布加勒斯特建筑127年

——主导城市建设及在伊恩·明库建筑与城市规划大学任教的风云人物

埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库,安娜玛丽亚·安德里佐尤/Emil Barbu Popescu, Anamria Andritoiu

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

作者单位:埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库,伊恩·明库建筑与城市规划大学名誉校长/Emil Barbu Popescu, Honorary President, Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism

安娜玛丽亚·安德里佐尤,斯蒂芬·菲里米塔,菲里米塔建筑工作室创始合伙人/Anamria Andritoiu,Stefan Firimita, Founding Partners, Atelier Architecture Firimita

关于埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库

埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库生于1938 年9 月15 日。他先后担任布加勒斯特伊恩·明库建筑与城市规划大学(UAUIM)系主任(1996)、副院长(1998)、院长(2000)和校长(2008-2012),如今他依然是该校名誉校长。

他漫长的职业生涯始于1970 年从建筑学院毕业之时,此后他在学术界历经浮沉,达到最高的职业地位。他始终如一地探寻设计课程教学过程的现代化;他在担任系主任期间,制定了新的教学计划,包括转向学分系统;他建立了研究生课程,领导重组了研究生教学体系,并组织了继续教育执行委员会。

他的建筑实践生涯共完成80 余项建成项目,其中一些重要作品获得了国家和国际建筑奖项。他荣誉等身,包括2013 年获得“罗马尼亚建筑学会建筑奖”。

作为一个整体,埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库教授的教学和实践活动无疑是对建筑与城市发展的杰出贡献,同时也是罗马尼亚建筑教育事业发展的核心人物之一。

“我记得勒·柯布西耶去世前的一次访谈,他说,在我所处的年代,道德品行可以总结为:此生你必须有所作为。我的一生都执着追寻这一目标,在我所过之处留下痕迹!我还要补充的是,你应以谦逊、清晰、精准的姿态来完成这些事……艺术创作最适合的状态就是不骄不躁、持之以恒、坚持不懈、‘公正不阿’。这是勇气、尊重、内在强韧的展现,因为最终,只会剩下一个评判标准——那就是每个人的良知。”[1](斯蒂芬·菲里米塔 文)

本文试图从较为整体扼要的视野,呈现布加勒斯特建筑大学过去127 年的崛起,及其与罗马尼亚、尤其是布加勒斯特城市化进程之间有趣而密切的关联。从19 世纪末至整个20 世纪,罗马尼亚经历了诸多重要的历史事件及剧烈变迁,它们都给布加勒斯特留下了显著而不可逆转的痕迹与转变。然而,布加勒斯特建筑大学在过去100 多年中,通过那些在此学习并最终留校教学的建筑师的努力,为城市建设提供了一定程度的延续性和相对的稳定性——在此期间布加勒斯特经历了两次世界大战、5 种政治体制,还有一场摧毁了大部分城市的大地震。

1864 年,布加勒斯特正式出现了建筑高等教育的雏形,是作为路桥、矿业和建筑学院的一部分。然而,由于缺少学生以及对于机构化建筑教育的理解,这所学院未能持久,但它还是催生了建筑教育理念的萌芽。早期罗马尼亚建筑师大多在巴黎美术学院接受的教育,这批建筑师的辛勤工作真正奠定了布加勒斯特建筑教育的基础。1892 年,罗马尼亚建筑师协会创立了一所私立建筑学院。此前的1891年,该协会还创办了一本名为《建筑》的杂志(至今仍在刊)[2-3],这本杂志作为一个平台,用以阐释协会的理念,面向公众普及建筑职业及建筑教育的知识——这些专业知识在当时尚且鲜为人知,饱受误解。1897 年的教育改革将这所私立学校改制为国家建筑学院(由政府资助),并入国家美术学院。尽管几经更名和改革,这一教育形式仍不曾间断地持续至今[4]。

1 基塞莱夫路边酒馆,伊恩·明库/The Kiseleff Roadside Tavern,Ion Mincu (图片来源/Sources: SOCOLESCU T T. Monograph Ion Mincu [manuscript]. 1958.)

2 基塞莱夫路边酒馆,伊恩·明库,1892/The Kiseleff Roadside Tavern, Ion Mincu, 1892(图片来源/Sources: http://www.casadoina.ro)

3.4 女子学校,伊恩·明库/School for Girls, Ion Mincu(3.4图片来源/Sources: SOCOLESCU T T. Monograph Ion Mincu [manuscript]. 1958.)

