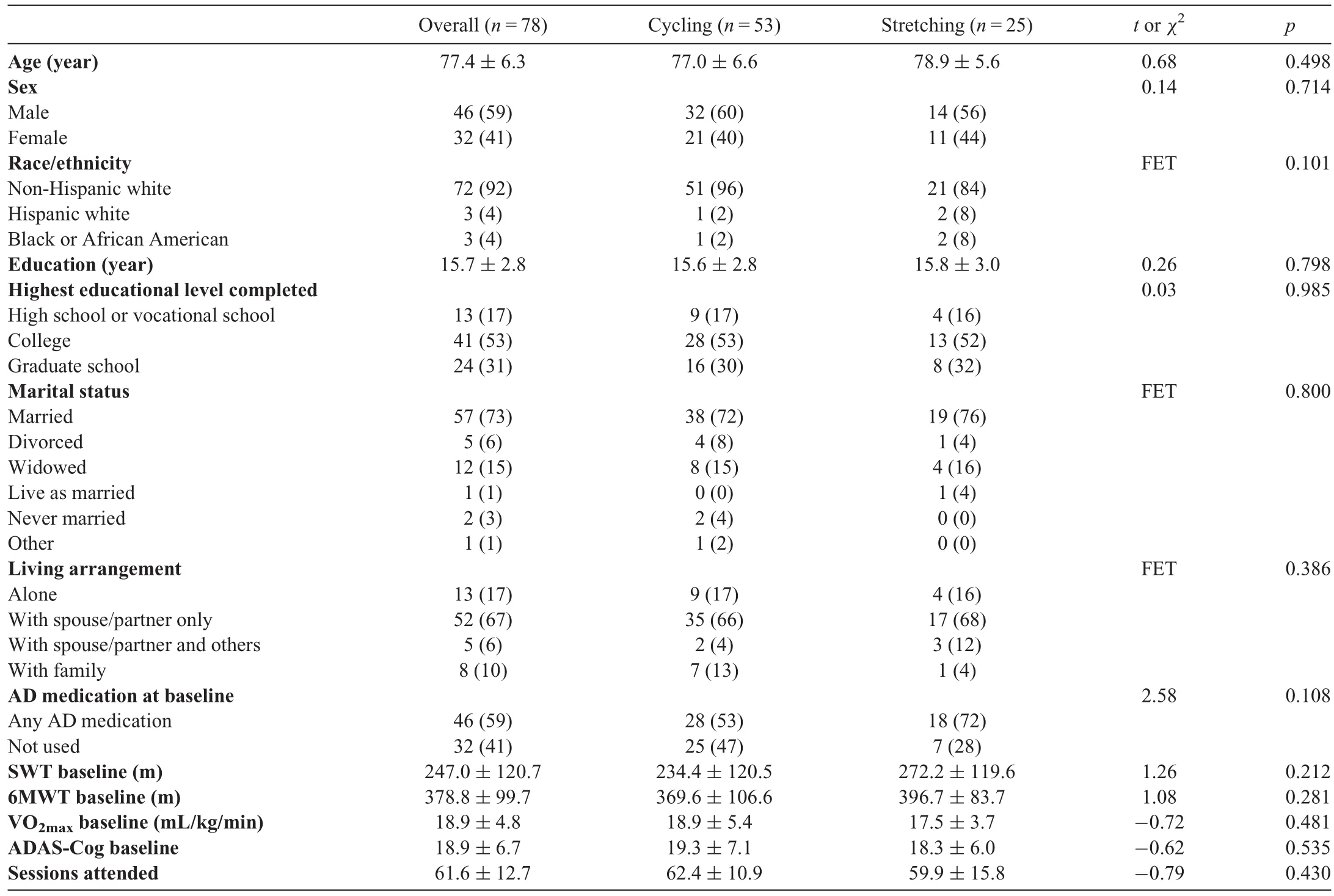

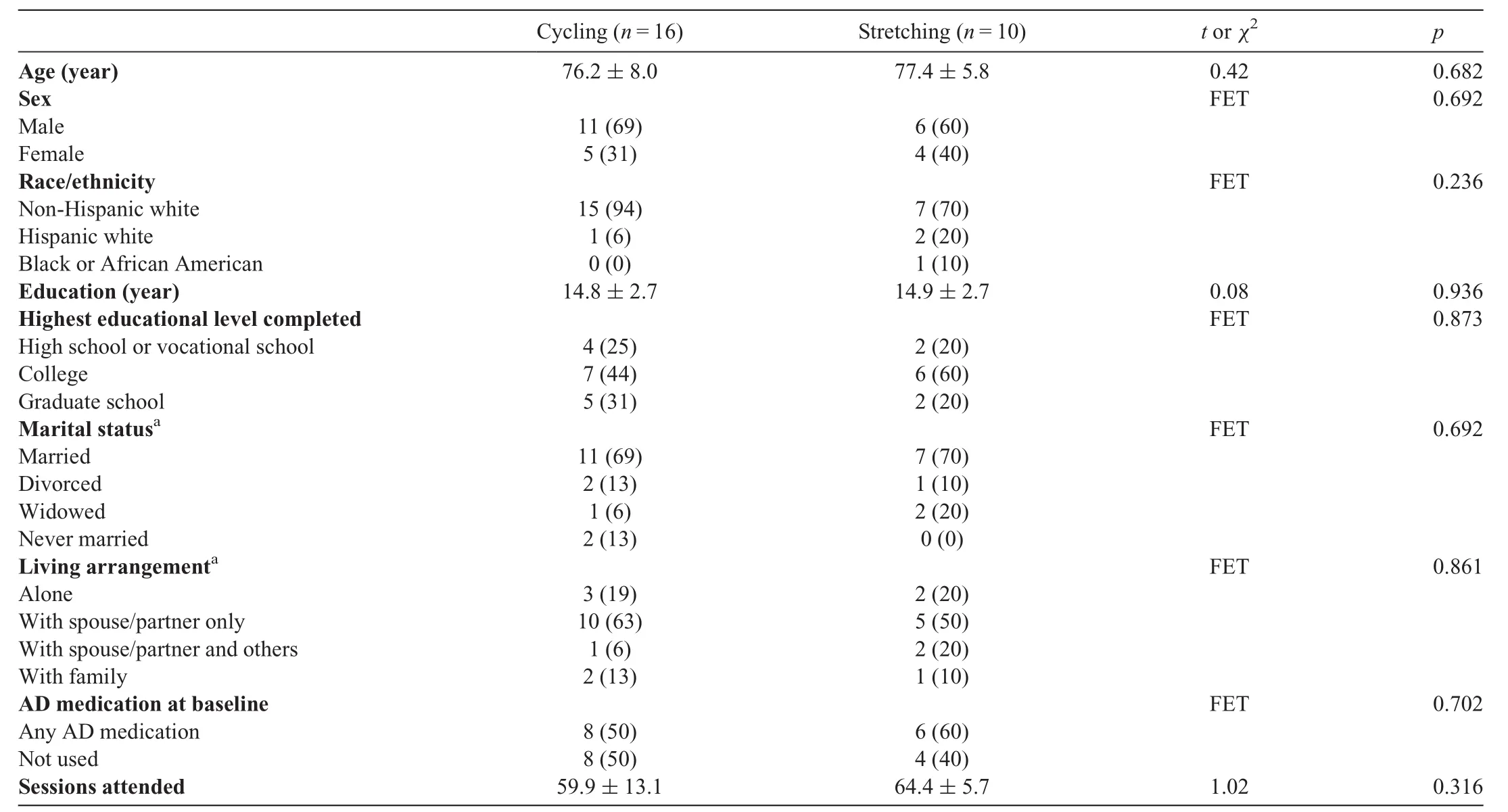

A total of 78 participants who met the eligibility criteria were included in this study:53 were in the intervention group and 25 in the control group.On average,those in the study sample were 77.4±6.3 years old and had 15.7±2.8 years of education(mean±SD).Of the sample,41%were female,92%were Caucasian,74%were married or lived as married,73%were living with spouses,and 59%were taking at least 1 AD medication.The sample’s baseline SWT distance was 247.0±120.7 m,its 6MWT distance was 1242.7±327.1feet,and its ADAS-Cog score was 18.9±6.7.The participants attended 61.6±12.7 of the 72 sessions.Of the 78 participants,26 reached maximal criteria on the VO2maxtest.The average age of these 26 participants was 77.7±7.1 years;they had an average of 14.8±2.6 years of education,and 35%were female.There were no statistically significant differences between the intervention and control groups in these characteristics at baseline for the overall study sample(n=78)(Table 1)or for the VO2maxsubgroup(n=26)(Table 2).

