Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease mimicking acute cerebellitis: A case report

Jiao-Jiao Guo, Zi-Yi Wang, Meng Wang, Zong-Zhi Jiang, Xue-Fan Yu

Jiao-Jiao Guo, Zi-Yi Wang, Meng Wang, Zong-Zhi Jiang, Xue-Fan Yu, Department of Neurology and Neuroscience Center, The First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun 130021, Jilin Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease (NIID) is an unusual autosomal dominant, chronic progressive neurodegenerative disease. The clinical manifestations of NIID are complex and varied, complicating its clinical diagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to document sporadic adult-onset NIID mimicking acute cerebellitis (AC) that was finally diagnosed by imaging studies, skin biopsy, and genetic testing.CASE SUMMARY A 63-year-old man presented with fever, gait unsteadiness, dysarthria, and an episode of convulsion. His serum levels of white blood cells and C-reactive protein were significantly elevated. T2-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging and fluid attenuation inversion recovery sequences showed bilateral high-intensity signals in the medial part of the cerebellar hemisphere beside the vermis. While we initially considered a diagnosis of AC, the patient’s symptoms improved significantly without special treatment, prompting our consideration of NIID. Diffusion-weighted imaging showed hyperintensity in the corticomedullary junction. Skin biopsy revealed eosinophilic inclusions positive for anti-p62 in epithelial sweat-gland cells. GGC repeat expansions in the Notch 2 N-terminal like C gene confirmed the diagnosis of NIID.CONCLUSION For patients with clinical manifestations mimicking AC, the possibility of underlying NIID should be considered along with prompt rigorous examinations.

Key Words: Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease; Acute cerebellitis; Skin biopsy;Genetic testing; Magnetic resonance imaging; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Neuronal intranuclear inclusion disease (NIID) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by the presence of eosinophilic hyaline intranuclear inclusions in the central, peripheral, and autonomic nervous systems, as well as visceral organs[1].NIID is classified according to the age of onset and its genetic etiology: Infantile,adolescent, and adult types; and sporadic and familial types; respectively[2]. NIID induces varying clinical manifestations, including pyramidal and extrapyramidal symptoms, dementia, convulsions, syncope, tremor, and autonomic dysfunction[3].While a high-intensity signal along the cortical medullary junction on diffusionweighted imaging (DWI) is a classic imaging feature of NIID[4], the condition has also been associated with cerebellar abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).The poor evaluation of these cerebellar abnormalities often results in misdiagnosis.NIID has recently been attributed to the repeated amplification of GGC sequences of the Notch 2 N-terminal like C (NOTCH2NLC) gene, providing a basis for genetic diagnosis[5].

We herein report the case of a patient with sporadic adult-onset NIID. The patient’s clinical course began with his manifestation of rare symptoms, and a diagnosis of NIID was finally confirmed by pathology and genetic studies. This case report recommends that a diagnosis of NIID be considered when patients present with clinical manifestations resembling acute cerebellitis (AC).

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 63-year-old Chinese man was admitted to the hospital complaining of fever,worsened gait unsteadiness, dysarthria, and vomiting for one day. His wife stated that he experienced a transient episodic convulsion. He was conscious during the convulsion, which had alleviated after 20 s.

History of present illness

During the 4 mo prior to his presentation at the hospital, the patient exhibited gradual deterioration of his memory and attention, as well as the onset of mild depressive symptoms; he would occasionally experience difficulty expressing himself, was unwilling to talk to others, and exhibited indifference during this period. His wife stressed that they did not consider her husband’s condition seriously, as his clinical symptoms were not persistent.

History of past illness

The patient had a 5-year medical history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia. He had been sweating excessively and experienced constipation for about 1 year without any recent weight loss.

Personal and family history

The patient denied any history of viral infection or autoimmune disease. He had no notable family history and consumed a moderate amount of alcohol for 30 years.

Physical examination

His vital signs were as follows: Temperature of 38 ˚C, pulse rate of 66 beats/min with a regular rhythm, and blood pressure of 150/90 mmHg. His respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and chest and abdominal examinations were all normal.

Neurological examination

The patient had poor consciousness, dysarthria, and a drawling speech. His pupils were equal in size, round, but abnormally small in diameter (d = 1.5 mm); they were sensitive to direct and indirect light stimulation. He had mild horizontal nystagmus.His muscle strength and tone were normal. His tendon reflexes had diminished. The patient had obvious ataxia and no meningeal irritation. The findings of the other neurological examinations were unremarkable.

Laboratory examinations

The lumbar puncture revealed the following: Intracranial pressure, 140 mmH2O;protein level, 0.72 g/L (normal, 0.15-0.45 g/L); immunoglobulin G, 38 mg/L (normal,0-34 mg/L); and glucose, ion, and cell number, normal. Routine blood tests revealed that the patient's leukocyte count was high at 13.5 × 109/L (normal, 4-9 × 109/L), with a neutrophilic percentage of 57%. C-reactive protein was found to be 28 mg/L (normal,0-10 × 109/L). No viruses or bacteria were found in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid.The results of the other laboratory tests were unremarkable.

Imaging examinations

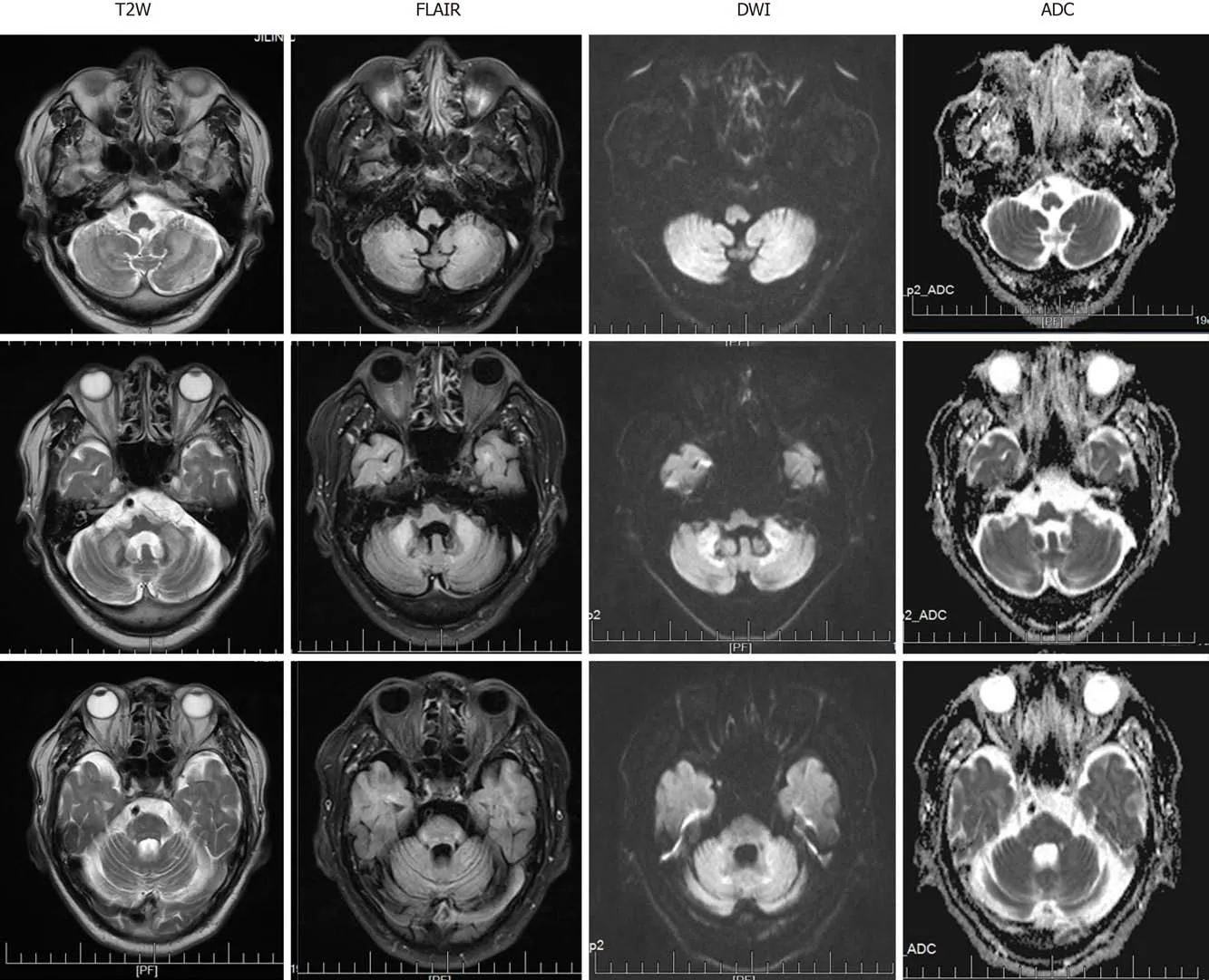

At the level of the cerebellum, MRI revealed symmetrical slightly high-intensity signals in the bilateral cerebral hemispheres, middle cerebellar peduncle, and paravermal regions. These findings were associated with atrophy of the vermis on T2-weighted (T2W) and fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences(Figure 1). The corresponding lesions were characterized by high signal intensity on DWI sequences (Figure 1).

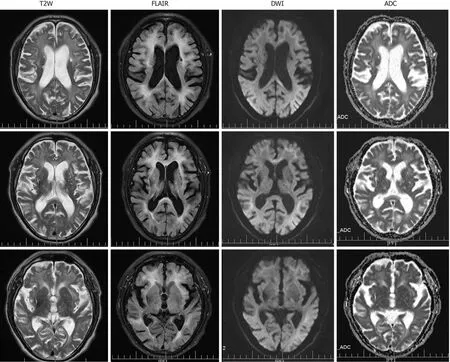

At the level of the cerebrum, T2W images demonstrated multiple old lacunar infarcts in the bilateral basal ganglia and cerebral atrophy (Figure 2). The DWI showed high-intensity signals that extended along the corticomedullary junction but not into the deep white matter (Figure 2). Furthermore, the T2W and FLAIR sequences revealed significant leukoencephalopathy around the paraventricular region of the bilateral lateral ventricles. The corresponding leukoencephalopathy was associated with slightly hyperintense signals on the apparent diffusion coefficient sequence(Figure 2).

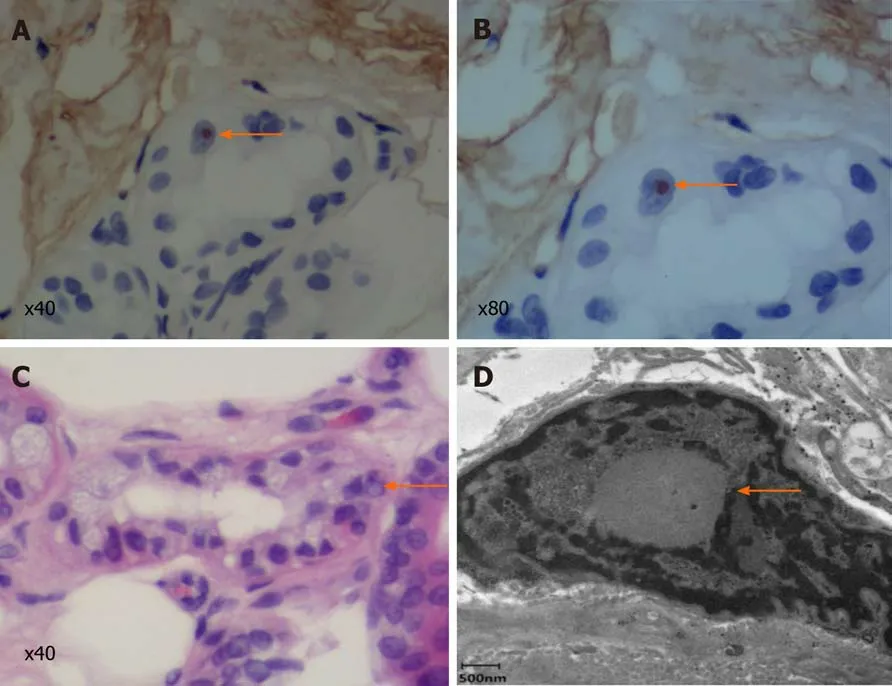

Pathological examination

A biopsy specimen of 6 mm in diameter was obtained from 10 cm above the lateral malleolus after the administration of local anesthesia. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions in the nucleus of sweat duct epithelium under a light microscope, while immunohistochemical staining showed that the inclusion bodies were positive for anti-p62 (Figure 3). Under an electron microscope,spherical inclusion bodies composed of fibrous substances without membranes were noted (Figure 3).

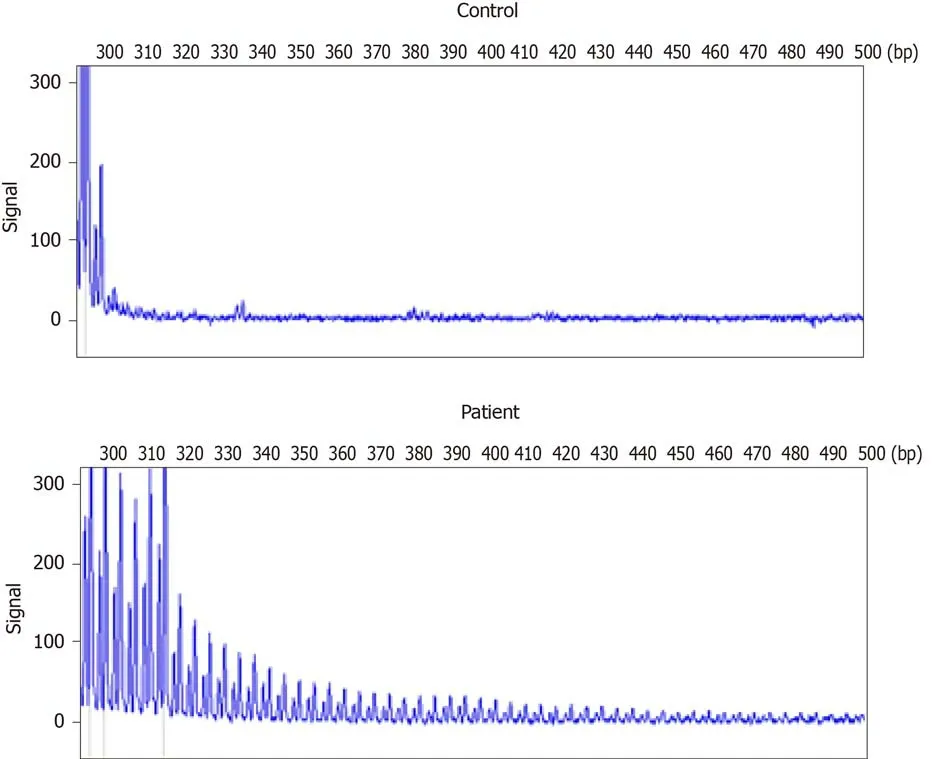

Genetic testing

A repeat-primed polymerase chain reaction assay revealed 72 GGC repeats in the 5′untranslated region of NOTCH2NLC (Figure 4). Screening for theFMR1gene mutation excluded a diagnosis of fragile X–associated tremor ataxia syndrome.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

We excluded infectious, immune-mediated, metabolic, and acute cerebellar ataxia(ACA) with a genetic etiology. The patient was eventually diagnosed with sporadic adult-onset NIID based on the clinical presentation and his imaging, pathology, and genetic testing results.

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging obtained at the level of the cerebellum. Bilateral high signal intensities in the cerebral hemispheres and middle cerebellar peduncle are visible. Cerebellum atrophy is evident. T2W: T2-weighted; FLAIR: Fluid attenuation inversion recovery; DWI: Diffusion-weighted imaging;ADC: Apparent diffusion coefficient.

TREATMENT

After the diagnosis of NIID, the patient was not treated with any pharmacotherapy,but rather, with physical cooling, rehydration, and nutritional support therapy.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient’s temperature returned to normal on the second day of admission. On the sixth day, he could speak freely with others and walk normally. Dysarthria and nystagmus improved within 2 wk, and his ataxia gradually disappeared. By the 2-mo follow-up, the patient had become able to take care of himself, and there was no change in his score on the neuropsychological rating scale.

DISCUSSION

The patient considered in the present report presented only with fever and ACA, a common clinical manifestation of AC. Serological examination suggested a high probability of infection. Brain MRI showed symmetrical abnormal signals in the bilateral cerebellum. These findings informed an initial diagnosis of AC, but the absence of pathogens in the patient's serum and cerebrospinal fluid and self-limiting nature of the patient’s symptoms ruled out this diagnosis. This unusual clinical presentation prompted our consideration of rare diseases.

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance imaging obtained at the level of the cerebrum. Diffusion-weighted imaging showed high-intensity signals along the corticomedullary junction. Both T2-weighted and fluid attenuation inversion recovery sequences showed marked cerebral atrophy, white matter degeneration, and old cerebral infarctions. T2W: T2-weighted; FLAIR: Fluid attenuation inversion recovery; DWI: Diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC: Apparent diffusion coefficient.

Patients with NIID may reportedly develop either subacute or chronic cerebellar ataxia without any outbreaks. Moreover, the literature also features a report of NIID mimicking an encephalitis attack without cerebellar involvement[6]. In addition to presenting with acute symptoms, the patient also had chronic symptoms, such as dementia and peripheral and autonomic nerve damage that suggested a diagnosis of NIID. Observed in 94.7% of cases of sporadic NIID, dementia is the most common clinical symptom of the disorder and was the patient’s main reason for seeking neurological consultation[3,7]. Peripheral nerve involvement includes sensory disturbance, including the loss of slight and sense of vibration, as well as peripheral limb numbness[3]. A nerve conduction study should be performed in the case without high sign on DWI because over 90% of patients with NIID present with subclinical neuropathy[3,8]. Autonomic involvement includes narrowing of the pupils, dysuria, and constipation[9]. Acute symptoms such as convulsions, syncope, and vomiting tend to be intermittent in patients with NIID[3]. The reversibility of these acute symptoms can help inform a diagnosis of NIID.

In the present case, linear DWI signs and abnormal signals in the bilateral cerebellar hemispheres were accompanied by significant leukoencephalopathy and different degrees of atrophy in the cerebrum and cerebellum. In cases of NIID, abnormal signals observed along the corticomedullary junction on DWI and diffuse white matter hyperintensities on FLAIR have been considered as characteristics of the disease[4,10].Studies have found that hyperintensity in the white matter is associated with pathological spongiform changes and diffuse non-spongiform myelin pallor[11]. It is worth noting, however, that the latter findings are also associated with diseases of other etiologies, including inflammatory (especially AC), neoplastic,neurodegenerative, metabolic, and demyelinating diseases. Furthermore, symmetrical cerebellar lesions and cerebellar atrophy can also indicate NIID[12,13]. Therefore, NIID can be misdiagnosed as cerebellitis with abnormal signals in the cerebellum or as a multisystem neurodegenerative disease with white matter damage. A recent study showed that only approximately 37.5% of affected familial individuals exhibit typical NIID radiological manifestations[14], which means that histopathological and genetic diagnosis are particularly important.

Figure 3 Skin biopsy specimen. A and B: Immunohistochemical staining showed that the inclusion bodies were positive for p62 (arrows; A: × 40; B: × 80); C:Hematein eosin staining reveals eosinophilic inclusion bodies (arrow; × 40); D: Electron microscopy. The red arrow indicates a spherical inclusion body composed of fibrous substances without membranes.

Figure 4 Repeat-primed polymerase chain reaction analysis. A: Normal control panel shows no repeat expansion; B: Panel of the patient shows the stripe-shaped pattern of expanded repeats of GCC located in the Notch 2 N-terminal like C.

Skin biopsy is an effective and a less invasive diagnostic tool than autopsy or rectal biopsy with which to diagnose NIID[15]. Under electron microscopy, the intranuclear inclusions are circular, non-membrane bound structures composed of filamentous material. These eosinophilic inclusions are immunopositive for ubiquitin and p62,meaning that they are closely related to the inactivation of the proteolytic enzyme system[16]. However, as similar inclusion bodies have also been found in association with polyglutamine disease, skin biopsy is not a specific diagnostic tool for NIID[17].Although the accumulation of abnormal proteins or the dysfunction of the nuclear protein degradation system may be the primary pathological cause underlying NIID,other specific etiologies or pathogenetic mechanisms remain obscure.

NIID lacks complete diagnostic criteria. Previously proposed diagnostic criteria include symptomatic and pathological evidence but not genetic findings[3]. Soneet al[5]recently demonstrated that the repeated amplification of the GGC sequence in the noncoding region 5′-untranslated region of human specificNOTCH2NLCgene, also called NBPF1, can cause NIID[5]. This finding refutes previous theories that have attributed NIID to polyglutamine disease. Furthermore, other research studies have implicated the GGC repeat amplification ofNOTCH2NLCgene in the pathophysiological processes underlying various neurodegenerative diseases including multiple system atrophy, AD, PD, essential tremor, and leukoencephalopathy[5,18,19]. This literature suggests that NIID-related disorders encompass a spectrum of diseases caused by the expanded GGC repeat withinNOTCH2NLCgene[14]. The present report supports this concept by demonstrating that extended mutations in non-coding regions involving the same repeat sequences can indicate overlapping diseases or induce clinical manifestations suggestive of several diseases. It also underscores the possibility that the same genetic cause can underlie various diseases[14,20]. We successfully detected the presence of GGC repeat amplification in our patient and confirmed the diagnosis of NIID. Furthermore, considering the wide distribution of intranuclear inclusions in the patient’s nervous system and other organs, our report supports the possibility of additional phenotypes of NIID. However, the mechanism by which abnormal GGC repeat amplification in theNOTCH2NLCgene leads to these different phenotypes remains unclear.

CONCLUSION

We document the rare case of a patient with NIID mimicking AC that was eventually diagnosed by imaging, pathology, and genetic evaluations. The wide range of clinical phenotypes of NIID complicates its diagnosis, especially in cases of adult-onset NIID.This report underscores the need to consider the possibility of NIID when patients exhibit fever and ACA with MRI findings of high-intensity signals in the cerebellum.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年23期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年23期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Understanding the immunopathogenesis of COVID-19: Its implication for therapeutic strategy

- What is the gut feeling telling us about physical activity in colorectal carcinogenesis?

- Latest developments in chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction

- Correlation between ductus venosus spectrum and right ventricular diastolic function in isolated single-umbilical-artery foetus and normal foetus in third trimester

- Clinical efficacy of integral theory–guided laparoscopic integral pelvic floor/ligament repair in the treatment of internal rectal prolapse in females

- Treatment of Kümmell’s disease with sequential infusion of bone cement: A retrospective study