Trees of Panama:A complete checklist with every geographic range

Richard Condit ,Salomón Aguilar and Rolando Pérez

Abstract

Introduction

Before human intervention, the nation of Panama was nearly all forest,and forest ecosystems in the moist tropics are diverse. The southern end of Central America,morever, falls within a region where plant species richness reaches a global maximum (Barthlott et al. 1996).Because conserving forest ecosystems requires an understanding of their component species,we set out to catalog the tree species of Panama and document their geographic ranges. Even to assemble a list of known species, however, is challenging because botanical knowledge across the Neotropics lags well behind North America, Europe,and China. Where detailed work is done, new species are frequently described and large range extensions are commonplace. Less appreciated is how much taxonomic revision continues,redefining existing species and genera and reidentifying specimens. Our knowledge is expanding greatly, though, thanks to large and readily available taxonomic and specimen databases,and we produce here the most rigorously assembled catalog to date of the tree species of Panama along with the exact range size of each.

We have been studying trees of Panama for 35 years at intensively surveyed research sites using fully censused plots(Hubbell and Foster 1986a;Condit 1998a;Condit et al.2004;Condit et al.2005;Condit et al.2011;Condit et al.2017).Our interest encompasses the entire assemblage of species,from those few that dominate the forest canopy to the hundreds appearing at very low density(Hubbell and Foster 1986b; Condit et al. 1996). The tree census plots,however, beg the question of further levels of rarity. Are there species altogether absent from the plots and, if so,where are they?

Our goal here is to document the full tree flora of Panama and compare it to the tree species found in our 66 fully censused plots (Condit et al. 2019b; Condit et al. 2019c). We advance previous checklists of Panama trees (D’Arcy 1987; Correa et al. 2004) first by using rigorous criteria for defining a tree: woody, free-standing,terrestrial species reaching 3-m tall.These criteria closely match the rules for inclusion in plots (Condit 1998b)and are consistently reported in taxonomic monographs.We explicitly omit any criteria relating to single- versus multiple-stems, often used to separate trees from shrubs,because stem number is seldom and inconsistently reported. We further advance the earlier checklists with many taxonomic updates of the past 20 years.

Once the species list was vetted, we assembled every Neotropical record from large published databases of herbaria,checklists,and plots,producing a range size estimate for every species.This is a substantial step forward for any diverse tropical region. Range sizes for complete tree flora are known for depauperate temperate areas(McGlone et al.2010;Morin and Lechowicz 2011; 2013),but in the Neotropics, existing quantitative analyses are limited to the subsets of species encountered in local studies (Williams et al. 2010; Bemmels et al. 2018; Chacón-Madrigal et al. 2018). With the entire set of ranges, we address several basic biogeographic questions.What fraction of tropical trees are highly endemic, having ranges<20,000 km2?At the other extreme,how widely do the broadest ranges extend? Do range sizes vary taxonomically, i.e. do some families have more narrow endemics than others, and do ranges vary with the height of a tree species?We also report how many tree species in Panama have never been censused in plots.

Methods

A tree checklist

We started with the checklist for the entire Panama flora published by D’Arcy (1987) and updated by Correa et al. (2004). They both provide a code indicating trees and shrubs. To update the list, we consulted first theFlora Mesoamericana,a set of volumes published by Missouri Botanic Garden over the past 25 years that reviews all plant species, grouped by family, throughout Central America. Unfortunately, only 49 of 141 families of Panama trees are completed to date.For the missing families, we consulted first theManual de Plantas de Costa Rica, which is more complete but omits Panama species whose ranges do not include Costa Rica. Between those two major sources, 23 families of Panama trees are not covered (All chapters we consulted from those two multivolume works are cited in Appendix 1). Next, there is aFlora of Panama, published over four decades in separate articles, but all before 1980;we only consulted it for those 23 missing families.Beyond those large sources,we consulted many monographs and other taxonomic treatments of families, genera, or single species (TheFlora of Panamaand all other monographs we consulted are cited in Appendix 2). To establish what species are present in Panama,we relied on the description of geographic range given in monographs.In species for which no monograph asserted a range, we had the previous checklists (D’Arcy 1987; Correa et al. 2004) and then consulted specimen records from the large data sources described below.

We also checked the Panama tree list published by Beech et al. (2017) as the Global Tree Search (Botanic Gardens Conservation International 2019). When we accessed the list (2 Oct 2019), it included 2757 tree taxa in Panama. We rejected 374 as not valid in Panama but added 26 to our list that we had missed. It was missing over 700 species we recognize.

Definition of a tree

Our goal was to employ a rigorous definition of a tree that could allow precise comparison among regions.Published definitions, however, are inconsistent, using height cutoffs from 2-10 m,and vague,indicating that trees usually but not always have a single main trunk (see for example Little and Jones 1980;Allaby 1992;Western Australian Herbarium 1998;Pell and Angell 2016;Beech et al.2017;Missouri Botanical Garden 2020). All definitions omit forms that are largely tropical, such are stilts, stranglers,or clonal palms. Gschwantner et al. (2009) also sought consistency for the purpose of national forest inventories and reviewed a range of definitions but ended up omitting any height and retaining the vague ’typically’ for a single trunk.

We have the additional goal of establishing a checklist of trees that matches species that would be included in our forest inventory plots in Panama, in which free-standing woody stems with diameter at breast height ≥1 cm are censused (Condit 1998b). To match this and to achieve rigor,we elected to omit the routine but always vague criterion of single versus multiple trunks. Instead, we set a strict height criterion of 3 m, a size which nearly always excludes herbs and corresponds approximately to the 1-cm dbh cutoff,but ignored multiple stems.We recognize that by ignoring stem number, species often considered shrubs are included in our checklist,but there is no alternative that allows consistency and precision,because too many species have multiple stems on some occasions.We also omitted epiphytes and lianas, neither of which are included in tree inventories. Most monographs provide for every species a maximum height,the presence of wood, and whether epiphytic or lianoid. When available,we accepted the assertions on growth form and maximum height as stated inFlora Mesoamericana,Manual de Costa Rica,orFlora of Panama.If the expert reported that a species is sometimes epiphytic(or scandent) and other times free-standing,we accepted it as a tree.Likewise,we included species described as herbs sometimes and woody others if tall enough.

This left 19% of the species not appearing in monographs.We already had the assertion as tree or shrub from the Panama checklists for many species,and we accepted those.In new species,not reported in Correa et al.(2004),we consulted individual specimen labels at the Missouri Botanical Garden website(www.tropicos.org/Home.aspx)to determine whether they qualify as trees.As soon as we found one record of a tree or shrub taller than 3 m, we accepted it.In those species,we do not report a maximum height,and they are omitted from analyses based on tree size.

Data sources for individual occurrences

Herbarium records as well as other observations (plots,inventories) provide coordinates of individual trees. We used two different large online data sources to gather such records.The first was the 2018 BIEN database(version 4.1, October 2018; Maitner et al. 2017), the second the Tropicos database from the Missouri Botanic Garden.The BIEN database includes Tropicos plus GBIF (Global Biodiversity Information Facility)and many other sources and thus has many more records,but the direct Tropicos download (http://services.tropicos.org) has more recent records and cleaner taxonomy. BIEN is plagued with errors in taxonomy and range, especially from GBIF and checklists,though of course Tropicos has errors as well.

The BIEN database has the advantage of allowing extraction of all records by country or province.We thus extracted all records in the 46 American countries appearing in BIEN. We excluded, however, all but the eight southernmost U.S. states for practical reasons, since the northern states include an enormous number of records but only 10 species that reach Panama (Canada was included,since there are few records;Puerto Rico appears as a country). From this extraction (18,065,850 records),we only made use of records for tree species in our checklist, then discarded records placed at centroids of countries and duplicated coordinates,leaving 1,008,245 unique species-coordinate records.Limiting the BIEN analysis to our checklist was necessary because the BIEN extraction includes non-trees and because of the many erroneous records in BIEN for Panama:mistakes in taxonomy,identification,location,plus non-native species.

Because BIEN provides a thorough list of plant records in Panama,it provided a tool for adding new species relative to Correa et al.(2004).We checked all BIEN species in genera that are mostly trees and added them to the checklist if we found valid occurrences in Panama.This led us to add 485 tree species,mostly in families not covered byFlora Mesoamericana.In the end,we either incorporated BIEN tree species into our checklist or decided they do not belong in Panama. There were 810 of the latter: tree species appearing in BIEN-Panama but for which there are no valid records in the country(listed in the supplementary data, Condit et al. 2019a). There must be additional erroneous BIEN records outside Panama, but unfortunately,it was impractical to screen those as thoroughly as records in Panama.

Data must be extracted from Tropicos via species names,not via country.We captured data for every name in our checklist,including every synonym we have.From those, we discarded all records outside the Americas,records placed at centroids of countries, and duplicated coordinates, leaving 335,350 unique species-coordinate records.Tropicos is updated often;our data come from a download on 5 Feb 2020.

A feature provided by BIEN but not Tropicos is a column indicating whether a species is native in the given country for every individual record. Unfortunately, this designation is wrong for many species in central Panama,flagging some well-known native species as exotic. After extensive screening, we concluded that it is often wrong in Central America, Colombia, and Venezuela, while it is helpful in Canada, the USA, Mexico, Ecuador, Peru,Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina. Thus, we excluded BIEN records from range calculations when designated as non-native in the latter nine countries but not elsewhere.

Geographic ranges

For every species,we extracted unique latitude-longitude pairs then converted them to kilometers,assuming that a degree latitude = 110.9463 km and a degree longitude at the equator=111.3195 km.Longitude was then corrected with the cosine of latitude,so that,for example,at 30°latitude, a degree longitude = 96.4055 km. We constructed the minimum convex polygon at which each species was observed, subtracting large bodies of water, and calculated its area. This is known as the EOO, or extent-ofoccurrence,and is often reported for tree species(Gaston and Fuller 2009; Morin and Lechowicz 2013). The EOO requires few assumptions and is easy to calculate in poorly known species with few records. We are thus presenting the realized range of each species, as opposed to the potential range.We calculated the range extent separately from the two data sources, BIEN and Tropicos, and a third time after merging them.The two databases are not independent,but this offers some measure of uncertainty about range estimates.

Of the 3043 tree species we found native in Panama,48 had no records in BIEN and eight had no records in Tropicos. Conveniently, those missing sets were nonoverlapping,meaning that by combining the two sources we had at least one record with coordinates for every species.

Narrow geographic ranges

We were particularly interested in rare species,so sought to be as precise as possible about those with range extents<20 × 103km2. As a check for consistency, we examined 50 species whose range was<20 × 103km2according to one source (BIEN or Tropicos) but>50×103km2according to the other, and we examined all their records using the Tropicos web site (http://www.tropicos.org/Home.aspx). In most, errors were easy to spot, and in 80% of the cases, the wider range was correct. We thus decided to focus on narrow-range species using the merged specimen records, BIEN plus Tropicos.

From the merged data, there were 47 species with< 3 locations. For those with two records, the pair was within 10 km with one exception (a likely error inArdisia pulverulenta). Since no polygon could be drawn, we arbitrarily assigned all 47 of those species a range = 10 km2. Because of the political importance of managing rare species, we further considered species endemic to Panama, i.e unknown outside the country.

Plots and inventories

Our own tree data were collected in two ways.Most come from plots, our main research effort in central Panama.Plots are precisely surveyed rectangles inside which every individual woody stem at least 1 cm in diameter was identified,measured,and mapped(Condit 1998b).The earliest plot was a 50-ha rectangle on Barro Colorado Island(Hubbell and Foster 1983; Condit et al. 2017); full data available at Condit et al.(2019c).Since then we have added 65 more plots,most 1 ha in area(Condit et al.2002;Turner et al. 2018); full data available at Condit et al. (2019b).Our second method for surveying trees was an inventory,in which all species present in a small area were noted,but no individuals were counted or measured (Condit et al. 2013; Turner et al. 2018). All plots and inventories together comprise a list of tree species with the exact locations observed (at a precision of 2 m in plots, 500 m in inventories).

Plot occurrence and range

We thoroughly matched all taxonomy in the checklist and the plots, so it was straightforward to count plot and inventory occurrences for all species in the Panama checklist.We tested whether species found within plots differed in range size from non-plot species using at-test after log-transformation.

Tree height,taxonomy,and range

Based on the maximum height recorded from monographs,we tested whether taller species had wider ranges,simultaneously estimating family differences in range size. We used untransformed height as the predictor of log(range size)in a multi-level regression in which family was a random effect;parameters were estimated using the Metropolis algorithm in a Bayesian hierarchical framework(Condit et al.2007;Condit et al.2017),running the algorithm for 10,000 steps and discarding the first 2,000.Convergence was checked visually. Statistical inference was based on credible intervals for each family for the estimated median range size at 10 m or 30 m tall,using 95thpercentiles of 8,000 parameter values from the Markov chain.The regression was repeated with alternative range estimates(BIEN,Tropicos),but results barely differed and we report only that from merged range sizes.

Data available

A supplementary data archive shows additional results and complete data tables for download (Condit et al.2019a).These include the full species list with range sizes,all synonyms we located for each name, plus the entire table of coordinates from both BIEN and Tropicos.

Results

The flora

We identified 3043 tree species in Panama and recorded a maximum height for 2461 of those: 1418 (57.6%) were≥10 m in height and 417(16.9%)were <5 m tall(Table 1).Extrapolating those percentages to the entire 3043 species leads to 1753 tree species ≥10 tall,774 species 5-10 m tall,and 516 species 3-5 m tall. About 84 of the 3043 species barely qualify as trees, meaning they were described occasionally as a tree but often as non-tree forms (23 lianas,42 herbs,19 epiphytes).A downloadable electronic supplement includes all the species, their families, taxonomic authorities, heights, and recent Latin synonyms(Condit et al.2019a).

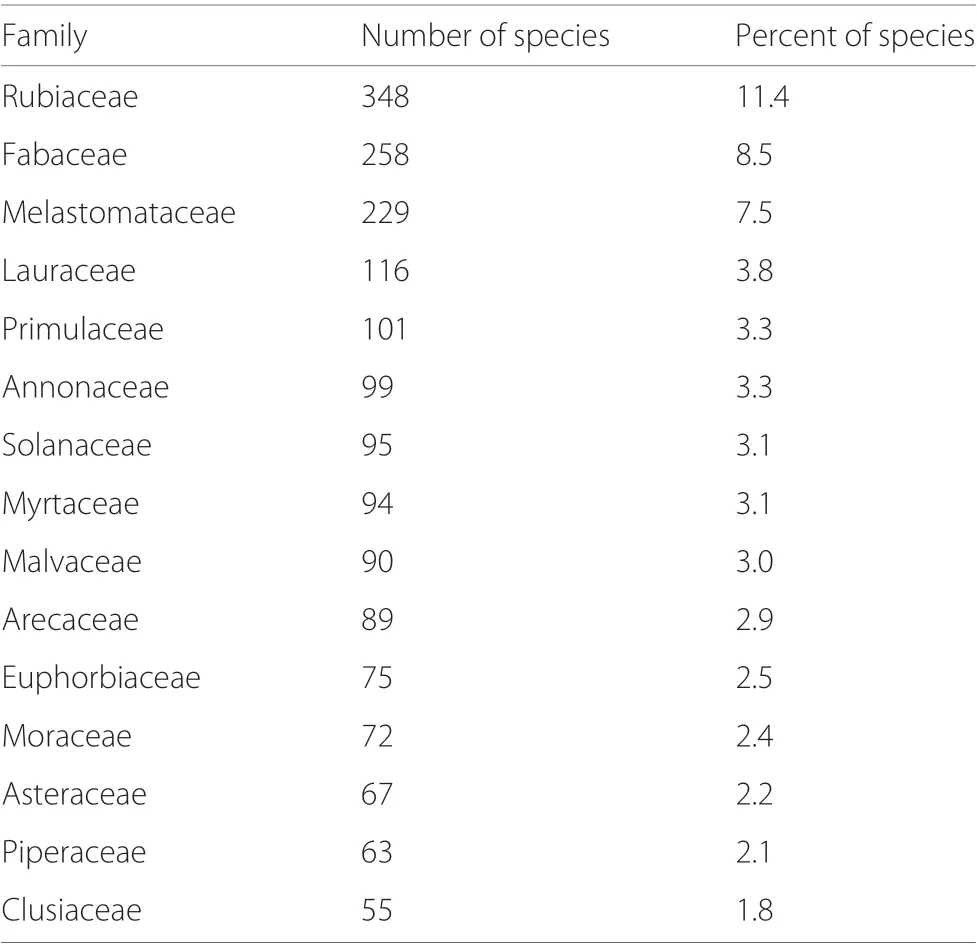

The 3043 species represent 141 families and 752 genera.The biggest family was Rubiaceae with 348 species,or 11.4%of the tree flora,followed by Fabaceae then Melastomataceae (Table 2). The biggest genera wereMiconiathenPalicourea(Table 3).

Range sizes

A few species (2%) had ranges>1.5 × 107km2,but none reached 2 × 107km2(Table 4). Those are ranges from the Americas, however, and a few species extend into the Old World so their full ranges would be higher (Sambucus nigraandDodonaea viscosaoccur widely in the Old World, andCeiba pentandrain Africa). Another 10% of the species had ranges 1×107-1.5 × 107km2(Fig. 1). Some of thewidest ranges reached both 30°S and 30°N latitude,and species with ranges well south also tended to occur far to the north(Figs.2,3).Several of the widest ranges belong to weedy and human adapted species (Psidium guajava,Lantana camara, Manihot esculenta), but those in Fig. 1 are tree species found in undisturbed forest.

Table 1 Panama tree species by maximum height

The histogram of range-size across all 3043 species resembled log-normal to the left of a broad mode at106km2, with a long tail of small ranges (Fig. 4). To the right of the mode, however, ranges were concentrated at an abrupt ceiling just above 107km2. The 55%with ranges<106km2were for the most part confined to Central America or northwest Colombia (Fig. 5). A total of 876 (28.8%) of the tree species had ranges limited to Nicaragua,Costa Rica,Panama,and northwestern Colombia(>4.5°N,<75°W).

Table 2 Twenty most speciose families among trees of Panama

Table 3 Twenty most speciose genera among trees of Panama

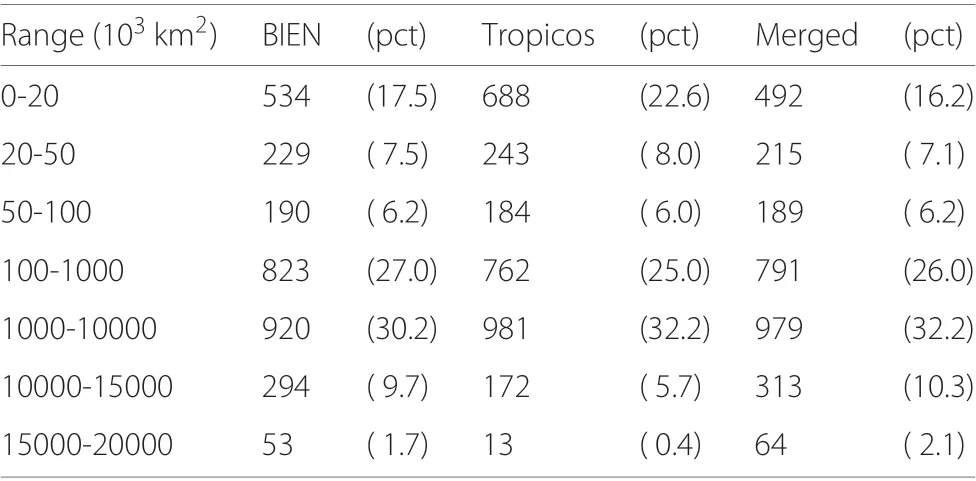

The narrowest ranges included 492 tree species extending over<20 × 103km2, or 16.2% of the tree flora(pooling BIEN and Tropicos, Table 4). This included some seldom observed species, including 15 having only one record and 32 with two records. But therewere 288 species with at least 10 records and a range<20 × 103km2(Table 5). Those 492 narrow-range species included 274 endemic to Panama, 170 shared only with Costa Rica,and 34 shared only with Colombia;a few reached Nicaragua.There were 10 species endemic to Panama with ranges exceeding 20 × 103km2, bringing to 284 the total endemic to Panama (Table 5).Figure 6 shows sample distribution maps of narrow-range species.

Table 4 Range sizes of Panama tree species comparing three data compilations

Results from BIEN data without Tropicos differ little from the full merged data,but using Tropicos data alone led to narrower ranges,as indicated by considerably more species with ranges<20×103km2and fewer species with ranges>107km2(Table 4). Regardless of which set of data were used,the number of species in the center of the histogram,20×103km2to 107km2,was similar(Table 4).

Plot occurrence

We identified 836 of Panama’s tree species in the 66 plots,or 27.5%of the tree flora.An additional 215 species were observed in inventories,so 1051 species(34.5%)appeared in our surveys.Those found in plots were a biased sample of range sizes,lacking the narrow end of the distribution(Fig.4).Of the 836 species found in plots,just(4.5%)had ranges<20×103km2, compared to 20.6% of the 2206 species never encountered in a plot.At the other extreme,22.1% of those plot species had wide ranges,>107km2,compared to 8.7%of the non-plot species,and the median range size of plot species was six times higher than that of non-plot species (Fig. 4). Those results were based on the merged records, but differed little whether BIEN or Tropicos were used.

Taxonomy,tree height,and range

Range size was positively correlated with tree height(Fig. 7). This has a substantial effect on the proportion of narrow-range species: among species with maximum height <5 m,23.7%had ranges<20×103km2,while of those ≥10 m tall,only 9.0%had small ranges.Most families showed the same pattern, but there were significant differences among families. For example, at the smallest heights, Annonaceae, Primulaceae, and Myrtaceae had median range extents of 104km2, while Fabaceae and Moraceae had medians of 106km2(Fig.7),and the fitted median range at 10 m tall varied significantly among families (Fig. 7). Supplemental results show fitted ranges at heights of 10 and 30 meters for all families and show the significant differences.

Discussion

Table 5 Tally of rare species by the number of individual records(N)from which they are known

With over 3000 tree species, Panama has much higher diversity than temperate tree flora. For example, Morin and Lechowicz(2013)found 598 species in North America,and McGlone et al.(2010)reported 582 trees species in North America ≥6 m tall,as well as 215 species in New Zealand and 186 in Europe. Our tally of 3000 includes shrubby species, but by recording maximum heights, a precise comparison is possible: Panama has 2290 tree species ≥6 m tall(1851 with known height,the remaining extrapolated from those with unknown height).Panama’s diversity, however, is not exceptional for the wet tropics.The Malay Peninsula has 3100 tree species in an area similar to Panama’s(Kochummen et al.1992),and Amazonia has about 15,000 tree species(ter Steege et al.2015).The known flora of Panama, excluding ferns, is over 10,000 species (Correa et al. 2004), so trees make up more than a quarter.Contrast this with North America,where there are fewer than 1000 tree species out of a flora of 15,000(Ulloa et al.2017).

No tropical region has fully documented tree ranges,but we can compare range sizes in Panama with North American trees, for which estimates from detailed range maps are often calculated (Little Jr. 1971). Morin and Lechowicz (2011) present ranges in a histogram comparable to Fig. 4. The breadth of the distribution is similar, but the Panama histogram is so truncated near the maximum that it loses the log-normal form characteristic of range sizes (Morin and Lechowicz 2011; Ren et al. 2013). Panama thus has excess wide ranges, those reaching across the Neotropics to both 30°N and 30°S or beyond. Olmstead (2012) found that range limits of tropical lineages often reached both north and south to 35°latitude, and they linked this to the coldest monthly mean temperature of 10°C. Those latitudes reach from the southern USA to southern Brazil, covering nearly 2×107km2and delimiting the widest ranges of Panama’s trees.

At the other extreme, Panama has many narrow range tree species, but the histogram in Morin and Lechowicz(2011)also extends close to a minimum of 10 km2.Reading from their histogram,there are 65 species(11%of the flora) with ranges less than 20,000 km2in North America. Among all Panama trees at least 3 m tall, we report 16%with comparable ranges,but if we consider only those 1851 known to be taller than 6 m, we find 195 species(10% of the flora). It thus appears that the frequency of narrow range trees in Panama does not differ from North America when height criteria match. This counters general wisdom about the high frequency of species with very small ranges in the tropics. Barthlott et al. (2005) and Linares-Palomino et al. (2011), for example, both tally >40%of vascular plants as endemic to biogeographic zones of Central America similar in size to Panama. But these refer to all plants, not just trees. With rigorous comparisons using similar plant groups, it may simply not hold that the neotropics are home to an unusual concentration of narrow endemics.

Another consideration in broad comparisons is taxonomic.There are remarkable differences among families.One pair offers a striking example:among the Primulaceae(formerly the Myrsinaceae in the tropics), there are 101 tree species in Panama and 40 have ranges <20,000 km2,but of 66 Moraceae, there is not a single range size so narrow. We have to wonder how much of the variation between families is due to the specialists, which nearly always differ between taxonomic groups, and their inclination toward lumping versus splitting off new species.

