淡水生态系统中几种大DNA病毒研究概述

张奇亚

(1. 中国科学院水生生物研究所淡水生态与生物技术国家重点实验室, 武汉 430072;2. 中国科学院种子设计创新研究院, 北京 100101)

为满足全球日益增长的人口对优质蛋白质的需求, 水产养殖业正快速发展[1,2], 且中国水产养殖的成功经验已提供给全球共享[3]。但仍面临动物种类多、养殖密度大、在多变或劣质水环境中易受流行病侵染的困扰[4]。尤其是病毒引起的水产动物疾病, 发病快、死亡率高、传播广、危害大, 尚无特效药物与解决方案, 被认为是水产养殖业发展的限制因素之一[5—7]。而深入认识病毒病原本质特征, 则成为有效检测、预防控制水产动物病毒病的关键[6,8—11]。

具有双链DNA基因组、其分子量接近或大于100 kb的病毒通常被称为大DNA病毒(或核质大DNA病毒, NCLDVs)[12,13]。包括感染动物的痘病毒科(Poxviridae)、虹彩病毒科(Iridoviridae)、鱼蛙疱疹病毒科(Alloherpesviridae)、线头病毒科(Nimaviridae)、非洲猪瘟病毒科(Asfarviridae)、杆状病毒科(Baculoviridae)和囊泡病毒科(Ascoviridae)成员,感染真核藻的藻类DNA病毒科(Phycodnaviridae)成员, 感染原核藻或蓝藻菌的肌尾病毒科(Myoviridae)成员, 感染原生生物的拟菌病毒科(Mimiviridae)、马赛病毒科(Marseilleviridae)、潘多拉病毒科(Pandoraviridae)、阔口罐病毒科(Pithoviridae)成员等[14]。水生大DNA病毒变异率虽比RNA病毒要低, 但它们的宿主范围及分布环境极广, 存在于各种水体和沉积物中[15—17]。已开展针对大DNA病毒的遗传进化及其宿主适应性的研究[18—21], 其中有感染水产动物重要的病毒病原, 如: 虹彩病毒(Iridoviruses)、疱疹病毒(Herpesviruses)、线头病毒(Nimaviruses)[22,23]和感染蓝藻菌的肌尾噬藻体(Myovirus)[24]。近期查明水环境中大DNA病毒和巨病毒(Giant viruses)的部分基因来源于宿主[25], 且能增加病毒对宿主的适应性[26]。相关研究不仅拓宽病毒知识的边界, 也将促进水产动物病毒病远程诊断、生物调控等智慧渔业水平的提升。

中国科学院水生生物研究所(简称中科院水生所)对鱼病防控及鱼池控藻的研究始于20世纪50年代, 由倪达书负责成立鱼病工作站, 并在苏、浙、粤等省展开鱼病调查[27]。同时, 饶钦止[28]研究和报道了消灭鱼池微囊藻湖靛(水华)的有效方法。20世纪70年代后期, 陈燕燊等[29]则对草鱼出血病病毒病原开展研究, 以集体署名方式在《水生生物学集刊》上发表相关结果。1996年, 《水生生物学报》报道了我国分离鉴定的第一株水生脊椎动物大DNA病毒——沼泽绿牛蛙蛙病毒(Rana gryliovirus,RGV)的相关研究[30,31](图 1), 并由此开始两栖类以及鱼类虹彩病毒的研究, 内容涉及病原的分离鉴定和基因组测序, 如: 鱼淋巴囊肿病毒中国株 (Lymphocystis disease virus-China, LCDV-C, AY380826)[32]、牛蛙蛙病毒RGV (JQ654586)[33]和大鲵蛙病毒 (Andrias davidianusranvirus, ADRV, KC865735)[34]; 确定病毒在宿主体内或细胞中的分布与定位[35], 比较不同毒株主要结构蛋白基因的异同[36]; 鉴定一批功能基因[37—41], 并阐明它们在病毒复制中的作用, 新建双荧光标记可控基因表达重组病毒技术[42]; 揭示几种大DNA病毒与水产动物宿主相互作用的分子机制[43]。病原体》(Ranaviruses: lethal pathogens of ectothermic vertebrates)的撰写[46]、获湖北省自然科学奖的“重要水产动物病毒病原的鉴定及致病机理研究” (2004Z-034-2-010-007)和“水产动物不同病毒基因组解析及病毒与宿主相互作的用分子机制”(2017Z-023-2-010-008)等工作, 记录和见证了“水生病毒学”新枝萌发的过程。中科院水生所报道的蛙病毒RGV[31,33]、大鲵蛙病毒ADRV[34]及淋巴囊肿病毒LCDV-C[32], 中山大学报道的鳜鱼传染性脾肾坏死病毒ISKNV(AF371960)[47]和虎纹蛙病毒TFV(AF389451)、国家海洋局报道的大黄鱼虹彩病毒LYCIV(AY779031)[48]、中国水产科学研究院黄海水产研究所报道的大菱鲆红体病虹彩病毒TRBIV(GQ273492)[49]及新加坡石斑鱼虹彩病毒SGIV(AY521625)[50]等作为虹彩病毒参考毒株, 被2020年更新发布的《国际病毒分类委员会报告》(The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, ICTV Report)收录[51,52], 为大DNA病毒种群共性特征提供借鉴[53]。

图1 蛙病毒RGV引起的蛙致死性出血综合症及其负染电镜图(黄晓红 图)Fig. 1 Rana grylio virus (RGV) caused frog disease with lethal hemorrhagic syndrome and negative staining electron micrograph of the ranavirus particles. Bar=200 nm

尽管人类病毒性疫病会引起公共卫生挑战, 甚至引发全球政治经济格局变化[54,55], 但病毒的感染与毒性有特定宿主范围[56,57]。现有研究表明, 水生病毒仅感染低等脊椎动物与其他水生生物, 尚无鱼类病毒会感染人类的直接证据。水产品是人类安全和高质量蛋白质的重要来源。世界动物卫生组织 (OIE)指出: 水产养殖的好处是无穷的[58]。水产健康养殖能更好地促进水产动物、水环境与人类的整体健康[59]。水生病毒学当前的重点任务就是要在阐释病毒本质及其与宿主和水环境相互作用的基础上, 降低水生动物发生病毒病的风险, 并借助噬藻体等蓝藻菌病毒优化水生态系统, 促进生态健康的水产养殖业可持续增长[9]。

1 研究动态

历经半个世纪, “水生病毒学”学科已发展成水生生物学的特色学科之一。《水生病毒学》与中英文双语专著《水生病毒和及水生病毒病图鉴》[44,45]、由国际知名蛙病毒专家、美国Chinchar和Gray教授为主编的英文专著《蛙病毒:变温脊椎动物的致命淡水大DNA病毒在形态、基因结构、进化及生态作用等方面都具有多样性[21,60,61]。本节主要就两栖类蛙病毒、鲫疱疹病毒、克氏原螯虾(小龙虾)线头病毒及蓝藻菌噬藻体这几种淡水大DNA病毒的研究动态做一简介。

1.1 沼泽绿牛蛙蛙病毒(Rana grylio virus, RGV)和大鲵蛙病毒(Andrias davidianus ranavirus, ADRV)

蛙病毒是能感染世界各地养殖和野生水生动物、有囊膜、基因组大小105—150 kb、直径为100—200 nm的球形大DNA病毒[62], 已测全基因组序列的蛙病毒毒株超过22株[52]。在同一物种中分离到不同蛙毒株的事件也时有发生, 如从牛蛙中分离鉴定了RGV-9506、RGV-9807、RGV-9808等毒株[36]; 而从发病大鲵中分离鉴定CGSIV-HN1104(KF512820)[63]、ADRV’(KF033124)[64]及未分类毒株(KC243313)等。蛙病毒还能跨种感染不同水生动物[65,66]。因此, 专家呼吁要重视并避免这类病毒病传播[67]。

大鲵细胞系的建立与蛙病毒研究已建立的鱼类细胞系现超过300个[68—70], 与之相比, 两栖动物细胞系则要少得多, 并限于无尾(如蛙类)动物细胞系[71—73]。直至2015年, 由中科院水生所建立大鲵胸腺细胞系(Chinese giant salamander thymus cell line, GSTC)、大鲵脾细胞系(Chinese giant salamander spleen cell line, GSSC)及大鲵肾细胞系(Chinese giant salamander kidney cell line, GSKC)之后, 方见有尾动物(如大鲵)细胞系用于科研的报道[74]。其中, GSTC也是源于两栖动物胸腺组织的第一株细胞系。分别测试大鲵胸腺细胞系GSTC、爪蟾肾细胞系A6及鲤上皮瘤细胞系EPC这三种来源不同物种的细胞系对大鲵蛙病毒ADRV的敏感性。引起GSTC细胞病变所需时间最短、病变程度最严重、病毒滴度最高,TCID50达108/mL, 显示GSTC细胞对ADRV很敏感。再用带绿色荧光蛋白标记的重组牛蛙蛙病毒(rRGV)感染, 不仅很快形成空斑, 且与rRGV产生的绿色荧光信号相吻合[75]。可见, GSTC不仅可用于测试蛙病毒感染, 也可用做蛙病毒基因扩增、表达及与宿主相互作用研究的工具[76]。

