Place preference to a parent and neuroendocrine responses in preweanling mice

MA Xiao-mei, LIU Chao-bao, HE Chen, WANG Jian-li

(1. Key Laboratory of Ecology Model and Applications of State Ethnic Affairs Commission; 2. College of Biological Sciences and Engineering, North Minzu University, Yinchuan 750021, China)

Abstract The close parent-infant bonding before weaning is critical in mammals, which facilitates the emotional attachment between each other. However, the mechanisms on filial emotional attachment towards a parent remain poorly understood. Arginine vasopressin (AVP) and corticosterone (CORT) play important roles in social interaction and social bonding. This study aimed to investigate the potential mechanisms on parent-induced attachment in ICR mice pups through conditioned place preference (CPP) test. We investigated place preference of pre-weanling male pups following four days′ maternal or paternal reinforcing, while the immunoreactive (IR) neurons of hypothalamic AVP and c-Fos were detected by immunohistochemistry staining. In parallel, the levels of serum CORT were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in mice pups. The pups conditioned with a parent showed place preference for the chamber paired with dam or sire cue with a corresponding increase in c-Fos expression in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) and a decrease in serum CORT levels compare to the pups conditioned with empty chamber (P<0.05), and the pups conditioned with dams displayed higher levels of AVP expression in the PVN (P<0.05). In comparison with the pups conditioned with sires, the pups conditioned with dams showed lower levels of PVN c-Fos expression (P<0.05) and serum CORT concentration (P<0.05). There were not significant differences in c-Fos-and AVP-IR expression in the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus (SON)(P>0.05). These results indicate the pre-weanling pups display place preference when conditioning with mothers or fathers. The neuronal activation and AVP release in the PVN and alterations of serum CORT may contribute to a parent induced-preference, and there were some differences with respect to the neuroendocrine activities of pups between maternal and paternal conditioning.

Key words ICR mice; place preference; arginine vasopressin; corticosterone; c-Fos

In mammals, parents interact with their young in the most appropriate manner to fulfill the most important biological goal: ensuring the growth and survival of the offspring[1]. In addition, parental care is one of the most important factors shaping the brain and behavior of offspring[2]. Thus, parent-infant bonding is critical in mammals. There exists a positive-feedback between parents and infants, such that social and affiliative interactions within the parent-infant dyad facilitate bonding between them, resulting in more frequent parental behavior[3]. The demands of nursing ensure regular maternal contact with infants through weaning, and, in many mammalian species, infants and mothers maintain close physical proximity throughout the pre-weaning period[4]. Pups can be highly rewarding to the postpartum dam. This has been shown in the conditioned place preference (CPP) test, where early lactating mothers will actively work to gain access to her pups[5]. Similarly, monogamous mandarin vole (Microtusmandarinus) fathers can form pup-induced CPP throughout the entire postpartum period, indicating that pups are a strong reinforcing agent to their fathers[6-7]. Attachment is a reciprocal emotional bond between an infant and caregiver. Parallel to studies that investigate the emotional attachment of pups to both their mothers and fathers are relative rare. In two-choice tests, sheep and guinea pig pup preferences are used to indicate levels of emotional attachment following separation from mothers[8-9]. Similarly, mandarin vole pups spend more time approaching their mothers, and emitted more calls on their mother′s side compared to an unfamiliar female; they also show a preference for their fathers over an unfamiliar male[10-11]. Theses findings indicate that paternal stimuli could serve as a reinforcing agent to pups, and it has been demonstrated in preweanling mouse pups via the CPP test[12]. However, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying offspring attachment to parents remain poorly understood.

Central arginine vasopressin (AVP) and oxytocin (OT) modulate a range of species typical behaviors, including social recognition and memory, maternal-infant attachment, offensive aggression, defensive fear reactions, and reward seeking[13-14]. Recent studies have found that OT and dopamine activity contributes to the pup′s preference to the mother and father[12, 15]. Sex differences exist in the function of the OT and AVP systems. AVP is androgen dependent and is more abundant in the male brain than in the female brain, and it is necessary for social behaviors in male rats and mice[16]. AVP producing neurons are found in the densest clusters in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and the supraoptic nucleus (SON) of the hypothalamus. Hypothalamic AVP systems have different sensitivity in males versus females. For example, male prairie voles (Microtusochrogaster) are more sensitive to AVP than female voles in displaying partner preferences, indicating sex differences in the neuropeptide regulation of pair bonding[17]. However, there is no information available on AVP′s involvement in maintaining a filial bond. AVP is involved in emotional and social behavior via interaction with stress hormones in the hypothalamic pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis[18]. Corticosterone (CORT) is a regulator of certain parental behaviors and attachment[19], and increased plasma CORT promotes the formation of partner preferences in monogamous prairie voles[20]. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that AVP and CORT may mediate pup preference behavior.

Unlike other laboratory mice strain, male ICR mice display mate-dependent parental retrieval behavior only for their own biological pups. This unique ability of ICR sires contributes to the increased survival rate of the pups and to the high level of social attachment and interaction between sire and pup[21], making ICR mice an ideal system to study the reinforcing property of parents to pups[12]. c-Fos, a protein product of the immediate early genec-fos, was often used as a neuronal activation marker. Here, we examined the expression of hypothalamic c-Fos and AVP immunoreactive (IR) neurons and serum CORT levels in male ICR pups forming preference for dam and sire.

1 Materials and methods

1.1 Animals

ICR mice were purchased from Ningxia Medical University Laboratory Animal Center (Yinchuan, China). The animals were housed in groups of four in polycarbonate cages (32 cm×21.5 cm×17 cm, length×width×height) and had ad libitum access to food and water. The colony room was operated on a 12-h light/dark schedule (lights on at 08:00) and was maintained at an ambient temperature of 23 ℃± 2 ℃. The day pups were born was denoted as postnatal day (PND) zero (day of birth=PND 0). Pups were weaned at PND 21-23, and PND 17-21 male pups were used for the present study. All experiment procedures were performed strictly in accordance with the guidelines published in the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

1.2 CPP test

The place preference apparatus consisted of two large compartments (34 cm×25 cm×32 cm, length×width×height) with different visual cues (gray walls or white-black striped walls) separated by a small middle compartment (11 cm×25 cm×32 cm, length×width×height). The middle compartment served as the acclimation compartment, and had a door (7 cm×9 cm, height×width) in the center of the base.

Pre-test: on the day prior to conditioning, PND 17 pups (n=34) from different litters were tested to determine whether they had any innate individual preferences to either of the two lateral compartments. Each pup was given free access to the decorated compartments, and the time spent in the two lateral compartments was recorded for 15 min by a camera (Sony, HDR-XR260E) mounted 70 cm above the arena. The time spent in different compartments was scored by an experimentally blind rater. After each trial, the compartment was wiped using 70% ethanol. Pups showed no inherent preference for either compartment.

Conditioningwithmother: pups were conditioned in an alternate half-day design. In the morning, a pup (n=12, each from different litters) cohabited with her mother for 1 h in one of the outer compartments; in the afternoon, the pup was placed alone in the opposite compartment. We followed this counter balanced sequence for 4 days. The pup therefore underwent four consecutive days of conditioning, where it was alternately reinforced with the mother or empty chamber for 1 h in the morning or afternoon. On the fifth day, the pup was given a 15 min test (post-test) without the presence of the mother.

Conditioningwithfather: a different subset of pups (n=16, each from different litters), were alternately reinforced with their father or empty chamber. Conditioning sessions and post-test procedure were the same as the mother conditioning described above.

1.3 Immunohistochemistry

We compared the difference of c-Fos and AVP expression in pups with preferences for mother or father. The mice were assigned to one of three treatment groups: mother conditioning group (MC,n=6), father conditioning group (FC,n=6), and the control group (CK,n=6), which received no unconditioned stimulus-cue conditioning and were only exposed to cues that served as the conditioned stimuli for the experimental group. Animals were exposed to each cue-decorated compartment for 1 h in an alternating sequence, matching the parameters for the treatment of the experimental group.

After a 15 min post-test, animals were deeply anesthetized and perfused with 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.4) and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PBS. The brain was removed and placed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Prior to dissection, brains were immersed in 30% sucrose until saturated. Coronal sections (40 μm) were cut on a cryostat and consecutive sections collected in two vials containing 0.01 mol/L PBS for staining. Vials containing sections were incubated for 10 min with 3% H2O2, and then washed for 4×5 min with 0.01 mol/L PBS. Sections were preincubated for 90 min with normal goat serum (SP-0023) and incubated at 4 ℃ overnight in primary antibody solution containing 1∶100 c-Fos antibody (sc-52; Sant Cruz) or 1∶5000 AVP antibody (AB1565; Upstate, Lake Placid USA) diluted using antibody diluent (0.01 mol/L PBS containing 20% bovine serum albumin and 1.7% Trition-X-100). The next day, sections were washed 4×5 min with 0.01 mol/L PBS and incubated for 60 min in a water bath 37 ℃ with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (SP-0023), followed by another round of 4×5 min 0.01 mol/L PBS. After 60 min of incubation with S-A/HRP (Bioss Company, Beijing, China) and 4×10 min washing with 0.01 mol/L PBS, sections were stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride for visualization.

1.4 Measurement of immunoreactive neurons

Slides were inspected under a microscope to identify the forebrain regions for quantification. For each brain nucleus, three representative sections were chosen from anterior to posterior anatomically matched regions per sample, and neurons from these regions were used for data collection to minimize variability. Immunoreactivity is given as immunopositive cells per mm2under×100 magnification (Motic microscope). Individual means for each animal were obtained by counting positive neurons in the three sections from each nucleus. For all subjects, a trained experimental rater that was blind to the specific experimental treatments counted positive neurons. Sections were chosen by correspondence to the reference atlas plate, not by the level or intensity of Fos-IR and AVP-IR labeling. Sections were imaged with Motic microimaging systems (Motic China Group CO., LT, China).

1.5 Serum CORT assays

Blood samples were collected directly in Eppendorf tubes from the heart after euthanasia from the above experiment. After collection, samples were immediately centrifuged and separated, and serum was stored at -20 ℃. Serum CORT levels were determined by a mouse CORT ELISA kit following the manufacturer′s instructions (Kaierwen Biotechnology, Suzhou, China). The absorbance of the resulting ELISA mixtures was measured within 5 min at 450 nm using a using a Bio-Rad iMark.

1.6 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0. Data were checked for normality using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. CPP data were compared using paired-samplest-tests. Immunohistochemical data and serum CORT concentrations were analyzed using one-way ANOVA. Group differences were compared using a Bonferroni post-hoc test. All data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE) and alpha was set at 0.05.

2 Results

2.1 CPP test

Pre-test: pups exhibited approximately equal time in the two lateral compartments (gray chamber and striped chamber) (t33=-1.086,P=0.285) (Fig. 1a), suggesting that the apparatus is an unbiased environment.

Post-test: after 1 h of conditioning with dam or sire alone, pups developed a preference for the mother cues (t11=-2.714,P=0.02) or father cues associated chamber (t15=-2.526,P=0.023) (Fig. 1b-c).

(a) pre-test, (b) post-test following mother conditioning, and (c) post-test following father conditioning. * indicates significant differences (P<0.05)

Figure1Timespentbypupsinthedifferentapparatuscompartments

2.2 c-Fos and AVP expression

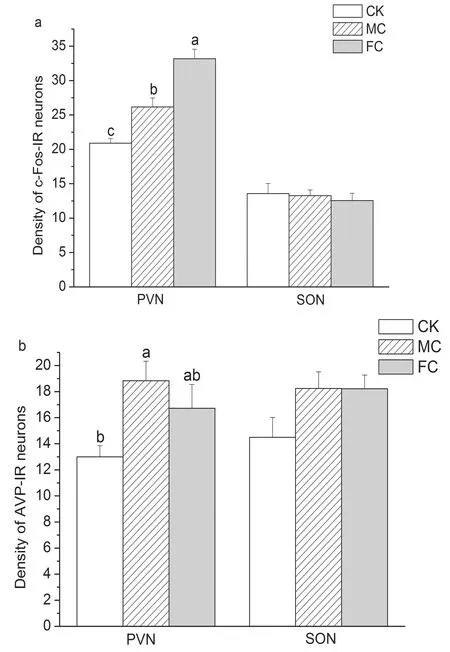

We observed significant effects of different conditioning regimes on AVP (F(3, 20)=4.136,P=0.037) and c-Fos (F(3, 20)=27.572,P<0.001) expression in the PVN. Compared to the CK group, the MC group displayed more AVP-IR neurons (meandiff=5.833,P=0.012) and c-Fos-IR neurons (meandiff=5.278,P=0.006) in the PVN. In comparison with the CK group, the FC group showed increased c-Fos-IR neurons in the PVN (meandiff=12.278,P<0.001), but we did not observe a significant difference in the PVN AVP expression (meandiff=3.722,P=0.090). There were no significant differences in AVP-IR neurons in the PVN between the MC and FC group (meandiff=2.112,P=0.320), but there was a significant difference in c-Fos-IR expression (meandiff=-7.000,P=0.001). We did not observe significant differences in AVP-IR (F(3, 20)=2.030,P=0.166) and c-Fos-IR expression (F(3, 20)=0.211,P=0.812) in the SON among three groups (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).

Groups that do not share the same letters are significantly different. PVN, paraventricular nucleus; SON, supraoptic nucleus; CK, control; MC, mother conditioning; FC, father conditioning

Figure2Thenumberofc-Fos-(a)andAVP-IR(b)neuronsin

thePVNandSONinpupswiththedifferentconditioningregimes

Bar=100 μm. PVN, paraventricular nucleus

Figure3Immunopositivestainingforc-Fos(a-c)andAVP(d-f)incontrol(aandd),motherconditioning(bande),andfatherconditioning(candf)regimes

2.3 The levels of serum CORT

The different conditioning regimes had significant effects on serum CORT levels (F(3, 20)=159.109,P<0.001). Compared to the CK group, the MC group (meandiff=-49.405,P<0.001) and FC group (meandiff=-8.768,P=0.01) showed lower levels of serum CORT. In addition, the MC group had a significantly lower level of serum CORT compared to the FC group (meandiff=-40.637,P<0.001) (Fig.4).

Groups that do not share the same letters are significantly different.CK, control; MC, mother conditioning; FC, father conditioning

Figure4ConcentrationsofserumCORTinpupswiththedifferentconditioningregimes

3 Discussion

In mandarin voles, pups prefer their mothers or fathers over strange females or males in two-choice test from PND14 to 21[10-11]. Similarly, preweaning ICR female pups prefer their mother or fathers in a CPP test[12]. Although the male ICR mice showed inferior learning and memory abilities than females[22], we found that male pups exhibit a preference to the chamber associated with father or mother cue. The increases in c-Fos-IR neurons are routinely interpreted as evidence of increased neuronal activity. Pups showed a high density of c-Fos-IR neurons in the PVN when preferring to their fathers or mothers. Furthermore,the place preferences of pups for mother and father led to different c-Fos expression in the PVN. The amount of maternal licking and grooming received by pups is more than that of paternal licking and grooming. The quantity differences of activated hypothalamic neurons may speak out for dissimilarities in response to father and mother.

We found that pups conditioned to dam showed higher AVP-IR neurons in the PVN. This might represent a mechanism by which increased AVP could be linked to the infant′s preference to a parent. The co-localization of AVP and c-Fos in PVN neurons may be associated with increased AVP release. It is also possible that increased neuronal activity in the PVN, after conditioning to dam, induced a pulse of endogenous AVP. AVP is involved in regulating affiliative behavior and attachment via the V1aR in the brain[7, 18]. Previous research has showed a positive correlation between social interactions and AVP mRNA expression in the PVN in mice[23]. The female′s role in lactation presumably makes her the dominant care provider. Previous study found that mandarin pups emitted more vocalizations and spent more time in contact, approaching, sniffing, climbing, inactive and walking near their mother than father[11]. Results from these studies might interpret why mother conditioning rather than father conditioning significantly enhanced AVP-IR expression in these pups. Here, increased AVP in pups may help strengthen infant-mother bonding. These results are different from our previous study where we found lower AVP expression in the PVN and SON after social conditioning[14]. This is likely due to the difference in the type of reinforcement where an adult was conditioned with unfamiliar conspecifics in previous study, while a pup was conditioned with their parents in the present study.

Reinforcers can interact with learning and memory systems by modulating or enhancing the information stored in each of the memory systems[24]. The process of attachment between parents and offspring involves mutual recognition[25]. AVP has been demonstrated to facilitate social recognition. AVP facilitates recall when given after an initial encounter, and the peptide is important for the consolidation of a social memory[26]. Furthermore, AVP′s role in social relationships reflects diverse social processes[27], thus AVP may play an important role in the infant′s preference for a parent because of its role in social memory.

Here, the pup was placed alone in chambers to separate them from their parents in the CK group. Previous studies in mandarin voles found that isolation from parents during PND14-18 is a stressor[28]. When animals are subjected to stress, corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH) is secreted from the hypothalamus, and CORT is secreted from the adrenal cortex to guard against stress as a result. Eight random days of brief maternal separation (15 min/day) induces higher plasma CORT levels in rats than controls[29]and 30 min of isolation from parents can increase CORT levels and ultrasonic calls after PND 14 in mandarin voles[28], demonstrating that pups experience stress upon being separated from their parents. On the other hand, stress responses are suppressed by parental interaction with pups. For example, presence of the mother suppresses CORT release in pups[30]and human fathers show lower CORT levels after 30min of father-child interaction[31]. Increased level of circulating CORT likely represents enhanced HPA activity that may lead to higher level of anxiety[32]. For pups in the CK group, elevated CORT levels may be tied to increased anxiety-related behavior. Proximity to the mother is influenced by stress and the more infants are stressed the more they remain close to their mothers[11]. The MC or FC group showed lower CORT levels compared to the CK group, indicating that a parent conditioning in chamber could buffer stressful response and anxiety in pups, and the mother may be more effective than the father in suppressing anxiety and CORT release because the levels of maternal care are higher than paternal care during pre-weaning days[3]. Dams lick and groom pups more frequently than sires, and this may alter the pattern of CRH in the pups to induce an attenuated response to stress[33]. Additionally, CORT are involved in regulating the mesencephalic dopaminergic system associated with reward[34]. In male prairie voles, increases in CORT are associated with higher levels of partner preference[20]. Thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that changes in stress-responsiveness may contribute to a pup′s preference to its parents.

In conclusion, our results showed that pup preference-like behavior to its parents was correlated with changes in AVP and CORT levels, and AVP and c-Fos expression levels were different between maternal and paternal conditioning. These findings suggested that AVP and CORT signals play important regulatory roles in reward associations between infants and their parents. Our study provid additional insights into the neurobiology of filial bonding.