In addition, we need to be careful about comparisons based on ranges of species represented in tree plots(Bemmels et al. 2018; Chacón-Madrigal et al. 2018). Our network of 66 tree plots crossing a climatic gradient in central Panama captured 27%of the tree flora of Panama,but only 7.5%of the narrow endemics.Plots thus provide a highly biased picture of range size.In retrospect,this should not be surprising,since the narrowest ranges are easily missed by plots whereas wide ranges will not be.

An important caveat to bear in mind is that Panama remains poorly known taxonomically and ecologically,and any range size estimate should be considered uncertain. Gentry (1992) described many cases where species once thought to be highly restricted were later discovered thousands of kilometers away,and we observed this often.As one example,Tapirira rubrinervisis on the red list for Ecuador’s trees based on its tiny range there(León Yánez et al. 2011), but now it is known from western Panama to Peru.On top of these extensions,we are working with many newly described species, typically known from one location (e.g. Maas et al. (2019); Santamaría-Aguilar et al.(2019)were published as we prepared this).Plus there are simple errors in identification, sometimes revealed by experts reversing each other (Morales and Zamora 2017; Garwood et al. 2018). We attempted to display some degree of uncertainty by presenting range calculations made with BIEN data versus Tropicos data,both widely used datasets that form the basis of many geographic studies. These give, for example, quite different counts of narrow-range species, but on the other hand,broad patterns of range sizes across the tree flora are similar,and both sources show at least 16%of tree species with ranges below 20,000 km2.

Conclusions

The nation of Panama,with 78,000 km2of mostly forested land,has over 3000 tree species.This is based on a rigorous definition:all free-standing,terrestrial,woody plants at least 3 m tall. By tallying the maximum height known for those species, we conclude that 1753 are large trees,at least 10 m tall.Using readily available online sources of herbarium records, we calculated a geographic range for every one of those trees.The widest-ranging occur across the neotropics, over 1.5 × 107km2, while 15 species are known at only one location.

In tropical flora,the species range size is nearly always the basis of conservation assessment because no other information is available. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature red list of trees(Newton and Oldfield 2008) includes 6000 species, or 10% of the world’s flora (Beech et al. 2017). We identified 492 tree species that occur over <20,000 km2, a range often signaling a status of endangered according to IUCN standards. An important step forward for these tree species, all poorly known, will be to estimate population sizes and make demographic assessments of extinction risk. Our tree plots in Panama offer details on local populations for 38 of those potential red-listed trees,and our next step is to assess the population size of those species.

Supplementary information

Supplementary informationaccompanies this paper at https://doi.org/10.1186/s40663-020-00246-z.

Additional file 1:Supplemental Figures

Acknowledgements

We thank Robin Foster for initiating a tree species list in Panama and as our mentor in the ecology and botany of Panama,and we thank the staff of the Center for Tree Science at the Morton Arboretum for expert advice on tree conservation.

Authors’contributions

RC directed plot censuses and inventories,assembled and analyzed the data,and wrote the paper;RP and SA did field work identifying and collecting species and supervising plot censuses,and they commented on the manuscript.The author(s)read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The Center for Tree Science at the Morton Arboretum provided financial support for the lead author.Funding for various phases of the work was provided by the Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation(US).

Availability of data and materials

A supplementary data archive shows additional results(Condit et al.2019a).All species names,synonyms,and the full data,including all individual records and estimated range sizes,are available there for download.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research involved no human subjects.Permission from owners was always obtained for working in parks or on private land in Panama.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author details

1Morton Arboretum,4100 Illinois Rte.53,Lisle,IL 60532,USA.2Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute,Panama City,Panama.

Received:13 December 2019 Accepted:7 May 2020

- Forest Ecosystems的其它文章

- Soil-plant co-stimulation during forest vegetation restoration in a subtropical area of southern China

- Addressing soil protection concerns in forest ecosystem management under climate change

- Species richness,forest types and regeneration of Schima in the subtropical forest ecosystem of Yunnan,southwestern China

- Effects of afforestation of agricultural land with grey alder(Alnus incana(L.)Moench)on soil chemical properties,comparing two contrasting soil groups

- Delineating forest stands from grid data

- Tree diversity effects on forest productivity increase through time because of spatial partitioning