Morbidity and mortality risk factors in emergency department patients with Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia

Rui-xue Sun, Priscilla Song, Joseph Walline, He Wang, Ying-chun Xu, Hua-dong Zhu, Xue-zhong Yu, Jun Xu

1 Emergency Department, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing 100010, China

2 Department of Anthropology, Washington University in Saint Louis, Saint Louis 63101, USA

3 Division of Emergency Medicine, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis 63101, USA

4 Laboratory Department, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China

KEY WORDS: Acinetobacter baumannii; Bacteremia; Morbidity; Mortality

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii (AB) is a gramnegative, aerobic bacterium, which belongs to the family Neisseriaceae.[1]It is an opportunistic pathogen in humans that can be found in environmental soil and water samples, on human skin, as well as inside respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.[2]Recently, AB has gained global notoriety as a nosocomial pathogen capable of causing serious infections including bacteremia, soft tissue infections, meningitis, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections.[3]What’s more, AB is resistant to most available antibiotics, limiting treatment options, and leading to patients with infections caused by AB to have a high mortality rate approximately 10%–43% in intensive care units (ICUs) and 7.8%–23% outside of ICUs.[4,5]Among such infections, AB bacteremia is associated with especially high mortality rates ranging from 29% to 63%.[6-8]Several studies have investigated risk factors for morbidity and mortality in patients with AB bacteremia.[3,4,7]However, none of these studies focused on emergency department (ED) patients in China.

In recent years, emergency medicine in China has witnessed rapid development. The Chinese ED physicians are tasked not only with triaging and stabilizing patients, but also with determining patients’ final diagnoses and treating patients in many cases over weeks and even months. For example, the ED in our institution consists of nine consulting rooms for ambulatory patients, 20 beds in a resuscitation area, 30 beds in an observation area, 25 beds in a comprehensive ward and 10 beds in an emergency ICU (EICU). The ED receives many patients in critical condition and treats them independently of other services. As our ED has had many patients with AB bacteremia recently, we aimed to find out the morbidity and mortality risk factors of AB bacteremia in ED patients.

METHODS

Study population and data collection

Adult patients (>18 years old) were enrolled in a 1:1 matched retrospective case-control study performed in the ED of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) in Beijing, China. Patients with clinical signs of infection and confirmed with AB bacteremia were the case group. Patients without AB infection were selected randomly and served as the control group. The time period assessed for inclusion was from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2015. The patients in case group and control group were matched for primary diagnosis, gender, age (± fi ve years) and length of stay.

A standardized form was designed to collect data on the following factors: age, gender, hospitalization time, primary diagnosis, underlying diseases, central venous catheter presence, ventilator requirements, exposure to antibiotic therapies, and immunosuppression. For patients with AB bacteremia, further data were also collected, including co-infection with other pathogens in the bloodstream, antibiotic susceptibilities, appropriate antimicrobial therapy and patients’ outcomes. Based on the outcomes, the case group was divided into a mortality group and a survival group.

Def nitions

Patients were deemed as hospitalized in our ED when the length of stay exceeded 24 hours in either the resuscitation area, observation area, comprehensive ward or EICU. AB bacteremia was defined at the time when AB was isolated from one or more blood samples. Exposure to corticosteroids or antibiotic therapy was defi ned as corticosteroids or antibiotics given during the hospital stay before the first blood sample that revealed AB. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy was defined as having at least one antibiotic which was proven sensitive on in-vitro analysis administered via an approved dosage, duration and route within 48 hours after the onset of bacteremia. Patients’ outcomes were assessed at the time of discharge from the ED. Hospitalization time was the time from admission to discharge from the hospital. Patients with CVCs had double-lumen central venous catheters.

Microbiological analysis

Blood cultures were incubated in a BacT/ALERT 3D system and were identified using the VITEK identification system. Antimicrobial susceptibility profiles were determined by the Kirby Bauer Disc Diffusion Method. The data were analyzed using the 2012 breakpoint following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommendations.[9]

Statistical analysis

Risk factor associations for AB bacteremia morbidity and mortality for patients infected with AB bacteremia were analyzed by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. To identify independent risk factors, parameters with P<0.05 in the uni-variate analysis were analyzed using a multivariate logistic regression model. P<0.05 was considered as statistically signifi cant. SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

Between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2015, 816 patients were hospitalized in our ED, and 51 (6.25%) of these patients were identified with AB bacteremia. Totally 35 (68.60%) patients with AB bacteremia died. In the case group and control group, the mean age was 58.3±18.4 years old and 53.6±19.0 years old, respectively. The male to female ratio was 1.32:1. The average length of hospitalization time was 15.96±13.78 days in the case group and 7.40±8.83 days in the control group. The most common primary diagnosis was a pulmonary infection, which was present in 51.0% (26/51) and 41.2% (21/51), respectively. The most common underlying chronic comorbidities were diabetes mellitus 19.6% (10/51) in the case group and cancer 17.6% (9/51) in the control group. There was no signifi cant difference in age or sex between the case and control groups. All patients were administered with antibiotics based on their clinical situation and pathogen susceptibility results.

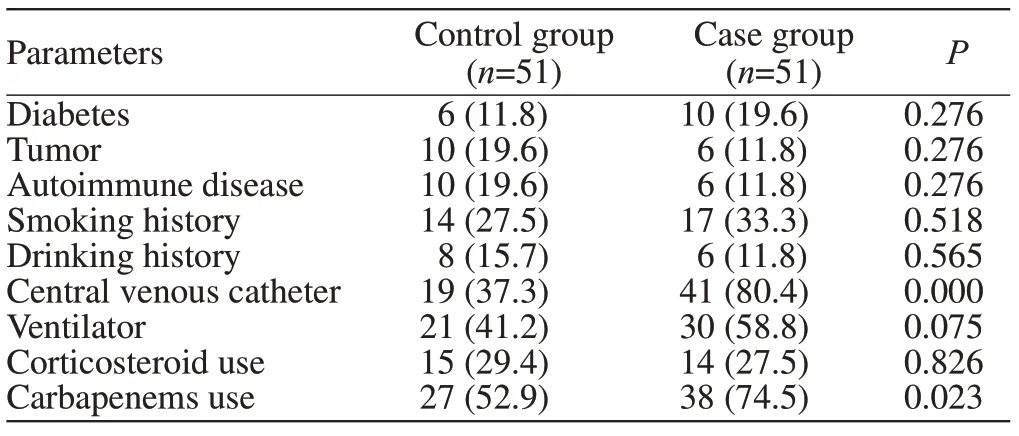

Risk factors for AB bacteremia morbidity are shown in Table 1. Uni-variate analysis indicated two risk factors associated with morbidity: exposure to carbapenem antibiotics (P=0.023), and the presence of a central venous catheter prior to AB pathogen identification (P<0.001) (Table 1). A logistic regression analysis revealed that the presence of a central venous catheter was independently associated with morbidity (P<0.001, OR=9.961, 95% CI=2.817–35.218).

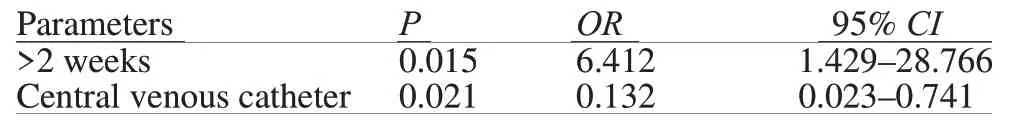

When examining mortality, the central venous catheter and the hospitalization time longer than two weeks were both associated with mortality in patients infected with AB bacteremia in a uni-variate analysis (Table 2) (P=0.007) as well as in a multivariate analysis (P=0.015) (Table 3).

Table 1. Risk factors for morbidity of AB bacteremia by uni-variate analysis, n (%)

Table 2. Risk factors for mortality of AB bacteremia by uni-variate analysis, n (%)

Table 3. Risk factors for mortality of AB bacteremia by multivariate analysis

DISCUSSION

Bacteremia caused by AB has become a common nosocomial infection in critically ill patients,[9]but studies of AB bacteremia in ED patients are still lacking. As the ED plays an increasingly important role in many hospitals in China, including caring patients over 24 hours, it is now a common practice to develop a final diagnosis and treatment plan for critically ill patients, independent of other medical specialties. Because of this, nosocomial infections (such as AB bacteremia) can be acquired in the ED and require timely diagnosis, treatment and prevention strategies.

This study assessed risk factors for morbidity and mortality in patients with AB bacteremia. The factors found to be significant were hospitalization time longer than two weeks and CVC insertion prior to AB diagnosis for mortality and just CVC insertion for morbidity. Other studies examining AB morbidity and mortality in non-ED patients have reported multiple independent risk factors including age, ICU stay, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, WBC count, albumin level, antibiotic drug resistance profile, underlying malignant disease, organ failure, septic shock, pneumonia, previous use of ceftriaxone, mechanical ventilation, concurrent infection and appropriate antimicrobial therapy.[3,4,10-17]Our study was the first to identify the length of stay in the ED and CVC use as independent risk factors for mortality in ED patients.

CVC-related bacteremia is reduced through the following methods. (1) Hand hygiene and aseptic techniques which include using sterile gloves, surgical gowns, surgical masks, and a large sterile drape during CVC insertion as well as regular dressing changes being the most important and easy means for preventing CVC-related infections.[18](2) Choosing appropriate sites for CVC insertion (catheter-related infections are more common with femoral insertion sites compared to internal jugular or subclavian vein insertion sites).[19,20](3) Duration of catheterization is also an important risk factor for CVC-related infections. Although the risk of infection has been reported to increase after six days,[21]there is no defined time period recommended for replacing CVC catheters, and changing catheters has its own risks and costs. As a result, routine changing of catheters is controversial. Besides that, catheter and site care can also minimize the incidence of CVCrelated infection by using gauze rather than transparent dressings and cleaning the points of catheter access before accessing the system.[22,23]What’s more, several studies have shown that the use of antimicrobialimpregnated catheters reduce the incidence of CVCrelated infections,[24-26]although meta-analyses of these studies did find several methodological flaws. These kinds of antimicrobial-impregnated catheters also carry risks of anaphylactic allergic reactions and promoting the emergence of resistant organisms, so the overall effi cacy of antimicrobial-impregnated catheters remains uncertain.[24]

Although we found that hospitalization time longer than two weeks was an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with AB bacteremia, in our study the patients in the mortality group had much shorter hospitalization time than those in the survival group. The main reason was the poor prognosis of patients with AB bacteremia. All patients in our study were infected by carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) and several died at a relatively short time after ED admission. Therefore, early recognition and appropriate treatment of such cases are important. Blood cultures should be obtained before initiating antimicrobial therapy for any patients suspected of bacteremia, including hospitalized patients and outpatients with a fever.[27]Before receiving the bacterial susceptibility test results from blood cultures, patients presenting with signs of bacteria should be treated based on the local condition of nosocomial infections. In hospitals with known CRAB cases, critical care patients should be covered empirically.

There are some limitations to our present study. First, this study was performed in a single institution, potentially limiting the generalizability of our results to other hospitals. This was a retrospective investigation with a relatively small number of patients. We used mortality as the endpoint for this study, but patients in this study had multiple underlying diseases that may have contributed to their mortality besides AB bacteremia. We were also unable to obtain enough data from our included patients to calculate APACHE II scores, which was reported as a mortality risk factor in several other studies. Finally, this study was conducted in a clinical department, focusing on clinical outcomes and data. Acinetobacter contains 33 genomic species which are genotypically closely related and phenotypically difficult to distinguish, and we were unable to identify Acinetobacter isolates down to the species level. Molecular studies investigating AB genotypes and resistance mechanisms may be next targets for future studies.

CONCLUSION

In this study, the prognosis of patients with AB bacteremia was poor, and the presence of a central venous catheter is associated with higher morbidity and mortality in our department. Avoiding CVC-related infections in the ED may improve outcomes in patients with AB bacteremia.

Funding:This study was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2016-12M-1-003).

Ethics approval:The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Peking Union Medical College Hospital has approved this study.

Conflicts of interest:The authors declare that they have no confl icts of interest.

Contributors:RXS designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the fi nal version.

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Availability of basic life support courses for the general populations in India, Nigeria and the United Kingdom: An internet-based analysis

- The importance of visualization of appendix on abdominal ultrasound for the diagnosis of appendicitis in children: A quality assessment review

- Clinical characteristics and prognosis of communityacquired pneumonia in autoimmune diseaseinduced immunocompromised host: A retrospective observational study

- The life-saving emergency thoracic endovascular aorta repair management on suspected aortoesophageal foreign body injury

- Effects of intracoronary injection of nicorandil and tirof ban on myocardial perfusion and short-term prognosis in elderly patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after emergency PCI

- Prognostic value of intracranial pressure monitoring for the management of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage following minimally invasive surgery