Transarterial chemoembolization with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy plus S-1 for hepatocellular carcinoma

Jian-Hai Guo, Shao-Xing Liu, Song Gao, Fu-Xin Kou, Xin Zhang, Di Wu, Xiao-Ting Li, Hui Chen, Xiao-Dong Wang, Peng Liu, Peng-Jun Zhang, Hai-Feng Xu, Guang Cao, Lin-Zhong Zhu, Ren-Jie Yang, Xu Zhu

Abstract

Key words: Hepatocellular carcinoma; Advanced; Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; Transarterial chemoembolization; Prognosis; Efficacy

INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer was ranked seventh by number of incident cases and fourth by number of cancer-related deaths worldwide in 2016, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) representing the most prevalent type of liver cancer[1,2]. China currently accounts for approximately 50% of the world’s HCC patients, and the high prevalence of chronic hepatitis in this country is thought to be the dominant etiological factor[3,4]. In China, HCC is the second and third most common cause of cancer-related mortality in males and females, respectively[4]. Unfortunately, most patients with HCC are diagnosed at an intermediate or advanced stage at which they are ineligible for potentially curative treatments such as surgical resection and liver transplantation[5,6]. In particular, the prognosis for patients with advanced HCC characterized by vascular tumor invasion and/or extrahepatic metastasis [equal to Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage C or D[7]is almost always very poor[8,9].

Sorafenib, a small molecule inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor, is widely recommended for the treatment of advanced HCC based on the results of two phase III trials[10,11]. However, several limitations, such as a relatively low response rate, adverse events (AEs) and relatively high cost, are reported to limit the application of sorafenib in clinical practice, especially in Asia[10,12,13]. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) has been widely adopted as a treatment for patients with intermediate stage HCC and has also been investigated in patients with advanced HCC, including with portal vein invasion, with equivocal results[14,15]. It is hypothesized that the hypoxic injury to tumor cells caused by TACE leads to increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is a driving factor behind tumor recurrence. Therefore, TACE in combination with sorafenib has been explored. A recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that TACE and TACE-sorafenib may improve 1-year survivalversussorafenib monotherapy in patients with advanced HCC but did not show a significant difference between these approaches[16]. In addition, the tolerability of sorafenib often leads to dose reductions and interruptions when used in combination with TACE, limiting the effectiveness of this treatment strategy[17-20]. Therefore, further optimization of TACEbased approaches for advanced HCC is required.

Growing evidence suggests that combining TACE with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) may provide additional therapeutic benefit for patients with advanced, unresectable HCC[21]. HAIC can significantly increase the local dose of chemotherapeutic agents in the liver and reduce generalized side effects[22,23]. One commonly used chemotherapeutic agent in HAIC procedures is oxaliplatin, which has been shown to be effective and generally well tolerated; previous research indicates that oxaliplatin-based HAIC is tolerable and has potent anti-tumor activity against advanced HCC[24-26]. A study by Gaoet al[21]showed that combining TACE with HAIC was more effective than TACE alone in patients with intermediate stage HCC. In addition, as access to sorafenib in China is limited for many patients, we also investigated S-1, a composite preparation of a fluorouracil prodrug, which has proven to be a convenient oral chemotherapeutic agent with definite efficacy against advanced unresectable HCC[27,28]. Therefore, we designed this prospective randomized study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of treatment with TACE followed by oxaliplatin-based HAIC, with or without oral S-1, in advanced-stage HCC with portal vein invasion or extrahepatic metastasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patients

This was a single-center, open-label, prospective, randomized controlled trial conducted between December 2013 and September 2017 with follow-up until November 2018. The study totally included 117 patients aged ≥ 18 years with histologically or clinically diagnosed advanced HCC with portal vein invasion or extrahepatic metastasis (BCLC stage C). Clinical diagnosis of HCC was based on the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guideline criteria[29]. Eligible patients were also required to have Child-Pugh class A or B liver function, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 1, at least one measurable lesion according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0, life expectancy ≥ 12 wk, adequate organ function (hemoglobin ≥ 90 g/L, white blood cell count ≥ 3.0 × 109/L, absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1.5 × 109/L, platelet count ≥ 60 × 109/L, serum albumin level > 20 g/L, aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase < 5 times the upper limit of normal, total bilirubin serum levels < 3 times the upper limit of normal, creatinine clearance rate ≤ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and international normalized ratio < 2.3 or partial prothrombin time < 1.5 times the upper limit of normal), and not previously received TACE, HAIC or chemotherapy. Key exclusion criteria were early- or middle-stage HCC, any contraindication to TACE (poor liver function, portal obstruction of at least three segmental branches), advanced cardiac or pulmonary disease and severe renal function impairment, a known medical history of human immunodeficiency virus infection, other invasive malignant diseases and pregnant or breastfeeding women. All recruited patients with hepatitis B virus-related HCC received pre-emptive antiviral therapy.

朗读注于目,闻于耳,记于心,是一种复杂的心智过程,它有助于学生掌握每个汉字的音、形、义;更有助于加深学生对词语的理解与运用。当学生在能读出词语所表达的韵味、句子所呈现的意境时,教师就要趁热打铁,对学生的朗读进行激励性评价。当学生能工工整整,优美地将生字写在田字格中,教师就要将学生的优秀作品展示给大家看,调动学生的积极性。

Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants before entering the study. The clinical trial protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital, and the trial was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Randomization and treatments

Participants were randomized 1:1 to receive TACE followed by oxaliplatin-based HAIC plus oral S-1 (TACE/HAIC + S-1) or TACE followed by oxaliplatin-based HAIC (TACE/HAIC). Random assignment was generated by a statistician from our hospitalviaa computer-generated randomization sequence and without stratification. Treatments were applied every 6 wk until disease progression, death or intolerable toxicity was observed.

TACE

Each patient underwent angiographyviathe femoral artery using Seldinger’s technique. Arteriography was routinely performed to collect information about the number, type and location of the tumors and feeding arteries, as well as the presence of vascular anatomic variations. After visualization of the arterial distribution and the portal system in the reflux phase for each individual patient, the most appropriate TACE procedure was selected. The feeding arteries to the lesion were catheterized as selectively as possible by using a highly flexible coaxial catheter (Renegade Hi Flo, Boston Scientific, Boston, MA, United States/Stride ASAHI INTECC, Seto, Japan). The chemoembolization procedure comprised injection of iodized oil (Lipiodol; Laboratoire Andre Guerbet, Aulnay-sous-Bois, France) mixed with 20–40 mg epirubicin hydrochloride (Main Luck Pharmaceutical, Shenzhen, China) as an emulsion into segmental or subsegmental tumor-feeding arteries. For patients with a hepatic arteriovenous fistula, sponge particles (Jinling, Nanjing, China) were used to block the fistula before the infusion of iodized oil.

HAIC

HAIC was performedviaa catheter. The coaxial catheter was retained in the proper hepatic artery or the left or right hepatic arterial branch following TACE. Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin®; Sanofi S.A., Paris, France) 85 mg/m2was continuously infused over 4 hoursviaarterial pumping on day 1. After HAIC was completed, the catheter and sheath were removed. Repeated catheterization was performed in the next treatment cycle.

Oral S-1

S-1 (TS-1®; Taiho Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) 60 mg was given orally twice daily on days 2–15, initiated from the 2ndd after HAIC, and then patients were allowed to rest for 1 wk. Depending on the TACE and HAIC interval, every 3 wk constituted a course.

Study endpoints and measurements

The primary endpoint was initially designed to be time-to-progression (TTP). However, during the study a large proportion of patients died from liver function failure before tumor progression occurred and not enough progression events were observed for a meaningful estimate of TTP. Therefore, the primary endpoint was changed to progression-free survival (PFS). Progression was defined as progressive disease by an independent radiologic review according to modified RECIST or death from any cause. PFS was defined as the interval between the first TACE treatment and progression or death resulting from any cause.

Secondary endpoints included overall survival (OS), tumor objective response rate (ORR) defined as the proportion of patients achieving a complete (CR) or partial response (PR), disease control rate (DCR) defined as the proportion of patients achieving CR, PR or stable disease (SD) and safety. OS was defined as the interval between the first TACE treatment and death or final follow-up. All tumor response rates were evaluated according to modified RECIST criteria. Adverse reactions were evaluated and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 4.0). Peripheral neuropathy was graded according to a modified Levi scale.

Physical, clinical, enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging and laboratory tests were performed at baseline and at the start of each treatment cycle during the treatment phase. All patients were followed every 2 mo until death or until their final follow-up visit.

Statistical analyses

The study sample size was calculated based on the assumption that the median TTP in patients with advanced HCC receiving TACE followed by HAIC would be 4.0 mo and that adding S-1 would improve the median TTP to 6.5 mo. To detect this difference with 70% power and a 2-sided α of 0.05, 100 participants would be required, with an enrollment period of 24 mo and a follow-up period of 12 mo. Based on an estimated dropout rate of 5%, the target enrollment was set at 110 participants (55 per group).

For all statistical tests,Pvalues < 0.05 were considered significant. Depending on data normality, two-independent-samplesttests or Mann-WhitneyUtests were used to assess differences in continuous variables between the groups. Theχ2test was used to assess between group differences in categorical variables. Tumor response rates were compared using the two-sided Fisher’s exact test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate estimates of PFS and OS, and data were compared using the log-rank test.

Exploratory univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to investigate the association between patient demographic and baseline characteristics and survival outcomes (PFS and OS). Any factors that were statistically significant at aPvalue < 0.10 in the univariate analysis were candidates for entry into the multivariate model. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 22; IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, United States). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Xiao-Ting Li from our hospital.

RESULTS

Study participants

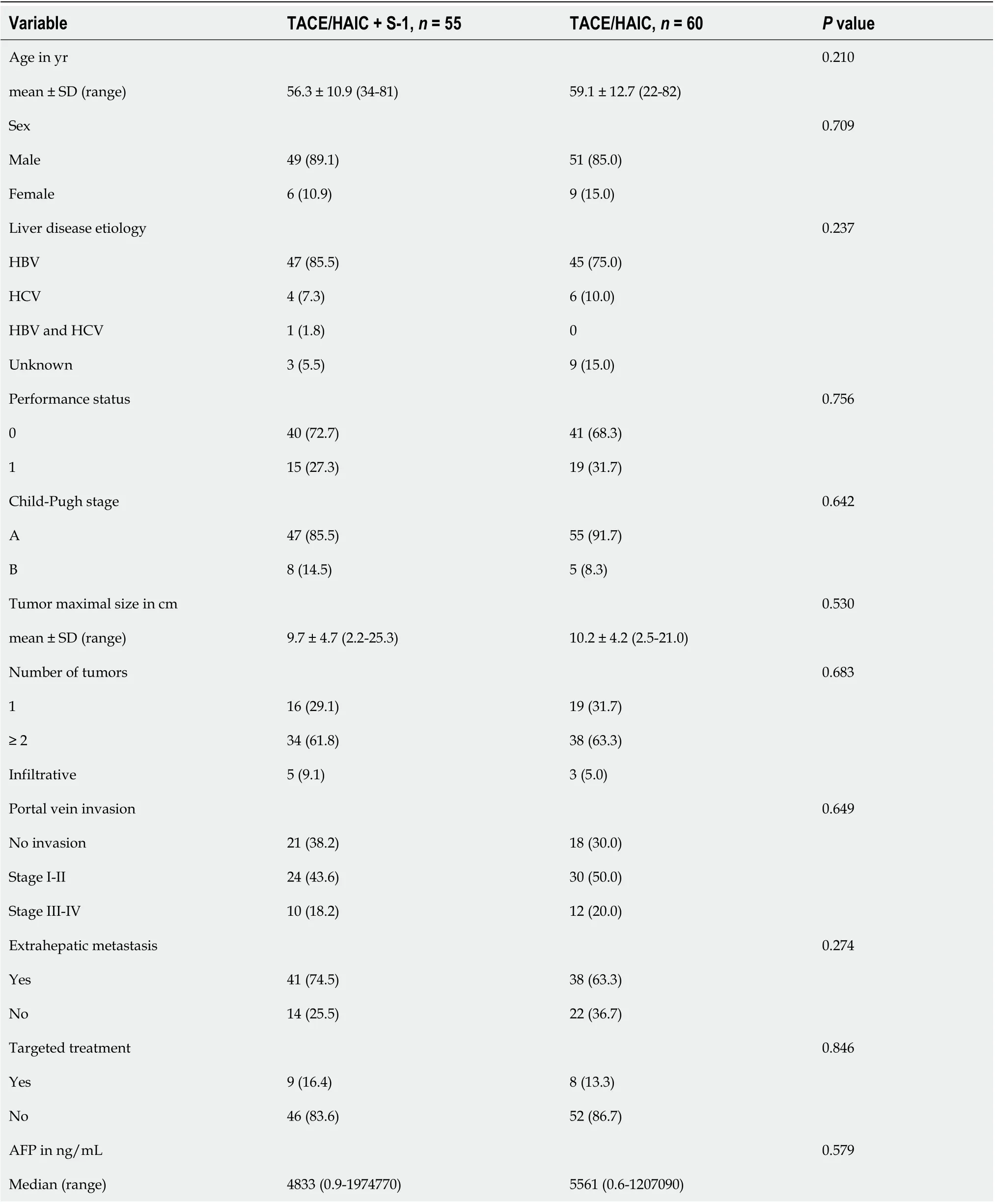

Between December 2013 and September 2017, 230 patients were screened, and 117 were randomly assigned to TACE/HAIC + S-1 (n= 56) or TACE/HAIC (n= 61) (Figure 1). Two participants withdrew consent before receiving treatment (one patient in each treatment group) and were therefore excluded from final analysis. Baseline characteristics were comparable between the two treatment groups (Table 1). Overall, participants were predominantly male and infected with HBV, and all participants had portal vein invasion or extrahepatic metastasis; 76/115 (66.1%) patients had portal vein invasion, 79/115 (68.7%) patients had extrahepatic metastasis and 40/115 (34.8%) patients had both portal vein invasion and extrahepatic metastasis. Extrahepatic metastasis sites included retroperitoneal lymph nodes (50 patients), lungs (18 patients), adrenal glands (10 patients), bones (8 patients) and other sites (6 patients). Ten patients had at least two sites of extrahepatic metastases.

Treatment exposure

The total number of cycles of treatment received was 150 and 163 for patients in the TACE/HAIC + S-1 and TACE/HAIC groups, respectively. Patients in both groups received a median of two cycles (1−9cycles) of TACE and HAIC. Curative surgical resection was conducted for 1/55 (1.8%) patient in the TACE/HAIC + S-1 group and 2/60 (3.3%) patients in the TACE/HAIC group following downstaging. TACE combined with local ablation was conducted for 8/55 (14.5%) patients in the TACE/HAIC + S-1 group and 9/60 (15.0%) patients in the TACE/HAIC group. TACE combined with radioactive particle implantation was conducted for 1/60 (1.7%) patient in the TACE/HAIC group.

Tumor response

Numerically higher ORR and DCR were observed for patients receiving TACE/HAIC + S-1 than those receiving TACE/HAIC (30.9%vs18.4%,P= 0.176 and 72.7%vs56.7%,P= 0.109, respectively). Rates of CR, PR, SD and progressive disease in the TACE/HAIC + S-1 group were 7.3%, 23.6%, 41.8%, 27.3%, respectively, and in the TACE/HAIC group were 6.7%, 11.7%, 38.3%, 43.3%, respectively (Table 2).

Survival

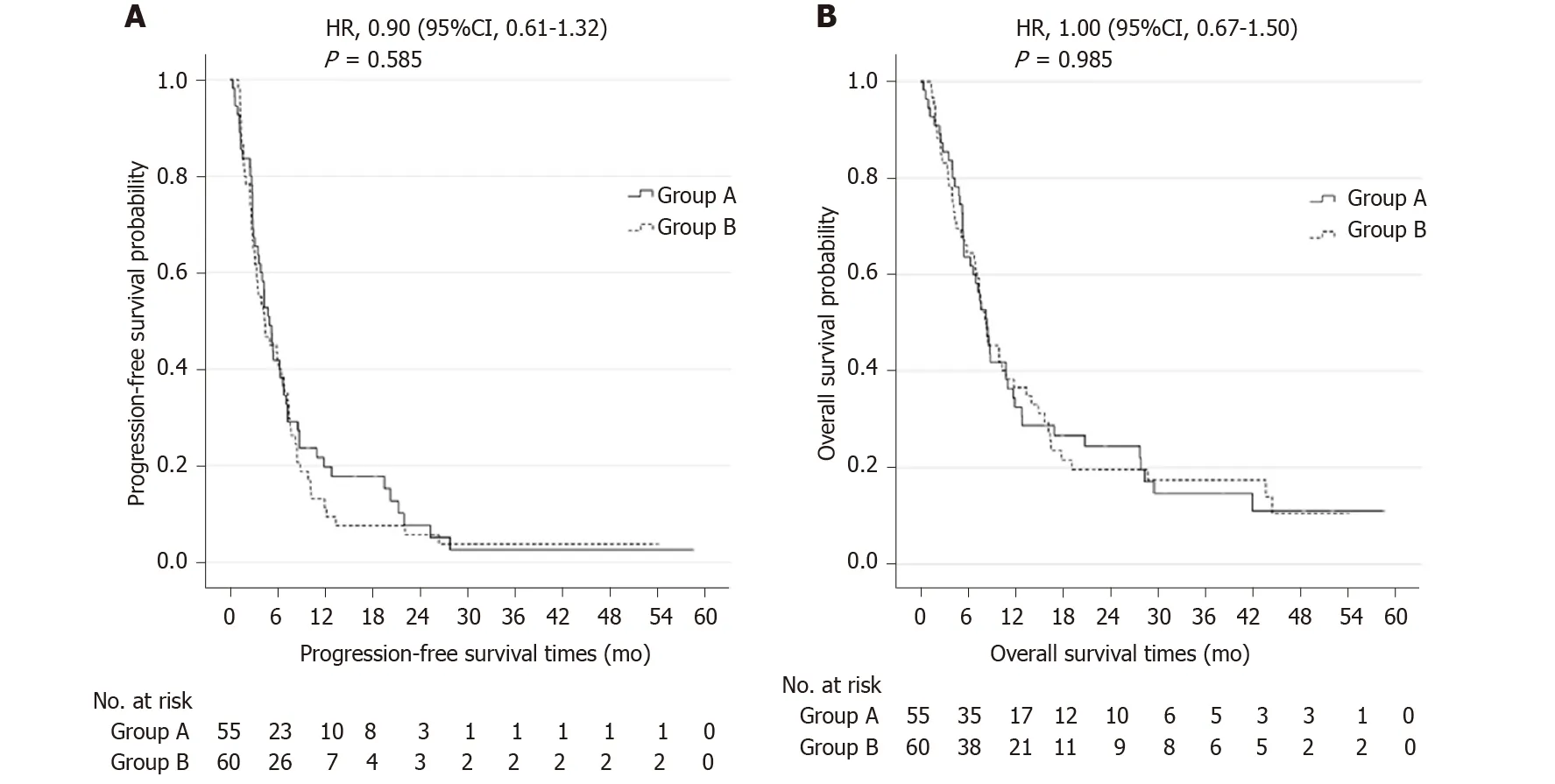

After a median follow-up period of 8.3 mo (0.4–58.6 mo), the median PFS for patients receiving TACE/HAIC + S-1 and TACE/HAIC was similar: 5.0 mo (0.4−58.6 mo; 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.82 to 6.18) and 4.4 mo (1.1−54.4 mo; 95%CI: 2.50 to 6.30) (P= 0.585) (Figure 2A). The median OS was also similar between the two groups: 8.4 mo (0.4−58.6 mo; 95%CI: 7.03 to 9.76) and 8.3 mo (1.4−54.4 mo; 95%CI: 6.00 to 10.60) (P= 0.985), respectively (Figure 2B). The PFS rates at 3, 6, 9 and 12 mo were 67.3%, 41.8%, 23.6% and 19.7%, respectively, in the TACE/HAIC + S-1 group and 65.0%, 41.7%, 18.7% and 11.2%, respectively, in the TACE/HAIC group. The OS rates at 3, 6, 9 and 12 mo were 85.5%, 63.6%, 41.8% and 32.5%, respectively, in the TACE/HAIC + S-1 group and 83.1%, 64.5%, 45.3% and 36.6%, respectively, in the TACE/HAIC group.

Follow-up

By the last follow-up, 20 patients were alive (9 patients in the TACE/HAIC + S-1 group and 11 patients in the TACE/HAIC group). In the TACE/HAIC + S-1 group, 3 patients received other treatments after progression, 3 patients were lost to follow-up, and 3 patients achieved a CR. In the TACE/HAIC group, 3 patients received sorafenib, 2 received other treatments after progression, 2 patients were lost to follow-up, 3patients achieved a CR and 1 patient achieved a PR.

Table 1 Summary of patient demographics and baseline disease characteristics, n (%)

