Effectiveness of health coaching on diabetic patients: A systematic review and metaanalysis

Nashwa Mohamed Radwan ,Hisham Al Khashan,Fahad Alamri,Ahmed Tofek El Olemy

1Department of Public Health and Community Medicine,Tanta University,Tanta,Egypt.2Consultant in Clinical Education Department,Ministry of Health,Riyadh,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.3Family Medicine Consultant,Ministry of Health,Riyadh,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.4National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine,Ministry of Health,Riyadh,Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Abstract

Keywords: Health coaching,Type 2 diabetes mellitus,Randomized controlled trials,Hemoglobin A1c,Weight,High-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Background

Chronic diseases represent a growing public health problem around the world.Approximately half the adults in the United States have at least 1 chronic disease,and 26% have multiple chronic diseases [1].Diabetes mellitus is an emerging global epidemic disease,and more than 346 million people suffer from type 2 diabetes mellitus in the world [2].By the year 2030,diabetes mellitus is predicted to become the seventh leading cause of death in the world [3].The prevalence of diabetes mellitus has been increasing.Seven million people are diagnosed with this disease each year and every 10 seconds,a person dies because of diabetes mellitus-related causes [4].Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease which needs the lifelong medical and nursing intervention and lifestyle adjustment [5].The Diabetes Mellitus Control and Complications Trial (1998) showed that for every 1% reduction in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c)levels,there was a 40-50% reduction in risk for microvascular and neuropathic complications [6,7].However,patient’s non-compliance with treatment often exceeds 50% and have even been reported as high as 93% [8,9],emphasizing the clear need for interventions focused on the lasting behavior change and accountability.To change patients’ health behaviors,education-based initiatives needs patient’s self-management support and cooperation [10,11].Tools that provide information about options and consequences may increase patient’s knowledge and improve their attitudes to self-care,but the impact on behavior change is little [12].Approaches of improving self-efficacy increase the possibility of behavior change and contribute to better health outcomes and more appropriate healthcare utilization[11].

The first use of the term “coach” arose around 1830 in Oxford University as a slang in relation with an instructor or trainer or tutor who “carried” a student through an exam.The term coaching thus refers to the process of transporting people from where they are to where they want to be.In 1915,the National Board of Medical Examiners was founded.In 2002,Wellcoaches partnered with the American College of Sports Medicine.In 2010,the National Consortium for Credentialing Health and Wellness Coaches was founded.In 2017,the International Consortium for Health and Wellness Coaching was established [13].Coaching as a method to improve healthy lifestyle behaviors has received special attention in recent years [14].A healthy lifestyle is important in patients care and help to prevent many lifestyle diseases that are dramatically increasing during recent years [15,16].Health coaching has become as a widely adopted intervention to help individuals with chronic conditions adopt health-supportive behaviors that improve both the health outcomes and quality of life [17].A comprehensive conceptual definition of health coaching was provided by Woleveret al.(2013).The authors defined coaching as “a patient-centered approach wherein patients at least partially determine their goals,use self-discovery or active learning processes together with content education to work toward their goals,and self-monitor behaviors to increase accountability,all within the context of an interpersonal relationship with a coach” [18].The few published randomized controlled trials (RCT) on the use of health coaching for patients with diabetes mellitus have reported mixed results.There is a need for evidence synthesis to evaluate the effectiveness of health coaching,particularly to examine the components that are necessary for its effectiveness and settings in which it is most applicable.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the effectiveness of health coaching on modifying health status and lifestyle among diabetic patients and to clarify the characteristics of coaching delivery that makes it most effective.

Materials and methods

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies.We included RCT on health coaching interventions reported in articles that were published in English during the past 15 years (from January 2005 through December 2018).

Types of participants.Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with no mental or physical limitations that would preclude participation were included in the study.

Types of interventions.Details of the interventions provided in the article descriptions of the characteristics of the included studies were as follows: The interventions were primarily health coaching interventions that focused on diabetes mellitus education,diabetes mellitus self-management skills,providing social and emotional support,providing assistance for lifestyle modification (advice on diet,physical activity,weight control,and tobacco cessation),and facilitating medication adherence.The comparator used was usual diabetes mellitus care.All services available to patients in normal situation care are included in the usual care,including access to a nutritionist and diabetes mellitus educator through referral from a primary care clinician.

Types of outcome measures.Primary outcomes included hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and cardiovascular disease risk factors,including systolic blood pressure (SBP),diastolic blood pressure (DBP),triglyceride,high-density lipoprotein cholesterol(HDL-C),low-density lipoprotein cholesterol(LDL-C),total cholesterol,and body weight.Secondary outcomes included quality of life,self-efficacy,self-care skills and psychological outcome.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded non-RCT,patients with mental or physical limitations,patients with HbA1c < 7%,SBP< 140 mmHg,cholesterol level < 100 mg/dL,and non-English material.

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified studies through systematic searches of the Cochrane,Medline,PubMed,Trip,and Embase databases.We adapted the preliminary search strategy for Medline (Ovid) for use in the other databases.The search was conducted using the following terms: diabetes,OR diabetes mellitus,OR type 2 diabetes AND diabetic coaching,OR health coaching for diabetes,OR telephone coaching,OR behavior support intervention,OR health coaching intervention,OR diabetic patient engagement,OR patient engagement and coaching,OR peer coaching,OR nurse health coaching,OR medical assistant for diabetes AND RCT.We checked the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies.The titles and abstracts of potential articles were read independently by (NMR and ATE).An article was rejected only if both review authors determined from the title or abstract that the article was not a randomized controlled trial.After reviewing the full articles,the studies that were not relevant to the review were excluded.Remaining records were independently checked by the same review authors.All papers that were thought to be of relevance were obtained and read by (NMR and ATE)independently.

Data extraction and management.We used a data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data.One author (NMR) extracted the study characteristics from the included studies.We extracted the following characteristics(Supplementary annex 1): Methods: study design,total duration of study,and study setting; Participants:number,mean age,diagnostic criteria,and inclusion and exclusion criteria; Interventions: intervention and comparison,including method,duration,frequency of coaching,and coaching qualification; Outcomes:primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected; Risk of bias: 2 authors (NMR and ATE)independently extracted outcome data from the included studies.Any disagreements were resolved by discussion.One author (NMR) transferred the data into the Review Manager (RevMan) 5.3 software [19].

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies.Two authors (NMR and ATE) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [20].We resolved any disagreements by discussion.We graded each potential source of bias as high,low,or unclear,and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the risk of bias table.We assessed risk of bias according to the following domains:random sequence generation (selection bias),allocation concealment (selection bias),blinding of outcome assessment (performance bias),incomplete outcome data (attrition bias),and selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

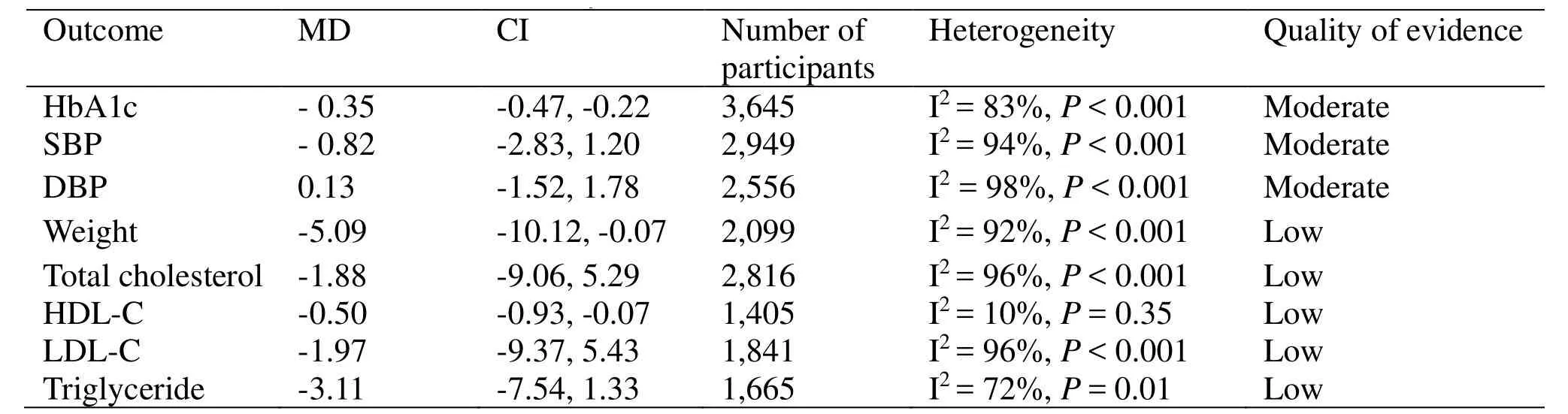

Assessment of quality of evidence.We assessed the quality of evidence of the primary outcomes using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment,Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach[21].The results are presented in Table1.The GRADE system considers quality to be a judgement of the extent to which we can be confident that the estimates of effect are correct.The level of “quality”is judged on a 4-point scale: High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; Very low quality: any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

We initially graded the evidence from RCT as high,and downgraded them later by either 1 or 2 levels after full consideration of the 4 recommended domains affecting study limitation: risk of bias in the included studies,directness of the evidence,consistency across studies,and precision of the pooled estimate or the individual study estimates.

Measures of treatment effect.We used RevMan 5.3 to manage the data and to conduct the analyses [19].We calculated mean difference (MD) with 95%confidence interval (CI) when the studies use the same scale.

Dealing with missing data.We contacted investigators to obtain missing numerical outcome data where possible.

Dealing with heterogeneity.We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the studies in each analysis [22].

Significant difference analysisWe summarized and analyzed all eligible studies in RevMan 5.3.Two authors (NMR and ATE) extracted the data; the first author entered all the data and the second author checked all the entries.Disagreements were resolved by discussion.We undertook meta-analyses onlywhere this was meaningful.We combined the data using a random effects model.

Table1 Summary of the main outcomes of the included studies

Results

Search results

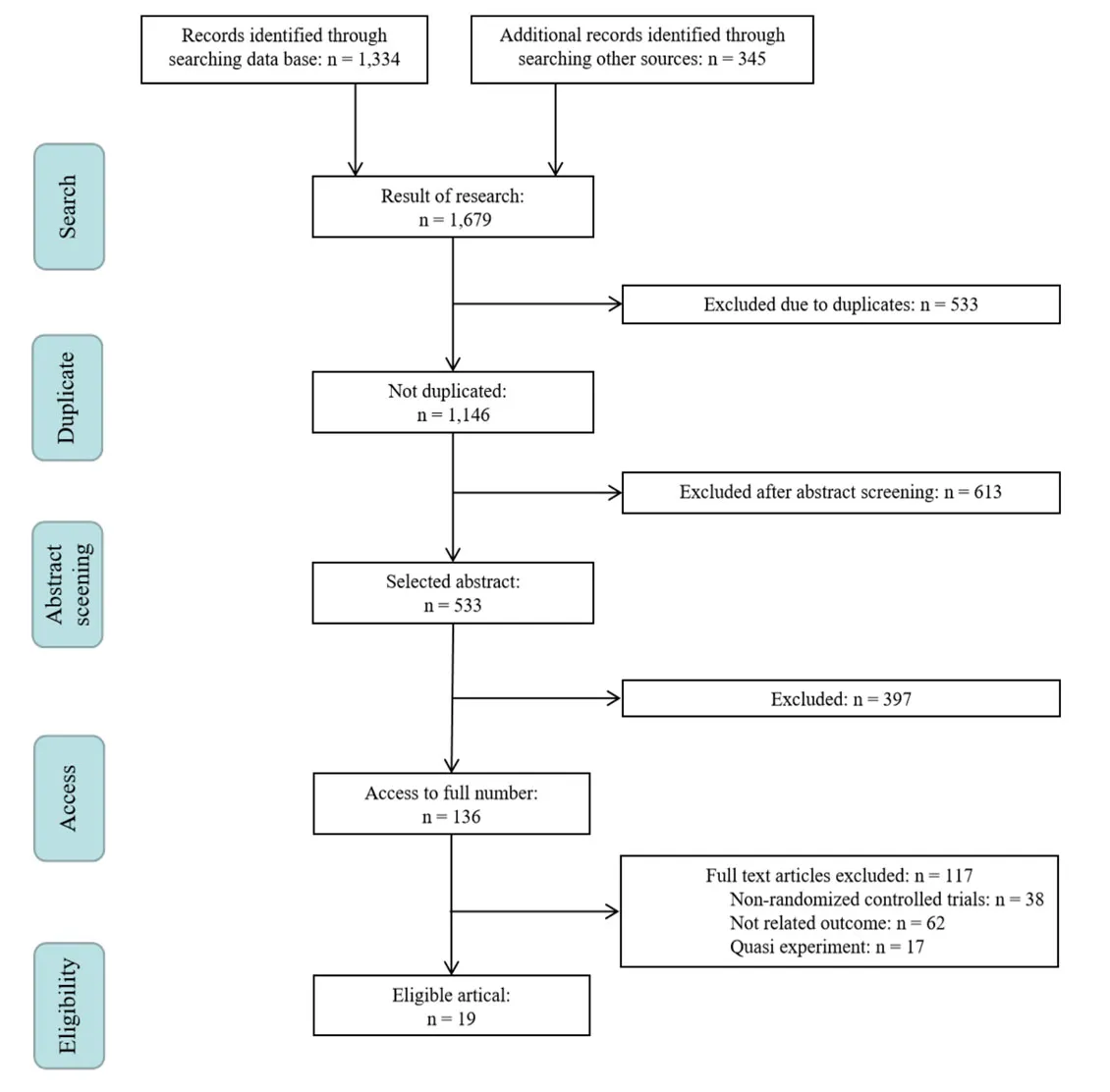

Our search found 1,679 potential articles.A total of 533 remained after removal of duplicates.Abstracts were reviewed based on inclusion and exclusion criteria by 2 authors (NMR and ATE) independently.One hundred and thirty-six full-text articles were independently assessed for eligibility.Of these,19 met the inclusion criteria.Details of the flow of studies through the review are presented in the paper flow chart (Figure1).

Included studies

Details of the methods,participants,interventions,comparison groups,and outcome measures for each of the included studies in the review are provided in a table depicting the characteristics of included studies (Table1 in the supplementary material).

Study participants

The participants of this review (3,573) were diabetic patients (type 2) aged 18 and over (in all the studies),with no mental or physical limitations that would preclude participation in the study.The inclusion criteria were as follows: HbA1c > 7.5% [23-30]; at high risk for diabetic complications e.g.,cardiovascular risk factors: body mass index > 27 kg/m2 [23,30],SBP > 140 mm Hg [28],LDL-C level > 100 mg/dL [30].

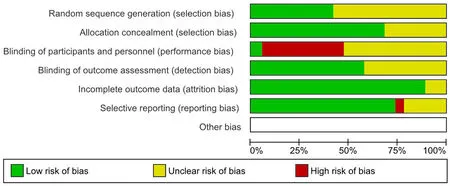

Risk of bias in included studies

We present details of risk of bias for each of the included studies in the risk of bias table (Figure2).Overall,the studies included in this review were at some risk of bias,except the study of Kempfet al.[23].All studies had at least 1 domain with unclear risk of bias,except the study of Kempfet al.[23],and 2 studies were unclear for attrition bias [29,31].One study was at high risk for reporting bias [32].

