Donor-specific cell-free DNA as a biomarker in liver transplantation: A review

Tess McClure, Su Kah Goh, Daniel Cox, Vijayaragavan Muralidharan, Adam G Testro,

Tess McClure, Adam G Testro, Liver Transplant Unit, Austin Health, Heidelberg 3084, VIC, Australia

Su Kah Goh, Daniel Cox, Vijayaragavan Muralidharan, Department of Surgery, Austin Health, Heidelberg 3084, VIC, Australia

Alexander Dobrovic, Department of Surgery, The University of Melbourne, Heidelberg 3084, VIC, Australia

Abstract Due to advances in modern medicine, liver transplantation has revolutionised the prognosis of many previously incurable liver diseases. This progress has largely been due to advances in immunosuppressant therapy. However, despite the judicious use of immunosuppression, many liver transplant recipients still experience complications such as rejection, which necessitates diagnosis via invasive liver biopsy. There is a clear need for novel, minimally-invasive tests to optimise immunosuppression and improve patient outcomes. An emerging biomarker in this ‘‘precision medicine’‘ liver transplantation field is that of donorspecific cell free DNA. In this review, we detail the background and methods of detecting this biomarker, examine its utility in liver transplantation and discuss future research directions that may be most impactful.

Key Words: Biomarkers; Precision medicine; Donor-specific cell-free DNA; Liver transplantation; Rejection; Review

INTRODUCTION

Liver transplantation (LT) is a crucial treatment option for many patients with advanced liver disease. Since it was first performed in 1963[1], LT has evolved so significantly that it has revolutionised the prognosis of previously incurable conditions. Today, recipients have overall survival rates of 96% at one year, 71% at 10 years and–remarkably–52% at 20 years post-LT[2]. In line with these excellent outcomes, the number of LTs performed each year continues to rise. In 2017, more than 32000 LTs occurred worldwide–representing 23.5% of the total organs transplanted and a 16.5% increase in LTs since 2015[3].

Long-term, the success of a LT depends on a fine balance: Adequately suppressing the immune system to avoid organ rejection, whilst maintaining it at a level that prevents complications and minimises side effects. Notably, the level of immunosuppression required post-LT can vary substantially between recipients. Whilst some patients are highly prone to rejection[4], others can successfully wean off immunosuppression entirely–achieving ‘‘operational tolerance’‘[5]. Despite the judicious use of immunosuppression, up to 27% of LT recipients still develop an episode of acute rejection and 68% encounter infective complications[6-8]. LT recipients also experience increased rates of malignancy, renal impairment and metabolic syndrome compared to the general population[9-11]. These issues can threaten graft and patient survival, impair quality of life and prove costly to manage[12-14].

Currently, the standard of care post-LT involves commencing recipients on empiric doses of immunosuppression, which are adjusted according to changes in liver function tests (LFTs), serum drug levels or the onset of an adverse clinical event. Whist LFTs are an extremely sensitive test for detecting organ injury, they are poorly specific for LT complications[15]. Moreover, no clear LFT thresholds exist that are diagnostic of rejection or reflective of its severity[16]. Similarly, there are no defined therapeutic ranges for serum calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) levels[17], as these have been shown to poorly correlate with clinical effects–particularly in LT[18]. Therefore, these tests often lead to a series of radiological and endoscopic investigations, that culminate in a liver biopsy to diagnose rejection. Not only is this process time-consuming and resourceheavy, but liver biopsies are inherently subjective and invasive[19]. Approximately 1 in 100 result in major complications and 2 in 1000 lead to patient death[20,21].

Clearly, innovative tools are needed to optimise immunosuppression and improve patient outcomes post-LT. Ideally, such tests should be both sensitive and specific for LT complications, as well as minimally invasive and cost-effective[22]. These tests also need to be easily accessible and rapidly performed, as changes in a LT recipient’s condition can occur quickly[23], and clinicians need to make prompt decisions in real time. To date, there has been considerable research into identifying biological markers that could enable clinicians to more precisely tailor immunosuppression regimens to individual patients[24-26]. One such emerging biomarker in this field of ‘‘precision medicine’‘ is that of circulating free DNA from the donor graft (i.e.‘‘donor-specific cell-free DNA’‘). In this review, we detail the background and methods of detecting this biomarker, examine its utility in LT, and discuss future research directions that may be most impactful.

DONOR-SPECIFIC CELL-FREE DNA

Background

Unencapsulated or ‘‘cell-free’‘ DNA was first discovered in human plasma by Mandel and Metais in 1948[27]. Following a resurgence of interest into its clinical potential in the 1990s[28], the scientific community has since learnt much about the biology of cell-free DNA. The majority originates from haematopoetic cells such as leukocytes[29,30], and is released into the circulation during apoptosis and necrosis[31-33]. These fragments of DNA are then rapidly cleared from plasma by the liver, spleen and kidneys[34,35]. As a result, cell-free DNA has a short half-life of approximately 1.5 h[36,37]–rendering it a ‘‘real-time’‘ marker of cellular injury. Subsequently, scientists identified that lower levels of this circulating free DNA were also being released during normal physiological turnover[38-40].

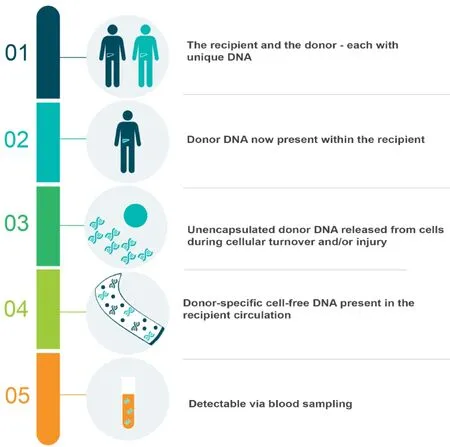

Given these characteristics, cell-free DNA has emerged as a useful biomarker in multiple clinical settings. This was particularly notable in those where a genetic difference could be exploited, such as oncology, obstetrics or solid-organ transplantation. In cancer patients, researchers isolated circulating free DNA characterised by mutations specific to particular malignancies[41-43]. This gave rise to the notion of a ‘‘liquid biopsy’‘ for diagnostic and management purposes[44-47]. Similarly, in the plasma of pregnant women, researchers detected fragments of DNA unique to the foetus[28], and subsequently analysed these for genetic conditions[48]. Today, ‘‘noninvasive pre-natal testing’‘ has replaced the need for chorionic villus sampling with a simple blood test[49], which is commercially available throughout the world[50]. In solidorgan transplantation, genetic differences become fundamentally intertwined. With the exception of an identical twin donor-recipient pair, this procedure places a unique genome within the recipient–theoretically creating the ideal environment for detecting circulating free donor DNAviaminimally-invasive blood sampling. Moreover, this biomarker could plausibly reflect graft integrity at low levels, and cellular death when elevated. A particular focus has emerged regarding the dynamics of this DNA during rejection, given it is this element of solid-organ transplantation that currently necessitates invasive biopsies. This is particularly the case in LT, where routine biopsies are considered controversial–and often only performed if clinically indicated[51,52]. Clearly, a liquid biopsy could be revolutionary in this setting.

Methods of detection

In order to critically appraise studies examining the clinically utility of donor-specific cell-free DNA in LT, it is important to understand the scientific advancements that have enhanced its detection.

Y-chromosome specific sequences

The first group to detect circulating free donor DNA in transplant recipient plasma were Loet al[53]in 1998. In their landmark study, they isolated fragments of donor DNA in the plasma of 36 liver or kidney transplant recipients–including six females who had received livers from male donors. In this subset of participants, the authors isolated genetic sequences unique to the Y-chromosome, which they amplified using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and visualised using gel electrophoresis. In so doing, they provided ground-breaking data proving the concept of donor-specific cell-free DNA, depicted in Figure 1. However, this methodology was limited to male-to-female engraftments only–just as a subsequent Rhesus (Rh) gene quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay was restricted to positive-to-negative transplantations[54]. As such, a focus on identifying other genetic targets that differed more broadly between individuals subsequently emerged.

Next generation sequencing

The following decade, the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) completely revolutionised gene discovery. By enabling massive genetic throughputs[55], multiple genetic loci that were highly heterogeneous within the population could now be identified. The most common of these were ‘‘single nucleotide polymorphisms’‘ (SNPs)–where DNA sequences differed by one adenine, thymine, guanine or cytosine molecule between individuals[56]. By using NGS to analyse multiple SNPs, researchers could now detect genetic sequences likely to differ between the vast majority of donorrecipient pairs. The first group to achieve this were Snyderet al[57]in 2011, who analysed blood samples from heart transplant donors and recipients, and detected circulating free donor DNA using a genome-wide SNP assay[57]. Since then, three other groups have published more targeted NGS methodology in this field[58-60], two of which circumvented this need for baseline donor blood sampling by using computational techniques[59,60]. However, in clinical practice, NGS assays have several key limitations. Not only are they highly complex and expensive, but they can take up to seven days to process[57]–rendering them potentially futile as a real-time transplantation biomarker.

Figure 1 The concept of donor-specific cell-free DNA in liver transplantation.

Droplet-digital polymerase chain reaction

Given this, an interest in developing more accessible, affordable and rapid assays arose. This coincided with the commercial availability of droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), which had a six hour turnaround time, and could more precisely quantify DNA than previous qPCR techniques[61]. Researchers began designing new ddPCR probes and primers to detect donor-specific sequences. Y-chromosome and SNP targets were revisited, but new sites included regions of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) gene and ‘‘deletion insertion polymorphisms’‘ (DIPs). At a population level, HLA genes are characterised by high levels of heterogeneity[62]. However, as donor-recipient pairs are often HLA ‘‘matched’‘[63], this target is potentially problematic in transplantation. DIPs, conversely, remain a promising option–as these are regions of the genome characterised by the absence or presence of certain nucleotides, leading to common allelic differences between individuals[64]. Ultimately, understanding these methodologies highlights the relative complexity of genetic tests, compared to more standard biochemistry such as LFTs[65]. Accordingly, each assay for circulating free donor DNA requires validation, in order to establish its utility in the clinical setting.

STUDIES IN LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

Publications to date

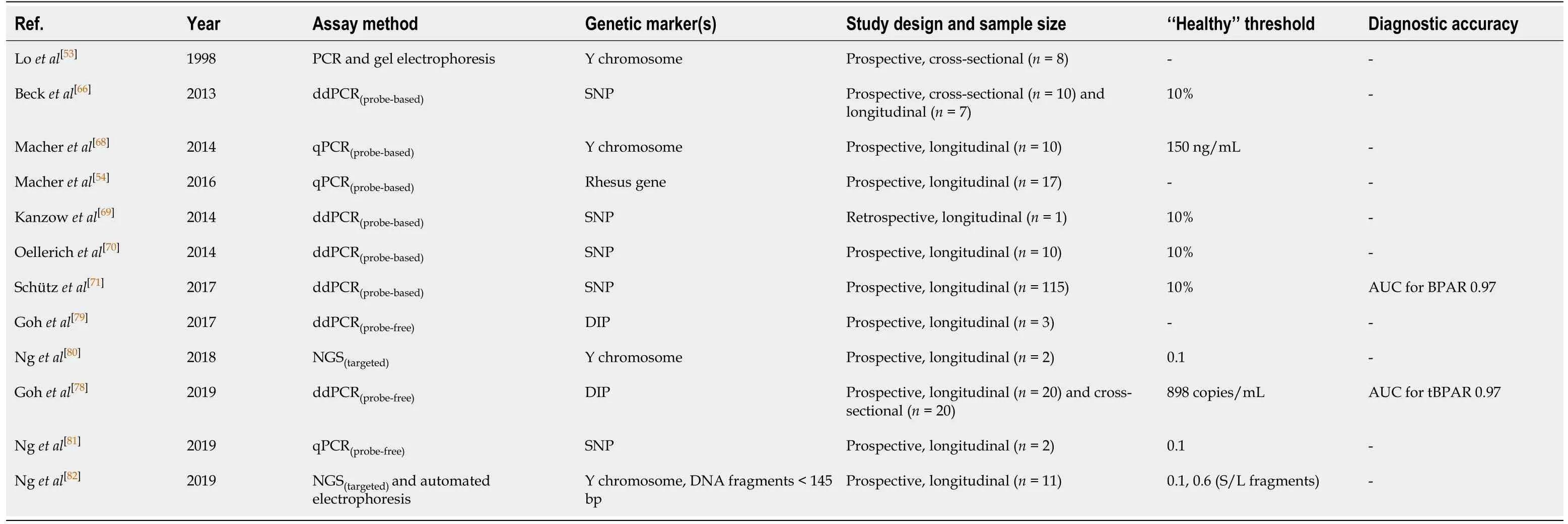

A total of 12 publications have studied donor-specific cell-free DNA in LT, as summarised in Table 1. These studies differ in their size (n= 1-115), design and assay methodologies. However, they all demonstrate that this biomarker shows promise in monitoring graft health and detecting injury–especially when caused by acute rejection.

Fifteen years after Loet al[53]first demonstrated the presence of Y-specific donor DNA fragments in LT recipient plasma, Becket al[66]went on to establish three additional key findings. In their 2013 study, they used probe-based ddPCR to scrutinise a panel of 40 SNPs and detect donor-specific sequences in 10 newly transplanted and seven stable LT recipients. These fragments of donor DNA were then quantified in terms of relative abundance and expressed as a percentage of total cellfree DNA. Firstly, Becket al[66]observed high levels of circulating free donor DNA post-engraftment (approximately 90%), which fell exponentially and stabilised within 10 d in recipients without complications. Secondly, this DNA was elevated (> 60%) in two newly transplanted patients with biopsy-proven acute rejection (BPAR), yet not inanother with obstructive cholestasis. Notably, this DNA began to increase several days prior to LFTs in those cases with rejection. Thirdly, the authors identified a ‘‘healthy’‘ threshold of donor-specific cell-free DNA of < 10% in the stable LT recipients. Additional benefits of this assay included its same-day turnaround and lack of a need for donor blood sampling. However, its limitations included the use of PCR preamplification and post-PCR handling, which can introduce several forms of bias and pose a high contamination risk, respectively[67].

Table 1 Publications examining donor-specific cell-free DNA in liver transplantation recipients (prior to census data of July 1st, 2020)

The next year, Macheret al[68]published a longitudinal study using qPCR to detect Y-specific DNA fragments in 10 gender-mismatched LT recipients.As with Becket al[66], the authors also found that this circulating free donor DNA was elevated immediately post-LT, then rapidly decreased in recipients without complications and remained stable[68]. Macheret al[68]also identified a threshold reflective of organ health–however as their assay was one of absolute quantification, this was expressed as 150 ng/mL. The authors made the novel observation that these fragments of donor DNA were also elevated in recipients who experienced cholangitis and vascular complications. Unfortunately, this study proved too small to examine the dynamics of this DNA in acute rejection, as no patients experienced this endpoint. As such, Macheret al[54]subsequently published an additional study in 2016. This time, they measured circulating free donor DNA by using qPCR to detect Rh-positive sequences in 17 Rhmismatched LT recipients. Here, in the patients who experienced BPAR, levels of donor-specific cell-free DNA were found to rise compared to those without complications. However, as these two qPCR assays targeted restrictive genetic differences only, they intrinsically had limited clinical utility.

Between 2014 and 2017, the Beck group published three additional studies using their more expansive SNP methodology[69-71]. The first of these was a case study, which described a LT recipient of a marginal graft, who had experienced multiple complications post-operatively–and retrospectively undergone donor-specific cell-free DNA analysis[69]. Kanzowet al[69]demonstrated that levels rapidly became elevated in the following settings: BPAR, traumatic liver haematoma and cytomegalovirus infection. They also made the pioneering observation that circulating free donor DNA subsequently fell post successful treatment of each complication. The authors concluded that this biomarker was useful for monitoring organ health.

Next, Oellerichet al[70]prospectively measured circulating free donor DNA and CNI levels in 10 receipts during the first month post-LT. They aimed to identify the minimum trough tacrolimus concentration that was associated with graft integrity. Using the pre-established healthy threshold of < 10%, the authors observed significant segregation and determined the lower limit of the therapeutic tacrolimus range to be 8 ug/L. Although larger studies with longer follow up were still needed, Oellerichet al[70]postulated the assay could be useful in monitoring for graft injury in LT recipients whose immunosuppression was being weaned.

This unmet need was addressed by the third study, published by Schützet al[71]In their multicentre prospective trial, donor-specific cell-free DNA was measured in 115 LT recipients at seven timepoints during the first year post-LT, plus whenever rejection was suspected. The stereotypic exponential fall of this DNA was seen in 88 stable recipients, who had a median level of 3.3%. In 17 recipients with BPAR, median levels were elevated at 29.6%. Moreover, this circulating free donor DNA was found to be an accurate and early marker of BPAR–with a superior area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.97 compared to LFTs (0.83-0.96), and levels increasing up to two weeks prior to diagnosis on liver biopsy. In patients with infective complications, median donor-specific cell-free DNA was slightly higher than in stable recipients, but lower than in BPAR (5.3%-5.7%) – similar to patterns seen by other authors[68,69]. In patients with cholestasis alone, levels remained < 10%[71]. On multivariate logistic regression, Schützet al[71]found that this biomarker provided independent information regarding graft integrity.

Whilst the benefits of the Becket al[72]assay they utilised prevailed, there were several limitations to this study[71]. These were highlighted by two cases, where patients had BPAR, but circulating free donor DNA levels remained < 10%. In the first patient, who had a marked leukocytosis, Schützet al[71]acknowledged that this factor may have ‘‘masked’‘ the percentage of cell-free DNA from the donor present in recipient plasma, due to an increase in the denominator of total cell-free DNA. Indeed, expressing circulating free donor DNA in terms of relative abundance renders it innately susceptible to this form of error–including in other circumstances where cellfree DNA increases such as infection[73], obesity[74]and exercise[75]. In the second patient with BPAR but circulating free donor DNA below the ‘‘healthy’‘ threshold, the authors attributed this to the fact that the rejection was only mild histologically, with a rejection activity index (RAI) of 1/9, and did not require treatment[71]. This case demonstrates the limited clinical utility of BPAR as an endpoint–compared to treated BPAR (tBPAR) of RAI ≥ 3, which is now widely utilised in clinical trials[76,77].

These limitations, however, were not present in the Gohet al[78]publication from 2019. This group originally validated their probe-free ddPCR assay in 2017, when they successfully targeted a panel of nine DIPs and achieved absolute quantification of circulating free donor DNA in three LT recipients[79]. Two years later, they used this technique to examine 40 recipients divided into two cohorts[78]: Longitudinal (n= 20), who had donor-specific cell-free DNA measured at five timepoints during the first six weeks post-LT; and cross-sectional, who were either undergoing a liver biopsy at least one-month post-LT (n= 16), or stable and at least one-year post-LT (n= 4). The authors demonstrated findings in keeping with the aforementioned literature. In the longitudinal group, levels of circulating free donor DNA fell exponentially and stabilised in the 14 recipients without complications. Elevated levels of this DNA were observed in three recipients with tBPAR, but not in three with cholestasis alone. In the cross-sectional cohort, elevated levels of this DNA accurately identified six patients with tBPAR, with an AUC of 0.97 that was again superior to LFTs. A healthy threshold of < 898 copies/mL was identified in the 14 cross-sectional patients without rejection and found to be reliable in the longitudinal cohort from day 14 post-LT onward. By using primer sets to hybridize across allelic breakpoints, Gohet al[78]had also eliminated the need for costly florescent probes. However, the assay called for a donor blood sample for optimal processing and the study was ultimately underpowered.

Most recently, Nget al[80-82]pioneered the measurement of circulating free donor DNA in live donor LT (LDLT). These authors utilised different assays to detect the relative abundance of this DNA in paediatric recipients from day 0-60 post-LDLT. First, NGS was used to detect Y-specific sequences in two gender-mismatched LDLTs96. Next, a qPCR SNP assay was examined in two additional LDLT recipients97. In both publications, Nget al[82]found that circulating free donor DNA exponentially fell and stabilised at < 0.1, as seen with the Becket al[66]group. Finally, the initial NGS Y-specific assay was used in 7 gender-mismatched LDLTs to detect circulating free donor DNA, which was then profiled according to its fragment size[82]. Here, the authors made the innovative observation that donor DNA fragments were ‘‘short’‘ (105-145 bp), compared to the ‘‘long’‘ fragments of recipient DNA (> 160-170 bp). NGS and automated electrophoresis was then used to detect these short donor DNA fragments in four gender-matched LDLT recipients. The authors also noted that the ratio of short to long (S/L) fragments correlated with the circulating free donor DNA levels–and identified a healthy S/L fragment threshold of < 0.6. Interestingly, in the oncology and obstetric research settings, the fragments of DNA from tumour cells or from the foetus are also shorter (i.e.than those from non-malignant or maternal cells respectively) but the mechanism behind this is unclear[83,84]. Certainly, this Nget al[80-82]fragment size-based assay was quicker and less restrictive than targeting the Ychromosome. However, its methodology was still slower (24 h) and more expensive than PCR. Furthermore, these three studies were limited by their small sample size of uneventful LDLTs[80-82]–precluding insights into the dynamics of their assays during complications.

DISCUSSION

In summary, these studies show that donor-specific cell-free DNA is a biomarker with promising clinical utility in LT. It consistently demonstrates stereotypic dynamics in states of graft health[54,66,68,71,78]. As such, it could be used to rule out organ injury as part of a diagnostic workup post-LT. In the setting of acute rejection, circulating free donor DNA repeatedly outperforms LFTs in terms of both its discriminatory and timely detection of this LT complication[71]. Given this, it could be used to prompt early adjustments to therapy if rising in the setting of an immunosuppression wean–potentially preventing an episode of tBPAR. It could also be used to avoid a liver biopsy when present at low levels, enabling clinicians to observe recipients or investigate less invasively knowing tBPAR is highly unlikely. Ultimately, further studies are required to fully establish the potential of donor-specific cell-free DNA as a ‘‘liquid biopsy’‘ in LT. In particular, a focus on identifying thresholds diagnostic of acute rejection, or reflective of its effective treatment, would be of high clinical value.

Reflecting on the biology underlying these results also yields further insights. Firstly, the researchers who discovered that circulating free donor DNA was more sensitive and specific for acute rejection than LFTs have postulated as to why this is the case[71,78]. Both Schützet al[71]and Gohet al[78]concluded that, compared to LFTs, elevated levels of this novel biomarker reflect a relatively simple process–that of donor organ cellular death, releasing DNA into the recipient circulation. Conversely, bilirubin and the liver enzymes can rise due to a number of complex pathways. Secondly, other researchers have shown that levels of circulating free donor DNA also rise in infective and vascular complications post-LT[68,69,71]. Whilst these are also potential causes of graft cell death, other studies have indicated that inflammatory states might affect cell-free DNA levels[85]. Therefore, as a potential biomarker, these donor-specific assays need to be carefully interpreted by expert clinicians within the clinical context. Finally, in contrast to LFTs, circulating free donor DNA levels were noted in several studies to remain stable in the setting of cholestasis alone[66,71,78]. Whilst the reasons for this remain unclear, potential explanations could include the different vasculature of the biliary tree compared to hepatocytes, or its drainage system into the duodenum.

Additional issues that have been addressed include the impact of ‘‘blood microchimerism’‘ from donor leukocytes, or of blood transfusions from other/pooled donors. In their landmark study, Loet al[53]did not detect any haematopoietic donor cells in the recipients’ circulation. Subsequently, Schützet al[71]analysed a subset of 12 patients, and found donor leukocytes were either absent or barely present (0%-0.068%). Both authors therefore concluded that blood microchimerism could be excluded as a confounding source of circulating free donor DNA[53,71]. Conversely, an additional case report by Gohet al[86]found that their assay was affected by blood transfusions. In this LT recipient, with no other evidence of graft injury, donor-specific cell-free DNA rapidly rose and fell post receiving fresh frozen plasma (FFP). As such, the authors suspected the FFP had temporarily confounded their results. However, given the short half-life of unencapsulated DNA, this could potentially be controlled for by performing assays for circulating free donor DNA several hours post such transfusions.

Ultimately, these LT studies represent just one aspect of the broader donor-specific cell-free DNA literature. In a recent systematic review, Knightet al[25]identified 47 studies examining this biomarker in solid-organ transplantation (census date June 2018). Most were in kidney (38.3%) or heart (23.4%) transplant recipients, and a smaller number were from the lung (10.6%) and kidney-pancreas (2.1%) setting. As with the LT literature, these studies varied in their design, size (n= 1-384) and assay methodologies. In five studies, the same assay was validated across multiple organs. In their narrative analysis, the reviewers found comparable results across multiple organs–with a few specific nuances. In all 21 studies that examined newly transplanted patients, circulating free donor DNA fell and stabilised by day 10. However, liver and lung recipients had higher baseline mean levels (2%-5%) than kidney and heart recipients (0.06%-1.2%)–potentially due to their larger graft size. Of the 41 studies that examined this biomarker in acute rejection, the vast majority observed levels to increase (97.5%), yet less than half reported diagnostic accuracy data (46.3%). Interestingly, of all organs studied, circulating free donor DNA rose to higher thresholds and with greater accuracy for BPAR in LT. Whilst no studies identified thresholds diagnostic of BPAR, several noted that levels returned to baseline post successful treatment. Overall, Knightet al[25]concluded that donor-specific cell-free DNA was a valid biomarker in all organ types.

Since then, the literature has continued to rapidly evolve. At the time of writing, more than 25 additional studies examining circulating free donor DNA had been published–including several from large cohorts of kidney (n= 107-189)[87,88], heart (n= 241-773)[89,90]and lung (n= 106)[91]transplant recipients. Additional developments have included the publication of new guidelines regarding optimal laboratory processing of cell-free DNA[92]. There has also been an emerging interest in other cell-free genetic targets, such as hepatocyte-specific methylation markers[93,94], and mitochondriaderived DNA (mDNA)[95,96]. Finally, some of these studies have led to the commercialisation of particular dsfDNA assays. AlloSure®and AlloMap®(CareDx, Inc., Brisbane CA) have been validated in large cohorts of kidney and heart transplants recipients respectively[89,97-99]. Prospera®(Natera, Inc., San Carlos CA) has also been validated in a renal transplant study[100]. Yet, as these three assays are all NGS-based, their routine use in clinical practice remains problematic. More recently, myTAIHEART®(TAI Diagnostics, Inc., Wauwatosa WI), which targets SNPs with qPCR to quantify circulating free donor DNA in relative abundance, was validated in heart transplant recipients[89,90]. However, as baseline thresholds and diagnostic accuracy of these assays can differ across organ types, they require further validation prior to their potential use in LT.

CONCLUSION

Given the rising number of LT recipients who require long-term monitoring[2,3], further donor-specific cell-free DNA research in this field could be of high clinical impact. Currently, there are two large prospective trials underway further examining AlloSure®in kidney transplantation (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03326076), and its use in conjunction with AlloMap®in heart transplantation (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03695601). Clearly, the commercialisation and larger scale analysis of circulating free donor DNA in LT is also required. Following this, next steps should include a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing standard of care post-LT to precision medicine additionally guided by changes in donor-specific cell-free DNA levels. Ideally, this RCT should also include a comparative cost analysis of these two models of care. Lastly, LT studies combining this biomarker with other novel tests would be particularly impactful–such as those quantifying immune function[77], or machine learning algorithms[26]. Ultimately, the use of innovative tools in an integrated manner could enable clinicians to continue the legacy of exceptional progress and further improve patient outcomes post-LT.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Simon Cockroft for creating the image used in Figure 1, and to Dr Bruce McClure for his diligent proofreading.

World Journal of Transplantation2020年11期

World Journal of Transplantation2020年11期

- World Journal of Transplantation的其它文章

- Torque teno virus in liver diseases and after liver transplantation

- Lenvatinib as first-line therapy for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: Is the current evidence applicable to these patients?

- Obstetrical and gynecologic challenges in the liver transplant patient

- Extracellular vesicles as mediators of alloimmunity and their therapeutic potential in liver transplantation

- Intraoperative thromboelastography as a tool to predict postoperative thrombosis during liver transplantation

- Exploring the safety and efficacy of adding ketoconazole to tacrolimus in pediatric renal transplant immunosuppression