Predictive value of alarm symptoms in patients with Rome IV dyspepsia: A cross-sectional study

Zhong-Cao Wei, Qian Yang, Qi Yang, Juan Yang, Xin-Xing Tantai, Xin Xing, Cai-Lan Xiao, Yang-Lin Pan, Jin-Hai Wang, Na Liu

Abstract

Key words: Rome IV; Dyspepsia; Alarm symptoms; Prediction

INTRODUCTION

Dyspepsia is a clinical symptom originating from the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Dyspepsia can be divided into functional dyspepsia (FD) and organic dyspepsia. FD is a very common functional GI disorder in clinical treatment[1,2]. It is a clinical syndrome that is characterized by chronic or recurrent gastroduodenal symptoms, without any organic or metabolic disease that may explain the symptoms[3-5]. FD has a high incidence in the population. Dyspepsia is present in approximately 20% of the general population worldwide[6], and a recent study showed that FD was present in 11% of the general population in Italy[7]. FD dramatically reduces a patient’s quality of life, and it also imposes a severe financial burden due to frequent clinical visits, prolonged drug use and long time off work[8,9].

Clinical diagnosis of the underlying cause of dyspepsia based on symptoms alone is believed to be unreliable[10,11], but a range of alarm symptoms are suggested to indicate an elevated risk of serious illness[12]. Alarm symptoms may indicate underlying malignancy or significant pathology, such as a stricture or ulcer[13]. However, according to the results of previous studies, the sensitivity of alarm symptoms to predict upper GI malignancies is not satisfactory[13-15]. The predictive effect of alarm symptoms requires further research.

FD is a type of dyspepsia that has no organic, metabolic or systemic disease to explain its symptoms, but only a few studies have rigorously diagnosed FD by laboratory examination, epigastric ultrasound and upper GI endoscopy to exclude related diseases[16,17], especially in cross-sectional studies. Further research is needed to rigorously diagnose FD through laboratory examination, epigastric ultrasound and upper GI endoscopy.

In 2016, the Rome IV criteria for dyspepsia were introduced. The Rome IV criteria redefined the frequency and severity of each dyspeptic symptom in patients with dyspepsia, but the effectiveness of the Rome IV criteria still needs to be confirmed by relevant studies[18]. At present, no study has assessed the predictive effect of alarm symptoms according to the Rome IV criteria. Here, we carried out a study to evaluate the predictive value of alarm symptoms in dyspeptic patients based on Rome IV.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted at two academic urban tertiary-care centers (the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University and the Affiliated Hospital of Northwest University), which provide medical services to the whole of northwest China from March 2018 to January 2019. Patients who visited the gastroenterology clinics and completed upper GI endoscopy and epigastric ultrasounds during the study period were initially screened. Furthermore, patients with dyspeptic symptoms who met the Rome IV criteria were further selected. Patients who met the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria were eventually included in our study. Oral informed consent was obtained from all included patients. The ethics committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University approved this study. This study protocol was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03479528). In addition, there was no funding received.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age was ≥ 18 years; (2) The chief complaint was dyspeptic symptoms that met the Rome IV criteria (at least one of the following symptoms was present: Bothersome postprandial fullness at least 3 d per week, bothersome early satiation at least 3 d per week, bothersome epigastric pain at least 1 d a week, bothersome epigastric burning at least 1 d a week; symptoms must have been present for at least 3 mo in the previous 6 mo); (3) Patients visited the gastroenterology clinics and completed upper GI endoscopy and epigastric ultrasounds during the study period; and (4) routine blood examination, liver function test andHelicobacter pylori(H. pylori) test were conducted within the last 6 mo (to ensure that these diagnostic tests were conducted after the onset of dyspeptic symptoms).

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria: (1) History of esophageal cancer, gastric ulcer, gastric cancer or other types of organic upper GI disease, disease of the pancreas or biliary tract or metabolic disorders (thyroid dysfunction, diabetes mellitus); (2) Pregnancy, pregnancy preparation, lactation; (3) History of abdominal surgery; (4) Severe nervous system diseases, mental illness or severe liver, kidney, heart or respiratory related dysfunction; (5) Abnormal liver function, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hepatitis B or hepatitis C related hepatitis; (6) Current antidepressant, steroid or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use; (7) Patients only or predominantly had reflux-related symptoms; and (8) Patients who were reluctant to participate in this study.