Random sequence generation (selection bias).The random sequence generation was adequate in 8 studies [23,25,30-35] and unclear in 10 studies [24,26-29,36-40].

Allocation concealment (selection bias).Allocation concealment was unclear in 6 studies [24-25,35,38,39,41] and adequate in the remaining 13 studies.

Blinding (performance bias).Three studies masked outcome assessors to the treatment allocation (low risk) [23,29,32],and 5 studies did not (high risk)[28,35-36,38,41].The risk was unclear in 11 studies [24-27,30-31,33-34,37,39,40].

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).Attrition bias was unclear in 2 studies [29,31] and low in the remaining 17 studies [23-28,30,32-35,36-41].

Selective reporting (reporting bias).There was low risk of selective reporting bias in 15 studies [23-29,30,31,33,35,38-41],unclear risk in 3 studies [29,36-37],and high risk in 1 study [32].

Other potential source of bias.There was insufficient information to judge whether there were other risks of bias.

Characteristics of health coaching interventions

Figure1 The paper flow chart

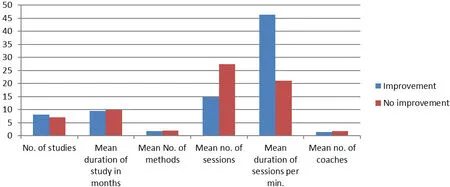

With regard to the characteristics of the health coaching interventions among the included studies,it was observed that there were differences in the strategy of health coaching delivery,including number of participants,method,duration and frequency of coaching,and coaching qualification.All these factors affected the outcome in the intervention groups.Number of participants in the intervention groups ranged from 21 [34] to 385 [33].Most of the coaching sessions (in 14 studies) were conducted through telephone calls,either alone or with other coaching methods.Other studies used either educational classes,discussion,in-person visits,person contact,video,or electronic action plan with different levels of outcome.Duration of health coaching varied: 3 months in 1 study,6 months in 8 studies,9 months in 3 studies,12 months in 4 studies,13 months in 1 study,15 months in 1 study,and 18 months in 1 study.Frequency of sessions included 2 separate days,weekly,biweekly,monthly,every 6 weeks,every 2.5 months,and every 3 months.Also,qualifications differed among the studies.The coaches were nurses in 8 studies; specialists in 3 studies; social workers or psychologists in 4 studies;dietitians,trained medical assistants,or community health workers in 2 studies; and trained diabetes coaches,peer coaches,behavior counselling specialists,health coaches or professional caregivers in 1 study.The considerable variation in the characteristics of health coaching indicates that there is no standardization in health coaching with regard to number of participants,method,duration,or frequency of coaching in addition to coaching qualification,and hence variations in outcome.However,it was observed that the most effective delivery strategy for health coaching was few coaching sessions with increased duration of each session (Figure3).

Primary outcomes

HbA1c.

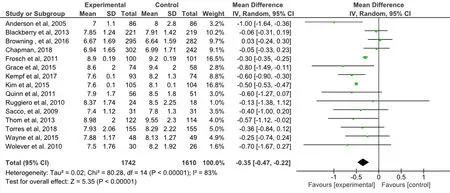

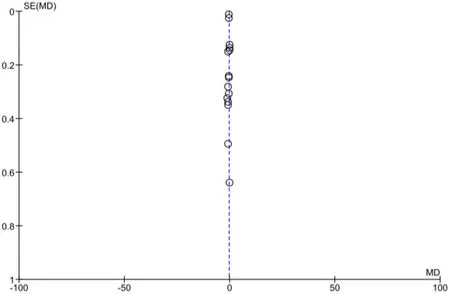

HbA1c was assessed in 15 studies with 3,645 participants (Figure4).A statistically significant reduction in the mean HbA1c is reported among intervention groups after health coaching interventions compared with the control groups (MD= -0.35,CI = -0.47,-0.22).A statistically signif i cant high heterogeneity between studies is observed (I² =83%,P< 0.01),indicating considerable inconsistency among the included studies in the estimate,which may be due to differences in study participants,strategy,method,duration,or frequency of health coaching and coaching qualification.The test for funnel plot asymmetry is presented in Figure5.

Cardiovascular disease risk factors

SBP.SBP was recorded in 9 studies among 2,949 participants (Figure1 in the supplementary material).The pooled effect shows no statistically significant difference in mean SBP in the intervention groups after the health coaching interventions (MD = -0.82,CI = -2.83,1.20,P= 0.43) with evidence of statistically signif i cant considerable between-study heterogeneity (I² = 94%,P< 0.01).The considerable heterogeneity may be explained by the variations in baseline level of SBP among the included studies along with the variations in management method and coaching strategy.Test for funnel plot asymmetry was not applied because the number of included studies in the meta-analysis was less than 10 [23].

DBP.DBP was assessed among 2,556 participants in 7 studies (Figure2 in the supplementary material).No statistically significant difference is found in the mean DBP after health coaching interventions (MD =0.13,CI = -1.52,1.78,P= 0.88) with considerable heterogeneity between studies (I2= 98%,P< 0.01,which can be attributed to the same reasons as SBP).

Weight.Weight was analyzed among 2,099 participants in 5 studies (Figure3 in the supplementary material).No statistically significant reduction in the mean weight is observed among intervention groups after health coaching interventions (MD = -5.09,CI = -10.12,-0.07,P=0.05).However,the analysis showed considerable imprecision with wide CIs,as the analysis included only 5 studies and considerable heterogeneity (I2=92%,P< 0.01),which could be attributed to variations in the coaching strategy (e.g.,follow-up period).

LDL-C.LDL-C was compared among 1,841 participants in 6 studies (Figure4 in the supplementary material).Clinical improvement is evident with reduction in the mean LDL-C in all included studies after health coaching intervention;however,the pooled effect is not statistically significant with low precision (wide CIs) (MD =-1.97,CI = -9.37,5.43,P= 0.60) and considerable between-study heterogeneity (I2= 96%,P< 0.01).

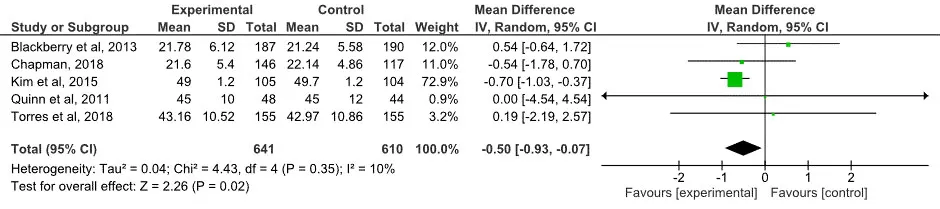

HDL-C.HDL-C was studied among 1,405 participants in 5 studies (Figure6) with statistically significant improvement in the MD of HDL-C after health coaching among studied participants (MD =-0.50,CI = -0.93,-0.07,I2= 10%,P= 0.02).

Triglyceride.The mean triglyceride was evaluated in subgroup analysis among 1,665 participants in 4 studies (Figure5 in the supplementary material).No statistically significant improvement in mean triglyceride is observed among the intervention groups after health coaching interventions with low precision (wide CI) (MD = -3.11,CI = -7.54,1.33,P= 0.17) and moderate heterogeneity between studies(I2= 72%,P= 0.17).

Total cholesterol.The mean total cholesterol was examined in 8 studies among 2,816 participants(Figure6 in the supplementary material).The pooled effect of total cholesterol between intervention and control groups is not statistically significant (MD =-1.88,CI = -9.06,5.29,P= 0.61) and considerable between-study heterogeneity (I2= 96%,P< 0.01).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes included quality of life,self-efficacy,self-care skills,and depressive symptoms.Quality of life was assessed in 6 studies,and significant improvement was found in 3 studies[23,34,41].No significant improvement was found in the other 3 studies (1,471 participants) [32,33,36].Self-efficacy was assessed in 6 studies,and significant improvement was found in 5 (1,220 participants) [26,34,37-38,41],and only the study of Blackberryet al.,with 56 participants found no significant improvement [36].Diabetes self-care was assessed in 3 studies,and significant improvement was found in Raanawongsaet al.among 252 participants [39],whereas the studies of Froshet al.,and Chapmanet al.,found no significant improvement in self-care activities among 882 participants [29,33].Psychological distress and depressive symptoms were assessed in 6 studies with significant improvement in 4 among 934 participants[25-26,31,34,40].While the study of Blackberryet al.,recorded no significant improvement [36].

Quality of evidence

We assessed quality of evidence in this review using the GRADE approach [21],and considered the 4 domains that are recommend for evaluation of study limitation: risk of bias in the included studies,directness of the evidence,consistency across studies,and precision of the pooled estimate or the individual study estimates.The studies included in this review were RCT with considerable risk of bias,as shown in Figure2.Also,directness was not found to be lacking in this review,as all the included studies reported health coaching interventions aimed at improving health outcome and quality of life.Regarding the pooled estimate of HbA1c,SBP,and DBP,we judged the quality of evidence to be moderate,indicating moderate confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect,and further research is likely to change the estimate.We downgraded the evidence by 1 level because of considerable heterogeneity (I2= 83%,94%,and 98%,respectively),indicating very high inconsistency among included studies in the estimate.Concerning the quality of evidence for weight,triglycerides,total cholesterol,HDL-C,and LDL-C,we judged the quality of evidence to be low,indicating low confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect,and further research is very likely to change the estimate.We downgraded the evidence by 2 levels because of considerable heterogeneity and imprecision (small sample size,as few studies were included in the analysis,resulting in wide CIs).We detected statistically significant heterogeneity in most of the meta-analyses,suggesting that the percentage of the variability in effect estimate is due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error(chance).The heterogeneity may be due to differences in study participants,geographical location,strategy,method,duration,or frequency of health coaching and coaching qualification.

Figure2 Risk of bias percentages of included studies

Figure3 Characteristics of the health coaching delivery

Figure4 Forest plot of the mean difference of HbA1c after health coaching

Figure5 Funnel plot of the mean difference for HbA1c

Figure6 Forest plot of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol after coaching intervention

Discussion

This review examined the effectiveness of health coaching interventions on diabetic patients.It included 3,573 participants from 19 RCT published during the past 15 years in different countries.We found that the pooled effect of health coaching interventions was a statistically significant reduction in HbA1c and HDL-C.The most effective delivery strategy for health coaching associated with significant improvement of HbA1c was decreasing the frequency of coaching sessions while increasing the duration of each session.Also,no significant difference was found for SBP,DBP,weight,triglyceride,LDL-C,or total cholesterol.Mix results were found for the effect of health coaching on quality of life,self-efficacy,diabetic self-care,and depressive symptoms.It is important to note that these results should be interpreted with caution because of high heterogeneity due to many factors,including variations among the interventions(methods,duration,frequency of health coaching interventions,and coaching qualification),variations among the participants,and a small number of included studies in the analysis of some measuring outcomes.

In addition,Sherifaliet al.,found that the pooled effect of diabetes health coaching overall was a statistically significant reduction of HbA1c levels by 0.32 (95% CI = -0.50,-0.15) [42].Longer diabetes health coaching exposure (> 6 months) resulted in a 0.57% reduction in HbA1c levels (95% CI = -0.76,-0.38),compared with shorter diabetes health coaching exposure (≤ 6 months) (-0.23%; 95% CI = -0.37,-0.09).There are numerous definitions of health coaching,and there is no standardized strategy of coaching delivery nor is there a clearly defined role of the health coach (e.g.,educator,navigator,facilitator,or partner).Numerous studies have examined health coaching,with mixed results.For example,studies on health coaching for patients with diabetes [43-45],obesity [32,46-47],cancer [48],and cardiovascular disease [49-51] have demonstrated positive effects on health behaviors or health outcomes.However,other studies that have examined health coaching found non-significant benefits for health outcomes [30,52-54].Mixed results on the effect of health coaching on quality of life,self-efficacy,diabetic self-care,and depressive symptoms were reported in the present review.Also,Ekonget al.found that motivational interventions in type 2 diabetic patients showed promising results for dietary behaviors [55]; however,only 4 out of 7 studies had a significant improvement in healthy eating compared with usual care,and the magnitude of the impact was not determined.Only a statistically significant difference was recorded.However,the authors did not report a significant effect on physical activity (6 studies; 1,884 participants),alcohol reduction (2 studies; 1,192 participants),smoking cessation (3 studies; 994 participants),waist circumference (2 studies; 309 participants),or cholesterol levels (5 studies; 2,797 participants).Only 1 study out of 7 demonstrated a significant effect on self-management of diabetes,blood glucose level,weight loss,body mass index,and blood pressure compared with usual care.Similarly,some systematic reviews have suggested that the use of health coaching through telephone can be effective in improving quality of life and health outcomes of older people[56-58].Others have shown inconclusive results[59-60].Also,Veazieet al.examined the evidence,usability,and features of commercially available mobile applications for self-management of type 2 diabetes and found that patients experienced clinical and statistical improvement in HbA1c but no improvements in quality of life,blood pressure,weight,or body mass index outcomes [61].Correspondingly,Cramer JA reported that health coaching though electronic monitoring systems was useful in improving medication adherence of diabetic patients [8].Sapkotaetal.found that interventions addressing non-adherence factors demonstrated mixed results,making it difficult to determine effective coaching intervention strategies to promote quality of life and health outcome [62].

Limitations of this review include low or insuff i cient strength of evidence for most outcomes across the various included studies.These low grades were driven by high or unclear risk of bias within individual studies(mainly due to inability to blind patients in the intervention group to health coaching),and lack of consistency and precision among outcomes included in subgroup analysis with few studies and small number of participants with wide CIs.Also,there was considerable heterogeneity between studies due mainly to differences in study participants,geographical location,method and duration,frequency of health coaching,and coaching qualification.Further,systematic review and meta-analysis with considerable consistency and precision focusing on different methods (e.g.,educational classes,face-to-face,telephone,and video),number of participants (e.g.,single and group therapy),and different coaching qualifications (e.g.,doctor,nurse,social worker,and peer coach) are needed to confirm the effectiveness of health coaching on controlling other diabetic risk factors and to standardize the effective coaching strategy and settings in which it is most applicable.

Conclusion

Health coaching intervention has significant effect on HbA1c and HDL-C.The most effective strategy for coaching delivery found in the current review was decreasing the frequency of coaching sessions while increasing the duration of each session.However,these results should be interpreted with caution,as the evidence comes from studies at some risk of bias with considerable heterogeneity and imprecision.

Traditional Medicine Research2019年6期

Traditional Medicine Research2019年6期

- Traditional Medicine Research的其它文章

- Study on the relationship between the structure of bacterial flora on the tongue and types of tongue coating in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

- A systematical review of traditional Ayurvedic and morden medical perspectives on Ghrita(clarified butter):a boon or bane

- Effects of Siwei Yuganzi decoction on LXRα and CYP7A1 in hyperlipidemic rats

- Treatment of diabetic foot ulcer with medicinal leech therapy and honey curcumin dressing:a case report

- Tu Youyou:A scientist moving forward in controversy

- The research of acupuncture on the treatment of alcohol dependence: hope and challenge