Global woodland structure from local interactions:new nearest-neighbour functions for understanding the ontogenesis of global forest structure

Arne Pommerening,Hongxiang Wangand Zhonghua Zhao

Abstract

Keywords: Species segregation function, Size segregation function, Mingling-size hypothesis,Neighbourhood allometric coefficient, random labelling

Background

Many theories and hypotheses have been proposed to explain the maintenance of plant and tree diversity in forest ecosystems(Pommerening and Uria-Diez 2017).

The Janzen-Connell hypothesis (Janzen 1970; Connell 1971), for example, proposes that elevated numbers of specialist natural enemies, such as herbivores and pathogens, maintain diversity in plant communities. They reduce the survival rates of conspecific seeds and seedlings located close to reproductive adults or in areas of high conspecific density (Comita et al. 2014) leading to elevated conspecific self-thinning (Yao et al. 2016), i.e. a progressive decline in density in a population of growing individuals of the same species (Begon et al. 2006, p.157). An important effect of the Janzen-Connell hypothesis is the negative density/distance dependence that occurs when nearby conspecific plants negatively affect performance through mechanisms such as intraspecific competition and pest facilitation (Wills et al. 1997;Wright 2002; Piao et al. 2013;Yao et al. 2016).

Another important ecological hypothesis in this context, the herd immunity hypothesis, focuses on the variation in heterospecific neighbour densities and predicts that species diversity confers protection from natural enemies by making it more difficult for specialist natural enemies to locate host plants (Wills et al. 1997). Thus the spatial spread of an infection can be slowed down or even stopped by mixtures of susceptible and resistant species (Begon et al. 2006). Therefore individual plant fitness should be enhanced in stands involving many species but reduced in stands with low species diversity(Wills et al. 1997; Murphy et al. 2016).

In addition, Ford (1975) and Weiner and Solbrig(1984) demonstrated how the Janzen-Connell and the herd immunity hypotheses can affect natural populations. One observation in many natural plant populations is that self-thinning leads to size inequality (also referred to as local size hierarchies), where heterospecific stands include dominant plants emerging from a first colonisation cohort, which are often surrounded by patches of smaller sized plants of the same cohort.Small plants of these early colonisers are initially often of the same species as the dominant plants and according to the mechanisms of both the Janzen-Connell and herd immunity hypotheses later decrease in numbers due to self-thinning processes. Eventually the small early colonisers are partially or completely replaced by even smaller individuals of other species from subsequent colonisation cohorts. This combined effect of species and size replacement enforces both local size inequality and the mingling of different plant species in a given area or patch and prevents the development of monocultures (Pommerening and Grabarnik 2019).

Synthesising the key elements of the aforementioned ecological hypotheses, Pommerening and Uria-Diez(2017) and Wang et al. (2018) have concluded that - as a consequence of them - there is often a tendency for plants with high species mingling, i.e. those with heterospecific nearest neighbours, to be larger sized plants and referred to this as the mingling-size hypothesis.

Some aspects of these theories could be confirmed in experiments but many processes are still largely unknown. However, the effects described by the Janzen-Connell, herd-immunity, size inequality and minglingsize hypotheses are strictly local effects, i.e. their spatial range hardly exceeds 8-10 m in temperate and boreal forests. It is therefore interesting and important to study how the local woodland structures emerging from these localised effects cooperate in space and time and influence the global structure of a forest stand or woodland.Of particular interest is the question of how localised clusters of tree vegetation evolve in the vicinity of large parent trees, how these localised clusters interact and eventually merge to form overall global stand structure.This question has to be pursued using spatial approaches, since different spatial scales are involved. As typical local clusters of 1-2 mature trees surrounded by smaller offspring essentially constitute neighbourhoods,nearest-neighbour approaches seem most appropriate.These methods are part of point process statistics, one of the main fields of spatial statistics, and good overviews are offered in the textbooks by Illian et al. (2008),Wiegand and Moloney (2014) and Pommerening and Grabarnik(2019).

The objective of this paper is to show how recently proposed nearest-neighbour characteristics can contribute to tracing the ontogenesis of global forest stand structure from localised neighbourhoods and particularly how measures of species and size diversity are related.

Methods

Nearest-neighbour approaches of species and size diversity

Gadow (1993) and Aguirre et al. (2003) extended the species segregation index by Pielou (1977) to general multivariate species patterns involving k neighbours.The mingling index Mi(Eq. 1) is defined as the mean heterospecific fraction of plants among the k nearest neighbours of a given plant i. In the analysis, every plant within a given research plot acts once as plant i (Pommerening et al. 2019).

The mingling approach is particularly useful in woodlands with many species, because the only distinction made is between co- and heterospecific pairs of trees.

Expected mingling, EM, (implying independent species marks) as explained in Pommerening et al. (2019) and in analogy to Pielou’s segregation index, can now be used to normalise species mingling in such a way that the resulting measure Ψ is independent of the number of species and refers to the null hypothesis of independent species marks according to

Pommerening and Uria-Diez (2017) referred to the index defined in Eq. (2) as species segregation index.Here M is mean mingling of a tree population. Consequently, Ψ=0, if the species are independently or randomly dispersed. If the nearest neighbours and a given tree always share the same species, Ψ=1 (attraction of the same species leading to species segregation). Ψ=-1 is approached, when many neighbours are increasingly of a different species than the tree under consideration(attraction of different species).

Since the number k of nearest neighbours is related to different scales of local neighbourhood that can vary considerably within and between forest stands, Pommerening et al. (2019) considered a function Ψ(k) that depends on variable k (Eq. 3).

With increasing k, Ψ(k)→0. Our hypothesis is that the exact way in which Ψ(k) approaches 0 is a better quantitative description of the mingling pattern in a given population than M or Ψ alone. For plant patterns with completely random species dispersal (independent species marks) Ψ(k)=0 for all k (Pommerening et al.2019).

The interpretation of the function is straightforward and basically follows the interpretation of Ψ (Eq. 2).

An appropriate test involves the null hypothesis of a priori marking or random superposition, also referred to as population independence (Illian et al. 2008; Pommerening and Grabarnik 2019). This requires simulating n=2499 spatial patterns with independent marks for estimating global envelopes (Myllymäki and Mrkvička 2019). Since species is the mark of interest, spatial mark independence is simulated by random shifts of species populations (Illian et al. 2008, p. 460 f.; Pommerening and Grabarnik 2019, p. 182 f.). For this purpose we selected as many species as required to shift approximately half of all points in the observation window.In the simulations, all individuals of the selected species are shifted by adding the same random values zxand zyto the x and y coordinates of these individuals. A variant of periodic boundary conditions ensures that all points are inside the observation window.

Size differentiation is defined as the mean of the ratio of smaller and larger plant sizes u of the k nearest neighbours subtracted from one. In the analysis, every plant within a given research plot acts once as plant i (Gadow 1993).

Here u can be any quantifiable plant size measure.The value of Tiincreases with increasing average size difference between neighbouring trees. Ti=0 implies that neighbouring trees have equal size, whilst larger size differences approach an upper value of 1.

Pommerening and Uria-Diez (2017) referred to the index defined in Eq. (6) as size segregation index. Since the index takes the expectation into account, it is normalised for the range of sizes involved in each study population, which the original size differentiation index is not. Consequently, Υ=0, if plant sizes are independently dispersed without any spatial correlation of marks.If the sizes of the nearest neighbours and a given plant are more frequently of similar size than expected by chance, Υ ≈1 (attraction or aggregation of similar sizes leading to a segregation of sizes). Negative values tending towards -1 are achieved, if more neighbours have sizes quite different from that of a tree under study (attraction of different sizes; aggregation in the classical sense of Pielou’s original approach) than expected in a pattern of independently dispersed sizes (Wang et al.2020).

With increasing r, Υ′(r)→0, i.e. spatial independence of size marks is approached with distance used in the index calculation. The interpretation of Υ′(r) follows that of Υ. For plant patterns with spatially independent plant sizes, Υ′(r)=0 for all r (Wang et al. 2020).

As with any quantitative marks, the null hypothesis relates to a posteriori marking or random labelling. Simulations under this mark independence hypothesis are typically based on fixed point locations and permutated marks. According to the traditional random-labelling method, all size marks are freely permutated without restriction. However, when multivariate patterns involving several species are studied, it is common to restrict random labelling in such a way that plant sizes are only permutated within each species population (Wiegand and Moloney 2014, p. 227 f.; Wang et al. 2020). As a result the non-spatial empirical size distribution of each species are preserved.Also here we applied n=2499 simulations for estimating global envelopes (Myllymäki and Mrkvička 2019).

Our hypothesis is that the exact way in which Ψ′(r)and Υ′(r) approach 0, i.e. the morphology of Ψ′(r) and Υ′(r), and the two aforementioned random-labelling tests give vital clues about local pattern formation in forests.

Characterising the morphology of species and size segregation functions

Allometric relationship between species segregation and size inequality

yielding the same results as Eq. (10). For all calculations we have written our own code in R (version 3.5.1),C++ and additionally used the GET package (R Development Core Team 2019; Myllymäki and Mrkvička 2019).

Example data

To illustrate the new nearest-neighbour characteristics,the associated statistical tests and other curve characteristics, we selected four example forest sites from China.

Daqingshan forest region (abbreviated as D) forms a part of the Daqingshan Forest Farm of the Experimental Center of Tropical Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry. The research area is situated in Pingxiang City,Guangxi Province, which is close to the border between China and Vietnam. The native vegetation type is characterised by southern subtropical monsoon forests and evergreen broad-leaved forests involving diverse broadleaved species. Native species mainly include Quercus griffithii HOOK. f. & THOMSON ex MIQ., Erythrophleum fordii OLIVER, Castanopsis hystrix MIQ., Mytilaria laosensis LECOMTE, Betula alnoides BUCH.-HAM. EX D. DON and Dalbergia lanceolata ZIPP. EX SPAN. Plot Da (22°17′N, 106°42′ E) was established in 2018 and the prevailing main-canopy species are Cunninghamia lanceolata and Mytilaria laosensis LEC. and subdominant broadleaved species include Macaranga denticulata (BL.) MUELL.ARG., Schefflera octophylla (LOUR.) HARMS., Machilus chinensis (CHAMP. EX BENTH.) HEMSL., Castanopsis hystrix MIQ. and Liquidambar formosana HANCE.

Jiaohe forest region (abbreviated as J) is an experimental forest situated in the Dongdapo Nature Reserve(43°51′-44°05′N and 127°35′-127°51′E),Jilin Province,north-eastern China. The climate is largely influenced by monsoons from the Pacific Ocean and cold air from the interior Asian continent. The stand, denoted as Jb, is a mixed Fraxinus mandshurica-Juglans mandshurica forest. It mainly includes Fraxinus mandshurica RUPR.,Juglans mandshurica MAXIM., Acer mandshurica MAXIM., Carpinus cordata BL., Acer mono MAXIM. and Pinus koraiensis SIEB. ET ZUCC.

Jiulongshan Forest (abbreviated as JS) is located in the western suburbs of Beijing (39°57′ N and 116°05′ E) in the northern branch of Taihang Mountain. The climate in this region is temperate continental and largely influenced by monsoon conditions. The selected stand, JSa, is dominated by planted Platycladus orientalis (L.) FRANCO and is mixed with some naturally regenerated species such as Quercus variabilis BLUME, Broussonetia papyrifera (L.) VENT., Ailanthus altissima (MILL.) Swingle, Prunus davidiana CARR. and Gleditsia sinensis LAM.