Data collection

All related data were obtained through a clinic visit and telephone consultation. We collected the basic demographic data (name, age, height, weight, gender, marriage), dyspeptic information (dyspeptic symptoms, duration, frequency per week), alarm symptoms [including weight loss and its extent[19], anemia (hemoglobin < 130 g/L for men and hemoglobin < 120 g/L for women), dysphagia, melena, vomiting, anorexia], lifestyle data (including spicy foods, smoking and smoking amount, drinking and alcohol consumption, sleep quality, daily exercise duration), examination results (H. pylori, upper abdominal B ultrasound, upper GI endoscopy), family history and outpatient cost information. All questionnaire data were imported into the database by a trained researcher.

Definitions of FD

FD was diagnosed strictly by laboratory examination, abdominal ultrasound and upper GI endoscopy. As Rome IV criteria redefined the frequency and severity of each dyspeptic symptom in patients with dyspepsia, the dyspeptic symptoms of the included patients were all severe enough to impact usual activities, and the questionnaire included the frequency of dyspepsia. The presence or absence of Rome IV-defined FD, epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) and postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) were decided by the questionnaire according to the Rome IV criteria[18,20](see Supplementary Table 1). There was no evidence of abnormal results of upper GI endoscopy, epigastric ultrasound, laboratory examination orH. pylori-associated dyspepsia[21,22].H. pylori-associated dyspepsia was defined as the relief of dyspepsia symptoms after eradication ofH. pylori[18].

Definitions of organic dyspepsia

Dyspepsia can be divided into FD and organic dyspepsia. Organic dyspepsia occurs when clinical or laboratory tests reveal underlying organic disease that may be the cause of these symptoms[23,24]. Organic dyspepsia was caused by abnormal results of upper GI endoscopy, epigastric ultrasound, laboratory examination andH. pyloriassociated dyspepsia in this study. We regarded hepatic cyst (< 5 cm)[25], hepatic hemangioma (< 5 cm)[26], fatty liver, gallbladder wall roughness, cholesterol crystal and gallbladder polyps (< 1 cm)[27]as normal epigastric ultrasound, and gallstone was regarded as abnormal epigastric ultrasound. Abnormal routine blood tests (anemia) were regarded as abnormal laboratory examination.

Definition of organic upper GI disease

All patients underwent complete upper GI endoscopy, and the physicians who performed upper GI endoscopy maintained a blind method for data collection. The findings were recorded using the endoscopic reporting system. Researchers reviewed these endoscopic reports and recorded the patient’s endoscopic diagnosis. Upper GI endoscopy or biopsy pathology indicated that organic diseases were classified as organic upper GI disease, while upper GI endoscopy and biopsy pathology showed no evidence of organic disease were classified as nonorganic upper GI diseases. Organic upper GI diseases included gastric ulcer, gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer and esophagus cancer. Endoscopic chronic gastritis and duodenitis are considered nonorganic upper GI diseases[18]. Gastric erosion, duodenal erosion, Barrett's esophagus and esophageal candidiasis were asymptomatic findings and were also regarded as nonorganic diseases of the upper GI diseases.

Statistical analysis

EpiData3.1 software was used to input data, and statistical analyses were performed by EmpowerStats and SPSS 20.0 software. Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and analyzed using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using at-test or Kruskal–Wallis test. Variables were first evaluated with univariate analysis, variables withP< 0.10 in univariate analysis were then included in the multivariate analysis (logistic regression analysis), and exact logistic regression was conducted by SAS software when appropriate. Data were presented with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve to judge the predictive value of independent risk factors.

