Anticoagulation in simultaneous pancreas kidney transplantation-On what basis?

Jeevan Prakash Gopal,Frank JMF Dor,Jeremy S Crane,Paul E Herbert,Vassilios E Papalois,Anand SR Muthusamy

Abstract BACKGROUND Despite technical refinements,early pancreas graft loss due to thrombosis continues to occur.Conventional coagulation tests (CCT) do not detect hypercoagulability and hence the hypercoagulable state due to diabetes is left untreated.Thromboelastogram (TEG) is an in-vitro diagnostic test which is used in liver transplantation,and in various intensive care settings to guide anticoagulation.TEG is better than CCT because it is dynamic and provides a global hemostatic profile including fibrinolysis. AIM To compare the outcomes between TEG and CCT (prothrombin time,activated partial thromboplastin time and international normalized ratio) directed anticoagulation in simultaneous pancreas and kidney (SPK) transplant recipients. METHODS A single center retrospective analysis comparing the outcomes between TEG and CCT-directed anticoagulation in SPK recipients,who were matched for donor age and graft type (donors after brainstem death and donors after circulatory death).Anticoagulation consisted of intravenous (IV) heparin titrated up to a maximum of 500 IU/h based on CCT in conjunction with various clinical parameters or directed by TEG results.Graft loss due to thrombosis,anticoagulation related bleeding,radiological incidence of partial thrombi in the pancreas graft,thrombus resolution rate after anticoagulation dose escalation,length of the hospital stays and,1-year pancreas and kidney graft survival between the two groups were compared. RESULTS Seventeen patients who received TEG-directed anticoagulation were compared against 51 contemporaneous SPK recipients (ratio of 1:3) who were anticoagulated based on CCT.No graft losses occurred in the TEG group,whereas 11 grafts (7 pancreases and 4 kidneys) were lost due to thrombosis in the CCT group (P = 0.06,Fisher’s exact test).The overall incidence of anticoagulation related bleeding (hematoma/ gastrointestinal bleeding/ hematuria/ nose bleeding/ re-exploration for bleeding/ post-operative blood transfusion) was 17.65% in the TEG group and 45.10% in the CCT group (P = 0.05,Fisher’s exact test).The incidence of radiologically confirmed partial thrombus in pancreas allograft was 41.18% in the TEG and 25.50% in the CCT group (P = 0.23,Fisher’s exact test).All recipients with partial thrombi detected in computed tomography(CT) scan had an anticoagulation dose escalation.The thrombus resolution rates in subsequent scan were 85.71% and 63.64% in the TEG group vs the CCT group (P = 0.59,Fisher’s exact test).The TEG group had reduced blood product usage {10 packed red blood cell (PRBC) and 2 fresh frozen plasma (FFP)} compared to the CCT group (71 PRBC/ 10 FFP/ 2 cryoprecipitate and 2 platelets).The proportion of patients requiring transfusion in the TEG group was 17.65% vs 39.25% in the CCT group (P = 0.14,Fisher’s exact test).The median length of hospital stay was 18 days in the TEG group vs 31 days in the CCT group (P = 0.03,Mann Whitney test).The 1-year pancreas graft survival was 100% in the TEG group vs 82.35% in the CCT group (P = 0.07,log rank test) and,the 1-year kidney graft survival was 100% in the TEG group vs 92.15% in the CCT group (P = 0.23,log tank test). CONCLUSION TEG is a promising tool in guiding judicious use of anticoagulation with concomitant prevention of graft loss due to thrombosis,and reduces the length of hospital stay.

Key words:Anticoagulation;Pancreas transplantation;Thromboelastography;Thrombosis;Hypercoagulability

INTRODUCTION

In spite of technical refinements,pancreas allograft thrombosis remains the most common non-immunological cause of early graft loss in pancreas transplantation[1,2].The exact incidence of pancreas graft loss due to thrombosis varies between 1 and 40%,but has been reported to be as high as 29% in the first 6 months after transplantation[3,4].The etiology is multifactorial encompassing donor and recipient factors.In contrast to other forms of solid organ transplantation,a hypercoagulable state due to diabetes and alteration in the venous flow dynamics (in a low flow organ)leading to stasis are additional risk factors for thrombosis inherent for pancreas transplantation.In this context,most of the centers have adopted routine prophylactic anticoagulation.Majority of the centers anticoagulate their recipients based on conventional coagulation test (CCT) and only fewer centers utilize point of care (POC)testing like TEG (Thromboelastography)/ ROTEM (Rotational thromboelastometry) to optimize anticoagulation.The existing literature about TEG in pancreas transplantation has suggested that perioperative TEG can identify high risk recipients at risk of graft thrombosis and also has presented the argument for individualized anticoagulation[3,5].So far,there is no clear consensus on the basis for anticoagulation and to the best of our knowledge no one has attempted to compare the outcomes between TEG and CCT-directed anticoagulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Following institutional audit committee approval,a retrospective analysis of 127 pancreas transplants performed between 2008 and 2019 was done.Data was collected from a prospectively maintained database.After excluding isolated pancreas transplants (Pancreas after kidney and pancreas transplant alone),re-transplants,recipients with a known thrombophilic disorder and,grafts from pediatric donors,sixty-eight SPK transplant recipients were included in the study.The recipients in both the groups were matched for donor age and graft type [donors after brainstem death(DBD)/donors after circulatory death (DCD)].

Donor selection criteria

According to our center’s protocol,all the DBD donors were less than 65-years old and all the DCD donors were less than 55-years old.The body mass index (BMI) cut off was 30 kg/m2.All the DCD donors had a functional warm ischemia time (systolic blood pressure <50 mmHg and/or oxygen saturation of 70%) of less than 60 min and the downtime of less than 30 min.

Operation technique and immunosuppression

All of the recipients had a standard arterial reconstruction using the donor iliac artery bifurcation (Y graft) anastomosed to the splenic and superior mesenteric artery (SMA).Portal vein extension was used on an individual case basis.University of Wisconsin solution was used for organ preservation.Pancreas graft was implanted on the right side either extra-peritoneally (74.50%) into the common or external iliac vessels or intra-peritoneally (25.50%) with inflow from the common iliac artery and venous drainage to the inferior vena cava.All of the kidneys were implanted into the external iliac vessels on the contralateral side except for one,which was implanted on the same side.The choice of implantation was based on clinical consideration and surgeon’s preference.All of the recipients had enteric exocrine drainage.Immunosuppression consisted of induction with intravenous alemtuzumab 30 mgs (single dose) and methylprednisolone 500 mgs.Maintenance immunosuppression was with tacrolimus,mycophenolate mofetil and a short course of steroids (7 days).

Thromboelastogram

Thromboelastogram (TEG) was developed by Dr Helmut Hartert[6]in 1948 and is being used extensively in trauma,cardiac surgery and liver transplantation[7-9].TEG HaemoneticsRis anin-vitrodiagnostic test in which a plastic pin attached to a torsion wire is immersed into a small cuvette of blood and the cuvette is rotated through an arc of approximately 4.75 degrees,6 times per minute to simulate sluggish flow and to activate coagulation.The kinetic changes transmitted by the torsion wire is analyzed by the analyzer.The variables of interest are:reaction time (R,measured in seconds)the time from the start of the test until initiation of fibrin formation;clot kinetics (K,measured in seconds) time from R until clot reaches 20mm;angle (α) angle from the tangential line drawn to meet the TEG tracing from R;maximum amplitude (MA,measured in mm) a reflection of clot strength and coagulation index (CI,measured in dynes/second) which is a culmination of all the above parameters.The R time indicates the concentration of soluble clotting factors in plasma and correlates with prothrombin time (PT) results.The K correlates positively with PT/ activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) results and inversely with fibrinogen levels.The angle (α)indicates the rapidity of fibrin build up and cross-linking,and is a dynamic measure that is unique to thromboelastography.The α and MA correlates positively with fibrinogen and platelet levels in circulation;high fibrinogen levels or thrombocytosis results in increased α and MA.

TEG protocol

TEG was done at the following time points:at the time of anesthetic induction;before clamping of vessels;on return to anesthesia recovery;twice daily for the first 48 hours;24 hours after any major alteration in anticoagulation dose;repeated as and when required until discharge.Kaolin tracing was used for clinical decision making.The target CI was between-3 and +3.

Anticoagulation protocol

Prophylactic anticoagulation consisted of intravenous heparin initially started at 100 IU/hour once clinically stable and titrated up to a maximum of 500 IU/hour directed by TEG results in the TEG group/ by a combination of clinical and laboratory parameters in the CCT group (presence or absence of hematuria,character and quantity of drain output,hemoglobin and platelet trend and,aPTT results).Intravenous heparin was subsequently switched to subcutaneous heparin 2500 or 5000 IU twice daily and then to Enoxaparin 20 mgs once daily/ Tinzaparin 3500 IU once daily at discharge.Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was continued until 6 weeks post-transplant.After 6 weeks LMWH was stopped and Aspirin 75 mgs once daily was continued indefinitely.

Therapeutic anticoagulation consisted of either enoxaparin 1.5 mgs/kg body weight or tinzaparin 175 IU/kg body weight or warfarin dosing adjusted to aim for an international normalized ratio between 2 and 2.5,andcontinued for three months.

Definition of bleeding

Post-operative blood or blood component transfusion,gross and significant hematuria,upper or lower gastrointestinal bleeding,intracranial bleeding,nose bleeding,bleeding or hematoma in the injection sites,hematoma identified in computed tomography (CT) scan and re-exploration where no source of bleeding was identified were considered anticoagulation related bleeding.

Intraoperative blood product usage and re-explorations where specific bleeding source was identified were considered surgical bleeding and excluded.Bleeding after initiation of therapeutic dose of anticoagulation was excluded.

Indications for CT scan

A triple phase contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was done for the following indications:Sudden onset of severe abdominal pain;consistently increasing amylase;new onset hyperglycemia after a period of insulin independence;concerns regarding perfusion in the ultrasound scan.All the CT scans were interpreted by two independent radiologists and finally reported.

Outcome parameters studied

Pancreas and kidney graft loss due to thrombosis,incidence of anticoagulation related bleeding,blood and blood product usage,proportion of patients requiring transfusion,radiological incidence of partial thrombus,thrombus resolution rate after anticoagulation dose escalation and length of hospital stay were compared between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (%) and continuous variables as median.Difference between the categorical variables were assessed by using Fisher’s exact test and difference between the continuous variables were assessed by using Mann Whitney test.Survival analysis was done by using Kaplan-Meir survival plots.All the statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (Version 8).

RESULTS

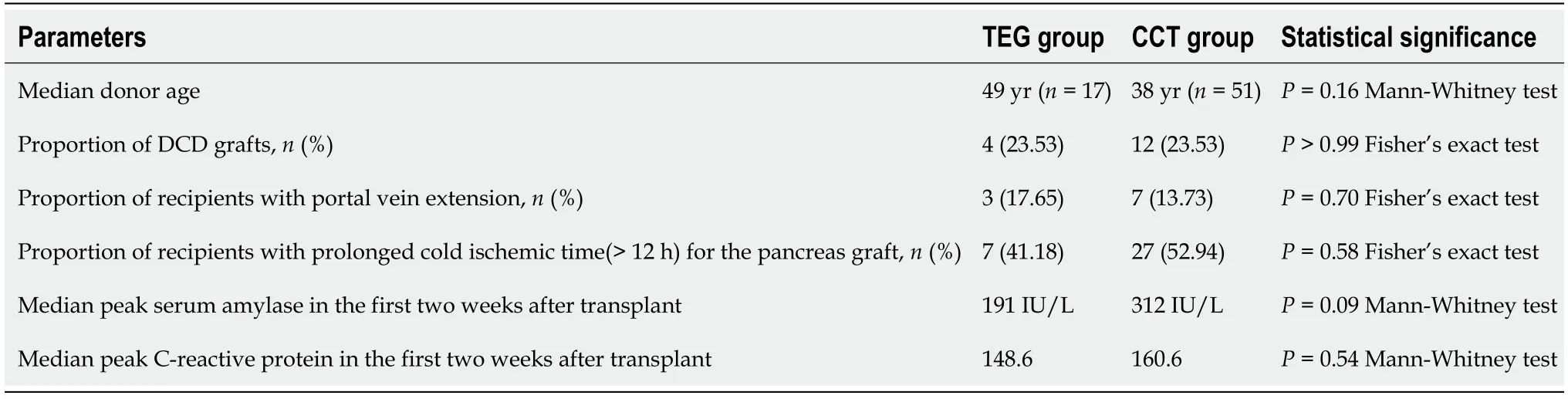

Seventeen SPK recipients received TEG-directed anticoagulation and were compared against 51 contemporaneous SPK recipients who were anticoagulated based on CCT.The two groups were comparable in terms of risk factors for graft thrombosis(Table 1).The peak value of serum amylase and C-reactive protein within the first week after transplantation,and prolonged cold ischemia time for the pancreas (more than 12 hours) were utilized as surrogate markers for graft pancreatitis.

Table 1 Comparison of risk factors for graft thrombosis

Thrombotic graft loss

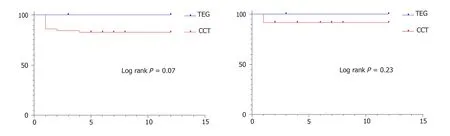

There was no thrombotic graft loss in the TEG group whereas 10.78% of grafts (7 Pancreases and 4 kidneys) were lost due to thrombus in the CCT group (P =0.06,Fisher’s exact test).Out of the 11 grafts that were lost,7 were explanted on table (4 pancreases and 3 kidneys) and the rest of them were explanted within the first week after transplant.2 of them were from DCD donors and the rest of the 9 grafts were from DBD donors.As depicted in Figure 1,the one-year pancreas graft survival was 100% in the TEG groupvs82.35% in the CCT group (P =0.07,Log-rank test) and the one-year kidney graft survival was 100% in the TEG groupvs92.15% in the CCT group(P =0.23,log rank test).

Anticoagulation related bleeding

The incidence of anticoagulation related bleeding was 17.65% (3/17) in the TEG groupvs45.10% (23/51) in the CCT group (P =0.05,Fisher’s exact test).Two patients in TEG group and 4 patients in the CCT group required re-exploration and no source of bleeding was identified.In the CCT group 8 patients had hematoma (peri-nephric-4/peri-pancreatic-4) identified in the CT scan,one patient had significant hematuria,one patient had GI bleeding and 9 patients required blood transfusion;whereas 1 patient in the TEG group had peri-nephric hematoma.

The overall blood product usage was 12 in TEG group {10 packed red blood cells(PRBC) and 2 fresh frozen plasma (FFP)}vs85 in the CCT group (71 PRBC/ 10 Cryoprecipitate/ 2 FFP and 2 platelet).

Transfusion requirement

The proportion of patients requiring transfusion in TEG group was 17.65%vs39.25%in the CCT group (P =0.14,Fisher’s exact test).

Radiological incidence of partial thrombus

The radiological incidence of partial thrombus in the pancreas graft vasculature in TEG group was 41.18% (7/17)vs25.50% (13/51) in CCT group (P =0.23,Fisher’s exact test).The non-occlusive thrombi were identified in the distal splenic artery (n= 7,4 in the TEG groupvs3 in the CCT group);in distal splenic vein (n= 2,2 in the CCT group);in both the distal splenic artery and splenic vein (n= 6,1 in the TEG groupvs5 in the CCT group);in the SMA (n= 1,1 in the CCT group);in the distal splenic artery and SMA (n= 2,2 in the TEG group) and in the graft portal vein (n= 3,1 in the TEG groupvs2 in the CCT group).In the TEG group 2/7 grafts with partial thrombi were from DCD donors while 4/13 grafts with partial thrombi in the CCT group were from DCD donors.All the patients with partial thrombus in TEG group had a kaolin coagulation index (CI) of more than +3 in the intraoperative TEG,indicating a hypercoagulable state.The indications for CT scan were hyperglycemia (n =5),hyperamylasemia (n =9),severe abdomen pain (n =3),hemoglobin drop (n =2),recurrent hypoglycemia(n =1),and reduced flow in doppler (n =1)

Thrombus resolution

Among the patients with partial thrombus,all patients had anticoagulation dose escalation in the TEG group while 9/11 patients had anticoagulation dose escalation in the CCT group and the remaining 2 patients in the CCT group received therapeutic dose of anticoagulation for 3 months due to associated iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis.The thrombus resolution rate after anticoagulation dose escalation was 85.71% (6/7) in TEG groupvs63.64% (7/11) in the CCT group (P =0.59,fisher’s exact test).All 5 patients with persistent thrombus had functioning pancreas allografts.

Figure 1 Graft survival.

Length of hospital stay

The median length of hospital stay was 18 days in TEG groupvs31 days in CCT group(P =0.03,Mann Whitney test).

DISCUSSION

Graft thrombosis is still the most common non-immunological cause for early graft loss in pancreas transplantation and the etiology is multifactorial.Anticoagulation is the key solution to prevent graft thrombosis.Although CCT are widely available to guide anticoagulation,they are time consuming and don’t reliably measure hypercoagulability and fibrinolysis.Moreover,these tests are done using plasma rather than whole blood and hence the contribution of platelets towards clot formation and clot strength is not measured.

The thromboelastography is anin-vitroassessment of the thrombodynamic properties of blood as it is induced to clot under a low shear environment,aimed to resemble sluggish venous flow.TEG is a dynamic and real-time measure of coagulation and is more accurate than CCT as it provides a comprehensive hemostatic profile including fibrinolysis.The results of TEG are available much faster than CCT.Titrating anticoagulation in the early post-operative period is very crucial in pancreas transplantation and the rapid accessibility and reproducibility of TEG makes it more suitable than CCT to drive anticoagulation.

The case series by Vaidyaet al[5]has already reported that TEG serves to identify the cohort of patients at risk for graft thrombosis and thereby enabling safe therapeutic anticoagulation with minimum morbidity and mortality.For the first time,we have compared CCTvsTEG-directed anticoagulation in pancreas transplantation and have re-iterated the advantages of TEG-directed anticoagulation.Although the difference in the percentage of graft loss between the two groups was not statistically significant,in our view,the two groups were comparable in terms of risk factors for graft thrombosis and no thrombotic graft loss in the TEG group in this setting has a definite clinical impact while a greater number of patients are needed to achieve statistical significance.A pre-operative TEG identifies the subgroup of patients at higher risk of thrombotic graft loss thereby guiding judicious use of anticoagulation.The anticoagulation related bleeding was less in the TEG group as evidenced by lower rates of re-exploration,reduced blood product usage and transfusion requirements.This is because only those patients towards the hypercoagulable spectrum in the TEG(CI >+3) had higher than conventional doses of anticoagulation.The shorter length of hospital stay in the TEG group is an added advantage.The reasons for prolonged hospital admission in CCT group were,the need for re-exploration (n =8) and peripancreatic collection with infection (n =14).The delayed graft function rates were comparable between the two groups (17.65% in the TEG groupvs21.56% in the CCT group)

The other important finding in this study is that,apart from the two patients who had thrombi in the pancreas graft vasculature coexisting with iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis,none of the remaining patients with partial venous or arterial thrombi were therapeutically anticoagulated in both the groups.Irrespective of thrombus resolution,all of the patients with partial thrombi in the pancreas graft vasculature had a functioning pancreas allograft.The inference is that not all patients with partial thrombi in the pancreas allograft need therapeutic anticoagulation.The different strategies reported for the management of partial thrombi are:therapeutic anticoagulation,early re-exploration and endovascular thrombectomy and thrombolysis[10-12].In our study,16/19 patients had distal non-occlusive thrombi and hence anticoagulation dose escalation was sufficient.Even with the 3 patients who had non-occlusive thrombi in the main portal vein,anticoagulation dose escalation was adequate.Our results concur with the study published by Hakeemet al[13],although it is not supported by a CT grading system.

The optimal regimen for prophylactic anticoagulation still remains a topic of debate.The anticoagulation protocols are center specific,and is often a mix of heparin,antiplatelet agents,dextran and warfarin[3,5,14,15].Most of our recipients were on intravenous heparin in the immediate post-operative period due to the feasibility of urgent reversal in the event of bleeding and,subsequently switched to LMWH,that was continued until 6 weeks.LMWH was not commenced from the beginning as there are several studies[14,16]reporting that early post-operative use of low dose unfractionated heparin prevents early graft loss due to thrombosis without increased risk of bleeding and also due to the different pharmacokinetics of LMWH that hampers their safe usage in the early post-transplant period.The incidence of pancreas graft loss due to thrombosis in our study was 10.30% (7 patients),which is similar to that reported in other studies[3,5,14,15].Another approach would be to use platelet function assays and fibrinolysis to guide anticoagulation.Ravehet al[17]has reported a higher graft thrombosis rate (61%) in patients with pre-operative platelet dysfunction,although the thrombosis rate was not significantly different between normal and abnormal fibrinolysis phenotypes.This might help in deciding the addition or dose modification of antiplatelets in the anticoagulation regimen.With the widespread utilization of alemtuzumab for induction therapy,the associated thrombocytopenia with a reported incidence of 14%[18]and subsequent platelet reconstitution also needs to be accounted for when deciding anticoagulation and hence dynamic anticoagulation monitoring such as the TEG is crucial.

With the rising organ scarcity and shifting donor demographics,the pancreas transplant community has obviously expanded the donor acceptance criteria.This together with increasing DCD donation in many countries can potentially increase the incidence of pancreas graft thrombosis[19-21].TEG can be a promising tool that can aid to push the boundary more effectively thereby translating into more successful clinical outcomes.

The benefits of TEG-directed anticoagulation do not stop with pancreas component of the SPK.As evidenced from the study none of the kidneys in the TEG group were lost to thrombosis.Transplant renal vein thrombosis occurs early after the transplantation with a reported incidence of 0.1%-4.2% and diabetes in the recipient is one among the other risk factors for graft thrombosis[22,23].TEG-directed anticoagulation in diabetic patients needing kidney transplantation is another potential area for application.

Limitations of the study are the retrospective nature,and a relatively small number of patients.The surgical techniques for pancreas transplantation have been evolving and transplants with caval venous drainage has been reported to have lower risk of graft thrombosis predominantly due to higher blood flow in the inferior vena cava[24,25].The majority of the transplants in the TEG group were performed intraperitoneally with caval venous drainage (52.94%) compared to the CCT group (5.88%)and it could potentially be a confounding variable.This reflects a change in practice in our center due to the expanding surgical team.It is also crucial to note that none of the grafts were lost to thrombosis even in the remaining 8 recipients with iliac venous drainage in the TEG group.In our opinion,the results of this study pertaining to graft loss confirm the existing literature about TEG in pancreas transplantation and add new insights on several other benefits of TEG-directed anticoagulation.

In conclusion,this is the first study to compare the outcomes between TEG and CCT-directed anticoagulation in SPK transplantation.It is clearly evident that TEGdirected anticoagulation prevents thrombotic graft loss without concurrent increase in anticoagulation related bleeding and also reduces the length of hospital stay.Future larger studies with cost benefit analyses would be relevant for increasing the utilization of TEG in pancreas transplantation.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Pancreas allograft thrombosis is the most common non-immunological cause for early graft loss.Hence,prophylactic anticoagulation has become the routine practice.Conventional coagulation tests (CCT) are slow in titrating anticoagulation especially in the early post-operative period and also don’t detect hypercoagulable state that is inherent to diabetes and is left unaddressed.Thromboelastogram (TEG) is a dynamic,rapid and reliable tool that provides a complete picture of coagulation.TEG based anticoagulation in pancreas transplantation has been proven to identify patients at risk of thrombotic graft loss thereby enabling safe anticoagulation with least morbidity and mortality.

Research objective

Despite these studies,there is no clear consensus for the basis of anticoagulation.Therefore,we aimed to compare the outcomes between TEG and CCT based anticoagulation in simultaneous pancreas and kidney (SPK) transplantation.

Research methods

A single center retrospective analysis comparing the outcomes between TEG and CCTdirected anticoagulation in SPK recipients,who were matched for donor age and graft type (Donors after brainstem death and donors after circulatory death).Anticoagulation consisted of intravenous (IV) heparin titrated up to a maximum of 500 IU/hour based on CCT in conjunction with various clinical parameters or directed by TEG results.Graft loss due to thrombosis,anticoagulation related bleeding,radiological incidence of partial thrombi in the pancreas graft,thrombus resolution rate after anticoagulation dose escalation,length of the hospital stays and,1-year pancreas and kidney graft survival between the two groups were compared.

Research results

For the first time we have compared TEG and CCT directed anticoagulation in pancreas transplantation.There were no thrombotic graft losses in the TEG group whereas 7 pancreases and 4 kidneys were lost in the CCT group.The incidence of anticoagulation related bleeding was less (17.65% TEGvs45.10%CCT,P =0.05) and also the median length of hospital stay was reduced (18 days TEGvs31 days CCT,P =0.03) in TEG group compared to the CCT group.

Research conclusions

TEG based anticoagulation prevents thrombotic graft loss without concomitant increase in the incidence of anticoagulation related bleeding and also reduces the length of hospital stay.Hereby our findings re-confirm the published literature.

Research perspectives

Future prospective studies with more patient numbers will be more beneficial for generating a robust evidence base.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to acknowledge our nephrology and anesthesia colleagues of Imperial College Renal and Transplant Center for their contribution towards patient management.