我们的生活

张利/ZHANG Li

作者单位:清华大学建筑学院/《世界建筑》

伯特兰·罗素在其浩瀚的《西方哲学史》中曾写道:“社区凝聚力是(文明演进的)必要条件,不过它从来不能单纯靠理性的方式加以保证。每个社区都必须面对两种截然不同的危险:一是对传统的盲目依赖与对教条的僵化执行所导致的裹足不前,二是对外来侵袭的顺从以及对个人主义的膨胀所导致的分崩离析。”在21世纪全球化达到如此程度的今天,当我们的话题指向的是新兴经济体的社区时,不难发现,这些社区所面对的基本风险仍然未变,只不过从某种程度上讲,今天的风险更多属于第二种。

联合国开发计划署网站近期赫然把“我们今天的生活方式——设计更繁荣与公平的城市生活”放在头条的标题位置,这与其说是一种温和的倡议,还不如说是一种紧迫的呼吁。无独有偶,第17届威尼斯国际建筑双年展的主策展人、MIT建筑学院院长哈希姆·萨尔基斯把今年展览的总主题定义为“我们如何共同生活”,邀请建筑师们面对加剧的割裂与不均,探讨人类如何实现真正的共居。一再而三,自2019-2020年之交起在我国及世界各地陆续出现的COVID-19疫情以及人们的勇敢抗疫故事,也从另一个方面给予了我们提醒与启示:即使在技术高度发展的当下,我们的生命健康仍然是不断受到挑战的,而保证我们的个体得以平安应对这些挑战的基地正是我们的群体所属的社区。可以说,今天的建筑学在我们的生活中所担当的使命,根本不是修饰浮华与壮丽的锦上之花,而是解决呼吸与食寝的燃眉之急。

然而,20世纪至今主导的建筑学观念、特别是后工业时代以来的建筑思潮与建筑教育并未对建筑服务于社区生活提供多少真正的帮助。刻薄地说,我们甚至可以认为,建筑学要想切实解决生活的燃眉之急,首先应当进行的恰恰是对自身误区(至少是近半个世纪来的自身误区)的反思。

以建筑的名义而有意无意传播的伪善是值得反思的——它发起于后工业时代早期建筑师的个人英雄主义,峰值于社交媒体指数增长的21世纪初。这种实践把明星的救世主情结、公众的同情心、大灾难或不幸者遭遇的悲剧性、社会新闻的时效感完整地组织到一个个建筑的故事里,宛如一幕幕令人难忘的舞台片断,其主角是度众生于水火的拯救者——明星建筑师,其配角是受众无法拒绝的弱势人群——儿童、妇女、老人、乡村的低收入者、种族歧视的受害者、战乱下的流离失所者,等等。这些带有强烈叙事性的建筑往往具有动人的视觉属性(特别是因弱势人群的生活场景而平添的暗色“异样风情”),易于成为网络上的热点和奖项中的宠儿,却难于对它们所宣称服务的群体产生持久的正向影响,难于对它们所坐落的社区的日常需要形成实质性的积极回应。1940年代,哈桑·法赛为安置卢克索的盗墓者而设计的新古尔纳村——一个公益社区建筑的著名早期案例——在今天被当地的社区居民所废弃,不得不由开罗的学者来呼吁将其作为文化遗产保护,这里所反映出的“明星”社区建筑对实际社区的脱离,是发人深省的。

以建筑的方式所推进的技术进化笃信是值得反思的——它基于工业革命甚至早至启蒙运动时期的一种盲目乐观,即现有的困难与不幸必将随新技术的到来迎刃而解。这种被瓦尔特·本雅明称为“幻象”的“未来技术将自动地为我们提供富足与健康”的方法论自CIAM初期以来一直伴随着我们的城市与建筑,重复着工具理性与“被完美计划的”生活之间的机械嫁接,至今未去。在它的作用下,具体的社区被不加区别地代入到抽象的理想工程化模型中——从工业时代的零件、后工业时代的集成组件到网络时代的数据集群——而社区的解决方案也相应的来自于工业、后工业或是网络的解决方案系统。个体的、有差异的人,特别是人体与空间的互动这一本初的建筑学命题被一波又一波的技术更新光环所边缘化。1980年代,由建筑师韦伯与布兰德设计的亚琛工业大学附属医院在开业之初,曾因先进的复合管道体系与完美的模块化动线逻辑而被认为是疗学研一体的未来综合医疗社区的最佳代表;而在今天,它的低矮层高、阴暗光线与迷宫走廊是病患空间心理关怀缺失的典型案例。类似的事例还很多,遍布于不同技术时代与不同发展程度的地区之中。

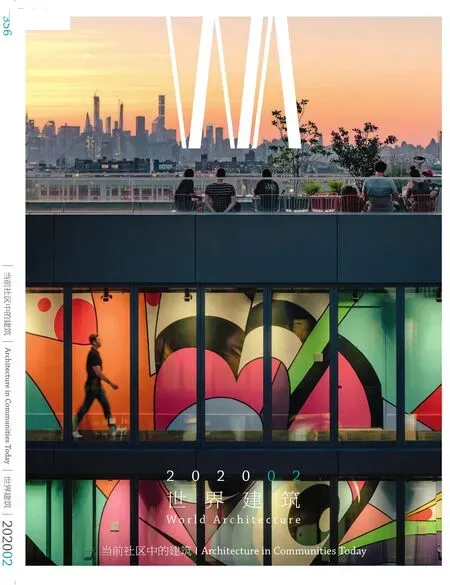

建筑师要服务于我们今天的社区生活,必须理解我们今天的社区生活,必须具备抵达普通社区居民的共情能力。本期《世界建筑》的初衷是想借助对各国社区建筑案例的审视寻找未来社区建筑学的启示。有趣的是,在对所集案例整理之后,我们发现它们所呈现的实际是一个明显的过渡期图景:我们的一只脚还停留在对20世纪英雄主义与进化论遗产的改良,另一只脚已经迈入了21世纪面向可持续性与社会公平的积极建构。如果这幅图景令人略感混杂的话,请至少相信它是真实的:有花枝招展的昂贵地产所作出的高显现度的社区姿态;有似曾相识的公共艺术解决社会问题假说;有知难而进的立体城市主题再现;有唤人同情的弱势人群故事,等等。但最重要的,是还有3个同样来自热带亚洲的作品,它们都同样的“其貌不扬”却“其质华光”:一个把泰式的幽默与乐观融入立面的公共空间化;一个把遗产保护的马来西亚式谦逊务实与吉隆坡的都市生活方式恰切匹配;一个则坚持新加坡领先的城市环境理念,以之构建社区公共性的基础空间逻辑。

实际上,在任何时候有机会讨论建筑与社区生活的话题,都是令人感激的,其后的原因也是不言而喻的。日前,一段由意大利南方团队Casa Surace制作的抗疫视频《冠状病毒:来自奶奶的建议》抚慰了全球数百万人的心。其间,那位经常现身于Casa Surace作品中的风趣老妪慈祥地告诉网络另一端的“孩子们”不要担心,而要担起自己的责任——医学未竟之处,还有文明在守望——这真是了不起的表达。建筑的意义,难道不正是通过建造活动连接人与自然、连接人与人、连接社区肌理,从而不论技术与经济水平、不论种族与性别归属、不论传统与信仰差异,参与构筑最基本的文明守望么?这难道不正是建筑学数千年来一直作为,并将在未来继续作为改变世界的正向力量的一份殊荣么?

感谢谢玉华女士,是她的热忱与帮助使本期《世界建筑》成为可能。□

In his epic A History of Western Philosophy, Bertrand Russell wrote: "Social cohesion is a necessity, and mankind has never yet succeeded in enforcing cohesion by merely rational arguments. Every community is exposed to two opposite dangers: ossification through too much discipline and reverence for tradition, on the one hand; and on the other hand, dissolution, or subjection to foreign conquest,through the growth of individualism and personal experience that makes cooperation impossible." One does not need to be a philosopher to see that today, with globalisation a fully-grown reality in the 21st century, our communities, those in emerging economies, in particular,are still exposed to these two dangers. The only difference is that to most communities, the second danger might be more urgent than the first.

On the United Nations Development Programme website, the front page headline is given to "The way we live now: Design for a prosperous and just urban life". It is widely accepted that this call is not a tentative motion for the ideals, but an urgent campaign for the fundamentals. UNDP is not alone in this regard. Hashim Sarkis, Dean of MIT SAP and the curator of La Biennale di Venezia 2020, unmistakably names the topic for this year as "How Will We Live Together", launching this enquiry on a "new spatial contract... in the context of divide and inequalities", urging architects to "imagine spaces in which we can genuinely live together." What has happened since the turn between 2019 and 2020,namely the COVID-19 outbreak, first in China, then in many other countries, reminds us even more through the touching stories of human difficulties and courage how precious our communities can be. In spite of all the technological advancements we are celebrating today, our communities are still vulnerable under emergencies, and must be cherished since they are the harbours in which we protect our loved ones. Architecture can certainly do more to improve our way of life today, not through spectacles, but through necessities.

Sadly, persisting architecture beliefs since the 20th century, professional or pedagogical, particularly those in the post-industrial age, have not helped much in making architecture more relevant to the necessities of our time.Cynically speaking, to make architecture work for our way of life, we may need to deconstruct some of the biggest myths in architecture first.

There has been a myth about the heroism of the individual architect saving entire communities, carrying with it de-facto hypocrisy in the name of architecture.It can be traced back to the early proliferation of star architects, and peaks at the time of social media boom in the current century. It combines the ego of the architect,sympathies from the public, tragedies of disasters and human miseries, and the topicality of journalism into architectural stories, one after another, like episodes of stage dramas. The protagonists are certainly architects the saviours, with supporting characters being the saved: children, women, the elderly, low-income farmers,victims of discrimination, refugees from warzones, etc.Both powerful in narratives and in visuals (especially helped by the dark exoticness of the living environment of the saved), projects of this kind collects online clicks and claims award titles in sweeping manners. Yet one thing they are weak at is to provide a long-lasting positive effect in the communities they serve since their original purpose was to showcase architectural hypotheses rather than meeting genuine local demands. Hassan Fathy's New Gourna for tomb robbers in Luxor was a widely celebrated case when it was completed in the late 1940s.The fact that it has been abolished by the community it meant to serve seventy years later is heartbreaking. The attempt from the academics in Kairo to preserve the work as a cultural heritage only makes it more unsettling.

There has been a myth about technological innovation being the panacea. Rooted in a blind optimism at the height of the industrial revolution (or even in the late enlightenment), it assumes that all our troubles today will be tackled by technological advancements tomorrow. Precisely denounced by Walter Benjamin as"phantasmagoria", such beliefs as "science and technology will serve all our needs automatically and abundantly"have found ways into all corners of our urban and architectural practice since the time of CIAM. They have been, and are still very much the mindsets behind the technological rationalism with which our urban life is being planned. Under this rationalism, our life is collectively mapped through engineering models, from the mechanic components of the industrial time to the prefab chunks of the post-industrial, to the data clusters of the internet. Solutions to our issues, unsurprisingly,also are built upon analogies of such. The uniqueness of individuals is overlooked. The poetic relationship between the human body and space, a quintessential preoccupation of the whole story of architecture,is continuously marginalised by wave after wave of technological hypes. In 1982, when the technologically accomplished, radically designed the Uniklinikum Aachen by Weber Brand & Partner opened, it was hailed as an exemplary model for future medical communities,and its modular space following the complication of integrated pipeline systems an ideal for all buildings with complex functions. Today, its low floor-to-floor clearance,awkward daylighting, and labyrinth-like circulation make a good example of negative patient psychological impact.Similar cases can be found in all time periods of recent technological advancements, and all regions of various developing levels.

It is fair to say that if we the architects are to serve our community life, we need to understand it first.Empathy is indispensable. The original intention of this WA number is to look for hints of what architecture can do to our future urban life. Interestingly, after sorting our the projects we have collected, we are finding rather a picture of transition in which one of our feet is still lingering in the heroic and Darwinian past, and the other already stepping into the more environmentallyfriendly and equal future. Do pardon us if you find the message of this picture blurry, because it is true. We have got some flamboyant statements of willingness to work for community in high-price, high-density residential projects. We have got some not-unfamiliar implementations of solving social problems through art.We have got some persevering adoptions of the 3D city ideal. We have got a number of narratives of helping the underprivileged as well. But most importantly, we have got three inspiring projects from tropical Asia, equally modest in their appearances, equally impressive in their design intrigue: a Thai treat of humour and optimism through the façade-as-public-space strategy; a Malaysian coupling of problem-oriented restoration and vibrant Kuala Lumpur life; a Singaporean manifest of green city as the ideological framework of community space.

To be honest, we are thrilled by and feel grateful for every opportunity of investigating architecture and community. The reason is self-evident. A few days ago,a YouTube video by Casa Surace, I Consigli di Nonna sul Coronavirus (Grandma's advice on Coronavirus) went viral and won the hearts of millions. In that video, the funny Italian grandma (who appears in a number of Casa Surace videos) spoke with great compassion to her young audience, telling them not to worry, but to stand up and take responsibilities: "What medicine can't solve, civility can." What a brilliant statement! Isn't it exactly the meaning of architecture to connect people,community and nature, to form a common base of civility disregarding all differences in knowledge, wealth, race,gender and belief? Isn't this a unique honour awarded to the profession of architects, for thousands of years already and for thousand of years to come?

Our special thanks to Ms. Fay Cheah, whose passion and help make this WA number possible.□