RESULTS

Baseline of patient characteristics

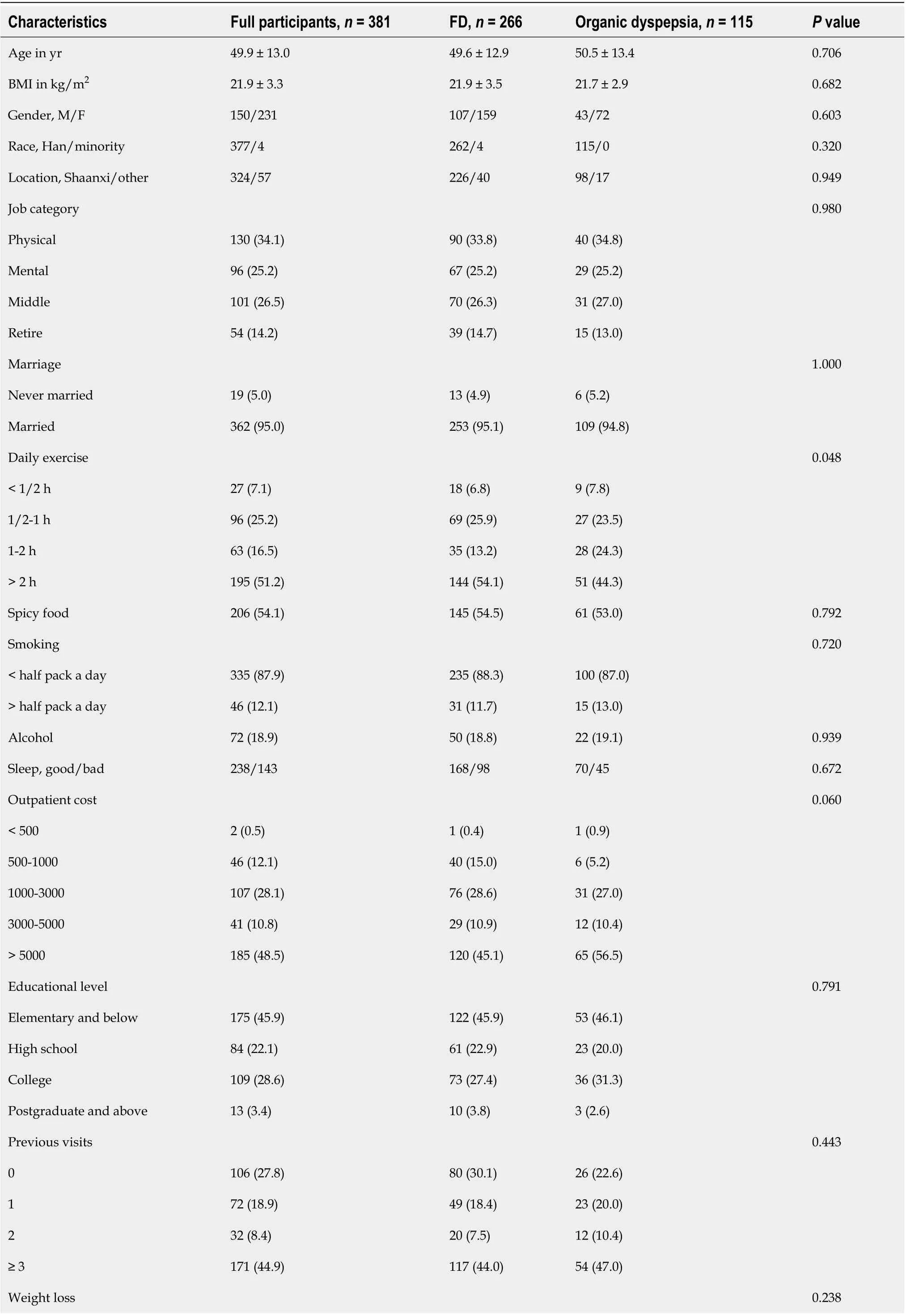

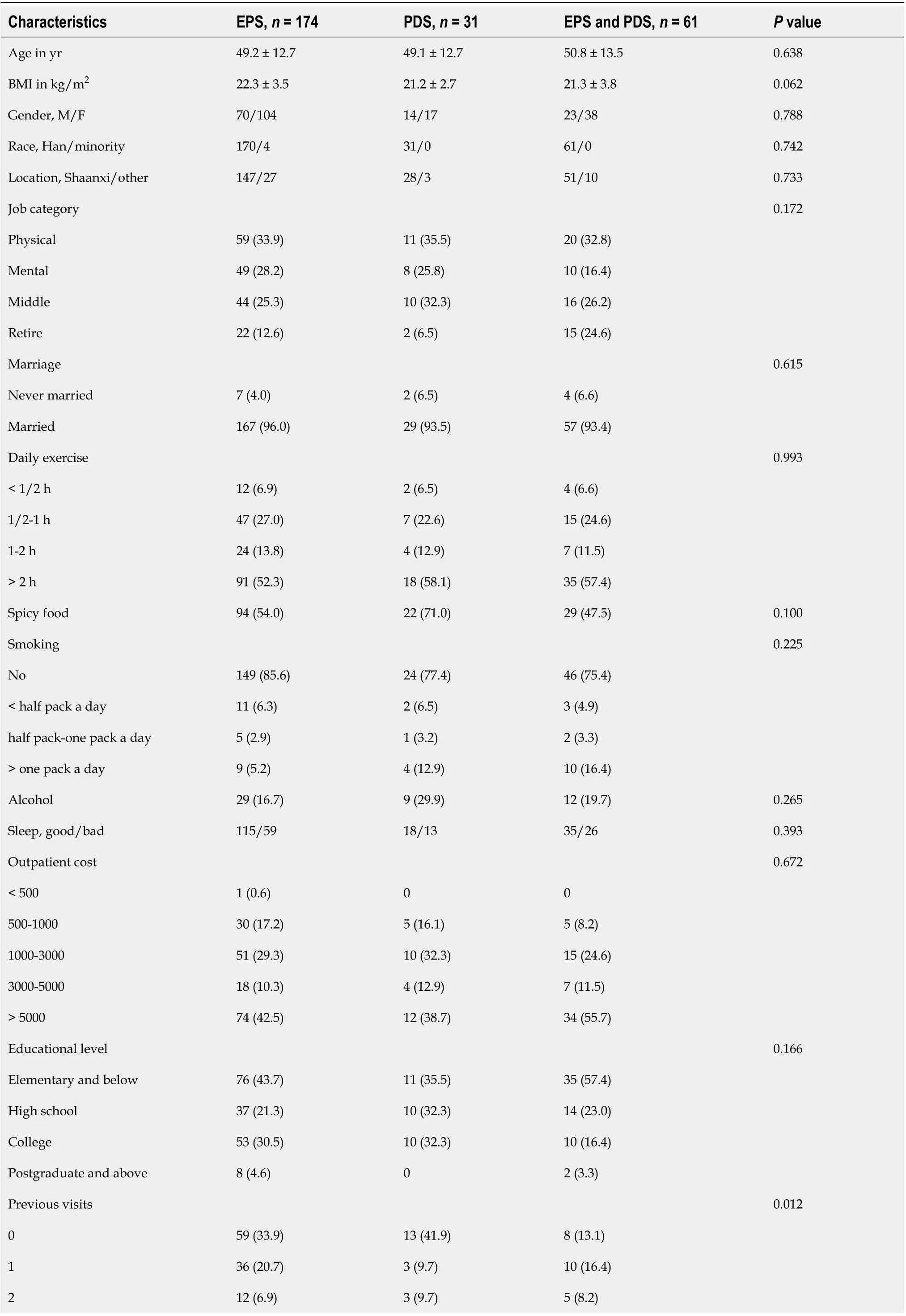

Between March 2018 and January 2019, a total of 381 patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were collected in this study, including 266 FD patients, 115 organic dyspepsia patients and 24 organic upper GI disease patients (Figure 1). The mean age was 49.9 ± 13.0 years, and 231 (60.6%) patients were female. The baseline characteristics of all participants are shown in Table 1. Among the 381 people who met the Rome IV criteria, there were 224 with chronic gastritis, 120 with gastric erosion, 9 with gastric ulcers and 8 with Barrett's esophagus and others. The results of upper GI endoscopy are shown in Figure 2, and the results of epigastric ultrasounds are shown in Supplementary Figure 1. The results of routine blood tests are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