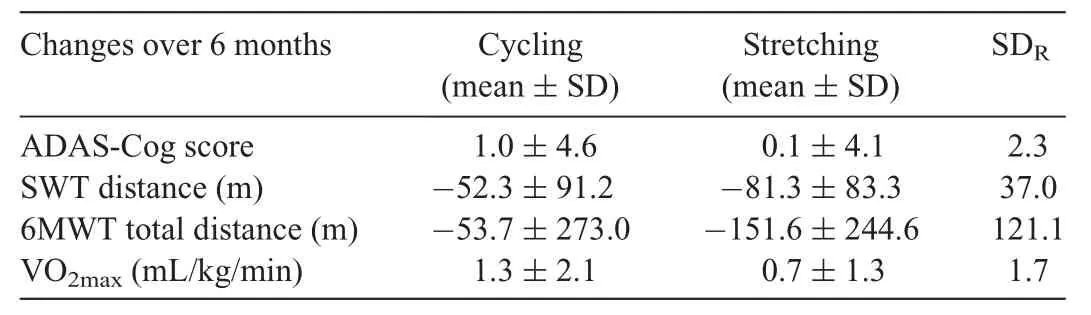

The intervention group had a greater SD than the control group on all 4 measures.The SDRwas 37.0,121.1,1.7,and 2.3 for the SWT,6MWT,VO2max,and ADAS-Cog,respectively(Table 3).

Table 1 Characteristics of the study sample(n=78,mean±SD or n(%)).

Table 2 Characteristics of the sample with baseline and 6-month VO2max(n=26,mean±SD or n(%)).

Table 3 Inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses.

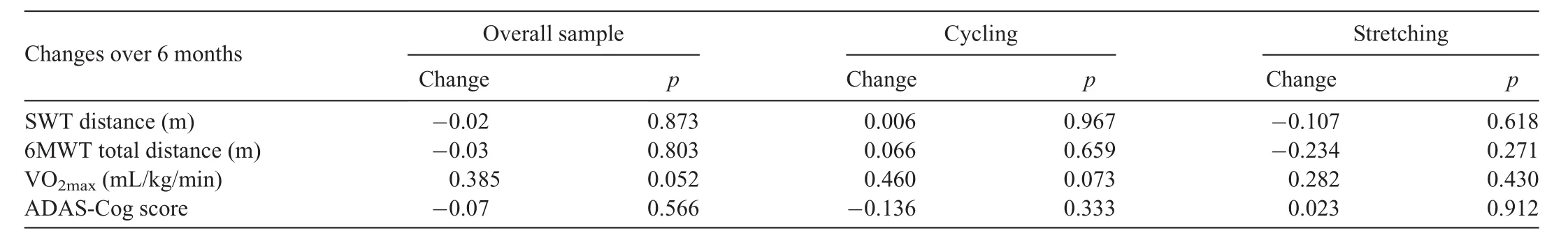

Pearson correlational analyses showed that attendance was not associated with the changes in the SWT(r=-0.02,p=0.873),6MWT(r=-0.03,p=0.803),VO2max(r=0.385,p=0.052),or ADAS-Cog(r=-0.07,p=0.566)for the overall sample.Attendance was not associated with the changes in the SWT,6MWT,VO2max,or ADAS-Cog in either the cycling or the stretching group(Table 4).

Table 4Pearson correlations of attendance and changes in outcomes.

4.Discussion

This study is the first to report inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses to a 6-month aerobic exercise intervention in community-dwelling older adults with mild-to-moderate dementia due to AD.Our results show that there are true inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses to aerobic exercise in this population.

Our findings of inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness responses to aerobic exercise are consistent with the literature.Studies using only the intervention groups to examine inter-individual differences have shown that VO2maxchanges that resulted from aerobic exercise interventions varied tremendously among the participants,ranging from a reduction of-33.2%to an increase of 76%in premenopausal women.26About 30%of the participants experienced no improvement in aerobic fitness.26Similar findings have been replicated in studies of older adults with intact cognition24,25and were,likewise,replicated in our study of older adults with dementia due to AD.There are multiple factors that contribute to improved aerobic fitness following aerobic exercise.Increases in aerobic fitness have been associated with concurrent improvements in calcium reuptake in the sarcoplasmic reticulum in myocardium and in left ventricular volume,which increases stroke volume and cardiac output.38Additionally,local skeletal-muscle adaptations such as increased mitochondrial density is a common finding,particularly following high-intensity aerobic exercise interventions.39The exact physiological mechanism of aerobic fitness nonresponse to aerobic exercise is not fully understood because there are many possible reasons that the response to exercise may vary.These reasons include nongenetic biological,behavioral,and exercise-programming factors,measurement errors,and day-to-day fluctuations.Human genetic studies show that inheritance,age,sex,and body mass account for about 50%of the VO2maxresponse variance in adults after adjusting for baseline VO2max.23

Our study addressed an important methodological gap in the current literature by employing the SDRmethod for capturing true inter-individual differences in exercise responses from both the intervention and the control groups.Using intervention-only groups contributes to false discovery because the identi fied inter-individual differences may be caused simply by random trial-to-trial variability.28For example,the changes in outcomes can result simply from the methods utilized by a given trial and from within-subject variability due to natural physiological and psychological changes over the duration of the study.27In contrast,the SDRmethod capitalizes on the use of both the intervention and the control groups and eliminates the in fluences of methodological factors that commonly vary from trial to trial,such as measurement errors and natural physiological changes of the outcomes over time.Also,the SDRmethod is not affected by unequal sample sizes between the intervention and control groups,which is common in RCTs due to different allocation ratios(e.g.,the 2:1 allocation ratio used in our trial),or by differential dropout rates in the intervention and control groups.As a result,the SDRmethod controls for random trial-to-trial variability in identifying true inter-individual differences in the responses to treatments.27

Our findings are the first to demonstrate the existence of true inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness responses to aerobic exercise in community-dwelling older adults with mild to moderate dementia due to AD.Despite the increasing recognition of the large inter-individual differences in aerobic f i tnessresponsesto exercise,27aerobic-exercise studies,including those involving older adults with dementia due to AD,have followed the traditional“main effects”and “mean group changes”approaches.Despite their usefulness,these traditional approaches(a)may hide a wide variety of responses by regressing contrasting responses to a mean;(b)cannot distinguish participants who bene fited substantially from the interventions from those who continued to decline despite the interventions;and(c)have been criticized for being misleading.27For example,the negative and positive responses even out each other in the intervention group and result in a lack of differences in outcomes when compared to the control group.Hence,our findings provide initial evidence of the critical need to apply a precision exercise approach21in future AD exercise trials.Aerobic fitness has been postulated as a physiologic mediator of aerobic exercise’s effects on cognition,40so our findings suggest that aerobic fitness could serve as the early tailoring variable to identify nonresponders and initiate augmented and adaptive interventions to improve outcomes in future SMARTs.

We also found true inter-individual differences in cognitive responses to the intervention.This finding is highly significant for the advancing of exercise research aimed at preventing and treating dementia due to AD because cognition has been a critical outcome for RCTs.The inter-individual differences in aerobic- fitness responses we observed may underline the mixed effects of between-group differences in cognition,which ranged from none9-12to modestormoderate effects.13-19,41-43Interestingly,2 recent RCTs did not find cognitive effects but did find a dose-response relationship12and an association between peak oxygen consumption(VO2peak)and cognitive changes in community-dwelling older adults with early AD.11These findings provide indirect evidence that inter-individual differences in exercise responses may be at play.Although we found inter-individual differences in cognitive responses,it is unclear whether such differences were attributable to inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness responses.Furthermore,repeated cognitive tests are subject to practice effects,and 6 months is considered to be the duration of aerobic exercise to exert cognitive effects.44,45As a result,we do not recommend using cognition as a tailoring variable in future SMARTs.

We did not find any associations between attendance and changes in aerobic fitness and cognition;however,this does not mean that aerobic exercise doses do not play a role in the inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses observed in our study.The change in aerobic fitness re flects the collective impact of aerobic exercise doses,including frequency/attendance,intensity,session duration,and program duration.Certain aspects of the exercise doses have been reported to affect outcomes independently.For example,exercise frequency and attendance in midlife was linked to reduced risk for dementia in older adults.46In addition,it is likely that exercise may affect cognition without the need to induce an improvement in aerobic fitness first.Recent evidence supports the idea that even light physical activity produces health bene fits compared to sedentary behaviors,47but its effect on cognitive outcomes remains unknown.In contrast,the inter-individual differences in exercise responses observed in our study were not caused by the exercise sites(gymvs.senior center).Both cycling and stretching exercises were standardized across sites and were individualized for each participant based on his or her HR reserve as assessed by the peak-cycle ergometer test.The same interventionist delivered all exercise sessions at both sites.The inter-individual differences also are not attributable to differences in participant characteristics;the sociodemographic characteristics did not differ between the 2 groups at baseline.

The strengths of our study include the use of the SDRstatistical method to determine true inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness responses and cognitive responses to aerobic exercise,thus capitalizing on both the intervention and the control groups in our RCT.Very few studies have included data from the control group,27and no similar studies have been done in older adults with dementia due to AD.Our study is limited by its small sample size(particularly for the VO2maxanalysis),by the limited racial and ethnic diversity of the participants,by the generally high education level of participants,and by the disparity in the exercise responses due to gender.The main reason we included only the participants whose tests met the maximal test criteria was to ensure the accuracy of VO2max.Although another 41 participants completed their peak-cycle ergometer tests at both baseline and 6 months,these tests were terminated prematurely due to our overemphasis on participant safety.Participants were not encouraged to cycle for maximal efforts even when they were capable of doing so.Our sample was largely white and had high level of education.Few participants who reached VO2maxwere female,and previous studies have not evaluated whether inter-individual differences in exercise responses differ by race/ethnicity,education,or gender.Hence,future studies with larger samples sizes are needed to validate our findings,particularly on VO2max,and to examine whether inter-individual differences in exercise responses vary by race/ethnicity,education,or gender.

Our findings have several additional research implications.If aerobic fitness is,indeed,a physiological mediator of aerobic exercise’s effect on cognition,it is logical to hypothesize that people whose aerobic fitness is sensitive to aerobicexercise interventions will receive greater cognitive bene fits.Our findings demonstrated that cognitive responses to aerobic exercise also vary among the participants,so it is likely that aerobic exercise might generate cognitive bene fits independently of the changes in aerobic fitness,especially in individuals who have low sensitivity to aerobic-exercise interventions.Both aerobic fitness and cognition showed inter-individual differences in the participants’responses to aerobic exercise in our study,so it is important to be able to predict aerobic fitness and cognitive responses to aerobic exercise interventions at baseline based on demographics,genes,lifestyles,comorbidity,and environmental factors,all of which call for other precision-medicine approaches.For example,omics and genomics can be used to discover biomarkers that predict exercise responses.Informatics will be useful in developing predictive algorithms and decision tools on the basis of demographics,lifestyles,and clinical indicators.Environmental redesigns may help to increase exercise attendance.48,49Clinically,our f i ndings suggest that an individualized approach to the prescription of aerobic exercise is essential in targeting clinically meaningful outcomes for each person.T

5.Conclusion

There are true inter-individual differences in aerobic fitness and cognitive responses to aerobic exercise interventions in community-dwelling olderadultswith mild-to-moderate dementia due to AD.Future studies that use an SDRapproach and that apply precision exercise are needed to validate our f i ndings and advance exercise research in AD.

Acknowledgments

This research study was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health(Award number:1R01AG043392-01A1).The Clinical and Translational Science Institute and the Center for Magnetic Resonance Resources were supported by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health(Award number:UL1TR000114)and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering(Award number:P41 EB1058941),respectively.The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the of ficial views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authors’contributions

FY designed and supervised all aspects of the study,analyzed results,interpreted findings,and drafted the manuscript;DS supervised all aspects of exercise,interpreted results,and drafted the manuscript;MAM conducted data analysis,interpreted results,and drafted the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2021年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Response to:Caution needed when interpreting muscle activity patterns during extremely low pedaling cadenceT

- Caution needed when interpreting muscle activity patterns during extremely low pedaling cadenceT

- Muscular activity patterns in 1-legged vs.2-legged pedalingT

- Exertional heat illness risk factors and physiological responses of youth football playersT

- Cardiorespiratory and muscular fitness associations with older adolescent cognitive controlT

- A person-centered approach to achievement goal orientations in competitive tennis players:Associations with motivation and mental toughnessT