沃菲尔德风土图记 XIX 宛转桥头

——苏州天平山范长白园遗址之思①

朱宇晖 Zhu Yuhui

徐瑞彤 译 Translated by Xu Ruitong

谭镭 译校 Proofread by Lui Tam

明天启二年(1622)六月,暑热未炽。山风习习的午后,姑苏城外西南诸峰中“林壑尤美”的天平山道,迎来了冠带俨然、韶华秀茂的张宗子。

群山如屏、高林阴翳间,扑入他眼帘的,是山脚下涧水汇注的一汪明湖。堤桥逶迤,盘桓山麓,望之不尽,显然经历了不动声色的整饬疏导;却又蒲苇怒长、清漪漫溢、乱石土岸,姿态横生,由人工而复归于天然,澄静地倒映着满山的颜色——那一瞬,曾经年少轻狂、餐霞饮露,对家乡绍兴兰亭的斧凿景色不惮微词的张宗子不由得凝住了脚步,他下意识地整一整衣冠,深吸一口气,正色向前——踏上了池上那座苍茂劲利、分水奔山的宛转桥。

宛转桥头的张岱会不会瞬间恢复了“狂奴故态”?

他时而回首侧睨着隔岸长堤在池中一线如画的倒影;时而俯首踮步,偷窥着脚下修长而又厚实的花岗石梁间不经意透出的脉脉池水和游鱼;时而倾身负手,竭力探出低矮粗犷的石穿木栏杆,憨态毕露地隔空狂嗅着才露一角的尖尖池荷;时而举头瞻望乱石如笏的天平横峰……时光静逝里,直角峻折的另一端桥头,那座故作低小的园门悄然带上了一抹午后的斜阳。园门里,就是祖父的同年进士范长白公的别业了。

数十年后,已是皤然一叟的张岱在《陶庵梦忆》中津津回忆道,“园外有长堤,桃柳曲桥,蟠屈湖面,桥尽抵园。园门故作低小,进门则长廊复壁,直达山麓。其绘楼幔阁、秘室曲房,故故匿之,不使人见也”——娓娓白描出的,正是一代山麓名园纳纵拔于横展、容丰富于纯净、高度克制而又饱含张力的空间妙趣。后来的崇祯十一年(1638)春月,已值不惑之年的张岱与好友探游“二十里松行欲尽,青山捧出梵王宫”的宁波府天童寺时,途经长松夹道、水田纵横,再经一汪如碧、万籁俱寂的“外万工池”,才豁然直面了巍巍太白山下,盈盈“内万工池”前从容横展、影入层漪的壮丽佛国。可事后,他不过以“到山门,见万工池绿净,可鉴须眉”数语带过,转而描绘寺僧样貌——或许再美的皇皇寺景,也抵不过少年时惊鸿刹那的心驰神纵;再庞大的建筑格局,也抵不过少年时苍山野塘之间,那一抹精心勾勒却又妙入无痕的空间层叠、横掠不尽之意,那一抹由几代文明巅峰积淀而成的审美高致、空间雅怀和时代芳华。

月盈则缺,人亦如此。

流连宛转桥头的张岱哪里知道,这妙入无痕、恍若无尽的芳华已经命悬顷刻了——仅仅23 年后,南明弘光元年(1645),清兵南下的铁蹄就已经踏碎了天平山下的宛转情思,和千里江南的文明晓唱、艺术层累。好在悠长近百年的生命和后半生的颠沛流离给了张岱足够的时间和对比,去回味宛转桥头这美好的荷风一度,就像暮年不得不孤独徘徊在东京都“后乐园”圆月桥头的朱舜水先生。

大约300 年后,另一个相似的时代,继起的才人童寯先生,身披着海国万里的烟涛微茫和抗战欲发的风雷隐隐,孤影茕茕,穿过苏州迎春坊的逼仄长街和奉直会馆的曲折避弄,从腰门步入了正沉浸在生命华光里的拙政园——在《江南园林志》中他深情写道:“今虽狐鼠穿屋,藓苔蔽路,而山池天然,丹青淡剥,反觉逸趣横生……”400 年名园山岛苍润、苇塘清漾、廊桥横逸、堤岸远引,于莫测的乱世中,诉说着悠远而纯净的庄严。

