Tale of fat and fib — cardiac lipoma managed with radiofrequency ablation: A case report

Swarna Sri Nalluru, Srinivas Nadadur, Nitin Trivedi, Sunita Trivedi, Sanjeev Goyal

Abstract

Key words: Cardiac lipoma; Lipomatous hypertrophy of interatrial septum; Atrial fibrillation; Radiofrequency ablation; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac lipomas constitute approximately 10% of benign cardiac tumors. They are most commonly noted in interatrial septum (IAS) followed by the right atrium and left ventricle[1]. Lipomas involving the IAS should be differentiated from lipomatous hypertrophy of interatrial septum (LHIS) as they both have similar features on imaging except for the characteristic sparing of fossa ovalis in LHIS. In addition, the interatrial septal thickness of > 2 cm is considered diagnostic for LHIS. Cardiac lipoma and LHIS typically have a benign course with asymptomatic subjects[2]. In symptomatic patients, the clinical symptoms and outcome vary depending on the tumor size and location[3]. Differentiating cardiac tumors is essential for symptomatic patients as treatment and prognosis vary[2]. Although biopsy provides a definitive diagnosis, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was found superior to computerized tomography (CT) and aids in differentiating several lesions[4]. Surgical excision remains the main modality of treatment in cardiac lipoma and LHIS cases.Complete removal of the lipoma with capsule and pedicle ensures prevention of recurrence[5]. Here, we report a woman presenting with intractable arrhythmias resulting from unresectable cardiac lipoma and LHIS, who was successfully managed with cardiac radiofrequency ablation.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 63-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the outpatient cardiology office with dyspnea on exertion and weakness.

History of present illness

Patient presented with recent onset dyspnea on exertion and weakness for 1-2 wk.Review of systems was positive for palpitations, fatigue and weight gain, but negative for chest pain, syncope, fever and cough.

History of past illness

Past medical history included hypertension, hypothyroidism, right breast ductal cell carcinoma treated with mastectomy and breast implant, platelet granule disorder,asthma requiring chronic intermittent prednisone use.

Physical examination

Physical examination revealed a regular pulse of 72/min, blood pressure 138/95 mmHg and body mass index 26.7 kg/m2. Cardiac examination revealed normal heart sounds without murmur or gallop. Her lungs were clear to auscultation. Bilateral trace pitting edema was noted at her ankles.

Laboratory examinations

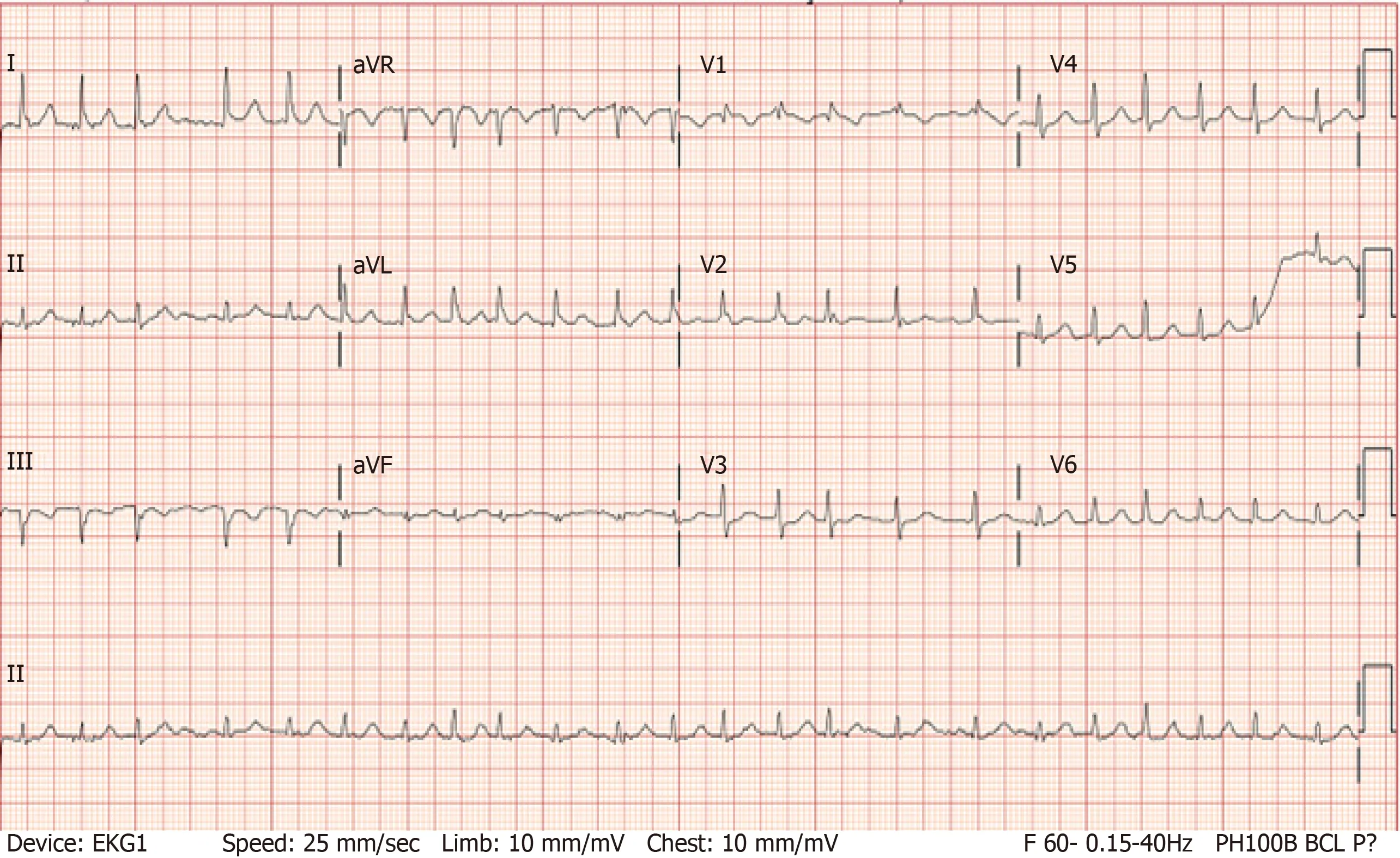

Electrocardiogram (EKG) showed normal sinus rhythm with right bundle branch block (RBBB), unchanged from prior EKG. Thirty-day event monitoring showed 3 episodes of isolated supraventricular ectopics which represented < 0.1% of the total beat count. During hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia, the patient developed symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) (Figure 1).

Imaging examinations

Transthoracic echocardiogram showed a right ventricular (RV) mass, preserved RV function and a preserved ejection fraction of 60%-65%. A biopsy was not pursued given the high risk of bleeding due to platelet granule disorder. Cardiac MRI showed LHIS as well as well-defined capsular mass along the epicardial surface of RV free wall diffusely infiltrating the myocardium and mediastinal lipomatosis (Figure 2). No early or late enhancement of mass with gadolinium contrast was seen, suggesting a benign cardiac lesion. The characteristic features of the lesions in RV and IAS on fat suppression of the imaging provided a diagnosis of cardiac lipoma and LHIS respectively.

Further diagnostic work-up

Genetic testing for arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD) and 24-h urine cortisol test was negative.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY EXPERT CONSULTATION

Sanjeev Goyal, MD, Assistant Professor, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Cardiology, Saint Vincent Hospital

For diagnosis of the lesion identified on transthoracic echocardiogram, Biopsy is more definitive but given the history of severe bleeding due to underlying platelet granule disorder and the patient's reluctance to undergo surgical procedures, Patient needs to undergo cardiac MRI for diagnosis of the lesion.

Brian B Ghoshhajra, MD, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital

Cardiac MRI showed well-defined capsular mass along the epicardial surface of RV free wall diffusely infiltrating the myocardium and mediastinal lipomatosis. There is diffuse infiltration of the mass into the right ventricular myocardium without frank invasion of extracardiac structures. The mass is homogeneously hyperintense on T1 and demonstrates signal drop on fat-saturated sequences. No early or late enhancement of mass with gadolinium contrast was seen suggesting a benign cardiac lesion. There is also lipomatous hypertrophy of the interatrial septum. The characteristic features of the lesions in right ventricle and interatrial septum on fat suppression of the imaging provided a diagnosis of cardiac lipoma and LHIS respectively.

Sanjeev Goyal, MD, Assistant Professor, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Department of Cardiology, Saint Vincent Hospital

Patient was provided referral to cardiothoracic surgery for surgical resection of the cardiac lipoma. She failed to follow-up, refused any surgical interventions and opted for medical management.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the presented case is atrial fibrillation in the setting of cardiac lipoma and LHIS.

Figure 1 Electrocardiogram showing atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response.

TREATMENT

Prednisone was discontinued. Multiple attempts at rhythm control of her symptomatic paroxysmal AF failed with sotalol and flecainide. As the mass could not be resected, pulmonary vein isolation and right atrial isthmus radiofrequency ablation were done.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Post-procedure, EKG showed normal sinus rhythm with RBBB. She is in follow-up with no recurrence of AF for 10 mo along with no symptoms. Recent thirty-day event monitoring also showed no significant record of AF.