About Emil Barbu Popescu

Emil Barbu Popescu was born on 15.09.1938.He has successively served as dean (1996), vicerector (1998), rector (2000) and president (2008-2012) of Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism (UAUIM) in Bucharest, where he currently holds the position of honorary president.

His long academic career started the moment he graduated the Institute of Architecture in 1970 and evolved through all the levels of academia until the highest distinctions. He permanently pursued the modernisation of the process of educating within the design studio; he formulated, while dean, the new educational plan, with the transition to the credit system. He organised postgraduate courses, led the reorganisation of the postgraduate education system and coordinated the Commission for the Implementation of the Continuing Education Programme.

His professional activities in the field of architecture have resulted in the completion of more than 80 built projects, the most important being the subject of national or international architectural awards. He has been the recipient of several distinctions and awards, including "The Prize for Architecture of The Romanian Academy"in 2013.

Considered as a whole, the activity on the didactic and professional level of prof. Dr. Arch. Emil Barbu Popescu can be appreciated as an exceptional contribution to the development of the activity of architecture and urbanism, as well as being one of the key figures in the continuing evolution of Romanian architecture education.

"I remember an interview of Le Corbusier shortly before his disappearance. He said: At my age, morality can be summarised in this way - in life you have to do something. I have been obsessively driven, all my life, to following this precept - to leave traces where I pass! I would add that you must do something with modesty, accuracy, precision...The only atmosphere suitable for artistic creation consists of modesty, continuity, perseverance, 'with just measure'. It is a demonstration of courage,of respect, of inner strength, because, ultimately,there is only one judgment, that of one's own conscience."[1](Text by Stefan Firimita)

The focus of this article is to present the interesting and tightly knit connection between the emergence of the University of Architecture in Bucharest, over 127 years ago and the history and urbanisation of the Bucharest in particular and Romania in a more generalised and schematic view.The end of the 19th century and the entire 20th century had seen many major historical events and drastic changes in Romania, all of which left their imprints and changed Bucharest in remarkable,irrevocable and very distinct ways. Yet, for more than 100 years during this period, the University of Architecture, through the architects that studied and eventually taught there, provided a sense of continuity and relative stability through two world wars, five political systems and a major earthquake that leveled out a great portion of the city.

In 1864, the first form of architectural higher education was legally established in Bucharest, as a part of the School of Bridges and Roads, Mines and Architecture. Although, for lack of students and understanding of what institutionalised architecture teaching meant, this school did not last long, it set the idea of centralised architecture teaching in motion.The first Romanian architects studied mostly in Paris,at the École des Beaux-Arts, and their enthusiastic undertakings lead to the true foundation of a school of architecture in Bucharest. Thus, in 1892 the Romanian Society of Architects set up a private school of architecture under its authority. The previous year,in 1891, the same Society established a magazine,Arhitectura (is still in publication today)[2-3], as a platform to clarify their mission and enlighten the general public on the subjects of the architectural profession and architecture education, subjects that was vastly unknown and misunderstood at the time. The Education Reform in 1897 transformed the private school into the National School of Architecture (financed by the government) as a part of the School of Fine Arts. Under various names and withstanding numerous reforms, this form of architectural teaching has endured without interruption to the present day[4].

Of that first generation of Romanian architects that founded the school of architecture and taught there, Ion Mincu (1851-1912) is one of the most illustrious examples. Although classically trained in the academic style in Paris, he was one of the first to understand the changes that modernity was bringing within architecture across Europe and bring it to his home country. In the new Romanian State,modernity manifested itself for the first time in the form of the neo-Romanian style, which represents the local variant of Art Nouveau, spread throughout Europe under different names, according to the traditions of each state. The Neo-Romanian style was born from the desire of Romanian architects to promote a movement that could be called "national",inspired mainly by the values and traditions of the old Romanian feudal and popular architecture,especially the church and the vernacular. In this sense, the architect understood that the only way to develop Romanian architecture was to implement the forms of popular architectural creation that had,over time, proved their validity, continuity and their adequate adaptation to the social needs of the new state. However, the Neo-Romanian style was not in tune with the fashion of the time, it was something entirely exotic and, as with all innovations, the first tendency was to reject it, to look at it with circumspection[3]. This perspective explains the small number of public buildings built prior to the First World War (in the early 1900s) in the new style. As such, Ion Mincu has a significantly small number of large scale or public projects, most of his projects consisting of houses.

