Effect of BATHE interview technique on patient satisfaction in an ambulatory family medicine centre in South India

Navnee Chengappa, Prince Christopher Rajkumar Honest, Kirubah David, Ruby Angeline Pricilla, Sajitha MF Rahman, Grace Rebecca

ABSTRACT

Objective The objective of the study is to determine the effect of background, affect, trouble, handling and empathy (BATHE) versus usual interview technique on patient satisfaction during regular consultation with family physicians in ambulatory care.

Design The research design was a prospective, randomised control trial.

Setting The trial took place in a family practice unit in South India, which was one of the clinical service units of the academic Department of Family Medicine of a tertiary hospital.

Participant The eligible participants were adults above the age of 18 years, who did not have any acute presenting illness. The participants should have given consent and also not have any cognitive disability. A total of 138 participants took part in the trial, 70 in BATHE group and 68 in the non- BATHE group. All participants entering the trial completed the questionnaire.

Result The BATHE group had a significantly higher mean score for questions grouped under professional satisfaction. This included questions on whether the patient felt that the physician treated them as a person and also whether they felt the appropriate clinical examination was communicated to them. The questionnaire used for scoring satisfaction had 18 questions with a maximum possible score of 90. When taking a cut- off of 75% (68) from the total possible score of 90, 72.9% (51) of the participants for whom the BATHE consultation technique was used were satisfied as compared with only 55.9% (30) for whom the routine consultation was carried out. This was statistically significant (χ2=11.15, p value=0.0006)

Conclusion The study suggests that using BATHE in this family practice centre is beneficial in improving the perception of person centeredness in the consultation. However, further studies ruling out all possible bias are needed in our setting before the range of probable benefits of the BATHE technique can be fully gauged.

INTRODUCTION

Psychosocial issues inclusive of personal, interpersonal, familial, societal and cultural events in an individual’s life determine how an individual responds to adverse life events like deterioration in their health.1Around 17%—46% of patients who attend primary care facilities have psychological issues related to mental health conditions like depression and anxiety.2Family physicians face the challenging task of addressing the clinical, social and psychological contexts of their patients and treating their emotional problems and common psychiatric illnesses.3Understanding and addressing the psycho—social issues along with medical problems to provide patient— centred care are shown to improve patient satisfaction, compliance and holistic care.4Family physicians need tools to address these issues during their regular consultations.5

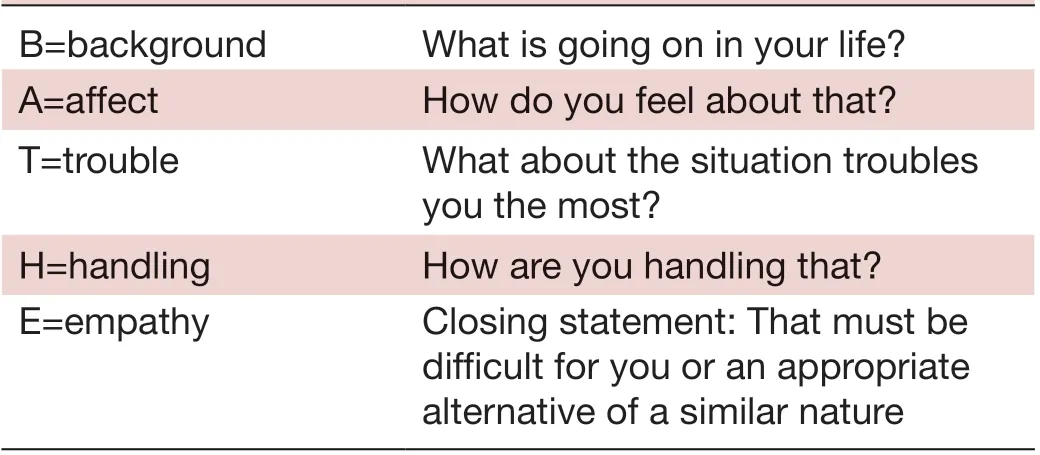

Background, affect, trouble, handling and empathy (BATHE), developed by Stuart and Lieberman, is a rapid intervention tool for theassessment of psychosocial factors in primary care.6The first four components consist of a series of questions that are asked by the physician inter— woven with the history of presenting report. The fifth question is an empathetic reflection by the doctor at the patient’s expression of psychosocial issues (table 1). The BATHE technique needs to be practised, just like any other aspect of medical history taking. The developers of this technique state that its mastery would enable the primary care practi—tioner to demonstrate patient centeredness and empathy while eliciting the psychosocial history at the same time. The simple BATHE technique aids the busy clinician to comprehensively manage the patient who may either be overly talkative or reticent.

Table 1 BATHE—the five components and their respective questions

The BATHE technique is helpful for counselling patients with psychosocial stressors and behavioural issues related to family life stages. The pioneers of this technique insist that it would take only 5—7 min to complete and would thus easily fit into the routine 10—15 min consul—tation slot of the family physician. Moreover, they recom—mend implementing this technique for every patient.7Since the emergence of this technique in 1986, it has been described and recommended for routine primary care consultations in many articles in the USA, UK and Canada.8—11

There is a paucity of literature in the subject of evalua—tion of the impact of BATHE technique either on patient satisfaction or outcomes of addressing psychosocial issues. Studies done in the USA in outpatient and inpatient care had demonstrated improved patient satisfaction when BATHE was used.1213A small— scale study done in Korean ambulatory care reported an increased level of patient satisfaction as well.14Additionally, a randomised control trial done in Turkey employing BATHE in patients with diabetic described improvement in Diabetic Empower—ment Scale.15However, there have been no reports of the application of this technique in India. Our study aims to add to the primary care research base for the use of BATHE in day to day consultations.

METHODS

Setting and participants

This study was conducted during January to February 2019, in Shalom Family Medicine Centre, an ambulatory service unit of the Department of Family Medicine at Christian Medical College, Vellore, India. The unit typi—cally has 180—200 patient visits in 1 day. Usually, it is staffed by three physicians everyday, two of whom are trained family physicians and one is a doctor who has completed MBBS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery) or a postgraduate family medicine resident. One among the trained family physician has consultations for the entire day on all days of the week, whereas the second family physician is posted in a roster of half— day schedule. The family physicians who consulted in the clinic were made aware of the BATHE technique and the study protocol in two academic sessions.

The sample size calculation was done based on the improved overall satisfaction score reported in the Korean outpatient study after implementing BATHE tool.14A minimum alpha error at 1% and maximum power at 90% for a two— sided test gave a sample of 32 patients to be randomly assigned to BATHE or non— BATHE tech—niques, respectively. The authors opted to enrol double the sample size. This was to ensure enough data for subse—quent analyses and to give an opportunity for all the family physicians in the centre to be randomised and imple—ment BATHE. The inclusion criteria were clinically stable patients above 18 years who consented to be part of the study and agreed to fill a patient satisfaction questionnaire after the doctor’s consultation. Patients who were acutely ill and those who needed immediate care and patients with cognitive decline were excluded. The patients in our family practice centre chose the family medicine consul—tant whom they wished to see in any particular day. Thus, the patients who consulted the physician randomised to use BATHE that day would receive the intervention. At the start of the working day, the consulting family physi—cians (two in number) were randomised to use BATHE or not in all the patients who had appointments to see them. They would not know which patient had given consent to be part of the study. The patient would not know whether they had the intervention or not. Following the consulta—tion, an independent blinded observer assisted patients in filling the patient satisfaction questionnaire.

Data collection and analysis

The questionnaire used to measure patient satisfaction was the Consultation Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ), which was an 18— item instrument that had been evalu—ated extensively and found to have good reliability and validity.16The CSQ has questions which are grouped into four scales. Three questions were grouped into general satisfaction with the consultation, seven with the experi—ential aspects of professional care (eg, the clinical exam—ination, explanation about the treatment, being treated as a person), five questions were grouped under the depth of relationship (feeling confident to share personal information, physician demonstrating understanding of the patient) and three questions covered the perceived length of the consultation.17

The response to each question is on a 5— point Likert— type scale extending from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. The questionnaire also included an open ques—tion asking for any other comment about the consultation. Additionally, the questionnaire included demographics of patients and physicians along with the nature of the visit (routine follow— up for a chronic condition or an acute care visit) and the number of previous visits to the same physician.

The software used for data entry and analyses was EPI data V.3.0 and SPSS V.16. While analysing the response of the CSQ, questions with positive response were scored as 5 for ‘strongly agree’ and in questions with the negative response, the score of 5 was given for ‘strongly disagree’. Thus, the maximum possible score in the CSQ was 90. The research team decided that patients scoring more than 68 (75%) would be classified as satisfied with the consultation.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of both groups were compared. The difference in mean scores when using the BATHE technique versus non— BATHE technique was calculated using the Mann— Whitney U test and the significant value was taken as p<0.05. Factors affecting satisfaction scores were studied using linear regression.

RESULTS

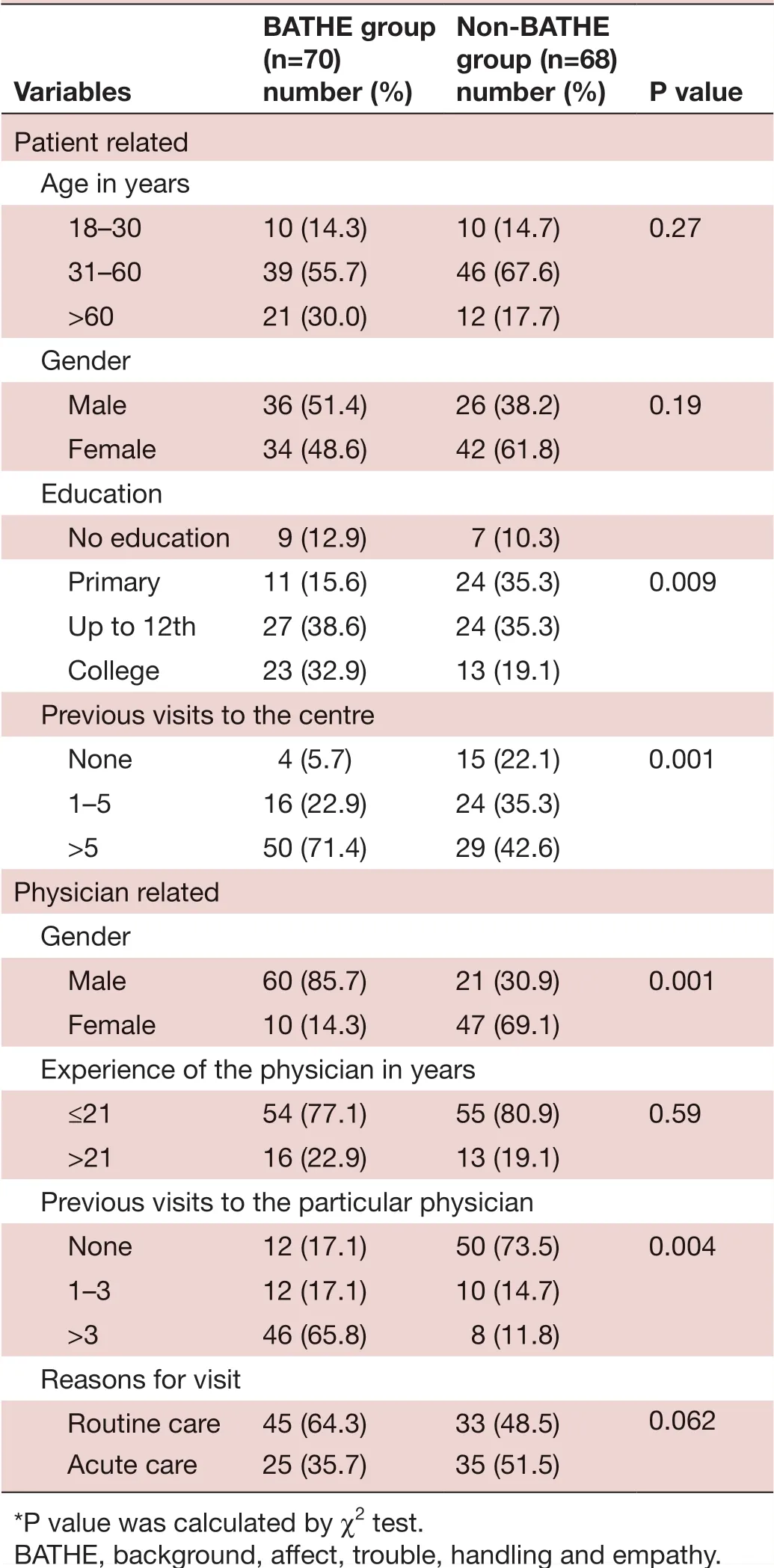

Around 70 patients were enrolled in the BATHE group compared with 68 in the non— BATHE group (table 2 and figure 1). Most patients in both groups were between 31 and 60 years. There was a higher proportion of female patients in the non— BATHE group with an equal propor—tion of male and female patients in the BATHE group. Patients in the BATHE group had a higher number of previous visits to the centre with the mean (SD) and a median of 9.6 (5.2) and 10, ranging from 0 to 20 visits. On the other hand, many patients in the non— BATHE group had visited the centre for the first time with the mean (SD) and the median number of 5.9 (5.1) and 4, ranging from 0 to 15 visits.

Patients in both groups were seen by family physicians with a minimum of 10 years experience. A higher propor—tion of patients in the BATHE group was seen by male physicians (85.7%, p value 0.001), consulted the same physician (65.8%, p value 0.004) and for regular care of chronic diseases (64.3%, p value 0.062) (table 2). On the contrary, patients with non— BATHE group had a higher proportion of consultation with female physicians with equal distribution of chronic disease follow— up (48.5%, p value 0.062) and acute care visits (51.5%, p value 0.062), predominantly seen for the first time.

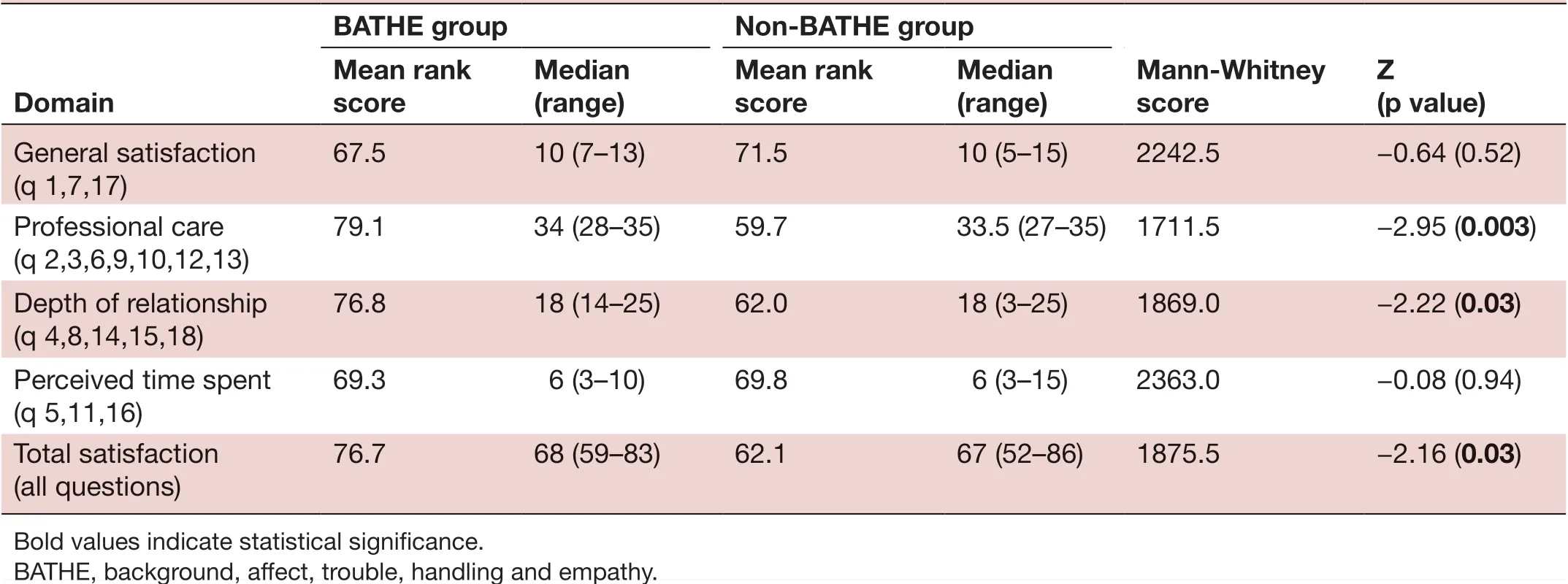

The total satisfaction mean rank scores (BATHE=76.7, non— BATHE=62.1, p value 0.03), professional care satisfaction mean rank scores ((BATHE=79.1, non— BATHE=59.7, p value 0.003) and the depth of relation—ship mean scores (BATHE=76.8, non— BATHE=62.0, p value 0.003) were significantly higher among the BATHEconsultation group than the non— BATHE consultation group. There was no significant difference in the general satisfaction scores (BATHE=67.5, non— BATHE=71.5, p value 0.52) and the perceived time spent (BATHE=69.3, non— BATHE=69.8, p value 0.94) between the two groups (table 3).

Table 2 Demographics

When taking a cut— off of 75% (68) from the total possible satisfaction score of 90, 72.9% (51) of the partic—ipants for whom the BATHE consultation technique was used were satisfied as compared with only 55.9% (30) for whom the routine consultation was carried out. This was statistically significant (χ2=11.75, p value≤0.0001).

Figure 1 Patient demographics influencing patient satisfaction scores. BATHE, background, affect, trouble, handling and empathy.

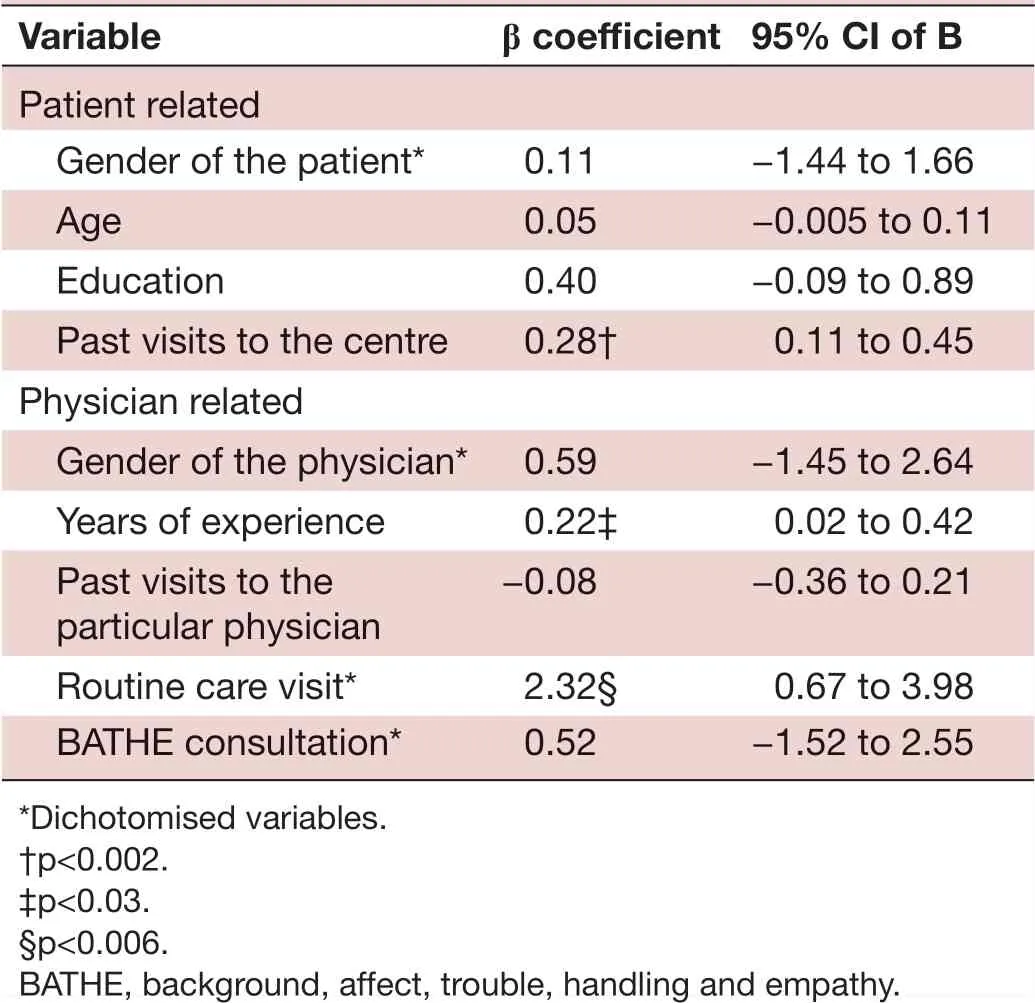

On applying linear regression, satisfaction scores were significantly higher among those who had visited the centre in the past and those who consulted physicians with more years of experience. There was association in past visits to the centre (beta=0.28, p<0.002), years of experience of the physician (beta=0.22, p<0.03) and visit for routine care (beta=2.32, p<0.006) with patient satis—faction scores. There was no association with BATHE consultation technique (beta=0.52, p<0.62) and patient satisfaction score (table 4).

DISCUSSION

Family physicians regularly encounter mental health issues like generic psychosocial distress, mood disor—ders and anxiety disorders that impair daily functions of patients. Moreover, they see patients with ongoing chronic problems like hypertension, diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who experience coping issues related to their disease and their life stages. These could represent as much as 30% of consultations on a routine day.1819The World Organization of Family Doctors working party for mental health encouragedfamily doctors to incorporate non— drug intervention (NDI) in everyday practice to manage mental health issues and thus provide holistic care.20BATHE technique is an example of NDI. The above research is the first study in the available literature on the use of BATHE in a family practice centre in India. Our trial demonstrated that BATHE is applicable in such a setting.

Table 4 Factors influencing the total satisfaction score

Patient satisfaction, to put it simply, is the extent to which patients are happy with their experience of a particular healthcare unit. There are a variety of methods to measure this. Our study used CSQ to measure patient satisfaction in two groups of patients, one of whom had BATHE technique of interview. There was no significant difference in the overall score of patient satisfaction in the two groups. The number of male physicians in theBATHE group was more than in the non— BATHE group. This was to be expected as the regular family physician available daily for the entire day was of the male gender. The patients had an established relationship with this physician.

Table 3 Comparison of domain specific and total mean rank scores of patient satisfaction for the BATHE and non- BATHE groups

We attempted cut— off scores ranging from 50% to 75% for the overall patient satisfaction score. When the cut— off of 75% was considered, the BATHE group had a signifi—cantly higher satisfaction score. There was a significantly higher score in the questions grouped under the profes—sional care scale in the BATHE group. The professional care domain of the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire includes elements vital in the patient— centred interview. Besides attentiveness and thorough physical examina—tion, it includes explicit explanation, acknowledging the person of the patient, enabling patients to understand their illness and follow physicians’ instructions. A higher score in this domain among participants in the BATHE group in our study reflects that patients felt satisfied when their context was explored and acknowledged. Patient satisfaction is well reported to improve self— management and compliance.4

A recent randomised controlled trial using BATHE to improve the care of frequent attenders of patients in general practices in the UK has documented BATHE to facilitate patient activation and lower consultation rates.21Patients in both the groups in our trial felt that the time spent with their physicians was inadequate for physicians to plan for all their issues during the consultation. Our study outcomes did not include the length of consulta—tion between the two groups. However, the recent UK trial reported no increase in consultation length as the BATHE technique gives a framework to explore patients’ wider contexts.21

Some of the significant predictors of patient satisfac—tion in our study group were consultation with an experi—enced physician, if it was a routine visit and if the patient had visited the clinic before. BATHE intervention was not a significant predictor of patient satisfaction. This is in contrast to the randomised controlled trial using BATHE to improve diabetic empowerment score in Turkey, where BATHE intervention was a positive predictor for improve—ment in diabetes empowerment scale (DES).15

The results of our study need to be moderated with the limitations. Due to scheduling issues in the duty roster, two family physicians were not always available for rando—misation. This resulted in significant differences in the baseline criteria of both groups. As both the family physi—cians were trained in BATHE, there was no guarantee that similar questions would not be used in non— BATHE consultation. This may have affected the patient satisfac—tion score.

Moreover, the patient satisfaction score was collected by an independent observer and not done directly by the patient. A point to be noted though is that the indepen—dent observer did not know about the BATHE consul—tation technique or its outcomes. Though we had not documented the time of each consultation, the physicians expressed that BATHE helped in quickly assessing the psychosocial factors in the visit and helped in relating to the patient as a person.

CONCLUSION

Our study illustrates that a simple intervention tool, like BATHE, can be used in primary and secondary care settings in India. The study results support similar findings in the literature that patients perceived patient centered—ness and had better total satisfaction scores when BATHE was used during consultation. BATHE as a screening and therapeutic tool can be taught for family medicine resi—dents and MBBS graduates practising in similar set— ups in India to explore the psychosocial issues in a structured format and empower patients to manage their problems better.

AcknowledgementsThe authors want to extend special gratitude for Mrs Premilla for helping out as an independent observer and to all the nursing and support staff in the Shalom family medicine centre for enabling the smooth running of this research.

ContributorsAll authors were involved in the original idea and design of the research, study design, in interpretation and finalising conclusions. NC and PCRK were involved in data collection. The original manuscript was created by NC, PCRK, KD and SMFR. The review of the manuscript was done by PCRK, KD, RAP and SMFR. Technical support, critical revision and statistical revision were done by RAP and GR.

FundingThe authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not- for- profit sectors.

Competing interestsNone declared.

Patient consent for publicationNot required.

Ethics approvalEthics Committee registration number: ECR/326/INST/TN/2013 Re Reg-2016. Issued under rule 122D of the Drugs and Cosmetics Rules 1945, Govt of India. Approval ID: IRB: 11365 (INTERVEN) dated: 27.06.2018.

Provenance and peer reviewNot commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statementData are available upon reasonable request. Data are available upon request from the corresponding author ( prince. christopher@ gmail. com).

Open accessThis is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY- NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non- commercial. See: http:// creativecommons. org/ licenses/ by- nc/ 4. 0/.

Family Medicine and Community Health2020年4期

Family Medicine and Community Health2020年4期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- How well did Norwegian general practice prepare to address the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Perceived barriers and primary care access experiences among immigrant Bangladeshi men in Canada

- Family medicine residency training in Ghana after 20 years: resident attitudes about their education

- Bridging the mental health treatment gap: effects of a collaborative care intervention (matrix support) in the detection and treatment of mental disorders in a Brazilian city

- Cultural adaptation and content validity of a Chinese translation of the ‘Person- Centered Primary Care Measure’: findings from cognitive debriefing

- Depression, periodontitis, caries and missing teeth in the USA, NHANES 2009-2014