那一刹那,童寯先生如履天平道上,如入长白园中,如与300 年前的张宗子神遇而魂接。

也许从宛转桥头,那低伏的明湖长堤、矮垣折桥到园门内曲折的画楼幔阁、回廊深院,万千的横向诉说,一线的纯粹劲利,都是为了烘托一峰的苍然孤起,“万笏”的朝天之势。

也许惟有宛转桥头,那一带桃柳掩映着劲直的长堤,那一抹残阳斜照着质厚的垣墙,那一抹长山远树横掠过不尽的柳岸苇塘,惟有这样层叠横舒而又一线劲利、于纯净内敛中蕴含着无限庄严与伟大的景象,才能与仿佛发自远古的天平山头“万笏朝天”的磅礴力量相敌配,成就一代山麓名园的华彩篇章。

也许惟能横逸者能纵拔,能劲利者能舒缓,能纯净者能绚烂。也许惟有赖于时代的审美高度与自信,才能运斤成风,浑不着意地将二者斩截并陈、熔铸对比于一炉,才能以低平而素净的民居化小体量建筑组群、层叠而纯粹的横向线条烘托峻拔山势,映照潋滟波光。山愈雄而室愈静,墙愈素而枫愈丹,大处着眼,不事雕饰,逆峰运笔,愈简愈工——就像与张岱同时代的文震亨在《长物志》中所说的:“照壁,用金漆,或竟用素染。”就像300 年后常玉先生喃喃的:“我先画,然后再简化它,再简化它……”就像19 世纪80 年代冯纪忠先生留下的松江方塔园临湖立面,一线横绝,超凡入妙。

400 年前,天平山下的张宗子仿佛怀抱着审美的青春初悟,惆怅低回,行走在空间体验的长路,向潋滟处寻苍古,向横逸处求纵拔,于极简处得缤纷。青春烂漫,万般体味,暮年颠沛,一念归纯。

从那时至今,整个民族的空间审美,仿佛也伴随着后半生命运坎坷的张宗子,仆仆于文化复兴的长路,时出西泠印社衡门,时入方塔园堑道,时向象山校园。但更多时刻,则是沉溺于莺声燕语、红裳翠盖、陈家祠中、狮子林下,恨不能回归于400年前的天平山道、宛转桥头。

In June of 1622 (Year Two of Tianqi Emperor of Ming Dynasty), the summer sun was not yet blazing. On an afternoon simmered in the cool mountain breeze, along the trail of Tianping Mountain, whose forest and valley are the most beautiful among the peaks to the southwest of Suzhou, came the well-groomed Zhang Zongzi (also known as Zhang Dai), who was at the prime of his life.

Among the looming mountains and under the lush forest’s shadow, what leapt into his eyes was a luminously clear and pellucid lake, fed by the converging creeks flowing from the foot of the mountain. Endless embankment and bridges were winding through the foothills, which indicated deliberate yet unremarkable dredging and interventions. Meanwhile, the wild reeds, overflowing clear ripples, and the rocks and earthy shores of various postures quietly reflected the colours of the mountains, bringing one from the artificial back to nature. At that moment of encounter, Zhang Zongzi, who were once young and frivolous, who led a wandering life, and was contemptuous about the artificial scenery of his hometown, Lanting of Shaoxing, could not help but standstill. He tidied up his clothes subconsciously, took a deep breath, and moved forward sternly, stepping on the lush and vigorous Wanzhuan Bridge (Winding Bridge) that divided the water and ran across the mountains.

Would Zhang Dai on the Wanzhuan Bridge instantly have regained his ‘frivolous old manner’?

At times, he looked back in the pond at the picturesque reflection, of the long embankment across the lake; or bowed his head and walked on tiptoes, peeping at the flows of water and fish mindlessly passing by the cracks between the slender and thick granite beams underfoot; or leaned over and held out his hands, trying his best to reach over the low and rugged wooden railings piercing through stone pillars, childishly sniffing the fragrance of the sprouting lotuses in the pond; or looked up to the peak of Tianping Mountain with wild stones shooting up like sceptres. As time passed quietly, at the other end of the bridge after a square turn, the small and low garden gate was smeared with a ray of the peaceful setting sunshine. Inside the garden gate, it was the villa of Fan Changbai, a jinshi (metropolitan graduate) of the same year as his grandfather.

Decades later, Zhang Dai, already an older man, recalled with delight in his book Tao’an Mengyi:

Outside the garden, there was a long embankment. Peach trees, willows, and the zig-zag bridge were adorning around and across the lake. The bridge reached the garden at the end. The gate of the garden was purposely made low and small. As one entered the gate, there was a long corridor that led directly to the foothills. The pavilions decorated with paintings and curtains, secret rooms, and winding space, were all designed to create hideaways.

What he plainly described was indeed the whimsical space in the renowned mountain gardens of his time, where vertical and horizontal spaces were integrated, pure yet diverse, highly restraint yet full of tension. In the Spring of 1638 (Year 11 of Chongzhen Emperor), Zhang Dai, who was in his forties, explored Tiantong Temple in Ningbo Prefecture with his friends. The Buddhist temple ‘nestled among the green hills at the end of a 20-li long path flanked by pine trees’. They walked through the long path with pine trees and across the checkered paddy fields, then passing the clear and quiet Outer Wangong Pond, and were suddenly confronted by the magnificent Buddha-land under the towering Taibai Mountain. Its rippled reflection in the bright Inner Wangong Pond expressed a sense of ease. However, he only later described it with fairly simple words—‘At the temple gate, we saw the green and pure Wangong Pond, which was clear like a mirror’—before moving on to describing the monks. Perhaps even the magnificent view of the temple could not compare to the astonishment felt by a young racing heart. Even the grandest architecture could not compare to the adolescent experience among the green mountains and wild ponds, where spaces were layered meticulously yet seamlessly, and where one could experience the aesthetics of high-art, the elegant sense of space, and the glory of the era crystalised over several civilisations’ most remarkable achievements.

The moon wanes after it waxes, so do humans.

While lingering on Wanzhuan Bridge, Zhang Dai could not have anticipated that this wonderful, traceless, and seemingly endless beauty would be disrupted short after. Only 23 years later in 1645 (Year One of Hongguang Emperor of Southern Ming Dynasty), the Mandarin troops invading the south had crushed the subtle sentiments at Tianping Mountain, and the civilisation and artistic attainments in the vast land of Jiangnan. Fortunately, Zhang Dai’s almost a century’s long life and the displacement in his later years gave him enough time and distinctive experience to reminisce over the beautiful scene and lotus fragrance at Wanzhuan Bridge, just like Zhu Shunshui, who had to wander alone at the Yuanyue Bridge (Full Moon Bridge) of Korakuen in Tokyo in the evening of his life.

About 300 years later, in a similar era, another succeeding talent, Tong Jun, amidst the hazy mists and waves on his way back from the foreign land, and the brewing storm that was the Sino-Japanese War, walked through the long and narrow streets of Yingchun Fang (Spring Welcoming Neighbourhood) in Suzhou and the twists and turns of Feng-Zhi Guild and entered the side gate of Zhuozheng Garden (the Humble Administrator’s Garden), which was overgrown with the glory of nature. He wrote affectionately, ‘Nowadays, although foxes and rats wander through the houses and the roads are covered by moss, the mounts and ponds reclaimed by nature and the faded and exfoliated paintings on the buildings bring unexpected charm…’ in Gazetteer of Jiangnan Gardens. The renowned 400-year-old garden, harbouring the lush mounts and islands, the clear waves of the reed pond, the intricate crossing bridges and corridors, and the far-reaching embankments, expressed a sense of distant and pure solemnity in the unpredictable troubled times.

At that moment, it was as if Tong Jun were walking on the path of Tianping Mountain, entering Changbai Garden, and meeting with Zhang Zongzi’s soul from 300 years ago.

Perhaps from the Wanzhuan Bridge, through the low and long embankment of the luminous lake, the low wall, the zig-zag bridge, to the deeply-hidden painted towers and curtained pavilions, the winding corridors and secluded courtyards, the thousands of expressions across space, the pure strength and sharpness, were all to serve as a contrast to the towering lone green peak, creating an illusion of ‘tens of thousands of sceptres’ pointing towards heaven.

Perhaps only at the Wanzhuan Bridge, where peach trees and willows masked and cast their shadows on the long straight embankment, the thick walls were obliquely illuminated by the setting sun, and the outstretched mountains and distant trees traversed the backdrop of the endless willow bank and reed pond, illustrating a scene with ease and strength, infinite solemnity and greatness contained in purity and introversion, could the seemingly primaeval majestic power of the ‘thousands of sceptres pointing towards heaven’ at the top of Tianping Mountain be matched, giving rise to the glorious chapter of a famous foothill garden.

