Virulent Bacteria as ACo-factor of Colon Carcinogenesis: Evidence from Two Monozygotic Patients

Iradj Sobhani1 Emma Bergsten1 Cecile Charpy Denis Mestivier

Running title: Virulent Bacteria in CRC

Corresponding author: Prof. Iradj Sobhani, Email: iradj.sobhani@aphp.fr

Abstract

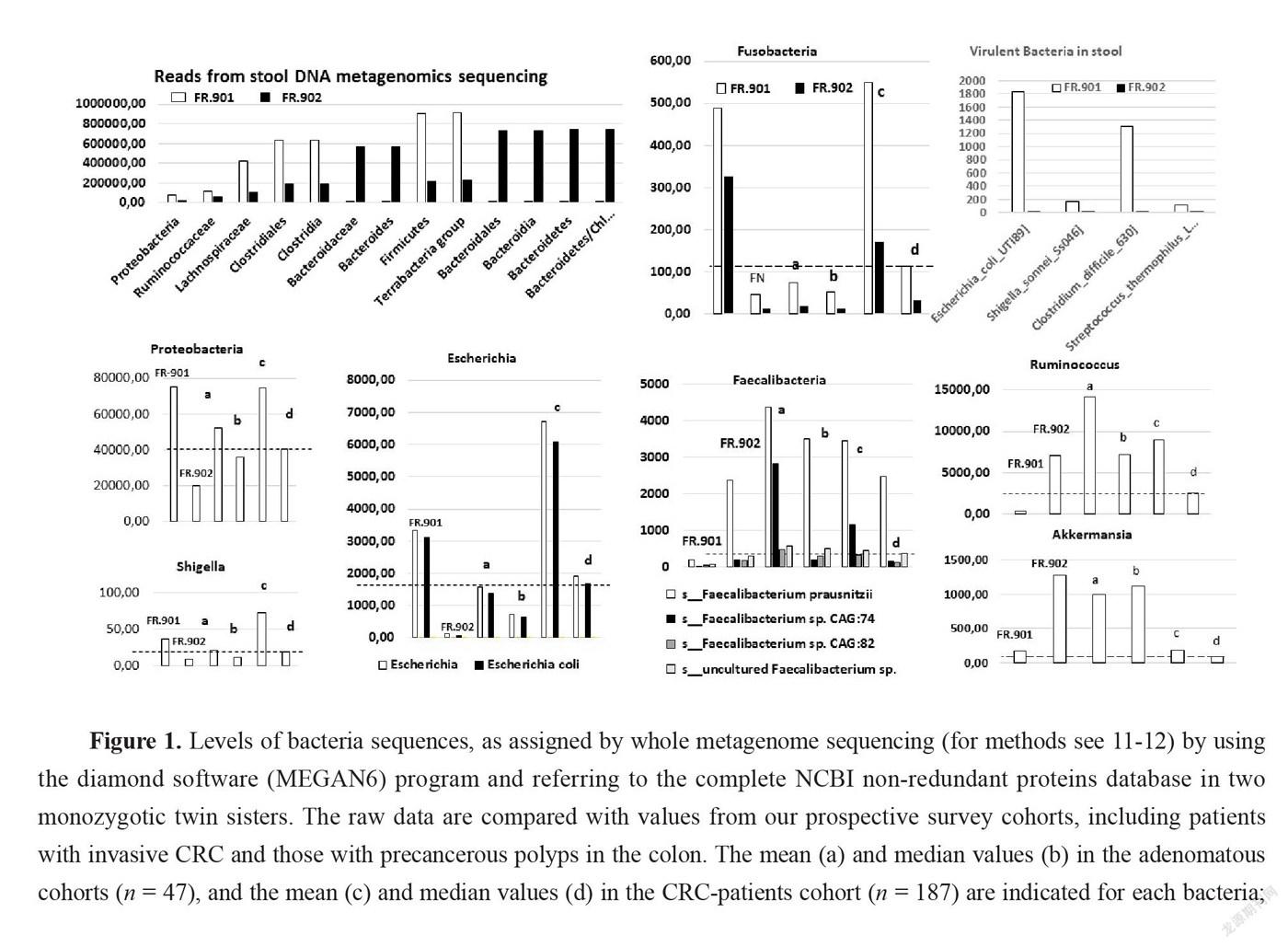

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is a common disease with a poor prognosis. CRC results from the accumulation of DNA alterations in colonocytes through a multistage carcinogenesis process. Most CRCs are related to the environment, which influences microbiota composition in the colon. Here we report the analysis of the gut microbiota of two monozygotic twin sisters, one of whom suffering from advance colorectal tumor-infiltrated by immunotolerant T cells. Comparative analysis highlights the profound disequilibrium of the composition of the gut microbiota of CRC-displaying twin with overexpression of virulent bacteria such as E. coli, Shigella, and Clostridium species in the CRC patient’s feces in contrast with low level of bacterial species such as Faecalibacterium and Akkermansia usually enriched in the healthy adults’ microbial flora at the expense of an over-representation of pathogenic bacterial species. The disequilibrium in microbiota of the CRC patient’s feces as compared to her monozygotic twin sister is linked with inflammatory and immune cell infiltrate in the patient’s tumor tissue.

Keywords:Cancer; colon; microbiota; immune cells; virulent bacteria

1. INTRODUCTION

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is one of the three most common cancers. There are more than 1.2 million new cases per year worldwide accounting for about 600,000 deaths [1]. CRC tumors result from the accumulation of DNA alterations that corrupt key signaling pathways in the colonic mucosa. This forms part of a multistage carcinogenesis process that involves hyperproliferation, the development of aberrant crypt foci (ACF), a transition from adenoma to carcinoma, tumor invasion, and metastasis [2-4]. Most CRCs are sporadic and less than 5% are hereditary [5], which suggests that environmental factors are the common underlying cause of CRC carcinogenesis. However, individuals with a first-degree relative affected by CRC have a two- to three-fold higherrisk of disease. Studies in twins have enabled estimation of the presumed role of genetics and environment in the occurrence of CRC [5]. The risk of colon cancer is higher in monozygotic than dizygotic twins [6].

Tissue-associated inflammation is a critical hallmark of cancer, and the resulting dysbiosisis a possible underlying cause of tumor aggressiveness. For example, Helicobacter pylori is responsible of chronic inflammation in the gastric mucosa, which leads to fundic gland atrophy, hypochloridria, and gastric cancer [7]. In addition, the presence of innate and adaptive immune cells, which are also recruited and modulated by dysbiosis in most human tumors, are features of cancer development and progression [8]. Particularly in CRCs resistance to immune check point targets might be due to dysbiosis [9].

