Monitoring hepatitis C virus treatment rates in an Opioid Treatment Program: A longitudinal study

Arantza Sanvisens, Inmaculada Rivas, Eva Faure, Nestor Espinach, Anna Hernandez-Rubio, Xavier Majo,Joan Colom, Robert Muga

Abstract

Key Words: Direct-acting antiviral agents; Opioid Treatment Program; Opioid agonist therapy; Hepatitis C virus infection; Human immunodeficiency virus infection; Drug use

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that 10 million people with substance use disorder (SUD) have hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection[1]. In addition, it is believed that a proportion of HCV infections remain undiagnosed in individuals with SUD. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 23% of new HCV infections occur in patients with SUD[2]. In the United States and western Europe, two out of every three new HCV infections are believed to be associated with substance use[2].

The introduction of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) in 2013 caused substantial changes in the clinical outcomes of HCV infection. Pharmacotherapy for HCV infection is administered for shorter periods of time (i.e., 8-12 wk) and sustained virological responses (SVR) are achieved in over 90% of patients, irrespective of the HCV genotype. Several studies have revealed that DAAs showed efficacy in difficultto-treat populations, including individuals with SUD[3-8].

The WHO aims to eliminate HCV infection by 2030. The defining features of that goal are to achieve a 90% reduction in new cases, diagnose 90% of all individuals infected with HCV, treat 80% of those eligible, and reduce death by 65%. In this context, individuals with SUD have been recognized as a target population for improving the identification of HCV-related disease and for implementing HCV micro-elimination strategies[9-11]. The strategy is to promote a cascade of care, or a continuum of services that should be provided to cure HCV in persons living with hepatitis[2].

Current guidelines for HCV care and treatment are provided, among others, by the American Association for the Study of the Liver (AASLD), the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), and the WHO[12-14]. All of these organizations recommend DAAs for treating HCV infection, including in individuals with SUD. Indeed, several studies have indicated that SUDs did not affect adherence to treatment or imply worse response rates[15-17].

More than 120000 people have been treated with DAAs since the Strategic Plan for Tackling Hepatitis C was implemented by the Spanish National Health System in 2015[18]. At the same time, up to 60000 patients are regularly treated with opioid agonist therapy (i.e., methadone) in Spain. Individuals treated with methadone might have a history of injected drug use, and consequently, they might have acquired blood-borne infections, like HCV, after they began injecting drugs[19]. A previous study on individuals that participated in Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) in Catalonia, Spain, showed that the prevalences of HCV and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections were 74% and 54%, respectively[20].

We hypothesized that in the context of the changes made in the provision of HCV care, OTP sites might be experiencing increasing proportions of patients that are eligible for HCV treatment. Therefore, we studied OTP participants to analyze assessment of infection, treatment rates, and predictors of treatment with DAAs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This longitudinal study included ex-heroin users enrolled in an OTP between October 2015 and September 2017. The OTP operates in a municipal outpatient clinic specialized in the treatment of SUDs in Badalona (240000 inhabitants) and Santa Coloma de Gramenet (120000 inhabitants), Spain. The selection process of the study population was conducted in the only addiction clinic for the provision of methadone in both cities during the study period.

In the OTP, methadone is dispensed on site,viaa mobile unit (Intercity Methadone Bus), and in five community pharmacies. In addition, the outpatient clinic conduct harm reduction programs, which include needle exchanges, condom distribution, and psychosocial interventions[21].

For OTP inclusion, patients had to be over age 18 years and they had to have an opioid dependence diagnosis, based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4thedition criteria[22]. Additional details have been described previously[20,21]. The municipal clinic was affiliated with primary care centers and nearby hospitals, where patients were referred for confirmatory tests (e.g., HCV-RNA), radiology (e.g., ultrasound), and consultations with specialists (e.g., hepatologists). Physicians at the OTP clinic did not evaluate liver disease or treat HCV infection; those patients were referred to the hospital, where hepatologists and/or internist treated HCV infection. The Spanish health system provided universal access to DAAs, but these drugs were only dispensed in hospital pharmacies.

Ethics

Patients were informed of the objective of the study, and all patients provided written consent. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol (PI-15-100). This study was compliant with ethical standards for medical research and good clinical practice principles, and it was performed in accordance with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki.

Variables

We collected data on socio-demographic variables (education level, employment, and prior imprisonment), opioid use (age at first drug use, main route of administration), biochemistry and hematological parameters, including liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, gamma glutamyl transferase, and total bilirubin). We also ascertained the presence of HIV and HCV infections and HCVRNA, the genotype, and any antecedent of HCV treatment with interferon-based regimens.

Follow-up

Patients that tested anti-HCV positive and had not previously received IFN/RBV treatment regimens were followed-up until September 30, 2019. Specifically, we reviewed clinical charts to ascertain data on HCV-RNA, the genotype, and DAA treatments, including the date of initiation, type, duration, and clinical outcome (i.e., SVR). In addition, we checked the national death registry for all patients.

Statistical analysis

We performed a descriptive analysis of the data. Continuous variables are presented as the median and interquartile range (IQR); categorical variables are presented as the relative frequency. We performed Chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact tests, Student’sttests, and Mann WhitneyUtests, when appropriate, to detect statistically significant differences between groups. To analyze treatment rates and predictors of treatment with DAAs, we excluded patients treated with IFN/RBV from the analysis. Patient follow-up was evaluated from January 2015 (when DAAs were introduced in Spain) until death or the end of the study, on September 30, 2019. Patient follow-up data were calculated in terms of person-years (p-y). Rates in p-y were defined as the quotient of the number of events observed during the study period (in the numerator) and the sum of all the individual follow-up times (in the denominator). We used Kaplan-Meier methods to estimate the cumulative incidence of treatment with DAAs. Cox regression models were used to analyze predictors of DAA treatment administration. All covariates that were significant in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate analysis.Pvalues < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata software (version 11.0; College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

Between October 2015 and September 2017, 501 patients (81.4% men) were enrolled in the OTP. The median age at study entry was 45 years (IQR: 39-50 years), 88% were Spanish-born and 96% of patients had been on opioid agonist therapy for more than 10 years (on average, since 2006; IQR: 2000-2014). The majority of patients (98.5%) was treated with methadone, 70% were unemployed, 49.5% had a history of incarceration and 65% had used injected drugs.

A total of 336 (67%) patients tested positive for anti-HCV antibodies (83% men; median age 46 years, IQR: 41-51 years); these patients had been taking opioid agonist therapy for a median of 15.3 years (IQR: 5.6-19.2 years). The prevalence of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine use at study entry was 47.2%, 41.3%, and 31.9%, respectively. The prevalence of HIV co-infection was 47.6% (160/336). The characteristics of anti-HCV positive patients are shown in Table 1.