DISCUSSION

We describe an interesting case of a 63-year-old non-obese woman presenting with intractable AF most likely due to cardiac lipoma and LHIS. These clinical entities are very rare and a simultaneous presentation in a single patient, to the best of our knowledge, was never reported. Lamet al[6]reviewed 12485 autopsies performed over a 20-year period and reported a 0.056% prevalence of primary cardiac tumors and cardiac lipoma represented an even smaller fraction[6]. Most patients with cardiac lipoma are asymptomatic; however, the clinical features of cardiac lipoma vary from dyspnea to palpitations, dizziness, decreased exercise tolerance, thromboembolism,and sudden death. An atypical presentation including fever of unknown origin,hypertension, and epistaxis have been noted[3]. A transthoracic echocardiogram performed in our patient for palpitation and decreased exercise tolerance showed the intracardiac masses. Although transvenous biopsy would be the next step in management, high risk of bleeding[7]given the presence of platelet granule release disorders warranted a different approach in our patient. Cardiac MRI is superior to CT and aids in differentiating cardiac masses including both benign and malignant[4].The characteristic fat saturation in MRI imaging suggested that the lesion mainly comprised of fat tissue with the differentials including lipoma, liposarcoma, ARVD,and LHIS. As malignant lesions have a more heterogeneous appearance with avid contrast enhancement, cardiac MRI findings of homogenous mass without contrast enhancement suggested a benign lesion in our patient. Given lack of liposarcoma features on MRI and a negative ARVD genetic test, the cardiac tumor in right ventricle was diagnosed as a lipoma. Interestingly, the fatty tissue in IAS was diagnosed as LHIS due to its characteristic dumb bell shape form and sparing of fossa ovalis[8].

Figure 2 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. A: Axial section T1 weighted imaging showing (a) well-defined capsular homogenous mass along the epicardial surface of right ventricular, diffusely infiltrating the myocardium without frank invasion of adjacent structures (b) lipomatous hypertrophy of interatrial septum; B: Axial section T1 weighted imaging showing signal drop on fat saturated sequence of cardiac lipoma in right ventricular. RV: Right ventricular; LHIS: Lipomatous hypertrophy of interatrial septum.

Lipomas are benign encapsulated fatty lesions with unclear etiologies[1]. A study done by Italianoet al[9]showed that solitary lipoma is associated with chromosome 12 gene rearrangements, where an abnormality in HMGA2-LPP fusion gene was noted.Multiple lipomas are associated with certain genetic disorders such as familial multiple lipomatosis, Gardner syndrome, adiposis dolorosa, and acquired conditions such as chronic corticosteroid use and chronic alcohol use (Madelung disease)[10].Deep-seated lipomas should be differentiated from liposarcoma, because lipomatous malignancy commonly occurs at sites deeper than the subcutaneous region. Our patient did not have any of the above-mentioned conditions except for chronic low dose corticosteroid use. Tailléet al[11]reported a case of corticosteroid-induced mediastinal lipomatosis and increased risk of mediastinal hemorrhage on anticoagulant therapy with steroids. Sorhageet al[12]described a case with regression of multiple symmetric mediastinal lipomatosis with discontinuation of corticosteroid.Prednisone was discontinued to prevent further progression and associated complications[13].

LHIS, although has fatty deposits, it is a separate entity from lipoma with variable pathology[1]. Heyeret al[14]showed an LHIS incidence of 2.2% by multi-slice CT.Higher prevalence of LHIS has been observed in patients with advanced age, atrial arrhythmias, obesity. It is unclear whether the presence of LHIS increased the risk of atrial arrhythmias. Nonetheless, postulated mechanisms for cardiac arrhythmias in LHIS include concomitant coronary artery disease, conducting pathway defects from LHIS, and fibrosis of myocardium from fat deposition[15]. Due to the rarity of the condition, no definitive medical treatment is suggested. Zeebregtset al[15]recommended surgical resection in LHIS patients with altered hemodynamic function leading to congestive heart failure, and those with life-threatening rhythm abnormalities[15].

The long-term prognosis for asymptomatic lipomas is good, but symptomatic lipomas, if left untreated are known to have a grim prognosis. Cardiac lipomas following successful surgical excision have a favorable long-term prognosis[5]. Most commonly noted post-operative complications with cardiac lipoma excision include arrhythmias, pneumonia and bleeding. In addition, cardiac lipoma may recur[16,17].With our patient's unusual tumor features and location in addition to, several comorbidities, surgical resection was proscribed and symptom management with antiarrhythmics showed only limited success. Due to the failure of medical management, ablation provided symptomatic relief and restoration of sinus rhythm for 10 mo post-procedure. With our case demonstrating a successful treatment and no symptom recurrence on follow-up, techniques like transthoracic puncture ablation,radiofrequency ablationetc. as the mainstay of treatment should be investigated further to avoid surgery and its risks. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of cardiac lipoma and LHIS successfully managed with radiofrequency ablation.

CONCLUSION

Cardiac lipoma and LHIS are the infrequent causes of atrial arrhythmias. Cardiac MRI is highly diagnostic in differentiating these lesions and should be considered as a reliable method for diagnosis prior to biopsy. Cardiac lipomas are typically treated with surgical excision due to favorable long-term prognosis. With our patient showing resolution of symptoms with cardiac ablation, we recommend further research in assessing the benefits and risks of various treatment modalities in the management of these lesions.

World Journal of Cardiology2020年6期

World Journal of Cardiology2020年6期

- World Journal of Cardiology的其它文章

- Autonomic neurocardiogenic syndrome is stonewalled by the universal definition of myocardial infarction

- Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries patients: A review

- Diagnostic and treatment utility of echocardiography in the management of the cardiac patient

- lntra-procedural arrhythmia during cardiac catheterization: A systematic review of literature

- Exercise-induced torsades de pointes as an unusual presentation of cardiac sarcoidosis: A case report and review of literature