Here, we report case observations of two monozygotic twin sisters, one of whom had an invasive carcinoma and her sister who was considered a control case. Data from their colonoscopies are linked to the recruitment of inflammatory or immune cells and to the role of virulent bacteria in feces. By comparing normal, adenomatous, and cancerous tissues, we show that high levels of tumor-infiltrated immunotolerant T cells are associated with elevated numbers of virulent bacteria and reduced numbers of immune-modulator bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium and Akkermansia, as well as with invasive neoplasia in the colon.

2. CASES

In April 2011, we examined Mrs. D., a 57-year-old woman without any personal or familial history of neoplasia, who had failed to participate in a mass screening program that was organized for asymptomatic individuals over the age of 50. She was referred to the gastroenterology department for a colonoscopy because of bowl disturbance and abdominal pain, anemia (10.9dg/mL) with microcytosis, and a diminished ferritin level. She was not taking any medicine prior to these symptoms. Therefore, she was invited to join our prospective CCR1 cohort study (design and preliminary results published elsewhere [10]). The physical examination was unhelpful, and blood tests showed normal kidney function but altered hepatic liver tests. She underwent a colonoscopy, which was performed under general anesthesia. She provided informed consent to be enrolled in microbiota translational studies, which required fresh stool collection three days before the colonoscopy. All additional investigations were performed on feces, the tumor, or normal tissues that were conserved until analysis under FR-901 reference in our biology collection bank and data set. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed abnormal thickening of the sigmoid wall and more than five abnormal nodular tumors in the liver. After cleansing, the colonoscopy showed a 5cm in diameter ulcerated tumor in the sigmoid that was suggestive of malignancy. Histopathology tissue examination taken during colonoscopy demonstrated an invasive adenocarcinoma (H&S staining), which was classified as Stage IV (according to TNM international classification) with Kras mutation and a low level of microsatellite instability (MSS) pattern. The patient underwent 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (Folfox4) chemotherapy plus anti VEGF-bevacizumab therapy. She told physicians that she had a monozygotic twin sister, Mrs. M., who was only taking hypertension drug therapy and had similarly failed to undergo screening for colon cancer. Thus, we asked Mrs. M., who had no digestive symptoms, to join our translational mass-screening trial (Clinical Trial Vatnimad NCT01270360). The patient similarly provided informed consent to allow research into her stool sample and deep analyses of her colonic tissues. Her colonoscopy showed two adenomatous polyps of 6 and 8mm in the right flexure and left colonic sites, respectively. They were removed and conserved in our biobank and data set until analysis under FR-902P1 and FR-902P2 codes, respectively. Both twins were living with their parents until the age of 26, both were married, and neither had children. Mrs. D died in September 2016 after forth-line therapy failure, and Mrs. M.’s last examination in March 2017 that did not showed any abnormality in the intestine.

3. METHODS

3.1 Microbiota Analysis

Stool samples were collected few days before the day of colonoscopy; samples of stool were collected and stored within 4 hours for DNA extraction using the GNOME® DNA Isolation Kit (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) as previously described [10-11]. We submitted stool samples from the two individuals to whole-genome shotgun metagenomic sequencing and results were compared to those of our whole survey cohort (For previous published results, see Ref 11-12). We compared sequences with comprehensive reference databases for taxonomic assignation using consensual pipelines, as described elsewhere [12]. To summarize, reads that went across quality checking (QC) and trimming were mapped to the NCBI non-redundant proteins database using diamond software (version 0.9.17) [13] and MEGAN6 [14], for taxonomy assignment and summarization at the species level. Less than 3% of each of these sequences were found to be unclassified or to correspond to contaminations by virus, Archaea, or Eukaryote and were consequently excluded. Briefly, levels of virulent proteins in two monozygotic women’s stool, as assigned by whole metagenome sequencing were estimated by using non-redundant proteins database. Taxonomic assignment of these virulence factors was established by mapping reads of each patient from the CCR1 cohort [11]to the virulence factor database (VFDB) [16] using the bowtie2 mapping software. Mapped reads for each type of virulence factor were expressed in counts per million (CPM) for further comparisons. Then raw data were compared with (mean and median) values from our prospective survey cohorts, including patients with invasive CRC (n = 187) and those with precancerous polyps (n = 47), in the colon, respectively.

3.2 Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of chemokines and cytokines

Total mRNA was prepared from tumours (CRC or polyps) and homologous normal specimens using Trizol reagent and following the manufacturer's protocol. Serial sections of 50 μ tissue were ground using stainless steel beads (5 mm) after adding cold Trizol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized in reverse transcriptase samples, each containing 2 μg total RNA isolated from tissues 16 units/μL Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), 4 μmol/L oligo(dT)12-18, and 0.8 mmol/L mixed dNTP (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech). Quantitative PCR was performed in a LightCycler 2.0 System (Roche Diagnostics) using a SYBR Green PCR kit or a Hybridization Probe PCR kit from Roche Diagnostics. Appropriate sequences of the primers and probes were chosen as described [17-18]. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), β2-microglobulin, or β-actin genes were considered as housekeeping genes (HKG). The β2-microglobulin gene was used as the control HKG for normalizing the result because it displayed the most stable expression in both tumoral and nontumoral specimens (data not shown). All PCR conditions were adjusted to obtain equivalent optimal amplification efficiency in the different assays. Real-time PCR was used for relative quantification of IL1, IL4, IL6, CXCR1, CD3, CD39, IL-8, IL-17, granzyme A,B, TNF, TGF, perforin, RORT, and FoxP3 mRNAs by using the SYBR Green PCR kit. Real-time PCR was used to provide absolute quantification of mRNAs by using a Hybridization Probe PCR kit. The copy number of the mRNA for all target genes and the HKG was determined by plotting the sample Ct values against the standard curve obtained with the corresponding “quantitative DNA standard” dilution series using LightCycler software 4.0. The abundance of the target gene mRNA was calculated as the copy number of the target gene per 106 copies of β2-microglobulin. All PCR experiments were done in duplicate.

3.3 Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Representative samples (n> 5 per tissue) from tumors (polyps and CRC) and normal homologous mucosa were selected for each case and paraffin-embedded 4-μm sections as described elsewhere [17-18]. Briefly, for immunoreactive staining, the sections were pretreated (boiling in buffer, pH 6.1 or 8, 1:20 dilution of horse serum in PBS for 20 min; Vector Laboratories). The serum was then removed and incubated overnight with appropriate antibodies for 1 to 2 hr depending on antibodies. The chromogen Sigma Fast 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma-Aldrich) was incubated with the tissue sections in the dark at room temperature for 4 min to visualize the antibody complex. The reaction was terminated by a water wash before being counterstained. For double staining IL17/CD3, the goat anti-human IL-17 antibody (diluted 1:40) was applied first and incubated for 2h hrs. Immunohistochemical staining was undertaken using a Vectastain AP kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and visualization was done with Naphtol/Fast Red(Sigma-Aldrich). Subsequently, a rabbit anti-human CD3 (diluted 1:50 in PBS, Dako, France) was incubated for 1 hr. Immunohistochemical staining was undertaken using ImmPRESS system (VectorLaboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) and visualization was done with DAB substrate. A semi quantitative morphometric analysis was performed for comparing immunoreactive cells between tissue samples.

4.RESULTS

4.1 Microbiota Analysis

Overall, bacteria sequences from stool did not show differences in total reads between CRC (n = 54,597,014) and no-CRC (n = 48,141,012) twin sisters when comparisons of taxa between the two sisters showed significant differences in terms of composition (Figure 1). However, according to principal component analysis (PCA) of all bacteria taxa the comparison between cohorts showed significant microbiota differences between CRC patients and colonic tumor-free individuals in our series.

With regards to the main bacteria genera usually associated with CRCs,and meta-analysis was used[15], various species of Bacteroides, Escherichia, Fusobacteria, Clostridia, and Proteobacteria were enriched in the CRC twin patient’s stool as compared to her no-CRC twin sister. This mirrored a concomitant impoverishment in stool of CRC patients from various species of Faecalibacterium and Ruminococcus (Figure 1). By filtering all virulence factors from the gut bacterial microbiota, we recorded 190 reads (0.0004%) in no-CRC patient versus 1,801 (0.002%) in CRC patient, which represented 50-fold enrichment in the CRC condition. Quantitative analysis here unveiled the enrichment in virulent proteins from Shigella, Escherichia, Clostridia, and Streptococcus species in the gut microbiota of patients from the CRC cohort, encompassing the twin suffering from CRC (Figure 1). This establishes that gut microbiota dysbiosis in colorectal cancer conditions leads to an enrichment of pathogenic bacteria encompassing Shigella, Escherichia, Clostridia, and Streptococcus species. This holds true from an example of monozygotic twin sisters up to the whole population.