伊恩·明库(1851-1912)是创立建筑学院的第一批罗马尼亚建筑师中最具代表性的一位。尽管他在巴黎接受了学院派的古典教育,但他却较早认识到,现代主义正给全欧洲的建筑领域带来变革,他也将这种变革带回了祖国。在新成立的罗马尼亚王国,现代主义最初体现为一种新罗马尼亚式风格,这可视为一种新艺术风格的地方变体——这一风潮已席卷欧洲,并根据各地传统被赋予不同名称。新罗马尼亚风格源自罗马尼亚建筑师对“民族主义”运动的推崇,这一运动主要来自旧罗马尼亚封建及世俗建筑的价值和传统,尤其是教堂及民居。在此意义上,建筑师认为发展罗马尼亚建筑的唯一方法,就是运用那些经历住时间考验的民间建筑形式,它们在时间长河中不断延续,并应用到新国家的社会需求之中。然而,新罗马尼亚风格并不符合那个时代的潮流,它具有一种彻头彻尾的异域风情,尽管有创新意义,但大部分人依然抱以谨慎态度,最初的反应就是拒绝这一风格[3]。在这一态度影响下,罗马尼亚在第一次世界大战之前(1900 年代)建造的新风格的公共建筑数量很少。伊恩·明库的大型公建项目也极少,大部分项目都是住宅。

一战后,也就是1930 年代,新兴现代主义运动的思想和美学体系就像它在所有其他欧洲国家的传播和实践一样,渗透至罗马尼亚社会之中。由于这一时机正好与布加勒斯特的高速现代化进程重合,新建筑风格被广泛应用于城市最具代表性的中心地带,为其赋予了一副现代主义的整体面貌,这在其他欧洲国家首都鲜有看到——那些首都城市大多在19 世纪便完成了现代建设。其中一个最显而易见的案例,就是新南北轴线的建设以及城市中心区的重建,也就是当时的塔切·伊恩内斯库-伊恩·C·布拉蒂亚努大道(如今的马格鲁大道)——这是当时布加勒斯特最重要的大型建设项目之一。尽管该项目始建于19 世纪末,并忠实采取了奥斯曼巴黎改造的模型,但大道两侧的建筑几乎都是一战后才建成的,并由现代主义风格主导。部分主要建筑是在1930 年代设计的,今天看到的主轴线风貌直到1950 年代末期才完成。这对该时期在布加勒斯特求学及工作的建筑师而言是一个极好的佐证,即如此大规模的城市项目竟可以在长达30 年的时间段、中间还被世界大战打断的情况下,保持如此独一无二的现代风貌——它的统一性仅在1977 的大地震中不幸遭到些许破坏。

有两位建筑师对这一现代建筑景观做出了重要贡献,他们也是当时罗马尼亚现代主义运动的核心人物——马塞尔·伊恩库(1895-1984)和霍里亚·克里昂加(1892-1943)。

5-8 塔切·伊恩内斯库-伊恩·C·布拉蒂亚努大道(现马格鲁大道)建筑/Architecture of the Tache Ionescu - Ion C.Bratianu Boulevard (today Magheru Boulevard)(5-8图片来源/Sources: MACHEDON L, SCOFFHAM E.Romanian Modernism: The Architecture of Bucharest 1920-1940. Cambridge, Massachusetts: M.I.T. Press, 1999.)

9 布塞吉疗养院,马塞尔·伊恩库/The Bucegi Sanitarium,Marcel Iancu(图片来源/Sources: BOCANET A, LASCU N,ZAHARIADE A M. Marcel Janco in Interwar Romania:architect, fine artist, theorist. [Marcel Janco centenary 1895-1995: catalogue]. Bucuresti: Simetria, 1996.)

马塞尔·伊恩库是前卫达达主义艺术运动的创始成员之一,与伊恩·维尼亚一起创建了罗马尼亚第一本前卫艺术杂志Contimporanul(1922),宣扬构成主义、未来主义和立体主义思想。伊恩库扮演着桥梁的角色,连接着西方世界的新兴进步思想与一战后重建的罗马尼亚刚涌现的现代主义运动[3]。两次大战期间的多座布加勒斯特住宅都出自他的设计。在罗马尼亚,与欧洲其他地方一样,私人住宅提供了新风格试验的最佳舞台,也是将新思想推向大众的完美媒介。因此,当时的富人及知识分子阶层风行建造现代主义风格的别墅或小型公寓楼,以彰显两次大战之间的罗马尼亚社会的经济实力[3]。