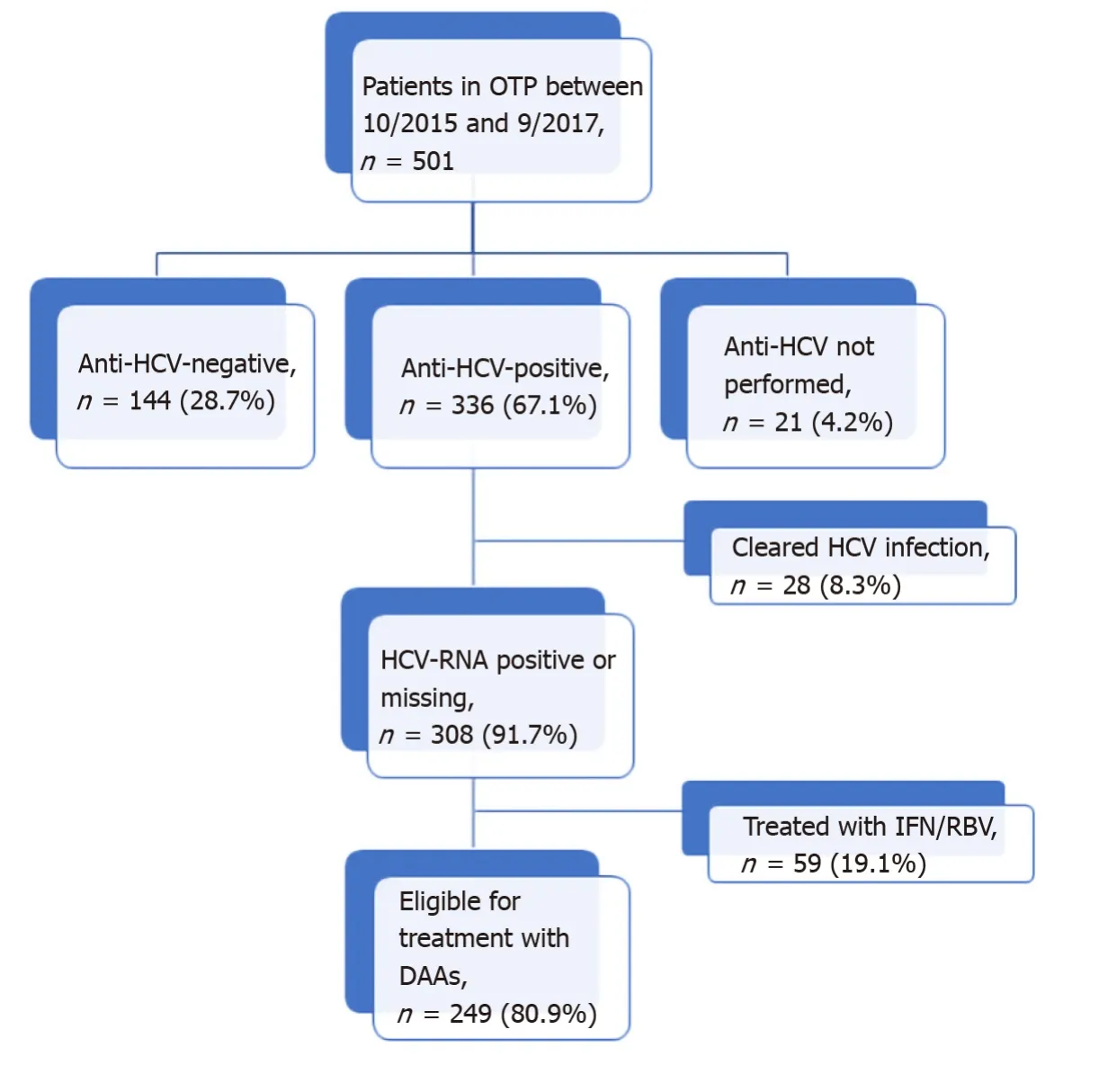

Of the 336 anti-HCV positive patients, 233 (69.3%) had positive results on an HCVRNA test. The median of HCV-RNA was 11.4 (IQR: 1.5-44.8) × 105IU/mL and the majority (59.2%) of cases were genotype1a/1b. Only 28 (8.3%) patients had cleared the infection, and 59/308 (19.1%) had been previously treated with IFN/RBV. HCV-RNA was not determined in 75 patients that were anti-HCV positive (22.3%). The distribution of patients according to HCV infection status is shown in Figure 1.

Rates and predictors of HCV treatment with DAAs

As of September 2019, among the 249 patients eligible (Figure 1) for DAA treatment, 111 (44.6%) were treated. Of those, 90% achieved SVR. The most frequent DAA combinations were sofosbuvir/ledipasvir, sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, and glecaprevir /pibrentasvir.

Rates and predictors of whether patients received DAA treatment

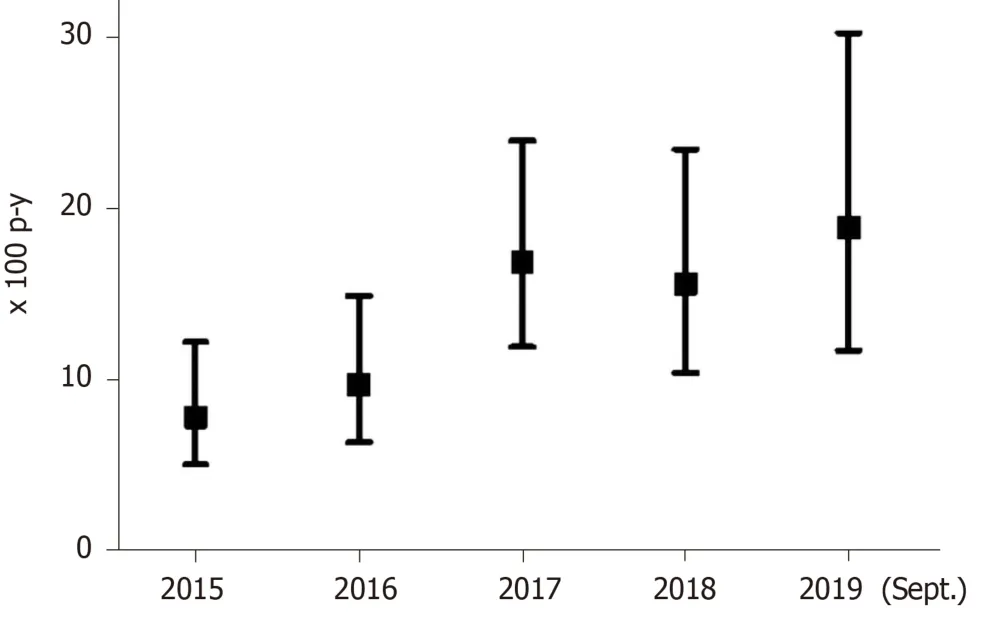

The 249 patients eligible for DAA treatment were followed-up for a median of 4.3 years (IQR: 2.4-4.7 years; total follow-up 879.3 p-y). The overall DAA treatment rate was 12.6/100 p-y (95%CI: 10.5-15.2) and treatment rates increased from 7.8/100 p-y (95%CI: 5.0-12.3), in 2015, to 18.9/100 p-y (95%CI: 11.7-30.3), in 2019.

Figure 2 shows treatment rates with DAAs since 2015. Patients with HCV-HIV coinfection had a treatment rate of 18.0/100 p-y (95%CI: 14.2-22.8); in contrast, patients with HCV mono-infection had a treatment rate of 8.6/100 p-y (95%CI: 6.4-11.7), (P< 0.001). Thus, the incidence rate ratio was 2.09 (95%CI: 1.4-3.1).