4.2 Cytokines and Chemokines in Tissues

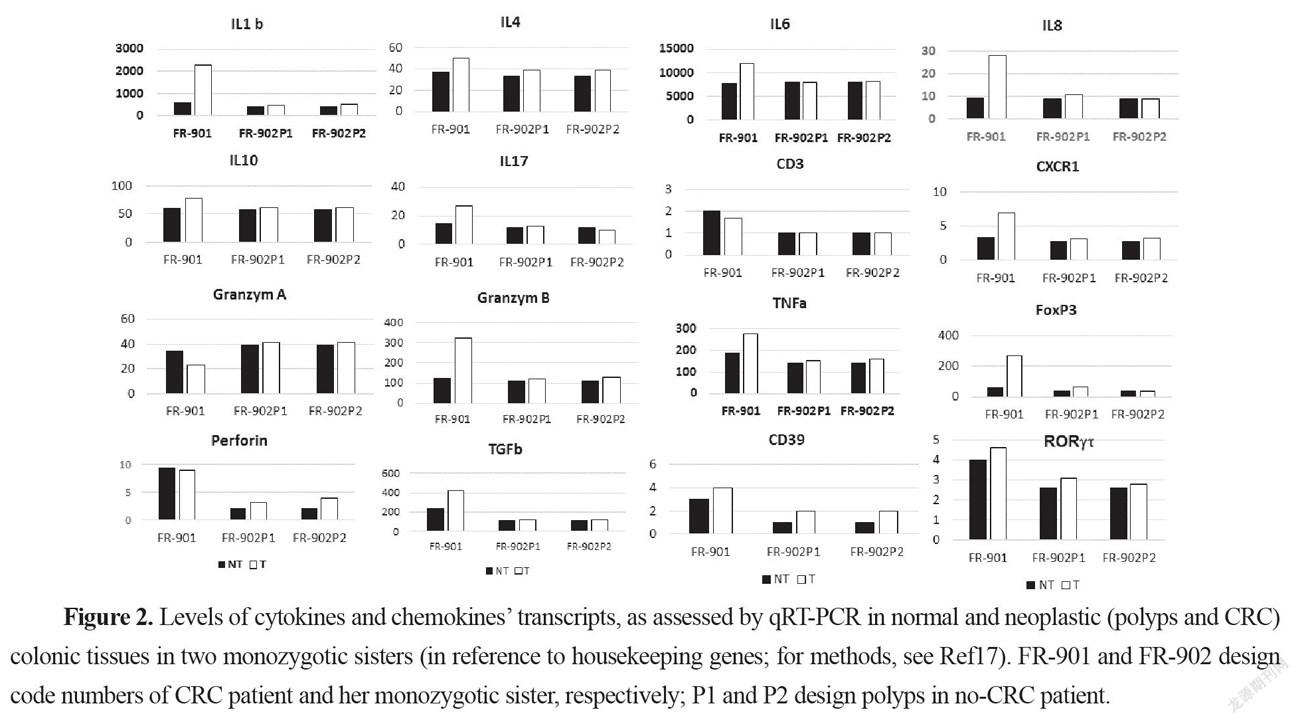

The mRNAs for IL1, IL4, IL6, IL-8, CXCR1, IL10, TNF, TGFβ, IL-17, FoxP3, RORT, granzyme B, and perforin were significantly more abundant in the CRC samples than in homologous normal tissue while similar amounts of these cytokines were found in two adenomatous as compared to the normal homologous tissues (Figure 2). In tumor tissues, relationships were observed between perforin, and granzyme B on the one hand and between IL-8 and CXCR1 on the other hand.

4.3 Inflammatory and Immune-cell Recruitment within the Tumor Tissues from Twins

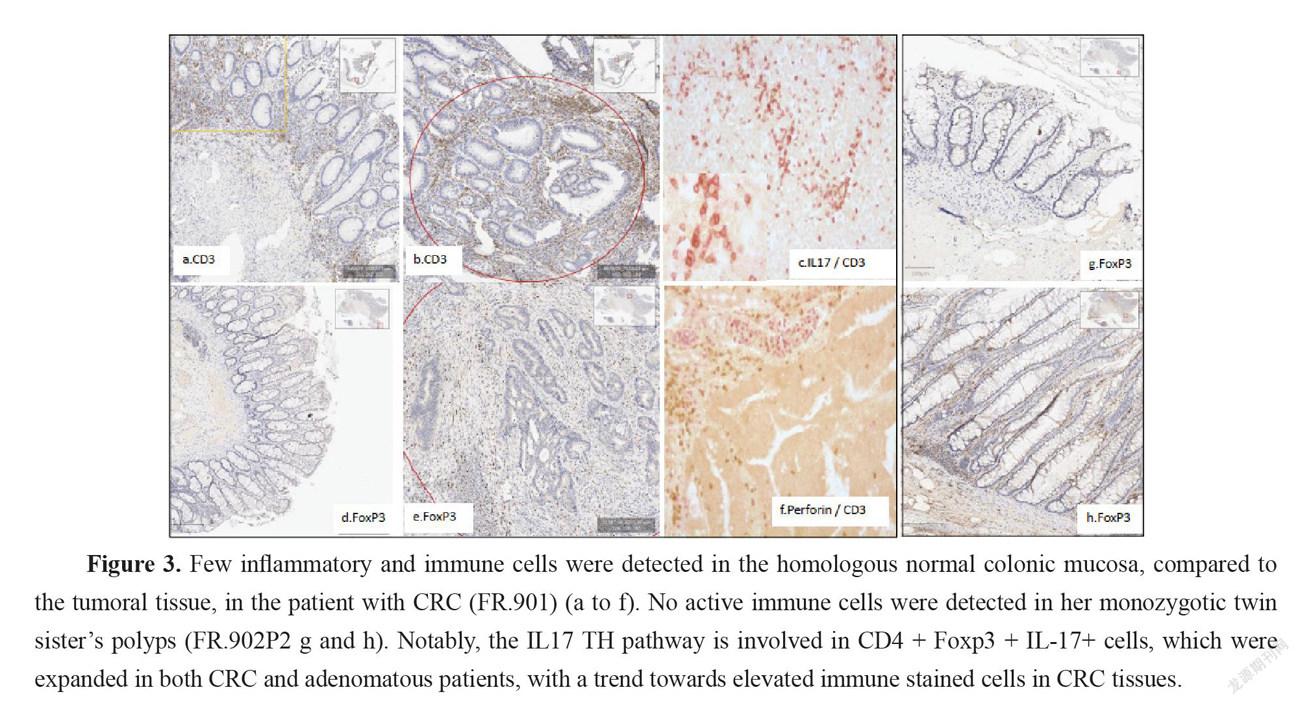

More mastocytes, monocytes and polynuclear inflammatory cells infiltrating CRC tissues were observed as compared to homologous normal tissues while such differences regarding myeloid inflammatory cell infiltrate were not observed in two no-CRC twin sister’s polyps (results not shown). Immunohistochemistry showed higher CD3, CD3-IL17, FoxP3, and RORT cells in CRC but not in adenomatous tissues. Among the inflammatory and immune-cell infiltrates within the mucosa (Figure 3), markers of cytotoxic response, such as Granzyme A and B, perforin, and ROR, were not significantly enhanced in tumor tissues, despite a trend toward augmentation (Figure 2). IL-17 and perforin immunoreactive cells were rarely detected in adenomatous or in normal tissues in the lamina propria. However, their numbers were always higher in sections of CRC tissues than in those of homologous normal tissues. Expressions of IL-17 and perforin on immunohistochemistry were consistent with those of RT-PCR.

5.DISCUSSION

Here we report gut microbiota differences in two twin sisters one of them presenting with a colonic cancer and one with polyps, a precancerous condition in the colon. If risk factors were independent from the environment, these two monozygotic sisters should have developed the disease at the same age. The fact that the two sisters had different microbiota suggests that the environment might be involved in cancer development and was a potential risk contributor in one of two sisters. The interindividual differences that account for the environment’s role have been estimated as reaching 15% [6]. The impact of the environment may be relied by the microbiota. This is the reason for which we indicated also mean and median values of our prospective survey cohorts with CRC or with polyps. Indeed, based on PCA analysis these cohorts displayed different microbiota composition in stool. Similarly, levels of main bacteria which were measured in stool, showed significantly different bacteria compositions between the two twin sisters. Further, based on metagenomic gene proteins, virulent proteins were found significantly different in two twin sisters; the values were close to the means we measured in polyp or CRC patient cohorts, respectively. Then we showed that pathogenic virulent bacteria as estimated from virulent protein core constitute the main part of this difference in two twin sisters, with higher levels of virulent bacteria in the CRC patient than in individual with polyps. Since tissue-adherent bacteria is substantially influenced by those of the stool [19], we hypothesized that patients with over expression of virulent bacteria might have higher inflammatory-cell infiltrate in their tumoral mucosa. Thus, type and function of myeloid, macrophages and T regulatory cells were analyzed in CRC tissues and in polyps by using IHC and qRT-PCR for the quantification of cells and chemokines, respectively. Production of molecules such as IL-6, TNF-α, suggests strongly inflammation in the tissue has a substantial macrophage involvement. Although we noticed more monocytes and polynuclear inflammatory cells infiltrating CRC tissues as compared to the homologous normal tissues, we could not determine whether M1 or M2 macrophages are involved in the CRC tissue. IL10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine acts through STAT3 for enhancing carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis in the intestine [20]. This cytokine is currently found higher in CRC tissue than in normal homologous, but not in no-CRC twin sister’s polyps. This suggests strongly that anti-inflammatory transcription factor Stat3 in macrophages is a result of chronic inflammatory response in the colon enhancing the risk of invasive adenocarcinoma [21] in CRC twin. Briefly, these changes in the macrophage-related cytokine levels in CRC tissue might cause tumor initiation by creating a mutagenic microenvironment through alterations in the microbiome and barrier functions [20-21]. In addition, by screening immune cells we showed clearly TH1 and TH17 pathways were stimulated in CRC tissues, when patterns in the polyps resembled normal colonic tissue (Figure 3). Interestingly, microbiota considered as a source of stimulation of inflammatory response in the colonic mucosa, revealed that less anti-inflammatory bacteria, such as Faecalibacterium and Eubacterium, were associated with overexpression of virulent bacteria such as E. coli, Shigella, and Clostridium species in the CRC patient’s stool (Figure 1) than in her no-CRC sister’s feces. Whether the carcinogenesis is directly linked to this imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory bacteria or the result of a failed immune response to no microbial factors (e.g., chemical carcinogenic substances) has yet to be determined. However, this core is also linked to inflammation and immune response in the tumor, which may involve an epigenetic pathway [12]. Nevertheless, several bacteria that are clustered within a community may be the cause of immunotolerant cell recruitment within tumor tissues. Overproduction of IL17 can lead to disease exacerbation. Relative concentrations of IL6 and TGFin tumor tissues balance the differentiation of coexisting CD4 + RORt + Th-17 cells and regulatory CD4 + FoxP3 + RORt + IL17-negative T cells. This ratio has been proposed to play a role in the regulation of immunoreactivity [22]. Additionally, T cells are components of the adaptive immune system. Thus, less immunogenic cancer cells escape T cells’ immune control and are able to survive a process called cancer immune editing [18; 23], which consists in cancer cells adopting an immune-resistant phenotype [9]. Cells then develop a mechanism able to prevent the local cytotoxic response of effector T cells as well as other cells, including NK cells and tumor-associated macrophages in the CRC twin case (as compared to her no-CRC sister’s polyps, FR-902P1&P2). Tregs could be responsible for suppressing the priming activation and cytotoxicity of other effector immune cells, such as TH1, macrophages, and neutrophils despite their overexpression in the CRC tissue. This mechanism is orchestrated by the producer of immunosuppressive molecules, such as IL10 and TGF, currently overexpressed in CRC tissue. Tregs suppress T-cell activation, which has been shown to worsen patient outcomes [18]. Increases in the mutation burden and heterogeneity of neoantigens in vivo, as well as the priming of a new anti-tumor T-cell repertoire, results from the inactivation of the DNA repair system in colorectal cancer [24]. Although stigmata of immune anti-tumor response (i.e., Perforin, CD39, RORt) could be observed in the CRC patient’s tumor tissue in the present observation, cytotoxicity was not deemed likely to sufficiently imprint longer survival [9; 25].

Interestingly, more oral-cavity pathobionts have currently been detected in CRC patients’ microbiota, as reported in several other studies [26]. The species of Fusobacterium, such as F. nucleatum, which we found to be enriched in the CRC patient (Figure 1), has been shown to be involved in a tumor-immune evasion mechanism, through which tumors exploit the Fap2 protein of the bacterium to inhibit immune-cell activity [27]. Together, the community of oral-cavity bacteria stimulate IL17-producing cells during periodontitis [28]. The main difference between our two patients’ microbiota concerned the virulent bacteria community (Figure 1). It is interesting to note that, among the virulent bacteria, T-helper 1 inflammatory responses in the gut [29] in our CRC patient can be attributed to a bacterium such as Klebsiella, rather than to others such E. coli or C. difficilethat do not trigger a TH1 response. The diminished levels of Rhuminococcus, Faecalibacteria and Akkermansia in the CRC patient, compared to her sister, suggest that diminution of these bacteria may account for a favored immune-response shift from immunotoxicity to tolerance. Notably, Bifidobacterium levels were similar in the two sisters’ stools, which suggests that the bacterium in solo might not protect against the occurrence of adenomatous tissues, in which cytokines of TH1 and TH2 were detected in similar levels to those of the normal colonic mucosa of the two individuals (Figure 2).

Acknowledgment: We thank Dr. Emmanuel Lemichez and Dr. Amel Mettouchi (Département de Microbiologie, Unité des toxines bactériennes, Institut Pasteur de Paris) for advices and fruitful discussions on virulence factors from pathogenic bacteria. We thank Dr. Aloulou and Dr. Chaumette for their helpful contribution for qRT-PCR and IHC.

This study is performed with financial support of Université Paris Est Creteil (UPEC), PHRC (Vatnimad) of French, and French government as well as by SNFGE (French society of Gastroenterology Commad Support 2019)

REFERENCE

[1] Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics[J]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69-90.

[2] Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer[J]. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330-337.

[3] Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, Preisinger AC, Leppert M, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development[J]. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(9):525-532.

[4] Jass JR. Classification of colorectal cancer based on correlation of clinical, morphological and molecular features[J]. Histopathology. 2007;50(1):113-130.

[5] Foulkes WD. Inherited susceptibility to common cancers[J]. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(20):2143-2153.

[6] Graff RE, Möller S, Passarelli MN, Witte JS, Skytthe A, Christensen K, et al. Familial Risk and Heritability of Colorectal Cancer in the Nordic Twin Study of Cancer[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(8):1256-1264.

[7] Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer[J]. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(11):784-789.

[8] Li S, Konstantinov SR, Smits R, Peppelenbosch MP. Bacterial Biofilms in Colorectal Cancer Initiation and Progression[J]. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23(1):18-30.

[9]Seow HF,Yip WY,Fifis T. Advances in targeted and immunobased therapies for colorectal cancer in the genomic era[J].OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9(2016):1899-1920.

[10] Sobhani I, Tap J, Roudot-Thoraval F, Roperch JP, Letulle S, Langella P, et al. Microbial Dysbiosis in Colorectal Cancer (CRC) Patients[J]. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16393.

[11] Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Costea PI, et al. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer[J]. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:766.

[12] Sobhani I, Bergsten E, Couffin S, Amiot A, Nebbad B, Barau C, et al. Colorectal cancer-associated microbiota contributes to oncogenic epigenetic signatures[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(48):24285-24295.

[13] Huson D, Beier S, Flade I, Gorska A, El-Hadidi M, Mitra S, Ruscheweyh H, Tappu RD. MEGAN Community Edition - Interactive exploration and analysis of large-scale microbiome sequencing data[J].PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12(6):e1004957.

[14] Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and Sensitive Protein Alignment using DIAMOND[J]. Nature Methods. 2015;12:59-60.

[15] Liu B, Zheng DD, Jin Q, Chen LH and Yang J. VFDB 2019: a comparative pathogenomic platform with an interactive web interface[J]. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):687-692.

[16] Duvallet C, Gibbons SM, Gurry T, Irizarry RA, Alm EJ. Meta-analysis of gut microbiome studies identifies disease-specific and shared responses[J]. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1784.

[17] Le Gouvello S, Bastuji-Garin S, Aloulou N, Mansour H, Chaumette M-T, Berrehar F, et al. High prevalence of Foxp3 and IL17 in MMR-proficient colorectal carcinomas[J]. Gut. 2008;57(6):772-779.

[18] Aloulou N, Bastuji-Garin S, Le Gouvello S, Abolhassani M, Chaumette MT, Charachon A, Leroy K, Sobhani I. Involvement of theleptinreceptor in the immune response in intestinal cancer[J].Cancer Res. 2008;68(22):9413-22.

[19] Arthur JC, Jobin Ch. The complex interplay between inflammation, the microbiota and colorectal cancer[J]. Gut Microbes. 2013;4(3):253-258.

[20] Dedon PC, Tannenbaum SR. Reactive nitrogen species in the chemical biology of inflammation[J]. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;423(1):12-22.

[21] Dejea CM, Sears CL. Do biofilms confer a pro-carcinogenic state? Gut Microbes[J]. 2016;7(1):54-57.

[22] Lochner M, Peduto L, Cherrier M, Sawa S, Langa F, Varona R, et al. In vivo equilibrium of proinflammatory IL-17+ and regulatory IL-10+ Foxp3+ RORgamma t+ T cells[J]. J Exp Med. 2008;205(6):1381-1393.

[23] Teng MWL, Kershaw MH, Moeller M, Smyth MJ, Darcy PK. Immunotherapy of cancer using systemically delivered gene-modified human T lymphocytes[J]. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15(7):699-708.

[24] Dominguez-Valentin M, Sampson JR, Seppälä TT, Ten Broeke SW, Plazzer J-P, Nakken S, et al. Cancer risks by gene, age, and gender in 6350 carriers of pathogenic mismatch repair variants: findings from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database[J]. Genet Med. 2020;22(1):15-25.

[25] Simoni Y, Becht E, Fehlings M, Loh CY, Koo S-L, Teng KWW, et al. Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates[J]. Nature. 2018;557(7706):575-579.

[26] Schmidt TS, Hayward MR, Coelho LP, Li SS, Costea PI, Voigt AY, et al. Extensive transmission of microbes along the gastrointestinal tract[J]. eLife.2019; 8: e42693.

[27] Gur C, Ibrahim Y, Isaacson B, Yamin R, Abed J, Gamliel M, et al. Binding of the Fap2 protein of Fusobacterium nucleatum to human inhibitory receptor TIGIT protects tumors from immune cell attack[J]. Immunity. 2015;42(2):344-355.

[28] Xiao L, Zhang Q, Peng Y, Wang D, Liu Y. The effect of periodontal bacteria infection on incidence and prognosis of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99(15):e19698.

[29] Gharaibeh RZ, Jobin C. Microbiota and cancer immunotherapy: in search of microbial signals[J]. Gut. 2019;68(3):385-388.

- Trends in Oncology的其它文章

- Analysis of Retropubic and Laparoscopic Radical Prostatectomy for Localized Prostate Cancer

- Diagnostic Value of Conventional MRI and DWI for Atypical Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma(PCNSL)

- Diagnostic Value of Electrocardiogram(ECG) in Aortic Dissection Aneurysm

- Analysis of Pain Assessment and Nursing Measures for Patients with Advanced Hematological Tumors