Monetary Policy Making and the Jackson Hole Symposium

By Gao Zhanjun

T he annual US Federal Reserve's Jackson Hole Economic Symposium concluded recently, and the topic “Challenges for Monetary Policy” seemed particularly appropriate. These are challenging times indeed amid weaker global growth and a spike in trade tensions. One of the key takeaways from the latest gathering of economic and financial heavyweights is that as far as the Fed is concerned the US economy is in fairly good shape - despite an inversion of interest rates - normally a reliable sign of recession ahead. The key task for the Fed, it seems, is sustaining the economic expansion, which has already powered ahead for more than a decade. And in the eyes of the Fed, trade policy - read that mostly as the trade war with China - is the main challenge rather than interest rates.

Once again major central bankers took the stage. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and Bank of England Governor Mark Carney both used some of their time to address trade policies and trade tailwinds for the economy.

But before we delve more closely into the current challenges and the policy responses, let us first examine this most prestigious gathering of the men and women tasked with keeping the global monetary system running smoothly. Why does this meeting get so much attention from the world's financial markets? How did Jackson Hole become the premier meeting for policy makers? Just who are these policy insiders, economists, financial market participants, and government representatives who gather in this idyllic retreat to discuss key longterm policy issues?

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City began hosting the conference at the Jackson Lake Lodge in Wyoming more than four decades ago. All 12 of the Fed's district banks organize research conferences, but only Jackson Hole becomes the Davos for central bankers.

The Symposium began in 1978. In 1982 the conference permanently moved to Jackson Hole and persuaded Paul Volcker, thenchairman of the Fed and a keen flyfisherman, to attend. At that time, Volcker's battle against inflation was putting the economy into a recession and left him fighting critics from all sides. He might have seen this meeting as a welcome relief, though it turned out to be no vacation.

Jackson Hole is a valley between the Teton Mountain Range and the Gros Ventre Range in Wyoming. In a book entitled In Late August, which introduces the history of this longstanding central banking symposium, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City depicts Jackson Hole this way: “Jackson Hole's awe-inspiring and isolated nature provides the ideal environment for symposium attendees to discuss economic policy issues away from daily pressures and distractions. At the symposium, barriers are removed and participants engage with each other in a way that isn't always possible at other gatherings, perhaps due to Jackson Hole's remote setting, no-frills location and the small number of participants.”

The ideal outdoorsy location and Volcker's regular attendance attracted other policymakers and made the event an unequalled gathering for heavy hitters in the economic policy realm. The goal of the symposium was to set up conditions of lively debate in an informal setting. The topic for each annual symposium is chosen by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, but the focus has always been purely on central banking, and it asks experts to write papers on related subtopics, including inflation, labor markets, international trade, economic growth, financial stability, and, of course, monetary policy. Though the discussions are heavily weighted towards academic analysis, central bankers also use this important gathering to indicate major changes in monetary policy.

To foster open discussion, attendance at the event is limited and by invitation only. Attendees are selected based on each year's topic with consideration for diversity in region, background and industry. About 120 people attend in a typical year (See Chart 1). According to Vincent Reinhart, a former Fed official who is now with BNY Mellon Asset Management, market participants have gone from 27% of attendees in 1982 to 3% in 2013. Their spots have been taken by foreign central bankers, who grew from 3% to 31%, and reporters, who went from 6% to 12% (The Economist, Aug 21st, 2014). Throughout the event's history, attendees from 70 countries have gathered to share their diverse perspectives.

The Jackson Lake Lodge is a National Park Service facility that does not have any resort-like amenities such as a spa, exercise room or salon. The author once stayed in a cabin at the resort, and foud it very rustic but comfortable. Throughout the conference, there is no special consideration from the Lodge, which still remains open to the public. All symposium participants pay a fee to attend, and the funds are used to recover event expenses.

The discussions are not only academic but at times they offer important signals on policy shifts. Over the past 42 years at the Jackson Hole Symposium, there have been numerous indications of future policy moves alongside a raft of interesting anecdotes. Below are some highlights.

—The theme for the 2007 symposium “Housing, Housing Finance and Monetary Policy” was viewed by some invitees as unsuitably boring, unimportant, and irrelevant at the time of its announcement. However, by the time the event kicked off in late August, the housing market had collapsed, making it the hottest topic of the financial world.

—In August 2010, then-chairman Ben Bernanke spoke of reasons and objectives for using unconventional monetary policy to provide additional stimulus. Three months later, the Fed announced a second round of quantitative easing, QE2.

—In a speech at the 2012 symposium, Bernanke described high unemployment as a “grave concern” and signaled a readiness to take another round of quantitative easing, which was announced the following month and came to be known as QE3.

—During his appearance in 2014, ECB President Mario Draghi gave a very strong signal of embarking on quantitative easing soon. The following March, QE in the euro area started.

—As then-chairman Greenspan's retirement loomed, the theme for the 2005 symposium was “The Greenspan Era: Lessons for the Future,” focusing on what could be learned from Greenspan's central banking tenure, the longest ever. Raghuram Rajan, then Chief Economist and Director of Research at the International Monetary Fund, and later the 23rd Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, warned about the growing risks in the financial system, which seemed to directly counter what Greenspan had believed. At a celebration honoring Greenspan, symposium participants didn't expect to hear this. Lawrence Summers, former US Treasury Secretary, then-president of Harvard University, called the warnings “largely misguided” and Rajan himself a “luddite” (See Paul Krugman. “How Did Economists Get It So Wrong?” The New York Times, September 2, 2009). However, following the 2007-2008 financial crisis, Rajan's ideas came to be widely seen as prescient. In April 2019, Rajan came to Harvard University as a guest speaker. When moderator Harvard University professor Dani Rodrik referred to the encounter at the 2005 symposium as a debate, Rajan smiled: “it was not really a debate, Summers was just making his points, while I was giving my speech.”

The Jackson Hole Consensus

“Jackson Hole consensus,” a term coined by late Harvard University professor and President Emeritus of the National Bureau of Economic Research Martin Feldstein at 2005 Jackson Hole Symposium, has dominated central banking for decades. Feldstein had attended the symposium many times and contributed much to the program. Kansas City Fed president Esther George highly praised his contributions to this longest-standing central banking event. In a tribute she said: “Marty and Kate Feldstein attended many symposiums here, and Marty was on the program some 18 times. His influential contributions to the economics profession and to public service will long be remembered. He was a wonderful mentor and we are grateful for his advice and input over the years as we considered topics and speakers for this program.”

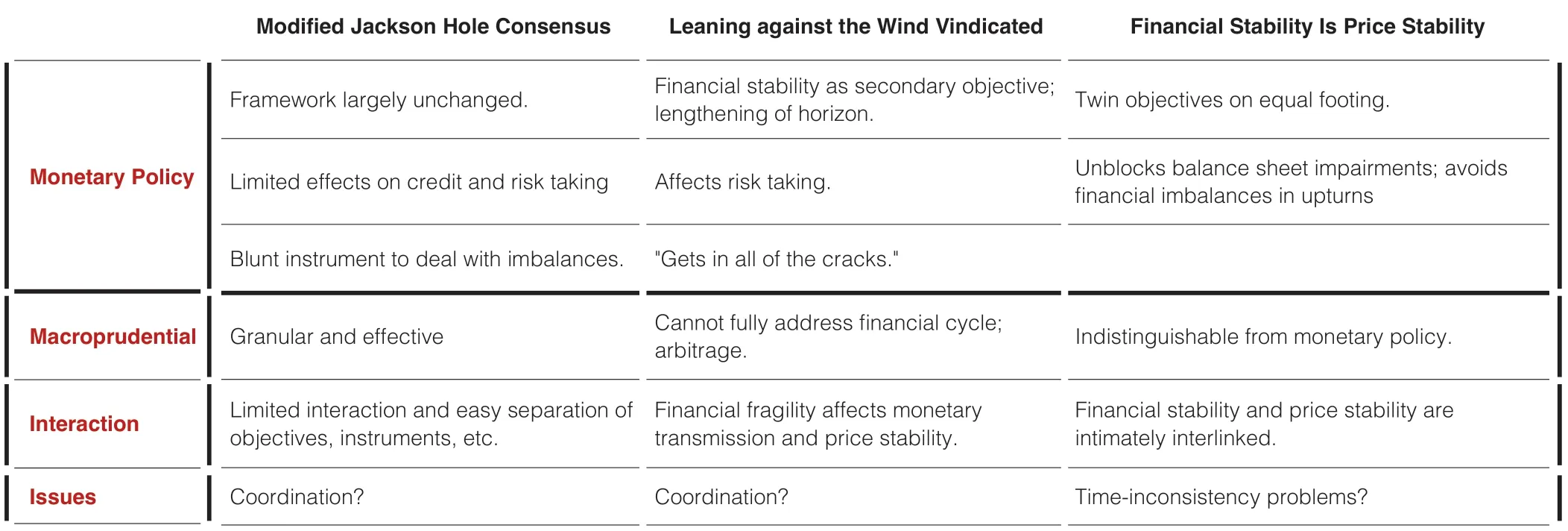

Chart 1: Groups of Participants

The Jackson Hole Consensus holds that monetary policy is the best means to achieve economic stabilization. When insulated from politics, central bankers are at their best. The prime goal of central banks is to keep inflation low and stable. Markets work. Financial crises are history in advanced economies, because skilled central bankers know how to prevent them (See Irwin, N. (2013). The Alchemists: Three central bankers and a world on fire. New York: The Penguin Press) It favors a single inflation target to anchor expectations, and puts a lot of weight on the transparency and predictability of monetary policy. Since 2012, the Fed has adopted an explicit inflation target of 2%. Generally speaking, central bankers seldom focused much attention on their responsibility for broader financial stability, though there were some views, mainly from Europe and Japan, that monetary policy should “lean against” financial risks (See Chart 2).

But in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, “The main tenet of the Jackson Hole consensus—that central banks earn their credibility by having a simple target which the public understands and to which they are held accountable—will be much harder to maintain” (The Economist. Jackson's Holes. August 27, 2009). Previously, especially in the Greenspan era, the Fed ignored financial stability, focusing almost solely on price stability. And after the crisis, the Fed has tried to make a balance between price stability and financial stability. But it also depends more on the preference of the Fed chief; former chair Janet Yellen, for example, was very enthusiastic about financial regulation, but Powell is quite the opposite. There are still national preferences; in the US, there have been few macroprudential measures taken, though many have been introduced in the UK.

Fed officials are concerned more about financial stability these days. Eric Rosengren of the Boston Fed and Esther George of the Kansas Fed dissented from the Fed decision to cut rates on July 31, airing their worries about financial risks. As George put it, easing policy is not a free choice. It pulls forward demand, can make leverage more attractive and creates more risk.

Assessing the Fed's Policy Moves

Last year, the Fed raised rates four times because the unemployment rate was falling, and inflation ran close to the Fed's symmetric 2% objective. But after inflation unexpectedly softened and market volatility soared at the end of 2018, the Fed shelved plans to keep raising rates later on.

Chart 2: Three Views of the Role of Monetary Policy in Achieving Financial Stability

At the FOMC meeting that concluded on May 1 this year, the Fed maintained the federal funds rate in a target range of 2.25 to 2.5% and set the interest rate paid on required and excess reserve balances at 2.35%. On the day the Fed decided to hold rates steady, US stocks fell, bond yields rose and the dollar strengthened. That suggested the markets thought the Fed was more tolerant of weak inflation and was not ready to cut rates.

Foreshadowing a Rate Cut

The Fed's two-day monetary policy meeting ended June 19 with the decision to keep the target fed funds rate unchanged at a range of 2.25 to 2.5%. But there are significant changes in the statement on expectations for the future. The Fed will “take necessary action to maintain economic expansion due to increased uncertainty” depending on future data. The word “patience” disappeared from the previous statement, foreshadowing a rate cut.

When the dust settles, it is still necessary to calm down and carefully collect available data. First of all, it is crucial to figure out reasons for the change in the announcement - the added uncertainty, or “crosscurrents” as Powell stated at the post-meeting press conference. This is the basis for an in-depth understanding of the decision and for tracking and judging the next step.

The announcement of the resolution was made at 2 p.m. and a press conference followed exactly half an hour later, in keeping with tradition. At the press conference, Powell made five points about uncertainty. First, global economic growth was disappointing. Second, trade friction has increased. Third, business confidence has declined and may be further reflected in future data. Fourth, the financial market risk preference has diminished. Fifth, inflation remained weak. All of this could have an impact on the economic outlook.

The Fed is paying more and more attention to uncertainty in monetary policy decisions, which is in line with the speech of Powell's monetary policy seminar held in Chicago on June 4. He pointed out that everyone generally pays more attention to monetary policy operations under normal circumstances, but it is more important to know how to deal with sudden changes in the economic and financial environment.

Despite the increased uncertainty, the Fed's benchmark judgment on the current US economic situation was still positive. Consumption was weak in the first quarter but stabilized after rebounding in the second quarter. Inflation was subdued in the first quarter and picked up slightly in the second. Corporate revenue growth slowed in the second quarter, affecting business investment.

Despite weakness in manufacturing, investment and trade, the services sector was strong, and this had a fundamental impact on the job market.

Powell still believes that weak inflation is temporary and expects it to creep back toward the 2% target as the job market tightens and wages rise. But the recovery will come more slowly than predicted at the last meeting. Wages are rising, but the magnitude is not enough to provide sufficient momentum for price recovery. And all indications show that inflation expectations are still falling. It should be noted that financial markets are far more pessimistic than the Fed when it comes to inflation. Time will tell who is right and who is wrong. At present, the Fed is quietly moving closer to the market.

In his opening remarks at the June press conference, Powell also mentioned the specific discussion of the interest rate cut by members of the FOMC. He pointed out that many members believe that interest rate cuts would be appropriate. The dot plot pointed to interest rate cuts for the first time. Of course, Powell also stressed that the dot plot is only a personal judgment and does not represent the Fed's official forecast.

As to a reporter's question about why there was no interest rate cut at that time, Powell replied that the current evidence was insufficient to support a cut. More time was needed to observe the economy. In response to the strong expectations of cuts in market interest rates, he stressed that the Fed cannot make decisions based on a certain set of data or market sentiment, because individual data and sentiment are highly volatile. Decisions based on these factors may increase uncertainties.

For this meeting, 10 members of the Fed's Open Market Committee voted, 9 in agreement on holding rates steady and 1 opposed. The opponent was James Bullard, the president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, who proposed cutting the Fed funds rate by 25 basis points.

First Rate Cut in a Decade

Finally, after a long wind-up, the Fed acted at the FOMC meeting which ended on July 31. It cut interest rates for the first time in a decade, lowering the federal funds target by 25 basis points and ending the shrinking of its balance sheet ahead of schedule.

From the author's observation, it is hard to say this was the best time to cut interest rates. The economic data released shortly before the meeting were better than expected. Consumption was strong and inflation also showed a rebound. In the statement, the Fed acknowledged that the economy was doing well, but noted concerns about a global economic downturn, rising uncertainties such as trade friction and weak inflation.

Powell told the press conference that the interest rate cut was preventive in nature and effectively an insurance policy. Historically, such “preventive interest rate cuts” have been rare when the economy is doing well. Not long ago, the Fed also maintained that weak inflation was only temporary.

Before the decision, some argued for a 50-basis point cut. The proponents of a more aggressive move were ultimately disappointed. Powell also poured cold water on the market hopes for future interest rate cuts.

It was a cautious cut in interest rates, but also a conflicted one that conveyed a complex message. Bloomberg called it a “hawkish rate cut” while Powell described it as a “mid-cycle adjustment.” I prefer to use “delicate” and “conflicted” to describe it. The stock market fell, the dollar rose, gold rose and then fell, and the yield on short-term Treasury bonds rose instead of falling. This was truly a sign of a conflicted action.

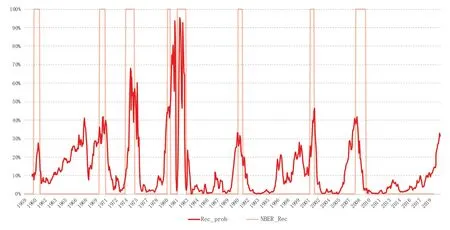

Chart 3: Probability of a US Recession

The Fed's July rate cut had its detractors. While officials targeted this move as a protection against rising risks in an otherwise healthy economy, two voting members of the rate-setting FOMC, Eric Rosengren of the Boston Fed and Esther George of the Kansas Fed, opposed the action. Ahead of the meeting, a number of other officials, including Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker and Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan, had voiced their resistance over the need to cut rates, suggesting a sharp debate might unfold at the next FOMC meeting on September 17-18.

Signs of Recession

Two weeks after the Fed's July rate cut, yields on the US 2- and 10-year debt were inverted—that is, 10-year Treasury yields were less than those of two-year debt. This was the first time since 2007. This is an important leading indicator of a recession. A forecast by the New York Fed shows that the probability of the US economy falling into recession is more than 20% by the end of this year, and more than 30% by June 2020 (See Chart 3).

Not long ago, the US three-month and 10-year Treasury yield were inverted, though the 2- and 10-year spread is clearly more important. History shows that the inversion of the bond yield curve is an important leading indicator that the economy may fall into recession, and the accuracy of the forecast is quite high. The New York Fed's assessment of the prospects for recession stemmed from a forecast map dating from 1959 to July 2020. The 30-year US Treasury yield also hit a new low of 2.01%. Meanwhile, the UK's 2- and 10-year government bond yields also appeared to be inverted.

Due to concerns about the risk of recession, US stocks tumbled 800 points on Aug. 14 and over 600 points on Aug. 23. Oil prices slid and gold rose. In a volatile and uncertain market, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed 370 points higher after the US delayed imposing tariffs on Chinese goods and removed some from its list. The market index also tacked on 270 points as President Trump, speaking at the G7 meeting in Biarritz, France, sounded more optimistic about reaching a trade deal. The contrast between these daily performances shows the fragility of the economy and financial markets.

But why did we see an inversion of the yield curve? In my opinion, there are probably three main reasons.

Direct triggers explain the timing. First of all, the market reassessed Trump's latest pronouncement on tariffs, believing that once again action would be delayed. It did not signal a real settlement of the trade dispute. Second, several new data sets were released just before the US stock market opened; Germany's economy contracted 0.1% in the second quarter on a quarter-on-quarter basis. The last contraction was in the third quarter of 2018. China's industrial added-value output rose 4.8% yearon-year in July, below expectations of a 5.8% gain and an actual 6.3% rise in June. Total retail sales of China's consumer goods rose by 7.6% year on year in July, compared with expectations for 8.4% and the previous month rise of 9.8%. Weak data from two key economies has made already nervous investors even more anxious. Third, the UK also reported a contraction in the second quarter the week before. The last time the UK economy contracted was in the fourth quarter of 2012.

Secondly, rising trade frictions, geopolitical risks and the increased probability of a global recession have caused international capital to seek safe havens in so-called safe assets, including the UK and US Treasury bonds. It has led to lower yields on government bonds, especially longterm ones. This has been another trigger for the inverted yield curve.

Thirdly, global monetary policy has entered an easier cycle. This is the big picture in the background of the Fed's move to cut interest rates for the first time in a decade. In September, the ECB is also likely to cut interest rates and push ahead with its negative interest rate policy. At present, the neutral interest rate of developed economies is low. It had been 2-2.5%, but now it is 0-1.5%, and this limits room for monetary policy action. As the US cuts interest rates, it will get closer to the zero lower bound. At present, there are around US$16 trillion in negative interest rate bonds in the global market. Inevitably, this will have spillover effects on the United States, including arbitrage, thus driving down US bond yields. Former Fed chairman Greenspan said in an interview with Bloomberg recently that he would not be surprised if the US Treasury yields fell below zero, and did not think it was a big deal. He added that zero has no special meaning.

And finally, has there been an overreaction to an inversion in the US yield curve There's no easy answer to this question. It will be up to the Fed and the markets to figure that out. The Jackson Hole Symposium couldn't avoid this crucial issue, and the Fed needs to find a way to anchor expectations.

Seven Messages from Jackson Hole

With global recession fears growing and bond yields tumbling, the 2019 gathering was one of the most anticipated in years. Before the symposium, there was much speculation about what Powell would say in his opening remarks. Harvard professor Larry Summers said it was “dangerous” for central bankers to suggest they had control over assuring sufficient demand and hoped this issue would be discussed at the symposium. Mohamed El-Erian, the chief economic adviser at Allianz SE, said he expected that Powell would start by walking back the July 31 reference to a “mid-cycle adjustment,” instead opening the door for an interest-rate-reduction cycle. That would provide an opportunity to reset expectations in large or small ways. In the end, the symposium ended up sending seven important messages, though with Summers' issue not fully discussed.

01

Economy is in Good Shape, No Recession Worries

It is obvious that one of Powell's goals was to calm the markets and guide market players to a cool-headed assessment of the US economy. That is necessary because the July rate cut was seen by some as a signal that a recession is ahead, not as insurance to keep the economy expanding, as the Fed has tried to portray it. Understanding this is crucial to market expectations. The Fed cares deeply about this, and that's why at the start of his speech, Powell not only described the economy as “in a favorable place,” but also stated that unemployment alone “does not fully capture the benefits of this historically strong job market.” He emphasized rising labor force participation, increasing wages, and worker-training efforts by employers. Powell concluded that after a decade of progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the economy is close to both goals. So, the first message he wanted to send was that there is no worry about a recession at all, at least for now.

02

Inflation Moves Back as ObjectiveInflation fell below the Fed's objective at the start of this year. Now, Powell has announced that it appears to be moving back up closer to the symmetric 2% objective, though there are concerns about a more prolonged shortfall. From a price stability perspective, this seems to have justified the Fed's decision at the June meeting to keep rates steady, but not July's rate cut.

03

Sustaining Expansion through Risk Management

As Powell pointed out, the challenge to the Fed now is to “sustain the expansion” and determine how to “best support maximum employment and price stability in a world with a low neutral interest rate.” Because of the uncertain lags of a year or more of the effects of monetary policy, the Fed “must attempt to look through what may be passing developments and focus on things that seem likely to affect the outlook over time or that pose a material risk of doing so...It will at times be appropriate for us to tilt policy one way or the other because of prominent risks.” And as the year has progressed, the Fed has been monitoring three factors that are weighing on the economic outlook: slowing global growth, trade policy uncertainty, and muted inflation.

04

Trade, Not Rates, Undermine the US Economy

“Trade policy uncertainty seems to be playing a role in the global slowdown and in weak manufacturing and capital spending in the United States,” Powell said. He also conceded that fitting trade policy uncertainty into current monetary policy framework is “a new challenge.”

Setting trade policy is the business of Congress and the Administration, not that of the Fed, but uncertainty about trade policy could “affect the appropriate stance of monetary policy,“ though there are “no recent precedents to guide any policy response to the current situation,” according to Powell. The current monetary policy framework “cannot provide a settled rulebook for international trade.” What the Fed can do is to try to “look through what may be passing events, focus on how trade developments are affecting the outlook, and adjust policy to promote our objectives” (See Chart 4).

05

Warnings of ‘Significant Risks' Harden Bets for Rate-Cut

Powell said the US economy is in “a favorable place” but faces “significant risks,” reinforcing bets for another rate cut in September. He appeared to be satisfied with the impact of July's rate cut, emphasizing that the shifts in the anticipated path of policy have eased financial conditions and help explain why the outlook for inflation and employment remains largely favorable.

Powell defined the three weeks since the July FOMC meeting as being “eventful,” beginning with the announcement by President Trump of new tariffs on imports from China. He said that the Fed has seen further evidence of a global slowdown, notably in Germany and China. Geopolitical events have been much in the news too, including “the growing possibility of a hard Brexit, rising tensions in Hong Kong, and the dissolution of the Italian government.”

06

Strong Dissents among Fed Officials

Some Fed officials opposed the July's rate cut, and several others seemed cautious about a further one in September. They dismiss the notion that the US economy is headed towards a recession, and are not convinced that slowing trade and global growth will significantly dent US economy. Some argue that lower rates could create financial risks.

07

Powell's Trade Policy Concerns Are Being Proved Correct

Any reassurance people got from Chairman Powell in Jackson Hole on July 23 was undone within minutes. Powell had barely finished his remarks when President Trump unleashed a Twitter tirade against him and also escalated another round of trade war with China.To sum up: the above seven messages suggest that though the US economy is in a favorable place, as Powell had put it, there are significant risks and uncertainties. There is very high probability that the Fed will cut rates another time in September. Dissents remain among Fed officials, however, and it's important to watch how they play out months from now.

Chart 4: Trade War Impacts and Monetary Policy

Central Banks' Independence

Has long been portrayed by economists as a bulwark against high inflation, central banks' independence has always been a topic at Jackson Hole. The current low-inflation, lowrate situation obviously makes this an even hotter issue.

As former Fed chair Bernanke stated, the Fed has fewer institutional protections than most other advanced economy central banks. The protections of the Fed's independence are not explicitly guarded by statute or treaty, as is the case for the Bank of Japan, the Bank of England, and the European Central Bank, except indirectly and implicitly (Ben S. Bernanke. 2019. Monetary Policy in a New Era. A book chapter in Evolution or Revolution? Rethinking macroeconomic policy after the Great Recession. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press).

The Fed's independence is seriously threatened now. President Trump's unyielding criticism of the central bank really depressed Powell, who has been trying hard to avoid worsening the friction. Last year, Trump lashed out at Powell for hiking rates and tightening the balance sheet, and now, for not cutting rates fast enough or more aggressively. He even referred to Powell as an “enemy.” Speaking in an interview on the Fox Business Network, Janet Yellen said of the president: “He's made clear in various interviews and tweets that he doesn't believe that the Fed should be independent.”

On August 27, only days after the Jackson Hole Symposium, former New York Fed president William Dudley wrote an article urging the Fed to block Trump by not cutting rates, thereby preventing the president from escalating the trade war and even being re-elected. Dudley's article drew considerable criticism, and Fed officials quickly dismissed his recommendations. “Political considerations play absolutely no role,” a Fed spokeswoman said. The Fed knows clearly that the best way to maintain independence is to avoid political considerations when implementing policy.

To protect its independence, the Fed has to explain what it is doing and why. And most importantly, in this complex world, under huge pressure from all sides, the Fed has to get things right.

Dealing with Monetary Policy Divergence

Ten years after the financial crisis, central banks have charted different policy courses, with some approaching a neutral policy setting, while others have yet to start the process of removing accommodation. This monetary policy divergence issue might become the theme of some future Jackson Hole Symposium, because the danger of spillover effects from one central bank to another can't be ignored.

Back in March, the ECB became the first developed economy central bank to loosen monetary policy. It provided banks with new targeted longer term refinancing operations after a three-year hiatus, when it announced that the low interest rates would be maintained for a longer length of time. Three months later, at the ECB's annual research meeting in Sintra, Portugal - a meeting somewhat akin to the Fed's famous Jackson Hole Symposium, Draghi made it clear that window guidance, rate cuts (though already negative) and further quantitative easing are all available tools.

Interestingly, Draghi's speech prompted strong dissatisfaction from President Trump, who insisted the ECB intends to devalue the euro and gain an unfair advantage against US. This direct criticism of a foreign central bank is quite unusual. Draghi replied that the ECB's policy goal is not to affect the exchange rate.

As it happened, Draghi's remarks came on the same day that the Fed started its two-day monetary policy meeting, which ended with a signal that a rate cut might emerge when conditions are met, thus changing the previous tone. But the market expects the Fed to cut interest rates twice this year. Trump's pressure on Powell seems to have increased. In this context, it is hard to say whether the loose signal that Draghi delivered has increased or eased the Fed's burden.

After the ECB released a fresh signal of easier policies on June 18 and the Fed set the stage for a rate cut on June 19, the BOE announced at its June 20 policy meeting that it would raise interest rates if Brexit goes smoothly. The BOE's signal received considerable attention. But at this Jackson Hole Symposium, BOE governor Mark Carney said a no-deal Brexit would probably lead to easing. This could be seen as a subtle change of tone in the BOE's monetary stance, given that hard Brexit risks are rising.

- China Forex的其它文章

- Encouraged Areas for Foreign Investment

- Anti Money Laundering Efforts in Trade Finance

- China's Foreign Exchange Policies

- New Policy on Managing Cross-border Funds in Local and Foreign Currencies

- Will Libra Usher in an Era of Digital Currencies?

- Foreign Investment Steady Despite Sino-US Trade Row