Comparative study between bowel ultrasound and magnetic resonance enterography among Egyptian inflammatory bowel disease patients

Shimaa Kamel, Mohamed Sakr, Waleed Hamed, Mohamed Eltabbakh, Safaa Askar, Ahmed Bassuny, Rasha Hussein, Ahmed Elbaz

Abstract

Key Words: Bowel ultrasound; Colonoscopy; Crohn's disease; Magnetic resonance enterography; Ulcerative colitis; Inflammatory bowel disease

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are chronic, relapsing inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Medical imaging is decisive for diagnosis and locating the bowel lesion with its extramural extent and complications. It assesses its degree of activity, assigning patients in need for surgery and can be used for their follow-up.

Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) is one specific imaging technique for such diseases[1]. T2W and T1W images after intravenous gadolinium have high accuracy for diagnosis and assessment of disease activity[2].

Bowel ultrasound is also becoming progressively important in IBD management. Ultrasonography is a noninvasive, non-radiating, cheap, and very available technique that is acceptable and tolerated by patients and can be used repeatedly for follow-up examinations. Ultrasonography for these patients needs higher frequency linear array probes (5-15 MHz) for assessment of the five-layer wall of the bowel[3].

Up until now, no previous comparative studies between bowel ultrasound and MRE for Egyptian patients who suffered/are suffering from IBD, either ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, have been published.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Our study enrolled 40 patients who presented to our IBD center at Ain Shams University Hospital during the period from September 2017 to September 2018.

The study was approved by the medical ethics committee of Ain Shams University. The study population included adolescents who were over 18 years old. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. Patients were excluded if they had severe or uncontrolled comorbidities, such as cardio-respiratory, neurological, metabolic, liver, kidney diseases, claustrophobia, cardiac pacemaker, or implanted metal objects that prohibited use of MRE.

All patients reported a complete medical history, underwent thorough clinical examinations and laboratory investigations, including complete blood count, liver profile tests, renal profile tests, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, MRE, bowel ultrasound, and colonoscopy up to the terminal ileum with biopsies for histopathological examination.

Clinical activity score for Crohn's disease was assessed by The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI). Clinical remission was determined if CDAI was < 150 points or no fistula drainage was found as assessed by the Fistula Drainage Assessment index[4]. Ulcerative colitis activity was assessed using the Truelove and Witts classification based on clinical and laboratory parameters, such as fever, frequency of bowel movements, rectal bleeding, tachycardia, anemia, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate[5].

Colonoscopies were performed with a videoscope system from Olympus Exera II CV-180 after colonic preparation and fasting for six hours.

Bowel ultrasound

Bowel ultrasound was done by one examiner who had performed several previous general ultrasound examinations. This examiner was trained for several bowel ultrasound exams under supervision of an ultrasound gastroenterologist specialist at Sacco Hospital, Italy. Bowelultrasoundassessment was reviewedblindly comparedto MRE and colonoscopy.

Patients were examinedviaultrasound after a six-hour fasting period to minimize intestinal air contents. Examination was done by ultrasound machine (Toshiba Xario, Japan) with a low frequency curved-array transducer (2.5-4.5 MHz) to determine any pathological bowel motility or distension and any para-intestinal structures, such as abscesses, in all abdominal quadrants. Examination with a high-frequency linear-array transducer (6.0-8.4 MHz) was used for bowel wall examination starting with examination of the proximal colon followed with the distal one and then the small bowel[3]. This examination assessed criteria of inflammation such as thickness of bowel wall, inflammatory mesenteric fat and lymph nodes, hyperemia on color Doppler flow, and complications, such as stenosis, fistulas or inflammatory masses.

In the longitudinal direction, the bowel wall was measured for bowel thickness at its anterior wall or in an area in which it was more visible in order to avoid mucosal folds and haustrations. The cursor was placed at the end of the interface echo between the serosa and proper muscle to the start of the interface echo between the lumen and the mucosa[6,7].