After the end of the First World War, the third decade of the twentieth century saw the penetration of the ideas and the aesthetic programme of the new Modern Movement, concurrent with their dissemination and implementation in all European countries. As this moment overlaps over the intense modernisation works of Bucharest, the new architecture is widely used in the central areas, representative of the city, which gives it a modernist general image, an aspect rarely found in other European capitals. that had seen their peak in development in the 19th century. An extremely clear and straightforward example is the development of the new North-South axis and restructuration of the central part of the city, the then Tache Ionescu - Ion C. Bratianu Boulevard (today Magheru Boulevard),one of the most important and major interventions in Bucharest of the time. Although begun at the end on the 19th century, in the true Hausmannian model, almost all the buildings flanking this artery are erected after the First World War and are dominated by the modern style. With some of its major buildings designed in the 1930s, the current form of the axis was finalised in the late 1950s. It is a testament to the architects that were educated and worked in Bucharest during this period that such a large scale urban intervention was given such a uniquely modern image over the span of 30 years and through the disruptions of World War II, the unity of which was somewhat unfortunately destroyed by the 1977 earthquake.

As a founding member of the avant-garde artistic movement DADA and founder (alongside Ion Vinea) of the first avant-garde artistic magazine Contimporanul (1922), advocating a mix of Constructivism, Futurism and Cubism, Marcel Iancu served as a bridge between the new, radically different ideas of the western world and the emerging modern movement of the newly formed,post First World War Romanian state[3]. A number of interwar Bucharest houses bare his signature.Individual houses in particular provided the perfect platform for experimenting with the new style, in Romania as well as in the rest of Europe, serving as the perfect medium for introducing new ideas to the wider public. It thus became a fashion for the wealthier and the more intellectually savvy to have villas or smaller apartment buildings designed in the new modern style, as a demonstration of the economic capacity of Romanian society in the interwar period[3].

With an architectural portfolio of works on a much larger scale, and considered as the"true founder" of Modernism in Romania, Horia Creanga's career is marked by a strongly personal interpretation of the international modern style,filtered through his own views and sensibilities.Unlike the European modernists, who deny all styles that went before them, Creanga is characterised by a more balanced vision that tends to incorporate or adapt local traditions and old Romanian folk art, a characteristic artistic choice that mark almost all Romanian architects. One of his most important and defining projects, ARO Building, with which he made name for himself in 1929, erected in 1931 and commissioned by the major insurance company by Asigurarea Romaneasca (ARO - Romanian Insurance Company) was an absolute novelty in Bucharest's architectural landscape at the time, both regarding its new geometrical and clean aesthetics,as well as due to its undeniably functional virtues[3].His large number of projects, most of which are in the urban environment, approached a wide variety of architectural programmes and, although most of these programmes were already well established, the functional solutions proposed by Creanga highlight numerous innovations and a dynamic and adaptable architecture. In 1935 Horia Creanga started the design of large industrial buildings (Malaxa Plants)and for the first time industrial architecture in Romania found its functional aesthetic expression.The development of technology and economic drive of the time provided an exceptional opportunity for the architects to reevaluate the efficient use of production spaces and deliver modern and aesthetic buildings by taking advantage of the possibilities offer by the use of reinforced concrete.

Characterised by horizontality and simplicity,the iconic image of Creanga's architecture sets a trend and establishes a theoretical and practical basis for evolution and assimilation of international and traditional architectural forms for other architects following in his footsteps, such as Duiliu Marcu and Octav Doicescu. These are the characteristics that mark the architectural development of inter-war Bucharest: a syncretic adaptation of modernism,Art-deco, vernacular and traditional elements grafted onto an urban fabric development policies reminiscent of Hausmann's Parisian grids for the core of the city and the European garden cities for new developments and the residential peripheries[3].

Some architects, such as Duliu Marcu, have careers that span over 50 years, both in the professional circle, as well as in academia. Duiliu Marcu's name is interlinked with the history of architecture in Romania during the first half of the 20th century, both literally, through his enormous professional contribution, as well as symbolically since he held the chair of the History of Architecture Department in the Bucharest Higher School of Architecture (the name of the University at the time) between 1929 and 1957.

10 ARO大楼,霍里亚·克里昂加/ARO building, Horia Creanga(图片来源/Sources: CIMPOERU V. Bucarest: les annees '30. Bucuresti: Noi Media Print, 1995.)

11 MALAXA植物园,霍里亚·克里昂加/MALAXA Plants, Horia Creanga(图片来源/Sources: Collection of photographs,Department of History, Architectural Theory and Heritage preservation, University of Architecture and Urban Planning"Ion Mincu".)

12-14 罗马尼亚铁路公司CFR建筑群,杜柳尔· 马尔库/Administrative buildings of the Romanian Railroad Company (CFR), Duiliu Marcu(12-14图片来源/Sources: C.F.R. Administrative Palace Bucharest, 1939.)

霍里亚·克里昂加的设计作品规模较大,被认为是罗马尼亚现代主义“真正的创始人”。他的职业生涯是对国际现代风格强烈的个人化诠释,融入了他自己的所思所感。不同于那些试图否定推翻所有历史风格的欧洲现代主义者,他采取了一种更加均衡的视野,融入或适应于罗马尼亚的地方传统及民俗艺术——这种个性化的艺术道路,在几乎所有罗马尼亚建筑师身上都可以见到。他最著名、最具代表性的项目之一ARO 大楼设计于1929 年、建成于1931 年,让他一举成名,由罗马尼亚保险公司委托,在当时布加勒斯特的建筑景观中绝对堪称一项创举——不仅就其新潮的几何构图和简洁的美学价值而言,而且还归功于其不容置疑的功能优势[3]。他主持的项目为数众多,且大多位于城市,涉及的建筑类型十分多样。尽管大部分建筑类型早已成熟,但克里昂加提出的功能方案还是会带来诸多创新点,形成一种高度灵活、适用的建筑。1935 年,霍里亚·克里昂加开始设计大型工业建筑(马拉萨电厂),推动了罗马尼亚工业建筑第一次获得功能上的美学表达。新技术的发展以及那个时代的强劲经济动能为建筑师提供了绝无仅有的机会,以重新考量生产空间的高效使用,并利用钢筋混凝土的技术优势探索建筑的现代美学表达。

克里昂加的建筑以水平延展和简洁形象著称,他的作品为杜柳尔· 马尔库、奥卡夫特·多伊切斯库等后代建筑师确立了发展方向,并为国际式及传统建筑形式的演化和同化建立了理论和实践基础。这是两次大战之间布加勒斯特建筑进程的重要特征:将现代主义风格、装饰艺术风格、乡土和传统元素进行整合和调整,嵌入这样一个城市肌理之中,这种肌理令人想起奥斯曼改造的巴黎中心区格网,以及欧洲在新城建设及住宅区中采取的花园城市理念[3]。

如杜柳尔· 马尔库等,建筑师的职业生涯可长达50 余年,横跨职业圈和学术圈。杜柳尔· 马尔库的大名与20 世纪上半叶的罗马尼亚建筑史密切交织:在物质层面,是因其卓越的建筑实践贡献;而在名誉层面,他于1929-1957 年长期担任布加勒斯特高等建筑学院(当时的建筑大学)建筑史系主任的职务。

(1)硕士及以上学历,主治医师及以上职称;(2)熟练掌握一门外语,达到熟练阅读、翻译和基本会话能力,尤其是英语;(3)在三级医院骨科工作5年及以上;(4)有国外留学经历者优先。

在罗马尼亚的城市景观中,尽管民族建筑教育的兴起以及年轻罗马尼亚建筑师竞逐现代建筑浪潮的整体热情,为一战前及两次大战之间的建筑创新提供了十分丰沃的土壤,但二战后的布加勒斯特则呈现出完全不同的景象。从二战结束至1950 年代末,城市的主要特征是寻求平衡并修复战争造成的破坏,转译到建筑生产上便表现为一种对前人发展的自然沿袭。战前开始实践的建筑师基本上延续了自己的设计风格,因而一些因战争而终止的投资项目也得以继续。1945 年后,建成了一系列重要的公共项目,采取从现代主义到新古典主义等各不相同的风格样式,并发展出一种显著的古典派现代主义风格:如班洛克总部大厦和赫拉斯特劳海军俱乐部(建筑师奥卡夫特·多伊切斯库)、财政部大厦(建筑师拉杜·杜德斯库)、CFR 建筑群 (建筑师杜柳尔· 马尔库)[3]。

这个时期更重要的或许是新功能主义理念的建筑实验,尤其显著地体现在米尔切亚·阿利法蒂等建筑师的作品中。他在杜柳尔· 马尔库事务所开始自己的职业生涯,在很长一段时间的建筑和建造实践中经历了复杂、多面的演变,他还同时兼任布加勒斯特建筑大学和土木工程大学的教授。他设计的项目包括伯尼亚萨国际机场(1946,建筑师米尔切亚·阿利法蒂、阿斯卡里奥·达米安等)、APACA服装厂(1947,建筑师米尔切亚·阿利法蒂等),实验性地彰显出多种表现性的方向及语汇,体现出比两次大战期间更雄厚的胆识,并带有一种这个时代似乎非常赏识的现代主义者的自由表达[3]。

然而,这一时期活跃的建筑师的风格延续性、实验性及创造力皆受到同期罗马尼亚所经历的社会及政治变迁的牵制。苏联广泛流行的新社会主义风潮对布加勒斯特城市肌理的影响极小。住宅开发依然延续了实验性的现代主义风格或花园城市规划,而非苏联常见的方格形社区。

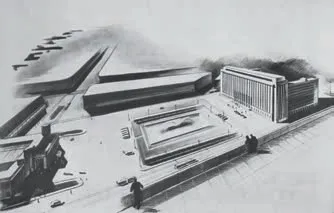

这一短暂时期完成的真正社会主义风格的重要项目很少,值得一提的是罗马尼亚新闻出版大楼,由米尔切亚·阿利法蒂设计、建设于1950-1955 年。20 世纪这段时期最显著的影响,就是回归19 世纪流行的古典主义风格,还见证了过去几十年盛行的现代主义风格的回潮。提到这段插曲中的建成作品,值得一提的是1953 年由奥卡夫特·多伊切斯库设计的罗马尼亚国家歌剧院;而放在更广阔的图景中,建筑景观对民族身份的持续追逐确保了现代主义永远不会完全退出罗马尼亚的历史舞台。黑海沿岸的建筑是1950-1960 年代的典型风貌,此外还可见于布加勒斯特的基瑟勒夫大街两侧的一大批私人住宅,以及为上流阶层建造的新住宅区。

While the emergence of national architectural education and the general enthusiasm of young Romanian architects to compete and learn from modern trends had provided a fertile environment for creativity in the pre and inter war Romanian urban landscape, a very different scene is set for Bucharest after the Second World War. The period up to the end of the 1950s is marked by the search for balance and the need for restoration after the destruction of the war, translated in the architectural production by a feeling of a natural continuity with the previous evolution. Architects who had practiced before the war generally continue their own design style, to the extent that some of the investments already started are resumed. After 1945, a series of important public constructions are completed, in different stylistic manners, from modernism to neoclassical, passing through an emphatic classicist modernism: the Banloc office block and the Herastrau nautical club (arch. Octav Doicescu), the Ministry of Finance (arch. Radu Dudescu), CFR palace (arch. Duiliu Marcu)[3].

Perhaps more significant for this period is search for and the experimentation with the new functionalist ideas, especially visible in the works of architects such as Mircea Alifanti. He was an architect that had started his career with Duiliu Marcu and had complex and multifaceted evolution spanning a long period of time, both in the architecture and construction fields, as well as a professor at both the University of Architecture and the Construction University in Bucharest. Projects such as Baneasa International Airport (1946, arch.M. Alifanti, A. Damian, & all) APACA clothing factory (1947, arch. M. Alifanti, I. Ghica-Budesti,V. Krohmalnic, H. Stern, & all) are indicative of the experimentation with various expressive orientations and vocabularies, manipulated with greater audacity than in the interwar period, within a modernist freedom of expression to which the era seemed to be favourable[3].

Yet, the stylistic continuity and the experimentation and personal creativity of the architects active during this period is tempered by the social and political changes that were happening in Romania at the time. Some of the new socialist trends that were widely spread in U.S.S.R. had minimal impact on the urban fabrics of Bucharest.Housing developments continued the previous trend of experimental modernist arrangements or garden city planning, as opposed to the soviet square block.

Few important projects were completed during this short period in the true socialist realist style,the most relevant one being Complexul Tipografic Casa Scanteii (Romanian Newspaper and Printing House), built between 1950-1955 by Mireca Alifanti. The most notable influence of this period of the 20th century is the return to the classical style popular in the 19th century and a veering offthe modernist influences that had been flourishing in the last decades. This very short interlude is seen in buildings such as the Romanian National Opera House by Octav Doicescu in 1953 while, in the greater scheme of things, a continuing search for national identity in the architectural landscape ensures that a clean break with modernism never happens. The architecture on the Black Sea coast is relevant as an image for the 1950s through the 1960s as well as a lot of private villas built in Bucharest along Kiseleff Boulevard and in new residential developments for the more influential members of society.

This is especially relevant since, in the late 1960s a resynchronisation with European ideas is apparent within the architectural language in Bucharest.

The architects that teach and build in Romania at the time never gave up on the modernist dream despite the changing political climate and the increasing centralisation of the profession. The architecture school, through an entire generation of former students that were now leading exponents of the younger generation of modern professionals,also played an important role. It managed to change its orientation despite the political rigors of the time and, through persons such as Ascario Damian,rector of several legislations, Mircea Alifanti, Octav Doicescu, Horia Maicu, Grigore Ionescu and others that taught at the University in Bucharest though the 1960s and 1970s, education begins to assimilate the most open contemporary trends.

15.16 巴内萨机场,米尔切亚·阿利法蒂/Baneasa Airport,Mircea Alifanti

17-19 罗马尼亚国家歌剧院,奥卡夫特·多伊切斯库/Romanian National Opera House, Ocatv Doicescu(15-19图片来源/Sources: IONESCU G. Architecture in Romania during the years 1944-1969. Bucharest: Academiei Publishing House RSR, 1969.)

20-22 斯拉蒂纳青年科技文化之家,埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库,多林·斯蒂芬/The Culture House of Science and Technics for Youth, Slatina, 1971-1986, Emil Barbu Popescu, Dorin Stefan

23-25 布加勒斯特奥林匹克之家,埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库/The Olympic House, Bucharest, Emil Barbu Popescu(20-25供图/Courtesy of Emil Barbu Popescu)

这种现象到了1960 年代末更加凸显,布加勒斯特的建筑语汇开始与欧洲的思想重新同步。当时,尽管政治空气在变化,行业的集中化愈发凸显,但在罗马尼亚教学与实践的建筑师并未放弃对现代主义理想的追逐。建筑学院在其中亦发挥着重要作用,此前培养的一代建筑师如今正在年轻一代的现代主义实践中发挥了领导作用。在紧张的政治氛围下,这一批建筑师依然选择改弦易辙,尤其是在曾担任多所学院校长的阿斯卡里奥·达米安,以及米尔切亚·阿利法蒂、奥卡夫特·多伊切斯库等曾于1960-1970 年代在布加勒斯特大学执教的建筑师的努力下,罗马尼亚的建筑教育仍然紧跟最开放的当代建筑潮流。

从1970 年代初算起的20 年间,尤其是1977年的毁灭性大地震后,罗马尼亚和布加勒斯特的建筑风格逐步稳固下来,特定项目皆采取特定的风格类型,极少有建筑师个人的创造空间。一些年轻建筑师不甘随波逐流,在艰难的限制条件下创造出独特的作品,他们也是布加勒斯特伊恩·明库建筑学院的教学中坚力量。这些项目包括伦尼库·维尔切亚科技宫(1974-1982,建筑师埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库、斯蒂芬·隆古、皮特·坎内特)、斯拉蒂纳青年科学与技术文化之家(1971-1986,建筑师埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库、多林·斯蒂芬)、位于布加勒斯特的国家邮政总局(1986,建筑师佐尔坦·塔卡茨、V·西米翁、F·埃切里姆)。这些项目皆不同于该时期的大部分建筑,带给人难能可贵的趣味和愉悦,它们也彰显了这一代年轻建筑师在陈规之下工作的创造性和灵活性[3]。埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库的个性印记已镌刻在罗马尼亚和布加勒斯特的建筑景观之上,他也与伊恩·明库建筑与城市规划大学的发展密不可分,对这所大学取得今天的地位做出了不可磨灭的贡献。

1990 年以后,再次解放的建筑实践氛围带来多样化的风格和实验的自由。然而,这一过渡时期的大部分建筑师皆不熟悉独立实践,且与过去40 年罗马尼亚错失的建筑潮流及建筑思想格格不入。埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库、多林·斯蒂芬等少数建筑先驱再次站了出来,他们在这个混乱而迷失的时期设计了第一批具有连贯过渡意义的建筑。例如布加勒斯特足球宫(2001-2002,建筑师埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库)等项目,体现了国家层面上当代建筑思潮所应具备的品质和内涵,为其他罗马尼亚当代建筑师树立了标准。

过去20~30 年间,罗马尼亚、尤其是布加勒斯特的建筑学院愈发感受到肩上的重担,即如何培养出如此的新一代建筑师,不仅能够延续一个多世纪以来逐步确立的传统,而且能够适应当下这种混乱、乃至矛盾的职业环境。1990 年代末期,大部分较大城市皆爆发出新建设和规划策略的需求,也亟需与此相适应的法律法规。这些新规划往往是匆匆制定的,且缺乏对于真实城市现状和无法预知的发展速度的深入理解,亦不自知这些规划方案所依托的理念模型。诸多类似的境遇给21 世纪前10 年参与实践的建筑师带来极大的困难及挑战。在这种持续变化的不确定环境下,建筑教育亦不得不寻求更高的灵活性。罗马尼亚的建筑职业界与布加勒斯特建筑与城市规划大学之间的共生关系持续至今,有时候学校会直接参与到城市规划之中(如2000 年布加勒斯特城市总体规划),但更多是体现在学院的师生及其对当代罗马尼亚建筑风貌的影响之上。□

For two decades, starting with the early 1970s more noticeable and impactful after the devastating earthquake in 1977, architecture in Bucharest and in Romania becomes more stylistically fixed,with certain approved typologies for projects and little leeway for individual professional creativity. A few young architects stand out from the uniformity to perform exceptional works under difficult constrictions while also active within the architectural education at the Institute of Architecture Ion Mincu in Bucharest. Projects such as The House for science and technology from Râmnicu Vâlcea (1974-1982, arch. Emil Barbu Popescu, Stefan Lungu, Petre Ciuta), The Culture House of Science and Technics for Youth, Slatina(1971-1986, arch. Emil Barbu Popescu, Dorin Stefan) or Romanian Post Office in Bucharest (1986,arch. Zoltan Takacz, V. Simion and F. Echeriu) are interesting and happy exceptions from the norm during this period and a clear indicator of the creativity and flexibility of the young generation of architects capable of working within and around rather inflexible norms[3]. The personality of Emil Barbu Popescu has left its mark on the architectural landscape of Romania and Bucharest, while also being inexorably linked with the name and evolution of Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism for his extraordinary contributions to making the school what it is today.

After 1990, the once again liberalisation of the architectural practice ensured stylistic diversity and freedom of experimentation. Yet, most of the architects that were practicing during this transition period were unfamiliar with independent practice and also out of touch with architectural trends and some architectural programmes that had not been needed in the previous four decades. It is again architects such as Emil Barbu Popescu and Dorin Stefan and few others who design the first coherent transitional architecture in a period of confusion and relative lack of direction. Projects such as The House for Football, Bucharest (2001-2002, arch.Emil Barbu Popescu) set the bar for other Romanian contemporary architects as it pertains to the quality and understanding of how current architectural trends and programmes can be implemented in the national landscape.

During the last 20 to 30 years a huge burden has fallen on the schools of architecture in Romania and in Bucharest in particular, that of educating a new generation of architects to continue with the tradition set forth more than a century ago,and doing so in a professional climate governed by confusing and sometimes contradicting situations.In the late 1990s there was a great need for new development and urban planning strategies for most of the bigger cities and all the laws and regulations that come with these strategies. More often than not, these plans were hastily put together and lacked an in-depth understanding of, firstly the real urban situation and the unforeseen at the time speed of development and secondly of the models on which they were based or were adapting.This, and other similar situations, gave birth to the difficult and challenging context for architects intending to practice in the first decades of the 21st century. It was also one of the leading motivators for an undeniable flexibility in teaching architecture in an ever-changing and unsure environment. The symbiotic relationship between the professional part of the architectural practice and the academic standing of the University of Architecture and Urban Planning in Bucharest continues to this day, sometimes seen as direct involvement in urban planning (the General Urban Plan for Bucharest,2000) but more often through its students and professors and their impact on what the architecture in Romania looks like today.□

26.27 蒂米什瓦拉奥林匹克游泳馆,埃米尔·巴尔布·伯佩斯库/Olympic Swimming Pool, Timisoara, Emil Barbu Popescu(26.27摄影/Photos: Cosmin Dragomir, 供图/Courtesy of Emil Barbu Popescu)

参考文献/References

[1] POPESCU M. Dialogues with Emil Barbu Popescu.Publishing House of Literary Bets, Bucharest, 2016.

[2] Arhitectura. http://arhitectura-1906.ro/revistaarhitectura-110-ani/[2020-01-15].

[3] F u n d at i a C u l t u ra l a Me t a. ht t p://w w w.e-architecture.ro[2020-01-15].

[4] Universitatea de Arhitectura si Urbanism "Ion Mincu". https://www.uauim.ro/universitatea/istoric/[2020-01-15].