Effects of intracoronary injection of nicorandil and tirof ban on myocardial perfusion and short-term prognosis in elderly patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after emergency PCI

Guo-xiong Chen, Hong-na Wang, Jin-lin Zou, Xiao-xu Yuan

Department of Cardiology, Zhoushan Hospital of Zhejiang Province, Zhoushan 316000, China

KEY WORDS: Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction; Elderly; Emergency coronary intervention; Nicorandil; Tirof ban; Myocardial reperfusion

INTRODUCTION

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is usually caused by a sudden decrease or cutoff of blood fl ow in one or more coronary arteries, leading to the injury or death of associated cardiac muscle. AMI has a prevalence of three million cases annually worldwide, with approximately one million deaths in the United States.[1]Clinical manifestations of AMI may be presented in three categories: unstable angina, non-STsegment elevation MI (NSTEMI) and ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI).[2]While STEMI is less frequent than NSTEMI in elder patients, the prevalence of STEMI in elderly patients has increased over recent years due to expansion of the ageing population worldwide.[3]Compared with younger STEMI patients, older STEMI patients have higher mortality, higher morbidity, and poorer prognosis.[4-6]The elderly STEMI population is underrepresented in the clinical literature because most studies on AMI do not include elderly individuals in their patient populations.[7]The keys to AMI treatment are the rapid opening of infarction relative artery (IRA), the early restoration of blood fl ow to the injured myocardial tissue, subsequent decreases in infarct size, the rescue of dying myocardium, and improved patient prognosis.[8,9]Emergency percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the mainstay of treatment for STEMI patients, including elderly patients.[9]PCI effectively reduces mortality and the rate of recurrence in patients with myocardial infarction.[10]However, PCIinduced recanalization of submembranous blood vessels does not guarantee the complete recovery of tissue-level reperfusion. The presence of no reflow phenomenon (NRP) occurs when the ischemic myocardial tissue does not receive appropriate perfusion despite reopening of the occluded coronary arteries. This condition signifi cantly compromises the effi cacy of PCI treatment and patient prognosis.[8,11]Elderly STEMI patients are prone to NRP and other complications such as bleeding events associated with PCI.[5,12]Additional management and emergency PCI to reduce the incidence of NRP and other complications in elderly STEMI patients are necessary to improve treatment effi cacy and prognosis.

In recent years, elderly STEMI patients have been treated effectively after PCI with either tirofi ban, a nonpeptide antagonist of the platelet glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa receptor and an inhibitor of platelet aggregation,[13]or nicorandil, a vasodilator.[14]The early use of tirofi ban significantly improves myocardial perfusion after PCI,[15,16]and nicorandil has been shown to substantially diminish infarct size in STEMI patients undergoing PCI.[17,18]However, few studies have been performed to investigate the effects of combined treatment with both drugs when administered as an intracoronary injection to elderly STEMI patients.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of the intracoronary injection of combined treatment with nicorandil and tirofiban on myocardial reperfusion and short-term prognosis in elderly STEMI patients undergoing emergency PCI.

METHODS

Patient selection and data collection

A total of 78 elderly STEMI patients (71 males and 7 females, age 65-88 [72.7±10.2] years old) who had been admitted to Zhoushan Hospital of Zhejiang Province between May 2017 and October 2019 for emergency PCI were selected for this study. In each case, the diagnosis of STEMI was made in line with the STEMI diagnostic criteria.[9]All patients had indications for emergency PCI. Patients who had all of the following were included in this study: (1) sustained chest pain for more than 30 minutes within 12 hours of disease onset; (2) ST-segment elevation greater than 0.1 mV on at least two adjacent leads on the ECG; (3) infarct-related arterial myocardial infarction thrombolysis test (TIMI) grade 0 to 1, or TIMI grade 2 to 3 with a clearly seen thrombus shadow in echocardiography.

Patients who had one of the followings were excluded from this study: (1) thrombolytic therapy within 1 week before surgery; (2) treatment with platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor blockers such as tirofiban within 2 weeks before surgery; (3) history of cerebral hemorrhage or history of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) within 6 months; (4) severe hepatorenal dysfunction; (5) history of active bleeding or hemorrhage; (6) history of thrombocytopenia or decreased preoperative platelets counts; (7) intracranial malignant tumors (primary or metastatic) or cerebrovascular structural abnormalities (such as arteriovenous malformations); and (8) recent major surgery or history of severe physical trauma. After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 78 patients were enrolled and divided into two groups (n=39 per group) by the random number method: a control group, in which patients were treated only with tirofi ban, and an treatment group, in which patients were treated with both nicorandil and tirofiban, during and after emergency PCI.

The demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of each patient were collected from the hospital database and through outpatient follow-up.

Treatments

All patients routinely received aspirin (300 mg, Bayer Healthcare Co., Ltd.) and clopidogrel (polyvivi, 600 mg, Sanofi Hangzhou Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) or ticagrelor (Belinda, 180 mg, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals Limited) before surgery. Nitrate or statin was administered as necessary. Heparin (70-100 U/kg) was intravenously injected during the PCI procedure. In the control group, tirofi ban (10 μg/kg) was injected into the coronary artery when the guide-wire passed through the lesion, immediately after balloon pre-expansion (Lunan Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd.). Sixty seconds after injection, balloon dilation or stent placement was performed. Subsequently, tirofiban was intravenously infused and maintained at 0.1 μg/(kg·minute) until 36 hours after surgery. In the treatment group, patients received intracoronary injections with a loading dose (0.06 mg/kg) of nicorandil (Beijing Sihuan Kebao Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) during the PCI procedure. The injection was completed within 3 minutes, at which point the balloon was expanded or a stent was placed. Subsequently, tirofi ban and nicorandil were intravenously infused (0.1 μg/[kg·minute] and 2 mg/hour, respectively); levels were maintained for 36 hours after surgery. Unfractionated heparin (100 U/kg) was given intraoperatively. If NRP persisted in patients of either group after ruling out mechanical obstruction (e.g., subintimal tear, dissection, spasms, thromboembolism) the highest dose of tirofiban (25 μg/kg) or multiple doses of nicorandil (up to 24 mg) were administered. Additionally, verapamil or sodium nitroprusside was administered as an intracoronary injection to maximally eliminate NRP during the PCI operation. Postoperatively, patients routinely received the following treatments: (1) dual antiplatelet drugs, i.e., aspirin enteric-coated tablets 100 mg/day, clopidogrel 75 mg/day, or ticagrelor 180 mg/day; and (2) low-molecular-weight heparin, statins, ACEI, and/or beta-blockers. This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital, and all patients signed their informed consent.

Treatment indicators

The following treatment indicators were used in this study: (1) number of IRA without reflow, which was used to calculate the incidence of NRP;[9](2) coronary blood fl ow perfusion level: coronary TIMI grade before and after PCI, TIMI fl ow frame count (TFC) or corrected TIMI flow frame count (cTFC), and TIMI myocardial perfusion classification (TMPG);[9,10](3) resolution STsegment elevation (STR) 2 hours after PCI; (4) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular diastolic diameter (LVEDD) 5-7 days after PCI; (5) peak CK-MB levels 24-72 hours after PCI; (6) major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in-hospital and 30 days after discharge, including death, non-fatal re-infarction, revascularization of target blood vessels, frequent angina pectoris, exacerbated cardiac dysfunction (increased cardiac function grade with the Killip classification), postoperative hypotension; and (7) incidence of inhospital bleeding events. Patients were followed up after discharge via telephone inquiries.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 software. Measurement data that conformed to the normal distribution are expressed as mean±standard deviation. The independent samples t-test was used for comparison of data between groups, and the f or q test was used for multi-group data comparison. Count data were expressed as frequency or percentage (%). The χ2test was used for comparing data between groups. P <0.05 was considered statistically signifi cant.

RESULTS

Comparison of demographic and baseline clinical characteristics between control and treatment groups

A total of 78 elderly STEMI patients undergoing PCI were consecutively enrolled at our hospital during the period from May 2017 to October 2019. There were no signifi cant differences between the control and treatment groups in the distribution of risk factors for coronary heart disease such as gender, age, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (all P>0.05, Table 1).

Comparison of peak CK-MB level, IRA, STR and MACEs between control and treatment groups

Compared with the control group, the treatment group had signifi cantly lower peak levels of CK-MB and a lower incidence of IRA after PCI (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively; Table 2). All patients were reexamined by electrocardiography (ECG) 2 hours after surgery. The results showed that STR was significantly higher in the treatment group, compared with the control group (89.74% vs. 61.53%) (P<0.05). In addition, the treatment group had a significantly lower incidence of MACEs than the control group (P<0.05). The incidence of individual MACEs, such as cardiogenic shock, cardiac insufficiency, and death in both groups is presented in Table 3.