Several criteria for stenosis diagnosisviaultrasound have been reported, such as thickened bowel wall, narrowing of the diameter of the lumen < 1 cm, hyperperistalsis of the pre-stenotic bowel, and proximal dilatation > 25-30 mm[8-10].

An abscess was indicated by bowel ultrasound as an irregular, avascular hypoechoic area with a small amount of internal echoes or air in the form of hyperechoic streaks[9].

MRE

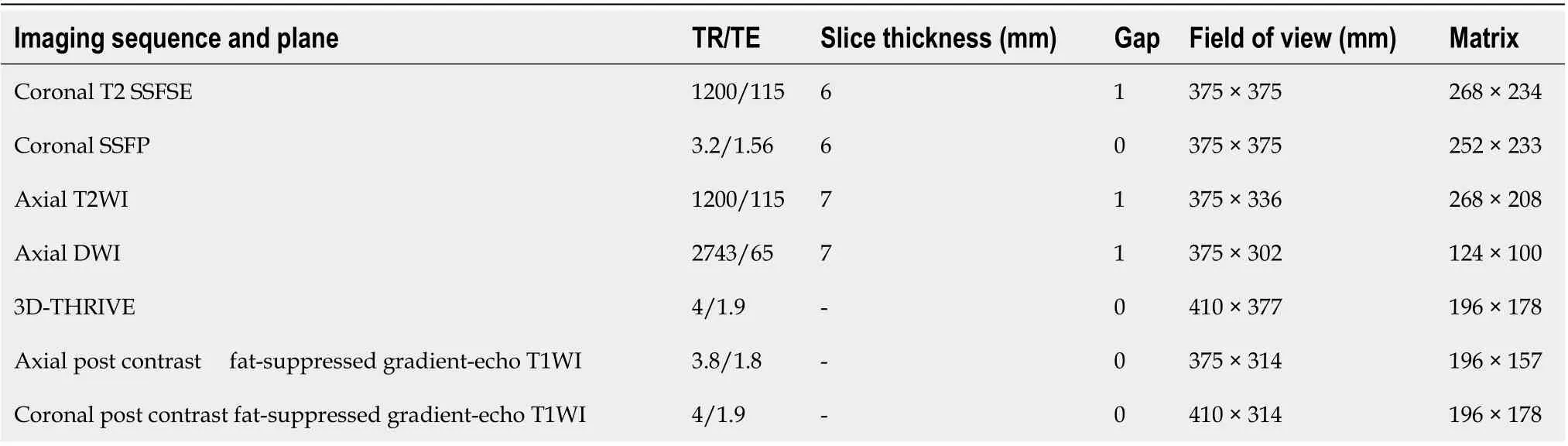

The patient was instructed to have a low residue diet the day before the examination and was asked to fast at least 6 to 8 h before the onset of the procedure. Ingestion of 1 to 2 L of hyperosmolar oral contrast was performed for about 45 min before the magnetic resonance (MR) exam started. After full distension of the bowel, a spasmolytic medication was given to decrease bowel peristalsis to provide better bowel visualization. The examination was performed on 1.5-T MR machine, Achieva, Philips Medical System, Best, Netherlands in MRI Unit, Ain Shams University Hospital. The patient was laid in supine position using a multi-element phased array Torso coil (16 channels). A dedicated MR study was then performed as described in Table 1. Pixel-based apparent diffusion coefficient maps were generated on the off-line workstation (extended workspace ‘‘EWS’’), Pride software (Philips Medical Systems). Intravenous gadolinium contrast was given (0.2 mmol/kg body weight) in dynamic fashion obtaining three-dimensional enhanced T1 isotropic volume excitation (3DeTHRIVE) coronal scans at 10 s, 20 s, 60 s, 70 s, and 90 s. The total MRE procedure took about 30 to 45 min.

The images were interpreted by a radiologist with 12 years of experience in abdominal imaging and who was also blinded to the clinical and colonoscopy examination results.

The MRE evaluated bowel wall thickening, mural edema, enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, restricted diffusion, peri-enteric vascularization (comb sign), peri-enteric fluid, and presence of complications, such as abscesses or fistulas.