Perhaps only those who could be at ease laying low could leap high, those who could strengthen up when needed know how to relax, and those who could be pure could blossom. Perhaps only by relying on the high aesthetics and confidence of the times, could one lift the heavy with ease, deconstruct before synthesise, and use low and plain houses with small volumes in complex and layered and pure horizontal lines to serve as a contrast to the height and steepness of the mountain, reflected in the shines of the waves. The more majestic the mountain is, the quieter the rooms become; the plainer the walls are, the redder the maple leaves appear. Focusing on the overall contour, limiting the carvings and decorations, moving the brush against the tip, and making it simpler yet more sophisticated–just as Wen Zhenheng, a contemporary of Zhang Dai, said in Changwuzhi, ‘The screen should be finished with a transparent coating to showcase the timber material, but can occasionally be adorned with golden lacquer.’ Like what Chang Yu murmured 300 years later, ‘I draw first, then simplify it, and then simplify it again…’ Like the lake-facing side of the Fangta Garden (Square-Pagoda Garden) in Songjiang designed by Feng Jizhong in the 1980s, one single long and horizontal line was used to reach excellence and perfection.

400 years ago, Zhang Zongzi, who was at the foothill of Tianping Mountain, seemed to have grasped the first insight of aesthetics in his youth. Feeling melancholy, he experienced the space in his long stroll, looking for history in the glittering waves, seeking the high and upright among the low and humble, and searching for vibrancy in the minimalist. He experienced various adventures in his glorious youth, while the homelessness at the dusk of his life brought him back to a sense of purity.

Since then, the spatial aesthetics of the entire nation seems to have followed Zhang Zongzi, who experienced the turbulence of life in his later years and treading on the long way of a cultural renaissance. At times, it wanders between the Hengmen Gate of Xiling Seal Society’s Garden, the trench of the Square Pagoda Garden, and the Xiangshan Campus of China Academy of Art. More often, however, it is trapped in the extravagant decorations seen in the Chen Family’s Assembly Hall and the Lion Grove Garden, wishing only to return to the trail of Tianping Mountain and the Wanzhuan Bridge from 400 years ago.

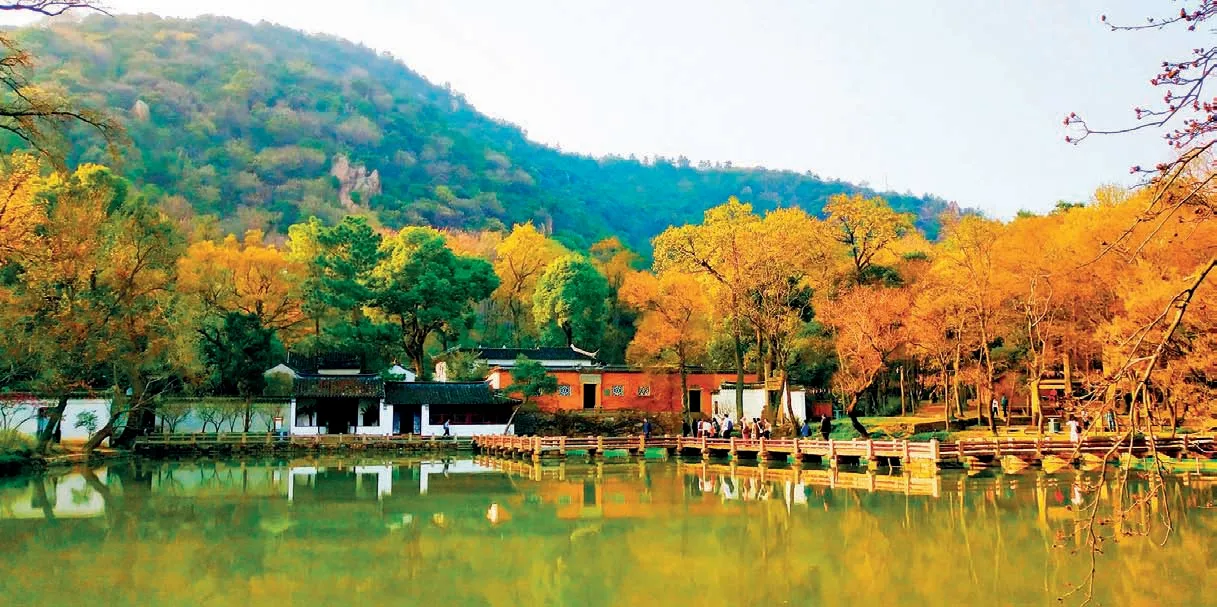

至今仍静卧于姑苏城西南天平山麓的明末范长白园(清中叶称高义园)旧址,或许是现存最美的山麓建筑群之一。其苍然横掠的山脊、一汪如鉴的平湖、西侧芳草逶迤的长堤和东侧凌波劲跨的横桥,或许都与400 年前张宗子踏访过的那个悠长午后并无二致。中央低平横展的建筑群,粉墙一带,重门深锁,也仿佛范长白园的传神再现。山风轻拂,画意舒卷间,旧时主人仿佛仍会应门而出——一晃已是400 年。

The former site of Fan Changbai Garden from the late Ming Dynasty (also called Gaoyi Garden in the mid-Qing Dynasty), which still lies to the southwest of Suzhou at the foothill of Tianping Mountain, is perhaps one of the most beautiful existing foothill architectural complexes. Its sweeping and lush mountain ridges, the placid lake as clear as a mirror, the long grassy embankment on the west side, and the bridge flying over the waves on the east side, may all remain the same since Zhang Zongzi’s on that long afternoon 400 years ago. Today, the low and spread-out group of buildings in the centre, the whitewashed walls, and the multiple impassable doors, also resemble a vivid reproduction of Fan Changbai Garden. As if in the gentle mountain breeze and the picturesque scenery of the garden, the old master would answer the door at any moment, even though 400 years have passed in a flash.

每逢霜风时节,旧日主人范允临(号长白)从福建泉州携来、栽植于天平山下的百余株枫香总会引领满山霜叶飞丹流霞,溢彩生光,映照黄墙素壁、碧水长桥,为山的苍劲、园的恬淡赋予斑斓张力,与岁弥新。

冯纪忠先生创作于20 世纪80 年代初的松江方塔园,亦是利用驳岸、绿植、长墙构成层叠劲利、绵亘不断的水平线条,映衬一塔的奋然孤起,获得饱满的张力与现代性。只需易塔为山,景象结构正与范长白园旧址前后相应。

Every frosty season, over 100 maple trees, brought and planted at the foot of Tianping Mountain by the old master Fan Yunlin (literary name Changbai) from Quanzhou, Fujian Province, paint the mountain with vibrant colours as the bright red maple leaves fly by and shine upon the bare walls, the green water and the long bridge, giving the vigour of the mountain and the tranquillity of the garden a colourful force year after year.

The Fangta Garden (Square-Pagoda Garden) in Songjiang, designed by Feng Jizhong in the early 1980s, also uses embankments, greeneries, and long walls to form layered, vigorous, and continuous horizontal lines, contrasting the singular vertical line of the pagoda, full of tension and sense of modernity. If we were to replace the pagoda with the mountain, the structure of the scenery would indeed resemble that of the site of Fan Changbai Garden.

宛转桥的列石横波、方角劲折,施用于城市地或觉突兀,施用于烂漫的山麓野塘,则如天籁横吹,信笔涂抹。自身材质语言与线条语言的粗犷有力,和周遭土岸石堤的逶迤不羁一样饱含自然张力,亦能与隔岸秀雅的接驾亭形成美妙对话,令人顾盼神飞,爱不忍释。

The rough stones, racing waves, and the twist and turns of the Wanzhuan Bridge might be abrupt if placed in an urban environment, yet set among the glorious wild pond at the foothill of a mountain, they possess the flair of heavenly music or one’s confident calligraphic strokes. The rugged and powerful language of their materials and contours is as full of natural tension as the surrounding unrestrained muddy banks and stone embankments. They also converse with the elegant Jiejia Pavilion (Welcoming Pavilion) across the pond, a scenery that brings up one’s spirit and makes it hard to turn away.

宛转桥的每一石条均减小宽度、刻意“修长”,以存速度感与方向感;同时加大厚度、刻意“质厚”,以存空间力感。且均留出向下一面不作凿平,其余各面亦加工适度,以保持自然山岩般的磅礴势能。其“建构”缜密有力而石缝参差,天趣盎然。两侧低伏的石穿木勾栏,亦于流畅的速度与力度间传递出丝丝温情。

Each bridge stone of the Wanzhuan Bridge has been reduced in width and deliberately made ‘slender’ to introduce a sense of speed and direction. Meanwhile, their thickness is deliberately increased to reserve a sense of spatial strength. Moreover, the bottom side of the stones is left unworked, and the other sides are also processed discreetly to retain the majestic energy of natural rocks. The rigorous and robust ‘tectonics’ accompanied by the irregular stones filled the scenery with natural charms. The low-hanging stone-pierced wooden balustrades on both sides convey warmth and tenderness among speed and strength.