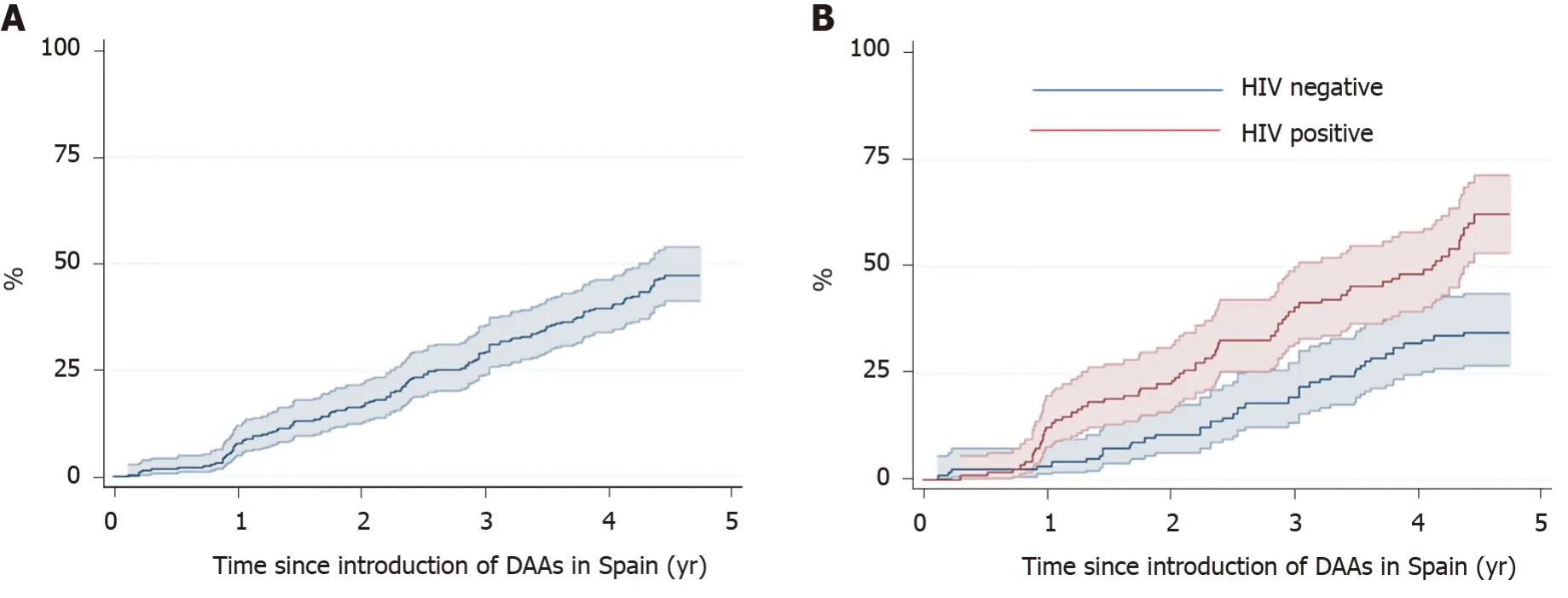

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier estimates of receiving treatment with DAAs. After four years, the probability of receiving DAA treatment was 39.5% (95CI%: 33.6-46.0) overall, 32% (95CI%: 24.4-41.0) in the HCV mono-infected patients, and 48.1% (95%CI: 39.3-57.8) in the HIV co-infected patients (P< 0.001).

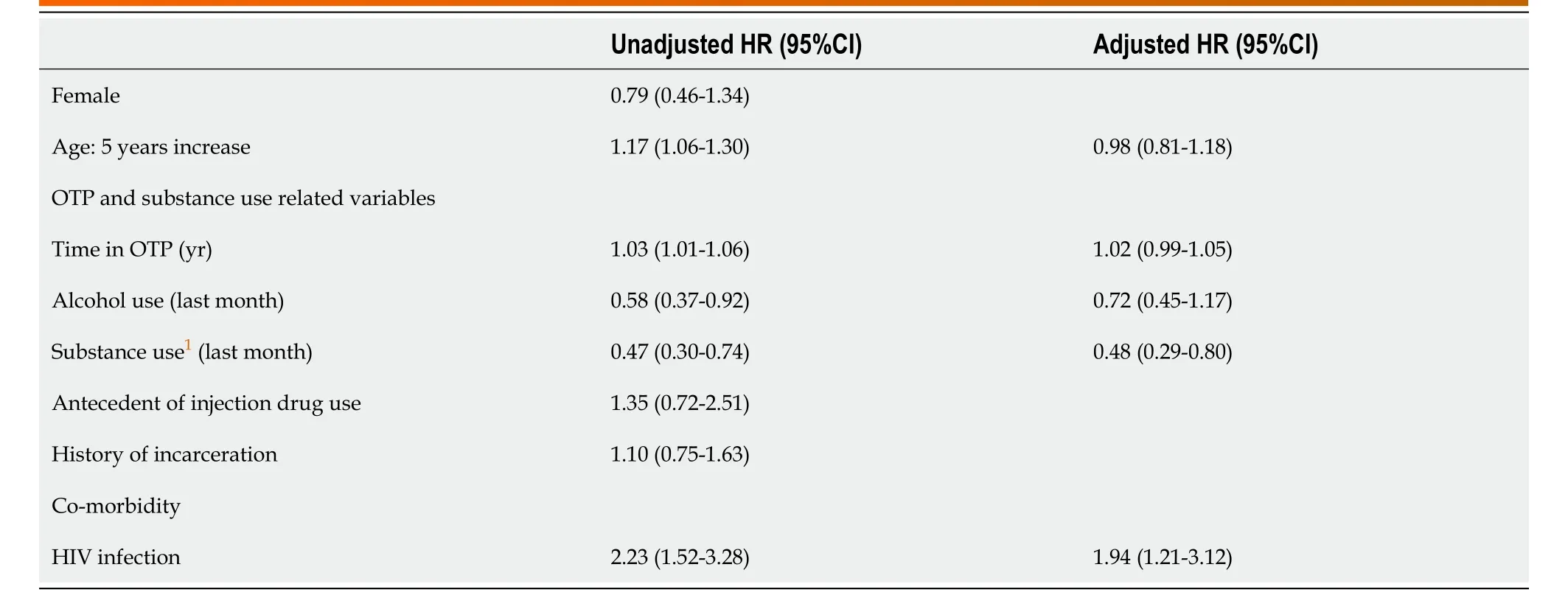

The Cox regression models showed that HIV co-infected patients were twice as likely to receive HCV treatment, compared to those with HCV mono-infection (HR = 1.94, 95%CI: 1.21-3.12,P= 0.006). In addition, patients with ongoing drug use while in the OTP were 2.1-fold less likely to receive DAAs (HR = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.29-0.80) compared to those who do not used drugs (P= 0.004). The Cox regression models on predictors of treatment are shown in Table 2.

Table 1 Sociodemographics, substance use characteristics and blood parameters of anti-hepatitis C virus positive patients in an Opioid Treatment Program

DISCUSSION

This study provides a snapshot of the access to curative HCV treatment in patients treated with methadone. Furthermore, it shows that after the introduction of DAAs in Spain, nearly 50% of patients with an anti-HCV positive test were treatment naive. Moreover, we observed significantly lower rates of treatment among patients with HCV mono-infection than among patients with HCV-HIV co-infection.

Few studies in Spain have analyzed DAA treatment rates among patients enrolled in an OTP. In contrast, a European study showed that, after the introduction of DAAs, HCV treatment rates were 23/100 p-y among individuals that injected drugs and had HCV-HIV co-infection[23], which was twice the rate observed in our study. However, it is interesting to note that, since 2015, the proportion of patients that received treatments against HCV infection has increased and that DAA treatment showed efficacy in this difficult to treat population. In fact, the HCV treatment guidelines provided by the AASLD, EASL, and WHO have recommended individualized treatments for patients in the OTP[12-14].

In this study, HIV co-infection and ongoing drug use while in OTP were two independent predictors of whether a person received HCV treatment. The probability of being treated against infection was significantly higher in the co-infected group compared to the HCV mono-infection group. This finding might be related todifferences in the continuum of care in the HCV mono-infected and the HIV coinfected. In Spain, HCV mono-infected patients receive regular care and treatment in hospital-based Hepatology units while HCV-HIV co-infected patients are managed in HIV/Aids units having integrated services, psychosocial support and flexible timeslots for visits.

Table 2 Cox regression models for predictors of hepatitis C virus-treatment with direct antiviral agents

Figure 1 Flowchart of patients visited in the Opioid Treatment Program and hepatitis C virus infection status. OTP: Opioid Treatment Program; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; DAAs: Direct antiviral agents.

In this cohort, current drug use was associated with a lower probability of receiving HCV treatment. In this sense, health care professionals may perceive current drug use as a barrier to prescribe HCV treatment, despite international guidelines that recommend treatment of infection[12-14]. In patients with SUD, treating HCV infection has been considered a preventive intervention aimed to halt the transmission[24,25]. A recent clinical trial used electronic blisters to monitor adherence to DAA treatment among patients that used drugs and were in an OTP; they showed that 97% of participants completed the treatment, and 94% achieved SVR[5].

Figure 2 Annual rates of hepatitis C virus treatment with direct antiviral agents in an Opioid Treatment Program. p-y: Person-years.

Figure 3 Kaplan Meier estimates (95%CI) of direct antiviral agent treatment for hepatitis C virus. Plots included (A) all patients and (B) patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) mono-infection and HCV-human immunodeficiency virus co-infection. HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; DAAs: Direct antiviral agents.

This study had some limitations. First, the external validity of the results might have been limited due to the single-center study design. However, the OTP studied was the largest operating in metropolitan Barcelona, Spain, and only authorized to provide methadone or buprenorphine in a large urban area. Second, data related to the dose of methadone were not available and we also lacked data on treatment adherence and potential pharmacological interactions that might have led to DAA discontinuation. However, few studies have reported significant pharmacological interactions between DAAs and methadone[26,27]. Although some DAAs can increase the methadone or buprenorphine concentrations in blood, dose adjustments are not required, and monitoring withdrawal symptoms is merely recommended[27,28]. Third, we could have underestimated the HCV treatment rate with DAAs because some anti HCV-positive patients were considered treatment eligible without having a confirmatory RNA-HCV test.

In contrast, our study population is anchored in an OTP with a large number of patients and real-world conditions which is relevant to generate evidence in a population difficult to treat and retain.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study highlights the challenges of measuring the continuum of HCV care while in an OTP. The goal of HCV elimination requires more targeted interventions to rapidly identifying those out of care.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年38期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年38期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Role of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of oesophageal neoplasia: 2020 an endoscopic odyssey

- Molecular mechanisms of viral hepatitis induced hepatocellular carcinoma

- Tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil as second-line treatment in autoimmune hepatitis: Is the evidence of sufficient quality to develop recommendations?

- Comparative study between bowel ultrasound and magnetic resonance enterography among Egyptian inflammatory bowel disease patients

- Endoscopic ultrasound-measured muscular thickness of the lower esophageal sphincter and long-term prognosis after peroral endoscopic myotomy for achalasia

- Longitudinal decrease in platelet counts as a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis