Diffusion-weighted imaging might be useful for reactive lymphoid hyperplasia diagnosis of the liver: A case report

Taro Tanaka, Kazuhiro Saito, Daisuke Yunaiyama, Jun Matsubayashi, Yuichi Nagakawa, Maki Tanigawa,Toshitaka Nagao

Taro Tanaka, Kazuhiro Saito, Daisuke Yunaiyama, Department of Radiology, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo 1600023, Japan

Jun Matsubayashi, Maki Tanigawa, Toshitaka Nagao, Department of Anatomic Pathology, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo 1600023, Japan

Yuichi Nagakawa, Department of Gastrointestinal and Pediatric Surgery, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo 1600023, Japan

Abstract BACKGROUND Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) of the liver is a rare liver lesion. It is considered difficult to differentiate radiologically from hepatocellular carcinoma,metastatic liver tumor and other pathologies.CASE SUMMARY A 54-year-old woman presented to our hospital with RLH of the liver. The patient had a diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma of the liver from an unknown origin and subsequently underwent partial hepatectomy. However, histopathological analysis revealed RLH. The lesion showed perinodular enhancement in the arterial phase on contrast-enhanced computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. On diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), we encountered linear hyperintensity along the portal tract consecutive to the liver lesion, which is a new characteristic radiologic finding. This finding corresponded to the lymphoid cell infiltration of the portal tract. Furthermore, there was strongly restricted diffusion on the apparent diffusion coefficient map. We used these characteristic radiologic findings to diagnose the lesion as a lymphoproliferative disease.CONCLUSION The linear hyperintensity consecutive to the liver lesion on DWI provided additional valuable diagnostic information.

Key Words: Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia; Pseudolymphoma; Magnetic resonance imaging; Diffusion-weighted imaging; Perinodular enhancement; Portal tract infiltration;Case report

INTRODUCTION

Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (RLH) is a benign condition of unknown etiology that was first described in the English literature in 1972[1]. RLH occurs throughout the entire body and occurs predominantly in middle-aged women and is associated with chronic liver disease, autoimmune disease and malignant tumors. RLH of the liver is rare and difficult to distinguish radiologically from hepatocellular carcinoma,metastatic liver tumor and other pathologies[2-7]. Most cases of RLH of the liver have shown perinodular or moderate enhancement in the arterial phase on contrastenhanced computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[4,5,8,9].Obvious restricted diffusion, which is stronger than that of the spleen, is another characteristic sign[10]. Herein, we propose the additional characteristic radiologic finding on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI).

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

There were no chief complaints.

History of present illness

A 54-year-old woman underwent abdominal ultrasound during a medical checkup,which revealed liver lesions. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed well-defined hypoechoic lesions in liver segments 1 and 2.

History of past illness

She had no history of persistent viral infection, autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease or malignant tumors. She had a medical history of polyp in the pharynx and maxillary osteomyelitis.

Physical examination

There were no physical findings to note.

Laboratory examinations

Blood tests revealed normal liver function and were negative for hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B core antibody, hepatitis C antibody, and antinuclear antibody. Her tumor marker levels were as follows: alpha-fetoprotein, 2.1 ng/mL; PIVKA-2, 21 mAU/mL; carbohydrate antigen 19-9, 4.1 U/mL; and carcinoembryonic antigen, 2.3 ng/mL. All markers were in the normal range.

Imaging examinations

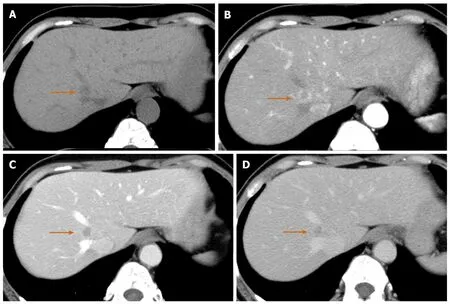

Precontrast CT showed three liver nodules with slight low attenuation relative to the liver parenchyma at segments 1, 2 and 8 (Figure 1A). There was perinodular enhancement (PNE) in the arterial phase in the nodules (Figure 1B) with washout of contrast medium in the portal and equilibrium phase (Figure 1C and 1D). On precontrast MRI, the nodules showed hypointensity on T1-weighted image and hyperintensity on fat-saturated T2-weighted image (Figure 2A and 2B). There was no fat component. The nodule showed obvious hyperintensity on DWI (b = 800 m2/s) and strongly restricted diffusion on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) mapping (ADC of the lesion: 0.54 × 10-3mm2/s, ADC of the spleen: 1.03 × 10-3mm2/s). There was linear hyperintensity along the portal tract consecutive to the liver lesions on DWI (Figures 2C and 3D). However, that of the S2 lesion was faint because of heart beating heart and susceptibility artifact. On gadoxetic acid-dynamic enhanced MRI, the nodule showed PNE in the arterial phase (Figure 2D), washout of contrast medium in the portal and transitional phase and low signal intensity in the hepatobiliary phase(Figure 2E and 2F).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Because we considered the PNE to be a ring-like enhancement, we believed these lesions to be metastatic tumors of unknown origin.

TREATMENT

The patient underwent a partial hepatectomy to obtain a definitive diagnosis and partial resection of the liver (segments 2 and 8) for the two superficially located lesions.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

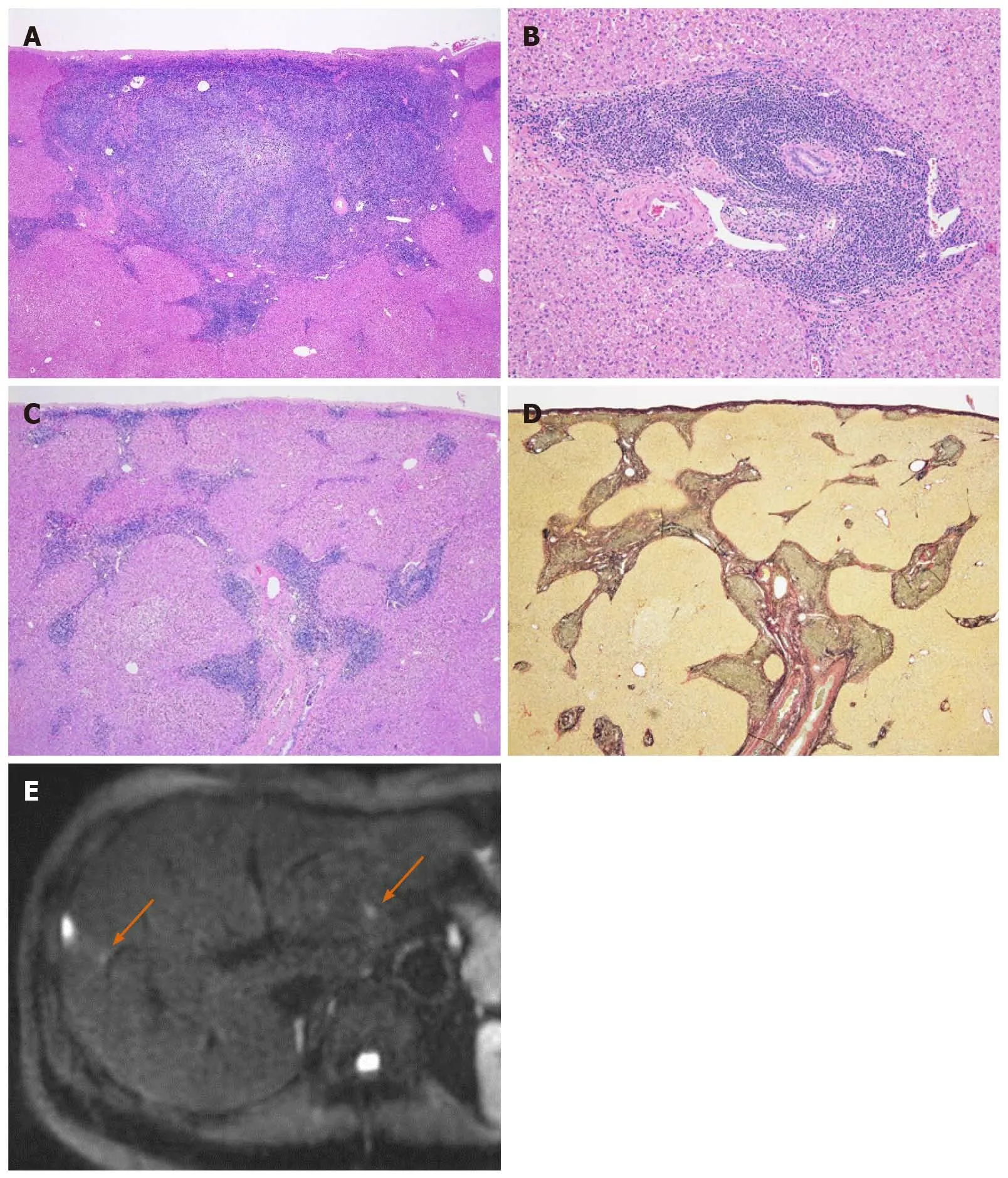

Grossly, there were two well-circumscribed whitish nodules in the subserosa region.Histopathologic examination showed the dense mature lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration in these nodules, which formed various-size lymphoid follicles with enlarged germinal centers. The presence of tingible body macrophages and lack of expression of BCL2 protein at the germinal center signified nonneoplastic follicles.Scattered large lymphoid cells with prominent nucleoli were also seen mainly in the interfollicular region. These large cells were CD30-positive B-cells, but there were no signs of Epstein-Barr virus infection or light chain restriction. When including immunohistochemical staining, we were unable to detect abnormal B-cell and T-cell distribution indicative of lymphoma. Furthermore, there were few IgG4-positive plasma cells. Therefore, we pathologically diagnosed the lesions as follicular hyperplasia. Interestingly, the lymphoplasmacytic infiltration extended to the surrounding portal tracts in a radial pattern, but there was no definite evidence of portal venular stenosis or fibrosis (Figure 3).

The patient underwent gadoxetic acid-enhanced MRI 6 mo after surgery, which showed no progression of residual tumors or relapse.

DISCUSSION

Figure 1 Computed tomography scan of a 54-year-old woman with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (arrow). A: Precontrast computed tomography showed a low density nodule in liver segment 1; B: The lesion showed perinodular enhancement in the arterial phase; C: The lesion showed washout in the portal phase; D: Although the lesion remained in low density in the equilibrium phase, the slight enhancement was observed in the lesion compared with the portal phase.

This case report focused on the linear hyperintensity along the portal tract on DWI consecutive to the mass lesion. One of the characteristic radiologic findings of RLH is strongly restricted diffusion[10]. Zhouet al[10]reported that the ADC value of RLH was lower than that of the spleen; the present case was consistent with their result. The RLH consisted of massive infiltration of mature lymphoid cells, forming lymphoid follicles of various sizes with germinal centers and with prominent sinusoidal dilatation around the lesion. Therefore, the low ADC value reflects the hypercellularity of RLH. The lymphoproliferative disease may occur with portal or sinusoidal infiltration[11]. Kobayashiet al[12]found portal tract hyperintensity on DWI, a finding that was similar to this present case. Many reports have pointed out portal tract infiltration around the lesion pathologically[3-10,12-16]. We supposed that linear hyperintensity along the portal tract is consistent with the portal tract infiltration.There was also massive hypercellularity in this linear region, which was due to infiltrating mature lymphoid cells. Therefore, similar findings of RLH nodules can be seen in this linear region on DWI.

Another characteristic finding of RLH is PNE in the arterial phase or equilibrium phase[2,4,5,8-10,13,15-18]. Yoshidaet al[16]first clarified the PNE mechanism from a histological point of view. They considered that because of the marked lymphoid cell infiltration in the perinodular portal tracts, PNE reflects increased arterial supply to the perinodular hepatic parenchyma as a result of venular portal stenosis or disappearance. On the other hand, Sonomuraet al[9]reported that the prominent sinusoidal dilatation surrounding the nodule was the main reason for the PNE. They also found no definite evidence of venular portal stenosis or fibrous tissue in the perinodular portal tracts in their case. The present case was pathologically similar to the case from Sonomuraet al.However, we did not confirm sinusoidal dilatation. We believe the amount of sinusoidal and portal tract infiltration affected the discrepancy. As mentioned above,hepatic lymphoproliferative disease demonstrates some infiltration pattern[11]; for this reason, the radiologic findings of RLH were relatively variable.

RLH is associated with some diagnostic clues. First, the RLH occurs more frequently in patients with a history, such as viral infection, autoimmune disease, inflammatory bowel disease or malignant tumors and in middle-aged women[3,4,6-8,13,15-20]. Second, PNE in the arterial or equilibrium phase and a strongly restricted diffusion on DWI are also useful diagnostic clues.

CONCLUSION

In this case, linear hyperintensity consecutive to the liver lesion on DWI was additional valuable diagnostic information. This finding indicates that the lesion is lymphoproliferative disease; thus, we can rule out hepatocellular carcinoma,cholangiocellular carcinoma or metastatic liver tumor. These findings nearly enabled us to make a diagnosis of RLH, although mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma may be present.

Figure 2 Magnetic resonance imaging of a 54-year-old woman with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (arrow). A: T1-weighted in-phase image showed the hypointense lesion on liver segment 1; B: The lesion was a hyperintensity on fat-saturated T2-weighted image; C: The lesion had obvious hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging. On serial imaging in diffusion-weighted imaging (numbered in order from the head direction), there was linear hyperintensity along the portal tract(arrowheads)consecutive to the liver lesion;D:The lesion showed perinodular enhancement in the arterial phase on gadoxetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging; E: The lesion showed washout in the portal phase; F: The lesion showed low signal intensity in the hepatobiliary phase.

Figure 3 Pathological findings and diffusion-weighted imaging of reactive lymphoid hyperplasia on liver segment 8. A: Hematoxylin and eosin stain (20 ×). Histologically, there was dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the subserosa region of the liver (segment 8), forming various-sized lymphoid follicles with enlarged germinal centers; B: Hematoxylin and eosin stain (100 ×). These cells did not invade into the hepatic lobules, and the limiting plates were preserved; C:Hematoxylin and eosin stain (20 ×). At the peripheral site of the lesion, lymphoplasmacytic infiltration extended along the portal tracts in a radial pattern; D: Elastica van Gieson stain (20 ×). There was no definite evidence of portal venular stenosis or fibrosis; E: Diffusion-weighted imaging showed the lesion corresponding to this pathologically presented lesion. There was linear hyperintensity along the portal tract close to the liver lesions (arrow).

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年21期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年21期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Strategies and challenges in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers

- Peripheral nerve tumors of the hand: Clinical features, diagnosis,and treatment

- Treatment strategies for gastric cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Oncological impact of different distal ureter managements during radical nephroureterectomy for primary upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma

- Clinical characteristics and survival of patients with normal-sized ovarian carcinoma syndrome: Retrospective analysis of a single institution 10-year experiment

- Assessment of load-sharing thoracolumbar injury: A modified scoring system