We also randomly selected the upper GI endoscopy results of 200 healthy people from the health examination center of the Affiliated Hospital of Northwest University. The upper GI endoscopy results showed that 77% of patients had chronic gastritis, duodenitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal candidiasis or gastric erosion, indicating ahigh proportion of patients in the general population (Supplementary Table 2). These data further supported our decision to treat chronic gastritis, duodenitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal candidiasis or gastric erosion as functional diseases.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of all participants and univariate analyses of various predictive variables for organic dyspepsia

No 277 (72.7)199 (74.8)78 (67.8)< 7 lb 50 (13.1)30 (11.3)20 (17.4)≥ 7 lb 54 (14.2)37 (13.9)17 (14.8)Anemia, yes/no 31/350 0/266 31/84< 0.001 Anorexia, yes/no 94/287 66/200 28/87 0.923 Vomiting, yes/no 22/359 14/252 8/107 0.485 Melena, yes/no 23/358 16/250 7/108 1.000 Dysphagia, yes/no 3/378 1/265 2/113 0.218 Family history 0.204 None 331 (86.9)235 (88.3)96 (83.5)Esophagus cancer 13 (3.4)10 (3.8)3 (2.6)Gastric cancer 24 (6.3)15 (5.6)9 (7.8)Other 13 (3.4)6 (2.3)7 (6.1)Alarm symptoms 0.004 No 161 (42.3)125 (47.0)36 (31.3)Yes 220 (57.7)141 (53.0)79 (68.7)Number of alarm symptoms 0.001 0 161 (42.3)125 (47.0)36 (31.3)1 139 (36.5)96 (36.1)43 (37.4)2 59 (15.5)37 (13.9)22 (19.1)3 18 (4.7)7 (2.6)11 (9.6)4 4 (1.0)1 (0.4)3 (2.6)Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or n (%). BMI: Body mass index; M: Male; F: Female; FD: Functional dyspepsia.

Figure 1 Flow chart of the study. GI: Gastrointestinal; Hp: Helicobacter pylori.

Prediction of organic dyspepsia

Figure 2 Endoscopy results.

For the comparison between FD and organic dyspepsia, there were 266 FD and 115 organic dyspepsia. In univariate analysis, there were statistically significant differences between FD and organic dyspepsia in daily exercise (P= 0.048), anemia (P< 0.001), alarm symptoms (P= 0.004) and number of alarm symptoms (P= 0.001). Then in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, outpatient cost was analyzed together with daily exercise, anemia, alarm symptoms and number of alarm symptoms. All anemia patients always had organic dyspepsia with complete separation, and exact logistic regression analysis was used. Anemia (OR = 137.700, 95%CI: 30.206-∞,P< 0.001) was still an independent predictor of organic dyspepsia (Table 1). These data suggested that most alarm symptoms had poor predictive value for organic dyspepsia based on Rome IV criteria. Moreover, there was no difference in outpatient cost between patients with FD and those with organic dyspepsia.

Prediction of organic upper GI diseases

There were 266 FD and 24 organic upper GI disease cases. Univariate analysis demonstrated that smoking (P= 0.024), anemia (P< 0.001), alarm symptoms (P= 0.038) and number of alarm symptoms (P= 0.009) were significant predictors of organic upper GI diseases. In multivariate analysis, age together with smoking, anemia, alarm symptoms and number of alarm symptoms were analyzed. Anemia belonged to organic upper GI diseases, there was complete separation, and exact logistic regression analysis was used. In multivariate regression analysis, age (OR = 1.056,P= 0.012), smoking (OR = 4.714,P= 0.006) and anemia (OR = 88.270,P< 0.001) were independent predictors for organic upper GI diseases (Table 2).

Additionally, the receiver operating characteristic curve was used to evaluate the predictive value of these independent risk factors. When the three criteria (age, smoking and anemia) were used together, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.788 (P< 0.001, 95%CI: 0.692-0.884). These data suggested that most alarm symptoms had poor predictive value for organic dyspepsia based on Rome IV criteria, and age, smoking and anemia had certain predictive value for organic dyspepsia. Moreover, there was no difference in outpatient cost between FD patients and patients with organic upper GI diseases.

Comparison of EPS and PDS

FD was prevalent in 266 of the population who underwent complete upper GI endoscopy according to the Rome IV criteria. Among the 266 patients with dyspepsia, 174 individuals only presented with EPS, 31 individuals only met the criteria for PDS, and the remaining 61 individuals presented with both EPS and PDS. For the comparison of EPS, PDS and EPS combined with PDS, univariate analysis showed that there were statistically significant differences in anorexia (P= 0.021) and previous visits (P= 0.012), and the clinical characteristics of patients with EPS, PDS and EPS combined with PDS were not significantly different. Characteristics of patients with EPS, PDS and EPS combined with PDS are shown in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, our study is the first to research the predictive value of alarmsymptoms in patients with Rome IV dyspepsia. For patients with dyspepsia, it is very important to identify early digestive tract diseases, and the ability of alarm symptoms to identify severe upper digestive tract diseases is limited, meaning that further study is necessary[13,19,28]. In this study, patients with dyspepsia symptoms who met the Rome IV criteria were collected to evaluate the predictive value of alarm symptoms for dyspepsia.

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analysis of various predictive variables for organic upper gastrointestinal diseases

Weight loss 0.380 No 199 (74.8)16 (66.7)< 7 lb 30 (11.3)5 (20.8)≥ 7 lb 37 (13.9)3 (12.5)Anemia, yes/no 0/266 5/19< 0.001 88.27 15.486-∞< 0.001 Anorexia, yes/no 66/200 9/15 0.222 Vomiting, yes/no 14/252 3/21 0.156 Melena, yes/no 16/250 3/21 0.200 Dysphagia, yes/no 1/265 1/23 0.159 Family history 0.627 None 235 (88.3)22 (91.7)Esophagus cancer 10 (3.8)0 Gastric cancer 15 (5.6)2 (8.3)Other 6 (2.3)0 Alarm symptoms 0.038 No 125 (47.0)6 (25.0)Yes 141 (53.0)18 (75.0)Number of alarm symptoms 0.009 0 125 (47.0)6 (25.0)1 96 (36.1)10 (41.7)2 37 (13.9)4 (16.7)3 7 (2.6)3 (12.5)4 1 (0.4)1 (4.2)Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or n (%). BMI: Body mass index; M: Male; F: Female; FD: Functional dyspepsia; OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

FD was diagnosed strictly by laboratory examination, abdominal ultrasound and upper GI endoscopy. In the exclusion criteria of our study, we excluded patients with liver dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction and other organic or metabolic diseases that were treated primarily as nondyspeptic diseases in clinical practice. In addition, severe abnormalities of white blood cells or platelets were considered as having other serious diseases and were excluded. Mild abnormalities of white blood cells or platelets were considered as normal results without causing any symptoms. Therefore, abnormal routine blood tests refer to anemia in this study.

In this cross-sectional study, we were unable to determine whether dyspeptic symptoms were relieved after treatment for anemia. As anemia is likely to explain dyspeptic symptoms and FD was diagnosed strictly by laboratory examination, abdominal ultrasound and upper GI endoscopy in this study, all anemia was considered organic disease regardless of whether it was proven to actually be associated with dyspeptic symptoms. Therefore, we not only evaluated the predictive value of alarm symptoms for organic dyspepsia, but also evaluated the predictive value of alarm symptoms for organic upper GI diseases to make the results more accurate. The results of this study showed that anemia was the only independent risk factor for organic dyspepsia and organic upper GI diseases among alarm symptoms based on the Rome IV criteria. Therefore, based on the Rome IV criteria, most alarm symptoms were of limited value in predicting organic dyspepsia and organic upper GIdiseases.

Table 3 Characteristics of patients with epigastric pain syndrome and postprandial distress syndrome

≥ 3 67 (38.5)12 (38.7)38 (62.3)Weight loss 0.637 No 133 (76.4)24 (77.4)42 (68.9)< 7 lb 20 (11.5)2 (6.5)8 (13.1)≥ 7 lb 21 (12.1)5 (16.1)11 (18.0)Anorexia, yes/no 34/140 10/21 22/39 0.021 Vomiting, yes/no 11/163 0/31 3/58 0.535 Melena, yes/no 9/165 4/27 3/58 0.236 Dysphagia, yes/no 0/174 1/30 0/61 0.117 Family history 0.743 None 151 (86.8)28 (90.3)56 (91.8)Esophagus cancer 7 (4.0)1 (3.2)2 (3.3)Gastric cancer 10 (5.7)2 (6.5)3 (4.9)Other 6 (3.4)0 0 Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or n (%). BMI: Body mass index; M: Male; F: Female; EPS: Epigastric pain syndrome; PDS: Postprandial distress syndrome.

A systematic review reported that the global prevalence of FD among adults ranged between 1.8% and 57% according to the Rome criteria used to define FD. Among patients with dyspepsia, more than 70% had FD[29]. In our study, among patients with dyspepsia, the prevalence of FD was 69.8% (266/381) according to the Rome IV criteria, and the rate of patients who were diagnosed with FD was slightly lower. The reason may be that the dyspeptic patients included had completed an upper GI endoscopy, an abdominal ultrasonography, a routine blood examination, a liver function test and anH. pyloritest within the last 6 mo. Many FD patients with incomplete data were excluded.

Our data suggested that age was the independent predictor for organic upper GI diseases (OR = 1.056,P= 0.012). In a study by Gracieet al[30]of the Rome III criteria, the age of organic upper GI diseases patients were older than of FD patients. In a prospective cross-sectional study of 839 patients, there was a significant difference in age between patients with FD and those with organic upper GI diseases[31]. Our research results also showed that, based on the Rome IV criteria, smoking was an independent risk factor for organic upper GI diseases (OR = 4.714,P= 0.006, 95%CI: 1.569-14.16). FD epidemiological data indicated that smoking was a factor associated with the pathophysiology of FD[32]. In an observational study, smoking was an independent predictor of organic dyspepsia, while Faintuchet alshowed that smoking status was associated with organic dyspepsia. Several reports suggested that smoking was a risk factor for gastric or duodenal ulcer based on multivariable logistic regression analyses. Overall, the results in our study were remarkably comparable to those of other studies.

The relationship between clinical features and dyspepsia was not consistent[33-36]. In this study, gender, BMI, race, location, marriage, spicy food, alcohol, sleep, daily exercise, educational level, outpatient cost and previous visits were not independent risk factors for organic dyspepsia and organic upper GI diseases, which may be related to the diverse clinical characteristics and the limited number of patients. No consistent results had been obtained on the relationship between FD and clinical characteristics in previous studies, which still needed to be confirmed by further clinical studies[37-39].

Our study had some limitations. First, in our study, FD was diagnosed strictly by laboratory examination, abdominal ultrasound and upper GI endoscopy. The study inclusion criteria were very rigorous. Although our study was conducted at two centers, the relatively small sample size also limited the evidence strength of the results. The study population was mainly from northwest China. In the future, it still needs to be confirmed by larger sample studies from multicenters all over China. Second, because our study mainly compared FD with organic dyspepsia and FD with organic upper GI diseases, we only counted the number of patients with relief of dyspeptic symptoms after eradication ofH. pylori(H. pylori-associated dyspepsia) as a part of organic dyspepsia but did not further count the number of patients with no relief of dyspeptic symptoms after eradication ofH. pyloriand the rate ofH. pyloriinfection in FD. To our knowledge, no study has been conducted to assess the prevalence ofH. pyloriin FD after excludingH. pylori-associated dyspepsia based on the Rome IV criteria making this a good direction for future research. Third, relevant data on psychological factors were not collected, which might be an important influencing factor and can be the next research direction.

In conclusion, most alarm symptoms had poor predictive value for organic dyspepsia and organic upper GI diseases based on Rome IV criteria, and gastroscopic screening should not be based solely on alarm symptoms. The clinical characteristics of patients with EPS, PDS and EPS combined with PDS were not significantly different.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年30期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年30期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Regulation of the intestinal microbiota: An emerging therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel disease

- High levels of serum interleukin-6 increase mortality of hepatitis B virus-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure

- Simultaneous transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and portal vein embolization for patients with large hepatocellular carcinoma before major hepatectomy

- Endoscopic full-thickness resection to treat active Dieulafoy's disease: A case report

- Efficacy and safety of lenvatinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective,real-world study conducted in China

- Efficacy of a Chinese herbal formula on hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients