A case of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage following synthetic cathinone inhalation

Masakazu Nitta, Taro Tamakawa, Natsuo Kamimura, Tadayuki Honda, Hiroshi Endoh

Advanced Emergency and Critical Care Center, Niigata University Medical and Dental Hospital, Chuo-ku, Niigata, Japan

Dear editor,

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) sometimes causes a life-threatening condition; thus, prompt diagnosis and treatment for DAH is crucial. However, a variety of diseases (e.g., systemic autoimmune diseases, infectious diseases, drugs) are associated with the development of DAH, which occasionally causes diffi culty with identifying the specifi c etiology.[1]

Synthetic cathinones (SCs) have gained popularity as a recreational drug since 2012 in Japan, and SC intoxication sometimes results in organ dysfunction.[2,3]However cases of DAH following SC intoxication have not previously been reported.[2-6]

We here present a 28-year-old man in hypoxic respiratory failure due to DAH. Although tests failed to identify the underlying cause of DAH, he recovered spontaneously and was discharged without any complications. About 2 months later, he was brought to our hospital again with mild DAH. According to the pharmacological aspect of SCs, which he confessed to inhale, we finally elucidated that the cause for DAH could be SC intoxication.

CASE

A 28-year-old man was found lying unconscious at home and brought to our emergency department (ED) by ambulance. Two months earlier, he was admitted to the hospital because of loss of consciousness and aspiration pneumonia. He had a previous psychiatric history of depression but no history of drug abuse. His medications included paroxetine, brotizolam, etizolam, and lormetazepam. His family history was unremarkable.

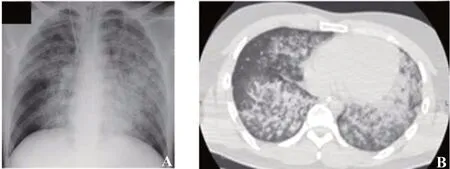

Upon arrival to our ED, he had a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 4, and his vital signs were as follows: BP 117/37 mmHg, HR 118/minute, RR 14/minute, SpO273% on a non-rebreather mask, and temperature 35.0 °C. He was intubated and underwent a lung computed tomography (CT) scan, which revealed diffuse and bilateral ground glass opacities (Figure 1A, B). His initial arterial blood gas analysis on ventilator (FiO21.0, PEEP 14 cmH2O) showed a pH 7.18, PCO273 mmHg, PO2113 mmHg, HCO3-26.8 mmol/L, and lactate 4.5 mmol/L. Laboratory values (laboratory reference range) on arrival were as follows: white blood cell count 16,070/μL (3,590-9,640/μL), hemoglobin 16.8 g/dL (13.2-17.2 g/dL), platelets 37.6×104/μL ([14.8-33.9]×104/μL), sodium 146 mEq/L (138-146 mEq/L), potassium 4.6 mEq/L (3.6-4.9 mEq/L), chloride 102 mEq/L (99-109 mEq/L), creatinine 2.2 mg/dL (0.6-1.1 mg/dL), aspartate aminotransferase 46 U/L (13-33 U/L), alanine aminotransferase 30 U/L (8-42 U/L), creatine kinase 1,143 U/L (62-287 U/L), C-reactive protein 0.1 mg/dL (<0.3 mg/dL), B-type natriuretic peptide 21.1 pg/mL (<18.4 pg/mL), activated partial thromboplastin time 33.1 seconds (26.9-40.9 seconds), prothrombin time 85% (81.0%-131.6%), fi brinogen 335 mg/dL (160-400 mg/dL), fibrin degradation products 13.4 μg/mL (<5 μg/mL), and D-dimer 7.2 μg/mL (<1.0 μg/mL). An autoimmune workup was negative for antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (PR3, MPO), anti-DNA antibody, and anti-Sm antibody. An infective workup was also negative for any cultures, beta-D-glucan, and platelia aspergillus. Drug testing of his urine (Triage®DOA, Biosite Diagnostics Inc., USA) qualitatively detected the presence of a benzodiazepine. Bronchoalveolar lavage showed hemorrhagic effluent. Cytology of this fl uid showed numerous red blood cells without bacterial, mycobacterial, and fungal cultures. Serial hemoglobin measurements revealed a progressive decline from 16.8 g/dL in the ED to 13.4 g/dL the next day. These results are consistent with DAH.

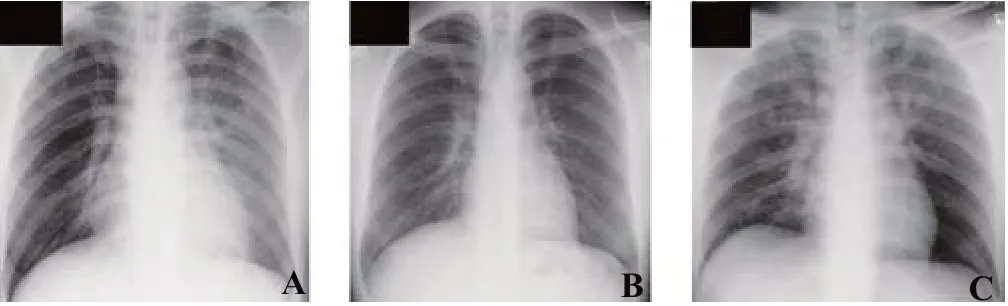

He was admitted to the intensive care unit and ventilated for 4 days. Although the cause of DAH was not identified, hypoxemia was ameliorated without adjunctive therapy such as corticosteroids (Figure 2A). He was discharged on hospital day 7. A follow-up X-ray taken at an outpatient clinic was normal (Figure 2B).

About 2 months after discharge, he was brought to our ED again with unconsciousness. His chest X-ray showed recurrence of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates that was less serious than before (Figure 2C), and he was admitted to the emergency ward. On hospital day 2, his consciousness normalized, and he confessed that he had inhaled a recreational drug, which was purchased locally in a small independent store, before his hospitalization. He mentioned that the drug name was ”BON'S CRYSTAL”, but he did not possess the rest of it at that time. He was discharged without clinical sequelae on hospital day 2.

Later, it was reported by the health welfare department of the prefecture that the drug contained alpha-ethylaminopentiophenone and 4-fluoro-alphapyrrolidinovalerophenone (PVP), known as SCs.

DISCUSSION

Figure 1. A chest X-ray (A) and a chest CT scan (B) on arrival. Both of them revealed diffuse and bilateral ground glass opacities.

Figure 2. The follow-up chest X-rays on hospital day 5 (A), at an outpatient clinic on day 16 (B), and on the day of re-admission (C). C: it showed recurrence of bilateral pulmonary infi ltrates that was less serious than his fi rst hospitalization.

The course of this patient suggested two important clinical issues. First, SCs as recreational drugs may cause DAH. SCs have gained popularity as recreational drugs since 2012 in Japan,[2,3]and neurological/psychiatric findings (e.g., agitation, loss of consciousness, and seizure-like activity) and sympathomimetic physical findings (e.g., tachycardia, hypertension, and hyperthermia) were frequently reported as the clinical features of SC intoxication. These features are in keeping with the known pharmacological effects of SCs as a potent dopamine/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. However, to our knowledge, there is no previously reported human case of DAH due to SC intoxication.[2-6]On the other hand, there are some case reports showing that poisoning with illicit drugs (e.g., amphetamine and cocaine) resulted in DAH.[7,8]The SCs that were inhaled by this case are phenylalkylamine derivatives producing an amphetamine-like effect; therefore, it is reasonable that SC intoxication can cause DAH.[9]

Second, because illicit drug poisonings are difficult to diagnose unless the patients confess them, appropriate treatments can be delayed such as with this case. Legislations have been passed in Japan in the past decade to ban the use of some SCs.[10]Hence, we can easily imagine that people who take such drugs tend to disguise their use to avoid being caught by the police. Recently, there has been a worldwide rise in the abuse of recreational drugs, and the number of patients intoxicated with them is increasing. Therefore, we should be aware of the possibility of intoxication for any patient.

This report has a major limitation. We did not analyze any samples from the patient in terms of SCs because poisoning was not suspected and samples were not stored after both admissions. So we could not confi rm that the cause of DAH was SC inhalation. However, from the clinical course, we believe that DAH due to SC inhalation was the most likely diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

We report a case of DAH following SC inhalation. The patient was hospitalized twice for DAH, and we did not consider that the cause of DAH could be SC inhalation until his confession. For patients suffering from DAH of unknown origin, the possibility of illicit drug intoxication like SC should be considered.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that there are no confl icts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Contributors:MN proposed and wrote the fi rst draft. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts.

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Availability of basic life support courses for the general populations in India, Nigeria and the United Kingdom: An internet-based analysis

- The importance of visualization of appendix on abdominal ultrasound for the diagnosis of appendicitis in children: A quality assessment review

- Clinical characteristics and prognosis of communityacquired pneumonia in autoimmune diseaseinduced immunocompromised host: A retrospective observational study

- The life-saving emergency thoracic endovascular aorta repair management on suspected aortoesophageal foreign body injury

- Effects of intracoronary injection of nicorandil and tirof ban on myocardial perfusion and short-term prognosis in elderly patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after emergency PCI

- Morbidity and mortality risk factors in emergency department patients with Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia