A Minimalist Account of Wh-Movement in Fulfulde

Bashir Usman & Baba-Kura Alkali Gazali

University of Maiduguri, Nigeria

Abstract Operator movement is one of the scholastic views which have been advanced to analyse expressions that contain an operator of some kind. In this work, attention will be focused on interrogative operator in Fulfulde. This work examines the nature of wh-movement in Fulfulde using the minimalist programme. In conducting the research, primary and secondary sources of data collection were employed. The native speaker’s intuition forms the primary source of data while the secondary source involves three competent native speakers of Adamawa Fulfulde to validate the data. The outcome of the study reveals four types of wh-movement in Fulfulde. The four types of wh-movement in Fulfulde are the subject preposed from its canonical position in declarative sentences to a new position in interrogative sentences. There are both left to right movement and right to left movement. The interrogative questions are marked by an optional ‘na’ at the end of the sentence. It is possible and grammatical to have double interrogatives but only one of the elements can move. The movement is determined by proximity, short or long movement of the interrogative marker to either left to right or right to left. However, wh- or interrogative element in Fulfulde is represented by -ye and -e suffixes bound to stems of pronouns and some prepositions. Pied-piping and preposition stranding are also observed. In some whmovement, the question remains in place called wh-in-situ; here, the interrogative marker does not move at all. When this happens the interrogative marker occupies the position of the element in question. When there is movement, each move element leaves behind a trace marked by ‘t’ and the trace is co-indexed so that we can see the extraction sites and the landing sites of the elements that have moved. The direct object preposed to the complementizer position through wh-movement and the subject of the main clause raises and moves into the subject position of the relative clause in order to check the question feature of comp in Fulfulde.

Keywords: wh-movement, minimalist, Fulfulde, interpretable and uninterpretable features, complementizer

Introduction

Fulfulde is one of the most widely spoken languages of Nigeria in particular, and West Africa in general. It is classified under West-Atlantic group of the Niger-Congo phylum (Greenberg, 1963). It has six major dialects. In Nigeria alone three main dialects have been identified which are mutually intelligible: Sokoto dialect, Northern Central Nigerian dialect, and Adamawa dialect (Arnott, 1970).

Constituent Structure of Fulfulde Sentences

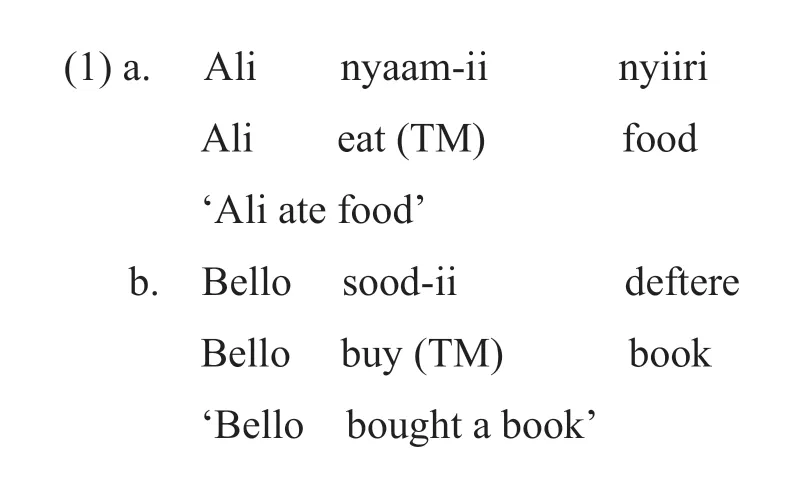

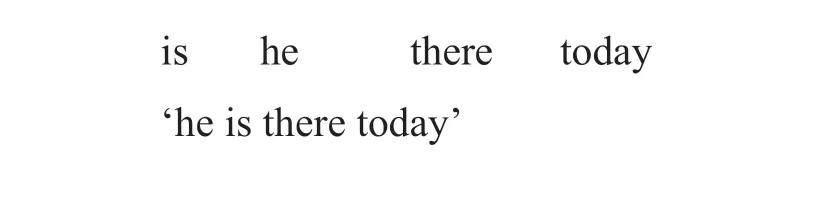

Noun phrases and verb phrases constitute Fulfulde sentences. Nouns and pronouns are the head of the NP; any other constituent that comes under the NP is optional; these include modifiers as well as specifiers. Fulfulde maintains its basic and permissible word-order thr oughout its grammar of declarative sentences. The basic word-order is S.V.O (subject-verb-object) as illustrated below:

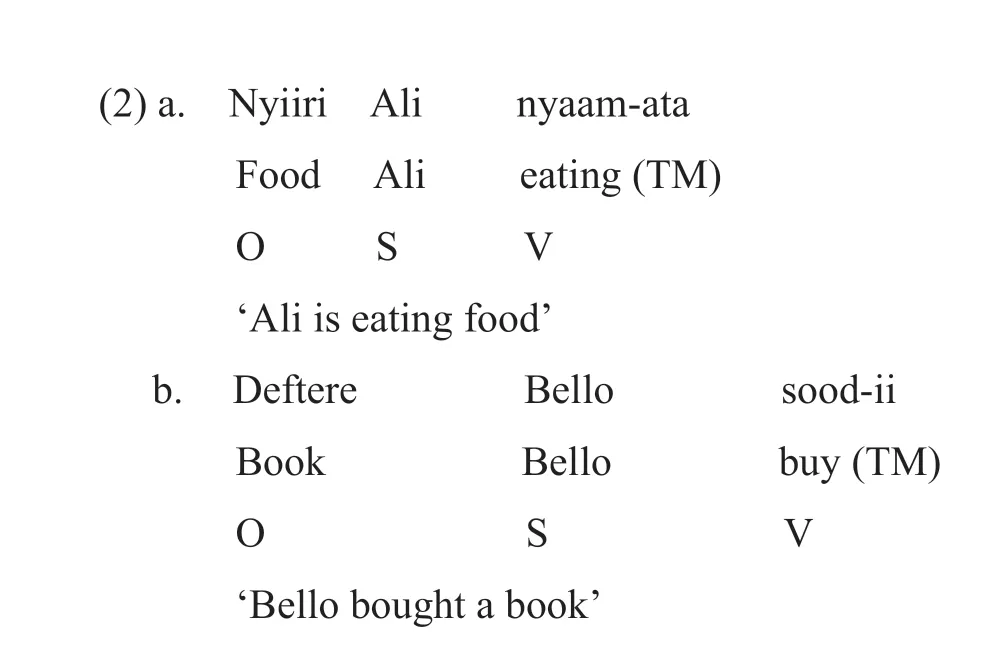

But the only possible variant of this basic word-ordering is O.S.V (objectsubject-verb) as illustrated below:

The above examples show that the basic and permissible word-order in main declarative sentences in Fulfulde. The verbs are in fixed final position and all the constituents occur before the verbs.

Arnott (1970, p. 26) and McIntosh (1984, p. 53) identify verbal and nonverbal sentences in Fulfulde. The verbal sentences which have a verbal form as a nucleus of the sentence can either be neutral or emphatic sentences, while the non-verbal sentence has no nucleus and is of five different forms depending on the elements that constitute these sentences. It comprises the subject and complement which form the obligatory constituent or part of the verb.

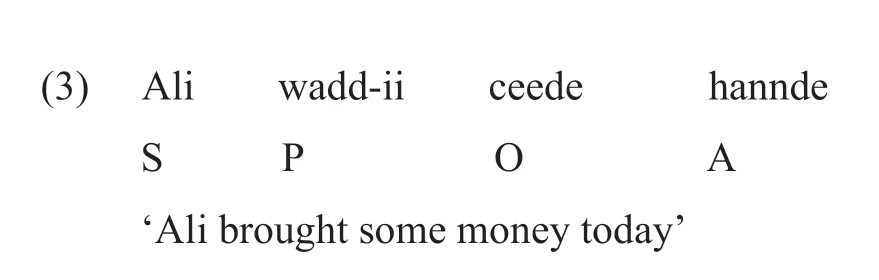

However, the basic structure of Fulfulde sentences is described in terms of subject (S), predicate (P), object (O), complement (C), and adjunct (A) (Arnott, 1970 in Daudu, 2005). The exponent of subject, object and complement in whatever type of sentence they occur is a nominal group or an adverbial group. The subject and object element can function as subject and object in some non-verbal sentences. The exponent of predicator in verbal sentences is a verb, while in non-verbal sentences there are a small number of quasi-verbal forms and stabilizing elements. As for the exponent of adjunct for both verbal and non-verbal sentences, it is normally an adverbial group (Arnott op.cit. in Daudu op. cit.). Consider the following examples:

In the above example, Ali is the subject, wadd-ii is the predicate, ceede is the object, and hannde is adjunct, which is an adverb.

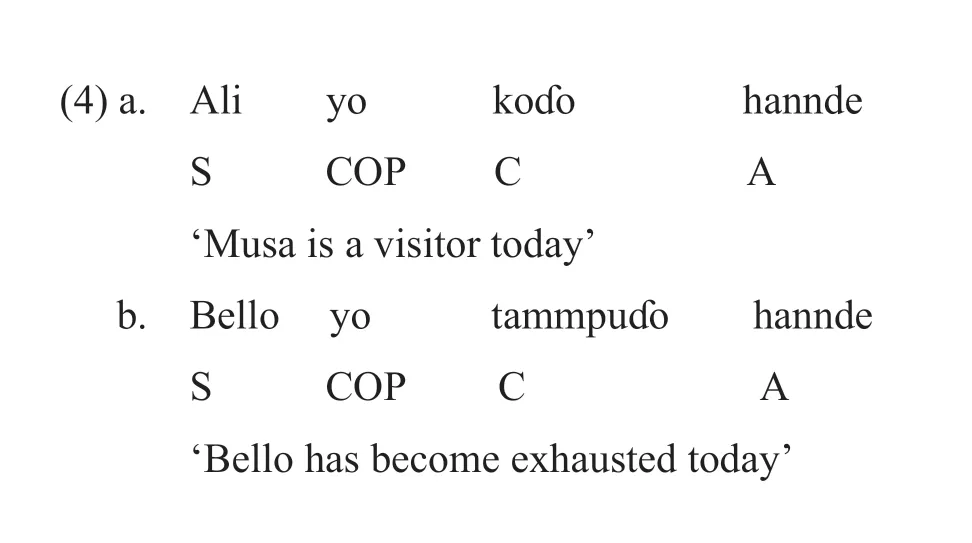

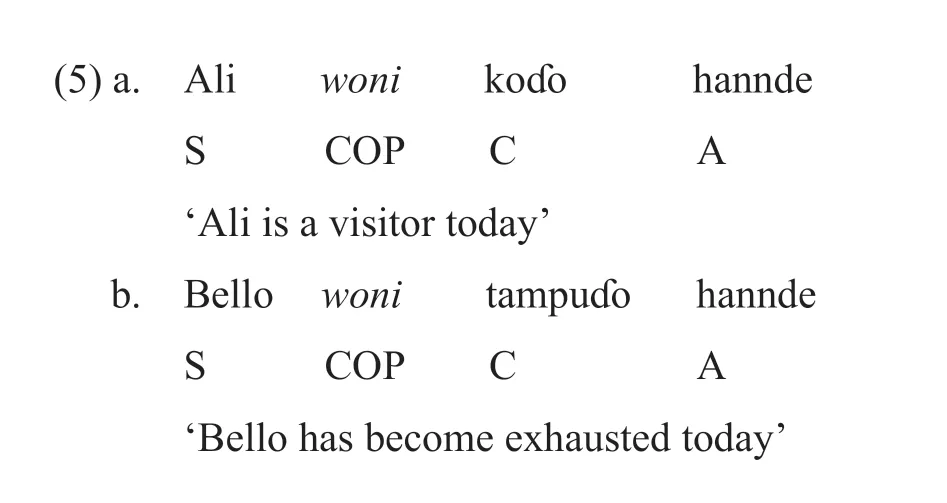

For the non-verbal sentences, Arnott (1970) identifies five different forms depending on the elements that make up each sentence. Essentially, a subject and a complement constitute the first type of the non-verbal sentences. A complement serves as any obligatory element or constituent part of the verb and a copula may be obligatory if there is an adjunct following the internal argument. Consider the following examples:

From the above examples, the copula may be optional as in Kaceccereere dialect; it is a subject of the quasi-verb, and it must appear for the sentence to be grammatical, whereas in Adamawa Fulfulde the copula may not be ‘yo’, rather ‘woni’. Consider the following examples:

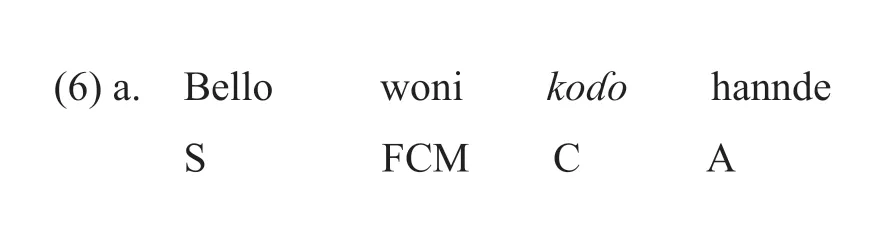

From the above examples, the copula remains optional. Here, Daudu (2005) argues that ‘woni’ is used in emphatic sentences as a focus marker which is sensitive to number. Let us consider the following examples:

From the above examples, the initial consonant of the copula becomes altered to /ng/ because it is preceded by a plural subject, unlike in (6a) which has a singular subject.

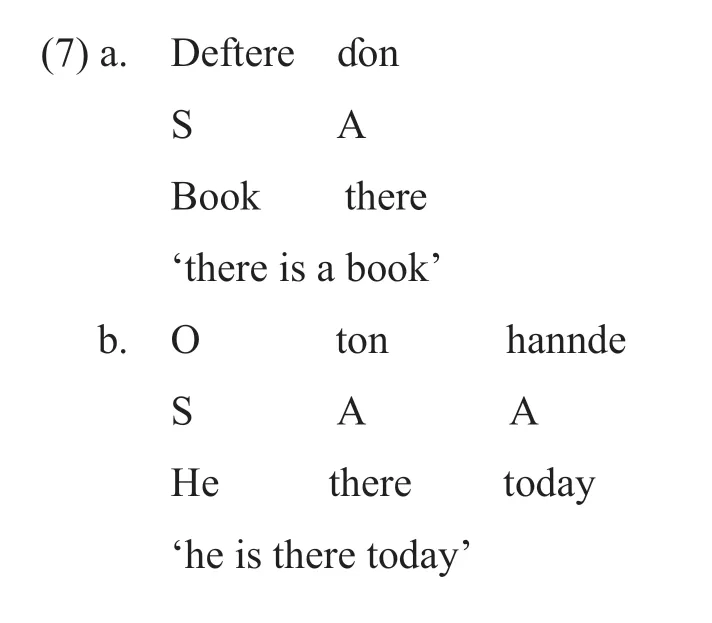

The second type of the non-verbal sentence is the one that has a subject and a verb with one or more optional adjuncts essentially. Here, Daudu (2005) argues against Arnott’s (1970, p. 32) presentation on what he refers to as a stabilizing element ‘xon’ as a predicator. Consider the following examples:

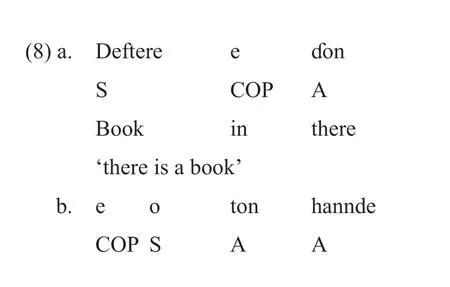

In the above examples, ‘ɗon’ is an existential element as against Arnott (1970), who refers to it as a stabilizing element (a predicator) or adjunct. He argues that in some dialects like the Kaceccereere, the copula ‘e’ has to be placed between S and A if the subject is a noun, but, if it is a pronoun, the copula moves to the initial position, and thus:

In the above examples, the subject in (8b) is followed by what Daudu (2005) describes as existential element, which Arnott (1970) refers to as an adjunct (predicator) and the sentence has two adjuncts; the subject becomes ‘mo’ as an internal argument because it does not begin a sentence, rather a complement of ‘e’.

The third type of non-verbal sentence is those that have adjunct and subject with no other adjunct. The initial adjunct can be an interrogative adverbial (no means ‘how/how many’, and to means ‘how’). Let us consider the following examples:

In the above sentences, the subject constitutes the nominal group which very often occurs as a genitival complex, and then the following adjunct constitutes the adverbial group.

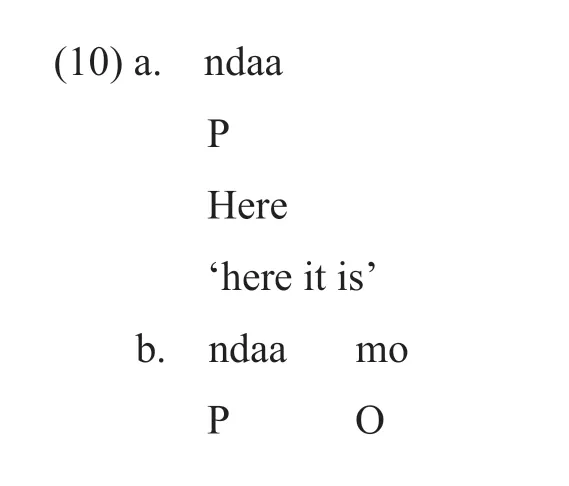

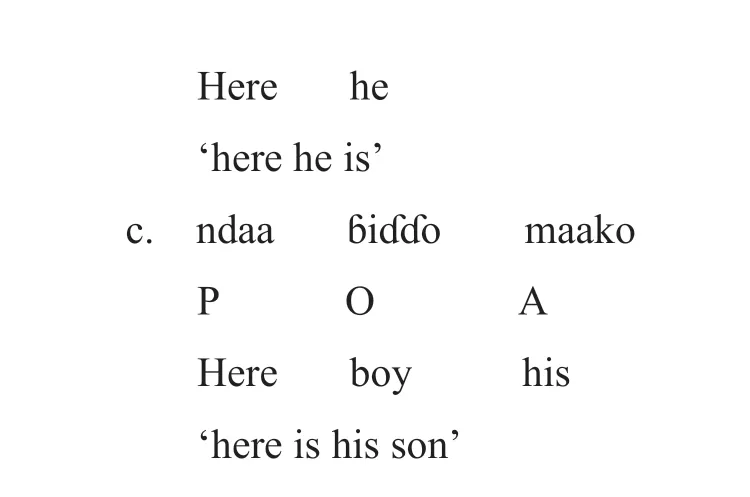

The fourth type of the non-verbal sentence has a predicator with object and adjunct or without both as a grammatical requirement. The predicator is one of the quasi-verbal interjections having some verbal features for making clarification. Consider the following examples.

In the above examples, the object or the object element appearing after the predicate constitutes the nominal group while the adjunct is the adverbial group. Here, according to Arnott (1970) ndaa and hiin are both used alternatively in this type of non-verbal sentence, but such a case of hiin is rarely found in Adamawa dialect of Fulfulde.

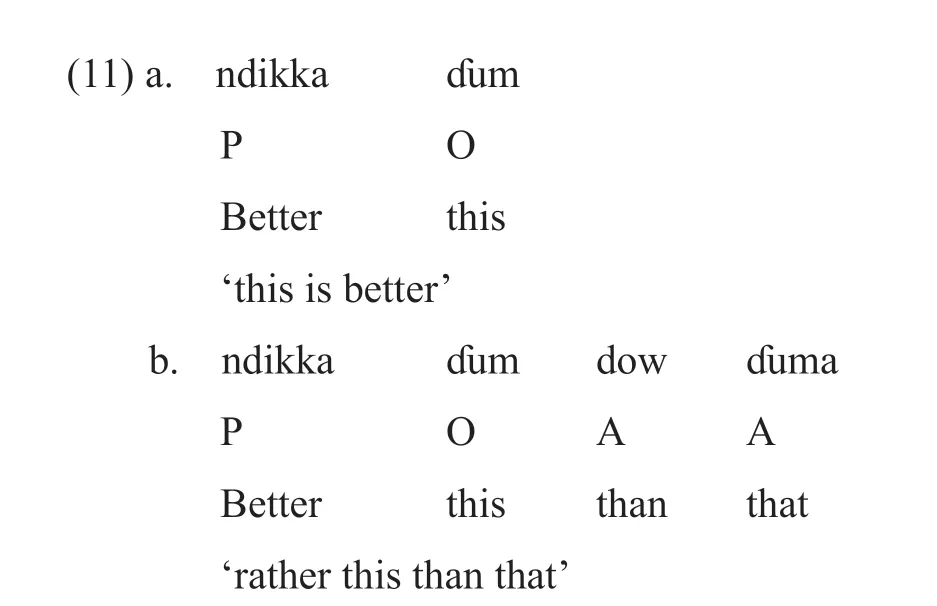

The fifth type of non-verbal sentence resembles the fourth type but the object is constant. It has a predicator and an object, with or without adjunct(s). The predicator is equally one of the quasi-verbal forms of ndikka (or ’igga) ‘rather’ or ‘better’. Let us consider the following examples:

In the above examples, the object is the nominal or adverbial group (not an object element, as in the fourth type) then the adjunct constitutes the adverbial group, particularly the one consisting dow (over/rather than) with another nominal or adverbial group. Similarly, Arnott (1970) provides the alternative use of ndikka and igga in his examples; we observed that in essence igga is rarely found in Adamawa Fulfulde.

However, Daudu (2005) refers to the third, fourth and fifth types of non-verbal sentences as exemplified above, as having both external and internal arguments, which are coordinated by an auxiliary verb. McIntosh (1984, pp. 54-55) refers to them as those non-verbal sentences expressing attribution, identification and location or existence. Arnott (1970, p. 33) concludes on the non-verbal sentences that “apart from the absence of a verbal form in these types of sentences, the most important thing about them is the occurrence of subject and object elements as subject and object respectively. Whereas where they occur in verbal sentences they function as part of the verbal complex.” The sentences therefore contain virtually a prelude; a preliminary element or phrase marked off in some way from the remainder constituting an emphatic form of each sentence. The sentences are derived ones as they cannot be their underlying forms, which prompted movement of categories. Some non-verbal sentences have only one-element clause like non, which means ‘it is so’. A clause like that is negated by naa as in saying naa non meaning ‘it is not so’. See also Daudu (2005).

Minimalist Programme

In the early 1960s, linguists were trying to explain language acquisition and linguistics variation with the formal framework which relied on rules and constructions to explain grammar. By the early 1980s, linguists were building on the earlier theories with a new framework that sought to eliminate this reliance on rules and constructions in favour of a more generalized explanation of language acquisition. Perhaps the most widely-known instance of the principles and parameters framework was Government and Binding theory, which was primarily concerned with abstract syntactic relations. The research conducted in Government and Binding yielded promising results, and was widely accepted. According to Hornstein (2005), Government and Binding did not explain everything; it was viewed as “absolutely correct, in outline”. However, there was still a problem: the system that Government and Binding described was still very complex.

In the early 1990’s, the minimalist programme was presented as a solution to this complexity. The minimalist programme takes the assumption that language is a “perfect system” and that the faculty of language fits the constraints of this system in the most efficient way possible (Chomsky, 1995, p. 1). Within this assumption, the minimalist programme attempts to uncover how this optimal system is structured and what its underlying mechanisms are.

The minimalist programme takes into account “two types of economy considerations” (Hornstein, 2001, p. 1). The first of the two types is methodological economy. This type of economy considers factors “such as simplicity and parsimony”, and attempts to reduce the number of factors, modules and principles present in any given theory. The second type of economy is “substantive economy” which places a value on the available resources: derivations should be as computationally efficient as possible, maximizing resources (Hornstein, 2005, p. 6).

Wh-Movement in Minimalist Programme

Chomsky (1995) suggests that wh-movement is triggered by a strong operator feature of the functional C-head: “the natural assumption is that any C may have an operator feature and this feature is a morphological property of such an operator as wh-. For an appropriate C, the operator is raised for feature checking to the domain of C:[spec,Cp]” thereby satisfying their scopal properties (Chomsky, 1995, p. 199). If the operator feature on C is strong, movement is overt (e.g. English). Consequently, if the operator feature is weak, wh-movement is postponed (e.g. Chinese). However, the trigger of movement overt or covert is always located on a target.

In minimalist inquiry Chomsky (2000, p. 44) modifies the proposal, dispensing with LF movement: all movement operations must happen before the point of spellout. Wh-movement in this framework has the following mechanism: “the wh-phrase has an interpretable feature [wh-] and an interpretable feature [q], which matches the uninterpretable probe [q] on C, seeks the goal, a wh-phrase, and once the probe locates the goal, F [wh-] are checked and deleted. This feature checking is done by means of agreement, no movement is involved.” According to Chomsky (2000), the uninterpretable [wh] feature of a wh-phrase is “analogous to structural case for nouns”. Consequently, it does not have an independent status, but is a reflex of certain properties of Q.

Since uninterpretable features are checked without triggering movement, in order to account for the displacement of a wh-phrase, Chomsky postulates an EPP-feature on a C head. He suggests that the EPP-feature of C is similar to the T. It requires [spec. CP] to be filled which results by the displacement of a wh-phrase.

Wh-Question in Fulfulde

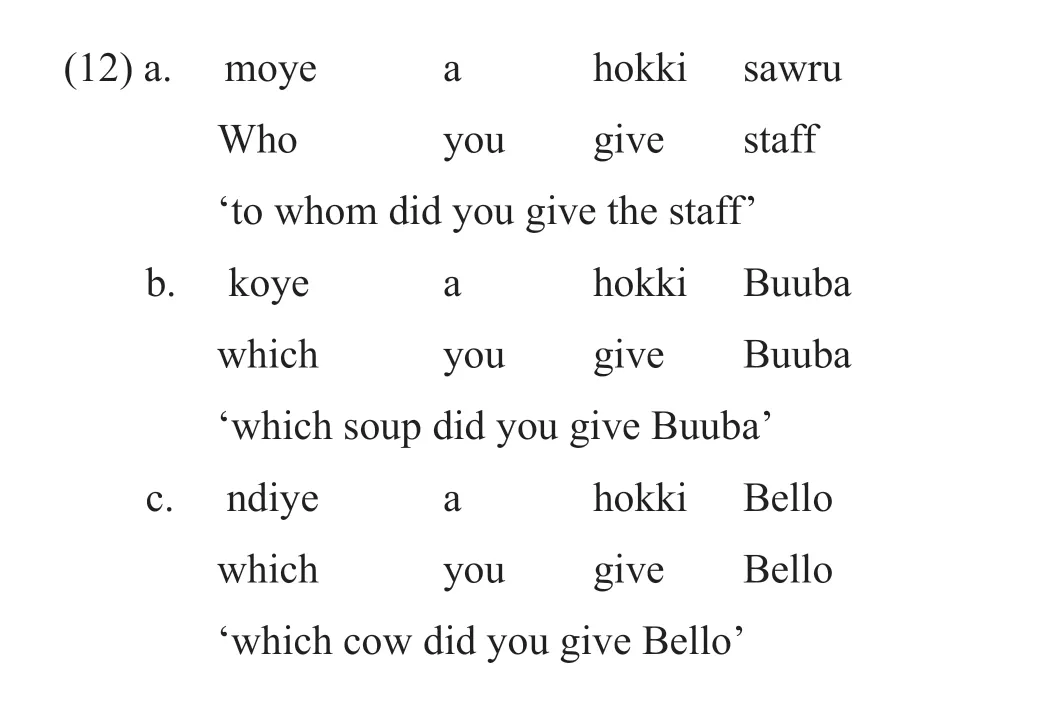

There are many wh-interrogative markers in Fulfulde; the wh- or interrogative markers are the -ye or -e suffixes bound to the stem of the pronouns and some prepositions. A pronoun that ends with a vowel takes -ye suffix, while one ending with a consonant takes -e suffix. (see Arnott, 1970; McIntosh, 1984; Daudu, 2005). Let us consider the following examples:

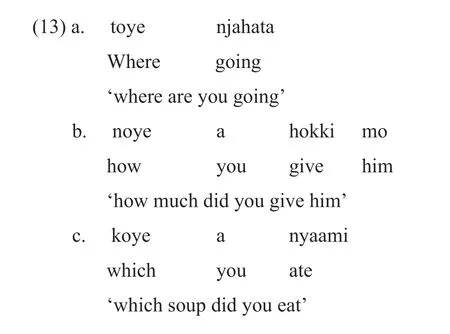

In the above examples we would notice that the interrogative markers are derived from the very available nominal classes of Fulfulde by suffixing -ye or -e to the stem of pronouns. Some prepositions that can equally derive wh-interrogative markers by adding -ye or -e as in the above are to, no, and ko: to will derive toye (where), no will derive noye (how), and ko will derive koye (what). Let us consider the following examples:

From the above examples, it is important to categorically state that some whinterrogative operator expressions remain in place. Such structures are sometimes referred to as wh-in-situ question (i.e. in place) in its canonical position (i.e. usual). Let us consider the following examples:

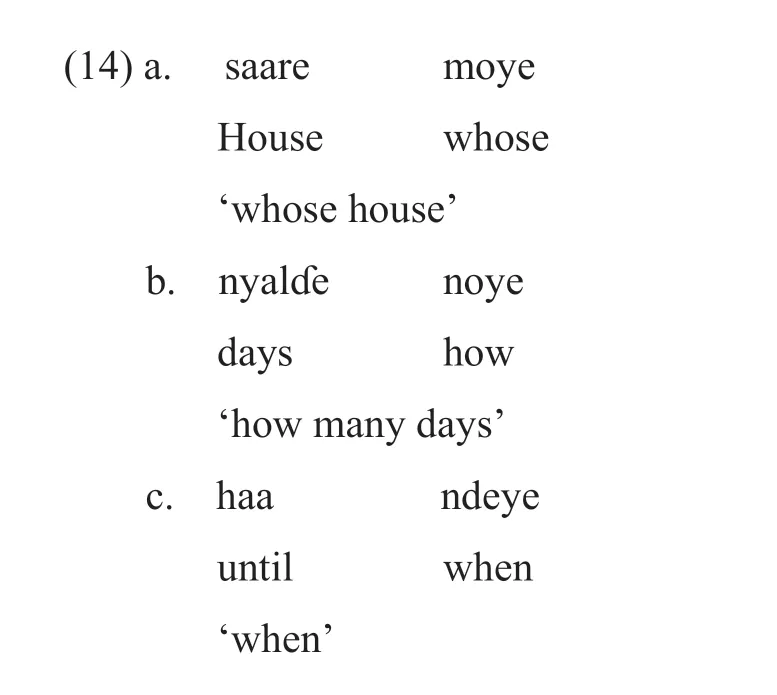

In the above examples, the interrogative markers are preceded by the subject of the sentence and they are moye (whose), noye (how), and ndeye (when). They all occur to the right of their head, not left, at the end of the sentences as complement, respectively. This is the reason why the interrogative markers remain in-situ. By fronting the interrogative markers, it will render the sentence ungrammatical.

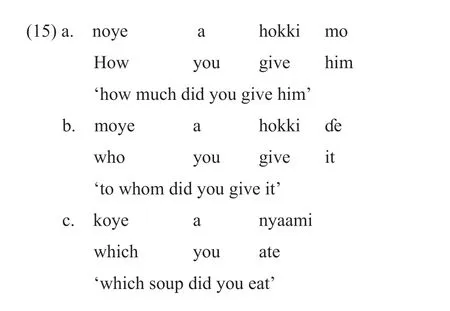

However, when interrogative elements move, they get fronted to the initial position of the sentence or clause. They get preposed from their canonical position in declarative sentences. Let us consider the following examples:

In the above examples, all the interrogative markers are fronted. The sentences exhibit good examples of wh-preposing. The interrogative markers noye, moye, koye being fronted will move and the landing site of the elements is the spec, CP, crossing the DP subject complement in IP specifier position. Let us consider the following example:

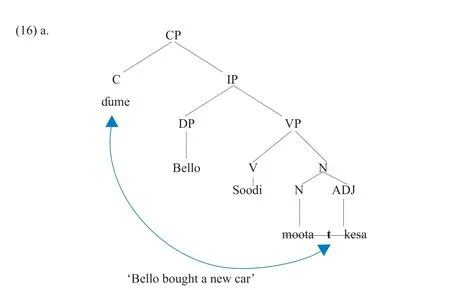

From the above illustration, the lexical items moota and kesa are merged and moved from R- to -L in binary form because it involves the movement of two different lexical items. This leaves a trace which indicates the wh-movement fulfilling a number of criteria, i.e. checking a feature. This feature moves to function as the ‘head’ that is an ‘attractor’ attracting feature in the initial position. Here, a case of pied-piping often results in the movement of the attractors from L-to-R moving in multiples rather than single.

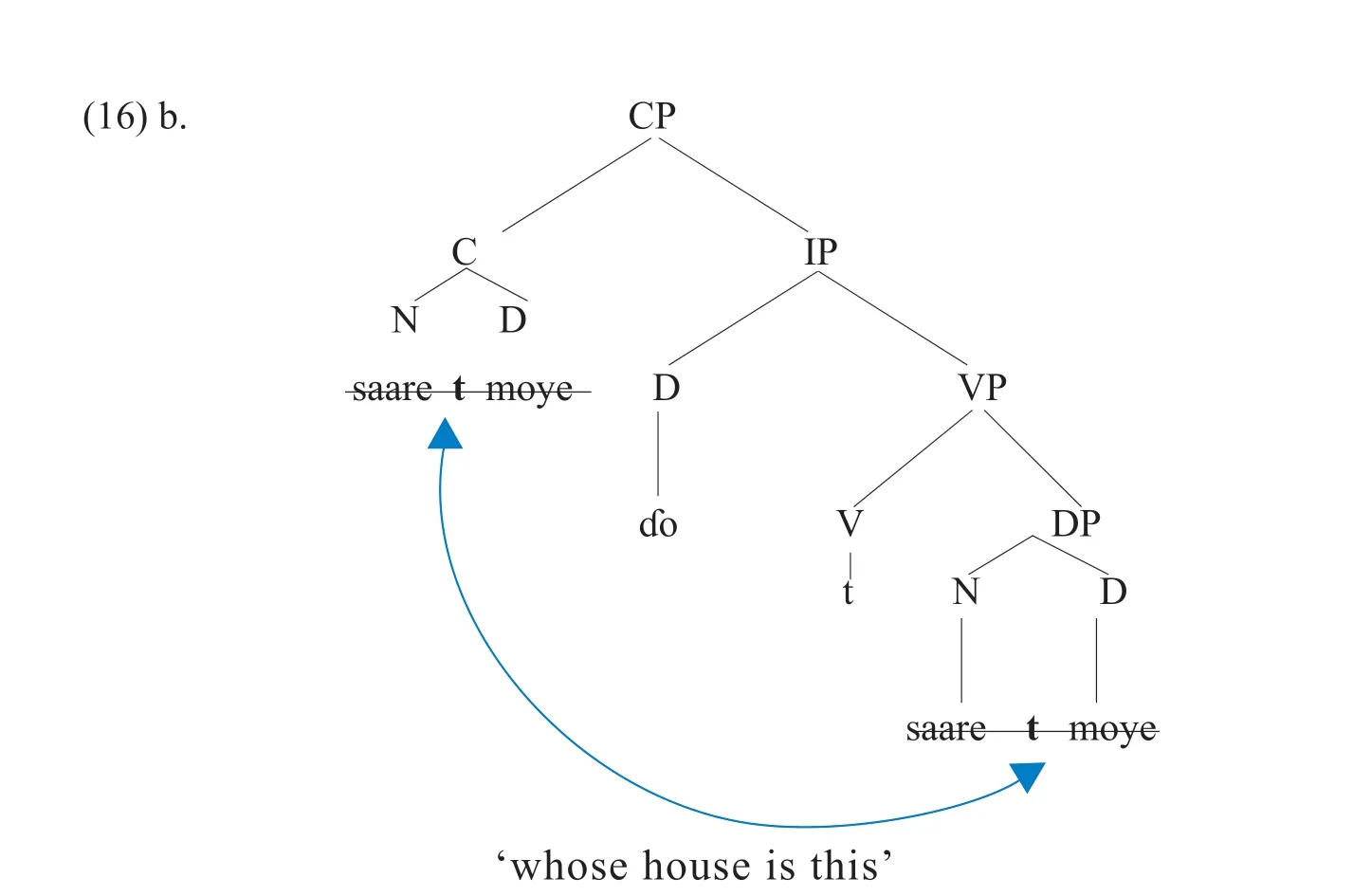

However, the movement which shows a clear case of pied-piping of the whmovement follows the independent properties of the PF (phonetic form) or of LF (logical form). Chomsky (1995) claims that movement of this nature which is within covert syntax consists purely of the feature movements that occur only in the overt syntax. As the same wh-question cannot move at all, Chomsky (1995) gives two conditions as ‘interpretable’ and ‘uninterpretable’ features. Let us consider the following example:

In the above example, we have interpretable features, i.e. the movement of the whquestion which follows the independent properties of the LF. This is best described as the movement of saare moye (whose house) to the initial position R- to -L movement moving in numeration rather than in single form. However, when you have moye (who) moving alone to the initial position of the sentence, then what you may likely have is an uninterpretable feature of both the PF and/or of LF. This makes the sentence ungrammatical; such is the case when there is a movement of saare (house) alone, still what you have is an uninterpretable feature. Therefore, what we have here is basically movement of the entire node saare moye (whose house) which cannot be separated, but rather moved together to be grammatical or to check features (+agreement).

Preposition Stranding

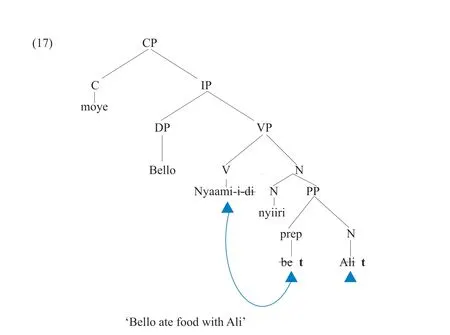

Preposition stranding is a phenomenon of stranding of material at the immediate landing site under movement. The subordinate preposition is pied-piped along with the interrogative pronoun so that the whole PP moves to spec-C position. This PP in turn is merged within the verb of the sentence indicating that the action is collectively done. The VP is then merged with the DP forming the IP. The following example illustrates further:

From the above example, the subordinate preposition be is pied-piped along with the interrogative pronoun moye, so that the whole PP be moye moves to spec-C position. Here, this PP in turn is merged within the verb of the sentence nyaamdii indicating that the action is collectively done. The VP is then merged with the DP forming the IP which we have Bello nyaam-dii nyiiri. Merging the resulting IP with the null complementizer which is the edge feature gives the structure of the above construction Moye Bello nyaam-dii nyiiri? However, the PP be Ali originates as the complement of the verb nyaam-. That is to say Ali is the complement of the preposition be and nyiiri is the specifier. The whole PP be Ali moves to the front of the main clause. If the specifier nyiiri merges with the complement Ali to form the structure [nyiiri Ali]. The wh-word moye then raises to become the specifier of nyiiri forming the overt N nyiiri be moye. The resulting N nyiiri be moye is merged to the verb nyaam-ii-di forming nyaam-ii-di nyiiri be moye. If moye undergoes whmovement on its own in subsequent stages of derivation, we derive moye Bello nyaam-ii-di nyiiri. If wh-question moye moves on its own, the preposition will be stranded in the most deeply embedded spec-C position which renders the sentence ungrammatical because the preposition is stranded.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this work examines the nature of wh-movement in Fulfulde using the minimalist programme. We have identified and discussed four types of whmovement in Fulfulde i.e. subject, complement, preposition which is similar to that of English pied-piping and preposition stranding. There is a case of subject preposed from canonical position in declarative sentences to a new position in interrogative sentences. There are both left to right movement and right to left movement as the case may be that account for both phonetic form and logical form. In some wh-movement, the question remains in place called wh-in-situ. However, if the interrogative markers get fronted (wh-ex-situ) the movement is equally grammatical. Therefore, if a movement occurs, each move element leaves behind a trace marked by ‘t’; the trace is co-indexed so that we can see the extraction sites and the landing sites of the elements that have moved.

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年1期

Language and Semiotic Studies2020年1期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- The Peircean Sign as a Model for Interpreting Semiotic Structures in Mandarin Chinese

- The Effect of Para-Social Interaction in Endorsement Advertising: SEM Studies Based on Consumers’ Exposure to Celebrity Symbols

- Memes as Ideological Representations in the 2019 Nigerian Presidential Campaigns: A Multimodal Approach

- Perception of Myth in Print and Online Media

- Salomé: A Tragic Muse to Modern Chinese Drama