Xiaolongshan Forest (abbreviated as XS) is part of the Xiaolongshan Nature Reserve, Gansu Province, northwest China. The forest is situated on the north-facing slopes of the West Qinling Mountain range (33°30′-34°49′ N and 104°22′-106°43′ E) and constitutes a natural mixed pine-oak forest. The research plot labelled as XSc represents a natural deciduous broad-leaved mixed forest and Quercus aliena var. acuteserrata MAXIM.,Dendrobenthamia japonica (DC.) FANG. var. chinensis and Acer davidii FRANCH. are the most abundant species.This forest stand was restored since the 1970s after commercial harvesting (Pommerening et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2020).

Results

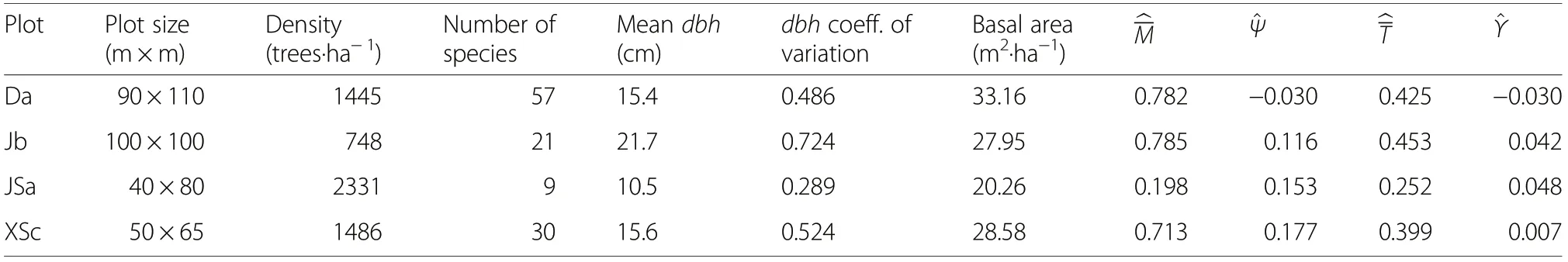

The four example research plots have tree densities that range from 748 tree per hectare (at Jiaohe, plot b) to 2331 tree per hectare (at Jiulongshan, plot a) and from 20.3 m2·ha-1(at Jiulongshan, plot a) to 33.2 m2·ha-1(at Daqingshan, plot a) (Table 1).

Table 1 Basic characteristics of the four example research plots. D - Daqingshan forest region, J- Jiaohe forest region, JS -Jiulongshan Forest, XS-Xiaolongshan Forest. , , and were calculated for k=4 neighbours

Table 1 Basic characteristics of the four example research plots. D - Daqingshan forest region, J- Jiaohe forest region, JS -Jiulongshan Forest, XS-Xiaolongshan Forest. , , and were calculated for k=4 neighbours

PlotPlot size(m×m)Density(trees·ha-1)Number of species Mean dbh(cm)dbh coeff.of variation Basal area(m2·ha-1)M^Ψ^^T^Υ Da90×11014455715.40.48633.160.782-0.0300.425-0.030 Jb100×1007482121.70.72427.950.7850.1160.4530.042 JSa40×802331910.50.28920.260.1980.1530.2520.048 XSc50×6514863015.60.52428.580.7130.1770.3990.007

Not only for testing the significance of the estimated characteristics but also for understanding the spatial relationship between species and size it is instructive to carry out the aforementioned two different types of random labelling tests: The first test is the “traditional” one(results in the left column of Fig.2), where the different species occurring in the research plots are ignored and all sizes are permuted regardless of species. An important consequence of this test is that the species-specific mark distributions change from simulation to simulation and can largely deviate from those observed in the original plot. The second variant of the test (results in the right column of Fig.2) is preferred by many quantitative ecologists and statisticians (Wiegand and Moloney 2014,p.227 f.).Here the permutations are restricted by species boundaries, i.e. tree sizes are permuted within species populations only. As a consequence species-specific mark distributions are preserved in the simulations, i.e.they are exactly the same in each simulation and correspond with those originally observed. However, for the less abundant species this can lead to situations where within the tiny species populations hardly any permutation of sizes is possible.

When comparing the envelopes in the left with those in right column of Fig.2 we clearly see that they are centred towards zero for the traditional test but not for the restricted random labelling test. In some cases the envelopes of the restricted test follow the observed curves more closely than those of the traditional test,e.g. for Daqingshan and Xiaolongshan Forests. In other cases, such as for Jiaohe and Jiulongshan, the differences in the envelopes of the two tests appear to be marginal.As a consequence, the strongly significant test outcome indicated by the traditional method when applied to Daqingshan turns out to be merely an artefact and the observed size segregation function is only marginally significant when the correct test procedure, i.e. the restricted random-labelling method, is applied. A similar situation exists at Xiaolongshan. However, the question why the test envelopes differ so markedly between the two test methods for some patterns but not for others remains and will be discussed in the next section, as it is rather important.

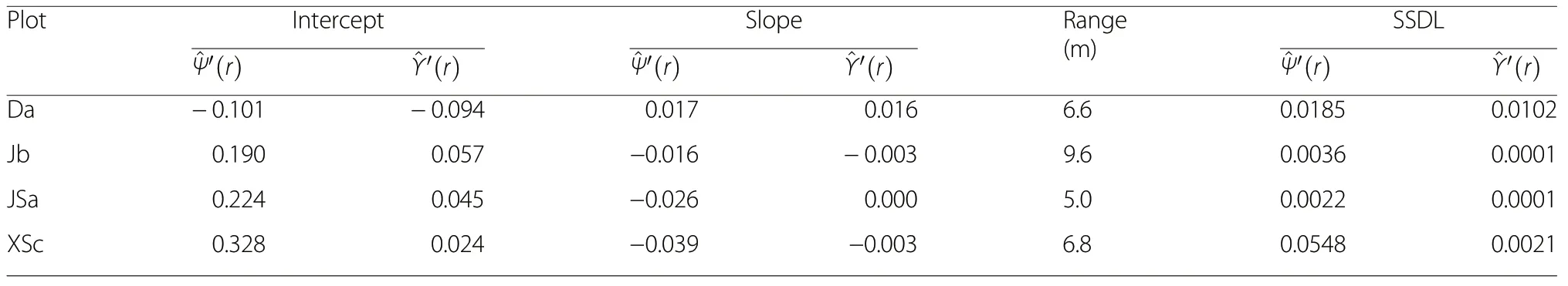

The morphology of the species and size segregation functions is of particular interest for making inference about processes of natural maintenance of tree diversity.Table 2 summarises four characteristics of morphology,intercept and slope from applying a linear regression model, the spatial range of the two segregation functions and SSDL, a measure of deviation from linearity.

Discussion and conclusions

Our analyses have clearly shown that the species and the size segregation functions are a very useful addition to existing point process characteristics, since they relate nearest-neighbour characteristics to spatial scales. There are only few existing characteristics in point process statistics that combine neighbourhood and spatial scales(Wiegand and Moloney 2014). Our new segregation functions are nearest-neighbour characteristics that depend on distance and thus give valuable insights on how mingling and size differentiation effects decrease with distance. This information is crucial for understanding how local forest structure evolves and eventually contributes to global forest structure. As part of this,morphology of the segregation functions correlation range and nonlinearity are of particular interest. Applying the new methods to the four example woodlands has demonstrated the extent of neighbourhood effects and that the decline of these effects largely differs between them. Of particular interest is also the correlation range of the two new functions, since it indicates the spatial extent of influence of local neighbourhood. From applying the two functions we have understood that local neighbourhoods in temperate woodlands in China, such as those that we studied, extend to 8-12 m.