Association between patient baseline factors and survival

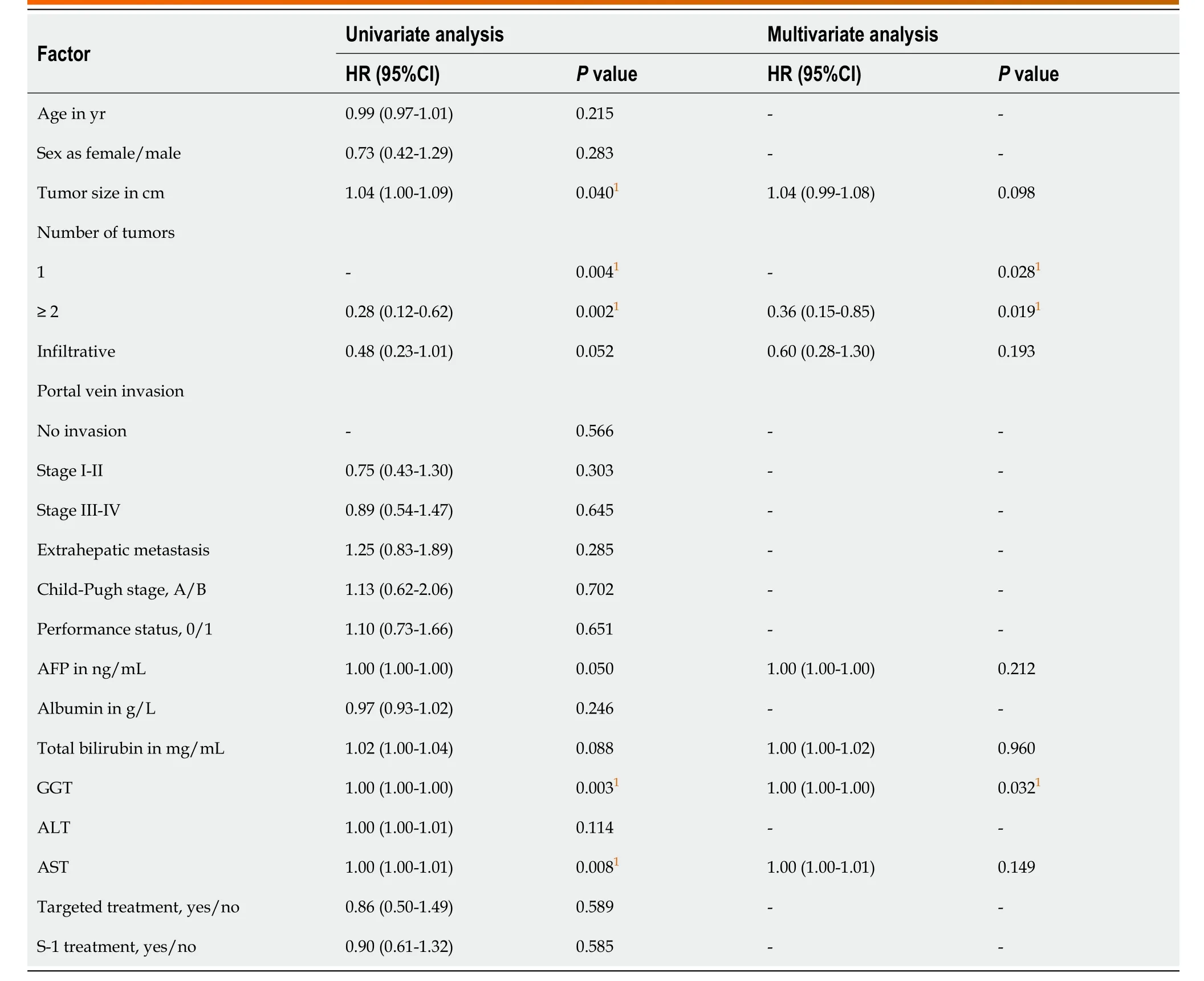

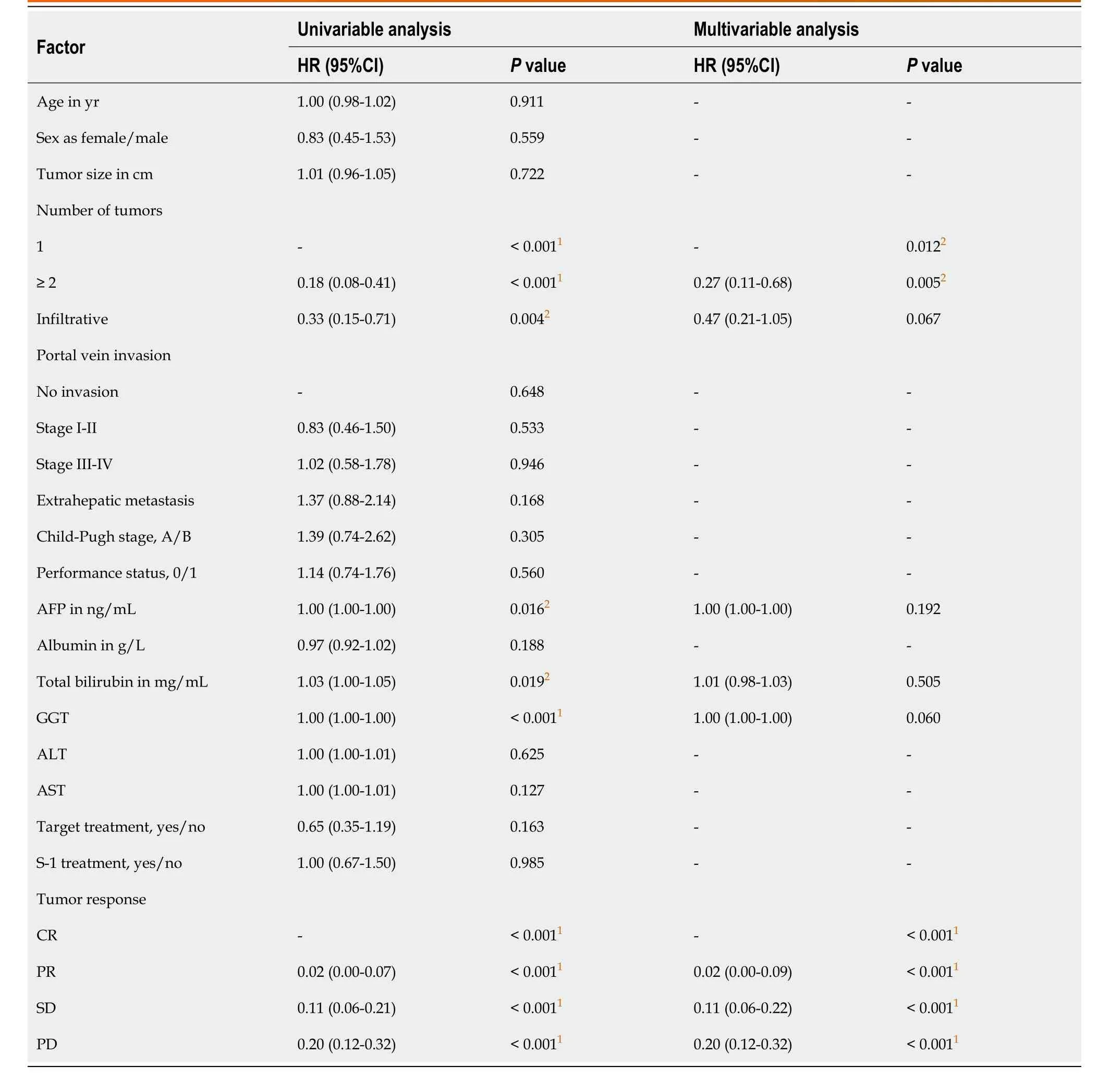

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses (Table 3 and Table 4) showed that the number of tumors and gamma-glutamyl transferase were predictive factors for PFS, and the number of tumors, gamma-glutamyl transferase and the tumorresponse were predictive factors for OS. However, age, sex, tumor size, portal vein invasion, extrahepatic metastasis, S-1 treatment and target treatment showed no significance as predictive factors.

Table 2 Response rates according to modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria, n (%)

Safety

In both treatment groups the most common AEs were transient liver injury (including elevation of serum liver enzymes and bilirubin), vomiting, abdominal nonspecific pain and fever (Table 5). Abdominal pain occurred frequently during HAIC and 2–3 d after TACE. This pain was adequately controlled by temporarily stopping the infusion of oxaliplatin or by the application of analgesics. Hematologic AEs observed included leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and anemia, and rates of theses AEs were also similar between the two treatment groups. One patient in the TACE/HAIC group experienced cerebral lipiodol embolism, however, they recovered after symptomatic treatment. The main AE related to S-1 was tolerable nausea. No incidences of neuropathy were observed in either group and no treatment-related death was observed.

DISCUSSION

The use of TACE combined with HAIC or systemic chemotherapy in patients with BCLC stage C HCC remains a controversial therapeutic approach. To the authors’ knowledge, the present study represents the first randomized, controlled trial of sequential TACE and HAIC plus oral S-1 in advanced HCC. Although the study did not meet its revised primary endpoint of PFS, a higher ORR and DCR were observed with the addition of S-1 to TACE/HAIC; 30.9%vs18.4% and 72.7%vs56.7%, respectively. The inability of the current study to detect a difference in survival may have been due to the poor prognosis of the patient population, who all had portal vein invasion or extrahepatic metastasis as mandated in the inclusion criteria. Additionally, our study suggests that both TACE/HAIC + S-1 and TACE/HAIC have acceptable safety profiles and are generally well tolerated by patients with advanced HCC.

In our study, treatment with TACE/HAIC + S-1 or TACE/HAIC led to an ORR of 30.9% and 18.4% and DCR of 72.7% and 56.7% and a median PFS of 5.0 and 4.4 mo, respectively. Compared with the findings of the present study, a previous phase II non-randomized controlled study showed higher rates of ORR (68.9%) and a longer median PFS (8.0 mo) for TACE/HAIC in patients with advanced HCC, although it should be mentioned that this study excluded patients with portal vein invasion or extrahepatic metastasis[21]. The large difference in response rates and PFS observed between our study and this previous study almost certainly reflects that the patient population in our study included those with portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic metastasis, for whom prognosis is usually extremely poor[15,30]. Additionally, the median OS in the present study was 8.4 mo and 8.3 mo for patients receiving TACE/HAIC + S-1 and TACE/HAIC, respectively. These results are broadly comparable if not slightly higher than the median OS reported from a combined subanalysis of the two Phase III trials of sorafenib in patients with advanced HCC with macrovascular invasion (n= 162; 184 d, approximately 6.1 mo) and extrahepaticmetastasis (n= 261; 223 d, approximately 7.4 mo)[30].

Table 3 Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for progression-free survival

Patients with BCLC Stage C HCC, with portal vein invasion or extrahepatic metastasis, were selected for this study because most other studies of HAIC have focused on patients with moderate-stage HCC and Child-Pugh class A liver function. At the time our study was initiated, sorafenib was the only recommended treatment for advanced HCC in most international guidelines. However, the ORR associated with sorafenib in advanced HCC with portal vein invasion or extrahepatic metastasis is relatively low (2%−3.3%)[10,11]. Sorafenib is also not easily accessible for many patients in China due to the relatively high cost of treatment. In addition, TACE alone also has limited efficacy in HCC with portal vein invasion[31,32]. Although liver cancer cells are relatively resistant to chemotherapeutic drugs, HAIC can provide significantly higher drug concentration ratios locally in tumor tissue compared with peripheral tissue and can promote a permanent antitumor immune response. The relatively higher survival observed in this studyvsprevious results with sorafenib in similar patient subpopulations may reflect that HAIC combined with TACE is more effective than HAIC or TACE alone. There are several factors supporting this hypothesis. Firstly, tumor cell hypoxia induced by TACE can enhance the antitumor effects of oxaliplatin. Secondly, the continuous hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin can kill residual cancer cells after TACE, especially those that remain active. Finally, S-1 provides the possibility of improving extrahepatic tumor control.

In addition to systemic therapies and HAIC, localized irradiation is also an alternative treatment for patients with advanced HCC characterized by vascular invasions. Selective internal radiotherapy with yttrium-90, or radioembolization,which is one of the intra-arterial treatments, can also be performed in patients with intermediate to advanced HCC[33]. However, selective internal radiotherapy is higher cost and unavailable in China. With the technical development of radiotherapy, stereotactic body radiation therapy can deliver high precision and intensity radiation to tumor tissue while sparing surrounding tissue. In a systematic review and metaanalysis including 2577 patients with unresectable HCC, subgroup analyses showed nonsignificant survival benefit in the TACE plus radiotherapy group compared with the TACE alone group for patients with portal vein tumor thrombosis[34]. In summary, further studies are necessary to evaluate localized irradiation value in the treatment of advanced HCC.

Table 4 Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses for overall survival

The major limitation of this study was that the primary endpoint had to be adjusted from TTP to PFS due to the high number of patients experiencing death from liver failure before disease progression. However, because TTP and PFS are closely related endpoints, we consider that the sample size calculation and study power would haveonly been marginally affected by this change in endpoint. Another limitation of this study was its open-label nature, which meant that subsequent treatments for patients who stopped study treatment may have been influenced by the investigator and patient decisions.

Table 5 Observed adverse events according to common terminology criteria for adverse events grading, n (%)

In conclusion, the addition of S-1 to sequential TACE and oxaliplatin-based HAIC did not lead to improved PFS or OS in patients with advanced HCC with portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic metastasis, although anti-tumor effect appeared to be greater with the addition of S-1. Both treatment regimens were similarly well tolerated by patients. Given that systemic therapy has only limited benefit for this patient population and is inaccessible for patients in many countries, and based on the promising results achieved with TACE and HAIC, identifying a strategy to derive the optimal benefit from these approaches remains an unmet need.

Figure 1 CONSORT flow diagram. TACE: Transarterial chemoembolization; HAIC: Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy.

Figure 2 Kaplan-Meier curves. A: Curves of progression-free survival; B: Curves of overall survival. Group A indicates hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy after transarterial chemoembolization plus S-1. Group B indicates hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy after transarterial chemoembolization. HR: Hazard ratio.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The prognosis for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) characterized by vascular tumor invasion and/or extrahepatic metastasis is almost always very poor. Systemic therapy with sorafenib was the only recommended firstline therapy for these patients at the beginning of this study. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is recommended for the treatment of patients with intermediate stage HCC, although it has been investigated in patients with more advanced disease with equivocal results. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) has shown promising local benefits for advanced HCC. S-1 has proven to be a convenient oral chemotherapeutic agent with definite efficacy against advanced HCC.

Research motivation

Sorafenib had shown limited benefit and was not easily accessible for many patients due to high cost. Other therapeutic approaches such as TACE and HAIC have been investigated in clinical practice, particularly in the Asia Pacific region. However, equivocal data mean that these approaches remain controversial in patients with advanced HCC. Novel treatment strategies are therefore being sought, and TACE followed by HAIC with oxaliplatin has shown promising preliminary results.

Research objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of treatment with TACE followed by oxaliplatinbased HAIC, with or without oral S-1, in advanced-stage HCC with portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic metastasis, we use progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint and overall survival (OS), objective response rate, disease control rate and safety as the secondary endpoints.

Research methods

In this single-center, open-label, randomized, controlled trial, patients with advanced HCC were randomized (1:1) to receive TACE (epirubicin 20-40 mg) followed by oxaliplatin-based HAIC (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2) either with (TACE/HAIC + S-1) or without (TACE/HAIC) oral S-1 60 mg twice daily.

Research results

Our results showed that the addition of oral S-1 to TACE followed by HAIC with oxaliplatin did not lengthen PFS and OS, although numerically higher objective response rate and disease control rate were observed for TACE/HAIC with S-1vswithout S-1 (30.9%vs18.4% and 72.7%vs56.7%). Both treatment regimens were similarly well tolerated by patients.

Research conclusions

In conclusion, TACE combined with HAIC was an effective and safe treatment for patients with advanced HCC with portal vein invasion and/or extrahepatic metastasis, although the addition of S-1 to sequential TACE and oxaliplatin-based HAIC did not lead to improved PFS or OS.

Research perspectives

Given that systemic therapy has only limited benefit and is inaccessible for patients with advanced HCC in many countries, and based on the promising results achieved with TACE and HAIC, identifying a strategy to derive the optimal benefit from these approaches remains an unmet need.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年27期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年27期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Histopathological landscape of rare oesophageal neoplasms

- Details determining the success in establishing a mouse orthotopic liver transplantation model

- Modified percutaneous transhepatic papillary balloon dilation for patients with refractory hepatolithiasis

- Serum ceruloplasmin can predict liver fibrosis in hepatitis B virusinfected patients

- Acceptance on colorectal cancer screening upper age limit in South Korea

- Intestinal NK/T cell lymphoma: A case report