工业酶结构与功能的构效关系

张锟,曲戈,刘卫东,孙周通

工业酶结构与功能的构效关系

张锟*,曲戈*,刘卫东,孙周通

中国科学院天津工业生物技术研究所,天津 300308

工业酶是绿色生物制造的“芯片”,支撑着下游数十倍甚至百倍的产业。解析工业酶结构与功能关系是对其设计改造并应用于工业生产的基础。近年来随着蛋白结构解析技术和计算模拟技术的发展,酶结构与功能的构效关系得到更加深刻的认识,使得酶理性设计,甚至是从头设计成为可能。文中围绕酶结构的可塑性及其催化功能的多样性,综述工业酶结构与功能构效关系的研究进展及应用,并展望该领域的未来发展前景。

工业酶,结构与功能,结构可塑性,生物催化

作为生物催化剂,酶催化具有反应条件温和、专一性高及环境友好等优势。天然酶已形成无数错综复杂的结构,来行使类型多样的催化反应[1]。酶的结构决定其功能,对绝大多数酶来说,其催化功能 (如底物特异性、催化效率) 通常依赖于酶催化口袋中的一小部分氨基酸残基[2],但其他特性如热稳定性等可能涉及远端氨基酸残基[3]。随着越来越多的晶体结构得到解析,以及通过随机突变、(半)理性设计[4]等定向进化技术获得大量的催化特性优化的工业酶[5],人们可以更好地理解酶结构与功能之间的关系。近年来基于晶体结构解析与计算分析,科学家们可以更加深入地了解酶的催化机制及对应的结构特征,为促进其工业应用奠定了基础。基于该领域的最新进展,本文首先着重介绍酶结构的可塑性及相应催化特性的多样性,之后介绍酶结构对催化特性的影响和构效关系研究方法,最后探讨展望该领域的发展前景。

1 酶结构的可塑性

酶能够在温和条件下催化特异化学反应,能否与底物选择性结合是酶执行催化功能的主要决定因素。酶结构的特定空间排列,是形成酶-底物过渡态复合物的前提条件。氨基酸彼此之间通过酰胺键连接在一起形成多肽链骨架,并卷曲折叠成有规则的二级结构,包括α-螺旋、β-折叠、β-转角及无规卷曲等。多个二级结构借助非共价力,如疏水相互作用、氢键、离子键和范德华力,进一步折叠组装形成有功能的三级结构(图1)。由于非共价键相对较弱,三级结构容易受到外界环境的影响(如温度、pH、底物诱导等) 发生构象变化,因此酶结构具有可塑性,进而影响其催化功能和分子特性。

图1 蛋白质结构组装:从左到右分别为一级序列、二级结构和三维结构

1.1 酶骨架可塑性

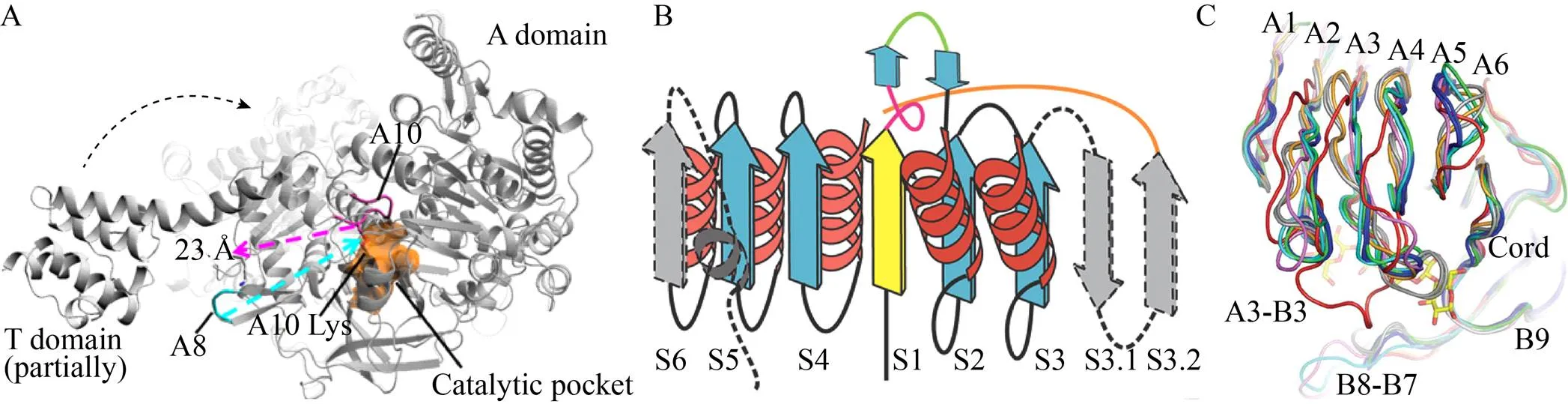

酶骨架的构象不是刚性、静止的,而是柔性、动态的。酶与底物分子相互作用时酶构象有时发生轻微改变,有时则发生剧烈变构,酶骨架的可塑性保障了功能的有效实施。以羧酸还原酶为例,它能催化羧酸到醛的还原反应,来源于赛格尼氏杆菌的羧酸还原酶SrCAR的晶体结构表明,腺苷化结构域和硫酯化结构域存在大尺度的变构效应,以实现利用同一个催化口袋先后催化腺苷化及硫酯化反应[6-7]。曲戈等的进一步研究表明,SrCAR的K629和K528分别在腺苷化和硫酯化阶段扮演着重要角色:在腺苷化阶段,K629位于腺苷化结构域催化口袋中心;而硫酯化阶段发生了变构,K629移出催化口袋,K528取而代之并负责催化硫酯化反应 (图2A)。将这两个位点突变为丙氨酸后,突变体K629A和K528A均丧失了对模式底物的催化能力[8]。此外,结构域或拓扑结构发生大尺度变构在酶催化功能演变中发挥重要作用[9]。例如卤代链烷酸脱卤素酶 (Haloalkanoicaciddehalogenase,HAD) 超家族根据功能不同分为磷酸酯酶、ATP酶、脱卤素酶和糖磷酸酶,其不同成员之间Cap结构域 (Cap domain) 的差异造成了功能和底物的特异性(图2B)[10]。

图2 酶骨架可塑性对其催化功能的影响.(A)SrCAR从腺苷化阶段变构到硫酯化阶段. 虚线箭头表示腺苷结构域(A domain)与硫酯结构域(T domain) 的变构方向,源自文献[8]. (B) 经典HAD结构域示意图:黄色,含有催化残基Asp的链;蓝色,在所有HAD超家族成员中保守的核心链;灰色,在祖先酶结构中可能没有发生的结构元素;绿线,C1 Cap域的插入点;橙色线,C2 Cap域插入点。虚线,表示不完全存在于HAD超家族所有成员中的二级结构元素。源自文献[10]. (C) TmCel12A E134C突变体和底物纤维二糖的晶体结构,其A链与其他已知的GH12-家族酶叠加,红色显示,表明TmCel12A具有独特loop (A3-B3)源自文献[11].