天平山下野塘弥漫中横亘数重的芳草土堤,本应是宋明园林中的习见景象。清中叶起,名园多随土敷石,灭绝土岸,生气勃勃的自然地脉不得不屈从于匪夷所思的手法套路,近年的修缮与营造中发展更甚。陈从周先生曾批评修缮后的拙政园“满口金牙”。而天平山下的重重长堤土岸,无尽芬芳,不只承载过张宗子高风流连的脚步,也为园林史保存下了更近“高古”的手法印迹和鲜活姿态(堤头偏于工细的宫扇门墙经历了近年的新构)。

The wild pond at the foothill of Tianping Mountain, pierced by several grassy and soil embankments, would have been a familiar scene in the gardens of the Song and Ming dynasties. In the mid-Qing Dynasty, many famous gardens started to pave stones on the earthy ground as the earth banks went out of fashion. The vibrant natural ground had to surrender to the unthinkable techniques and routines, which became even worse in the recent restorations and reconstructions. Chen Congzhou once criticised the restored Zhuozheng Garden (Humble Administrator’s Garden) as ‘filled with golden teeth’. In this sense, the long embankments and the natural beauty at the foot of Tianping Mountain not only carry the footsteps of Zhang Zongzi’s lingers in the past, but also preserve the imprints of the more ‘ancient’ technique and vivid posture in the history of classical gardens (the exquisite gate and walls at the beginning of the embankment are recent reconstructions).

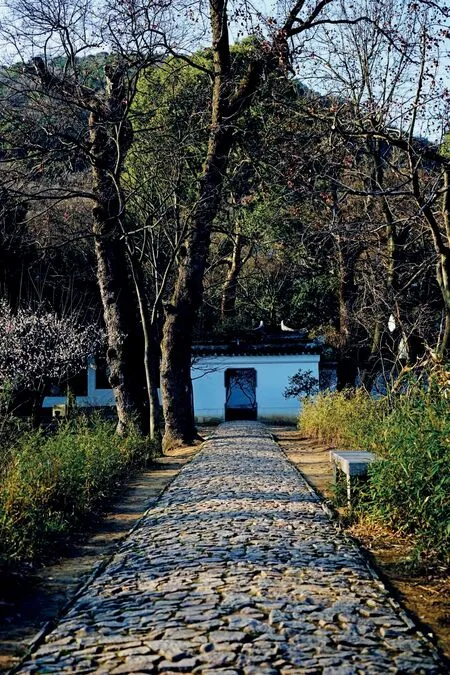

北宋仁宗以来,天平山即成为高风烈烈的范氏家族“坟山”——此甬路即为自园前横掠向左的神道,于咫尺高踞的翻经台下神态自若地凌波而过,令高台如巉岩入水,一径如秀堤分湖,将神性仪式与诗性景象融为一体,应是400 年前的原状。堤中平桥两座,拿捏精当。

山下重重野塘间浮现方形石台与栈桥一曲,建构简洁,转折方劲而微微出水,仿佛玉簟浮空、随波漫溢,与宛转桥的豪气横秋恰成鲜明对比,而又手法暗通。令人想见空山寂寂、野塘无人时的对月孤影(琐碎汀步系近年添加)。

Since the reign of Renzong in the Northern Song Dynasty, Tianping Mountain became the ‘cemetery mountain’ of the noble and righteous Fan family. This path was the divine passage in front of the garden that extended to the left, which gracefully passed by the Laiyan Pavilion (Swallow-Coming Pavilion) and Fanjing Platform towering above. The looming pavilion was like a cliff shooting from the water while the path a beautiful embankment separating the lake. This integration of divine rituals and poetic scenes would have been its initial state in the late Ming Dynasty 400 years ago. The two flat bridges in the middle of the embankment also represented the perfect proportion.

A square stone platform and a bridge emerge among the numerous wild ponds at the foot of the mountain. The structure of the bridge is simple, its turn square and sudden, standing slightly above the water surface as if a bamboo mat floating in the air and drifting with the waves. It appears in sharp contrast with the power of the Wanzhuan Bridge, except that the techniques are secretly connected. Recalling the image of a solitary soul facing the moon, standing alone by the wild ponds and the silent mountain (the scattered step stones in the pond were added in recent years).

园中今存掇山系就地取石,信手堆掇,兴会淋漓,大工不雕,仿佛凝固了自山头自然崩落而又“溅起”的刹那,饱含着浑朴而又磅礴的力量——相形之下,姑苏城内名园却一味以太湖石摹仿喀斯特地貌,有时背弃自然逻辑而追求过度变化,任意起峰,无限穿凿。无怪刘敦桢先生昔年过此曾加赞誉,张宗子到此,更当浮一大白(山头恩纶亭系近年重建)。

In the garden, the current rockery was piled up with local stones. The artist created it with such confidence and passion that he was able to express mastery without elaborate carving as if he had solidified the moment of a natural rock collapsing from and mountain and ‘splashing’ on the ground, full of unadorned and majestic power. In contrast, the famous gardens in Suzhou City blindly used Taihu stones to imitate the Karst landscape, to the point of betraying the logic of nature and pursuing excessive changes, with peaks rising arbitrarily and endless gouging. It is no wonder that Liu Dunzhen once praised the garden during his visit, and when Zhang Zongzi was here, he should have celebrated by drinking a full cup of wine. (The Enlun Pavilion on the mountain is a recent reconstruction.)

园东北侧有桃花涧,与范氏墓道穿插并行于高林间,汇注为桥堤纵横的园池(今称十景塘),再层叠漫溢而下,形成波光清漾、生气勃勃的陂塘水系。涧中有大石横亘中流,苍然如画,形成全园水口,显系在自然地形上稍稍加工而成。石畔的浅滩“闘(斗)鸭步”仿佛无锡寄畅园“鹤步滩”——都是遵循自然逻辑、举重若轻、浑若天成的理景妙笔。

The Taohua (Peach Blossoms) Stream was on the northeast side of the garden, parallel to the Fan family tombs’ divine path among tall woods. The stream flows into the pond of the garden (today’s Shijing Pond), crisscrossed by bridges and embankments, then flows down tiers of steps to form a wavy and vibrant series of ponds. There is a bulky rock in the middle of the stream, rough and picturesque, acting as the water gate of the garden, obviously a slight manoeuvre based on the natural terrain. Douyabu, the shallow beach near the rock, is similar to the Hebutan in Jichang Garden of Wuxi, both of which are brilliant landscape designs that resemble nature, follow the natural logic and lift the heavy with ease.

园西侧草创于唐代的白云古刹原为附着于范氏墓地的功德寺院,大殿内至今犹存北宋范仲淹时代的青石覆莲柱础,清中叶逸士沈三白来探访时却遭遇俗僧。民国年间于殿前添建的二门素朴简洁,饱含山寺气息。虽近年的修缮润饰过度,但黄墙一抹,字碑一横,仍能洒然映照千秋山林。

清乾隆前期于明末范长白园基础上修缮改建之高义园随坡叠起,至第四进逍遥亭下刻意收束空间,幽邃如岩洞,穿洞拾级而上,一回顾则有亭翼然,挑临深院,是山庄“宏大”叙事格局中的收束轻灵之笔。

The ancient Baiyun Temple to the west of the garden was founded in the Tang Dynasty as a family temple attached to the Fan family’s cemetery. Bluestone lotus column bases from Fan Zhongyan’s times of the Northern Song Dynasty still remain in the main hall. In the mid-Qing Dynasty, a free-spirit scholar, Shen Sanbai, came to visit but encountered a vulgar monk. The second gate built in front of the hall during the Republic of China era is neat and simple, full of the atmosphere of a mountain temple. Although interventions in the recent restorations were excessive, its yellow walls and stone stele still harmonise with the eternal mountain and forests.

Gaoyi Garden, renovated and rebuilt in the early Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty upon the previous site of the Fan Changbai Garden of the late Ming Dynasty, rose along the tiered slope. The space at Xiaoyao Pavilion in the fourth courtyard was deliberately compressed. The space deepened like a rock cave. As one climbed through the cave and looked back, a pavilion appeared, its eaves overhanging a deep courtyard—a delicate closing stroke of the villa’s ‘grand’ narrative.

高义园轴线南部尚有高义园坊与接驾亭。后者于近年重建后谦抑横舒,檐口低亚,不起屋脊,由始建时的堂皇作态而回归风土,与亭前从容横展、杂树横生之缓坡慢道(疑为乾隆前期遗物)同有由人工而归于自然之妙。

天平山门内的更衣亭以长六角形平面与乱石、山径最大限度地共形共势,盘桓欲发,直至凌空而起。其石柱凝立、石栏横护,翼角劲飞,极尽山亭之妙,与一线天下之梭形亭均以异形平面结为力感体块,融入巉岩乱石与自然地脉,非城市地园林中轻薄柔媚之小亭所能比拟,仿佛范长白园手法气质的溢出。

At the south end of Gaoyi Garden’s axis are the Gaoyi Garden Archway and Jiejia Pavilion. The latter one is humble and relaxed after the recent reconstruction, with low cornices and no rising roof ridges. It was a return to the vernacular form from the stately manner in which it was initially built. It shares the same ingenuity of a return to nature from the artificial as the gentle slope (hypothetically a relic from the early Qianlong period), overgrown with trees and calmly stretching in front of the pavilion.