Table 2 Shape characteristics of the estimated species segregation function and the size segregation function. Interceptfrom linear regression,expression of maximum size segregation; Slope- from linear regression,expression of how rapidly andtend towards a value of 0;Range-difference between average distance to first and 30th nearest neighbour, SSDL -sum of squares of deviation from linearity(Eq. 8)

Table 2 Shape characteristics of the estimated species segregation function and the size segregation function. Interceptfrom linear regression,expression of maximum size segregation; Slope- from linear regression,expression of how rapidly andtend towards a value of 0;Range-difference between average distance to first and 30th nearest neighbour, SSDL -sum of squares of deviation from linearity(Eq. 8)

?PlotInterceptSlopeRange(m)SSDL^Ψ′(r)^Υ′(r)^Ψ′(r)^Υ′(r)^Ψ′(r)^Υ′(r)Da-0.101-0.0940.0170.0166.60.01850.0102 Jb0.1900.057-0.016-0.0039.60.00360.0001 JSa0.2240.045-0.0260.0005.00.00220.0001 XSc0.3280.024-0.039-0.0036.80.05480.0021

The two random labelling test methods applied in Fig.2 revealed another important aspect of size-species relationships: While the restricted random labelling method,which takes the existence of distinct species populations into account, is undoubtedly the better option for testing spatial mark independence, there were two sites, Jiaohe(plot b) and Jiulongshan (plot a) where the choice of test procedure mattered little. This begs the important question why some forest patterns are sensitive to the random labelling test method and others are not. In situations, where the envelopes greatly differ between tests, the non-spatial size-mark distributions greatly differ between the most abundant species (Fig.4). This in turn affects spatial size differentiation where local neighbourhoods include several different species, i.e.where attraction of different species is high.

Apparently this is the situation in Daqingshan (plot a).In this plot, unrestricted size permutations across species boundaries produce spatial size differentiation among nearest neighbours that does not match observed size differentiation,hence the envelopes of traditional random labelling are markedly different from the observed curves.Thus the strong effect of quite different sizes at close proximity at Daqingshan is mainly a consequence of species with different size-mark distributions mingling at this range.By contrast,the three other forest sites show a conspecific attraction,i.e.here the within-species size variability is more important than the between-species differences in size range, particularly at Xiaolongshan (plot c). However, at Jiaohe (plot b) and Jiulongshan (plot a) also the size distributions of the most abundant species are quite similar(see Fig.4)which contributes to an outcome where spatial size differentiation in unrestricted random labelling is quite similar to that produced by restricted random labelling. Figure 4 confirms this explanation, except that in the case of our four example plots the size-mark distributions of the two most abundant species appear to be the most influential ones.

Thus the comparison between the two randomlabelling test methods offers vital insights on how species and size segregation are related in mixed-species forests. It tells a particularly interesting story about the interaction between local and global forest structure that otherwise would not have emerged, if only the seemingly“correct” test were applied.

Acknowledgements

H.W. gratefully acknowledges a grant from the IUFRO-EFI Young Scientists Initiative that provided him with the opportunity to work three months at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences at Umeå(Sweden)in 2019.We thank Mari Myllymäki (LUKE, Finland) for interesting discussions about the random-labelling test results.

Authors’ contributions

All authors equally contributed to all aspects of this work.

Funding

H.W. was partly supported by the Guangxi Innovation Driven Development Project (No. AA17204087-8). Z.Z.was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project No. 31670640).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets and programming code used for current study are available from the authors on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author details

1Faculty of Forest Sciences, Department of Forest Ecology and Management,Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences SLU, Skogsmarksgränd 17, SE-901 83 Umeå,Sweden.2College of Forestry, Guangxi University, Nanning 530004,China.3Key Laboratory of Tree Breeding and Cultivation of National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Research Institute of Forestry, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Box 1958,Beijing 100091, China.

Received: 20 November 2019 Accepted: 26 February 2020

- Forest Ecosystems的其它文章

- Benefits of past inventory data as prior information for the current inventory

- Trade-offs between wood production and forest grouse habitats in two regions with distinctive landscapes

- Innovative deep learning artificial intelligence applications for predicting relationships between individual tree height and diameter at breast height

- Wild bee distribution near forested landscapes is dependent on successional state

- Gap models across micro-to mega-scales of time and space:examples of Tansley’s ecosystem concept

- Variation of net primary productivity and its drivers in China’s forests during 2000-2018