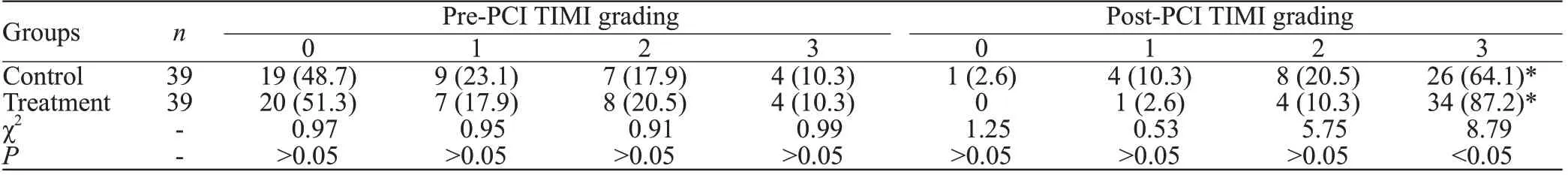

Comparison of TIMI grade before and after emergency PCI

Before the emergency PCI, there was no significant difference in TIMI grades between groups (P>0.05, Table 4). However, after PCI, 87.2% of patients in the treatment group had a TIMI grade of 3, compared with only 64.1% in the control group (P<0.05). Thus, the combined use of nicorandil and tirofiban significantly improved cardiac reperfusion, compared with the use of nicorandil alone.

Comparison of TMPG classif cation before and after emergency PCI

Before the emergency PCI treatment, there was no significant difference in TMPG classification between the control and treatment groups (P>0.05, Table 5).

Table 2. Comparison of postoperative peak CK-MB level, IRA-NRP, and incidence rates of STR and MACEs between control and treatment groups

Table 3. Comparison of MACEs between groups after PCI, n (%)

Table 4. Between-group comparison of TIMI grade before and after emergency PCI, n (%)

Table 5. Comparison of TMPG grade between groups before and after emergency PCI, n (%)

Table 6. Comparison of cTFC between control and treatment groups before and after intracoronary drug administration

Table 7. Comparison of echocardiographic parameters and bleeding events between control and treatment groups

However, after PCI, 89.7% of patients in the treatment group had a TMPG grade of 3, compared with only 78.1% in the control group (P<0.05).

Comparison of cTFC before and after intracoronary drug administration

As shown in Table 6, there was no significant difference in cTFC between the control and treatment groups before drug administration (P>0.05). However, the treatment group had a signifi cantly lower cTFC than the control group after drug administration (P<0.05).

Comparison of echocardiographic parameters and bleeding events

As shown in Table 7, there were no significant differences between the control and treatment groups in the incidence of thrombocytopenia or bleeding events (P>0.05). However, the treatment group had signifi cantly lower LVED and higher LVEF than the control group (P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the effects of combined treatment with nicorandil and tirofiban on myocardial perfusion and short-term prognosis in elderly STEMI patients after emergency PCI. The results showed that: (1) after PCI, more patients in the treatment group had TIMI 3 and TMPG 3, and STR was significantly higher compared with patients in the control group; (2) compared with patients in the control group, patients in the treatment group had signifi cantly lower cTFC, lower incidence of NRP, and lower peak CK-MB levels; (3) compared with the control group, the treatment group had signifi cantly lower LVEDD and higher LVEF at 7-10 days after surgery; (4) compared with the control group, the treatment group had signifi cantly lower incidence of MACEs <30 days post-operatively. Our fi ndings suggest that the intra-coronary injection of nicorandil and tirofi ban is effective for the treatment of elderly STEMI patients undergoing emergency PCI.

One complication associated with PCI is NRP. Risk for NRP is increased among patients older than 60 years of age with hyperglycemia, prolonged onset of emergency reperfusion, pre-infarction angina pectoris, and/or cardiogenic shock. Elderly AMI patients have a longer period of myocardial ischemia and more delays in treatment, leading to increased risk for NRP.[5,6,19]Although the underlying mechanisms of NRP are not completely understood, it is widely believed that PCIinduced injury to the structural integrity of the coronary microcirculation and subsequent microembolization are thought to be contributing.[20]The activation and aggregation of platelets are important factors, because the activation and aggregation of platelets contribute to the formation of microthrombi, which block the microcirculation.[21]Vascular endothelial damage and microvascular spasm may also contribute to the development of NRP.[22-24]Currently, there are no effective methods for NRP treatment. Hence, preventive methods, including shortening the total duration of myocardial ischemia, are of the utmost importance. In recent years, intracoronary drugs including anisodamine, sodium nitroprusside, calcium antagonists, uracil, glycoprotein Ⅱb/Ⅲa receptor antagonists, and nicorandil[18,22,25]have been used for the prevention and treatment of NRP during emergency PCI.[11,16,22]Tirofiban is a novel platelet membrane glycoprotein Ⅱb/Ⅲa receptor antagonist. Nicorandil is a new type of drug thought to have positive effects on myocardial microcirculation and myocardial blood perfusion in patients with AMI.[17,18,23]Previous studies have shown that combined treatment with two or more drugs via the coronary artery restores myocardium blood flow faster and more effectively than conventional treatment, with greater success in eliminating NRP.[22,25]In line with these reports, we found in this study that combined treatment with nicorandil and tirofiban, compared with the use of tirofiban alone, significantly reduced the incidence of NRP in elderly STEMI patients. Given that tirofi ban is an inhibitor of platelet aggregation and that nicorandil is a vasodilator, we speculated that the combined use of these two drugs synergistically reduced risk for NRP through these two mechanisms in elderly patients.

In this study, the treatment group had significantly less grade 0-2 TIMI and significantly less cTFC during emergency PCI, compared with the control group. The proportions of patients with TIMI 3 and TMPG 3 were signifi cantly increased in the treatment group, compared with the control group. Since TIMI grade reflects epicardial blood flow and cTFC and TMPG grades are indicators of coronary microvascular blood flow, these fi ndings indicate that combined treatment with nicorandil and tirofiban, compared with single-drug treatment, offered synergistic benefi ts in terms of myocardial tissue perfusion. At 2 hours postoperatively, the treatment group had significantly higher STR and lower peak values of CK-MB, compared with the control group, further supporting the notion that combined treatment with nicorandil and tirofi ban synergistically ameliorated ischemia-reperfusion-linked myocardial injury.

In the present study, we found that patients in the treatment group had significantly higher LVEF than patients in the control group, and significantly lower LVEDD than patients in the control group. In combination with the findings that the treatment group had significantly lower incidence of MACEs (either inhospital or during the 30-day follow-up period), our results indicate that the combined use of nicorandil and tirofiban synergistically improved left ventricular remodeling, improving short-term outcomes in elderly patients after emergency PCI. The mechanisms underpinning this improvement in cardiac function likely reflect synergistic benefits of the combination of nicorandil and tirofi ban, which improved coronary blood flow and myocardial perfusion. Alternatively, these changes may be associated with the pharmacological mechanisms of nicorandil described previously.[22,26]

It was previously reported that tirofiban may be associated with increased risk for bleeding in elderly vs. younger patients.[27]However, in the present study, we did not observe any significant difference in the incidence of bleeding events between the control and treatment groups, indicating that combined treatment with nicorandil and tirofiban via intra-coronary infusion was safe and did not increase the incidence of bleeding complications. Patients in the treatment group did experience minor bleeding events, such as skin ecchymosis and bleeding gums. These findings are consistent with previous reports.[22,26]Notably, combined intracoronary treatment with these two drugs did not result in complications such as thrombocytopenia, hypotension, or bradycardia.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. For example, this was a single institutional study. Also, we had a limited sample size. The findings from this study therefore need to be further corroborated in a large cohort and multi-institutional studies.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we report here that the intra-coronary injection of nicorandil and tirofi ban effectively decreases peak levels of CK-MB, reduces the incidence of NRP, improves cardiac function, and decreases MACEs in elderly STEMI patients undergoing emergency PCI. The findings described above support the view that the combined use of nicorandil and tirofiban is safe and should be recommended for the treatment of elderly STEMI patients undergoing emergency PCI.

Funding:Zhejiang Science and Technology Department (LGF20H020001), Zhoushan Science and Technology Bureau (2016C31040).

Ethical approval:This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital.

Conflicts of interest:The authors have no financial or other confl icts of interest regarding this article.

Contributors:GXC drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the fi nal manuscript.

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

World journal of emergency medicine2020年3期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Availability of basic life support courses for the general populations in India, Nigeria and the United Kingdom: An internet-based analysis

- The importance of visualization of appendix on abdominal ultrasound for the diagnosis of appendicitis in children: A quality assessment review

- Clinical characteristics and prognosis of communityacquired pneumonia in autoimmune diseaseinduced immunocompromised host: A retrospective observational study

- The life-saving emergency thoracic endovascular aorta repair management on suspected aortoesophageal foreign body injury

- Morbidity and mortality risk factors in emergency department patients with Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia

- Prognostic value of intracranial pressure monitoring for the management of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage following minimally invasive surgery