重组蛙病毒构建及其应用推导蛙病毒基因组可编码95—162个基因, 其中仅三分之一可利用序列同源性推定功能, 而对蛙病毒与宿主相互作用基因则知之甚少[77]。病毒重组技术是研究基因功能的重要技术之一, 还可用于筛选免疫活性分子、基因表达调控及疫苗研发[78]、模拟病毒入侵宿主过程和提供病毒与宿主之间相互作用的研究模型[79]等。基于对蛙病毒RGV尿嘧啶脱氧核糖核苷三磷酸酶基因RGV-dUTP(RGV-67R)[80]、淋巴囊肿病毒-中国株胸苷酸合成酶基因LCDV-CTS(LCDV-C11L)的鉴定[81], 以蛙病毒RGV的胸苷激酶基因TK(RGV-92R)和囊膜蛋白基因(RGV-53R)作为外源基因靶点,构建荧光报告基因或缺失特定基因位点重组病毒[82],获得既保留亲本毒株生物学特性, 又携带外源基因的几种重组蛙病毒[42,83,84]; 还构建可调节特定基因表达、含乳糖操纵子和双荧光标记的条件致死型重组蛙病毒[85]。能否成功构建重组病毒, 选择适合的外源基因插入位点很重要[86]。

蛙病毒功能蛋白的鉴定有囊膜病毒可借助囊膜受体识别分子与细胞受体结合, 介导病毒内吞进入宿主细胞[87]。为查明蛙病毒囊膜蛋白在入侵时有何作用, 选择与蛙病毒属成员有高度同源性的膜蛋白RGV-43R进行分析。结果显示, 该蛋白跨膜结构域决定其在胞质中的定位; 而缺失基因43R的重组蛙病毒∆43R-RGV与野生型RGV相比,前者DNA复制及超微形态不受影响, 但使细胞病变程度及病毒滴度却显著降低, 表明该蛋白是蛙病毒入侵的关键蛋白[88]。

病毒核心蛋白(Core proteins)指不同种属毒株之间高度同源、涉及结构及与复制的病毒蛋白。虹彩病毒科成员有26个核心蛋白[89], 其中, 蛙病毒蛋白RGV-63R被推导为DNA聚合酶, 具有3′-5′外切酶结构域和DNA聚合酶B家族催化结构域。研究揭示该蛋白不仅与病毒加工厂共定位, 还能与作为增殖细胞核抗原(Proliferating cell nuclear antigen,PCNA)的RGV-91R蛋白相互作用, 当这两个蛋白单独或共同过表达时, 均能促进蛙病毒RGV在不同来源细胞系中复制[90]。对大鲵蛙病毒ADRV-96L蛋白进行分析, 显示这是一个具有ATPase活性、促进宿主细胞增殖和生长、有助于产生更多子代病毒[91]的重要蛋白。测试两种蛙病毒的同源核心蛋白RGV-27R和ADRV-85L, 结果显示它们不仅能在两栖动物细胞中高效表达, 且都具有相同的抗原特性[92]。

蛙病毒与宿主的相互作用靶向破坏病毒囊膜就能抑制经囊膜蛋白吸附细胞表面受体而入侵的病毒[93]。尽管糖蛋白或糖脂可作为哺乳动物病毒受体, 但不同的表面分子结构会导致病毒对物种或组织的取向不同[94]。研究揭示蛙病毒RGV和ADRV能以不同细胞表面的硫酸乙酰肝素作为受体, 经此跨种入侵[95]。蛙病毒成熟和囊膜形成也可发生在不同细胞的囊泡中[31,96,97]。这些研究为蛙病毒跨种感染提供了新注释。已知病毒能用miRNA操纵宿主细胞和病毒基因的表达[98], 借助miRNAs干扰与病毒重组等进行分析, 结果显示敲除病毒膜蛋白基因RGV-2L和RGV-53R能显著抑制病毒装配[42,99]。这表明蛙病毒囊膜蛋白不仅是其吸附入侵的要素, 且能显著影响病毒装配与成熟。分别对大鲵正常血清和感染蛙病毒血清及正常黏液和感染蛙病毒黏液的蛋白图谱进行测试比较, 显示不同程度发生变化[100], 预示蛙病毒感染可引起宿主机体的生理生化反应。蛙病毒RGV和ADRV的基因有99%同源性, 将其分别感染养殖大鲵,构建15个转录组文库, 并进行测序, 结果从8.2亿个有效读数中获得12.8万个注释基因; 在蛙病毒感染自然宿主或跨种感染过程中具有不同的基因表达模式, 所引起宿主应答也各有不同。在跨种感染时,蛙病毒进入宿主后, 迅速表达自身基因、快速复制,但宿主应答较弱, 以此提升其适应性进化及在种间传播的时效性[101]。

以蛙病毒囊膜蛋白基因ADRV-2L和ADRV-58L分别构建重组质粒pcDNA-2L和pcDNA-58L, 并就其对大鲵的免疫保护作用进行评价。对经pcDNA-2L免疫过的大鲵进行蛙病毒ADRV攻毒,其I型干扰素(IFN-1)、抗病毒蛋白(Mx)、主要组织相容性复合物(MHC-IA)和免疫球蛋白M (IgM)表达水平都能明显上调, 存活率为 66.7%, 显著高于用pcDNA-58L免疫的大鲵存活率(3.3%)[78], 经比较可筛出候选疫苗。蛙病毒会采取拮抗或免疫逃逸策略[102,103], 或有效变异, 增强对新物种宿主的适应性, 以突破物种屏障感染新物种[104—106]。

1.2 鲫疱疹病毒(Crucian carp herpesvirus, CaHV)

疱疹病毒目(Herpesvirales)成员是有囊膜、基因组大小为125—290kb的大DNA病毒,在二十面体核衣壳外有层蛋白质基质被膜, 再被囊膜包裹[107]。鱼蛙疱疹病毒科(Alloherpesviridae)以鱼类和两栖类为宿主[108],分为蛙疱疹病毒属(Batrachovirus)、鲤疱疹病毒属(Cyprinivirus)、鮰疱疹病毒属(Ictalurivirus)和鲑疱疹病毒属(Salmonivirus)[6,109,110]。2016年从急性鳃出血症的鲫中分离鲫疱疹病毒CaHV[111](图 2), 基因组为275 kb的线性双链DNA(KU199244)[112], 推测可编码150个基因, 是基因组架构及引发病症与已知鲤疱疹病毒都不同的新毒株[23]。

CaHV的G蛋白偶联受体G蛋白偶联受体(G Protein-Coupled Receptors, GPCR)是一类有七个跨膜结构域的膜蛋白受体, 可作为信号通路或参与信号转导, 并可利用激活细胞内信号通路为病毒的复制提供保障[113]。鲫疱疹病毒G蛋白偶联受体CaHV-25L(或称CaHV-GPCR), 其C端含赖氨酸残基、蛋白激酶C磷酸化位点及豆蔻酰化位点。经截短、缺失或替换等方式, 构建了CaHV-GPCR的C端系列突变子, 并在鱼类细胞中表达。结果证实其C端不同氨基酸对蛋白亚细胞定位与分布状态有不同影响[114]。

鲫疱疹病毒膜蛋白及其靶向分子有研究表明疱疹病毒膜蛋白呈动态分布且有不同作用[115]。CaHV-138L是有两个跨膜结构域的鲫疱疹病毒膜蛋白, 分析显示全长CaHV-138L呈点状分布于质膜或核膜周围, 且与线粒体共定位。当截短其单一或双跨膜结构域时, 就会改变其亚细胞定位, 使之在胞质和胞核中呈斑块状分布。经酵母双杂交和免疫共沉淀筛查到能与该病毒蛋白相互作用的宿主线粒体蛋白FoF1-ATP酶, 并证实CaHV-138L能靶向线粒体蛋白FoF1-ATP酶[116]。这预示该蛋白可通过介导线粒体ATP合成, 为病毒复制提供能量。另外, 对CaHV与CyHV-2高度同源、且含RNase E/G家族典型结构域的蛋白CaHV-31R进行分析, 结果表明它能与内质网和高尔基体等有单层膜结构的细胞器共定位, 可能涉及病毒胞内运输与释放[117]。

图2 鲫疱疹病毒CaHV引起的高致死系统性出血症及感染鲫头肾超薄切片的电镜图 (方进 图)Fig. 2 Crucian carp herpesvirus (CaHV) caused disease with highlylethal systemic hemorrhagic symptoms and electron electronmicrograph of the infected Carassius auratus head kidney ultrathin section. Bar=200 nm

鲫疱疹病毒病防控对鲫疱疹病毒CaHV攻毒和感染的不同品系异育银鲫转录组进行分析, 测试其对病毒的抗性。结果, 三个雌核发育异育银鲫品系对鲫疱疹病毒分别显示出高(H)、中(F)和低(A+)抗性。又从不同品系中鉴定显著差异表达的基因、免疫相关途径及干扰素系统基因等[118]。在H、F和A+品系中, 依次有26条、7条和15条途径与感染或免疫相关基因。鉴定出与病毒载量呈正相关或负相关的表达模块[119]。这不仅显示H品系的免疫力更强, 且为分子标记辅助选择育种及鲫抗病毒分子育种实践提供了新思路。还从被CaHV感染的异育银鲫中, 鉴定出28个含不同免疫球蛋白结构域的蛋白会上调表达; 而且鲫蛋白DICPs能通过激活脂质A驱动荧光素酶, 与肉瘤病毒Src基因同源结构域1蛋白酪氨酸磷酸酶(src-homology 1 protein tyrosine phosphatase, SHP-1)及SHP-2相互作用, 从而抑制干扰素及干扰素刺激基因(Interferon-stimulated genes, ISGs)表达[120]。所鉴定的干扰素系统基因有RIG-Is、LGP2s、IRF1-B、IRF3s、IRF7s、IRF9-B、Mxs及干扰素刺激因子Viperins等。进一步研究显示, CaHV侵染会启动干扰素调节因子RIG-I、遗传学和生理学实验室蛋白2 (Laboratory of genetics and physiology 2, LGP2)表达, 并激活线粒体抗病毒信号通路, 诱导表达干扰素调节因子[121]。从中等抗性的F品系中, 鉴定两个大小不同的3′UTRs干扰素基因, 证实3′UTR参与干扰素基因的转录和翻译, 是调节抗病毒免疫的潜在因素[122]。