Table 1 Magnetic resonance enterography imaging protocol

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software (22.0 version: SSPS Inc., Chicago, IL. United States). Description of quantitative variables was expressed in the form of mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) or median and inter-quartile range. A description of qualitative variables was expressed by frequency and percentage. Comparison of qualitative variables was carried out using the chi-square test.P< 0.05 was taken as significant. The sensitivity, specificity, overall correctness of prediction, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated. Correlations were calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and areas under the ROC (AUROC) curves were applied to evaluate the prognostic values (specificity and sensitivity).

RESULTS

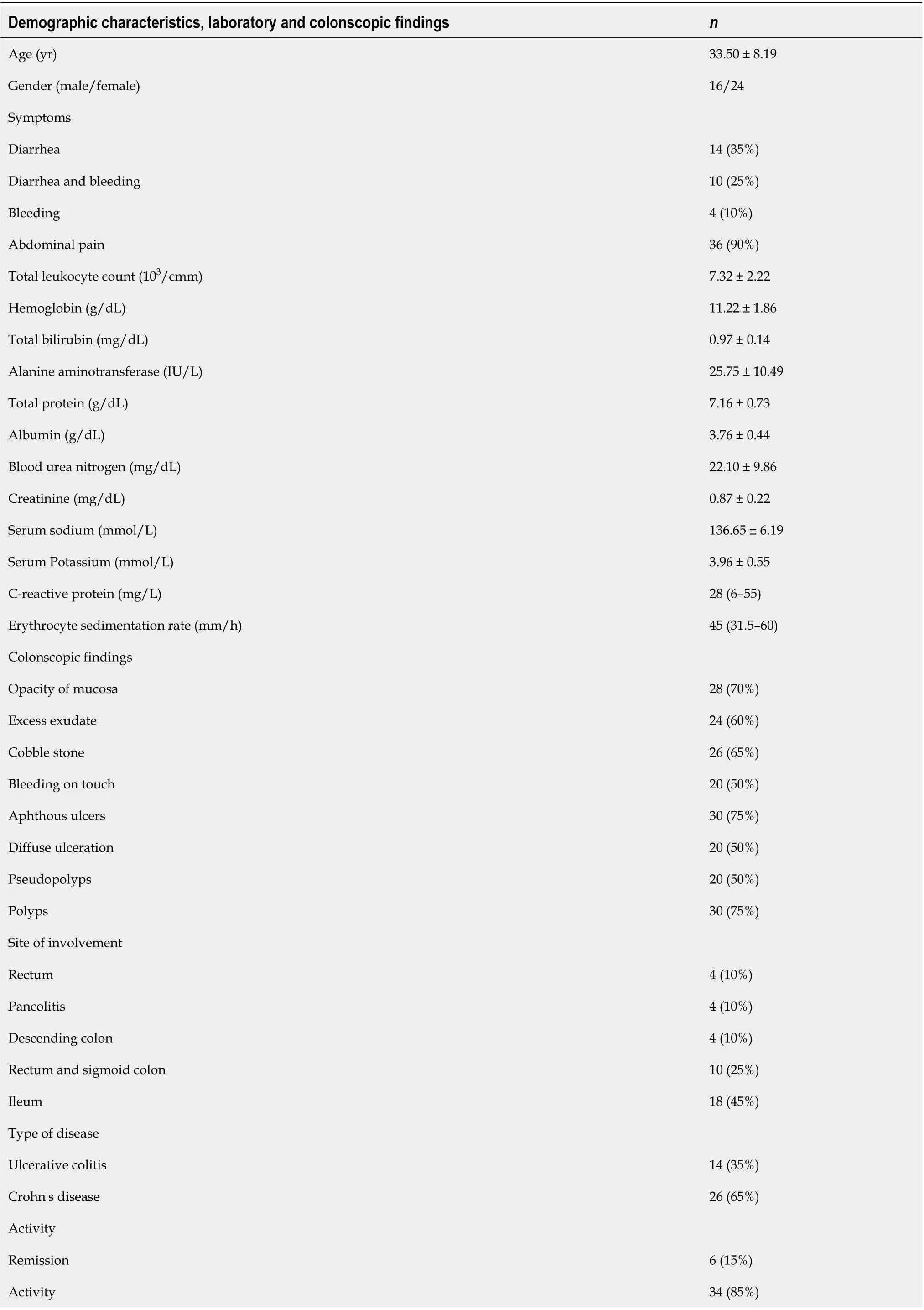

The demographic profile, clinical and laboratory parameters are shown in Table 2. Most of the patients were middle-age females who usually presented with abdominal pain and diarrhea. The result indicated that 14 (35%) of our patients had ulcerative colitis, and 26 (65%) had Crohn's disease while 34 (85%) of them were inactive. Four (4%) of studied patients had pancolitis, and 18 (45%) of the studied cases had ileal lesions.

Table 3 indicates that the bowel ultrasound appeared to be a good predictor for detection of ileal affection with sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of 93.8%, 50%, and 85%, respectively. With respect to the large bowel, bowel ultrasound detected large bowel affection with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 37.5%, 91.7%, and 70%, respectively. Also, bowel ultrasound was a good predictor for detection of thickness of affected segment with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 83.3%, 50%, and 60% respectively. Also, bowel ultrasound was a good predictor for detection of fistulous track with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 85.7%, 100%, and 95%, respectively, while sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 100%, 94.4%, and 95%, respectively, for detection of stricture and proximal dilatation were found. Abscess was detected by bowel ultrasound in six patients with high specificity, sensitivity, and accuracy (100%). Also, bowel ultrasound showed that no statistically significant differences between bowel ultrasound and disease activity index, which indicates that bowel ultrasound can differentiate between remission and active disease (Figure 1).

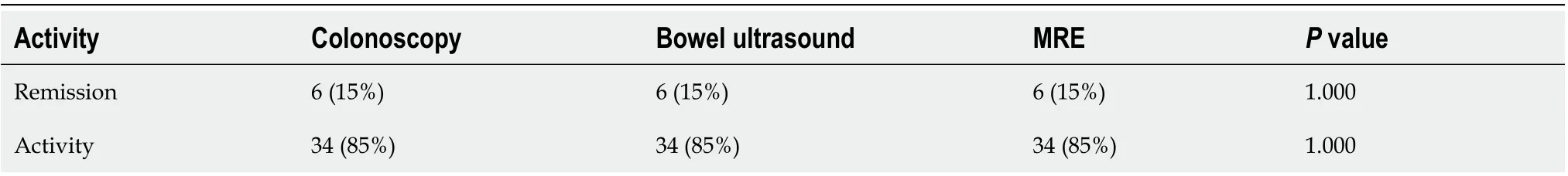

Table 4 indicates that no statistically significant difference among bowel ultrasound, MRE, and colonoscopy for detection of activity of the disease was noted, indicating that bowel ultrasound and MRE can differentiate between remission and active IBD (Figure 2).

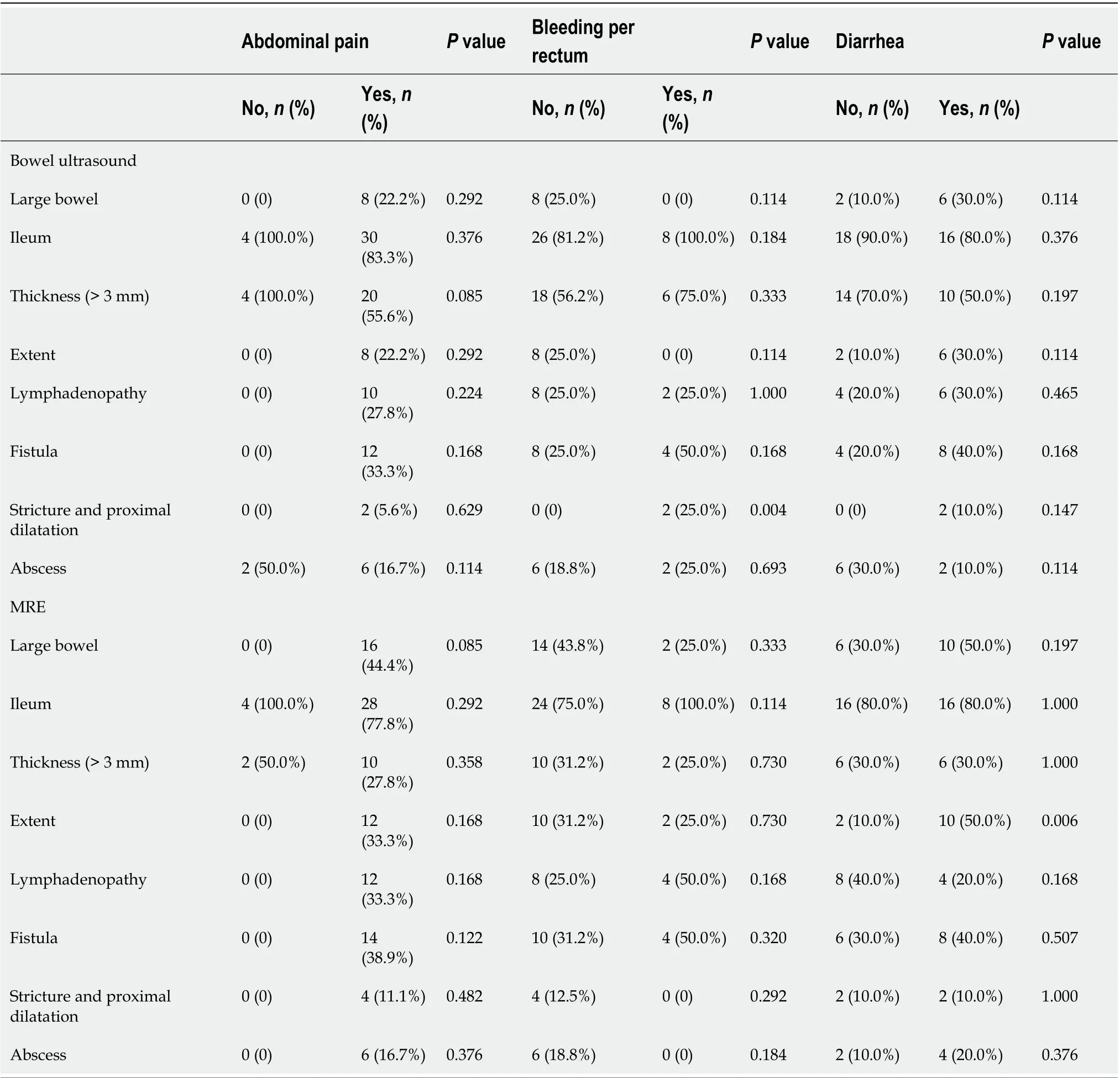

Table 5 compares between clinical symptoms and imaging modalities bowel ultrasound and MRE. It indicates that bleeding per rectum is statistically significant in patients with strictures and proximal dilatation during assessment by bowel ultrasound, while diarrhea is statistically significant to the extent of the lesions when assessed by MRE.

Table 2 Demographic characteristics, laboratory and colonscopic findings of the total 40 studied cases

Table 3 The diagnostic characteristics of the bowel ultrasound in the detection of small intestinal and large bowel disease and its correlation to disease activity index

Table 4 Comparison between bowel ultrasound, magnetic resonance enterography and colonoscopy as regards the detection of disease activity and remission

DISCUSSION

Endoscopy is still the most important diagnostic procedure as it permits taking biopsy for histological examination[11]. European guidelines have recommended imaging techniques, such as bowel ultrasound, computed tomography enterography, and MRE as complementary tools for IBD diagnosis that can help define its location, extension, and complications[12].

MRE is a cross-sectional non-ionizing imaging technique that can be used for IBD diagnosis and extrainstestinal assessment of disease activity and followup of patients. But MRE is available at certain centers only and it takes long time during scanning with sedation in some cases such as children to avoid motion artefacts besides noncompliance to contrast intake and breath-hold technique[13].

Assessment of gastrointestinal tract in IBD patients by intestinal ultrasound was evolved nowadays due to development of ultrasound devices and rising skillfullness of their examiners as radiologists and gastroenterologists. Major parts of the small and large intestine can be easily examined by bowel ultrasound while proximal part of jejunum and the rectum may be difficult in their assessment due to overlying structures. Inspite of different advantages of bowel ultrasound as a rapid bedside,inexpensive and non-radiating tolerable test but its results are subjective to the examiner's expertise[14].

Our results showed similar sensitivity for detection of ileal IBD in comparison to one previous study (92.7%) but with lower specificity than this study (88.2%). Regarding colonic IBD, our results showed lower sensitivity than observed in this previous study (81.8%) but with similar specificity (95.3%), a finding which may be explained by interobserver variability between examiners[13]. This variability can explain why one study concluded that bowel ultrasound is more accurate for assessment of IBD patients if combined with colonoscopy[16].

Table 5 Comparison between clinical symptoms and imaging techniques; bowel ultrasound and magnetic resonance enterography

A bowel wall thickness cutoff value of 3 mm in our study showed sensitivity (83.3%), specificity (50%), and accuracy (60%) in comparison to other studies, which showed sensitivities of 88% to 94%; however, specificity (93%-97%,) and diagnostic accuracy (94%) were higher in previous studies than in our study[9,15]. This finding can be explained by the lack of international agreement about standardized measurement parameters, which leads to interobserver variability between examiners[18].

Mesenteric lymph nodes detected by bowel ultrasound in our study were nonsensitive and non-specific (16.7% and 71.4%, respectively) and insignificantly subsided during remission; therefore, lymph nodes detection was not a good parameter of activity in agreement with some previous studies[19,20].

Our study agreed with different trials in which it was shown that detection rate of fistulas, depending on their localization, had sensitivity between 67% and 82% and specificity between 90% and 100%[8,9,21-23].

Stricture in our study as detected by bowel ultrasound showed sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy (100%, 94.4%, and 95%, respectively) were similar to other studies[15,24-26].

The sensitivity for detecting abscesses in different studies varied between 80% and 100%, and specificity varied between 92% and 94%, which were similar results to ours[27-29].

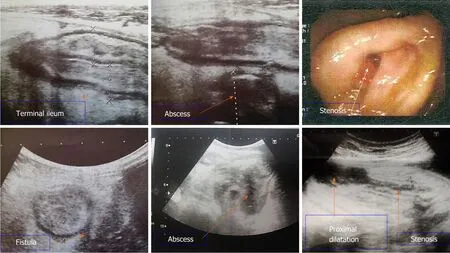

Figure 1 Bowel ultrasound and colonoscopy images. Bowel ultrasound demonstrates diffuse terminal ileal wall thickening likely of inflammatory nature with sonographic evidence of fistulization with mesenteric abscess formation. Stenosis which was detected during colonoscopy was seen by bowel ultrasound with proximal dilatation.

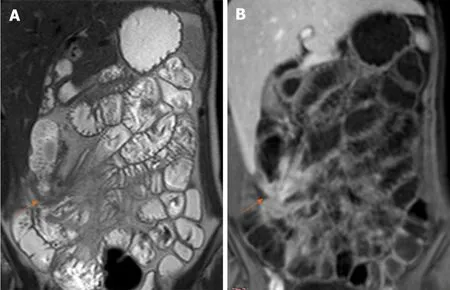

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance enterography. A: Coronal T2WI shows enteroenteric fistula at the right iliac fossa with stellate appearance of the thickened ileal loops (white arrow); B: Coronal fat-suppressed three-dimensional gradient echo postcontrast T1WI shows accentuated star-like enhancement at the right iliac fossa denoting fistulizing crohn’s disease.

Our study agreed with different trials in which it was shown that diagnosis of IBD and assessment of its activity cannot be dependent on clinical evaluation alone but should by combined with other investigations such as biomarkers, endoscopy, and imaging techniques such as bowel ultrasound and MRE[25,30].

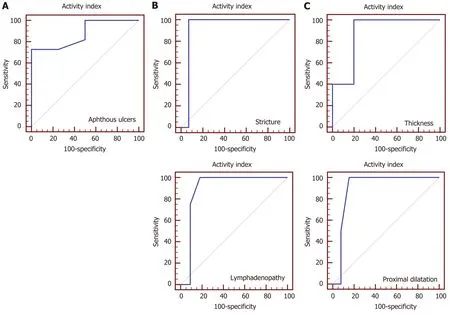

Our results showed that aphthous ulcers at endoscopy, stricture and mesenteric lymphadenopathy at bowel ultrasound, thickness of bowel wall and proximal dilatation at MRE were significantly correlated to disease activity (Figure 3). Other studies showed that other different bowel ultrasound parameters such as bowel wall thickening and its extent showed a significant correlation with disease activity[26,31,32]. Regarding MRE results in our study agreed with some studies[33,34]and disagree with another[35].

This indicates that there is no clear gold standard imaging technique for IBD diagnosis including MRE or bowel ultrasound which could be used besides clinical history, biomarkers, endoscopy for diagnosis of IBD as agreed with previous studies[25,30,36].

Figure 3 Receiver operating characteristic curve for prediction of active disease. A: At endoscopy, aphthous ulcers mean area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was 0.875 (P < 0.001), positive likelihood ratio infinity, and negative likelihood ratio 0.28; B: Bowel ultrasound showed stricture and lymphadenopathy mean area under the ROC curve were 0.929 (P = 0.036) and 0.898 (P = 0.01) respectively, positive likelihood ratio infinity for both, and negative likelihood ratio 0.94 and 0.71 respectively; C: Magnetic resonance enterography showed thickness and proximal dilatation mean area under the ROC curve were 0.880 (P < 0.001) and 0.904 (P = 0.033) respectively, positive likelihood ratio 1.06 and infinity respectively, and negative likelihood ratio 0.88 for both.

Bowel ultrasound can be more helpful in follow-up of IBD patients and monitoring of their response to treatment away from its role of diagnosis by ultrasound guided biopsy.

In Egypt, both MRE and colonoscopy are available tools with estimated total cost of $93 dollars and $125 dollars respectively. Bowel ultrasound costs only 18$ dollars which is considered as a low cost alternative and has prospects for widespread clinical use.

Limitations of our study were the relatively small number of included patients, and comparative assessments of clinical decisions with and without bowel ultrasound were not available.

CONCLUSION

In comparison to MRE and colonoscopy, bowel ultrasound is a useful non-invasive and feasible bedside imaging tool for the detection of inflammation, complications, as screening tool and follow-up of IBD patients when performed by the attending physician.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research motivation

Up until now, no previous published comparative studies between bowel ultrasound and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) for Egyptian inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients.

Research objectives

Compare between the role of bowel ultrasound and MRE in Egyptian IBD patients.

Research methods

The study was conducted on 40 patients presented to IBD center of Ainshams University Hospitals. The patients were subjected to clinical, laboratory, colonoscopic and radiological assessments including bowel ultrasound and MRE.

Research results

Bowel ultrasound was a good predictor of disease activity, fistula, stricture, and abscess formation with high sensitivity in ileum and more specificity in large bowel.

Research conclusions

Bowel ultrasound is a useful bedside cheap imaging tool that can be used for diagnosis and follow-up of IBD patients.

Research perspectives

Further studies to compare clinical decisions with and without bowel ultrasound.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年38期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年38期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Role of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of oesophageal neoplasia: 2020 an endoscopic odyssey

- Molecular mechanisms of viral hepatitis induced hepatocellular carcinoma

- Tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil as second-line treatment in autoimmune hepatitis: Is the evidence of sufficient quality to develop recommendations?

- Monitoring hepatitis C virus treatment rates in an Opioid Treatment Program: A longitudinal study

- Endoscopic ultrasound-measured muscular thickness of the lower esophageal sphincter and long-term prognosis after peroral endoscopic myotomy for achalasia

- Longitudinal decrease in platelet counts as a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis