粪肥施用土壤抗生素抗性基因来源、转移及影响因素*

苑学霞,梁京芸,范丽霞,王 磊,董燕婕,赵善仓

粪肥施用土壤抗生素抗性基因来源、转移及影响因素*

苑学霞,梁京芸,范丽霞,王 磊,董燕婕,赵善仓†

(山东省农业科学院农业质量标准与检测技术研究所/山东省食品质量与安全检测技术重点实验室,济南 250100)

随着新型抗生素开发速度的不断下降以及抗性基因(Antibiotic resistant genes,ARGs)的快速出现和传播,细菌抗药性和ARGs对公共健康存在威胁,被公认为当前全球亟待解决的难题。虽然土壤本底存在ARGs,但畜禽粪便施用等人类活动加速了ARGs在土壤环境中的扩散和传播。粪肥施入土壤后,其对土壤微生物的抗性选择压力及基因水平转移导致的ARGs扩散转移将持续存在。畜禽粪便中的抗性细菌所携带的ARGs、土壤中抗生素累积导致微生物产生的ARGs和粪肥刺激含有ARGs微生物的繁殖等均为土壤中ARGs的主要来源。土壤中ARGs可以向水体和农作物传移,并随着食物链向动物及人类传播。自然因素(温度、降水、时间和土壤类型)和人为因素(抗生素的含量和种类、粪便种类和处理方式、重金属含量及生物质炭添加)均会影响土壤中ARGs的持久和扩散。目前,粪肥施用土壤中ARGs污染对环境质量及健康的潜在影响并不完全清楚,建议加强模型建立、溯源、生物地理分布、从污染源向环境介质的转移规律、削减措施和机制等方面研究,以有效遏制ARGs在环境中的污染,真正做到畜禽粪便资源化、无害化利用。

抗生素;抗性基因;畜禽粪便;抗性细菌;自然因素;人为因素

抗生素的发明和使用是人类医学史上具有里程碑意义的成就,但由抗生素滥用而导致的大量抗药性致病菌的出现引起了人们对抗生素及抗性基因(Antibiotic resistant genes,ARGs)的广泛关注。随着抗生素的不断使用,微生物(包括病原菌和非病原菌)对抗生素的抗性逐年增加,对人类健康和环境安全构成了巨大的潜在危害[1]。欧洲每年大约2.5万人死于抗生素抗药细菌,美国每年至少200万人的疾病和2.3万人的死亡是由于抗生素抗药性导致的[2]。世界卫生组织(WHO)已将ARGs作为21世纪威胁人类健康的最重大挑战之一。2014年4月世界卫生组织发布首份全球114个国家抗生素抗药的监测报告。美国从1996年开始由美国疾病控制中心(CDC)、食品药品监督管理局(FDA)和农业部(USDA)三部门共同实施国家抗生素抗药性监测计划(National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System,NARMS)。我国于2016年由国家卫生计生委等14部门联合制定了《遏制细菌耐药国家行动计划(2016—2020年)》。抗生素和ARGs污染已经成为全球性的环境健康问题。

中国是畜禽养殖大国,全国各种规模畜禽粪便鲜重产量为16.29亿~32.64亿t[3]。畜禽粪便作为有机肥料广泛应用于农业生产中。随着集约化畜禽养殖业的发展,越来越多的抗生素用于畜禽疾病的防治。据估计,全球兽用抗生素2013年使用量约为13.1万t,到2030年将达到20.0万t[4]。2013年中国抗生素使用量为16.2万t,其中52%为兽用抗生素;在36种常见抗生素中,兽用抗生素的用量为7.8万t,占比高达84.3%[5]。这些兽用抗生素大多数不能被动物完全吸收,而是以原型或代谢物的形式排放至环境中,肉用动物使用的抗生素有30%~90%以母体化合物的形式随粪便排出体外[6],2013年中国36种常见抗生素排放量为5.4万t,分别排放至土壤(54%)和水体(46%)中,其中84.0%来源于动物排泄(猪:44.4%;鸡18.8%;其他动物20.9%),涉及的抗生素种类有磺胺类、四环素类、氟喹诺酮类、大环内酯类、-内酰胺类等[5]。土壤作为ARGs的重要储存库和介质,成为各国科学家关注和研究的热点。

1 抗生素的作用及抗性产生的分子机制

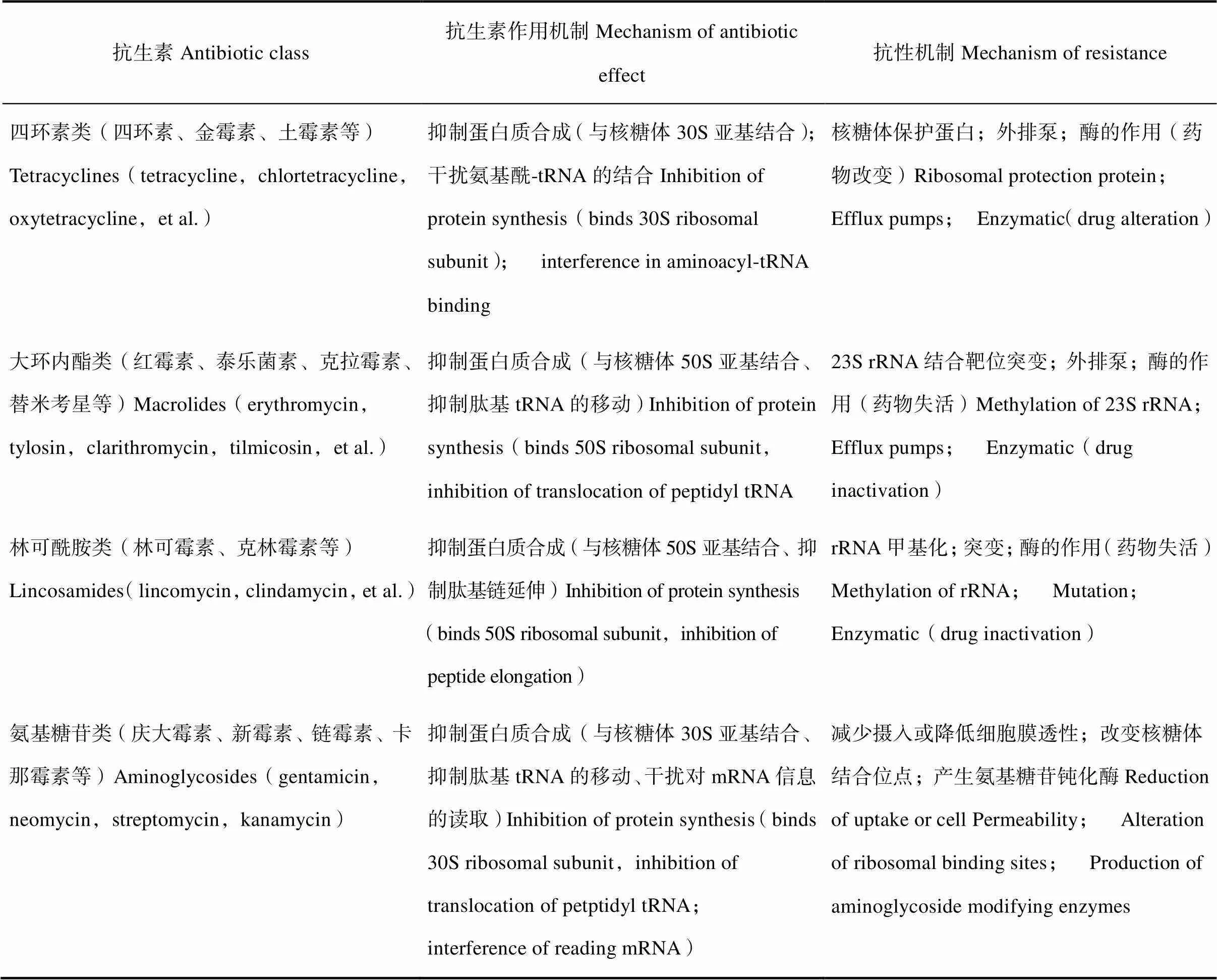

抗生素和微生物抗性之间是“侦查”与“反侦查”的关系。由于抗生素是微生物的代谢产物,此类微生物本身就具有抗药性,这种抗药性为固有抗药。另一方面,抗生素的滥用加速了ARGs与抗性细菌的产生和扩散。抗生素作用及抗性产生的分子机制[1,7]详见表1。

2 粪肥施用土壤中ARGs的来源

2.1 土壤中本底ARGs的存在

土壤中微生物数量庞大,种类极其丰富,是土壤中极为活跃的生物因子。尽管诸多研究表明人类活动与土壤中的ARGs相关,但是在未受人类影响的土壤中,微生物自身拥有丰富多样的抗药性及ARGs[8]。研究发现,在3万年前冻土中发现了β-内酰胺类、四环素类和糖肽类ARGs的存在[9];在被隔离400万年的洞穴中分离的细菌中也发现18个染色体抗药性元件[10]。以上皆说明土壤微生物中ARGs的存在早于人类使用抗生素。van Goethem等[11]对尚未有人类活动的17个南极土壤样品进行分析,发现了177种自然存在的ARGs,其中大部分ARGs编码一个或多个外排泵,常见的有β-内酰胺类、氯霉素类、氨基糖苷类ARGs。

2.2 动物粪便中的抗生素抗性细菌所携带的ARGs

动物粪便中的抗生素抗性细菌所携带的ARGs是土壤中ARGs的重要来源。由于抗生素的长期滥用,诱导动物体内产生ARGs,引发细菌抗药性。除此之外,为了增产,重金属作为动物生产所需要的微量元素,也被作为添加剂广泛添加至饲料中[12],引发了重金属和ARGs的共选择作用,加剧了动物肠道中ARGs的形成[13]。

表1 抗生素作用及抗性产生的分子机制

续表

Zhao等[14]发现猪饲料中抗生素以及重金属的添加会增加其肠胃微生物ARGs的丰度,ARGs的分布与微生物群落结构密切相关,其中拟杆菌门和厚壁菌门之间关系最为密切;ARGs群落变化由饲料中的抗生素和金属添加(31.8%)、肠道微生物群落组成结构(23.3%)及二者的相互作用(16.5%)导致。肉牛饲喂四环素及引起的其他因素可增加粪便中抗药性大肠肝菌的数量[15]。

越来越多的研究从畜禽粪便中检测到高丰度的ARGs,如四环素类ARGs:A、C、E、G、M、O、Q和T,磺胺类ARGs:1、2和3,喹诺酮类ARGs:B、S和D,链霉素类ARGs:A、B,氨基糖苷类ARGs:A,大环内酯类ARGs:B、F等[16-17]。畜禽粪便中存在丰富多样的ARGs,多种抗药机制并存已成为一种普遍现象。Qu等[18]对鸡盲肠中微生物进行检测,发现了大量的转座酶基因,这些转座酶在一定程度上促进了ARGs的水平转移,这也是鸡粪中抗生素ARGs丰度高的一个重要原因。

先进技术的发展为研究ARGs提供了更好的技术手段。采用高通量定量PCR技术在加拿大一个奶牛场的牛粪中发现114种ARGs,其中,大环内酯-林可酰胺-链阳菌素B类(MLSB)28种ARGs、四环素类21种ARGs、氨基糖苷类19种ARGs、多重抗药类18种ARGs、β-内酰胺类16种ARGs[19]。在澳大利亚一项研究中,鸡粪中检出127种ARGs、牛粪中检出109种 ARGs、猪粪中检出136种ARGs,其中,鸡粪中有19种、牛粪中有3种、猪粪中有22种,三种粪便共同存在的有86种[20]。这表明畜禽粪便是重要的ARGs储存库,粪便中ARGs的丰度可能与养殖场中抗生素使用情况和动物类型密切相关。

2.3 土壤中抗生素累积可能导致微生物产生ARGs

在多家养殖场的粪便中检出多种高浓度的兽用抗生素。Guo等[21]选取了江苏16家养殖场53个粪便样品发现,检出率最高的为四环素类药物,检出浓度为54.1~5 775.6 µg·kg–1,其次为喹诺酮类药物(8.4~435.6 µg·kg–1)、磺胺类药物(3.2~5.2 µg·kg–1)和大环内酯类药物(0.4 ~110.5 µg·kg–1)。Pan等[22]选取了山东21家典型集约化养猪场,采集并分析了126个猪粪样本的抗生素浓度,发现四环素类检出率为84.9%~96.8%,其中金霉素的检出浓度最高,达到764.4 mg·kg–1,是目前为止四环素类抗生素在猪粪中检测到的最高浓度,磺胺类抗生素的检出率为0.9%~51.6%,其中磺胺二甲嘧啶检出浓度最高,达到28.7 mg·kg–1。

随着粪便和污水作为肥料施入土壤,抗生素也随之进入土壤。在环境中,有的抗生素(如青霉素类)很容易降解,有的(如氟喹诺酮类、大环内酯类)可存在很久,容易扩散和累积[23]。在长江三角洲241个农田土壤均检出抗生素,其中四环素检出频率最高(99.6%)、其次为喹诺酮类(99.0%)和磺胺类(66.8%)[24]。在河北、河南、四川、江苏四省53个土壤中,96.23%的土壤检出抗生素,其中磺胺间甲氧嘧啶检出率最高(71.70%)、土霉素检出浓度最高(415.0 µg·kg–1)[25]。