The Gengyi Pavilion inside the Tianping Mountain Gate has an elongated hexagonal plan, echoing the chaotic rocks and mountain trails to the maximum extent, fluttering as if they were about to blast off high into the air. The stone pillars standstill, while the stone balustrade guards around them. The roof curls up sharply at the corners, consummating the wonder of a mountain pavilion. Similar to the shuttle-shaped pavilion under a narrow strip of sky confined by the cliffs, the irregularly shaped plan forms a masculine mass, blending with the chaotic rocks and the natural geology as if the style and technique of the Fan Changbai Garden had overflown its boundary, to which the light and soft pavilions in urban gardens are incomparable.

苏州留园西部土山上的至乐亭显然仿自天平山更衣亭与梭形亭,但地形相对平缓,乏力无势,不得不故作尖耸,致使檐口与举折过高,亲地性不足,更难以与山势取得共振。

The Zhile Pavilion on the earth mount in the western part of the Liu Garden (Lingering Garden) in Suzhou is an imitation of the Gengyi Pavilion and the shuttle-shaped pavilion on Tianping Mountain, but the cornices and the raising of the roof are too high, and the terrain is weak, making it look artificial and pretentious.

天平山白云泉(钵盂泉)亦见于沈三白《浮生六记》,其剖竹引泉,横出崖壁,注入钵盂,再次第溢出为“一泓清碧”的深潭,令自然泉流的汇注过程饱含转折跌宕的画意与雅趣,承继着白居易庐山草堂以来的悠久理水传统。自临泉小轩可俯瞰范长白园,空间依然一体。

The Baiyun Spring (Boyu Spring) of Tianping Mountain was also recorded in Shen Sanbai’s Fusheng Liuji. Split bamboos were used to guide the spring, flowing over the cliff into the ‘alms bowl’. The water then overflows again into a deep ‘crystal green’ pond. The natural spring’s path is full of the twist and turns, bringing out the quaint and charm of the picturesque. It inherits the long tradition of water management originated from Bai Juyi’s Lushan Cottage. The Fan Changbai Garden can be overlooked from the small pavilion by the spring, and the space is a harmonious whole.

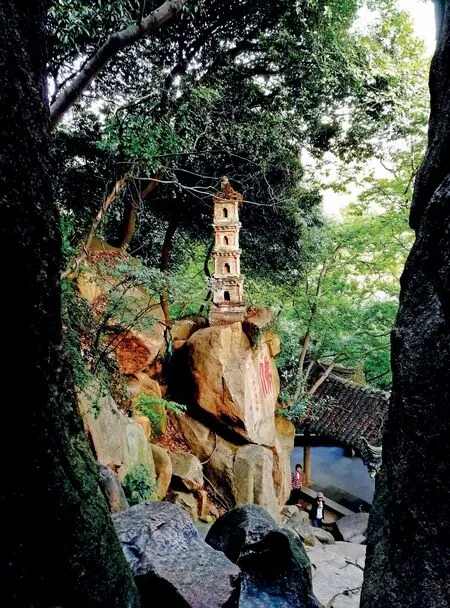

自更衣亭勉力登上一线天窄径,回望巨石壁立间,有一方劲古塔孤起如画,仿佛自山岩下的梭形亭腾跃而上——此段空间经营颇能体现苏杭小尺度山水的自觉“文人化”之美,亦仿佛范长白园之气质、力量源泉。该方形砖仿木楼阁式塔俗呼观音塔,疑是明以前旧物。

Climbing up the narrow path under a narrow strip of sky confined by the cliffs from Gengyi Pavilion, and looking back at the enormous rock walls, one can see a robust ancient pagoda standing alone like a painting as if it were leaping up from the shuttle-shaped pavilion at the bottom of the mountain. The spatial arrangement of this section illustrates quite well the conscious ‘literati’ beauty of the small-scale landscapes of the Suzhou and Hangzhou areas. It also feels like the source of the Fan Changbai Garden’s temperament and power. This square brick pagoda, imitating the form of a timber tower, is commonly known as the ‘Guanyin Pagoda’, hypothetically a structure from before the Ming Dynasty.