Cardiovascular impact of COVID-19 with a focus on children: A systematic review

Moises Rodriguez-Gonzalez, Ana Castellano-Martinez, Helena Maria Cascales-Poyatos, Alvaro Antonio Perez-Reviriego

Moises Rodriguez-Gonzalez, Pediatric Cardiology Division, Puerta del Mar University Hospital,Cadiz 11009, Spain

Moises Rodriguez-Gonzalez, Ana Castellano-Martinez, Biomedical Research and Innovation Institute of Cadiz, Puerta del Mar University Hospital, Cadiz 11009, Spain

Ana Castellano-Martinez, Pediatric Nephrology Division, Puerta del Mar University Hospital,Cadiz 11009, Spain

Helena Maria Cascales-Poyatos, Pediatrics Division, Motril-San Antonio Primary Care Center,Motril 18600, Spain

Alvaro Antonio Perez-Reviriego, Pediatrics Division, UGC Pediatria AG Sur Granada, Santa Ana Hospital, Motril 18600, Spain

Abstract BACKGROUND Since the beginning of the pandemic, coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) in children has shown milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Although the respiratory tract is the primary target for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), cardiovascular involvement is emerging as one of the most significant and life-threatening complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults.AIM To summarize the current knowledge about the potential cardiovascular involvement in pediatric COVID-19 in order to give a perspective on how to take care of them during the current pandemic emergency.METHODS Multiple searches in MEDLINE, PubMed were performed using the search terms“COVID-19” or “SARS-CoV-2" were used in combination with “myocardial injury” or "arrhythmia" or “cardiovascular involvement” or "heart disease" or"congenital heart disease" or “pulmonary hypertension” or "long QT" or“cardiomyopathies” or “channelopathies” or "Multisystem inflammatory system"or "PMIS" or “MIS-C” or ”Pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome" or"myocarditis" or "thromboembolism to identify articles published in English language from January 1st, 2020 until July 31st, 2020. The websites of World Health Organization, Centers for Disease control and Prevention, and the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center were reviewed to provide up to date numbers and infection control recommendations. Reference lists from the articles were reviewed to identify additional pertinent articles. Retrieved manuscripts concerning the subject were reviewed by the authors, and the data were extracted using a standardized collection tool. Data were subsequently analyzed with descriptive statistics. For Pediatric multisystemic inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PMIS), multiple meta-analyses were conducted to summarize the pooled mean proportion of different cardiovascular variables in this population in pseudo-cohorts of observed patients.RESULTS A total of 193 articles were included. Most publications used in this review were single case reports, small case series, and observational small-sized studies or literature reviews. The meta-analysis of 16 studies with size > 10 patients and with complete data about cardiovascular involvement in children with PMIS showed that PMIS affects mostly previously healthy school-aged children and adolescents presenting with Kawasaki disease-like features and multiple organ failure with a focus on the heart, accounting for most cases of pediatric COVID-19 mortality.They frequently presented cardiogenic shock (53%), ECG alterations (27%),myocardial dysfunction (52%), and coronary artery dilation (15%). Most cases required PICU admission (75%) and inotropic support (57%), with the rare need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (4%). Almost all of these children wholly recovered in a few days, although rare deaths have been reported (2%).Out of PMIS cases we identified 10 articles reporting sporadic cases of myocarditis, pulmonary hypertension and cardiac arrythmias in previously healthy children. We also found another 10 studies reporting patients with preexisting heart diseases. Most cases consisted in children with severe COVID-19 infection with full recovery after intensive care support, but cases of death were also identified. The management of different cardiac conditions are provided based on current guidelines and expert panel recommendations.CONCLUSION There is still scarce data about the role of cardiovascular involvement in COVID-19 in children. Based on our review, children (previously healthy or with preexisting heart disease) with acute COVID-19 requiring hospital admission should undergo a cardiac workup and close cardiovascular monitoring to identify and treat timely life-threatening cardiac complications.

Key Words: COVID-19; SARS-CoV-2; Congenital heart diseases; Myocardial dysfunction; Pediatric Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome; Cardiac Biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) was first discovered in a cluster of patients with severe respiratory symptoms in Hubei Province, China, in December 2019[1,2]. By early January 2020, analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid from infected patients revealed that COVID-19 is caused by the novel coronavirus strain, named the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[3], a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the beta genus coronavirus in the coronaviridae family.COVID-19 rapidly swept China and spread worldwide, becoming a global pandemic causing significant mortality and morbidity[4]. The current count of confirmed cases and deaths from COVID-19 worldwide can be found at the website of the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. At the time of this review (July 31, 2020),COVID-19 has caused more than 18 million cases and an estimate of more than 700000 associated deaths[5].

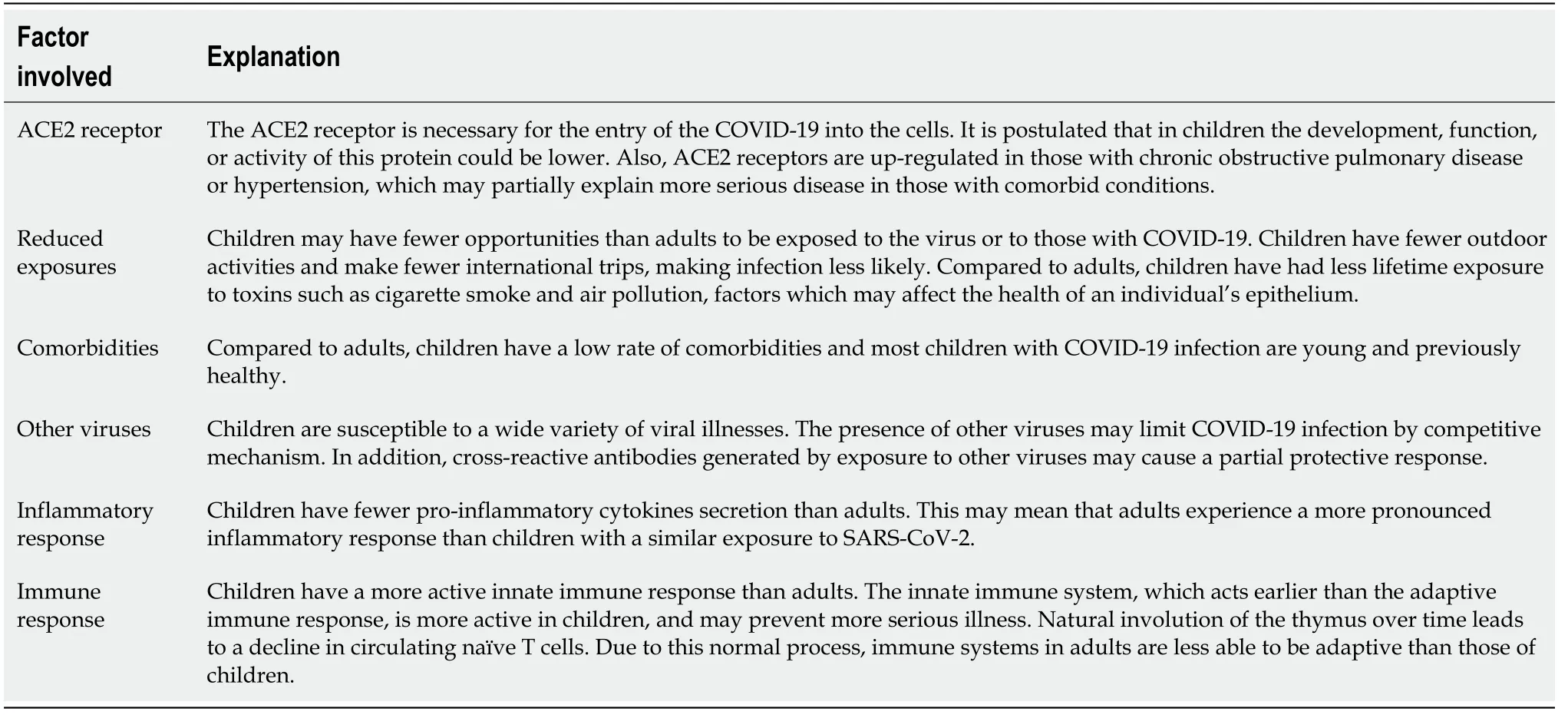

Since the beginning of the pandemic, COVID-19 in children has shown milder cases and a better prognosis than adults[6]. Children have worldwide so far accounted for approximately 2%-5% of diagnosed COVID-19 cases[7-14]. A review of 72314 patients by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention showed that only 1% of COVID-19 cases were in children younger than 10 years old[15]. Epidemiological studies have consistently demonstrated across the world that children are at a lower risk of developing severe symptoms or critical illness compared with adults. Donget al[16]reported, in the most extensive pediatric study in China, that only 5.2% had severe disease, while 0.6% had a critical illness, with a low case-fatality rate of less than 0.1%. In North America, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as of March 2020 found that 2% to 3% of pediatric patients with positive SARS-CoV-2 testing required hospitalization, with hospitalization rates for children of 0.3/100000 in patients aged 0 to 4 years and 0.1/100000 in patients aged 5 to 17 years. At the time of this publication, there had been relatively few reported cases of pediatric deaths attributed to COVID-19. In the United States the CDC reported a total of 121/391814 (0.03%) deaths associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection among persons aged < 21 years from February to July 2020. This supposed 121/190000(0.06%) of all reported death associated with COVID-19 in the same period. The median age of death in this age group was 16 years, with 30% of deaths occurring in children younger than 10 years old[17-21].DeBiasiet al[22]reported that 9/177(5%)cases of confirmed COVID-19 required pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission (no mortality) in Washington, DC Metropolitan region. Chaoet al[23]observed in New York City that 13/67 (28%) of pediatric COVID-19 cases required PICU admission with a mortality rate of 1.5%. Shekerdemianet al[24]reported that only 48 pediatric cases required PICU admission between March 14 and April 3, 2020, in 46 North American PICUs, with a mortality rate of 4%. Götzingeret al[25]in a multicenter (82 hospitals)cohort study, including 582 individuals with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection across 25 European countries, found that 363 (62%) individuals were admitted to hospital and 48 (8%) individuals required PICU admission. Only four children died(case-fatality rate 0.69%) suggesting that the case-fatality rate of COVID-19 in children is substantially lower than in older adult patients. The mechanism by which children seem less susceptible to severe infection caused by SARS-CoV-2 has yet to be elucidated (Table 1)[26-31].

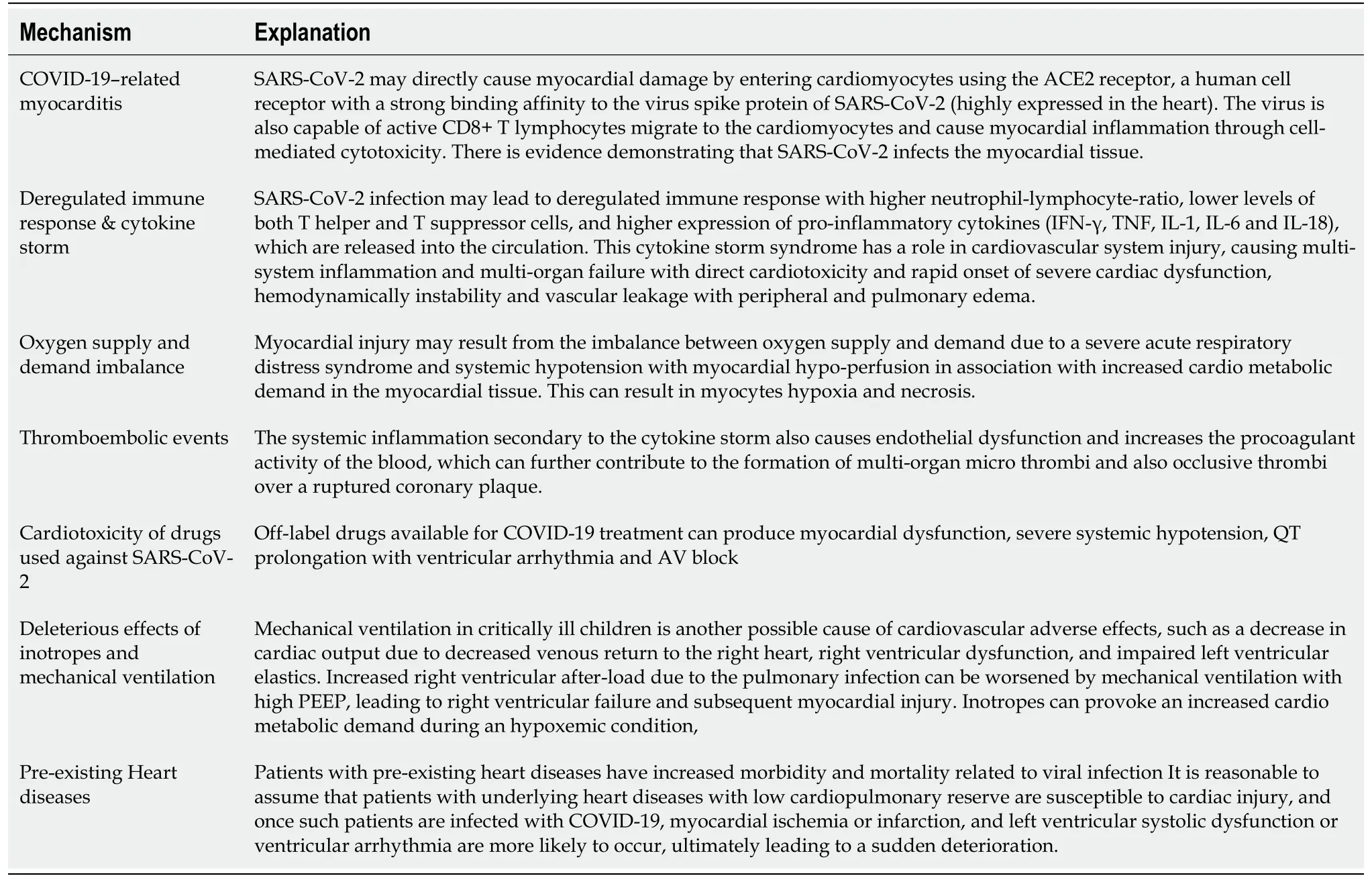

Clinical manifestations of COVID-19 in children overlap with many other pediatric viral infections. Most commonly, children presented with a mild flu-like state that can progress to potentially lethal acute respiratory distress syndrome, fulminant pneumonia, and multi-organ failure[10,32-35]. Although the respiratory tract is the primary target for SARS-CoV-2, the virus may interact with the cardiovascular system producing myocardial injury through different mechanisms (Table 2)[36-40], increasing morbidity in both, previously healthy patients and those with underlying cardiovascular conditions. Thus, cardiovascular involvement is emerging as one of the most significant and life-threatening complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults[41,42].

Given the smaller numbers of pediatric cases of COVID-19 regarding adults, there is still scarce data about the role of cardiovascular involvement in COVID-19 in children.Of note, up to 34% of children with COVID admitted to the PICU in Spain presented with signs of heart dysfunction[43]. Besides, there is a suggestion that, as with otherviral illnesses such as respiratory syncytial virus or influenza, children with underlying cardiac conditions are also at greater risk of cardiac complications or develop a more severe SARS-CoV-2 infection[21]. Furthermore, from April 2020,increasing cases of previously healthy children showing a hyper-inflammatory state and features similar to Kawasaki-Shock disease are being reported in Europe and America[44-49]. Remarkably, initial reports suggest many of these patients have myocardial dysfunction and coronary artery involvement with high requirements of PICU admission,hemodynamic,and respiratory support.All the above brings out that cardiovascular involvement could be a significant risk factor for severe COVID-19 in children. Thus, all health care providers must be aware of the potential impact of COVID-19 on children.

Table 1 Hypothesized mechanism for the lower susceptibility of children to coronavirus disease-2019

Table 2 Hypothesized pathophysiological mechanisms for cardiac injury in coronavirus disease-2019

In this article, we aimed to summarize the current knowledge about the potential cardiovascular involvement in pediatric COVID-19 to give a perspective on how to take care of them during the current pandemic emergency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A literature search was conducted by all the authors using PubMed and MEDLINE.Also, the websites of the health organizations including World Health Organization and CDC and the website of the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center were reviewed to provide up to date numbers and infection control recommendations.Multiple searches were performed during the writing of this article, as the COVID-19 pandemic is still evolving. Search terms “COVID-19” or “SARS-CoV-2" were used in combination with “myocardial injury” or "arrhythmia" or “cardiovascular involvement” or "heart disease" or "congenital heart disease" or “pulmonary hypertension” or "long QT" or “cardiomyopathies” or “channelopathies” or"Multisystem inflammatory system" or "PMIS" or “MIS-C” or ”Pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome" or "myocarditis" or "thromboembolism to identify publications from January 1st, 2020 until July 31st, 2020. Reference lists of the articles identified by this search strategy were reviewed to capture additional studies. No randomized trials neither interventional studies were available at the time this article was written; hence, observational studies, long-term prospective cohort studies, casecontrol, cross-sectional studies, case series, or case reports were also included in this review. Few additional articles before our search time period were included if they were referenced in existing articles and included pertinent essential data for this present article. Only articles published in the English language were included in this review. After the initial search, the authors separately screened all abstracts based on the eligibility criteria. Any abstracts or articles for which there was disagreement or uncertainty were reviewed again and discussed until consensus was reached. We finally included 193 articles. The included studies were categorized by whether the study involved previously healthy patients or patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions. As the vast majority of cases reported of pediatric cardiovascular involvement are patients with pediatric multisystemic inflammatory syndrome temporally (PMIS) associated with COVID-19, multiple meta-analyses were conducted to summarize the pooled mean proportion of different cardiovascular variables in this population. All the statistical analyses were performed using the STATA 14.0(StataCorp. College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

Most publications used in this review were single case reports, small case series, and observational small-sized studies or literature reviews. The most relevant articles were 16 studies with size > 10 patients and with complete data about cardiovascular involvement in children with PMIS, 10 articles reporting sporadic cases of myocarditis,pulmonary hypertension and cardiac arrythmias in previously healthy children, and another 10 studies reporting patients with pre-existing heart diseases. Most cases consisted in children with severe COVID-19 infection with full recovery after intensive care support, but cases of death were also identified. The management of the different cardiac conditions was extracted from the correspondent clinical guidelines or expert panel recommendations.

Cardiovascular involvement in children with COVID-19 but without a pre-existing heart disease

Pediatric multisystemic inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19:The incidence of severe COVID-19 in children is lower than in adults;however,Pediatric multisystemic inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PMIS) has been recognized worldwide over the past few months, changing the paradigm that children are not severely affected by SARS-CoV-2. Since April 2020,various alerts were issued in Italy, United Kingdom, and Spain about a local increase in the number of these cases[44-46].After these reports,the first cases in North America were reported in May 2020[47,48]. Recently, cases of PMIS are currently also diagnosed in Latinamerica[49]. In May 2020, case definitions for PMIS have been produced by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.K.’s Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, as well as by the World Health Organization(Table 3)[50-52]. Following these case definitions, 570 cases of PMIS have been notified to the CDC from March to July 2020[53]. Taking into account that on July 29th there were 4.5 million cases of COVID-19 and that children account for 2%-5% of these cases, the estimated incidence PMIS accounts for approximately 0.2%-0.6% of pediatric SARSCoV-2 infections. The case definition is nonspecific, and confirmatory laboratory testing does not exist. Therefore, it might be challenging to distinguish PMIS from other conditions with overlapping clinical manifestations such as severe acute COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease (KD), making challenging to know the exact incidence of the disease.

As the COVID-19 pandemic has evolved, case reports have appeared describing school-aged children and adolescents presenting with persistent high fever and systemic hyper-inflammation, reflected in a constellation of symptoms involving multiple organ systems[54-89]. They frequently manifested abdominal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms, KD-like features, myocardial dysfunction, coronary artery dilation, and cardiogenic shock. Most cases required PICU admission and inotropic support, with the rare need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).Almost all of these children wholly recovered in a few days, although rare deaths have been reported. These patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection either by nasopharyngeal reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay or by antibody testing. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that higher regional incidences of PMIS are associated with the larger COVID-19 outbreaks in the countries mentioned above, with most PMIS diagnoses occurring approximately four weeks after COVID-19 diagnoses peaks[80,83]. This temporal and spatial association suggests a causal link between SARS-CoV-2 and PMIS.

If PMIS is indeed related to infection with SARS-CoV-2, the pathophysiological mechanism of disease is unclear. PMIS is presumed to reflect a post-infectious cytokine-mediated hyper-inflammatory process, triggered by COVID-19 infection[89-95].Of note, there are striking similarities between the overall clinical picture of children affected by PMIS and the late phase of adult COVID-19 infection, characterized by cytokine storm, hyper-inflammation, and multi-organ damage[96-98]. Thus, they had laboratory findings associated with the cytokine storm described in adults, including high serum C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR),procalcitonin, ferritin, Dimer-D, interleukin (IL)-6, Troponin and pro B-type natriuretic peptide (proBNP) levels. These findings suggest similar pathogenesis and a spectrum of illness from children to adults, leading to the hypothesis that PMIS is due to a postinfectious inflammatory state that occurs several weeks after a primary infection with SARS-CoV-2. Accordingly, most of the patients with PIMS were positive for IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 (which typically appears 2-4 wk after primary infection)when the hyper-inflammatory symptoms appeared. Proposed mechanisms include direct triggering of auto-inflammatory response and deregulation of immune responses after COVID-19 infection, which could result in other environmental insults triggering a hyper-inflammatory pathology in predisposed patients[89-98]. One hypothesis for the marked cytokine storm experienced by children with PMIS derives from the ability of coronaviruses to block type I and type III interferon responses,which can lead to an uncontrolled viral replication in those with initially high SARSCoV-2 viral load[99]. Myocarditis has been demonstrated by late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in various children with PMIS[77]. Recently, the presence of viral particles of SARS-CoV-2 in different cell types of cardiac tissue in the autopsy of a PMIS case has been demonstrated[72]. This finding points out that SARS-CoV-2 could also produce a direct myocyte injury similar to other viral myocarditis as the mechanism of myocardial injury and heart failure during the PMIS course. Both the virus-induced damage and the local inflammatory response to cell injury could lead to necrosis of cardiomyocytes. The finding of viral particles in neutrophils within the myocardium supports the idea of local virusinduced inflammation. Of note, infection of endothelial cells in the endocardium could result in the hematogenous spread of SARS-CoV-2 to other organs and tissues,facilitating the typical multisystem failure.

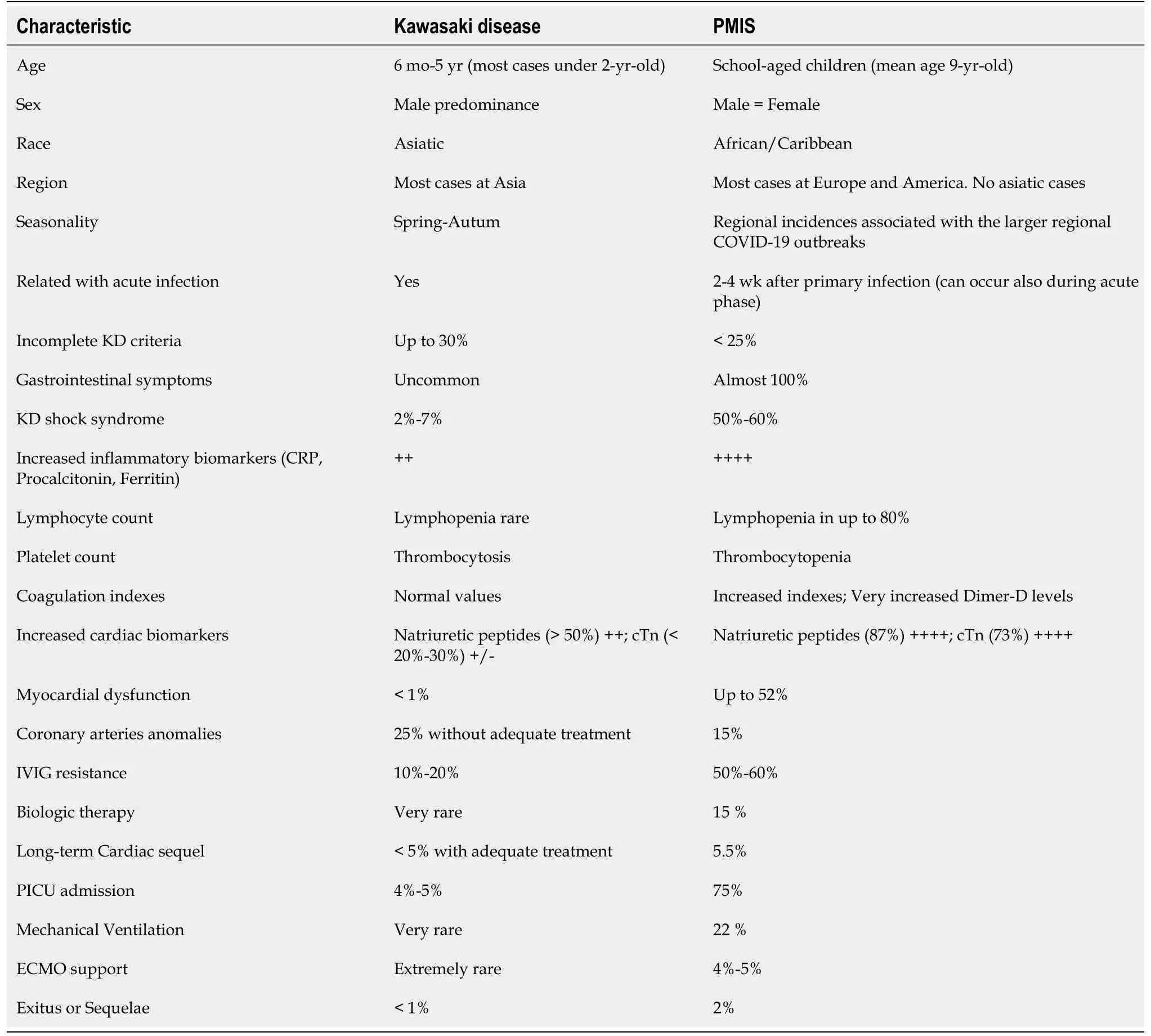

Currently, available data so far suggests that PMIS shares a common pathophysiological pathway and overlapping symptoms with that described inKD[100-106]. However, clinical, laboratory, and epidemiological characteristics of PMIS appear to be different from those of KD, raising the question if they are the same entities. As the outcomes are distinct and PMIS seems to be more aggressive, it is critical to make the subtle distinction between classical KD and PMIS. The absence of cases in Asia, the predisposition of Afro-Caribbean people, the older age of the patients, the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms in almost patients, the presence of lymphopenia/Leucopenia, the abnormal coagulation indexes, the higher levels of ferritin, D-dimer, inflammatory and cardiac markers, the higher rates of cardiogenic shock, myocardial dysfunction, PICU admission, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)resistance, the requirement of advanced respiratory or circulatory support and mortality could be the main differences (Table 4)[100-106].

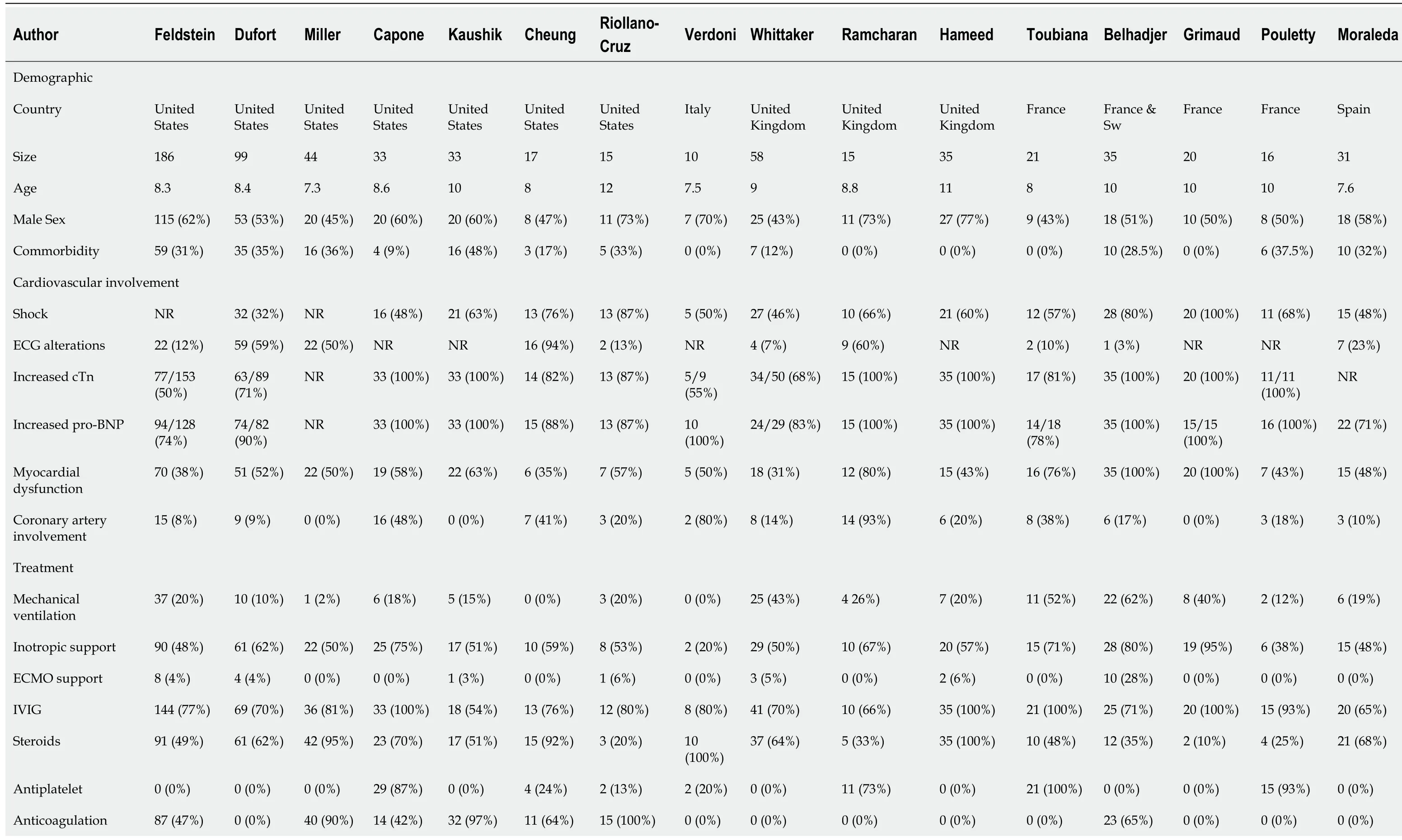

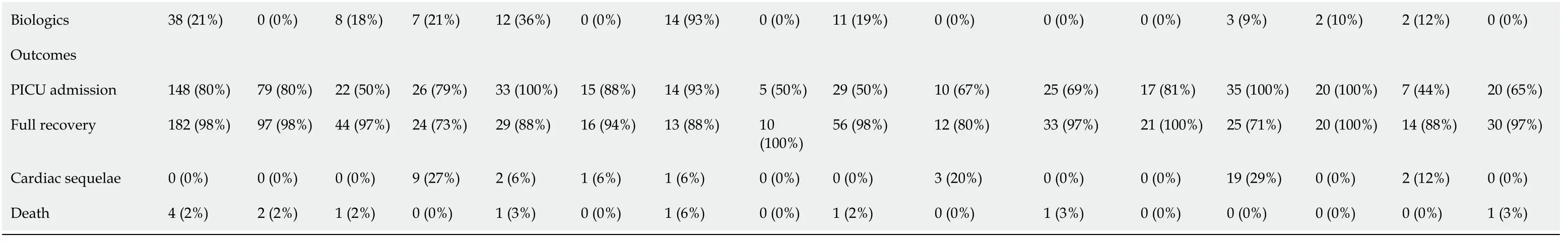

For this review we selected only those studies that included at least 10 patients with PMIS and with complete data about cardiovascular involvement (cardiogenic shock,cardiac biomarkers, ECG, echocardiography), treatment (inotropes, mechanical ventilation, ECMO support, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory) and outcomes[45-48,54,56,60-62,65,66,68,70,76,78,86]. We excluded those articles with suspected overlapping of patients due to multiple communications of the same patients in different papers. In our review, we found a total of 688 PMIS cases (56.8% male sex; mean age of 9 years)reported by 16 different authors from April to July 2020 across Europe and North America (Table 5, Figure 1). Of note, the vast majority of patients were previously healthy (74.4%), and the most common associated comorbidities observed were asthma and obesity, with a minimal prevalence of previous cardiac diseases. Since the first cases were reported, it was noticed that PMIS could be a severe acute condition,especially focusing on the cardiovascular system. Thus, the cardiac troponin and natriuretic peptides [N-terminal (NT)-proBNP or proBNP] were increased in most cases of PMIS (73.6% and 86.8% respectively). ECG alterations were not infrequent(27.6%), overall in the form of unspecific ST segment and T wave alterations,prolonged QT interval, and very few ventricular arrhythmia or AV blocks. However,there have also been reported cases of sustained arrhythmias leading to hemodynamic collapse and the need for ECMO support. Most important, as myocardial dysfunction and heart failure have been observed in up to 52%-53% of cases, PMIS must be bear in mind as a cause of new-onset heart failure in children during the pandemic. Also, and similar to KD, PMIS can lead to the development of coronary artery alterations (15%).Although infrequent, most of the cases of PMIS require hospitalization and intense clinical management because of the severity of the disease. Two recent multicenter studies in Spain reported that up to 31/252 (12%) of hospitalized children with COVID-19 and that 27/50 (54%) of cases that required PICU admission were diagnosed as PMIS[43,86].

Table 4 Differential characteristics between Kawasaki disease and the novel Pediatric Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection

In our review, we found that a PICU admission rate of 75.6%, with up to 56.4% of cases presenting with shock requiring inotropic support, and 4.3% requiring ECMO support. Conversely, only 22% of patients required mechanical ventilation, suggesting that the primary pulmonary involvement could not be a significant issue in PMIScases. Despite prolonged PICU admissions (mean PICU stay 4-7 d), the reported clinical outcomes for pediatric patients with PMIS appear favorable. Almost all patients (93.7%) presented a rapid full recovery within the first week of the disease.Most patients recovered when the severe inflammatory state associated with the SARS-CoV-2 infection is resolved. For this purpose, a high proportion of patients diagnosed as PMIS have been treated initially with IVIG (77.8%) and steroids (58%) in a similar way to KD[100-106].However, to resolve this severe inflammatory state associated is challenging, as these patients exhibit an increased resistance rate to these anti-inflammatory therapies regarding those rates reported for KD. Hence, biologic therapy blocking IL-1 (anakinra) and IL-6 (tocilizumab) receptors have been used in up to 14.5% of PMIS cases. COVID-19 prothrombotic effects are concerning in adults[107-110], increased use of anticoagulation (33.2%; mainly low weighted enoxaparin)and antiplatelet agents (12.5%; primarily aspirin) have been observed in these patients.Children with PMIS are at risk of thrombotic complications from multiple causes,including hypercoagulable state, possible endothelial injury, stasis from immobilization, ventricular dysfunction, and coronary artery aneurysms[111]. Therefore,antiplatelet and anticoagulation are recommended[112,113]. The low-rate of aspirin use could be explained by its prescription, especially in patients with KD-like clinical presentations (20%-25%), or in those with evidence of coronary involvement (15%).Cardiac sequelae in the form of mild myocardial dysfunction or coronary artery alterations were present in up to 5.5% of cases. Furthermore, although the case-fatality rate is known to be minimal in pediatric COVID-19, PMIS account for 15/121 (12%) of SARS-CoV-2 associated deaths among persons aged < 21 years in the United States from February 12th 2020 to July 31st 2020. Thus, we found a mortality rate of 1.8% in this review, which is higher than the 0.1%-0.6% mortality rate for pediatric COVID-19 reported before the emergence of PMIS.

Table 5 Summary of the data about cardiovascular involvement reported by the case series with more than 10 children with Pediatric Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome

Sw: Switzerland; cTn: Cardiac Troponin; BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide; ECMO: Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulin; PICU: Pediatric intensive care unit.

Figure 1 Forest plot that summarizes the pooled mean proportion of the cardiovascular characteristics of children with pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with coronavirus disease-2019. Multiple separate meta-analyses were conducted. Considering the high likelihood of between study variance, a random effects model was used. Continuity correction for total zero events studies was performed to include these in the meta-analysis as recommended. Pooled data were presented with 95%CI and displayed using forest plots. Heterogeneity within studies was assessed using I2 statistics. For all the factors analyzed, the P value for heterogeneity was determined to be > 0.10 and the I2 values were < 50% (adequate heterogeneity between studies).

As the prognosis is excellent after treatment, the early diagnosis of PMIS and prompt initiation of anti-inflammatory therapy is crucial for a successful, rapid, and full recovery and preventing end-organ damage and mortality. For this purpose, a high index of clinical suspicion is needed. As cardiovascular involvement is present in any form in almost patients with PMIS, the screening of cardiac alterations through cardiac biomarkers, ECG, or echocardiography could be useful for the early identification of PMIS cases. Data from this review indicate that PMIS cases have similar manifestations and outcomes from different studies across the world.Therefore, there are arguments to consider PMIS a new syndrome with a strong link with SARS-CoV-2 infection. As fundamental aspects of PIMS remain unknown, future studies will improve prospects for the prevention and treatment of this severe pediatric condition. Until them, a close multidisciplinary collaboration among various disciplines including pediatrics, intensive care, rheumatology, cardiology, and immunology is warranted for the adequate management of these patients.

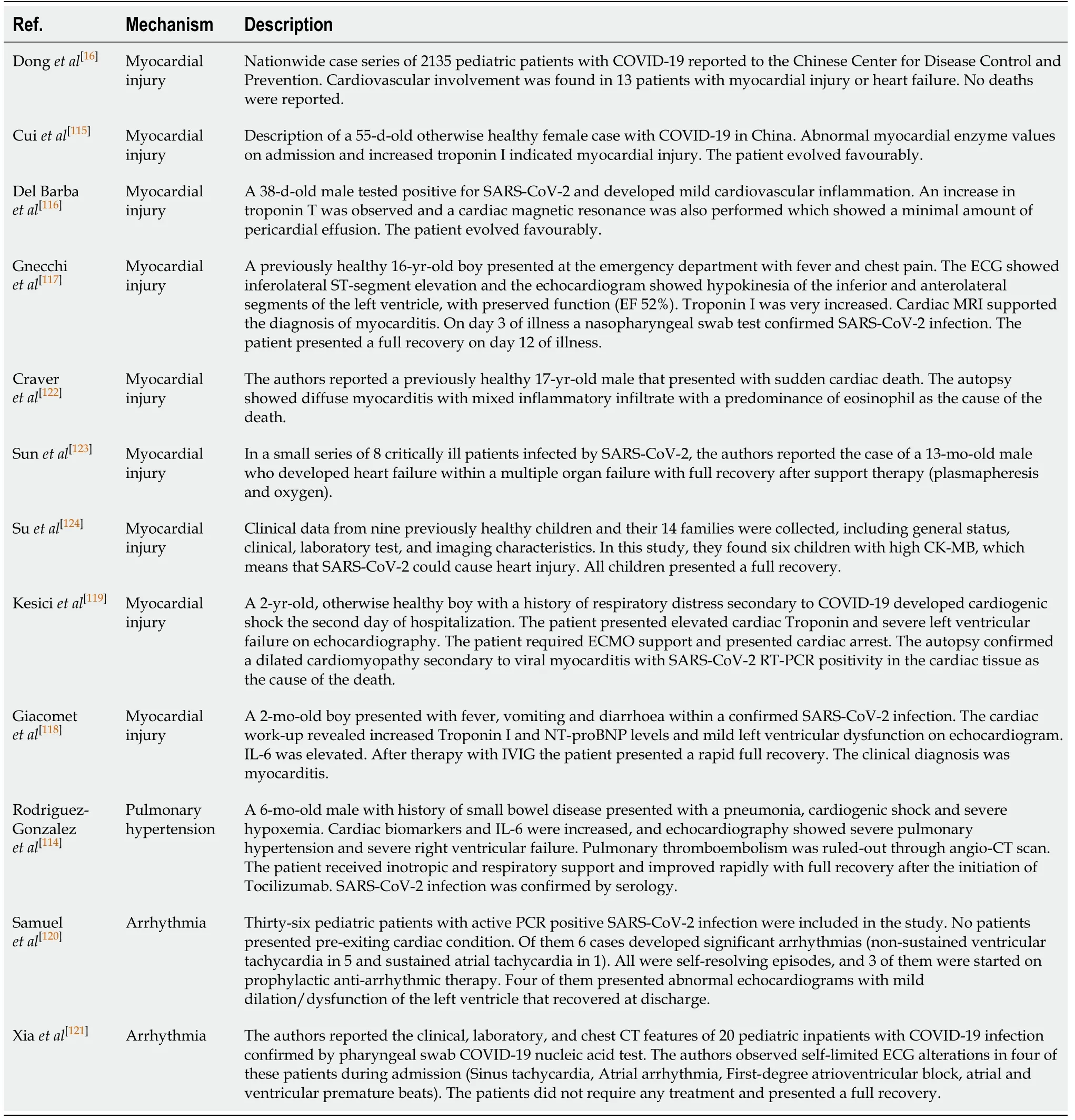

Cardiovascular involvement in previously healthy children out of PMIS:There is also evidence of cardiac manifestation in previously healthy children out of the setting of PMIS in children. Since the beginning of the pandemic, a few cases have been reported with cardiovascular involvement similar to adults, in the form of myocarditis, pericarditis, heart failure, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrhythmia, and pulmonary hypertension (PH) (Table 6)[114-124]. Although infrequent, these cases are usually reported as severe or critically ill patients, pointing out the relevance of the cardiac involvement also in previously healthy children with COVID-19.

Myocardial dysfunction and heart failure:Myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the myocardium, diagnosed by established histological, immunological, and immunehistochemical criteria, caused mostly by infectious, immune-mediated or toxic agents[125]. Remarkably, SARS-CoV-2 may represent another viral etiology of myocarditis. Acute myocardial injury by SARS-CoV-2 may be due to the coincidenceof various mechanisms including a direct viral myocardial injury, a secondary inflammatory response in the form of cytokine storm, the severe hypoxemia due to pneumonia, and the side-effects of therapy against SARS-CoV-2 infection (Table 1 and 2)[126-129].

Table 6 Description of the case or case series of cardiac involvement in pediatric patients without pre-existing cardiac condition and coronavirus disease-2019

To date, sporadic cases of myocarditis have been reported in pediatric COVID-19 patients as the first clinical presentation of the disease, alone or in the clinical context of pneumonia. Donget al[16]found myocardial injury and heart failure occurring in up to 0.6% (13/2135) of pediatric patients with COVID-19 reported to the Chinese Center for Control and Prevention. In the following months, more sporadic cases have been reported around the world[115-124,130,131]. The myocardial injury affected all age ranges,from neonates to adolescents, and a not low number of these children presented in an unexpected form of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection with increased morbidity (PICU admission, inotropic support, mechanical ventilation…) and mortality, including cases of sudden cardiac death.Of note,the presence of viral particles of SARS-CoV-2 in the myocardium of children with sudden cardiac death reinforces the direct viral damage as one of the main mechanisms of myocardial injury in healthy children[72]. Based on the few published data, SARS-CoV-2 may represent a potential novel etiology of fulminant myocarditis, which it should be suspected in COVID-19 patients with acuteonset chest pain, ST-segment changes, cardiac arrhythmias and hemodynamic unstability[131,132]. Also, left ventricular dilatation, left ventricular hypo-contractility (on echocardiography), and a significant increase in cardiac troponin and proBNP levels could also be present. Myocarditis seems to be a rare event in pediatric COVID-19, but when occurred, appears early in patients’ clinical history and could lead to sudden cardiac death. However, as few studies described myocardial injuries in these COVID-19 patients, the impact on clinical prognosis needs to be clarified in this population.

Pulmonary hypertension secondary to the primary pulmonary infection or PTE:Right heart failure with increased pulmonary vascular resistance and PH should also be considered as a possible cardiac manifestation in previously healthy children,especially in the context of moderate-severe pneumonia with acute respiratory distress syndrome and hypoxemia[132]. PH is a well-known complication of pulmonary viral infections leading to adverse outcomes when present, also in the COVID-19 scenario[114,133-136]. Interestingly, nonetheless, concomitant pneumonia, PH has not been reported as one of the main characteristic of the disease in children. Thus, we only found one case of severe PH and right ventricular failure secondary to a severe pulmonary infection in our literature review[114]. In this case, the increased levels of cardiac troponin and proBNP prompted an echocardiogram realization that diagnosed severe PH. Previous cases reported of severe pulmonary hypertension in adults were secondary to pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), but no cases of massive PTE have been demonstrated in children[137-139]. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that the pulmonary endothelial cell damage leading to the endothelium, the activation of coagulation pathways, and deregulated inflammatory cell infiltration with cytokine storm could be the primary physiopathological mechanism of the severe PH observed in these patients[88-91,140]. Small segmental pulmonary emboli (PE) have been observed in some pediatric patients affected by PMIS supporting this theory[141-143], but the clinical significance of these findings is still unclear. Finally, pulmonary artery vasoconstriction due to severe hypoxemia and respiratory acidosis may act as a coadjuvant factor for the development of PH[144,145].

Cardiac arrhythmia in healthy children:There are little data about the occurrence of arrhythmias in the context of pediatric COVID-19. Data from 2 small-sized studies showed that hospitalized pediatric COVID-19 cases could present a rate of cardiac arrhythmia as high as 16%-20%[120,121]. Initial data from Chinese observations suggest that contrary to adult patients, whose myocardial involvement is sometimes correlated with the appearance of life-threatening arrhythmias, children with COVID-19 share less harmful rhythm troubles, such as supraventricular tachycardia, premature atrial and ventricular complexes, first-degree atrioventricular blocks, and incomplete right bundle branch block[16,36,121]. Recently, Samuelet al[120]observed non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in 5/6 patients that developed cardiac arrhythmia in a case series of 36 children. Although all were self-resolving episodes, up to 50% of cases required the initiation of antiarrhythmic drugs. Based on these few data, arrhythmias represent a not rare clinical presentation of COVID-19, which could complicate the clinical course of disease during hospitalization and worsen the prognosis of infected patients. For this reason, careful electrocardiographic monitoring should be performed in COVID19 patients to early detect paroxysmal arrhythmia that does not match the disease status and might be a red flag of worsening disease.

Ventricular arrhythmias seem to be directly correlated to the COVID-19 induced myocardial injury. Accordingly, a higher incidence of ventricular arrhythmia was reported in adult patients with elevated troponin-T levels[37-42]. Notably, 4 of 5 of the cases of ventricular arrhythmia reported by Samuelet al[120], presented abnormal echocardiograms with mild dilation/dysfunction of the left ventricle. Furthermore,ventricular fibrillation has been documented in some cases of fulminant myocarditis and sudden cardiac death in children[117-119,122]. Therefore, the direct myocardial injury seems to be a determinant factor for arrhythmia also in children. Hypoxemia and electrolyte unbalance are not rare in the acute phase of severe COVID-19 and can also trigger cardiac arrhythmias[146]. The potential role of pharmacological treatments such as hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and azithromycin in enhancing the susceptibility to QTrelated life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, particularly Torsades de pointes(TdP), is increasingly recognized in adults[147-149]. Nevertheless, pediatric observations have shown that these drugs are safe in previously healthy children[150].

The characteristic hyper-inflammatory systemic state of COVID-19 has been proposed as a potentially crucial pro-arrhythmic factor. This fact is supported by the occurrence of arrhythmic events in PMIS cases mentioned above. Strong evidence from basic and clinical studies points to pro-inflammatory cytokines, mainly IL-6, as a novel and essential risk factor for long QT-syndrome and TdP[151-153]. Systemic inflammation might additionally predispose to long QT-syndrome/Td as a result of indirect mechanisms, such as the induction of cardiac sympathetic system hyperactivation and the inhibition of cytochrome p450, particularly CYP3A4, leading to an increased bioavailability of several medications, including QT-prolonging drugs.

The coexistence of myocardial injury and cardiac arrhythmias with COVID-19 makes it challenging the diagnosis and management of this entity. The early recognition of cardiac symptoms and their timely treatment may be of pivotal importance to improve the prognosis of pediatric patients, overall in those with severe disease.

COVID-19 in children with pre-existing heart disease

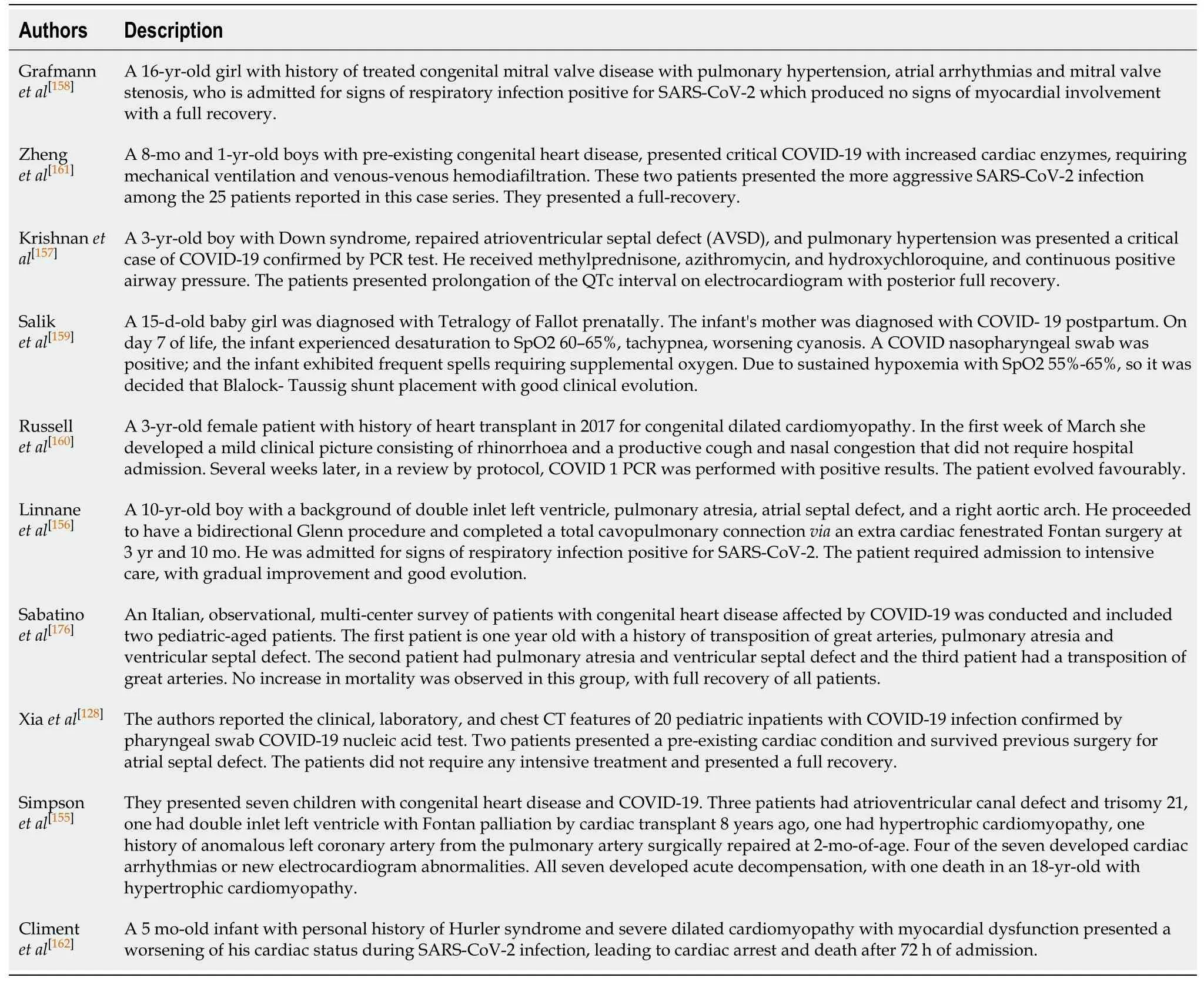

Congenital heart diseases:Congenital heart diseases (CHD) affects approximately up to 8/1000 (0.8%) newborns and remains the leading cause of infant mortality due to congenital malformations[154]. Currently, there are no reliable data with regards to the burden of infected children with CHD and the COVID-19 related morbidity and mortality in this setting. Few studies are focusing on children with CHD and COVID-19, mainly limited to sporadic case reports or small case series (Table 7)[155-162].These children seem to be a vulnerable population to a potential clinical deterioration in the presence of bilateral pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by SARS-CoV-2, especially those with non-corrected complex cardiac defects and decreased cardiopulmonary functional reserve. Furthermore, even patients with corrected CHD can present with relevant residual lesions such as residual valvular or shunt lesions, ventricular dysfunction, heart failure, arrhythmias, pulmonary vascular disease, or cyanosis. Apart from the hemodynamic burden, some of these children might have associated comorbidities such as lung disease, liver impairment, renal failure, neurological sequelae, and impaired immunity associated with possible concomitant syndromes (Down syndrome, DiGeorge syndrome, heterotaxy syndromes with asplenia). Due to the documented myocardial involvement of SARSCoV-2 infection in both adults and children, and the increased mortality observed in adult patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease and pediatric CHD with other viral infections (Influenza and respiratory syncytial virus)[163-166], there is a possibility that SARS-CoV-2 infection may produce new-onset of cardiac complications or a worsening of the basal status in this vulnerable population. It is essential to bear in mind that, as in other viral respiratory infections, it can be challenging to differentiate pneumonia from cardiac complications in these children due to an overlapping presentation. For example, children with non-cyanotic CHD with increased pulmonary blood flow have higher than standard resting respiratory rates even in a basal state, and some signs of respiratory distress can be secondary to heart failure.Children with cyanotic CHD have low baseline saturation (< 92%) and cyanosis due to their cardiac pathology. Due to these reasons, delayed diagnosis and treatment of critical cardiac complications could also increase morbidity and mortality.

Children with underlying medical conditions represent 25% of the total pediatric COVID-19 cases and 80% of those hospitalized. Hoanget al[167], in an early systematic review including 7780 pediatric COVID-19 cases form 26 different countries, found that a pre-existing cardiovascular condition was present in up to 14% of patients. In the United States the CDC established on 6 April 2020 that chronic lung disease(including asthma) is the most prevalent preexisting condition (50%), followed by cardiovascular disease (31%; including obesity) and immunosuppression (12.5%).Regarding the mortality rate associated with pre-existing conditions, the CDC reported 121 deaths among persons younger than 21 years old in the United States from February to July 2020. Of them, only 25% were previously healthy people.The most frequently reported medical underlying conditions were chronic lung disease (28% including asthma), obesity (27%), neurologic conditions (22%) and cardiovascular conditions (18%). However, these reports did not analyze the association with outcomes. To date, only one multicenter observational study that only included 2 pediatric cases has focused on the clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with CHD infected by SARS-CoV-2. The authors found that of the 76 patients included, cardiovascular complications were mainly found in the CHD-COVID-19group, but they did not observe the worst outcome in this population[167]. An early systematic review by Sannaet al[36], including only the Chinese experience, concluded that the presence of CHD is a high-risk factor for severe COVID 19 in children.Götzingeret al[25], in a multicenter cohort study that involved 25 European countries and included 582 children, found that 25% of pediatric COVID-19 cases presented preexisting medical conditions, which resulted in an independent risk factor for PICU admission (OR, 5.06, 95%CI: 1.72-14.87;P= 0.0035) in multivariate analysis. Of note, a total of 25 (4%) children had a previously known CHD as comorbidity, and they present a higher risk for PICU admission (OR, 2.9, 95%CI: 1.0-8.4;P= 0.029) in the univariate analysis. DeBiasiet al[22]reported a cohort of 177 children with COVID-19 in the United States. Of them, 3% presented a pre-existing cardiac condition, and these patients were more common in hospitalized as a non-hospitalized group (9%vs1%;P= 0.004). However, when comparing the SARS-CoV-2 infected non-critically ill and critically ill hospitalized patients, there were no significant differences in the presence of underlying cardiac conditions (22%vs6%;P= 0.180).

Table 7 Description of the case or case series of cardiac involvement in pediatric patients with pre-existing cardiac condition and coronavirus disease-2019

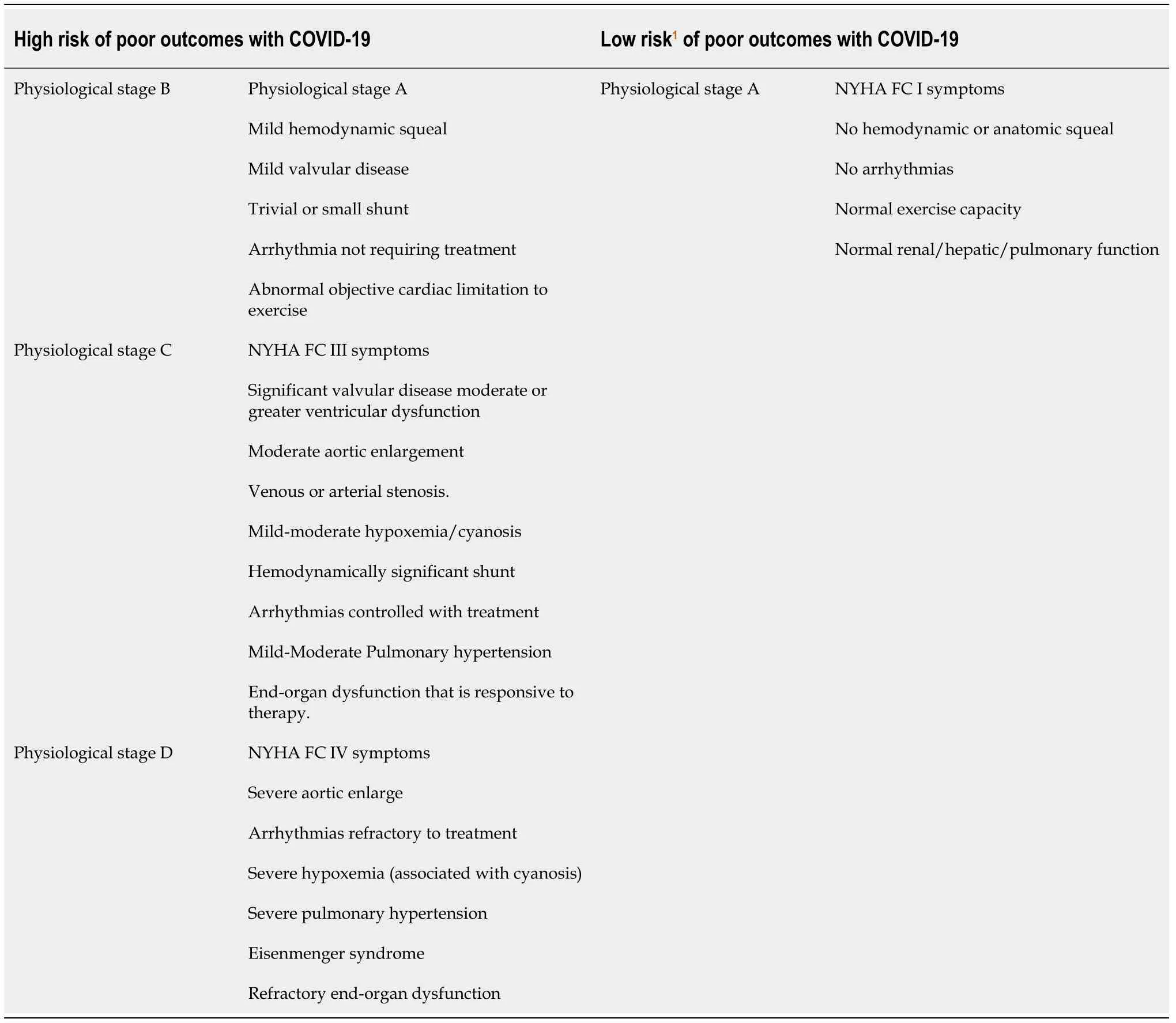

From these data, we can state that although plausible, there is not yet enough evidence currently to support the association of CHD and severe COVID-19 in children. It is necessary to bear in mind that these data could instead be a reflection of the overprotective management that is usually given to these patients, with preventive hospitalizations for monitoring even though they do not require treatment, nor do they have severe clinical affectations. Hence, using recommended clinical criteria for hospital admission in children with CHD might lead to many of these being hospitalized, who could otherwise have been managed at home[12]. Remarkably, the admission of these high-risk patients must be overweighted with the risk for SARSCoV-2 nosocomial infection, and the presence of CHD should not be used in isolation for hospitalization. CHD constitutes a very heterogeneous group of patients and not all the CHD have the same risk for adverse outcomes during viral infections.Therefore, the identification of vulnerable CHD cases is crucial to improve the efficiency of the management of this population, avoiding unnecessary hospitalizations and also the late recognition of life-threatening complications in this population. In the absence of strong pediatric evidence, risk stratification, and further recommendations are currently performed based on the adult CHD anatomic and physiological classification (Table 8)[168]. In summary, any child with a CHD requiring medication for heart failure or arrhythmia may experience a worsening of their clinical status because of the hemodynamic impact of the lung involvement and the myocardial injury of SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the other hand, children with complete and successful surgical correction of the CHD and without the need for cardiac medications could be managed as healthy children. This approach requires individual assessment and adjustment for consistency with current local recommendations. The specialized evaluation by the pediatric cardiology team could be essential for the adequate selection of cases that will benefit from hospitalization and more therapies than supplemental oxygen, such as heart failure drugs.

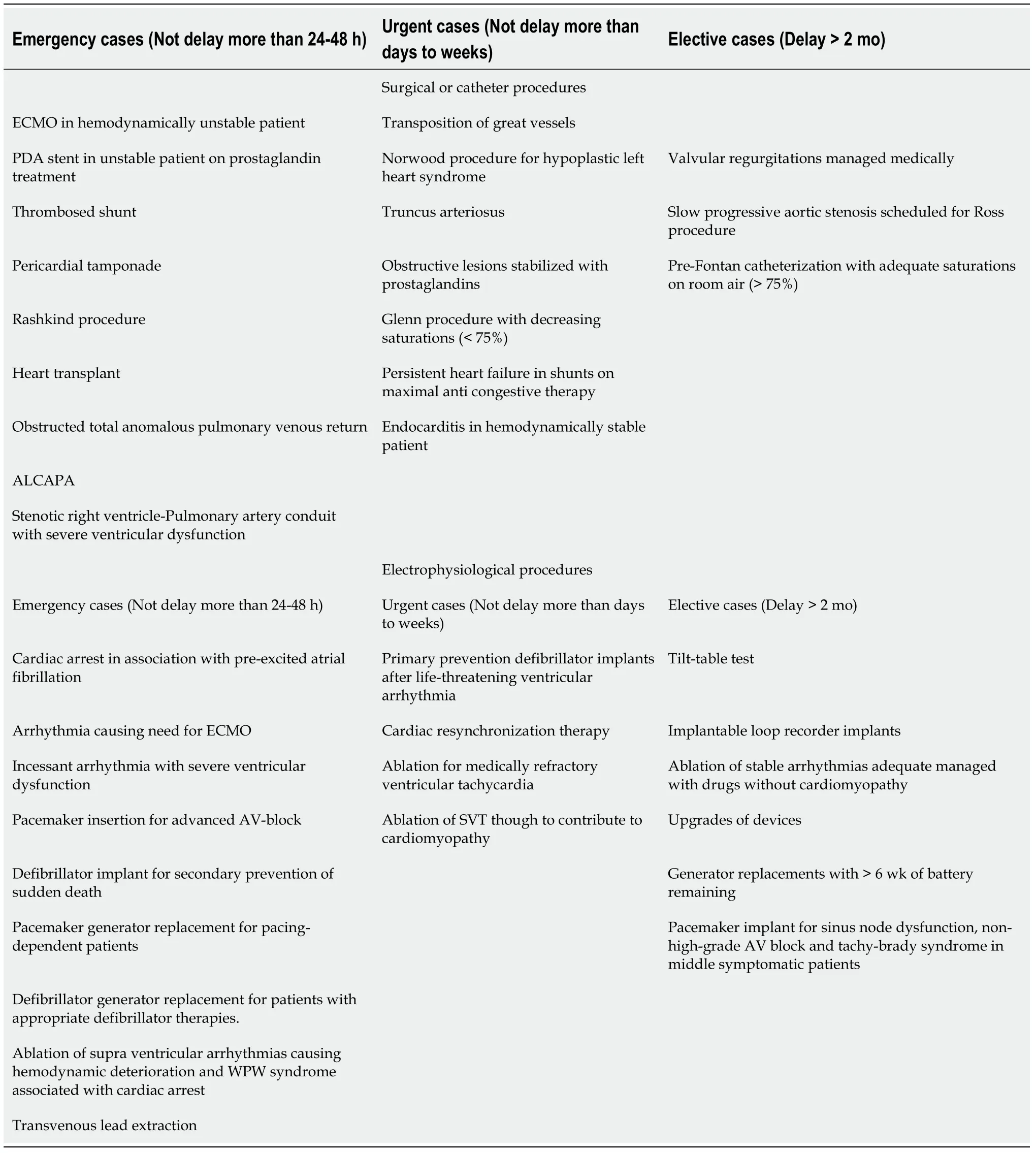

In addition to the increased risk for severe infection, CHD patients are facing the tremendous impact of the pandemic on outpatient visits and surgical programs around the world[169-172]. To minimize SARS-CoV-2 spread, extensive preventive measures are essential for these patients. Similar to the general population, children with CHD and their careers must adopt physical and social distancing measures,meticulous hygiene with frequent hand washing, and use appropriately of facemasks.Nevertheless, social distancing can be particularly challenging for pediatric CHD patients, especially newborns and infants, who are a fragile population in need of immediate and continuing care. Due to the declared lockout to restrict physical contact, the many sick leaves for healthcare professionals, and the reallocation of CHD specialists to general care facilities to deal with these sick leaves, the volume of CHD outpatient visits may have to be reduced to essential visits only. Likewise, a profound reorganization with prioritization of emergent and urgent procedures, and the cessation of all-elective surgical activity has been adopted (Table 9). Therefore, there is an expanding increase of the waiting lists, leading to a delay of the diagnosis and adequate management of CHD complications and a delay of the optimal timings for corrections of some stable CHD, with a potential direct effect on morbidity and mortality. This problem is particularly significant in newborns and infants, who are a fragile population in need of close and continuing care and often require surgery during a narrow window of time to avoid death and provide for optimal outcomes. To avoid preventable complications due to canceled visits and diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, pediatric cardiology specialists should review outpatient appointments and ensure that high-risk patients are prioritized. For most patients listed on class IA,scheduled clinic visits should be converted to telehealth visits whenever possible, to maintain social distancing to avoid disease spread[173,174]. However, pediatric cardiology teleservices could be not enough for complex chronic conditions. In these patients, the risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure must be weighed against the needful in-person visits case-by-case. It is still unclear the real impact of this reorganization in terms of increased morbidity and mortality in this population. Of note, it would be essential to catching up with all surgical interventions and outpatient visits deferred during the pandemic at the same time that timely diagnosis and surgical corrections of all new patients are being carried out.

Genetic heart diseases:Genetic heart diseases (GHD) represent a very heterogeneous group of congenital disorders affecting the heart muscle (cardiomyopathies) or the electrical system (channelopathies). Of them, the most prevalent conditions in children are long QT syndrome (LQTS), catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia(CPVT), Brugada syndrome, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)[175]. These rare conditions are often the underlying cause of life-threatening arrhythmias, myocardial dysfunction, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death in children and adolescents. The role of SARS-CoV-2 infection in these diseases is still not well known. The experience with COVID-19 in these patients is even scarcer than the existent of CHD patients. To date, we only have found 1 case report of a 5-mo-old infant with a personal history of DCM that presented a worsening of his cardiac status during SARS-CoV-2 infection, leading to cardiac arrest and death(Table 7)[162]. Also, a case of Brugada syndrome uncovered by fever has been reported in the adult population[176].

Table 8 Classification of Congenital heart diseases regarding the risk of severe coronavirus disease-2019 based on their anatomical and physiological characteristics

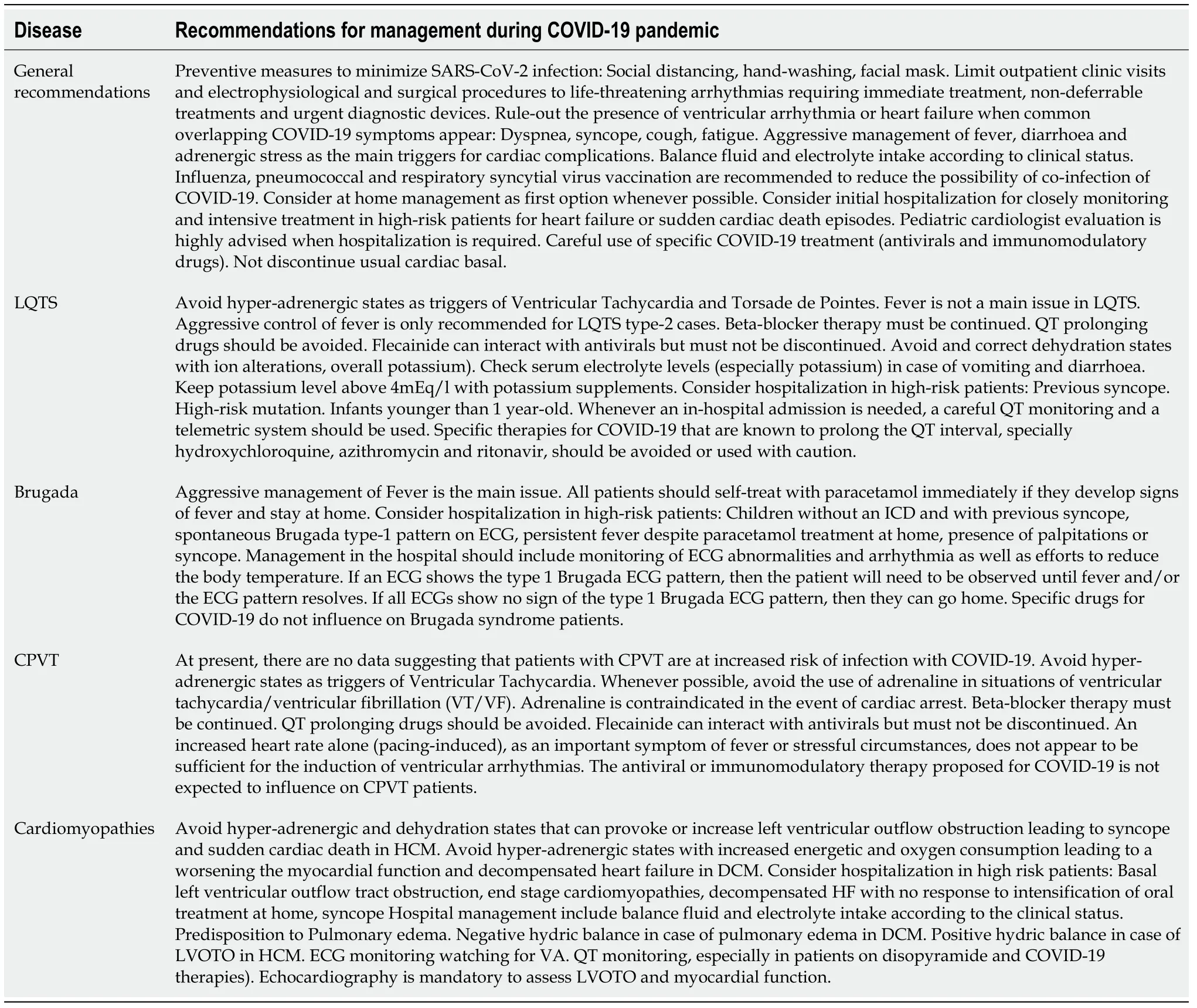

As mentioned above, SARS-CoV-2 infection can produce myocardial dysfunction and ventricular arrhythmia through direct myocardial damage and hyperinflammatory state. Also, as a viral infection, COVID-19 can provoke situations that can act as triggers for myocardial dysfunction and ventricular arrhythmias such as fever, hyper-adrenergic states, increased energetic and oxygen consumption,dehydration, ion alterations (especially potassium, calcium, and magnesium),metabolic crises with lactic acidosis… Finally, some drugs used against SARS-CoV-2(hydroxychloroquine, Remdesivir, azithromycin, tocilizumab) could be deleterious[177-180]. Therefore, patients with genetic heart diseases may be at an increased risk in the setting of COVID-19, necessitating additional precautions, and specialized management. As a very heterogeneous group, disease-specific recommendations and precautions should be employed. In the absence of enough evidence,recommendations for the management of these rare diseases are based on previous experience with other viral infections and following expert panel recommendations(Table 10)[181,182]. For example, fever must be managed aggressively in Brugada syndrome; potassium levels must be higher than expected in the case of LQTS.Situations of dehydration can be dangerous in the context of hypertrophiccardiomyopathy. In the case of DCM, there is an increased risk of metabolic decompensation or lactic acidosis with associated severe myocardial dysfunction. The increased adrenergic tone may be harmful in almost all cases, overall HCM, LQTS, and CPVT. Finally, Covid-19 infection in patients with cardiomyopathies represents a substantial risk of worsening patient clinical status, particularly in those who experienced previous heart failure, arrhythmic events, or myocardial dysfunction on echocardiography requiring medications.

Table 9 Classification of surgical and catheter-based procedures based on their relevance for the prognosis of the patients with congenital heart diseases and genetic heart diseases

Patients with GHD are suitable for multiple outpatient clinic visits, hospitalizations,and surgical or electrophysiological interventions to have the reasonable control of the disease. During the pandemic, similarly to those patients with CHD, only urgentsurgical procedures and electrophysiological studies are performed, delaying all elective procedures (Table 9) following expert panel recommendations[181,182]. When possible, most patients should at first be offered telehealth consultation, outpatient clinic visits must be warranted for all the new patients with a history likely of a lifethreatening condition and the follow-up of patients with known genetic heart disease when treatment cannot be optimized remotely. Patients with high-risk GHD and SARS-CoV-2 infection could benefit from hospitalization for close monitoring and management of cardiovascular complications. Again, expert evaluation of a pediatric cardiologist may be essential in determining how best to minimize the risk of cardiac events during hospitalization.

Table 10 Recommendations for the management of pediatric cases of genetic heart diseases during coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic

Issues with cardiac medication during SARS-CoV-2 infection:Many children with underlying heart diseases are under treatment with cardiac medications during the pandemic. Concern exists about the potential risks of deleterious effects of these drugs when they are administered during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Anti-inflammatory drugs(Aspirin, Ibuprofen, colchicine, steroids) are used in cases of pericarditis and KD[102,183,184]. They have been widely used in a safe and effective way in the treatment of PMIS cases. Beta-blockers are commonly used in pediatric cardiology, mainly as a treatment for heart failure in CHD or DCM, minimizing left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in HCM patients, and preventing VT in LQTS and CPVT. Amiodarone,sotalol, and flecainide do have interactions with other QT interval-prolonging drugs such as ritonavir/Lopinavir and chloroquine but is an important enough therapy not to discontinue in these particularly stressful circumstances where paroxysms of tachycardia could occur[185]. Digoxin and diuretics should be used cautiously. Digoxin action depends on potassium/calcium levels and toxicity may occur in case of vomiting or diarrhea during COVID-19. Diuretics can provoke alterations on the electrolyte imbalance and dehydration with deleterious effects for some patients[186]. As there is no evidence for the harmful effects of most of these drugs in the setting of COVID-19, the general recommendation is to continue on these medications unless contraindications or side effects appear.

Only the safety of Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors has been questioned early after the beginning of the pandemic. RAAS is widely used in children with CHD and heart failure as an agent to minimize afterload and avoid the abnormal myocardial remodulation[185,186]. It has been argued that RAAS inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may up-regulate of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2(ACE2), hereby increasing susceptibility to the virus and hence may cause a more severe infection[40-42,187]. Anyway, treatment with RAAS inhibitors may down-regulate the expression of ACE2, but it seems not to have a significant effect on its activity.Thus, the data is currently insufficient to provide any definitive recommendation to discontinue these medications in children taking them for indications for which the agents are known to be beneficial. Therefore, the leading international cardiovascular scientific societies recommend maintaining or initiating the ACEIs/ARB's treatment in patients with heart diseases when indicated, irrespective of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Cardiovascular effects of drugs used for COVID-19 treatment:Once a patient with underlying cardiac disease is diagnosed with COVID-19, the management of the infection is similar to the general population, with a particular focus in the surveillance of clinical signs of heart failure and ventricular arrhythmia. Currently, the primary treatment for COVID-19 disease is supportive care, ensuring adequate oxygenation,symptomatic relief with antipyretics, and nutritional support for the patient[12,188,189].Most children can be managed conservatively and do not require specific treatment. In the case of cardiovascular complications, the management should be done following current guidelines and local protocols for each manifestation. In severe cases of COVID-19, specific treatment with antiviral drugs (lopinavir/ritonavir,chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine) to control viral replication at early stages or immunomodulatory drugs (steroids or tocilizumab) to control the hyper-inflammatory response at later stages of the disease may be considered[190]. However, these drugs are not considered the standard of care at this point. They are mostly off-label and investigational drugs with only positive pre-clinical data. Of note, many specific COVID-19 therapies have potential cardiovascular side effects, which can further increase the risk of myocardial dysfunction and arrhythmias associated with SARSCoV-2 infection (Table 11).

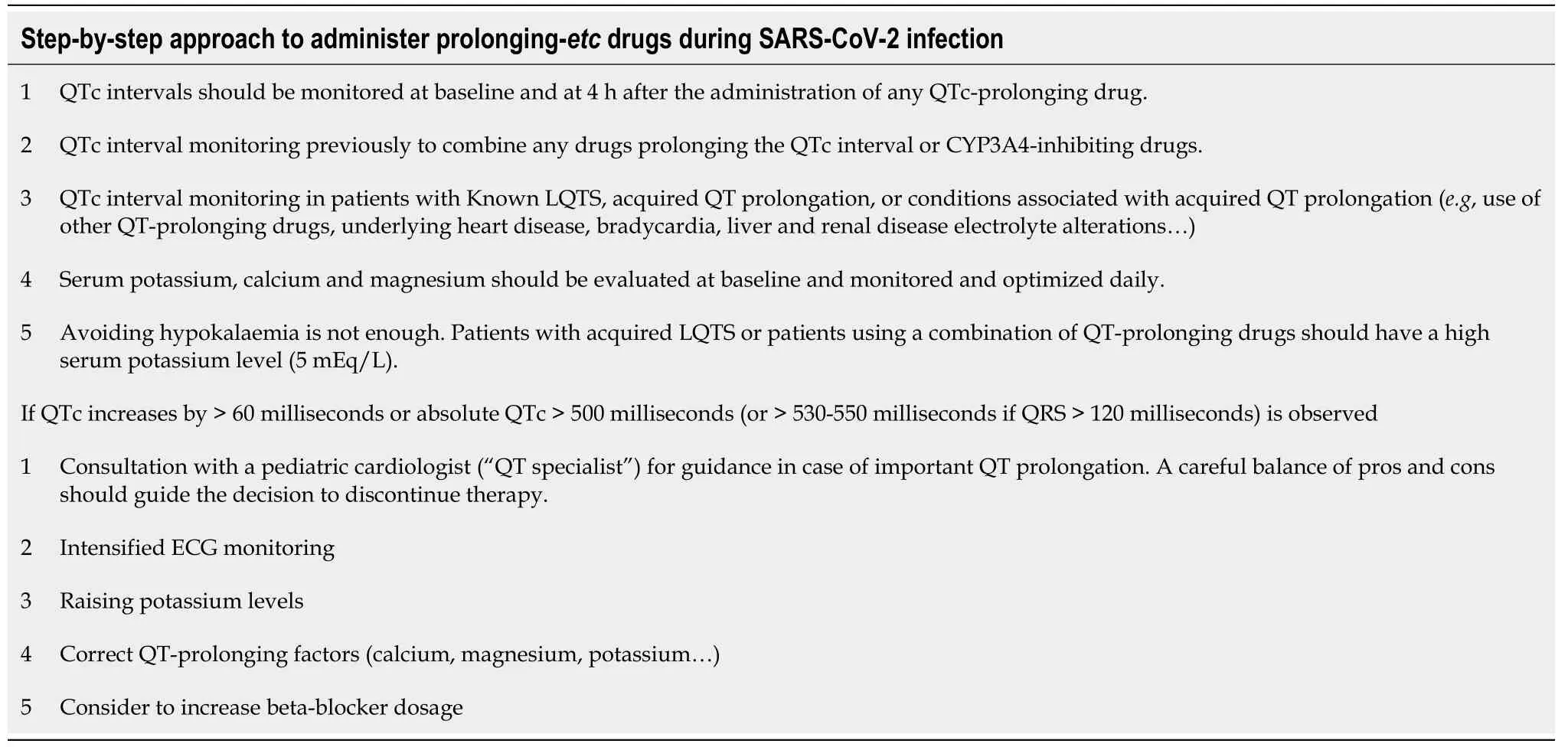

Early in the pandemic, concerns have appeared about the potential of proarrhythmic events due to the use of prolonging-qt drugs that have raised, particularly the combined use of chloroquine (CQ), HCQ and azithromycin[147-149,191,192]. The authors of a small single-center, the retrospective study found no risk of QT prolongation or TdP in children with COVID-19 under treatment with HCQ[150]. However, the patients included were not severely affected by the disease, and none of them required intensive care, had cardiovascular comorbidity, and were taking corrected QTprolonging medications, nor had ionic alterations. Therefore, caution must be used when applying them to patients with pre-existing heart disease. In the absence of clear benefit and safety data, therapies associated with greater QT prolongation and arrhythmic risk should be avoided, particularly if they are administered in combination with CYP3A4-inhibiting drugs. If they are considered to be beneficial, a step-by-step approach with the specialized supervision of the pediatric cardiology team must be made to minimize the occurrence of cardiac toxicity (Table 12)[193].

DISCUSSION

In this review, we have summarized the actual evidence about the cardiovascular involvement in children with COVID-19. Although respiratory illness is the dominant clinical manifestation of COVID-19, cardiovascular issues are emerging as one of the most significant complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pediatric patients. As described above, patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases and with PMIS accounted respectively for 18% and 12% of pediatric deaths associated with COVID-19. Remarkably, PMIS has approximately a ten-fold mortality rate regardingthe rest of pediatric COVID-19 cases. These data indicate that prognosis is worse when the cardiovascular system is impaired during SARS-CoV-2 infection in children.

Table 11 Potential cardiovascular side-effects of the different drugs used against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection

Table 12 Summary of the recommendations that should be kept in mind when treatment with prolonging-QT interval are going to be used during coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic

Those patients with underlying heart diseases seem to be a vulnerable population at high risk if they contract COVID-19. Both, the new-onset acute cardiac complications and worsening of the basal state in patients with a low basal cardiopulmonary reserve or high-risk pro-arrhythmic profile, can occur in these children. Of note, not all patients with pre-existing heart diseases have the same risk for complications, and therefore, the hospital admission and anti-COVID drugs administration must be overweighed with the risk of nosocomial infections and side effects through a case by case approach. Furthermore, the delay of timely elective procedures and the radical decrease of in-person visits for the adequate follow-up at outpatient clinics may provoke those not-expected complications before the pandemic occur. To avoid preventable complications due to canceled visits and diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, pediatric cardiology specialists should review outpatient appointments and ensure that high-risk patients are prioritized.

Remarkably, a not negligible number of previously healthy infected children have experienced severe cardiovascular acute events in the form of the new PMIS,arrhythmia, pulmonary hypertension, heart failure, and even fulminant myocarditis.The commonest complication in this population was PMIS, which affects mostly previously healthy school-aged children and adolescents presenting with Kawasaki disease-like features and multiple organ failure with a focus on the heart. They frequently presented cardiogenic shock (53%), ECG alterations (27%), myocardial dysfunction (52%), and coronary artery dilation (15%). Most cases required PICU admission (75%) and inotropic support (57%), with the rare need for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (4%). Almost all of these children wholly recovered in a few days, although rare deaths have been reported (2%). These observations point out that,although infrequent, no child is free of the occurrence of cardiovascular events during the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

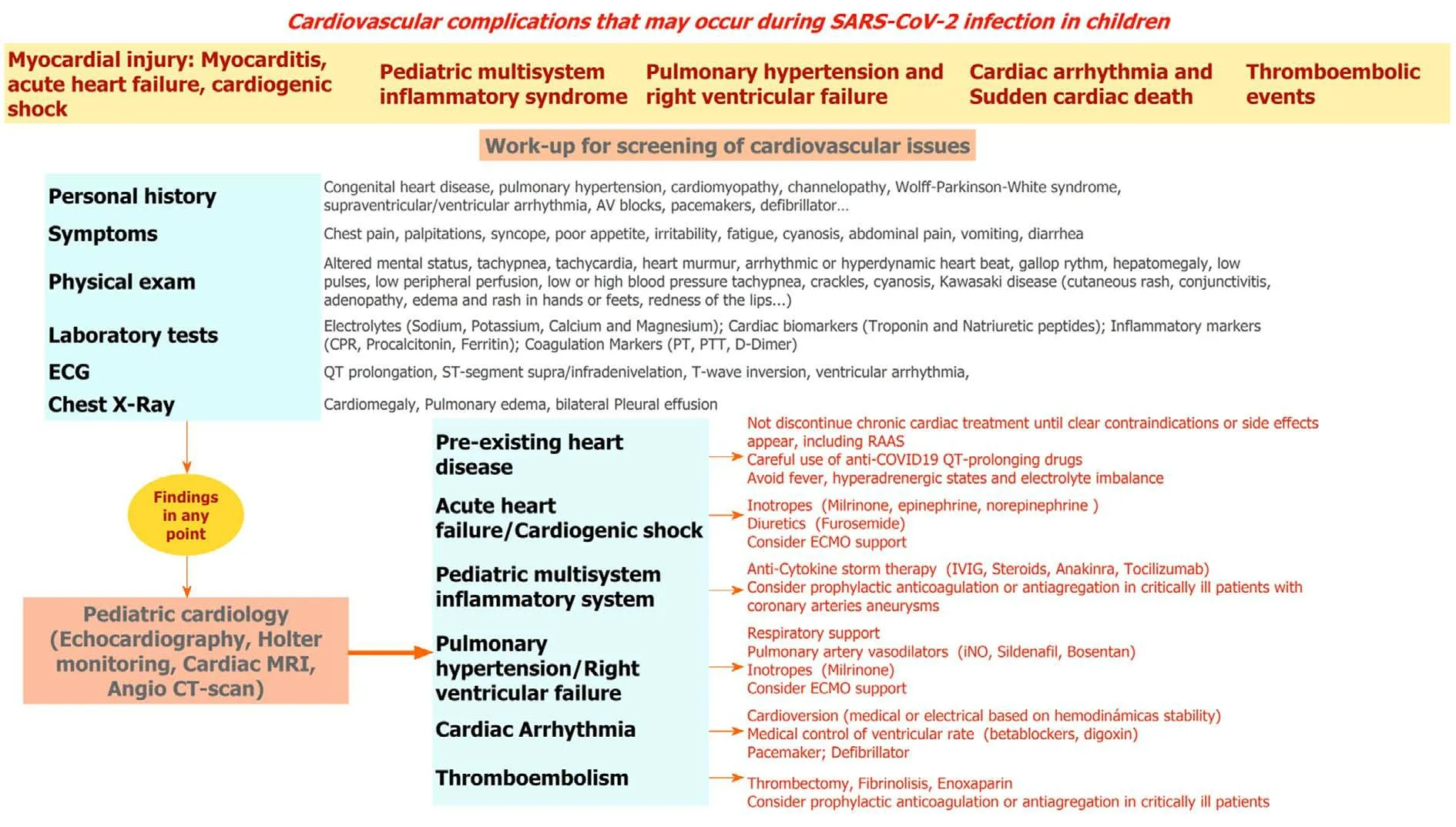

Failure to accurately identify and timely manage cardiovascular complications could lead to increased morbidity and mortality of these patients. Therefore, we recommend that those pediatric COVID-19 cases who are ill enough to require hospitalization should undergo a workup to the screening of cardiovascular issues(Figure 2). Also, close cardiovascular monitoring during hospitalization to avoid misdiagnosing these life-threatening entities should be warranted. The pediatric cardiology team should be involved in the management of any children with a preexisting cardiac condition and any previously healthy children with abnormalities on the screening workup. In absence of enough evidence, the management of cardiac complications once they are identified should be based on the current guidelines, local protocols and the physician´s experience for each individual condition[194].

CONCLUSION

There is still scarce data about the role of cardiovascular involvement in COVID-19 in children. Based on our review, the cardiovascular involvement seems to be a relevant factor of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Patients with pre-existing heart diseases constitute a high-risk population for development of a severe acute COVID-19 and for decompensation of cardiac conditions. In previously healthy children, PMIS has emerged as a novel and severe condition during the pandemic. Furthermore, COVID-19 can also produce fulminant myocarditis, ventricular arrhythmias and pulmonary hypertension in previously healthy children. Data suggest that prognosis is worse when the cardiovascular system is impaired during pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection,and that the vast majority of cardiac complications present a full recovery with a timely support. As the early identification and treatment of this entities is crucial, the performance of a cardiac workup and close cardiovascular monitoring of children with severe SARS-CoV-2 infection is highly recommended.

Figure 2 Summary of the potential cardiac complications and recommended cardiac work-up and management of cardiac complications for patients that require hospitalization due to severe coronavirus disease-2019 or for patients with pre-existing heart diseases.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Since the beginning of the pandemic, coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) in children has shown milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Cardiovascular involvement is emerging as one of the most significant and life-threatening complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)infection in adults.

Research motivation

To investigate if cardiovascular involvement could be a significant risk factor for severe COVID-19 in children.

Research objectives

We aimed to summarize the current knowledge about the potential cardiovascular involvement in pediatric COVID-19, in order to give a perspective on how to take care of them during the current pandemic emergency.

Research methods

A literature search to identify publications from January 1st, 2020 until July 31st, 2020.was conducted using PubMed and MEDLINE. Also, the websites of the health organizations including World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the website of the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center were reviewed to provide up to date numbers and infection control recommendations.The included studies were categorized by whether the study involved previously healthy patients or patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions. For pediatric multisystemic inflammatory syndrome (PMIS) temporally associated with COVID-19,multiple meta-analyses were conducted to summarize the pooled mean proportion of different cardiovascular variables in this population in pseudo-cohorts of observed patients. All the statistical analyses were performed using the STATA 14.0 (StataCorp.College Station, TX, United States).

Research results

We included a total of 193 articles in this review. The most relevant articles were 16 studies with size > 10 patients and with complete data about cardiovascular involvement in children with PMIS, 10 articles reporting sporadic cases of myocarditis,pulmonary hypertension and cardiac arrythmias in previously healthy children, and another 10 studies reporting patients with pre-existing heart diseases. The metaanalysis of 16 studies with size > 10 patients and with complete data about cardiovascular involvement in children with PMIS showed that PMIS affects mostly previously healthy school-aged children and adolescents presenting with Kawasaki disease-like features and multiple organ failure with a focus on the heart, accounting for most cases of pediatric COVID-19 mortality. Out of PMIS cases we identified 10 articles reporting sporadic cases of myocarditis, pulmonary hypertension and cardiac arrythmias in previously healthy children. We also found another 10 studies reporting patients with pre-existing heart diseases. Most cases consisted in children with severe COVID-19 infection with full recovery after intensive care support, but cases of death were also identified. There is an increasing concern about the delay of the diagnosis and adequate management of congenital heart diseases (CHD) complications and a delay of the optimal timings for corrections of some stable CHD due to the pandemic,with a potential direct effect on morbidity and mortality.

Research conclusions

There is still scarce data about the role of cardiovascular involvement in COVID-19 in children. Based on our review, all children (previously healthy or with pre-existing heart disease) with acute COVID-19 requiring hospital admission should undergo a cardiac workup and close cardiovascular monitoring to identify and treat timely lifethreatening cardiac complications. The management of the different cardiac conditions should be based on the correspondent clinical guidelines, expert panel recommendations and physician´s experience.

Research perspectives

Although cardiovascular involvement seems to be a crucial risk factor associated with severe pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection, more evidence in the form of multicenter collaborative studies is necessary to elucidate this association.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年21期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年21期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Strategies and challenges in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulcers

- Peripheral nerve tumors of the hand: Clinical features, diagnosis,and treatment

- Treatment strategies for gastric cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Oncological impact of different distal ureter managements during radical nephroureterectomy for primary upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma

- Clinical characteristics and survival of patients with normal-sized ovarian carcinoma syndrome: Retrospective analysis of a single institution 10-year experiment

- Assessment of load-sharing thoracolumbar injury: A modified scoring system