Efficacy and safety of lenvatinib for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A retrospective,real-world study conducted in China

Dong-Xu Wang, Xu Yang, Jian-Zhen Lin, Yi Bai, Jun-Yu Long, Xiao-Bo Yang, Samuel Seery, Hai-Tao Zhao

Abstract

Key words: Lenvatinib; Real-world study; Hepatocellular carcinoma; Efficacy; Safety; Treatment

INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer, which is predominantly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), remains one of the most common malignant tumors with approximately 841000 new cases and 782000 deaths annually[1]. Over the past decade, sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor, has been considered the only first-line treatment for patients with advanced HCC (aHCC). Systemic therapies for patients with aHCC are rapidly changing, with some new agents showing clinical efficacy in phase III trials[2]. The REFLECT trial compared sorafenib to lenvatinib and, having setting noninferiority criteria as analytical endpoints, found that the overall survival (OS) for those administered lenvatinib was similar to that for those administered sorafenib[3]. Further subgroup analysis found that lenvatinib significantly improved all secondary endpoints including the objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS) and timeto-progression (TTP), especially in the Asian-Pacific subgroup. Based on these findings, lenvatinib has been approved worldwide and has become an alternative firstline treatment for patients with aHCC[4].

Results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have tended to conflict with realworld studies, perhaps because of the nature of experimental controls and constraints. Therefore, lenvatinib monotherapy should be confirmed as efficacious in clinical practice. To date, Obiet al[5]found that the early therapeutic response rate to lenvatinib reached 40% across a small sample of 16 patients. A further multicenter study conducted in Japan involving 37 participants appears to have confirmed these findings with an ORR of 32.4% and a disease control rate (DCR) of 70.3% at 12 wk[6,7].

However, striving to maximize efficiency while avoiding side effects is proving difficult. More recently, in 2019, Sasakiet al[8]suggested that lenvatinib should be administered to patients with relatively good hepatic functions because these patients are more capable of receiving a sufficient relative dose intensity, which then significantly influences objective responses. Lenvatinib doses are generally determined by a patient’s weight, and in a further related study, Esoet al[9]found that the delivered dose: Intensity/body surface area ratio at 60 d can be an important factor for treatment intensity. In addition, the response to lenvatinib monotherapy has been found to be similar to that of transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and the therapeutic action of lenvatinib in normalizing blood vessels may be more conducive to the treatment of TACE[10,11]. Therefore, TACE and lenvatinib combined may yield more favorable results for patients with aHCC.

The aforementioned studies focused predominantly on Japanese populations; however, there are a number of not so subtle differences between populations. For example, more than 50% of the global burden of HCC occurs in China, with 76% of these patients having been infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV)[12,13]. In the REFLECT study, researchers have also found that lenvatinib efficacy is not identical between etiological subgroups. Therefore, the massive HCC patient population with concomitant conditions in China must be examined to compare differences before developing guidelines. Lenvatinib was formally approved in China in September 2018; however, research focusing specifically on this population under real-world conditions is not readily available. It is well known that HCC patients in Japan generally also suffer concomitant HCV infection, although this is clearly not the case in the Chinese population[13].

In this study, we investigate the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib across a Chinese HCC patient population under real-world conditions. We also attempt to develop predictions using baseline characteristics, tumor biomarkers and gene mutations, thereby incorporating basic medical research with higher levels of evidence. This novel approach was designed to develop an evidence base to guide clinicians and to gain insight into lenvatinib responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This is a retrospective and multiregional study involving Chinese patients diagnosed with aHCC. Participants were routinely attending multidisciplinary team consultations. All patients were fully informed about the objectives of this study and provided formal consent. Data were collected from patients during lenvatinib interventions for a period of one year from December 2018 to December 2019. The study protocol was compliant with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee at Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

A total of 113 patients were initially deemed eligible. Each of these participants had received a confirmed HCC diagnosis using pathological assessment methods or through specific HCC imaging. The initial sample included participants who had not been recommended for hepatic resection, liver transplantation or any other radical ablation. Patients with Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage B (not applicable for TACE or progressed on locoregional therapy) or BCLC stage C, a Child-Pugh score of A-B, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS) of 0-2 were included (please see Supplementary material for details). Following these criteria, we excluded 31 patients who had been treated with lenvatinib combination therapies at the beginning of treatment. Twenty-six patients were also excluded because they had received an additional antitumor therapy including systematic or locoregional therapy while receiving lenvatinib during this study.

Adverse events (AEs) were analyzed across the 56 remaining patients, of whom 54 patients provided complete information for further analysis. All 54 patients included were administered lenvatinib monotherapy until disease progression or until encountering an intolerant adverse event. The study design flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Assessment of efficacy and adverse events

Initial lenvatinib doses were consistent with guidelines, and were administered orally at 8 mg/d when an individual patient weighed < 60 kg and 12 mg/d for those weighing ≥ 60 kg. Regimens may have been interrupted and even discontinued with the occurrence of unacceptable or serious AEs or when tumor progression was not inhibited.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of study population. HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; ORR: Objective response rate; DCR: Disease control rate; PFS: Progressionfree survival; RECIST 1.1: Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1.

Imaging examinations were conducted using enhanced computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or other available imaging technologies every 4-8 wk after initiation of lenvatinib treatment. Changes in tumor size were assessed by two independent specialists using RECIST 1.1 and were categorized as a complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) or progressive disease (PD).

During the observation period, AEs were collected in detail and assessed according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.0). According to the instructions, when grade 3 or more severe AEs occurred, dose reduction took place, or a temporary interruption was commenced until symptoms subsided to pharmaceutically manageable grades 1 or 2.

Further analysis of baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics were systematically collected and included age, gender, serum biochemistry, extrahepatic spread (EHS), tumor occupation, portal vein thrombus (PVT), history of treatment and size of the target lesion. We also recorded combined characteristics including the ECOG-PS, albumin-bilirubin stage (ALBI), Child-Pugh class and BCLC stage by reviewing histories or through calculations using the available evidence. Utilizing these enabled us to analyze potential factors affecting ORR and PFS.

The patients were divided into different subgroups and stratified according to previous treatments, liver occupation, portal vein invasion, HBV and ALBI grades. Concomitant HBV was confirmed by HBV surface antigen testing. ALBI scores were calculated using the following formula: [log10 bilirubin (μmol/L) × 0.66] + [albumin (g/L) × -0.085], and ALBI grade was determined as Grade I = ≤ -2.60, Grade II = > -2.60 to -1.39, and Grade III > -1.39.

Generating effect predictions using tumor serum biomarkers and gene mutations

Patients with stable disease were categorized into three subgroups, which included the following: Diminished tumor size that did not reach the partial response standard (SS), stable disease without any significant tumor size change (ST) and stable disease with a tumor size increase that did not reach the progression standard (SP). SS and PR statuses were clustered into a “shrinking” group in which tumors were contracting in response to treatment. ST, SP and PD statuses were clustered into an “unshrinking” group in which participants were evidently not responding to treatment.

Recording of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) values before and after administration of lenvatinib within 4 wk was conducted to develop response predictions in both the shrinking and unshrinking groups. Gene mutation information was collected from those who had provided samples for next generation sequencing. Genes needed to appear at least twice to be considered for further analysis. Differences in information reflecting gene mutations were calculated for both groups and compared.

Statistical analysis

Baseline data included continuous and categorical variables, which were calculated and presented as the means with corresponding standard deviations or as simple numbers and percentages. Statistical analyses of the differences between variables were conducted using theχ2or Fisher’s exact tests. Two tailedPvalues of less than 0.05 were considered indicative of statistical significance. Five patient characteristics that may have affected ORRs were analyzed using a multivariate logistic regression model. The Kaplan-Meier method was applied to generate PFS curves, and a log-rank test was used to compare PFS curves for different subgroups.

The variables associated with PFS were analyzed using multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis. The results of the multivariate analysis are presented as odds ratios (ORs) or hazard ratios (HRs) with corresponding 95%CI andPvalues. The sensitivity and specificity of diagnostics were calculated to assess their predictive capabilities for tumor changes using AFP values. Mutated gene frequencies were used to construct a gene mutation map of patients with different responses to lenvatinib. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22 andRsoftware (version 3.6.1).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 56 patients were treated with lenvatinib monotherapy until progression of disease. A further two participants were excluded due to a lack of baseline data. Complete analysis was performed using data from 54 patients. Twenty-five patients were diagnosed by the method of specific imaging. The average age was 59 (± 12) years, and 85% (n= 46) were male. Of this total number, 40 patients were HBV positive. The proportion of patients with cirrhosis or portal hypertension was 72% (n= 39) and 54% (n= 29), respectively. Combining serum biochemistry and baseline characteristics resulted in proportions of Child-Pugh class A and B of 81% (n= 44) and 19% (n= 10), respectively (Table 1).

In 28% (n= 15), liver occupation was greater than 50%. Approximately 39% (n= 21) had a PVT, and 33% (n= 18) showed EHS. In terms of treatment history, 11 patients had previously received radiotherapy, 69% (n= 37) received TACE, 39% (n= 21) received radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and 31% (n= 17) received another targeted therapy. The tumor size across all patients was 6.93 cm (± 4.75), and the number of patients receiving doses of 8 mg and 12 mg was 26 and 28, respectively. Approximately 33% (n= 18) were considered to be in stage B, and 67% (n= 36) in stage C, according to the BCLC criteria. In addition, 27 patients were ALBI grade I, 25 were grade II, and two patients were grade III (Table 2).

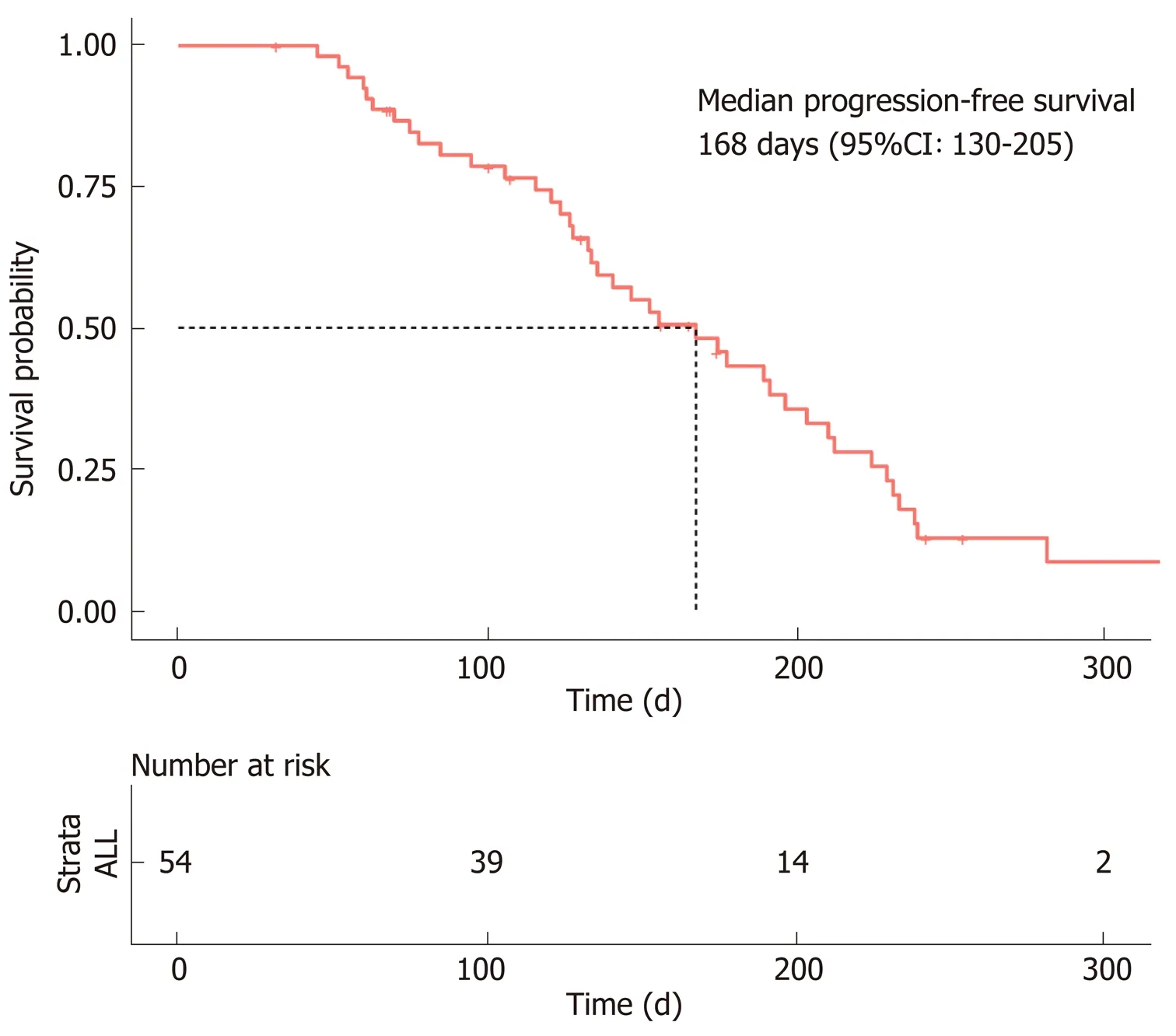

Assessment of efficacy and AEs during entire treatment period

In accordance with the RECIST 1.1 criteria, no patients achieved a CR, a PR was observed in only 12 patients, SD was observed in 36 patients, and PD was observed in six patients. The ORR was 22% (n= 12), and the DCR was 88% (n= 48). The median PFS was estimated to be 5.6 mo (95%CI: 4.3-6.8), and the TTP was 5.1 mo (95%CI: 3.8-6.3) (Figure 2).

Overall survival could not be calculated due to the death rate. Of the patients with concomitant HBV, the number with PR and SD was 10 and 26, respectively, giving an ORR of 25% and a DCR of 90%. The median PFS was 5.8 mo (95%CI: 4.1–7.5), and the TTP was 5.2 mo (95%CI: 4.2-6.2) (Table 3).

Of the 56 patients who continued to be treated with lenvatinib monotherapy, 92.86% (n= 52) developed AEs, and the incidence of grade 3-4 AEs was 21.15% (n= 11). There were no grade 5 AEs. The most common AEs encountered were hypertension in 44.64% (n= 25), decreased appetite in 23.21% (n= 13) and diarrhea in 23.21% (n= 13). Proteinuria was encountered by 21.43% (n= 12) and fatigue by 17.86% (n= 10), followed by hand–foot skin reaction (n= 6), nausea (n= 5), abdominal pain (n= 4), rash (n= 4), decreased weight (n= 3), decreased platelet count (n= 3), hypothyroidism (n= 2), dysphonia (n= 1) and vomiting (n= 1). Complete AE data with percentages are shown in Figure 3.

Among the grade 3-4 AEs, the incidence of proteinuria was the highest, reaching 9.6%, followed by diarrhea (n= 2), hypertension (n= 2), decreased appetite (n= 1) and rash (n= 1) (Table 4).

Table 1 Characteristics of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib

Table 2 Combination characteristics of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib

Multivariate and stratified analysis of ORR and PFS

There did not appear to be a significant relationship between the ORR and the factors analyzed, which were age, gender, HBV infection, first-line therapy, EHS, tumor occupation, PVT, and history of TACE. However, Cox regression analysis suggested that age (HR: 0.95, CI: 0.92-0.99,P< 0.01) and PVT (HR: 0.38, CI: 0.15-0.94,P< 0.037) were significant factors affecting PFS. The median PFS was estimated to be 6.4 mo (95%CI: 4.9-7.8) in 33 patients without PVT and 4.4 mo (95%CI: 3.5-5.3) in 21 patients with PVT (Table 5).

According to our analysis of combined factors, the ORR did not appear to have a significant relationship with ECOG-PS scores, ALBI stages, Child-Pugh classes or BCLC stages. However, changes in PFS were significantly related to patients with Child-Pugh class A or B disease (HR: 0.468; 95%CI: 0.22-0.97;P= 0.042) and BCLCstage B or C disease (HR: 0.465; 95%CI: 0.23-0.93;P= 0.031). The median PFS was 7.0 mo (95%CI: 6.0-8.0 mo) in 18 patients with BCLC stage B disease, 4.4 mo (95%CI: 3.6-5.2) in 36 patients with BCLC stage C disease, 5.8 mo (95%CI: 4.3-7.3) in 44 patients with Child-Pugh class A, and 4.1 mo (95%CI: 0.8-7.4) in 10 patients with Child-Pugh class B (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Table 3 Efficacy of lenvatinib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

Table 4 Lenvatinib-related adverse events in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, n (%)

Therapeutic response predictions based on AFP and gene mutation

As previously described, the “shrinking” group consisted of 21 patients, and the “unshrinking” group consisted of 33 patients. AFP serum concentrations in 56% of patients (n= 30) decreased after treatment. Using this decrease in AFP concentration to predict a reduction in tumor volume, the sensitivity and specificity were calculated tobe 56.7% and 83.3%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 5 Multivariate analysis of the objective response rate and progression-free survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma treated with lenvatinib

Figure 2 Progression-free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients treated with lenvatinib. The median progression-free survival was estimated to be 168 d (95%CI: 130–205 d).

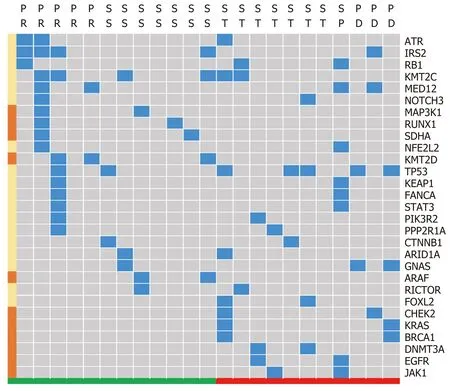

Gene sequence data were only collected from 23 patients, including 13 patients with a reduced tumor size and 11 patients without notable reduction. The high frequency mutations detected wereKMT2C,TP53, andIRS2. Subgroup analysis demonstrated that variations in theCHEK2,KRAS,BRCA1,DNMT3A, andJAK1genes were relatively concentrated in patientswithouttumor reduction, whileSKHA,RUNX1,MAP3K1,KMT2DandARAFgene variations appeared relatively concentrated in patientswithtumor reduction (Figure 6).

Figure 3 Lenvatinib-related adverse events in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. The brown bar represents grade 3-4 adverse events; the blue bar represents all-grade adverse events.

Figure 4 Progression-free survival of patients in different subgroups. BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; PVT: Portal vein thrombus.

Figure 5 Progression-free survival of patients in different subgroups. PS: Performance Status; EHS: Extrahepatic spread.

DISCUSSION

The systematic treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma has dramatically changed over the past two years. To date, sorafenib and lenvatinib have been approved as first-line treatments for HCC; however, in the near future, the TA regimen (i.e., atezolizumab plus bevacizumab), which has a positive effect, will also play an important role in firstline treatments[14]. However, with this novel study design, we hoped to analyze the efficacy and safety of lenvatinib from a variety of aspects. The objective was to develop a more comprehensive understanding of its real-world effectiveness.

By contrast, sorafenib provides an ORR of less than 10%, whereas lenvatinib appears to almost double this rate according to the REFLECT trial (18.8%) and similar real-world studies that have observed ORRs ranging from 20-40% based on the mRECIST criteria[15]. However, to date, few studies have attempted to describe the efficacy of lenvatinib monotherapy in a Chinese population. Furthermore, the apparent differences between HBV and non-HBV cases within this population raise a number of interesting questions. The aforementioned results in our study suggest that HCC carcinoma patients in China, most of whom have HBV infection (40/54), respond positively to lenvatinib (ORR, 22%; PFS, 5.6 mo). However, comparative differences between patients with and without HBV infection are not readily available due to the very limited number of non-HBV infected patients[14]. This result may be consistent with the findings of a meta-analysis conducted by Casadeiet al[16]who highlighted a clear trend favoring lenvatinib over sorafenib (HR, 0.82; 95%CI: 0.60–1.15) in HBVpositive patients.

For patients with BCLC stage B disease participating in the REFLECT trial, Kudoet al[11]found an ORR for lenvatinib of 61.3% with a PFS of 9.1 mo, which are higher than those achieved with any other known molecular targeted agent offered to HCC patients. Interestingly, of the patients with BCLC stage B disease, most were intolerant of chemoembolization or progressed despite previous TACE therapy. This means that most patients had good liver function and were therefore more likely to receive sustained lenvatinib treatment, which is also associated with a more favorable prognosis. However, our study appears to confirm that the mPFS for patients with BCLC stage B disease is significantly prolonged in contrast to patients with stage C. While this appears to provide valuable insight, the outcomes of the multivariate analysis in this study should be interpreted cautiously due to the small sample.

Figure 6 Signature of gene differences based on different tumor size changes. Response standard and partial response were clustered as a group encountering tumor size reduction in response to treatment, which appears green. Tumor size change, progression standard and progressive disease were clustered into a group that did not respond with tumor size reduction, which appears red. The blue block highlights the existence of specific genes, and the left brown block represents the gene that mainly appears in either the tumor reduction or without reduction groups. SS: Response standard; ST: Tumor size change; SP: Progression standard; PD: Progressive disease; PR: Partial response.

Currently, second-line therapy after sorafenib is increasingly being investigated as the majority of patients who initially receive sorafenib also require a second-line or possibly a combined intervention. Hiraokaet al[6,7]found that there was no significant difference in the ORR or DCR between patients who had (or had not) previously received sorafenib. This early evidence perhaps suggests that lenvatinib provides a beneficial therapeutic response not only as a first-line treatment but also as a potential second-line intervention. Seventeen patients were treated with sorafenib in our study, and the multivariate analysis suggested that there was no significant difference in either the ORR (HR: 0.324; 95%CI: 0.055-1.901;P= 0.212) or PFS (HR: 1.724; 95%CI: 0.796-3.734;P= 0.167). These results appear to support the notion that lenvatinib can be used as an alternative second-line therapy; however, confirmatory studies are required.

Patients with ≥ 50% liver occupation and portal vein invasion at the main portal branch were excluded in the REFLECT trial; however, in clinical practice, a considerable number of patients who meet these criteria are treated with lenvatinib. Therefore, to accurately analyze efficacy and identify patients who are most likely to benefit from lenvatinib, we conducted a further multivariate analysis of potentially influential factors. Stratified analysis demonstrated that liver occupation was not a significant factor affecting the ORR (HR: 1.409; 95%CI: 0.353-5.620;P= 0.627) or PFS (HR: 0.779; 95%CI: 0.401-1.514;P= 0.462). In contrast, portal vein invasion potentially affects PFS, although this finding is not completely consistent with a previous study. Hatanakaet al[17]found that a PS of 0 and the presence of both macrovascular invasion and EHS were significant factors affecting overall PFS. The factors affecting both the ORR and PFS are not identical across studies, although these results all indicate that liver function and malignancy are strongly related to patient prognosis. Therefore, protecting liver function to avoid interrupting treatments due to AEs appears to be important for prolonging survival.

In this study, we utilized descriptive statistics rather than correlation analysis between AEs and clinical characteristics because there are a number of factors that could confound our interpretation. For example, Ueshimaet al[18]found that using a Child–Pugh score of 5 and ALBI grade I predict higher response rates and lower treatment discontinuation. However, the attributed ALBI scores were constantly changing during the treatment period, and there was a significant decline in ALBI scores from the baseline, which was observed at 4 and 12 wk after the start of treatment[7]. It is worth mentioning that hypertension, diarrhea, fatigue and decreased appetite were the main side effects in the present study, which are subtly different from those highlighted in the study by Hiraokaet al[6]. The side effects observed here are generally more tolerable than the side effects encountered with sorafenib, which enables clinicians to prolong regimens, thereby increasing the opportunity for patients to respond positively. In addition, we found that albuminuria is particularly apparent in patients with HCC, with a rate of 10% for grade 3-4. This side effect can potentially weaken the patient's PS and cause treatment interruptions. Fortunately, this may well be manageable, if clinicians can preempt imbalanced urinary protein levels and adjust medications in a timely fashion.

AFP levels represent the activity of tumors under certain circumstances, and clinicians usually interpret AFP changes to assist in understanding treatment effects[19,20]. The results of this study suggest that the downward trend in AFP levels from baseline after introducing lenvatinib is a direct response. Upon further analysis, we found AFP to be a potential biomarker for predicting a reduction in tumor volume. In practice, clinicians may be able to adjust lenvatinib treatments by observing changes in tumor sizes in accordance with decreasing tumor markers. However, it is important to be tentative in order to avoid false progression predictions.

Gene sequencing has been used to guide treatment planning in the field of HCC for many years, but identifying predictive genetic markers for lenvatinib treatment is frontier research and has not yet been widely considered[21]. Even though lenvatinib is a multitarget anti-angiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor that can be administered without previously established gene guidelines, this certainly appears to be the next logical step for enhancing the treatment effect of lenvatinib. The inhibitory potential of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) 1-4 in lenvatinib is different to that in sorafenib and is possibly the reason for the observed improvement in the overall effect[22]. In this study, the results of the gene mutation analysis were consistent with the published mutational landscape of HCC[23,24].

For example, in 2017, Finnet al[25]performed a study that focused on tumor gene expression clustering analysis in patients treated with lenvatinib. Patients were divided into three groups by clustering using expression levels of 36 genes involved in angiogenic and/or growth factor pathways. They found that for patients treated with lenvatinib, improvement in overall survival was seen in the group with higher vascular endothelial growth factor and FGF expression[25]. Likewise, we found that mutations associated with the lenvatinib target, particularly FGFRs1-4, were less frequent, which may confirm previous findings[26]; however, further research is required. An issue preventing us from carrying out correlative statistical analyses was the small number of archived tumor samples, but this study suggests some genes (and potentially intervention-related mutations) that might be used to prompt the use of lenvatinib.

While this study had a number of advantages and certainly adds to the current evidence base, it also had some limitations. Even though the research design embedded strict eligibility criteria and patients were from diverse regions of China, this was a retrospective, small-scale study with a limited number of observations, which meant there was a lack of OS data. The results of the multivariate analysis and effectiveness of predictive biomarkers, including AFP values and gene mutations, should be interpreted cautiously. In general, most participants in this study were suffering from HBV-related HCC, and lenvatinib appears effective to some degree, which confirms findings from the phase III REFLECT study. However, further analysis suggests that patients with reasonably good hepatic function may benefit more from lenvatinib treatment. Changes in AFP values and gene sequences may hold the potential to predict responses to lenvatinib during the therapeutic process although further exploratory studies are necessary.

In conclusion, the majority of this Chinese sample suffered from concomitant HBVrelated HCC. Lenvatinib appears effective, which confirms previous findings from the phase III REFLECT study. However, further analysis suggests baseline characteristics, changes in serum biomarkers and gene sequencing may hold the key for predicting responses to lenvatinib. Further large-scale prospective studies that incorporate the collection and analysis of more basic medical science measures are necessary.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年30期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年30期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Regulation of the intestinal microbiota: An emerging therapeutic strategy for inflammatory bowel disease

- High levels of serum interleukin-6 increase mortality of hepatitis B virus-associated acute-on-chronic liver failure

- Simultaneous transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and portal vein embolization for patients with large hepatocellular carcinoma before major hepatectomy

- Endoscopic full-thickness resection to treat active Dieulafoy's disease: A case report

- Efficacy of a Chinese herbal formula on hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients

- Predictive value of alarm symptoms in patients with Rome IV dyspepsia: A cross-sectional study