通过替代药物来控制水产病害越来越受到关注, 如有益微生物(益生菌probiotics)就被认为是抗生素的有效且生态友好替代品[123,124]。经对未喂饵益生菌而直接用CaHV攻毒的鲫, 与已喂饵益生菌后再攻毒的鲫, 分别测试其成活率和免疫相关基因。结果表明: 喂饵益生菌使鲫抗病毒的应答水平及群体存活率显著提高[125], 该研究为鱼类抗病毒病添加了候选方案。

1.3 克氏螯虾线头病毒(Procambarus clarkia nimavirus, PCV)

克氏螯虾(Procambarus clarkia)也称小龙虾。中国已成为世界养殖小龙虾的最大生产国[126], 其需求和产量仍在增长, 但小龙虾病毒病种类及其危害也随之增加[127—131]。线头病毒是有双层囊膜、基因组大小 280—309 kb、一端带尾、囊膜大小约430 nm×120 nm 的大DNA病毒。曾有小龙虾受线头病毒科(Nimaviridae)成员白班综合症病毒(White spot syndrome virus, WSSV)感染, 并出现白斑症状的报道[132,133]。或将小龙虾作为WSSV的实验动物[134], 感染后也能观察到白斑症状。但从自然感染小龙虾中分离鉴定线头病毒的文献仍很少见。下面简介相关研究。

PCV的核酸检测与超微形态某养殖场虾群突然大量死亡却无体表病症, 采集幸存小龙虾样本, 并对这些无典型白斑症的虾解剖观察。肠道无食物, 但因出血(或充血)而呈淡蓝色, 肝胰腺呈淡黄或白色, 部分虾鳃发黑。以幸存小龙虾核酸作为模板, 设计小龙虾线头病毒PCV特有基因PCV-87R及五种对虾病毒(WSSV、IHHNV、TSV、YHV及MrNV)保守基因的引物[135—137], 进行PCR或RTPCR检测。结果检出PCV-87R与wssv-vp28为阳性,其他均呈阴性。这预示PCV是一株新线头病毒, 与已知白斑病毒成员之间存在关键基因的遗传与变异。

对自然感染无病症小龙虾组织制备的超薄切进行电镜观察, 可见病毒颗粒存在于不同组织和细胞中。如在鳃和肠细胞中, 有大量病毒分布在胞质和核质中, 或规则排列在核膜周围, 并伴随广泛的组织病变。完整PCV颗粒大小约300 nm×110 nm、两端钝圆呈短杆状。负染电镜图显示: PCV核衣壳呈有节杆状[109](图 3)。

图3 小龙虾线头病毒PCV无症状感染的小龙虾及病毒核衣壳负染电镜图 (李涛 图)Fig. 3 Procambarus clarkia nimavirus (PCV) infected red swamp crayfish were asymptomatic and the negative staining electron micrograph of the viral nucleocapsid. Bar=200 nm

PCV基因组架构及其多变区PCV基因组DNA大小为287 kb (MH663976), 推定可编码180个基因。有观点认为可将对虾白斑综合征病毒基因大片段缺失作为时空进化的标记[138]。将PCV基因组与已知对虾白斑综合征病毒基因组进行比较, 显示PCV在易重组、有进化意义的核酸片段相应位置[139]也有缺失。此外, PCV另有一个差异显著的核酸片段及普遍存在的核酸插入、缺失、替换及基因突变。

1.4 淡水蓝藻菌噬藻体及水生大DNA病毒新成员

病毒历史远比人类史悠远, 而且数量极大, 地球被称为 “病毒星球” (A Planet of Viruses)[140]。地球上的病毒已超过宇宙中繁星的数量, 若将预测地球上的1031个病毒首尾相连, 其长度将达1亿光年[141]。肌尾噬藻体(Cyanophage)是感染原核蓝藻菌的病毒, 属有尾目(Caudovirales)中肌尾噬藻体科(Myoviridae)的成员, 病毒颗粒由头部和尾部两部分组成, 呈蜊蚪形, 其DNA基因组大小约120 kb[142]。噬藻体可感染蓝藻甚至操控水华蓝藻的种群密度, 并将宿主机体和细胞转化为有机物, 从而驱动地球物理化学循环; 在介导微生物之间的基因水平转移、维持水生微生物群落多样性等方面也发挥重要作用[143—147]。水体中有许多感染真核藻的大DNA病毒, 如藻DNA病毒(Phycodnavirus), 属于藻类DNA病毒科(Phycodnaviridae), 通常为二十面体, 其DNA基因组的分子量为160—380 kb。还有感染原生动物变形虫的巨病毒(Giant virus), 其基因组大小甚至可达500 kb, 被认为是规模迅速扩张的水生大DNA病毒家族新成员[148]。相关新认知拓展了水生大DNA病毒的范畴, 挑战了对病毒的传统认识[149], 日渐模糊了病毒与细胞间的界限[150]。

噬藻体感染蓝藻菌不仅改变宿主种群密度, 也促进噬藻体的适应性及与宿主的共同进化[151]。噬藻体修饰宿主细胞膜能增强光保护及病毒编码光合蛋白的表达, 产生新的代谢通路或网络[61]。水体中病毒对宿主的致死率很高, 同时, 包括蓝藻菌在内的水生细菌对病毒的抵抗力也在增强[152]。噬藻体感染通常取决宿主的防御效果[153], 并由此可获得高突变率及重组率[154]。由于从基因组数据所获微生物的功能信息及其可信度都有限。因此, 纯培养仍是微生物利用的前提与基础[155]。运用无菌技术, 经优化条件、反复筛选、纯化鉴定、培养和保藏等过程, 才可获得很少量噬藻体纯培养物[156]。自然界中不可培养微生物(Viable but non-culturable, VBNC)仍占绝大多数[157], 导致对微生物活体总数的低估[158], 也突显基础微生物研究的难点及蕴藏开发微生物资源的潜能[159]。

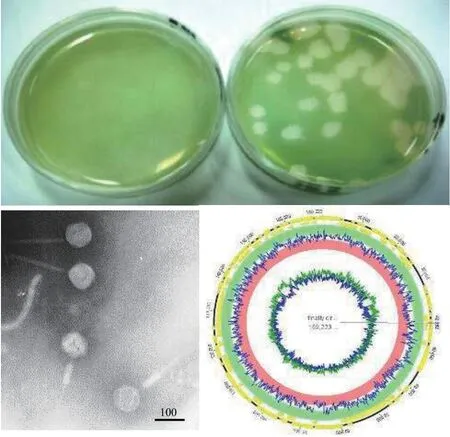

铜绿微囊藻肌尾噬藻体-滇池株(Microcystis aeruginosa myovirus in Lake Dianchi, MaMV-DC)的分离及超微形态铜绿微囊藻肌尾噬藻体-滇池株MaMV-DC是利用微囊藻、鱼腥藻、聚球藻等21株蓝藻菌, 对昆明滇池采集的水样进行筛查, 并经噬藻体单斑分离、扩大培养及纯化所获得的噬藻体。其宿主范围窄, 仅感染铜绿微囊藻株Microcystic aeruginosaFACHB-524, 噬藻斑为圆形透亮空斑; 噬藻体呈蝌蚪形, 二十面体头部直径约70 nm,收缩尾长约160 nm (图 4)。MaMV-DC的裂解量约为80个感染活性单位[160]。此外, 还有些噬藻体有形态独特的噬斑, 如噬藻体A-4L可形成同心圆噬斑, 而同心圆形成与光照节律有关[161]。

图4 铜绿微囊藻肌尾噬藻体-滇池株MaMV-DC的噬斑、负染电镜图及基因组图谱 (欧铜 图)Fig. 4 The plaque, negative staining electron micrograph and genome map of Microcystis aeruginosa myovirus in Lake Dianchi(MaMV-DC). Bar=100 nm

MaMV-DC基因组的结构测序分析显示MaMV-DC基因组(KF356199)为末端循环冗余、双链线性DNA大小169 kb, 推测可编码170个基因, 其中含一个转运RNA (tRNA)基因。MaMV-DC与日本报道的铜绿微囊藻噬藻体Ma-LMM01(AB231700)基因组序列相似性为86%, 有150个同源基因[162]; 而与宿主铜绿微囊藻有29个同源基因。当用主要衣壳蛋白构建进化树时, MaMV-DC与Ma-LMM01聚在一簇, 但两者所携带的宿主或其他物种核酸片段却差异显著[163]。另外, 短尾噬藻体A-4L, 基因组DNA大小约为42 kb, 推测可编码38个基因[164], 不属大DNA病毒类群, 但能感染模式生物鱼腥藻Anabaenasp. PCC 7120, 可作为载体, 用于研究噬藻体基因功能。

噬藻体功能基因噬藻体的生态功能是要凭借与宿主相互作用而体现[165]。对肌尾噬藻蛋白A-1(L)-ORF36功能进行了鉴定, 显示这是一个能与细胞表面脂多糖(LPS) O抗原结合的蛋白。还证实噬藻体正是利用该蛋白与细胞表面脂多糖特异性吸附而入侵蓝藻菌的[166]。从丝状蓝藻噬藻体(Planktothrix agardhiivirus isolated from Lake Donghu,PaV-LD, NC_016564) 中鉴定藻胆体降解蛋白基因(NblA)、穿孔素基因和内肽酶基因等[167,168]。铜绿微囊藻噬藻体基因MaMV-DC-5L也是编码藻胆体降解蛋白基因, 能在模式集胞藻Synechocystissp.PCC 6803中表达, 显著消减宿主藻蓝蛋白吸收峰,促进噬藻体释放[163]。已鉴定的噬藻体基因还有不同光合作用蛋白基因[169]和能量与代谢相关基因[170]。

噬藻体与宿主的相互作用微生物基因组所含规律间隔短回文重复序列及相关系统(Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated endonuclease, CRISPR-Cas), 因为它能与crRNA(CRISPR-derived RNA)碱基配对、识别并使入侵的噬菌体及其他病原体被Cas蛋白切割降解, 而被证明是细菌等原核生物的防御系统[171,172]。鉴定了功能多样化、且有不同切割效率的V型CRISPRCas系统及由RNA引导的效应蛋白Cas12[173]。还鉴定了丝状蓝藻菌长尾噬菌体vB_AphaS-CL131编码的V-U2 CRISPR-Cas系统[174], 显示在蓝藻菌中普遍存在V-U2的效应蛋白[175]。而噬菌体也进化出不同抗-CRISPR的蛋白(Acr), 能抑制或逃逸宿主CRISPR-Cas的防御作用[176]。将铜绿微囊藻肌尾噬藻体-滇池株MaMV-DC置于低温冰箱(-80℃)中保存超过3年, 不仅保留对Microcystis aeruginosaFACHB-524的感染性, 也能感染微囊藻Microcystis flosaquaeTF09、Microcystis aeruginosaTA09和Microcystis wesenbergiiDW09, 但敏感性不同。再对不同微囊藻株的防御系统CRISPR-Cas进行分析比较,显示其分子结构与含量都有变化。这证明CRISPR-Cas会影响微囊藻对噬藻体的敏感性, 或能决定噬藻体的宿主范围[177]。CRISPR-Cas已作为基因编辑工具广泛应用[178], 并取得相应成果, 将噬菌体酶靶向嵌入细菌特定基因位点, 则能破坏细菌生物膜;而利用噬菌体将抗生素敏感基因导入耐药菌中, 则可使耐药菌致敏[179], 由此能获得抗病毒新对策[180]。

2 机遇与挑战

我国渔业已进入设施化、智能化与生态化的历史变革时期[181], 对水产健康生态养殖有更高要求, 也给水生病毒学学科发展带来难得契机。水生大DNA病毒的性质特征、遗传进化及与宿主及水生态关联的研究基础相对薄弱, 对水产动物病毒病预测预警、智能健康水产养殖体系构建、大DNA病毒群落多样性及其水生态阈值评估的认知也参差不齐, 正面临前所未有的挑战[182]。

2.1 先进技术是提升水生大DNA病毒研究水平的载体

构建和运用大数据网络, 宏观与微观结合开展研究是水生大DNA病毒学新的生长点。多国学者合作, 已从全球不同水体采集样品重建大DNA病毒基因组信息, 围绕其地理分布、基因多样性、代谢特征等开展研究。阐明水体大DNA病毒全球分布的模式, 使其系统发育多样性及功能多样性数据各提升11倍和10倍; 发现病毒基因组编码与光合作用及底物运输过程相关蛋白; 揭示大DNA病毒普遍具备使宿主重编程的功能[148]。单病毒颗粒示踪、基因组解析、转录组分析也运用于水生大DNA病毒研究中[101,183]; 剖析鉴定与疾病相关的DNA序列[184],可极大提高对疾病发生机制及病毒与水环境相关性的认识, 并推动水产动物病毒病由随机检测向系统防控战略布局转变。也由此可见, 掌握和运用关键核心技术将为拓展水生病毒学学科注入鲜活动力, 而新技术突破与经典技术融合集成则会加速科研成果向实际应用转化。

2.2 整合、集成水生病毒学知识体系

淡水水生大DNA病毒研究是水生病毒学学科的重要内容及原有基础。随着对水产品需求的不断增长及水产养殖规模持续扩大, 水产动物疾病也如影随形。因此, 应使水生病毒学知识从零星分散向交汇集成转化, 尤其要强化水生病毒分类、溯源与遗传进化研究。

分类完全开放、不断更新发布的《病毒分类报告》(http://ictv.global/report/), 是由国际病毒分类与命名的权威机构——国际病毒分类委员会(The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, ICTV), 按病毒性质、亲缘关系进行归类编排,为学者与公众随时了解新病毒的共性与特征而提供的纲要。随着对更多水生大DNA病毒新成员及其与宿主相互作用、协同进化轨迹的认知[185], 将会使大DNA病毒的知识更加丰富和立体。

溯源寻觅病毒传播源头有益摸清病毒初始发生过程与传播途径, 预测病毒病流行趋势与潜在风险, 为疫病防控提供科学依据。但病毒只能在活细胞中复制, 没留下化石, 其起源很难追踪, 须从宿主或其他物种演化史中找答案。部分大DNA病毒有共同的祖先和起源[186], 或源自不同水生生物群落[187,188]; 有些大DNA病毒除了编码复制和结构形成所必需的蛋白质核心基因外, 还会伴随基因丢失或募集其他物种基因而形成新病毒[189]。但许多病毒的起源尚不清楚, 尤其是一些新发病毒病原。因此, 应强化对水生大DNA病毒的溯源研究。

进化转换、插入、缺失、颠换、重组、重配及自然选择等基因突变方式是病毒进化与多样性的源泉。病毒复制频率高, 发生变异也较其他生物要快。病毒除了具备遗传可变性, 还能通过跨宿主感染, 高效扩大病毒的多样性。有观点认为,病毒在地球生命的进化中扮演重要的角色, 可导致重大进化飞跃[190], 甚至还存在与宿主互惠共生病毒(Mutualistic viruses)。

2.3 鱼水共护, 促生态健康渔业发展

水生大DNA病毒病的流行方式与病毒、水生生物及水环境存在耦合关系[191]。病毒导致水产动物病毒病流行, 或是噬藻体不作为任由水华暴发都会影响水生态健康及人与自然和谐共处[192]。以鱼护水、以水养鱼, 只有鱼水共养护的健康生态渔业才可持续发展和有更旺盛的生命力。因此, 可利用分子生物学检测方法和模型构建预警网络等途径, 对机体及水生动物健康状况进行评估[193]。但试图通过投放药物, 来防控水产动物疾病的可操作性仍然很低[194,195]。总之, 面向绿色水产的全球重大需求, 要实现产品优质、环境优美、生态优稳、养鱼护水的渔业健康、可持续发展愿景(https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1654687744824397971&wfr=spider&for=pc), 就要拓展水生病毒学新方法、新技术与新知识的储备; 探索水生大DNA病毒的感染、复制、发病机制、细胞/宿主取向, 及病毒、宿主与水环境相互作用等基础理论问题; 深入研究水生动物病毒病因、流行方式、预警阈值及防控管理等实践中的新问题, 寻求噬藻体调控水环境核心技术的突破。研究者不断探寻防御病毒新策略,为水生动物提供更先进的卫生服务, 以保障水产动物健康, 创建鱼水共护新机制。

参考文献:,

[1]Cressey D. Aquaculture: Future fish [J].Nature, 2009,458(7237): 398-400.

[2]Godfray H C, Beddington J R, Crute I R,et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people [J].Science, 2010, 327(5967): 812-818.

[3]Gui J F, Tang Q S, Li Z J,et al. Aquaculture in China:Success Stories and Modern Trends [M]. Wiley Blackwell, 2018: 1-711.

[4]Fisheries and Fisheries Administration Bureau of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. National Fisheries Technology Extension Station, China Fisheries Association. Report on the health Status of Aquatic Animals in China [M]. Beijing: China Agriculture Press,2019: 1-106. [农业农村部渔业渔政管理局, 全国水产技术推广总站, 中国水产学会, 2019 中国水生动物卫生状况报告 [M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2019: 1-106.]

[5]Stentiford G D, Neil D M, Peeler E J,et al. Disease will limit future food supply from the global crustacean fishery and aquaculture sectors [J].Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2012, 110(2): 141-157.

[6]Zhang Q Y, Gui J F. Virus genomes and virus-host interactions in aquaculture animals [J].Science China Life Sciences, 2015, 58(2): 156-169.

[7]Abdelrahman H, ElHady M, Alcivar-Warren A,et al.Aquaculture genomics, genetics and breeding in the United States: current status, challenges, and priorities for future research [J].BMC Genomics, 2017, 18(1):191.

[8]Gui J F, Zhu Z Y. Molecular basis and genetic improve-ment of economically important traits in aquaculture animals [J].Chinese Science Bulletin, 2012, 57(15): 1751-1760. [桂建芳, 朱作言. 水产动物重要经济性状的分子基础及其遗传改良 [J]. 科学通报, 2012, 57(15): 1751-1760.]

[9]Gui J F. Fish biology and biotechnology is the source for sustainable aquaculture [J].Science China Life Sciences,2014, 44(12): 1195-1197. [桂建芳. 鱼类生物学和生物技术是水产养殖可持续发展的源泉 [J]. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2014, 44(12): 1195-1197.]

[10]Naylor R L, Goldburg R J, Primavera J H,et al. Effect of aquaculture on world fish supplies [J].Nature, 2000,405(6790): 1017-1024.

[11]Smith M D, Roheim C A, Crowder L B,et al. Sustainability and global seafood [J].Science, 2010, 327(5967):784-786.

[12]Raoult D, Forterre P. Redefining viruses: lessons from Mimivirus [J].Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2008,6(4): 315-319.

[13]Jancovich J K, Qin Q, Zhang Q Y,et al. Ranavirus Teplication: Molecular, Cellular, and Immunological Events[M]//Gray M J, Chinchar V G (Eds.), Ranaviruses Lethal Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates. New York:Springer, 2015: 105-139.

[14]WikiMili, Nucleocytoplasmic large DNA viruses.https://wikimili.com/en/Nucleocytoplasmic_large_DNA_viruses, 2020.

[15]Colson P, La Scola B, Levasseur A,et al. Mimivirus:leading the way in the discovery of giant viruses of amoebae [J].Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2017, 15(4):243-254.

[16]Koonin E V, Yutin N. Evolution of the large nucleocytoplasmic DNA viruses of eukaryotes and convergent origins of viral gigantism [J].Advances in Virus Research,2019(103): 167-202.

[17]Adriaenssens E M, Krupovic M, Knezevic P,et al. Taxonomy of prokaryotic viruses: 2016 update from the ICTV bacterial and archaeal viruses subcommittee [J].Archives of Virology, 2017, 162(4): 1153-1157.

[18]Monier A, Claverie J M, Ogata H. Taxonomic distribution of large DNA viruses in the sea [J].Genome Biology, 2008, 9(7): R106.

[19]Short S M, Short C M. Diversity of algal viruses in various North American freshwater environments [J].Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 2008, 51(1): 13-21.

[20]Elde N C, Child S J, Eickbush M T,et al. Poxviruses deploy genomic accordions to adapt rapidly against host antiviral defenses [J].Cell, 2012, 150(4): 831-884.

[21]Zhang Q Y, Gui J F. Diversity, evolutionary contribution and ecological roles of aquatic viruses [J].Science China Life Sciences, 2018, 61(12): 1486-1502.

[22]Chinchar V G, Hick P, Ince I A,et al. ICTV report consortium. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: iridoviridae [J].Journal of General Virology, 2017, 98(5): 890-891.

[23]Gui L, Zhang Q Y. Disease Prevention and Control[M]//Gui J F, Tang Q S, Li Z J,et al. Aquaculture in China: Success Stories and Modern Trends. Chichester:Wiley-Blackwell, 2018: 577-598.

[24]Zhang Q Y. Advances in studies on biodiversity of cyanophages [J].Microbiology China, 2014, 41(3): 545-559.[张奇亚. 噬藻体生物多样性的研究动态 [J]. 微生物学通报, 2014, 41(3): 545-559.]

[25]Schulz F, Yutin N, Ivanova N N,et al. Giant viruses with an expanded complement of translation system components [J].Science, 2017, 356(6333): 82-85.

[26]Abrahão J, Silva L, Silva L S,et al. Tailed giant Tupanvirus possesses the most complete translational apparatus of the known virosphere [J].Nature Communications, 2018, 9(749): 1-12.

[27]China Pictorial, April Issue 1955. Prevention and Treatment of Fish Diseases [A]. [人民画报1955年4月号. 防治鱼病] http://www.ihb.cas.cn/sq90/History/sq_lssj/202006/t20200609_5603618.html.

[28]Rao Q Z. An effective ways to prevent microsystis blooms in fishpond [J].Scientific Bulletin, 1952(Z1): 1-3. [饶钦止, 介绍一个消灭“湖靛”的有效方法 [J]. 科学通报, 1952(Z1): 1-3.]

[29]Section of Virus Study, Third Laboratory, Institute of Hydrobiology, Academia Sinica. Studies on the causative agent of hemorrhage of the grass carp (Ctenopharyn-godon idellus) [J].Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica,1978, 2(3): 321-330. [中国科学院水生生物研究所第三室病毒组. 草鱼出血病病原的研究 [J]. 水生生物学集刊, 1978, 2(3): 321-330.]

[30]Zhang Q Y, Li Z Q, Jiang Y L,et al. Preliminary studies on virus isolation and cell infection from diseased frogRnan grylio[J].Acta Hydrobiology Sinica, 1996, 20(4):390-392. [张奇亚, 李正秋, 江育林, 等. 沼泽绿牛蛙病毒的分离及其细胞感染的研究 [J]. 水生生物学报,1996, 20(4): 390-392.]

[31]Zhang Q Y, Li Z Q, Gui J F. Studies on morphogenesis and cellular interactions ofRana gryliovirus in an infected fish cell line [J].Aquaculture, 1999, 175(3-4): 185-197.

[32]Zhang Q Y, Xiao F, Xie J,et al. Complete genome sequence of lymphocystis disease virus (LCDV-C) isolated from China [J].Journal of Virology, 2004, 78(13):6982-6994.

[33]Lei X Y, Ou T, Zhu R L,et al. Sequencing and analysis of the complete genome ofRana gryliovirus (RGV) [J].Archives of Virology, 2012(157): 1559-1564.

[34]Chen Z Y, Gui J F, Gao X C,et al. Genome architecture changes and major gene variations ofAndrias davidianusranavirus (ADRV) [J].Veterinary Research, 2013(44):101.

[35]Xie J, Li Z Q, Zhang Q Y,et al. Detection ofRana gryliovirus (RGV) in host frog tissues by using immunohistochemisrey assay [J].Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica,2002, 26(5): 438-443. [谢简, 李正秋, 张奇亚, 等. 免疫组化法检测美国青蛙组织中的蛙虹彩病毒 [J]. 水生生物学报, 2002, 26(5): 438-443.]

[36]Zhang Q Y, Zhao Z, Xiao F,et al. Molecular characterization of threeRana gryliovirus (RGV) isolates andParalichthys olivaceuslymphocystis disease virus(LCDV-C) in iridoviruses [J].Aquaculture, 2006,251(1): 1-10.

[37]Sun W, Huang Y H, Zhao Z,et al. Characterization of theRana gryliovirus 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and its novel role in suppressing virus-induced cytopathic effect [J].Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2006, 351(1): 44-50.

[38]Zhao Z, Shi Y, Ke F,et al. Constitutive expression of thymidylate synthase from LCDV-C induces foci formation and anchorage-independent growth in fish cells [J].Virology, 2008, 372(1): 118-126.

[39]Zhao Z, Ke F, Huang Y H,et al. Identification and characterization of a novel envelope protein inRana gryliovirus [J].Journal General Virology, 2008(89): 1866-1872.

[40]Zhao Z, Ke F, Shi Y,et al.Rana gryliovirus thymidine kinase gene: an early gene of iridovirus encoding for the cytoplasmic protein [J].Virus Genes, 2009(38): 345-352.

[41]Ke F, Zhao Z, Zhang QY. Cloning, expression and subcellular distribution of aRana gryliovirus late gene encoding ERV1 homologue [J].Molecular Biology Reports, 2009(36): 1651-1659.

[42]He L B, Ke F, Wang J,et al.Rana gryliovirus (RGV)envelope protein 2L: subcellular localization and essential roles in virus infectivity revealed by conditional lethal mutant [J].Journal of General Virology, 2014(95): 679-690.

[43]Gui L, Chinchar V G, Zhang Q Y. Molecular basis of pathogenesis of emerging viruses infecting aquatic animals [J].Aquaculture and Fisheries, 2018(3): 1-5.

[44]Zhang Q Y, Gui J F. Aquatic Virology [M]. Beijing:Higher Education Press, 2008: 1-414. [张奇亚, 桂建芳.水生病毒学 [M]. 北京: 中国高等教育出版社, 2008: 1-414.]

[45]Zhang Q Y, Gui J F. Atlas of Aquatic Viruses and Viral Diseases [M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2012: 1-479. [张奇亚, 桂建芳. 水生病毒及病毒病图鉴 [M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2012: 1-479.]

[46]Gray M J, Chinchar V G. Ranaviruses Lethal Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates [M]. New York: Springer,2015: 1-246.

[47]Deng M, He J G, Zuo T,et al. Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV) from Siniperca chuatsi: Development of a PCR detection method and the new evidence of iridovirus [J].Chinese Journal of Virology,2000, 16(4): 365-369. [邓敏, 何建国, 左涛, 等. 鳜鱼传染性脾肾坏死病毒 (ISKNV)PCR检测方法的建立及虹彩病毒新证据 [J]. 病毒学报, 2000, 16(4): 365-369.]

[48]Ao J, Chen X W. Identification and characterization of a novel gene encoding an RGD-containing protein in large yellow croaker iridovirus [J].Virology, 2006, 355(2):213-222.

[49]Shi C Y, Jia K T, Yang B,et al. Complete genome sequence of a Megalocytivirus (familyIridoviridae) associated with turbot mortality in China [J].Virology Journal, 2010(7): 159.

[50]Song W J, Qin Q W, Qiu J,et al. Functional genomics analysis of Singapore grouper iridovirus: complete sequence determination and proteomic analysis [J].Journal of Virology, 2004, 78(22): 12576-12590.

[51]https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_online_report/dsdna-viruses/w/iridoviridae#Citation.

[52]Chinchar V G, Waltzek T B, Subramaniam K. Ranaviruses and other members of the familyIridoviridae:Their place in the virosphere [J].Virology, 2017(511):259-271.

[53]Boyer M, Yutin N, Pagnier I,et al. Giant Marseillevirus highlights the role of amoebae as a melting pot in emergence of chimeric microorganisms [J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of The United States of America, 2009, 106(51): 21848-21853.

[54]McNeill W H. Plagues and Peoples [M]. Garden City, N Y, Anchor Press/Doubleday, 1976: 1-369.

[55]Grubaugh N D, Ladner J T, Lemey P,et al. Tracking virus outbreaks in the twenty-first century [J].Nature, 2019,4(1): 10-19.

[56]Lassen K. Virus-Host Interactions [J].Cell, 2011,146(2): 183-185.

[57]Rothenburg S, Brennan G. Species-specific host-virus interactions: implications for viral host range and virulence [J].Trends in Microbiology, 2020, 28(1): 46-56.

[58]World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE). Benefits of aquatic animals are infinite [C]. https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Media_Center/docs/pdf/PortalAqua-ticAnimals/EN_Brochure%20Aquatic%20Animals_FINAL_LD.pdf, 2019.

[59]Cavalli L S, Brito K C T, Brito B G. One health, one aquaculture: aquaculture under one health umbrella [J].Journal of Marine Biology and Aquaculture, 2015, 1(1):1-2.

[60]Wilson W H, Van Etten JL. Allen M J ThePhycodnaviridae: the story of how tiny giants rule the world [J].Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology,2009(328): 1-42.

[61]Roitman S, Hornung E, Flores-Uribe J,et al. Cyanophage-encoded lipid desaturases: oceanic distribution,diversity and function [J].The ISME Journal, 2018(12):343-355.

[62]Chinchar V G, Waltzek T B. Ranaviruses: not just for frogs [J].PLoS Pathogens, 2014, 10(1): e1003850.

[63]Li W, Zhang X, Weng S,et al. Virion-associated viral proteins of a Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) iridovirus (genusRanavirus) and functional study of the major capsid protein (MCP) [J].Veterinary Microbiology, 2014, 172(1-2): 129-139.

[64]Wang N, Zhang M, Zhang L,et al. Complete genome sequence of a ranavirus isolated from Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) [J].Genome Announcements, 2014, 2(1): e1032-e1113.

[65]Stohr A C, Lopez-Bueno A, Blahak S,et al. Phylogeny and differentiation of reptilian and amphibian ranaviruses detected in Europe [J].PLoS One, 2015(10):e118633.

[66]Wirth W, Schwarzkopf L, Skerratt L F,et al. Ranaviruses and reptiles [J].Peer J, 2018(6): e6083.

[67]Garner T W, Stephen I, Wombwell E,et al. The amphibian trade: bans or best practice [J].Ecohealth, 2009(6): 148-151.

[68]Fryer J L, Lannan C N. Three decades of fish cell culture: A current listing of cell lines derived from fishes[J].Journal of Tissue Culture Methods, 1994(16): 87-94.

[69]Lakra W S, Swaminathan, T R, Joy K P. Development,characterization, conservation and storage of fish cell lines: A review [J].Fish Physiology and Biochemistry,2011, 37(1): 1-20.

[70]Pandey G. Overview of fish cell lines and their uses [J].International Journal of Engineering Research and Applications, 2013, 2(3): 580-590.

[71]Sinzelle L, Thuret R, Hwang H Y,et al. Characterization of a novelXenopus tropicaliscell line as a model forin vitrostudies [J].Genesis, 2012(50): 316-324.

[72]Bertin A, Hanna P, Otarola G,et al. Cellular and molecular characterization of a novel primary osteoblast culture from the vertebrate model organismXenopus tropicalis[J].Histochemistry and Cell Biology, 2015,143(4): 431-442.

[73]Mollard R. Culture, cryobanking and passaging of karyotypically validated native Australian amphibian cells[J].Cryobiology, 2018(81): 201-205.

[74]Yuan J D, Chen Z Y, Huang X,et al. Establishment of three cell lines from Chinese giant salamander and their sensitivities to the wild-type and recombinant ranavirus[J].Veterinary Research, 2015, 46(1): 58.

[75]Lei C K, Chen Z Y, Zhang Q Y. Comparative susceptibility of three aquatic animal cell lines to two ranaviruses[J].Journal of Fisheries of China, 2016, 40(10): 1643-1647. [雷存科, 陈中元, 张奇亚. 三种水生动物细胞系对两株蛙病毒敏感性的比较 [J]. 水产学报, 2016,40(10): 1643-1647.]

[76]Chen Q, Ma J, Fan Y,et al. Identification of type I IFN in Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus) and the response to an iridovirus infection [J].Molecular Immunology, 2015, 65(2): 350-359.

[77]Robert J, Jancovich J K. Recombinant ranaviruses for studying evolution of hos. t-pathogen interactions in ectothermic [J].Vertebrates Viruses, 2016, 8(7): E187.

[78]Chen Z Y, Li T, Gao X C,et al. Protective immunity induced by DNA vaccination against ranavirus infection in Chinese giant salamanderAndrias davidianus[J].Viruses, 2018, 10(2): 52.

[79]Luo J, Deng Z L, Luo X,et al. A protocol for rapid generation of recombinant adenoviruses using the AdEasy system [J].Nature Protocols, 2007, 2(5): 1236-1247.

[80]Zhao Z, Ke F, Gui J F,et al. Characterization of an early gene encoding for dUTPase fromRana gryliovirus [J].Virus Research, 2007, 123(2): 128-137.

[81]Zhao Z, Zhang Q Y. Structure analysis of thymidylate synthase gene from LCDV-C [J].Virologica Sinica,2004, 19(6): 602-606. [赵哲, 张奇亚. 中国淋巴囊肿病毒胸苷酸合酶基因结构特点及分析 [J]. 中国病毒学,2004, 19(6): 602-606.]

[82]Chen G, Ward B M, Yu K H,et al. Improved knockout methodology reveals that frogvirus 3 mutants lacking either the 18K immediate-early gene or the truncatedvIF-2alpha gene are defective for replication and growthin vivo[J].Journal of Virology, 2011, 85(2): 11131-11138.

[83]He L B, Ke F, Zhang Q Y.Rana gryliovirus as a vector for foreign gene expression in fish cell [J].Virus Research, 2012, 163(1): 66-73.

[84]Huang X, Pei C, He L B,et al. The construction of a novel recombinant virus Δ67R-RGV and analysis of 67R gene function [J].Chinese Journal Virology, 2014,30(5): 495-501. [黄星, 裴超, 何利波, 等. 一株新的重组蛙病毒Δ67R-RGV的构建及基因67R的功能鉴定 [J].病毒学报, 2014, 30(5): 495-501.]

[85]He L B, Gao X C, Ke F,et al. A conditional lethal mutation inRana gryliovirus ORF 53R resulted in a marked reduction in virion formation [J].Virus Research, 2013,177(2): 194-200.

[86]Huang X, Fang J, Chen Z Y,et al.Rana gryliovirus TK and DUT gene locus could be simultaneously used for foreign gene expression [J].Virus Research, 2016,214(2): 33-38.

[87]Plemper R K. Cell entry of enveloped viruses [J].Current Opinion in Virology, 2011, 1(2): 92-100.

[88]Zeng X T, Gao X C, Zhang Q Y.Rana gryliovirus 43R encodes an envelope protein involved in virus entry [J].Virus Genes, 2018, 54(6): 779-791.

[89]Eaton H E, Metcalf J, Penny E,et al. Comparative genomic analysis of the familyIridoviridae: re-annotating and defining the core set of iridovirus genes [J].Virology Journal, 2007(4): 11.

[90]Zeng X T, Zhang Q Y. Interaction between two iridovirus core proteins and their effects on ranavirus (RGV)replication in cells from different species [J].Viruses,2019, 11(5): E416.

[91]Zhang R, Zhang Q Y. Adenosine triphosphatase activity and cell growth promotion ofAndrias davidianusranavirus 96L-encoded protein (ADRV-96L) [J].Microbiology China, 2018, 45(5): 1090-1099. [张锐, 张奇亚.大鲵蛙病毒编码的96L蛋白(ADRV-96L)有ATPase活性和促进细胞生长的作用 [J]. 微生物学通报, 2018,45(5): 1090-1099.]

[92]Ming C Y, Ke F, Zhang Q Y. The Expression and immunogenic analysis of ranaviruses homologous proteins RGV-27R and ADRV-85L [J].Chinese Journal of Virology, 2019, 35(6): 926-934. [明成玥, 柯飞. 张奇亚 蛙病毒同源蛋白ADRV-85L和RGV-27R的表达及其产物免疫原性分析 [J]. 病毒学报, 2019, 35(6): 926-934.]

[93]Kong B, Moon S, Kim Y,et al. Virucidal nano-perforator of viral membrane trapping viral RNAs in the endosome [J].Nature Communications, 2019, 10(1): 185.

[94]Thompson A J, de Vries R P, Paulson J C. Virus recognition of glycan receptors [J].Current Opinion in Virology, 2019(34): 117-129.

[95]Ke F, Wang Z H, Ming C Y,et al. Ranaviruses bind cells from different species through interaction with heparan sulfate [J].Viruses, 2019, 11(7): E593.

[96]Zhang Q Y Xiao F, Li Z Q,et al. Characterization of an iridovirus form the cultured pig frog (Rana grylio) with lethal syndrome [J].Diseases of Aquatic Organisms,2001, 48(1): 27-36.

[97]Liu Y, Tran B, Wang F,et al. Visualization of assembly intermediates and budding vacuoles of Singapore grouper iridovirus in grouper embryonic cells [J].Scientific Reports, 2016(6): 18696.

[98]Skalsky R L, Cullen B R. Viruses, microRNAs, and host interactions [J].Annual Review of Microbiology,2010(64): 123-141.

[99]Kim Y S, Ke F, Lei X Y,et al. Viral envelope protein 53R genehighly specific silencing and iridovirus resistance in fish cells by amiRNA [J].PLoS One, 2010(5):e10308.

[100]Yuan J D, Chen Z Y, Zhang Q Y. Comparative analysis of serum and skin mucus protein profiles between ranavirus-infectud and normal Chinese giant salamanderAndrias davidianus[J].Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica,2016, 40(3): 594-600. [袁江迪, 陈中元, 张奇亚. 正常和蛙病毒感染后大鲵血清和黏液蛋白图谱比较分析 [J].水生生物学报, 2016, 40(3): 594-600.]

[101]Ke F, Gui J F, Chen Z Y,et al. Divergent transcriptomic responses underlying the ranaviruses-amphibian interaction processes on interspecies infection of Chinese giant salamander [J].BMC Genomics, 2018(19): 211.

[102]Ke F, Zhang Q Y. Aquatic animal viruses mediated immune evasion in their host [J].Fish and Shellfish Immunology, 2019(86): 1096-1105.

[103]Jones S, Nelson-Sathi S, Wang Y,et al. Evolutionary,genetic, structural characterization and its functional implications for the influenza A (H1N1) infection outbreak in India from 2009 to 2017 [J].Scientific Reports, 2019,9(1): 14690.

[104]Stöhr A C, Blahak S, Heckers K O,et al. Ranavirus infections associated with skin lesions in lizards [J].Veterinary Research, 2013, 44(1): 1-10.

[105]Woo H J, Reifman J. Quantitative modeling of virus evolutionary dynamics and adaptation in serial passages using empirically inferred fitness landscapes [J].Journal of Virology, 2014, 88(2): 1039.

[106]Sawyer S L, Elde N C. A cross-species view on viruses[J].Current Opinion in Virology, 2012, 2(5): 561-568.

[107]McElwee M, Vijayakrishnan S, Rixon F,et al. Structure of the herpes simplex virus portal-vertex [J].PLoS Biology, 2018, 16(6): e2006191.

[108]Davison A J, Eberle R, Ehlers B,et al. The order Herpesvirales [J].Archives of Virology, 2009, 154(1):171-177.

[109]Gui L, Zhang Q Y. A brief review on aquatic animal virology researches in China [J].Journal of Fisheries of China, 2019, 43(1): 168-187. [桂朗, 张奇亚. 中国水产动物病毒学研究概述 [J]. 水产学报, 2019, 43(1): 168-187.]

[110]Osterrieder K. Chapter 9 Herpesvirales [M]//James N(Eds.), Fenner’s Veterinary Virology (5th eds.), Elsevier Academic Press, 2017: 189-216.

[111]Fang J, Deng Y S, Wang J,et al. Pathological changes of acute viral hemorrhages in the gills of crucian carp [J].Journal of Fishery Sciences of China, 2016, 23(2): 336-343. [方进, 邓院生, 王俊, 等. 急性病毒性鲫鳃出血病的病理变化 [J]. 中国水产科学, 2016, 23(2): 336-343.]

[112]Zeng X T, Chen Z Y, Deng Y S,et al. Complete genome sequence and architecture of crucian carpCarassius auratusherpesvirus (CaHV) [J].Arch Virology,2016(161): 3577-3581.

[113]Sodhi A, Montaner S. Gutkind J Viral hijacking of Gprotein-coupled-receptor signalling networks [J].Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2004(5): 998-1012.

[114]Wang J, Gui L, Chen Z Y,et al. Mutations in the C-terminal region affect subcellular localization of crucian carp herpesvirus (CaHV) GPCR [J].Virus Genes,2016(52): 484-494.

[115]Beilstein F, Cohen G H, Eisenberg R J,et al. Dynamic organization of herpesvirus glycoproteins on the viral envelope revealed by super-resolution microscopy [J].PLoS Pathogens, 2019, 15(12): e1008209.

[116]Zhao Y H, Zeng X T, Zhang Q Y. Fish herpesvirus protein (CaHV-138L) can target to mitochondrial protein FoF1 ATPase [J].Virus Research, 2020(275): 197754.

[117]Wang Z H, Zhang Q Y. Characterization ofCarassius auratusherpesvirus ORF31R (CaHV-31R) and the encoded protein colocalize with cellular organs [J].Journal of Fisheries of China, 2019, 43(5): 1263-1270. [王子豪, 张奇亚. 鲫疱疹病毒ORF31R(CaHV-31R)的特征及其编码蛋白与细胞器共定位 [J]. 水产学报, 2019,43(5): 1263-1270.]

[118]Gao F X, Wang Y, Zhang Q Y,et al. Distinct herpesvirus resistances and immune responses of three gynogenetic clones of gibel carp revealed by comprehensive transcriptome [J].BMC Genomics, 2017(18): 561.

[119]Lu W J, Gao F X, Wang Y,et al. Differential expression of innate and adaptive immune genes in the survivors of three gibel carp gynogenetic clones after herpesvirus challenge [J].BMC Genomics, 2019(20): 432.

[120]Gao F X, Lu W J, Wang Y,et al. Differential expression and functional diversification of diverse immunoglobulin domain-containing protein (DICP) family in three gynogenetic clones of gibel carp [J].Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 2018(84): 396-407.

[121]Mou C Y, Wang Y, Zhang Q Y,et al. Differential interferon system gene expression profiles in susceptible and resistant gynogenetic clones of gibel carp challenged with herpesvirus CaHV [J].Developmental & Comparative Immunology, 2018(86): 52-64.

[122]Zang Z X, Dan C, Zhou L,et al. Function characterization and expression regulation of two different-sized 3’untranslated region-containing interferon genes from clone F of gibel carpCarassius auratus gibelio[J].Molecular Immunology, 2020(119): 18-26.

[123]Feckaninova A, Koscova J, Mudronova D. The use of probiotic bacteria againstAeromonasinfections in salmonid aquaculture [J].Aquaculture, 2017, 469(20): 1-8.

[124]Zorriehzahra M J, Delshad S T, Adel M,et al. Probiotics as beneficial microbes in aquaculture: an update on their multiple modes of action: a review [J].Veterinary Quarterly, 2016, 36(4): 228-241.

[125]Li T, Ke F, Gui J F,et al. Protective effect ofClostridium butyricumagainstCarassius auratusherpesvirus in gibel carp [J].Aquaculture International, 2019, 27(3):905-914.

[126]Ethier V. Monterey Bay Aquarium, Red swamp frayfish[C]. http://seafood.ocean.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Crawfish-Red-Swamp-China. 2013: 1-34.

[127]Longshaw M. Diseases of crayfish: A review [J].Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2011(106): 54-70.

[128]Baumgartner W A, Hawke J P, Bowles K,et al. Primary diagnosis and surveillance of white spot syndrome virus in wild and farmed crawfish (Procambarus clarkii,P.zonangulus) in Louisiana, USA [J].Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2009, 85(1): 15-22.

[129]Walker P J, Winton J R. Emerging viral diseases of fish and shrimpEmerging viral diseases of fish and shrimp[J].Veterinary Research, 2010, 41(6): 51.

[130]Manfrin C, Souty-Grosset C, Anastácio P,et al. Detection and control of invasive freshwater crayfish: from traditional to innovative methods [J].Diversity, 2019,11(1): 5.

[131]Soowannayan C, Nguyen G T, Pham L N,et al. Australian red claw crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus) is susceptible to yellow head virus (YHV) infection and can transmit it to the black tiger shrimp (Penaeusmonodon) [J].Aquaculture, 2015(445): 63-69.

[132]Pan Z H, Yang Z L, Lu C P. Diagnosis of white spot syndrome virus in farm crawfish in Anhui province and its epidemiological source [J].Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2013, 53(5): 492-497. [潘子豪, 杨政霖, 陆承平. 安徽地区小龙虾白斑综合征的诊断及朔源 [J]. 微生物学报, 2013, 53(5): 492-497.]

[133]Jiang L, Xiao J, Liu L,et al. Characterization and prevalence of a novel white spot syndrome viral genotype in naturally infected wild crayfish,Procambarus clarkii, in Shanghai, China [J].Virusdisease, 2017, 28(3): 250-261.

[134]Shi Z, Huang C, Zhang J,et al. White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) experimental infection of the freshwater crayfish,Cherax quadricarinatus[J].Journal of Fish Diseases, 2000, 23(4): 285-288.

[135]张奇亚, 柯飞. 淡水小龙虾线头病毒PCV-87R特异性序列及应用的制作方法 [P]. http://www.xjishu.com/zhuanli/27/201910307663.html, 2019.

[136]van Hulten M C W, Witteveldt J, Snippe M,et al. White spot syndrome virus envelope protein VP28 is involved in the systemic infection of shrimp [J].Virology, 2001,285(2): 228-233.

[137]Escobedo-Bonilla C M, Alday-Sanz V, Wille M,et al. A review on the morphology, molecular characterization,morphogenesis and pathogenesis of white spot syndrome virus [J].Journal of Fish Diseases, 2008, 31(1):1-18.

[138]Dieu B T, Marks H, Zwart M P,et al. Evaluation of white spot syndrome virus variable DNA loci as molecular markers of virus spread at intermediate spatiotemporal scales [J].Journal of General Virology, 2010, 91(5):1164-1172.

[139]Pradeep B, Shekar M, Karunasagar I,et al. Characterization of variable genomic regions of Indian white spot syndrome virus [J].Virology, 2008, 376(1): 24-30.

[140]Zimmer C. A Planet of Viruses (2nd Edition) [M].Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015: 104.

[141]Paez-Espino D, Eloe-Fadrosh E A, Pavlopoulos G A,et al. Uncovering earth’s virome [J].Nature, 2016(536):425-430.

[142]Lavigne R, Ceyssens P J. Family Myoviridae [M]//King A M Q, Adams M J, Carstens E B,et al(Eds.), Virus Taxonomy Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press,2012: 46-62.

[143]Zhang Q Y, Gui J F. One kind of strategic bio-resources that cannot be ignored——Freshwater and marine viruses and their roles in the global ecosystem [J].Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2009, 24(4): 520-526. [张奇亚, 桂建芳. 一类不可忽视的战略生物资源——淡水与海水中的病毒及其在生态系统中的作用 [J]. 中国科学院院刊, 2009, 24(4): 520-526.]

[144]Zimmerman A E, Howard-Varona C, Needham D M,etal. Metabolic and biogeochemical consequences of viral infection in aquatic ecosystems [J].Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2019, 18(41): 1-14.

[145]Guidi L, Chaffron S, Bittner L,et al. Plankton networks driving carbon export in the oligotrophic ocean [J].Nature, 2016(532): 465-470.

[146]Breitbart M, Bonnain C, Malki K,et al. Phage puppet masters of the marine microbial realm [J].Nature Microbiology, 2018, 3(7): 754-766.

[147]Brum J R, Ignacio-Espinoza J C, Roux S,et al. Patterns and ecological drivers of ocean viral communities [J].Science, 2015, 348(6237): 1261498.

[148]Schulz F, Roux S, Paez-Espino D, Jungbluth S,et al.Giant virus diversity and host interactions through global metagenomics [J].Nature, 2020, 578(7795): 432-436.

[149]Levasseur A, Bekliz M, Chabrière E,et al. MIMIVIRE is a defence system in mimivirus that confers resistance to virophage [J].Nature, 2016, 531(7593): 249-252.

[150]Fischer M G, Allen M J, Wilson W H,et al. Giant virus with a remarkable complement of genes infects marine zooplankton [J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010,107(45): 19508-19513.

[151]Lindell D, Jaffe J D, Coleman M L,et al. Genome-wide expression dynamics of a marine virus and host reveal features of co-evolution [J].Nature, 2007, 449(7158):83-86.

[152]Marston M F, Pierciey F J, Shepard A,et al. Rapid diversification of coevolving marineSynechococcusand a virus [J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(12):4544-4549.

[153]Doron S, Fedida A, Hernández-Prieto M A,et al. Transcriptome dynamics of a broad host-range cyanophage and its hosts [J].The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(6): 1437-1455.

[154]Kupczok A, Dagan T. Rates of molecular evolution in a marine synechococcus phage lineage [J].Viruses, 2019,11(8): 720.

[155]Hatzenpichler R, Krukenberg V, Spietz R L,et al. Nextgeneration physiology approaches to study microbiome function at single cell level [J].Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2020, 18(4): 241-256.

[156]Gao E B, Li S H, Lü B,et al. Analysis of the cyanophage (PaV-LD) infection in host cyanobacteria under different culture conditions [J].Acta Hydrobiologica Sinica, 2012, 36(3): 420-425. [高恶斌, 李三华, 吕波,等. 水华蓝藻噬藻体对不同条件培养的宿主细胞感染性分析 [J]. 水生生物学报, 2012, 36(3): 420-425.]

[157]Pinto D, Santos M A, Chambel L. Thirty years of viable but nonculturable state research: unsolved molecular mechanisms [J].Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 2015,41(1): 61-76.

[158]Li L, Mendis N, Trigui H,et al. The importance of the viable but non-culturable state in human bacterial pathogens [J].Frontiers in Microbiology, 2014(5): 258.

[159]Ayrapetyan M, Williams T, Oliver J D. Relationship between the viable but nonculturable state and antibiotic persister cells [J].Journal of Bacteriology, 2018,200(20): e00249-18.

[160]Ou T, Li S H, Liao X Y,et al. Cultivation and characterization of the MaMV-DC cyanophage that infects bloomforming cyanobacteriumMicrocystis aeruginosa[J].Virologica Sinica, 2013, 28(5): 266-271.

[161]Liao X Y, Ou T, Gao H,et al. Main reason for concentric rings plaque formation of virus infecting cyanobacteria (A-4L) in lawns ofAnabaena variabilis[J].Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2014, 54(2): 191-199. [廖湘勇,欧铜, 高宏, 等. 蓝细菌病毒A-4L在鱼腥藻 (Anabaena variabilis) 藻苔中形成同心圆噬斑的成因 [J]. 微生物学报, 2014, 54(2): 191-199.]

[162]Yoshida T, Nagasaki K, Takashima Y,et al. Ma-LMM01 infecting toxicMicrocystis aeruginosailluminates diverse cyanophage genome strategies [J].Journal of Bacteriology, 2008, 190(5): 1762-1772.

[163]Ou T, Gao X C, Li S H,et al. Genome analysis and gene nblA identification ofMicrocystis aeruginosamyovirus(MaMV-DC) reveal the evidence for horizontal gene transfer events between cyanomyovirus and host [J].Journal of General Virology, 2015, 96(12): 3681-3697.

[164]Ou T, Liao X Y, Gao X C,et al. Unraveling the genome structure of cyanobacterial podovirus A-4L with long direct terminal repeats [J].Virus Research, 2015(203): 4-9.

[165]Bertozzi Silva J, Storms Z, Sauvageau D. Host receptors for bacteriophage adsorption [J].FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2016, 363(4): 1-11.

[166]Xiong Z Z, Wang Y L, Dong Y L,et al. Cyanophage A-1(L) Adsorbs to lipopolysaccharides ofAnabaenasp.Strain PCC 7120 via the tail protein lipopolysaccharideinteracting protein (ORF36) [J].Journal of Bacteriology, 2019, 201(3): e516-e518.

[167]Gao E B, Gui J F, Zhang Q Y. A novel cyanophage with cyanobacterial non-bleaching protein a gene in the genome [J].Journal of Virology, 2012, 86(1): 236-245.

[168]Li S H, Gao E B, Ou T,et al. Cloning and expression analysis of major capsid protein gene, endopeptidase and holin gene of cyanophage PaV-LD [J].Acta. Hydrobiologica Sinica, 2013, 37(2): 252-259. [李三华, 高恶斌,欧铜, 等. 噬藻体PaV-LD主要衣壳蛋白、穿孔素和内肽酶基因的克隆及表达分析 [J]. 水生生物学报, 2013,37(2): 252-259.]

[169]Fridman S, Flores-Uribe J, Larom S,et al. A myovirus encoding both photosystem I and II proteins enhances cyclic electron flow in infected Prochlorococcus cells[J].Nature Microbiology, 2017, 2(10): 1350-1357.

[170]Sawa N, Tatsuke T, Ogawa A,et al. Modification of carbon metabolism inSynechococcus elongatusPCC 7942 by cyanophage-derived sigma factors for bioproduction improvement [J].Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2019, 127(2): 256-264.

[171]Xiao Y, Luo M, Hayes R P,et al. Structure basis for directional R-loop formation and substrate handover mechanisms in type I CRISPR-Cas system [J].Cell, 2017,170(1): 48-60.

[172]Niewoehner O, Garcia-Doval C, Rostøl J T,et al. Type III CRISPR-Cas systems produce cyclic oligoadenylate second messengers [J].Nature, 2017, 548(7669): 543-548.

[173]Yan W X, Hunnewell P, Alfonse L E,et al. Functionally diverse type V CRISPR-Cas systems [J].Science,2019, 363(6422): 88-91.

[174]Šulčius S, Šimoliūnas E, Alzbutas G,et al. Genomic characterization of cyanophage vB_AphaS-CL131 infecting filamentous diazotrophic cyanobacteriumAphanizomenon flos-aquaereveals novel insights into virusbacterium interactions [J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2019, 85(1): 1311-1118.

[175]Shmakov S, Smargon A, Scott D,et al. Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems [J].Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2017(15): 169-182.

[176]Marino N D, Zhang J Y, Borges A L,et al. Discovery of widespread type I and type V CRISPR-Cas inhibitors [J].Science, 2018, 362(6411): 240-242.

[177]Wang J P, Bai P, Li Q,et al. Interaction between cyanophage MaMV-DC and eightMicrocystisstrains, revealed by genetic defense systems [J].Harmful Algae,2019(85): 101699.

[178]Knott G J, Doudna J A. CRISPR-Cas guides the future of genetic engineering [J].Science, 2018, 361(6405):866-869.

[179]Salmond G P, Fineran P C. A century of the phage: past,present and future [J].Nature Reviews Microbiology,2015, 13(12): 777-786.

[180]Liao H K, Gu Y, Diaz A,et al. Use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system as an intracellular defense against HIV 1 infection in human cells [J].Nature Communications,2015(6): 6413.

[181]Gui J F, Bao Z M, Zhang X, J. Development strategy for aquaculture genetic breeding and seed industry [J].Chinese Journal of Engineering Science, 2016, 18(3): 8-14. [桂建芳, 包振民, 张晓娟. 水产遗传育种与水产种业发展战略研究 [J]. 中国工程科学, 2016, 18(3): 8-14.]

[182]Kauffman K M, Hussain F A, Yang J,et al. A major lineage of non-tailed dsDNA viruses as unrecognized killers of marine bacteria [J].Nature, 2018, 554(7691):118-122.

[183]Liu J, Yu C, Gui J F,et al. Real-time dissecting the entry and intracellular dynamics of single reovirus particle [J].Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018(9): 2797.

[184]Claussnitzer M, Cho J H, Collins R,et al. A brief history of human disease genetics [J].Nature, 2020,577(7789): 179-189.

[185]Yoshikawa G, Blanc-Mathieu R, Song C,et al. Medusavirus, a novel large DNA virus discovered from hot spring water [J].Journal of Virology, 2019, 93(8): 2130-2218.

[186]Iyer L M, Aravind L, Koonin E V. Common origin of four diverse families of large eukaryotic DNA viruses[J].Journal of Virology, 2001, 75(23): 11720-11734.

[187]Subramaniam K, Behringer D C, Bojko J,et al. A new family of DNA viruses causing disease in crustaceans from diverse aquatic biomes [J].mBio, 2020(11): 2938-3019.

[188]Wessner D R. The Origins of Viruses [J].Nature Education, 2010, 3(9): 37.

[189]Koonin E V, Yutin N. Origin and evolution of eukaryotic large nucleo-cytoplasmic DNA viruses [J].Intervirology, 2010, 53(5): 284-92.

[190]Roossinck M J. The good viruses: viral mutualistic symbioses [J].Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2011(9): 99-108.

[191]Engering A, Hogerwerf L. Pathogen-host-environment interplay and disease emergence [J].Emerging Microbes and Infections, 2013, 2(2): e5.

[192]Vörösmarty C J, McIntyre P B, Gessner M O,et al.Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity [J].Nature, 2010, 468(7321): 555-561.

[193]Song LS. An early warning system for diseases during mollusc mariculture: exploration and utilization [J].Journal of Dalian Ocean University, 2020, 35(1): 1-9.[宋林生. 海水养殖贝类病害预警预报技术及其应用[J]. 大连海洋大学学报, 2020, 35(1): 1-9.]

[194]Assefa A, Abunna F. Maintenance of fish health in aquaculture: review of epidemiological approaches for prevention and control of infectious disease of fish [J].Veterinary Medicine International, 2018, Article ID 5432497: 1-10.

[195]Jeney G. Fish Diseases: Prevention and Control Strategies [M]. London: Academic Press, 2017: 1-278.