关于抗生素浓度和ARGs的报道较多,但在同一时间和地点对这两个参数同时量化的研究较少。对截止2018年5月的42篇同时检测抗生素浓度和ARGs丰度的文献进行Meta分析,抗生素压力对ARGs丰度的增加作用显著,即使在抗生素浓度很低的水平下也是如此[26]。在长期施用四环素残留猪粪的土壤中发现,四环素残留量与四环素ARGs丰度存在着显著的正相关关系[27]。在长期施用牛粪和鸡粪的温室土壤中,抗生素残留量与ARGs丰度显著正相关[28]。有研究发现ARGs丰度对不同抗生素的响应不同,四环素类ARGsO、W、M与土霉素含量显著正相关,但与同为四环素类药物的四环素、金霉素和强力霉素的相关性不显著,磺胺甲嘧啶与磺胺类ARGs2相关性也不显著[29]。

2.4 粪肥施用后土壤微生物群落改变

即使施用不含抗生素的有机肥,也可以显著富集土壤中抗生素抗性微生物和ARGs,其原因是土壤养分的投入改变了土壤微生物群落结构组成,引起含有CEP-04基因的假单胞菌、含有β-内酰胺酶抗性的紫色杆菌和肺尖嗜冷杆菌的大量繁殖[30]。Han等[31]认为施用猪粪和鸡粪通过影响土壤的理化性质,增加土壤中细菌的丰度,进而影响土壤中ARGs和移动元件(Mobile genetic elements,MGEs)的丰度;46.3%的ARGs变异可以由细菌群落(27.6%)、MGEs(8.9%)、土壤理化性质(4.2%)、细菌群落+ MGEs(1.5%)、细菌群落+土壤理化性质(1.9%)、MGEs+土壤理化性质(1.4%)和细菌群落+土壤理化性质+MGEs(0.8%)解释。

3 粪肥施用土壤中ARGs分布及转移

3.1 粪肥施用土壤中ARGs分布

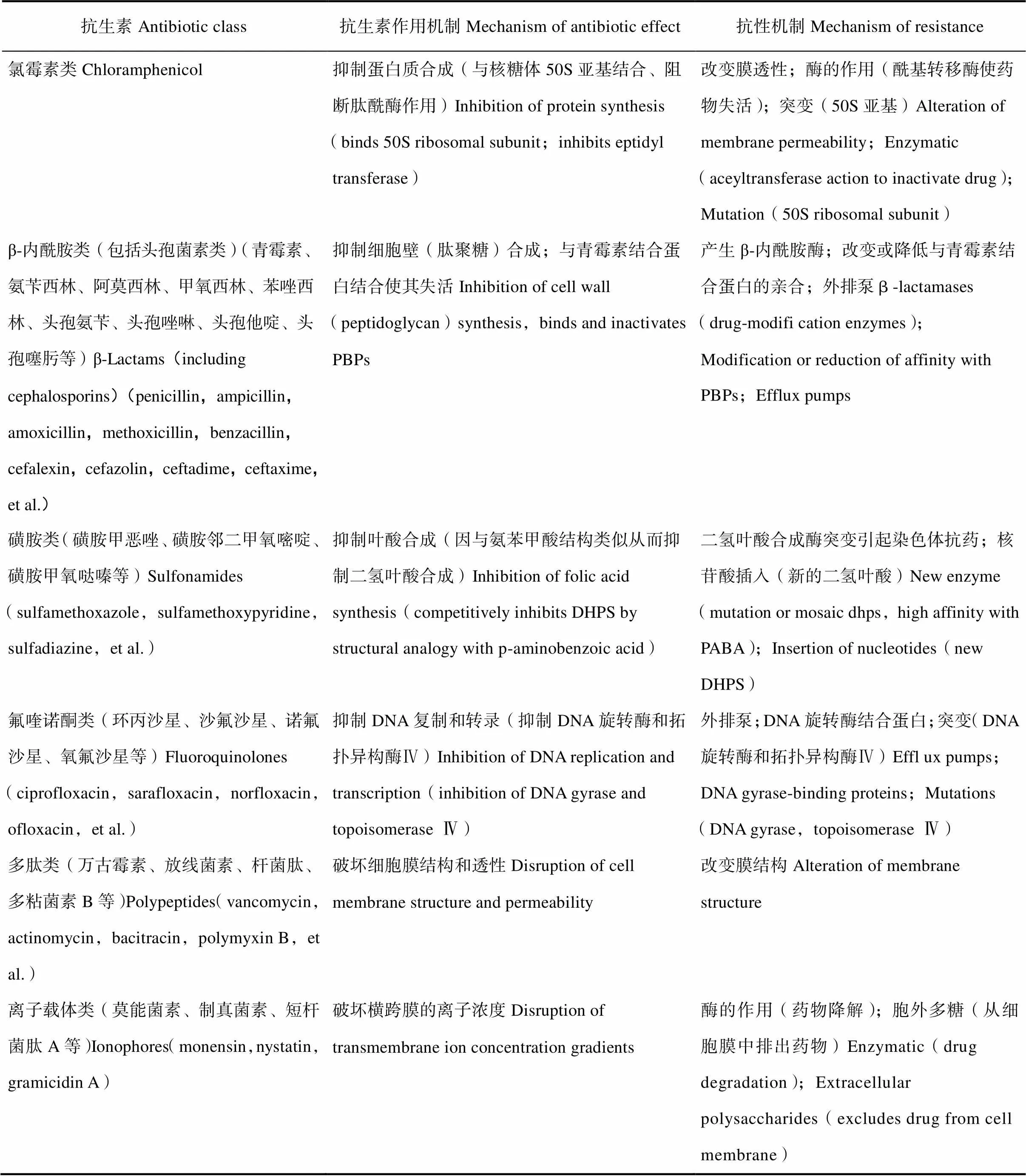

畜禽养殖业向土壤输入的ARGs不仅仅局限于养殖场内和养殖场周围的土壤中,它还将随着粪肥施用于农田中而传播至更远的地方。在不同国家和地区、施用不同类型肥料的土壤中检出多种多样的ARGs和MGEs(表2)。

表2 粪肥施用土壤中抗性基因(ARGs)和移动元件(MGEs)

注:—表示文献中未提及生长植物Note:— means that no plant information available

此外,粪肥施用对致病微生物及抗药性的影响更应该引起注意。Pornsukarom和Thakur[44]研究发现土壤和猪粪中沙门氏菌的检出率分别为10.69%和38.46%;美国北卡罗莱纳州的检出率(25.45%)极显著高于爱荷华州(2.73%);从猪粪及施用猪粪的土壤中分离出58.73%的沙门氏菌具有对三种或三种以上药物的多重抗药性。猪粪施用土壤中分离的产超广谱β-内酰胺酶大肠杆菌与猪粪中的基因相似度高于90%[45]。ARGs一旦存在于人类致病菌上,这些具有抗药性的致病菌就很可能随着粪肥的施加进入食物链,进而可能引发临床感染。总之,环境中的致病微生物所携带的抗药性及ARGs不仅是一个环境问题,更是关系到人体健康的公共卫生问题。

3.2 土壤中ARGs的转移

普遍认为,抗生素抗性细菌通过粪肥施用进入土壤,所携带的大量ARGs在环境中的持久性残留以及在不同介质中的转移、扩散较抗生素本身对环境的危害更大。

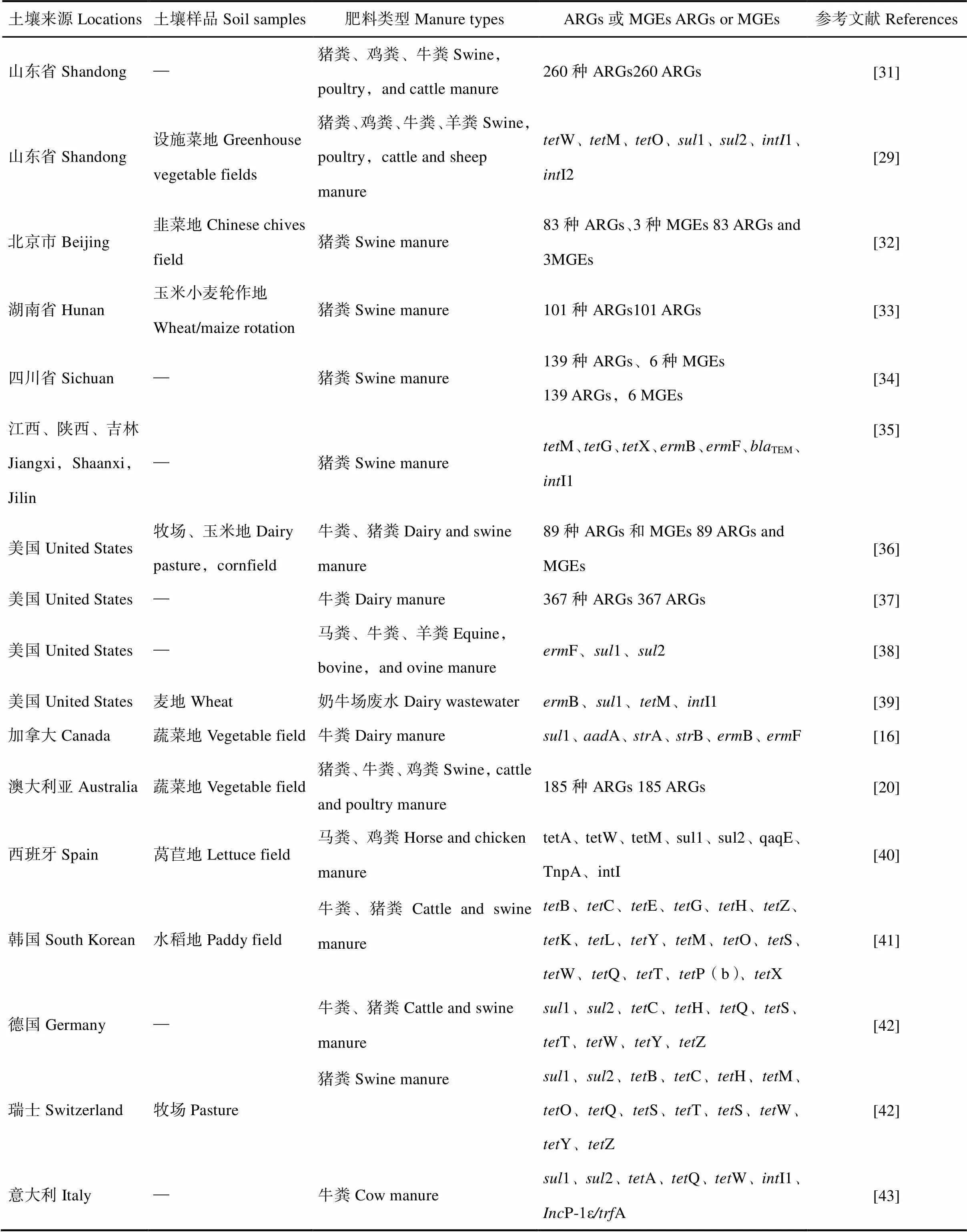

ARGs的传播扩散通过两种方式:垂直转移和水平转移。其中垂直转移是指亲代和子代之间通过繁殖发生的基因转移。水平转移是指同种或不同种属菌株之间通过转化、转导和接合等方式发生的基因转移[7]。但ARGs在土壤、水及植物中的转移分配比例及程度尚不清楚。抗性细菌和ARGs在环境中的存在及转移详见图1。

土壤和畜禽粪便中的细菌群落存在巨大差异,土壤中的微生物较粪便中的更具有竞争力[46],粪便中的细菌在土壤中的存活时间虽然仅有几周到几个月,但是基因从粪便抗药细菌到土壤土著细菌的水平转移会导致土壤中ARGs长期持留[30]。在施用猪粪的土壤中发现多重抗药沙门氏菌通过质粒介导ARGs的水平转移[47]。粪便能刺激抗生素ARGs在土壤中的水平转移,主要的宽宿主质粒如P-1和Q在粪便中丰度很高,质粒N和W也经常被检出,若ARGs在质粒中存在,质粒的多样性使ARGs能够在不同的细菌种属之间进行水平转移[48],导致ARGs更广泛迁移。此外,整合子是基因水平转移的遗传元件之一,是细菌基因组进化的热点,它可以通过基因盒的获得与重排进行基因水平转移。其中,一类整合子携带的ARGs盒主要编码与氨基糖苷类、β-内酰胺类和氯霉素抗性相关的ARGs[49]。

图1 抗性细菌和ARGs在环境中转移示意图[50]

土壤作为重要的ARGs储存库,其中部分抗药细菌及ARGs会随着雨水的淋洗、径流等进入水体中。水体环境是另一个重要的ARGs储存库,而农田的径流水是水体中ARGs的重要来源[51]。有研究发现,施用猪粪可显著增加径流水中Q、X、B、F的含量,并且Q、B、F受降雨的影响[52]。Fang等[53]发现养殖场中ARGs主要是通过养殖废水排放、粪肥施用转移扩散至溪水、沉积物和设施土壤中。