酶骨架的可塑性同时赋予了催化功能的混杂性(Promiscuity)。来自南极假丝酵母的脂肪酶B (lipase B, CALB) 同时具有甘油三酯水解和催化Aza-Michael加成反应功能[12]。同时,骨架可塑性也会影响酶的热稳定性,通过对来源于海栖热袍菌的纤维素酶TmCel12A与同家族其他糖苷水解酶的晶体结构比较可以发现,该酶含有两个较长且高度扭转的β-链B8和B9,以及特有的环结构A3-B3 (图2C)。该环包含R60和Y61,这两个氨基酸通过氢键和堆叠作用力稳定底物,这些结构特征影响了该酶的高热稳定性[13]。

1.2 酶催化口袋的可塑性

相对于整个蛋白骨架,酶催化口袋大多包含loop结构,因此口袋的可塑性更强,方便我们利用 (半) 理性设计技术,通过重塑催化口袋来调控酶的催化功能。

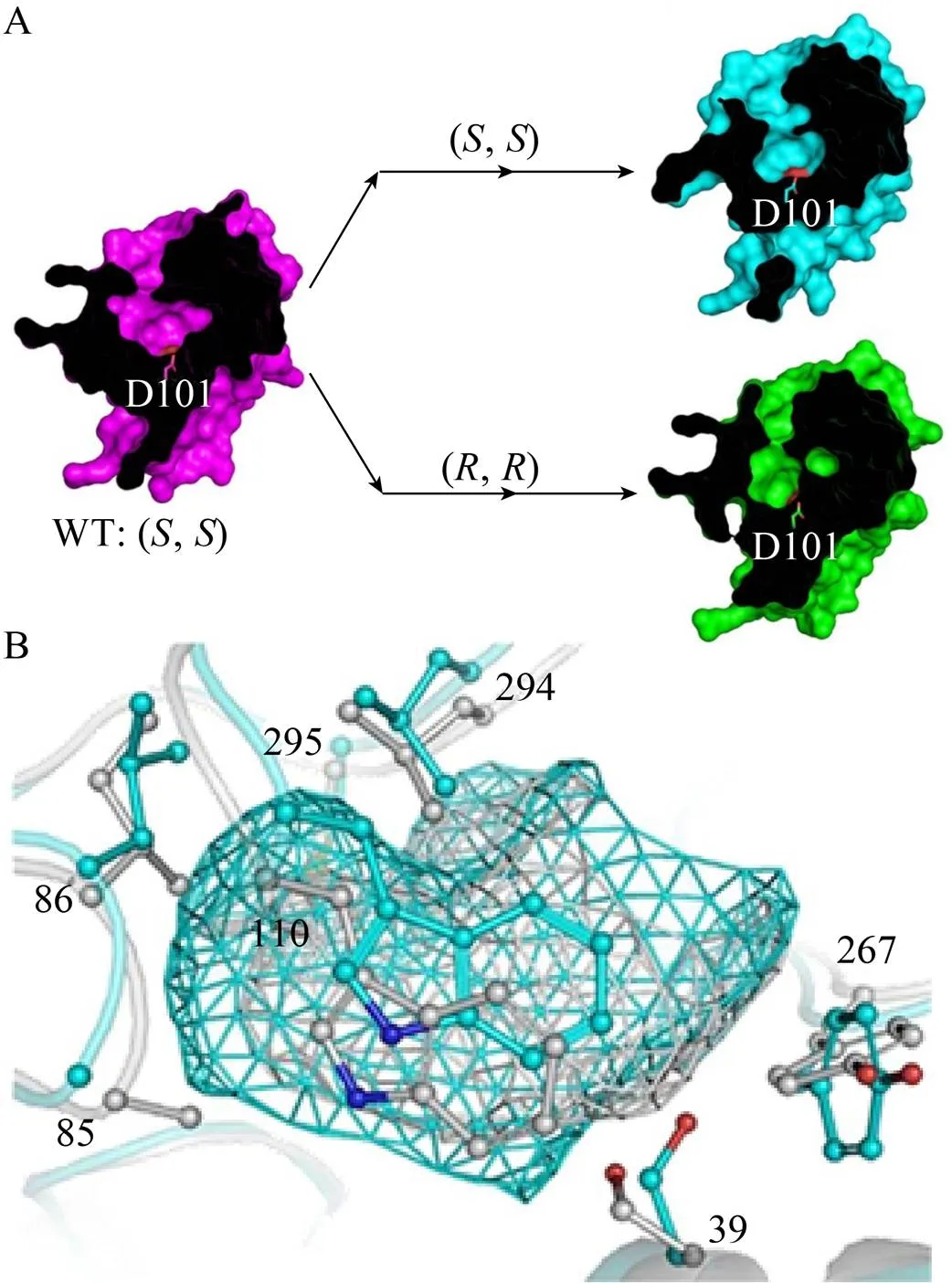

柠檬烯环氧水解酶LEH可不对称催化1,2-环氧己烷合成手性1,2-环己二醇。野生型 (Wild type, WT) LEH的立体选择性较差,倾向于 (,) 选择性。孙周通等经定向进化重塑酶催化口袋,获得的立体选择性提高及反转的最优突变体SZ348和SZ529,值分别达到99% (,) 和97% (,);晶体结构解析显示WT和两个突变体之间的整体结构差异非常小,但突变体SZ529和SZ348相对于WT的催化口袋构型发生了明显变化,尤其是手性反转的口袋构型变化比较明显(图3A)[14-15],并通过计算解析阐明了催化口袋的形状变化对其底物特异性和立体选择性的控制机制,并为LEH及相关工业用酶针对特异底物和不对称催化的定向设计改造提供了重要的理论基础[16]。

酶催化口袋氨基酸残基变构可影响催化活性。以嗜热厌氧菌来源的醇脱氢酶TbSADH为例,基于其晶体结构,分别在30 ℃和60 ℃下对该酶进行分子动力学 (Molecular dynamics, MD) 模拟,结果表明催化口袋内的A85、I86、L294及C295位点的运动自由度较差[17]。经虚拟突变分析,锁定85及86位点为重点改造对象,通过在这两个位点引入合适突变,最优突变体 (A85G/I86L) 相应loop区域柔性增强,相较WT,突变体催化口袋明显变大(图3B),进而实现了非天然前手性酮 (如重要医药中间体 (4-氯苯基) 吡啶-2-甲酮) 的不对称还原[17-18]。

图3 酶催化口袋的可塑性. (A)重塑LEH突变体催化口袋,源自文献[15].(B) TbSADH WT (灰色)和突变体T15 (青色) 催化小口袋的快照,源自文献[17].

另外,酶催化口袋loop区域的可塑性影响酶催化功能的混杂性。里氏木霉可分泌纤维二糖水解酶TrCel7A和内切葡聚糖酶TrCel7B,尽管这两个酶具有大约50%的氨基酸序列一致性且三维结构高度相似,然而两者功能相差很大,主要由覆盖其底物结合区域的loop环结构不同所造成[19]。

2 酶结构对其催化特性的影响

2.1 酶结构对稳定性的影响

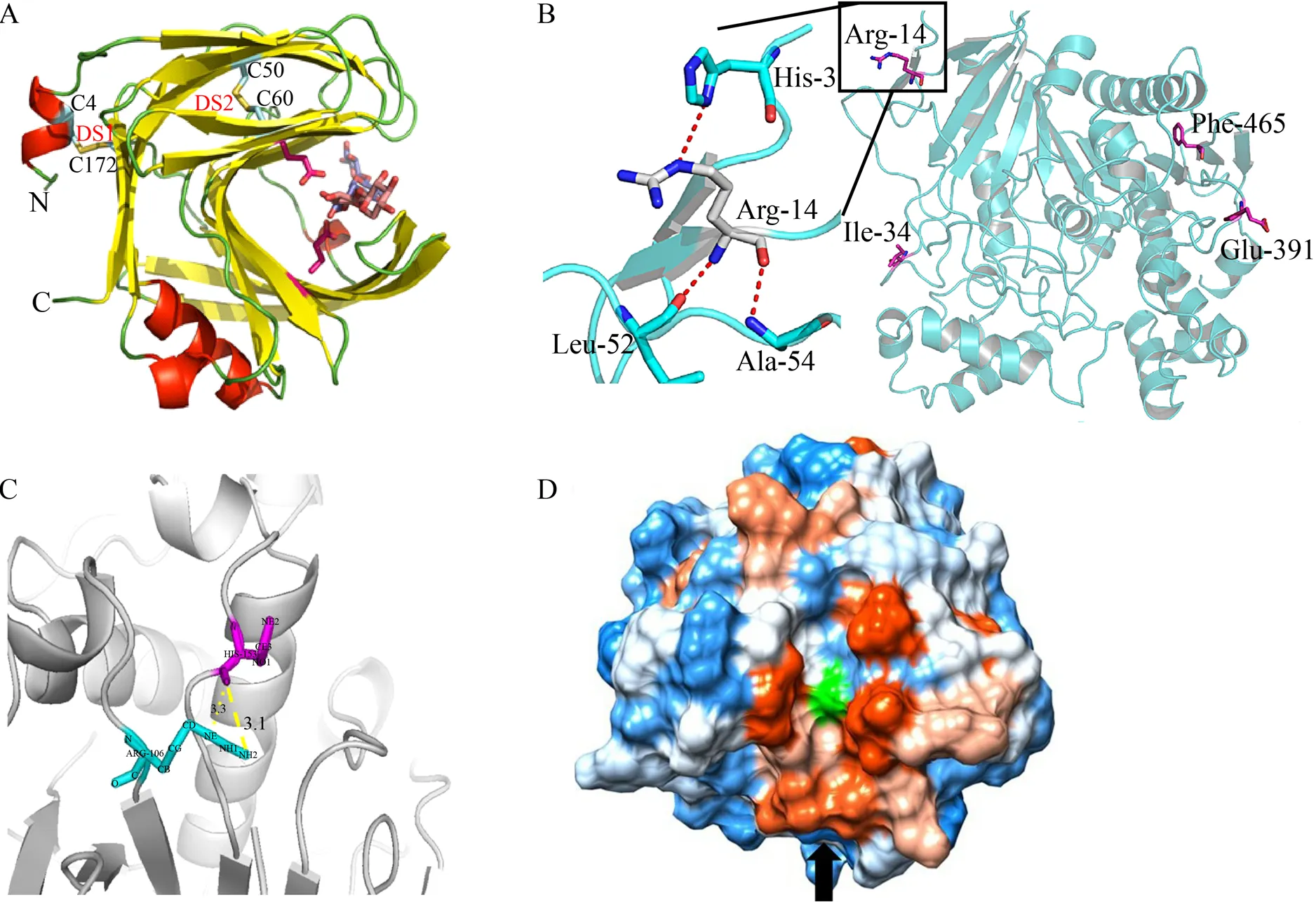

酶的稳定性包括热稳定性、抗氧化稳定性、pH稳定性和非水相溶剂耐受性等[20]。其中,二硫键、离子相互作用、氢键网络、极性相互作用等对酶的稳定性有重要影响 (图4)。

二硫键对酶的稳定性具有重要影响。来源于瘤胃厌氧真菌新美丝杆菌GH11家族的木聚糖酶,其整体结构为典型的GH11 β-jelly-roll折叠。催化区域N端的11个氨基酸为该酶特有结构,此片段通过氢键、芳香环堆叠作用及一个二硫键 (C4/C172) 固定在催化口袋。截短实验证明这11个氨基酸的存在与该酶的活性及热稳定性直接相关,并且C4和C172位点之间的二硫键是维持此片段结构的关键因素 (图4A)[21]。

离子相互作用对酶结构稳定性也有重要作用。枯草芽孢杆菌酯酶esterase突变体BSE V4在30 ℃的半衰期较WT提高了5.6倍,同源建模和分子对接发现,突变体相较于WT形成了新的氢键和离子键(红色虚线,图4B),有利于提高突变体的热稳定性[22]。酶结构中的氢键网络是维持结构稳定的重要因素。芽孢杆菌脂肪酶lipase R153H突变体的热稳定性较WT提高了72倍,结构分析表明H153和R106形成了额外氢键 (图4C)[23]。来源于长野芽孢杆菌的普鲁兰酶,在其稳定性改造实验中,突变体D787C能够在pH 4.0下保持90%活性。进一步分析发现D787C的氢键网络相对于WT发生了重组,导致相近的α-螺旋和loop区变构,影响底物分子与酶催化口袋的相互作用。同时D787C所在的loop区变得更加刚性,增加了突变体在酸性条件下的稳定性[25]。

图4 酶结构对其稳定性的影响. (A)源于Neocallimastix patriciarum GH11家族的木聚糖酶及底物的复合体晶体结构,两个二硫键分别用DS1, DS2表示,源自文献[21]. (B)BSE V4突变体模型及突变位点形成的氢键和离子键,源自文献[22]. (C) 突变体R153H中形成的额外氢键,His153/O (粉红色)与Arg106/NE和Arg106/NH 2 (青色),源自文献[23]. (D) 枯草芽孢杆菌脂肪酶A晶体结构展示。催化活性位点S77用绿色表示,其他氨基酸残基用从疏水 (橙色)到亲水 (蓝色)着色,源自文献[24].

酶特定位点氨基酸残基的极性/非极性对其在非水相溶剂中的稳定性具有重要调节作用。基于分子动力学模拟枯草芽孢杆菌脂肪酶A (lipase A) 离子液体耐受性机制研究,发现在底物结合口袋处引入带正电荷的氨基酸有利于提高其对15 vol%[Bmim] [TfO]离子液体的抗性,可能原因是带正电的氨基酸阻碍了[Bmin]+离子在催化口袋的聚集。同时,将该酶蛋白表面的氨基酸突变为极性氨基酸可更好地稳定表面水分子网络,进而提高其离子液体耐受性 (图4D)[24]。

酶结构刚柔性对其活力和稳定性具有重要影响。B因子 (又称为Debye-Waller因子,温度因子或原子位移参数) 是描述由热运动引起的X射线散射或相关中子散射的衰减的参数,能提供蛋白质分子局部的运动信息,反映蛋白质分子由于热振动和构象变化而引起的振动程度,可用于鉴定原子、侧链甚至整个区域的柔性[26]。借助B因子可研究生物大分子的内部运动和热力学稳定性,近期研究表明,降低酶结构柔性,有利于提高其稳定性[27];而增加催化口袋柔性可在一定程度上提高酶活 性[28]。近年来基于B因子开发的B-FIT定向进化策略,成功应用于热稳定性等酶性能改造[29]。

2.2 酶结构对催化选择性的影响

酶的立体/区域/化学选择性是其相较于化学催化剂的突出优势之一,酶的催化选择性受酶的结构,尤其是其催化口袋几何构象影响。

酶催化口袋的柔性对其立体选择性具有重要的调节作用。来源于克非尔乳杆菌的短链醇脱氢酶A94F和Y190F突变体,通过诱导催化口袋的构象变化,扩大结合口袋,促进在该区域容纳较大的硫原子并增强其催化3-硫代环戊酮还原的选择性 (图5A)[30]。

酶催化口袋氨基酸的位阻效应是决定其催化口袋形状的重要因素,同样可影响催化选择性。通过引入小体积氨基酸,可以降低来源于谷氨酸棒杆菌苏氨酸脱氨酶 (threonine deaminase,CgTD) 底物进入通道入口处氨基酸的位阻效应[31]。并且其突变体F114A/R229T催化3-苯基-L-丝氨酸脱氨活力相较于WT提高了18倍(图5B)。与之相反,通过引入大位阻氨基酸,理性设计CALB的醇基结合口袋的A281和A282位点,能缩小CALB的醇基结合口袋体积,使得双醇底物能够进入,但不接受单酯底物,达到选择性合成单酯的目的[32]。

酶催化的选择性也受其底物进入通道的影响,底物进入通道的形状往往决定其催化选择性[33]。例如,人胰脂肪酶的底物结合口袋在酶表面较浅的凹陷处,仅可容纳链长约8个碳原子的脂肪酸[34];而褶皱假丝酵母脂肪酶的底物结合口袋是22 Å长的隧道,能容纳链长达17个碳原子的脂肪酸 (图5C)[35],这些延伸结合位点的大小差异与底物特异性有关,特别是与它们水解的脂肪酸链长相关。

酶催化口袋的氨基酸残基与底物之间的相互作用也是影响催化选择性的重要因素。通过拉伸分子动力学模拟计算解析腈水合酶立体选择性,结果表明 ()-甘露腈必须打破和βHis37残基之间的氢键才能进入腈水合酶的催化口袋,提高腈水合酶的 ()-选择性[36]。通过分子动力学模拟TbSADH突变体I86A结构与功能的关系,发现该位点突变后,酶催化口袋的形状发生明显变化,底物与口袋非共价键相互作用增强 (绿色膜状,图5D),从而反转了TbSADH的立体选择性[37]。

图5 酶结构对催化选择性的影响. (A)构象动力学解析醇脱氢酶催化3-硫代环戊酮还原的立体选择性,源自文献[30]. (B)CgTD WT和F114A/R229T突变体的底物进入通道,源自文献[31]. (C) 人胰脂肪酶的底物结合口袋,源自文献[3]. (D)底物与突变体TbSADH I86A结合口袋非共价键相互作用 (绿色膜状),源自文献[37].

2.3 酶结构对催化活力的影响

酶的催化活性由其三维结构决定。来源于瘤胃厌氧真菌新美丝杆菌GH11家族的木聚糖酶具有高活性,有较好工业应用潜力。基于晶体结构解析,对该酶催化口袋关键位点进行突变,筛选获得双突变体W125F/F163W,其活力比WT提高了20%;此外,该酶在毕赤酵母系统中表达会比大肠杆菌中表达表现出更高的耐热性和活性,研究发现N端的糖基化是造成这一差异的主要原因[38]。

酶结构同样决定底物专一性。来自海栖热袍菌的超嗜热内切葡聚糖酶Cel5A,能催化以葡萄糖和甘露糖为主链的不同底物的多糖水解,被应用于木质纤维素生物燃料的合成。为研究该酶多重底物专一性,对其进行晶体结构解析,发现了Cel5A催化β-葡萄糖苷和β-甘露糖苷的高度保守的氨基酸残基E253和E136,同时还发现了一个特殊的开放式活性区,该区域可容纳具有支链的多糖底物,在这个开放活性区域中,底物葡萄糖或甘露糖的第2个碳上的氢氧基团不和活性区周围的氨基酸产生空间位阻,因而使其对不同的底物均具有较好活力[39]。表1总结了近年来通过酶结构改造优化其催化性能的部分报道。