土壤中ARGs还会附着在农作物中随着食物链向人体及动物传播。生长在粪肥施用土壤中的蔬菜暴露于ARGs高风险中[16]。Wang等[54]在粪肥施用土壤、植物内生菌和叶际微生物中均检测到ARGs存在,这些抗性植物内生菌很可能来自土壤土著细菌,并在植物组织内定殖,促使ARGs从土壤转移至植物中,对人类健康存在潜在威胁。Marti等[55]在施用猪粪的土壤以及土壤上种植的蔬菜均检测到了多种ARGs,在施用新鲜猪粪的土壤中收获的蔬菜检测到一些独有的抗生素ARGs。因此,作为粪肥中ARGs和植物ARGs的介质,土壤中ARGs的研究就显得尤为重要。

4 粪肥施用土壤中ARGs持久性和传播扩散的影响因素

粪肥施用土壤中ARGs持久性和传播扩散的影响因素主要分为两个方面,一方面是自然因素:主要包括气候(温度、降雨)、时间和土壤类型等;另一方面是人为因素:主要包括抗生素的含量和种类、粪肥的种类和处理方式、重金属含量、生物质炭添加等。

4.1 自然因素

4.1.1 气候(温度、降雨) 关于气候对土壤中ARGs的影响研究较少,但是土壤中温度、含水量等均是影响土壤中微生物的重要因素,其对微生物群落的影响可能会影响土壤ARGs丰度。在长期施用四环素残留猪粪的土壤中发现,合适的气候条件对抗药菌和ARGs形成有较好的促进作用,秋季较夏季更适合抗药菌和ARGs形成[27]。此外,降雨影响携带ARGs的细菌生长和ARGs水平转移[38]。

4.1.2 时间 粪肥携带的细菌在土壤中的存活时间因条件的不同差异很大。以沙门氏菌为例,在低于0℃的土壤中沙门氏菌可存活6个月以上,0~5℃可存活小于等于28周,而30℃仅存活4周。虽然粪便耐抗生素细菌会死亡,但粪便抗药细菌携带的ARGs水平转移至土壤土著细菌中。Zhang等[56]研究发现施肥172 d后黄壤中ARGs的丰度增加,而在红壤和黑土中ARGs的丰度降至对照水平。也有研究表明,尽管粪肥施用土壤中ARGs的丰度随着时间的延长而减少,但是120d后,其丰度仍然较未施肥土壤的高[31]。Zhao等[29]研究了粪肥施用1 a到大于10 a设施蔬菜地中ARGs的分布,发现施肥年限对ARGs含量和丰度的影响并无明显趋势。

4.1.3 土壤类型 不同类型的土壤其理化性质、结构、微生物组成等各不相同,因此不同类型土壤具有不同的ARGs组。有研究认为氮元素对土壤ARGs含量有很大影响[57]。与土壤中的养分相比,细菌对粪肥施用土壤中四环素ARGs累积发挥更重要的作用[46]。中性pH、高含量有机碳的土壤中ARGs受粪肥施用的影响最小[35]。Zhang等[56]发现土壤类型显著影响粪肥施用后土壤中抗药细菌和ARGs动态变化,在红壤和黑土中ARGs的变化取决于微生物群落的变化,而在黄壤中基因水平转移是影响ARGs的主要因素。

多项研究认为土壤中细菌群落组成对粪肥施用土壤中ARGs组成的影响很大。在农田中变型菌门细菌影响ARGs的组成,而在草地中绿弯菌门和浮霉菌是主导菌[36]。Forsberg等[57]对18种农业和草地土壤进行18种抗生素抗性的功能元基因组筛选,发现细菌群落组成(而不是水平转移)是土壤中抗生素抗性的主要决定因素。因此,维持或增加土壤微生物的多样性可能对缓解土壤中ARGs的扩散和累积有效果。

4.2 人为因素

4.2.1 抗生素的含量和种类 关于土壤中抗生素和ARGs之间的关系在2.3中已做论述,但也许抗生素和ARGs的环境共存并不一定是单纯的因果关系。它们通常同时被排放至环境中,遵循类似的路径。但不同的是,抗生素在环境中可降解,而ARGs不是“可降解的污染物”,而是在环境中可自动复制、增殖或减少的元件,ARGs的持久性和扩散途径更加多样和复杂。

4.2.2 粪便种类和处理方式 作为一种常用的农业措施,粪肥施用会导致大量微生物(包括抗性细菌和潜在的人类病原菌)进入土壤。功能元基因组学分析表明,施用有机肥后肥料源ARGs占土壤中ARG总量的70%以上[58]。猪粪、牛粪、鸡粪是施用最广泛的三种粪肥类型,由于动物和饲养方式不同,不同动物粪便中含有不同ARGs。有研究发现粪便中ARGs丰度由高到低的顺序依次为猪粪、鸡粪、牛粪[20]。Peng等[59]发现粪肥施用30 a后,猪粪显著增加了土壤中ARGs丰度,而施用牛粪的作用不明显。土壤中携带ARGs的细菌生长和ARGs水平转移也受粪便类型的影响[38]。

好氧堆肥是畜禽粪便无害化处理和资源化利用的重要方式。Gou等[19]发现好氧堆肥可显著降低牛粪和土壤中ARGs的丰度和多样性,并且在施用堆肥土壤中ARGs与MGEs的相关性弱于施用新鲜粪便的土壤中。但也有研究发现堆肥处理增加了粪便中的X的丰度,但土壤中未变化,而在粪便和土壤中G均有增加[56]。

厌氧消化在畜禽粪便处理和沼气生产中有着广泛的应用。厌氧消化降低了沼气残渣中四环素ARGs和大环内酯类、林可酰胺类、链阳性菌素类(MLSB)ARGs;但磺胺类、氨基糖苷类和氟苯尼考、氯霉素和胺酰醇类ARGs增加了几十倍甚至几百倍[32]。长时间低溶氧可加速猪场粪水中ARGs的去除[60]。高固体厌氧消化过程中游离氨的不足和挥发性脂肪酸(特别是丙酸)的积累减缓了猪粪中ARGs的降低[61]。

4.2.3 重金属含量 为了增强畜禽防病能力、提高畜禽生长性能,重金属在规模化畜禽养殖中的滥用现象导致畜禽粪便中重金属富集。在猪粪堆肥过程中铜抗性基因、ARGs、I1间存在共生关系,其中,基因A、B、A、B及I1丰度降低,而基因A和A丰度升高;高浓度铜离子降低铜抗性基因、ARGs、I1的传播效率[62]。粪肥施用30年的土壤中Cu、Zn、Pb含量增加,并且与G、O、W、B(P)、1、2、B和F成显著正相关,表明重金属参与细菌抗药性共选择过程。而Cu、Zn、Pb含量与MGEsl1的正相关关系表明三种重金属可能参与ARGs的转移[59]。即使是亚剂量的重金属也会促进质粒介导的ARGs水平转移[63]。此外,纳米级铝也被发现能够引起ARGs的水平转移,对ARGs的接合、转化和转导过程均有促进作用,这与其影响细胞膜状态和调控基因表达有关,而正常铝对ARGs无影响[64]。

4.2.4 生物质炭添加 生物质炭是在无空气的情况下生物质热解过程中形成的一种富碳固体,通过参与π-π电子供体、受体表面与抗生素的相互作用,有可能降低土壤溶液中抗生素的浓度。在含有高丰度ARGs的有机肥污染土壤中,生物质炭的添加降低了土壤、生菜叶片和根系中ARGs的丰度[65]。但也有研究得出不同的结果:添加生物质炭30 d后土壤中ARGs显著降低,而60 d后,添加生物质炭的土壤中ARGs显著高于对照[66];添加生物质炭可显著降低土壤中ARGs的丰度,但在生长植物的土壤,生物质炭的作用不明显[67]。

5 研究展望

尽管多项研究证明抗生素在养殖业中的使用及畜禽粪便的施用促进了细菌抗药性的产生,但其对环境质量及健康的潜在影响并不完全清楚。由于抗生素使用和粪肥施用过程中一系列的相互作用,相关的非生物学和生物学机制非常复杂。虽然诸多研究认为选择性突变和基因水平转移机制是ARGs在环境中不同介质之间存在和转移的主要原因,但也不排除与环境中其他因素协同作用的可能。因此,有必要深入开展实地试验和模型建立工作,将其他生物和非生物参数(土壤动物、营养物质)、抗药性共同选择剂(多种重金属)和污染类型(污水、粪便污染、灌溉)等多种因素结合起来,避免由于数据来源、设计和方法不同带来的模型预测能力有限和不确定性。

由于ARGs本身是一种自然现象,环境中广泛存在抗药性本底值,因此难以区分、辨别由人类活动(如畜禽养殖)引起的抗药性和自然本底抗药性,对ARGs进行溯源成为一种新的挑战。因此,有必要对以下三方面进行深入研究:1)具有指示作用的ARGs;2)可能的潜在性基因宿主微生物;3)采用不同类别的ARGs建立模型,用于追溯抗生素抗药来源。

微生物功能基因与地理距离相关,具有生物地理上的地方特性。对于ARGs大尺度地理分布格局的研究可以增加人们对ARGs在生态系统中扩散机制的认识。对于ARGs是否显示出距离衰减关系,以及驱动微生物分类群落的生物地理学的四个基本过程(选择、漂移、扩散和突变)影响ARGs的生物地理模式需要深入研究。

随着科技的发展,高通量测序、生物信息学和现代统计分析技术的发展为多尺度、多层次研究ARGs的发生、转移和扩散途径及机制提供了科学手段。应该对ARGs从污染源向土壤、地下水、地表水及植物介质中的传播规律、削减措施及机制开展更深入研究,以期有效遏制ARGs在环境中的污染,真正做到畜禽粪便的无害化和资源化利用。

[1] Blair J M,Webber M A,Baylay A J,et al. Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nature Reviews Microbiology,2015,13(1):42—51.

[2] Kennedy D. Time to deal with antibiotics. Science,2013,342(6160):777.

[3] Xie G H, Bao W Q, Liu J J, et al. An overview of researches on livestock and poultry excreta resouce in China. Journal of China Agricultural University,2018,23(4):75—87. [谢光辉,包维卿,刘继军,等. 中国畜禽粪便资源研究现状述评. 中国农业大学学报,2018,23(4):75—87.]

[4] van Boeckel T P,Glennon E E,Chen D. Reducing antimicrobial use in food animals. Science,2017,357(6358):1350—1352.

[5] Zhang Q Q,Ying G G,Pan C G,et al. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China:Source analysis,multimedia modeling,and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environmental Science & Technology,2015,49(11):6772—6782.

[6] Heuer H,Schmitt H,Smalla K. Antibiotic resistance gene spread due to manure application on agricultural fields. Current Opinion in Microbiololgy,2011,14(3):236—243.

[7] Chee-Sanford J C,Mackie R I,Koike S,et al. Fate and transport of antibiotic residues and antibiotic resistance genes following land application of manure waste. Journal of Environmental Quality,2009,38(3):1086—1108.

[8] Cytryn E. The soil resistome:The anthropogenic,the native,and the unknown. Soil Biology & Biochemistry,2013,63:18—23.

[9] D'Costa VM,King C E,Kalan L,et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient. Nature,2011,477(7365):457—461.

[10] Pawlowski A C,Wang W,Koteva K,et al. A diverse intrinsic antibiotic resistome from a cave bacterium. Nature Communications,2016,7:Article number 13803.

[11] van Goethem M W,Pierneef R,Bezuidt OKI,et al. A reservoir of ‘historical’ antibiotic resistance genes in remote pristine Antarctic soils. Microbiome,2018,6(1):Article 40.

[12] Cang L,Wang Y,Zhou D,et al. Heavymetals pollution in poultry and livestock feeds andmanures under intensive farming in Jiangsu Province. Journal of Environmental Sciences,2004,16(3):371—374.

[13] Yazdankhah S,Rudi K,Bernhoft A. Zinc and copper in animal feed-development of resistance and co-resistance to antimicrobial agents in bacteria of animal origin. Microbial Ecology in Health & Disease,2014,25(1):Article 25862.

[14] Zhao Y,Su J Q,An X L,et al. Feed additives shift gut microbiota and enrich antibiotic resistance in swine gut. Science of the Total Environment,2018,621:1224—1232.

[15] Agga G E,Schmidt J W,Arthur T M. Effects of in-feed chlortetracycline prophylaxis in beef cattle on animal health and antimicrobial-resistant. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,2016,82(24):7197—7204.

[16] Tien Y C,Li B,Zhang T,et al. Impact of dairy manure pre-application treatment on manure composition,soil dynamics of antibiotic resistance genes,and abundance of antibiotic-resistance genes on vegetables at harvest. Science of the Total Environment,2017,581/582:32—39.

[17] Wang N,Guo X,Yan Z,et al. A comprehensive analysis on spread and distribution characteristic of antibiotic resistance genes in livestock farms of southeastern China. PLoS One,2016,11(7):e0156889.

[18] Qu A,Brulc J M,Wilson M K,et al. Comparative metagenomics reveals host specific metavirulomes and horizontal gene transfer elements in the chicken cecum microbiome. PLoS One,2008,3(8):e2945.

[19] Gou M,Hu H W,Zhang Y J,et al. Aerobic composting reduces antibiotic resistance genes in cattle manure and the resistome dissemination in agricultural soils. Science of the Total Environment,2018,612:1300—1310.

[20] Zhang Y J,Hu H W,Gou M,et al. Temporal succession of soil antibiotic resistance genes following application of swine,cattle and poultry manures spiked with or without antibiotics. Environmental Pollution,2017,231:1621—1632.

[21] Guo X Y,Hao L J,Qiu P Z,et al. Pollution characteristics of 23 veterinary antibiotics in livestock manure and manure-amended soils in Jiangsu Province,China. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part B,2016,51(6):383—392.

[22] Pan X,Qiang Z,Ben W,et al. Residual veterinary antibiotics in swine manure from concentrated animal feeding operations in Shandong Province,China. Chemosphere,2011,84(5):695—700.

[23] Grenni P,Ancona V,Barra Caracciolo A. Ecological effects of antibiotics on natural ecosystems:A review. Microchemical Journal,2018,136:25—39.

[24] Sun J,Zeng Q,Tsang D C W,et al. Antibiotics in the agricultural soils from the Yangtze River Delta,China. Chemosphere,2017,189:301—308.

[25] Wei R,He T,Zhang S,et al. Occurrence of seventeen veterinary antibiotics and resistant bacterias in manure-fertilized vegetable farm soil in four provinces of China. Chemosphere,2019,215:234—240.

[26] Duarte D J,Oldenkamp R,Ragas A M J. Modelling environmental antibiotic-resistance gene abundance:A meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment,2019,659:335—341.

[27] Zhang J,Yang X H,Ge F,et al. Effects of long-term appication of pig manure containing residual tetracycline on the formation of drug-resistant bacteria and resistance genes. Environmental Science,2014,35(6):2374—2380. [张俊,杨晓洪,葛峰,等. 长期施用四环素残留猪粪对土壤中耐药菌及抗性基因形成的影响. 环境科学,2014,35(6):2374—2380.]

[28] Li J,Xin Z,Zhang Y,et al. Long-term manure application increased the levels of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in a greenhouse soil. Applied Soil Ecology,2017,121:193—200.

[29] Zhao X,Wang J,Zhu L,et al. Field-based evidence for enrichment of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements in manure-amended vegetable soils. Science of the Total Environment,2019,654:906—913.

[30] Udikovic-kolic N,Wichmann F,Broderick N A,et al. Bloom of resident antibiotic resistant bacterial in soil following manure fertilization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,2014,111(42):15202—15207.

[31] Han X M,Hu H W,Chen Q L,et al. Antibiotic resistance genes and associated bacterial communities in agricultural soils amended with different sources of animal manures. Soil Biology & Biochemistry,2018,126:91—102.

[32] Pu C,Liu H,Ding G,et al. Impact of direct application of biogas slurry and residue in fields:analysis of antibiotic resistance genes from pig manure to fields. Journal of Hazardous Materials,2018,344:441—449.

[33] Xie W Y,Yuan S T,Xu M G,et al. Long-term effects of manure and chemical fertilizers on soil antibiotic resistome. Soil Biology & Biochemistry,2018,122:111—119.

[34] Cheng J H,Tang X Y,Cui J F. Effect of long-term manure slurry application on the occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes in arable purple soil(entisol). Science of the Total Environment,2019,647:853—861.

[35] Sui Q,Zhang J,Chen M,et al. Fate of microbial pollutants and evolution of antibiotic resistance in three types of soil amended with swine slurry. Environmental Pollution,2019,245:353—362.

[36] Chen Z,Zhang W,Yang L,et al. Antibiotic resistance genes and bacterial communities in cornfield and pasture soils receiving swine and dairy manures. Environmental Pollution,2019,248:947—957.

[37] Chen C,Pankow C A,Oh M,et al. Effect of antibiotic use and composting on antibiotic resistance gene abundance and resistome risks of soils receiving manure-derived amendments. Environment International,2019,128:233—243.

[38] Fahrenfeld N,Knowlton K,Krometis L A,et al. Effect of manure application on abundance of antibiotic resistance genes and their attenuation rates in soil:Field-scale mass balance approach. Environmental Science & Technology,2014,48(5):2643—2650.

[39] Dungan R S,McKinney C W,Leytem A B. Tracking antibiotic resistance genes in soil irrigated with dairy wastewater. Science of the Total Environment,2018,635:1477—1483.

[40] Urra J,Alkorta I,Lanzén A,et al. The application of fresh and composted horse and chicken manure affects soil quality,microbial composition and antibiotic resistance. Applied Soil Ecology,2019,135:73—84.

[41] Kim S Y,Kuppusamy S,Kim J H,et al. Occurrence and diversity of tetracycline resistance genes in the agricultural soils of South Korea. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International,2016,23(21):22190—22196.

[42] Schmitt H,Stoob K,Hamscher G,et al. Tetracyclines and tetracycline resistance in agricultural soils:Microcosm and field studies. Microbial Ecology,2006,51(3):267—276.

[43] Chessa L,Jechalke S,Ding G C,et al. The presence of tetracycline in cow manure changes the impact of repeated manure application on soil bacterial communities. Biology and Fertility of Soils,2016,52(8):1121—1134.

[44] Pornsukarom S,Thakur S. Assessing the impact of manure application in commercial swine farms on the transmission of antimicrobial resistantin the envrionment. PLoS One,2016,11(10):e0164621.

[45] Gao L,Hu J,Zhang X,et al. Application of swine manure on agricultural fields contributes to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing escherichia coli spread in Tai'an,China. Frontiers in Microbiology,2015,6:Article 313.

[46] Peng S,Zhou B,Wang Y,et al. Bacteria play a more important role than nutrients in the accumulation of tetracycline resistance in manure-treated soil. Biology and Fertility of Soils,2016,52(5):655—663.

[47] Pornsukarom S,Thakur S. Horizontal dissemination of antimicrobial resistance determinants in multipleserotypes following isolation from the commercial swine operation environment after manure application. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,2017,83(20):01503—01517.

[48] Palmer K L,Kos V N,Gilmore M S. Horizontal gene transfer and the genomics of enterococcal antibiotic resistance. Current Opinion in Microbiology,2010,13(5):632—639.

[49] An X L,Chen Q L,Zhu D,et al. Distinct effects of struvite and biochar amendment on the class 1 integron antibiotic resistance gene cassettes in phyllosphere and rhizosphere. Science of the Total Environment,2018,631/632:668—676.

[50] Huijbers P M,Blaak H,de Jong M C,et al. Role of the environment in the transmission of antimicrobial resistance to humans:A review. Environmental Science & Technology,2015,49(20):11993—12004.

[51] Marti E,Variatza E,Balcazar J L. The role of aquatic ecosystems as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance. Trends in Microbiology,2014,22(1):36—41.

[52] Joy S R,Bartelt-Hunt S L,Snow D D,et al. Fate and transport of antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistance genes in soil and runoff following land application of swine manure slurry. Environmental Science & Technology,2013,47(21):12081—12088.

[53] Fang H,Han L,Zhang H,et al. Dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes and human pathogenic bacteria from a pig feedlot to the surrounding stream and agricultural soils. Journal of Hazardous Materials,2018,357:53—62.

[54] Wang F H,Qiao M,Chen Z,et al. Antibiotic resistance genes in manure-amended soil and vegetables at harvest. Journal of Hazardous Materials,2015,299:215—221.

[55] Marti R,Scott A,Tien Y C. Impact of manure fertilization on the abundance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and frequency of detection of antibiotic resistance genes in soil and on vegetables at harvest. Applied and Environmental Microbiology,2013,79(18):5701—5709.

[56] Zhang J,Sui Q,Tong J,et al. Soil types influence the fate of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes following the land application of sludge composts. Environment International,2018,118:34—43.

[57] Forsberg K J,Patel S,Gibson M K,et al. Bacterial phylogeny structures soil resistomes across habitats. Nature,2014,509(7502):612—616.

[58] Jian Q S,Bei W,Xu C Y,et al. Functional metagenomic characterization of antibiotic resistance genes in agricultural soils from China. Environment International,2014,65(1):9—15.

[59] Peng S,Feng Y,Wang Y,et al. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes in soils after continually applied with different manure for 30 years. Journal of Hazardous Materials,2017,340:16—25.

[60] Ma Z,Wu H,Zhang K,et al. Long-term low dissolved oxygen accelerates the removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in swine wastewater treatment. Chemical Engineering Journal,2018,334:630—637.

[61] Sui Q,Meng X,Wang R,et al. Effects of endogenous inhibitors on the evolution of antibiotic resistance genes during high solid anaerobic digestion of swine manure. Bioresource Technology,2018,270:328—336.

[62] Yin Y,Gu J,Wang X,et al. Effects of copper addition on copper resistance,antibiotic resistance genes,andl1 during swine manure composting. Frontiers in Microbiology,2017,8:Article 344.

[63] Zhang Y,Gu A Z,Cen T,et al. Sub-inhibitory concentrations of heavy metals facilitate the horizontal transfer of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance genes in water environment. Environmental Pollution,2018,237:74—82.

[64] Ding C,Pan J,Jin M,et al. Enhanced uptake of antibiotic resistance genes in the presence of nanoalumina. Nanotoxicology,2016,10(8):1051—1060.

[65] Duan M,Li H,Gu J,et al. Effects of biochar on reducing the abundance of oxytetracycline,antibiotic resistance genes,and human pathogenic bacteria in soil and lettuce. Environmental Pollution,2017,224:787—795.

[66]Cui E P,Gao F,Liu Y,et al. Amendment soil with biochar to control antibiotic resistance genes under unconventional water resources irrigation:Proceed with caution. Environmental Pollution,2018,240:475—484.

[67] Chen Q L,Fan X T,Zhu D,et al. Effect of biochar amendment on the alleviation of antibiotic resistance in soil and phyllosphere ofL. Soil Biology & Biochemistry,2018,119:74—82.

Effects of Manure Application on Source and Transport of Antibiotic Resistant Genes in Soil and Their Affecting Factors

YUAN Xuexia, LIANG Jingyun, FAN Lixia, WANG Lei, DONG Yanjie, ZHAO Shancang†

(Institute of Quality Standard and Test Technology for Agro-products, Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Test Technology on Food Quality and Safety, Jinan 250100, China)

With new antibiotics slowing down in development and antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) popping up and spreading rapidly, antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) and ARGs have become imminent threats to public health and a global problem urgently calling for solution. Nowadays, the industry of livestock breeding still abuses the use of veterinary antibiotics in concentrated feeding operation in an attempt to improve growth and control diseases. It is estimated that approximately 30%~50% of the administered antibiotics are excreted with waste instead of being absorbed by animals. Manure is commonly used as a substitute for inorganic N and P fertilizers for agricultural crops, especially in organic farming. In 2013, a total of 54 000 tons of 36 antibiotics was excreted in China, 54% into the soil and 46% into the water environment. The antibiotics involved include sulfonamides, tetracycline, fluoroquinolones, macrolides, β-lactam, etc. The ARGs contained in the ARB excreted with manure, generated in microbes as a result of accumulation of antibiotics in soil, and multiplied with the proliferation of ARGs-containing microbes stimulated by manure are the main sources of ARGs in the soil. Bacterial communities in manure and in soil vary sharply in structure. The bacteria in feces can survive in soil for weeks to months, depending on soil and environment, however, horizontal gene transfer from these bacteria to indigenous soil bacteria might rely on persistence of ARGs in soil. As one of the largest and most diverse microbial habitats on earth, soil has been the source of most discovered ARGs, supplying ARGs to water environment, crops, and animals and human through food chain. Once ARB and their corresponding suite of ARGs enter the soil, water and crops, their persistence and fate depend on nature and viability status of their host bacteria and their living environment. Both natural factors, like temperature, rainfall, time and soil type, and human factors, like content and specie of antibiotic, type and treatment of manure, content of heavy metal and biochar addition, could affect persistence and diffusion of ARGs in soil. However, the impacts of manure application contaminating the soil with ARGs on environmental quality and human health still remain unclear. It is, therefore, suggested that studies should be intensified on modelling, source tracing, biogeographical distribution, rules of ARGs transferring from sources to environmental media, measures to reduce and mechanisms of reducing the transfer, which will help to recycle animal waste safely and control pollution of ARGs in the environment effectively.

Antibiotics; Antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs); Livestock feces; Antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB); Natural factor; Human factor

X171.5

A

10.11766/trxb201903110049

苑学霞,梁京芸,范丽霞,王磊,董燕婕,赵善仓. 粪肥施用土壤抗生素抗性基因来源、转移及影响因素[J]. 土壤学报,2020,57(1):36–47.

YUAN Xuexia,LIANG Jingyun,FAN Lixia,WANG Lei,DONG Yanjie,ZHAO Shancang. Effects of Manure Application on Source and Transport of Antibiotic Resistant Genes in Soil and Their Affecting Factors[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica,2020,57(1):36–47.

* 国家自然科学基金项目(41907073)和国家重点研发计划项目(2016YFD0501407,2016YFE0109200)资助Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(No. 41907073)and the National Key Research and Development Program of China(Nos. 2016YFD0501407 and 2016YFE0109200)

,E-mail:shancangzhao@126.com

苑学霞(1980—),女,山东潍坊人,博士,副研究员,从事农业环境安全与风险评估研究。E-mail:xuexiayuan@163.com

2019–03–11;

2019–06–27;

2019–07–18

(责任编辑:陈荣府)