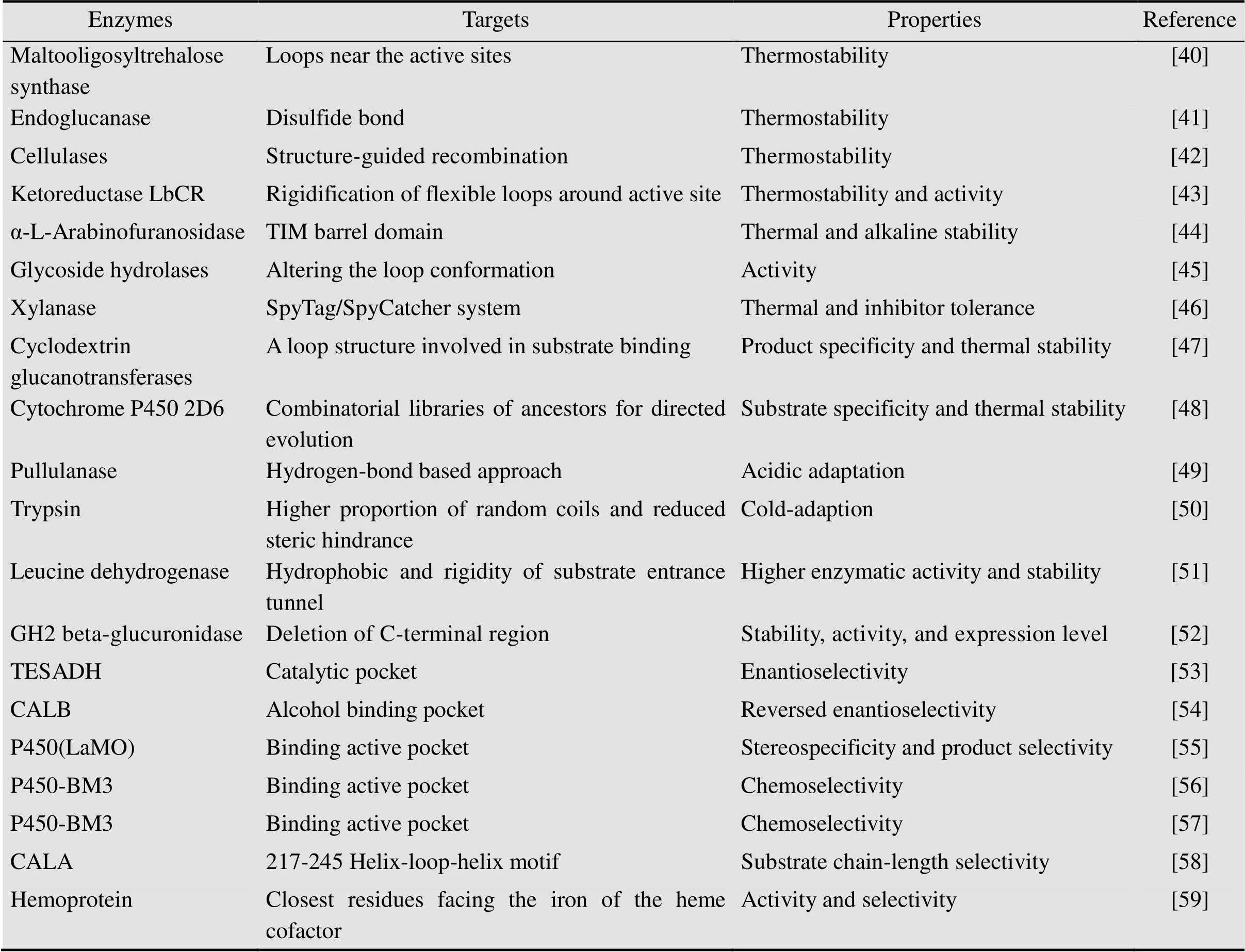

表1 酶结构改造优化催化性能部分实例

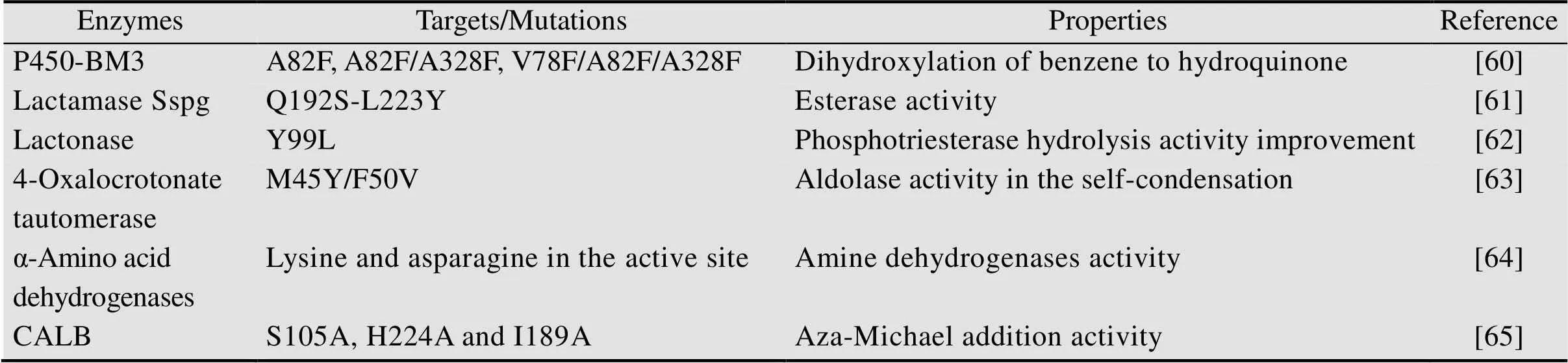

此外,酶结构改造还能够使其具有天然酶所不具备的催化功能 (表2)。例如,定向进化来源于巨大芽孢杆菌的P450-BM3使其具有羟化苯酚生成对羟基苯酚活力,且产物区域选择性>93%[60];γ-内酰胺酶Sspg可定向进化为对苯基缩水甘油酸底物具有高立体选择性的酯酶 (E值>300)[61]。

表2 酶结构改造赋予新功能部分实例

3 酶结构与功能关系研究方法

3.1 结构解析方法

常用的研究蛋白结构方法有X射线晶体衍射 (X-ray crystallography)、核磁共振 (Nuclear magnetic resonance,NMR) 以及冷冻电镜 (Cyro-electron microscope,Cyro-EM) 3种[66]。X-射线晶体衍射技术通过研究蛋白质晶体的衍射图谱,获得相应的结构信息,是目前最常用的解析蛋白结构的技术手段。截止2019年5月,蛋白质结构数据库PDB (Protein data bank) 共收录了152 151个生物大分子晶体结构,其中有13.5万个结构是通过X-射线衍射获得,1.2万个结构通过核磁共振获得,另外0.3万个结构则由冷冻电镜技术获得,这些海量晶体结构数据为研究酶的构效关系提供了很好的研究基础。

3.2 构效关系的计算分析方法

保守性分析是研究蛋白质构效关系的有效方法。超蛋白家族中同源蛋白的比较分析能够为酶结构与功能关系研究提供有价值信息。Mustguseal网络服务器可根据公共数据库中结构与序列的可用信息,自动构建功能多样性酶家族的大量晶体结构[67]。通过结构比对分析,可分析进化上的远亲、保守性氨基酸残基、亚家族特异性氨基酸残基及共同进化的氨基酸残基。以磷脂酶A2超蛋白家族为例,通过保守分析和氨基酸共进化网络分析鉴定其重要氨基酸残基,揭示了14个高度保守的位点和3组共进化的氨基酸残基[68]。

分子动力学模拟是一种经典动力学模拟分子运动的方法,是研究构效关系的有利工具。它的最大优势在于能揭示酶数据库中存储的静态结构之外的信息,还可通过提供分子动态相互作用直接指导酶设计。借助于近似攻击 (Near attach conformation, NAC) 理论,MD还可对突变体文库进行虚拟筛选,通过评估NAC构象的出现频率,对设计的突变体进行排名、选择、识别和评估[69]。

此外,量子力学(Quantum mechanics,QM) 及量子力学/分子力学 (QM/MM) 组合方法通过计算分子键能、几何构型、标准生成焓、偶极矩及电荷分布等性质,对酶的催化机制和反应过程进行计算解析,也是研究酶构效关系的主要应用方法[70-71]。

4 总结与展望

在自然界中经过数亿年进化,酶分子形成了复杂的结构以行使功能。1965年,David Phillips首次解析了溶菌酶的晶体结构[72],使科学家们能够从结构的角度去理解酶的功能。1977年,McCammon首次将分子动力学模拟应用于生物大分子[73],为酶结构内部运动对功能的影响研究提供信息。随后,通过Frances H. Arnold、Manfred T. Reetz等定向进化领域先驱开发的一系列酶设计改造技术[74-79],获得了大量催化功能和特性优化的突变酶,为酶结构与功能关系研究提供了素材。近年来,依赖计算模拟技术的进步,以David Baker为代表的科学家们开始从头设计蛋白质并赋予其新功能,已经取得了卓有成效的进展[80-81]。此外,基于酶的晶体结构解析,在计算机模拟技术协助下,开发高效进化策略,例如FRISM (Focused rational iterative site-specific mutagenesis) 技术[82]和机器学习[83-84]等,都是探究酶构效关系及设计改造的有利工具。

可以预见,随着人们对酶结构与功能关系认识的不断深入,设计满足工业生产需求的工具酶将变得更为普遍(关于工业酶设计改造方面的相关进展,笔者已在他文进行过评述[85-87])。同时当今人工智能技术正蓬勃发展,如何把握这一历史发展机遇,促使酶构效关系研究更加智能化、精准化,是未来本领域的一个重要研究方向。

[1] Ouzounis CA, Coulson RMR, Enright AJ, et al. Classification schemes for protein structure and function. Nat Rev Genet, 2003, 4(7): 508–519.

[2] Bartlett GJ, Porter CT, Borkakoti N, et al. Analysis of catalytic residues in enzyme active sites. J Mol Biol, 2002, 324(1): 105–121.

[3] Kingsley LJ, Lill MA. Substrate tunnels in enzymes: structure-function relationships and computational methodology. Proteins, 2015, 83(4): 599–611.

[4] Reetz MT, Carballeira JD. Iterative saturation mutagenesis (ISM) for rapid directed evolution of functional enzymes. Nat Protoc, 2007, 2(4): 891–903.

[5] Jimenez-Rosales A, Flores-Merino MV. Tailoring proteins to re-evolve nature: a shortreview. Mol Biotechnol, 2018, 60(12): 946–974.

[6] Gahloth D, Dunstan MS, Quaglia D, et al. Structures of carboxylic acid reductase reveal domain dynamics underlying catalysis. Nat Chem Biol, 2017, 13(9): 975–981.

[7] Qu G, Guo JG, Yang DM, et al. Biocatalysis of carboxylic acid reductases: phylogenesis, catalytic mechanism and potential applications. Green Chem, 2018, 20(4): 777–792.

[8] Qu G, Fu MX, Zhao LL, et al. Computational insights into the catalytic mechanism of bacterial carboxylic acid reductase. J Chem Inf Model, 2019, 59(2): 832–841.

[9] Bashton M, Chothia C. The generation of new protein functions by the combination of domains. Structure, 2007, 15(1): 85–99.

[10] Burroughs AM, Allen KN, Dunaway-Mariano D, et al. Evolutionary genomics of the had superfamily: understanding the structural adaptations and catalytic diversity in a superfamily of phosphoesterases and allied enzymes. J Mol Biol, 2006, 361(5): 1003–1034.

[11] Cheng YS, Ko TP, Wu TH, et al. Crystal structure and substrate-binding mode of cellulase 12A from. Proteins, 2011, 79(4): 1193–1204.

[12] Gupta RD. Recent advances in enzyme promiscuity. Sustain Chem Proc, 2016, 4(1): 2.

[13] Cheng YS, Ko TP, Huang JW, et al. Enhanced activity ofcellulase 12A by mutating a unique surface loop. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2012, 95(3): 661–669.

[14] Sun ZT, Lonsdale R, Kong XD, et al. Reshaping an enzyme binding pocket for enhanced and inverted stereoselectivity: use of smallest amino acid alphabets in directed evolution. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2015, 54(42): 12410–12415.

[15] Sun ZT, Lonsdale R, Wu L, et al. Structure-guided triple-code saturation mutagenesis: efficient tuning of the stereoselectivity of an epoxide hydrolase. ACS Catal, 2016, 6(3): 1590–1597.

[16] Sun ZT, Wu L, Bocola M, et al. Structural and computational insight into the catalytic mechanism of limonene epoxide hydrolase mutants in stereoselective transformations. J Am Chem Soc, 2018, 140(1): 310–318.

[17] Liu BB, Qu G, Li JK, et al. Conformational dynamics-guided loop engineering of an alcohol dehydrogenase: capture, turnover and enantioselective transformation of difficult-to-reduce ketones. Adv Synth Catal, 2019, 361(13): 3182–3190.

[18] Qu G, Liu BB, Jiang YY, et al. Laboratory evolution of an alcohol dehydrogenase towards enantioselective reduction of difficult-to-reduce ketones. Bioresour Bioprocess, 2019, 6(1): 18.

[19] Schiano-di-Cola C, Rojel N, Jensen K, et al. Systematic deletions in the cellobiohydrolase (CBH) Cel7A from the fungusreveal flexible loops critical for CBH activity. J Biol Chem, 2019, 294(6): 1807–1815.

[20] Balcão VM, Vila M. Structural and functional stabilization of protein entities:---. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2015, 93: 25–41.

[21] Cheng YS, Chen CC, Huang CH, et al. Structural analysis of a glycoside hydrolase family 11 xylanase from: insights into the molecular basis of a thermophilic enzyme. J Biol Chem, 2014, 289(16): 11020–11028.

[22] Gong Y, Xu GC, Zheng GW, et al. A thermostable variant ofesterase: characterization and application for resolving dl-menthyl acetate. J Mol Catal B-Enzym, 2014, 109: 1–8.

[23] Chopra N, Kaur J. Point mutation Arg153-His at surface oflipase contributing towards increased thermostability and ester synthesis: insight into molecular network. Mol Cell Biochem, 2018, 443(1/2): 159–168.

[24] Zhao J, Frauenkron-Machedjou VJ, Fulton A, et al. Unraveling the effects of amino acid substitutions enhancing lipase resistance to an ionic liquid: a molecular dynamics study. Phys Chem Chem Phys, 2018, 20(14): 9600–9609.

[25] Wang XY, Nie Y, Xu Y. Improvement of the activity and stability of starch-debranching pullulanase fromvia tailoring of the active sites lining the catalytic pocket. J Agric Food Chem, 2018, 66(50): 13236–13242.

[26] Zhang H, Zhang T, Chen K, et al. On the relation between residue flexibility and local solvent accessibility in proteins. Proteins, 2009, 76(3): 617–636.

[27] Kim HS, Le QAT, Kim YH. Development of thermostable lipase B from(CalB) throughdesign employing B-factor and RosettaDesign. Enzyme Microb Technol, 2010, 47(1/2): 1–5.

[28] Hong SY, Yoo YJ. Activity enhancement oflipase b by flexibility modulation in helix region surrounding the active site. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2013, 170(4): 925–933.

[29] Sun ZT, Liu Q, Qu G, et al. Utility of B-factors in protein science: interpreting rigidity, flexibility, and internal motion and engineering thermostability. Chem Rev, 2019, 119(3): 1626–1665.

[30] Noey EL, Tibrewal N, Jiménez-Osés G, et al. Origins of stereoselectivity in evolved ketoreductases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(51): E7065–E7072.

[31] Song W, Wang JH, Wu J, et al. Asymmetric assembly of high-value α-functionalized organic acids using a biocatalytic chiral-group-resetting process. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 3818.

[32] Hamberg A, Maurer S, Hult K. Rational engineering oflipase B for selective monoacylation of diols. Chem Commun, 2012, 48(80): 10013–10015.

[33] Kreß N, Halder JM, Rapp LR, et al. Unlocked potential of dynamic elements in protein structures: channels and loops. Curr Opin Chem Biol, 2018, 47: 109–116.

[34] Pleiss J, Fischer M, Schmid RD. Anatomy of lipase binding sites: the scissile fatty acid binding site. Chem Phys Lipids, 1998, 93(1/2): 67–80.

[35] Grochulski P, Bouthillier F, Kazlauskas RJ, et al. Analogs of reaction intermediates identify a unique substratebinding site inlipase. Biochemistry, 1994, 33(12): 3494–3500.

[36] Cheng ZY, Peplowski L, Cui WJ, et al. Identification of key residues modulating the stereoselectivity of nitrile hydratase toward rac-mandelonitrile by semi-rational engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2018, 115(3): 524–535.

[37] Maria-Solano MA, Romero-Rivera A, Osuna S. Exploring the reversal of enantioselectivity on a zinc-dependent alcohol dehydrogenase. Org Biomol Chem, 2017, 15(19): 4122–4129.

[38] Cheng YS, Chen CC, Huang JW, et al. Improving the catalytic performance of a GH11 xylanase by rational protein engineering. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2015, 99(22): 9503–9510.

[39] Wu TH, Huang CH, Ko TP, et al. Diverse substrate recognition mechanism revealed byCel5A structures in complex with cellotetraose, cellobiose and mannotriose. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2011, 1814(12): 1832–1840.

[40] Chen C, Su LQ, Xu F, et al. Improved thermostability of maltooligosyltrehalose synthase fromby directed evolution and site-directed mutagenesis. J Agric Food Chem, 2019, 67(19): 5587–5595.

[41] Bashirova A, Pramanik S, Volkov P, et al. Disulfide bond engineering of an endoglucanase fromto improve its thermostability. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(7): 1602.

[42] Zheng F, Vermaas JV, Zheng J, et al. Activity and thermostability of gh5 endoglucanase chimeras from mesophilic and thermophilic parents. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2019, 85(5): e02079-18.

[43] Gong XM, Qin Z, Li FL, et al. Development of an engineered ketoreductase with simultaneously improved thermostability and activity for making a bulky atorvastatin precursor. ACS Catal, 2019, 9(1): 147–153.

[44] Surmeli Y, İlgüH, Şanlı-Mohamed G. Improved activity of α-L-arabinofuranosidase fromGS90 by directed evolution: investigation on thermal and alkaline stability. Biotechnol Appl Biochem, 2019, 66(1): 101–107.

[45] Chen JJ, Liang X, Chen TJ, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of a β-glycoside hydrolase from. Molecules, 2019, 24(1): 59.

[46] Sun XB, Cao JW, Wang JK, et al. SpyTag/SpyCatcher molecular cyclization confers protein stability and resilience to aggregation. New Biotechnol, 2019, 49: 28–36.

[47] Sonnendecker C, Zimmermann W. Change of the product specificity of a cyclodextrin glucanotransferase by semi-rational mutagenesis to synthesize large-ring cyclodextrins. Catalysts, 2019, 9(3): 242.

[48] Gumulya Y, Huang WL, D’Cunha SA, et al. Engineering thermostable CYP2D enzymes for biocatalysis using combinatorial libraries of ancestors for directed evolution (CLADE). ChemCatChem, 2019, 11(2): 841–850.

[49] Chen A, Xu TT, Ge Y, et al. Hydrogen-bond-based protein engineering for the acidic adaptation ofpullulanase. Enzyme Microb Technol, 2019, 124: 79–83.

[50] Zhou TT, Wang XC, Yan J, et al. Gene analysis and structure prediction for the cold-adaption mechanism of trypsin from the krill(Dana, 1852). J Sci Food Agric, 2018, 98(8): 3049–3056.

[51] Zhou JP, Wang YL, Chen JJ, et al. Rational engineering ofleucine dehydrogenase towards α-keto acid reduction for improving unnatural amino acid production. Biotechnol J, 2019, 14(3): 1800253.

[52] Han BJ, Hou YH, Jiang T, et al. Computation-aided rational deletion of c-terminal region improved the stability, activity, and expression level of GH2 β-glucuronidase. J Agric Food Chem, 2018, 66(43): 11380–11389.

[53] Musa MM, Ziegelmann-Fjeld KI, Vieile C, et al. Asymmetric reduction and oxidation of aromatic ketones and alcohols using W110A secondary alcohol dehydrogenase from. J Org Chem, 2007, 72(1): 30–34.

[54] Cen YX, Li DY, Xu J, et al. Highly focused library-based engineering oflipase b with ()-selectivity towards-alcohols. Adv Synth Catal, 2019, 361(1): 126–134.

[55] Li RJ, Li AT, Zhao J, et al. Engineering P450LaMOstereospecificity and product selectivity for selective C-H oxidation of tetralin-like alkylbenzenes. Catal Sci Technol, 2018, 8(18): 4638–4644.

[56] Dennig A, Weingartner AM, Kardashliev T, et al. An enzymatic route to α-tocopherol synthons: aromatic hydroxylation of pseudocumene and mesitylene with P450 BM3. Chemistry, 2017, 23(71): 17981–17991.

[57] Wang JB, Ilie A, Reetz MT. Chemo- and stereoselective cytochrome P450-BM3-catalyzed sulfoxidation of 1-thiochroman-4-ones enabled by directed evolution. Adv Synth Catal, 2017, 359(12): 2056–2060.

[58] Quaglia D, Alejaldre L, Ouadhi S, et al. Holistic engineering of Cal-A lipase chain-length selectivity identifies triglyceride binding hot-spot. PLoS ONE, 2019, 14(1): e0210100.

[59] Cho I, Prier CK, Jia ZJ, et al. Enantioselective aminohydroxylation of styrenyl olefins catalyzed by an engineered hemoprotein. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2019, 58(10): 3138–3142.

[60] Zhou HY, Wang BJ, Wang F, et al. Chemo- and regioselective dihydroxylation of benzene to hydroquinone enabled by engineered cytochrome P450 monooxygenase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2019, 58(3): 764–768.

[61] Wang JJ, Zhao HT, Zhao GG, et al. Enhancing the atypical esterase promiscuity of the γ-lactamase Sspg fromby substrate screening. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2019, 103(10): 4077–4087.

[62] Zhang Y, An J, Yang GY, et al. Active site loop conformation regulates promiscuous activity in a lactonase fromHTA426. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10(2): e0115130.

[63] Rahimi M, van der Meer JY, Geertsema EM, et al. Engineering a promiscuous tautomerase into a more efficient aldolase for self-condensations of linear aliphatic aldehydes. ChemBioChem, 2017, 18(14): 1435–1441.

[64] Tseliou V, Masman MF, Böhmer W, et al. Mechanistic insight into the catalytic promiscuity of amine dehydrogenases: asymmetric synthesis of secondary and primary amines. ChemBioChem, 2019, 20(6): 800–812.

[65] Gu B, Hu ZE, Yang ZJ, et al. Probing the mechanism of CAL-B-catalyzed aza-michael addition of aniline compounds with acrylates using mutation and molecular docking simulations. Chemistryselect, 2019, 4(13): 3848–3854.

[66] Jaskolski M, Dauter Z, Wlodawer A. A brief history of macromolecular crystallography, illustrated by a family tree and its Nobel fruits. FEBS J, 2014, 281(18): 3985–4009.

[67] Suplatov DA, Kopylov KE, Popova NN, et al. Mustguseal: a server for multiple structure-guided sequence alignment of protein families. Bioinformatics, 2018, 34(9): 1583–1585.

[68] Oliveira A, Bleicher L, Schrago CG, et al. Conservation analysis and decomposition of residue correlation networks in the phospholipase A2 superfamily (PLA2s): insights into the structure-function relationships of snake venom toxins. Toxicon, 2018, 146: 50–60.

[69] Childers MC, Daggett V. Insights from molecular dynamics simulations for computational protein design. Mol Syst Des Eng, 2017, 2(1): 9–33.

[70] Senn HM, Thiel W. QM/MM studies of enzymes. Curr Opin Chem Biol, 2007, 11(2): 182–187.

[71] Kulik HJ. Large-scale QM/MM free energy simulations of enzyme catalysis reveal the influence of charge transfer. Phys Chem Chem Phys, 2018, 20(31): 20650–20660.

[72] Blake CCF, Koenig DF, Mair GA, et al. Structure of hen egg-white lysozyme: a three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 Å resolution. Nature, 1965, 206(4986): 757–761.

[73] McCammon JA, Gelin BR, Karplus M. Dynamics of folded proteins. Nature, 1977, 267(5612): 585–590.

[74] Chen K, Arnold FH. Tuning the activity of an enzyme for unusual environments: sequential random mutagenesis of subtilisin E for catalysis in dimethylformamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1993, 90(12): 5618–5622.

[75] Reetz MT, Bocola M, Carballeira JD, et al. Expanding the range of substrate acceptance of enzymes: combinatorial active-site saturation test. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2005, 44(27): 4192–4196.

[76] Qu G, Li AT, Acevedo-Rocha CG, et al. The crucial role of methodology development in directed evolution of selective enzymes. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2019, doi: 10.1002/anie.201901491.

[77] Li AT, Qu G, Sun ZT, et al. Statistical analysis of the benefits of focused saturation mutagenesis in directed evolution based on reduced amino acid alphabets. ACS Catal, 2019, 9(9): 7769–7778.

[78] Acevedo-Rocha CG, Sun ZT, Reetz MT. Clarifying the difference between iterative saturation mutagenesis as a rational guide in directed evolution and OmniChange as a gene mutagenesis technique. ChemBioChem, 2018, 19 (24): 2542–2544.

[79] Sun ZT, Wikmark Y, Bäckvall J-E, et al. New concepts for increasing the efficiency in directed evolution of stereoselective enzymes. Chem Eur J, 2016, 22(15): 5046–5054.

[80] Jiang L, Althoff EA, Clemente FR, et al. De novo computational design of retro-aldol enzymes. Science, 2008, 319(5868): 1387–1391.

[81] Chen ZB, Boyken SE, Jia MX, et al. Programmable design of orthogonal protein heterodimers. Nature, 2019, 565(7737): 106–111.

[82] Xu J, Cen YX, Singh W, et al. Stereodivergent protein engineering of a lipase to access all possible stereoisomers of chiral esters with two stereocenters. J Am Chem Soc, 2019, 141(19): 7934–7945.

[83] Wu Z, Kan SBJ, Lewis RD, et al. Machine learning-assisted directed protein evolution with combinatorial libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2019, 11(6): 8852–8858.

[84] Li GY, Dong YJ, Reetz MT. Can machine learning revolutionize directed evolution of selective enzymes? Adv Synth Catal, 2019, 361(11): 2377–2386.

[85] Qu G, Zhao J, Zheng P, et al. Recent advances in directed evolution. Chin J Biotech, 2018, 34(1): 1–11 (in Chinese).曲戈, 赵晶, 郑平, 等. 定向进化技术的最新进展. 生物工程学报, 2018, 34(1): 1–11.

[86] Qu G, Zhang K, Jiang YY, et al. The Nobel Prize in chemistry 2018: the directed evolution of enzymes and the phage display technologies. J Biol, 2019, 36(1): 1–6 (in Chinese).曲戈, 张锟, 蒋迎迎, 等. 2018诺贝尔化学奖:酶定向进化与噬菌体展示技术. 生物学杂志, 2019, 36(1): 1–6.

[87] Qu G, Zhu T, Jiang YY, et al. Protein engineering: from directed evolution to computational design. Chin J Biotech, 2019, 35(10): 1843–1856. DOI: 10.13345/j.cjb.190221 (in Chinese).曲戈, 朱彤, 蒋迎迎, 等. 蛋白质工程:从定向进化到计算设计. 生物工程学报, 2019, 35(10): 1843–1856. DOI: 10.13345/j.cjb.190221.

Structure-function relationships of industrial enzymes

Kun Zhang*, Ge Qu*, Weidong Liu, and Zhoutong Sun

,,300308,

Industrial enzymes are the “chip” of modern bio-industries, supporting tens- and hundreds-fold of downstream industries development. Elucidating the relationships between enzyme structures and functions is fundamental for industrial applications. Recently, with the advanced developments of protein crystallization and computational simulation technologies, the structure-function relationships have been extensively studied, making the rational design anddesign become possible. This paper reviews the progress of structure-function relationships of industrial enzymes and applications, and address future developments.

industrial enzymes, structure-function, structural flexibility, biocatalysis

10.13345/j.cjb.190222

刘卫东 博士,中国科学院天津工业生物技术研究所副研究员,主要从事酶类催化剂的机理研究及性能改造工作。利用X射线晶体学手段,对有潜在应用价值的酶类催化剂进行催化机制研究;在此基础上,通过理性、半理性设计以改进酶的效能,如拓展底物谱、提高酶活、耐温性能等,以增强工业应用潜能。在、等SCI期刊上发表研究论文20余篇。

张锟, 曲戈, 刘卫东, 等. 工业酶结构与功能的构效关系. 生物工程学报, 2019, 35(10): 1806–1818.

Zhang K, Qu G, Liu WD, et al. Structure-function relationships of industrial enzymes. Chin J Biotech, 2019, 35(10): 1806–1818.

May 29, 2019;

September 23, 2019

Supported by: CAS Pioneer Hundred Talents Program (No. 2016-053).

Weidong Liu. Tel: +86-22-24828704; E-mail: liu_wd@tib.cas.cn

*These authors contributed equally to this study.

中国科学院率先行动“百人计划”项目 (No. 2016-053)资助。

2019-10-21

http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1998.Q.20191021.1128.001.html

(本文责编 郝丽芳)