Os calcis lipoma: To graft or not to graft? - A case report and literature review

Theodoros Balbouzis, Theodosios Alexopoulos, Peter Grigoris

Theodoros Balbouzis, Peter Grigoris, Department of Orthopaedics, Metropolitan General Hospital, Holargos, Athens 15562, Greece

Theodosios Alexopoulos, Department of Radiology, Metropolitan General Hospital, Holargos,Athens 15562, Greece

Abstract

Key words: Benign bone tumor; Os calcis lipoma; Calcaneus; Intraosseous lipoma; Bone graft; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Intraosseous lipoma is a rare benign tumor, with an estimated prevalence of around 0.1% of primary bone tumors[1,2]. The os calcis is affected in up to 63% of lesions, with the rest presenting in long bones[3,4]. Because many cases remain undetected, it can be assumed that its actual prevalence may be significantly higher than estimated. Most authors accept that this lesion represents a true benign bone tumor or even a unicameral bone cyst, whose fluid content has been replaced with adipose tissue[1,5-7].Others suggest an ischemic etiology, with subsequent necrosis of bone, leading to adipose metaplasia, or point towards a posttraumatic bone reaction[2,5,8]. It has also been proposed that a lipoma in the os calcis represents a well-defined “normal”radiolucency in Ward’s neutral triangle, where it is invariably located. This is an unloaded area at the base of the neck of the os calcis, bounded by the compressive and tensile lines of biomechanical stress[5,9]. As predicted by Wolff’s law, stress-shielding in this area leads to a paucity of trabeculae, which are replaced with adipose tissue[10,11]. It is postulated that in some individuals this process may be more pronounced, leading to the development of a radiographically detectable pseudocyst[5,9,12]. Symptomatic cases present with dull pain at rest and soft tissue swelling. At least one third of the cases are asymptomatic and are discovered incidentally in radiological investigations,conducted for an injury or for unrelated disorders[13].

There is no consensus, regarding the optimal treatment of an os calcis lipoma. The proponents of conservative treatment claim that spontaneous resolution of symptoms may occur[14]. Those favoring operative treatment recommend curettage of the cyst and application of bone graft or substitutes, particularly when the lesion is large or painful[15-17]. Most reports of operative treatment show resolution of symptoms and consolidation of the bone grafts[8,18-21]. We present the case of a patient treated with curettage and application of bone graft, who demonstrated almost complete resorption of the impacted material.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 56-year-old, otherwise healthy, Caucasian male attended the outpatient clinic of another institution in November 2011. He presented with a three-month history of increasing pain in his right heel, as a result of which he had to give up running.

Imaging and diagnosis

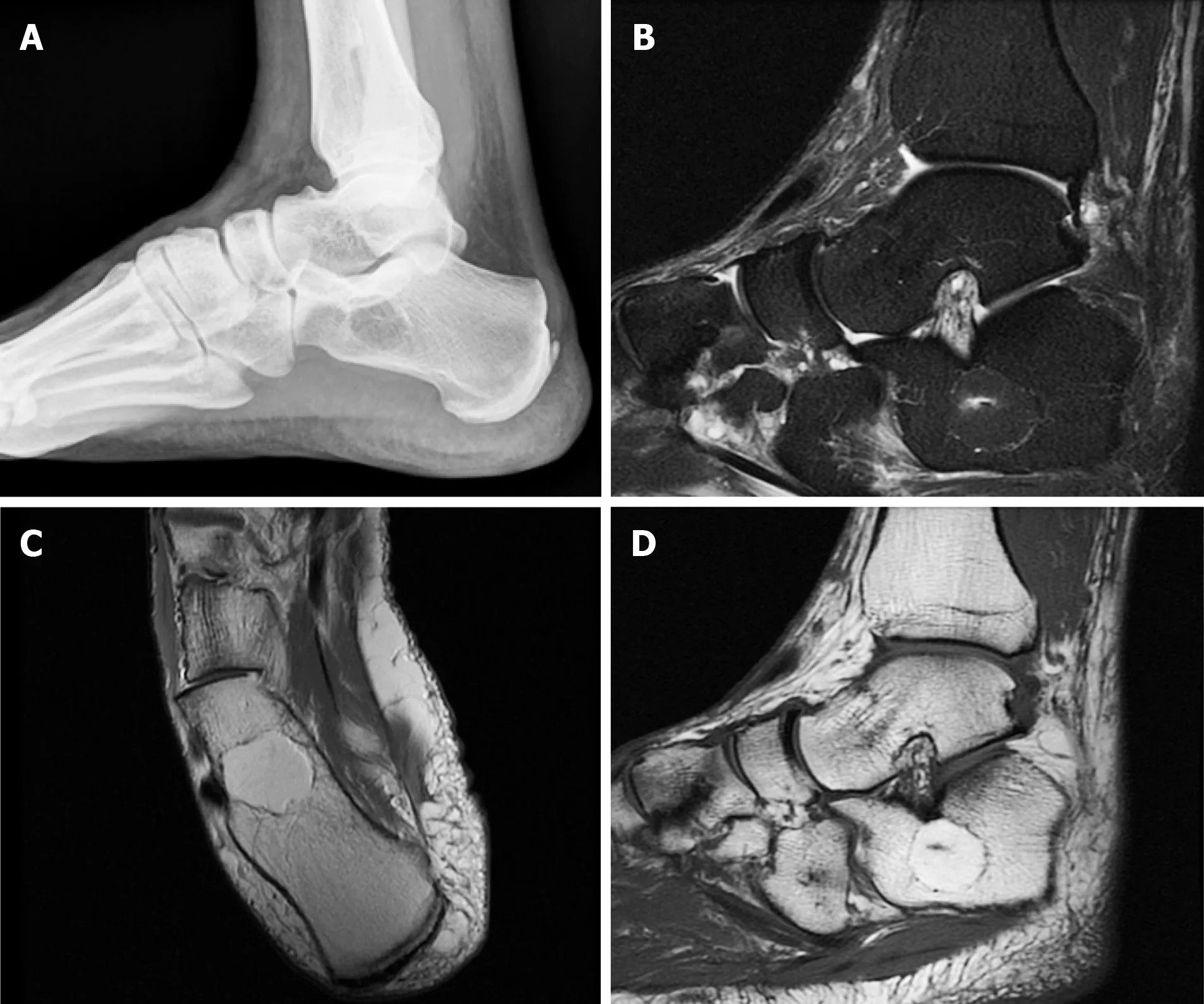

Radiographic investigation and computed tomography (CT) at that time, revealed a hypodense cystic area with a central calcification in Ward’s triangle of the os calcis(Figure 1A). The lesion had a diameter of 18.7 mm and extended between the superior and the inferior calcaneal cortex. The borders were well demarcated and the periphery of the area was filled with a meshwork of fine bone trabeculae. A linear hyperdense area appeared at the center of this lytic lesion. The lesion did not show any evidence of fracture or expansion in the soft tissues. Magnetic resonance imaging(MRI) showed a homogeneous high intensity signal on T1 weighting and fat suppression on T2 short tau inversion recovery sequence (STIR). In the center of the lesion, a linear area was apparent, with low-intensity signal on T1 sequence and high intensity on STIR sequences (Figure 1B-D).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Figure 1 Preoperative imaging of the os calcis lipoma. A: Initial radiographic presentation. B: T2 STIR sequence magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image, sagittal view. Fat suppression is presented at the area of the lesion, with high intensity linear signal at the center. No fracture or expansion into the soft tissues was identified. C: T1 sequence MRI, transverse view. D: Sagittal view. Sharply demarcated lesion with homogeneous high intensity signal at Ward’s neutral triangle, with linear low intensity signal at the center. The high signal denotes lipid content of the lesion,whereas the central low intensity signal is compatible with local infarction and necrosis.

Based on the characteristic radiological findings, a diagnosis of intraosseous lipoma was made.

TREATMENT

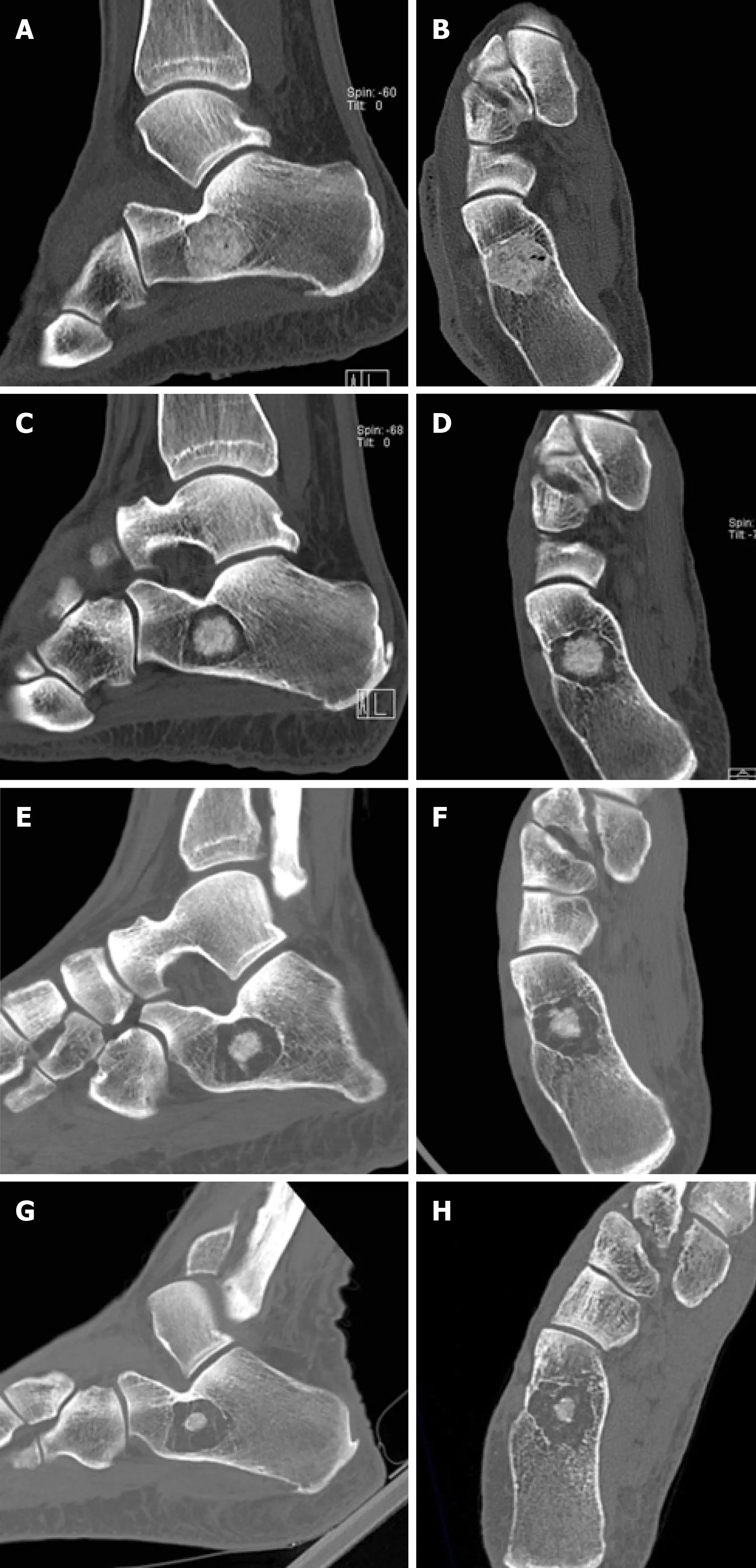

Operative treatment of the lesion was decided. With the guidance of an image intensifier, the os calcis was exposed with a lateral approach and a window was opened in the lateral cortex of the calcaneus with an osteotome. A significant amount of yellow, fatty tissue was encountered and was sent for microbiological and histopathological examination. No fracture was identified. The cavity was curetted to bleeding bone and subsequently filled with impacted crushed allograft and demineralized bone matrix (Orthoblend, Osteotech, Eatontown, NJ, United States)(Figure 2A and B). The wound was treated in the usual manner and a postoperative shoe was used for weight protection.

Laboratory examinations – Cultures and histology

The cultures were sterile. Histological examination of the extracted material revealed abundant mature adipose tissue, interspersed with sparse, thin, osseous trabeculae.Vascularity was poor. Areas of amorphous calcific deposits were seen, with scattered ghost outlines of necrotic lipocytes and with prominent histiocyte infiltration. Cellular atypia was not identified. This picture was compatible with the initial diagnosis of an intraosseous lipoma.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Six months postoperatively, the patient was free of pain and returned to recreational long distance running. However, a new CT revealed resorption of the margins of the bone graft (Figure 2C and D). Fifteen months postoperatively, the patient was examined, for the first time by our team, for slight pain of about two-month durationin his right heel. The pain was felt mostly with the first steps in the morning and after prolonged standing, and responded to oral non-steroidal analgesics. Apart from the operation at his heel, his medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination revealed a well-healed surgical scar at the lateral surface of the heel. No swelling,inflammation or palpable masses were evident. There was tenderness on palpation of the plantar surface of the heel. The patient was able to walk with no limp. The range of active and passive motion of all the joints of the lower limb was normal. Passive extension of the first toe while standing (windlass test) elicited slight pain.Neurological examination was unremarkable. Blood tests, including routine metabolic and rheumatologic assays and markers of infection, were normal. A diagnosis of plantar fasciitis was established. However, due to his previous operation, a new foot CT was obtained. When compared to the images taken six months postoperatively, it was evident that the hypodense area at the periphery of the lesion had expanded considerably (Figure 2E and F).

Figure 2 Serial computed tomography evaluation of os calcis lesion. A and B: Computed tomography images immediately postoperatively. Complete filling of the cavity has been obtained with bone graft. C and D: Six months postoperatively, circumferential graft absorption is present. E and F: Fifteen months postoperatively, further graft absorption is noted. G and H: At five years, the greatest part of the bone graft has been resorbed. A mesh of thin osseous septa is seen around the remaining bone graft. The lesion has not expanded since the first postoperative image.

The patient was reassured that his heel pain was probably unrelated to the previous pathology. Conservative treatment was chosen, with heel pads and followup as necessary. On his latest follow-up, five years postoperatively, the patient was free of symptoms. However, a new CT showed further resorption of the implanted graft(Figure 2G and H).

DISCUSSION

In plain radiographs, an intraosseous lipoma presents as an osteolytic lesion with marginal sclerosis. There is often central calcification, corresponding histologically to localized infarction and necrosis[5,8,20]. Typically, a CT shows a well circumscribed,non-expansile, osteolytic lesion with negative Hounsfield units, corresponding to the values for subcutaneous fat[22]. Marginal sclerosis is always present[22]. MRI can be helpful for the confirmation of presence of adipose tissue in the tumor by presenting homogeneous high intensity signal on T1 sequences and low intensity on fatsuppression, similar to those of the subcutaneous tissue[23]. The characteristic presentation, using these imaging modalities, usually obviates biopsy and histological evaluation.

The treatment of an os calcis lipoma should be decided on an individual basis. Most authors agree that an intraosseous lipoma of the os calcis can be managed with watchful waiting[3,9,14,24,25]. It is understood that pain may not be caused by the lesion itself but rather by unrelated pathology from the surrounding soft tissues or a nearby joint[5]. Surgical treatment is reserved for patients with persistent pain, related to the lesion, or indeed large lesions[15-19,25]. However, Tscherne et al[14]observed in their patients that heel pain can persist after curettage and grafting. Based on this observation, they reserved operative treatment for heel pain not responding to conservative treatment or for biopsy, in cases with atypical radiological presentation.

The possible association of the size of a cystic lesion with a subsequent pathological fracture has been an issue of concern. In a series of 50 os calcis cysts, Pogoda et al[16]reported four patients with fractures on presentation. These fractures were all associated with large lesions. The authors proposed a “critical size”, occupying the entire distance from the medial to the lateral cortex and at least 30% of the anteroposterior dimension. They concluded that cystic lesions exceeding this critical size should be managed surgically[16]. Nevertheless, in a meta-analysis of 54 cases with os calcis lipoma, Bertram et al[24]did not find any reported fractures. Also, in a literature review in 2014, Pappas et al[19]identified only two reported cases with calcaneal fracture associated with an intraosseous lipoma. It can be postulated that the presence of a cavity at this normally hypodense area is less significant for bone strength and only rarely leads to fractures under physiological loading.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a surgically treated os calcis lipoma,showing spectacular graft resorption in long-term radiological follow-up, despite the resolution of clinical symptoms. Most patient series on the surgical treatment of intraosseous lipoma have reported satisfactory pain relief and graft incorporation[7,8,18,21,25,26]. However, authors relied on plain radiographs for postoperative imaging. Unavailability of data from CT for follow-up represents a significant limitation of these studies.

The incorporation of graft, implanted in bone defects, represents a complex process,which depends upon various biological and biomechanical factors. Ischemia in the margins of the grafted cavity can adversely affect the integration of the implanted graft[27]. Also, the importance of mechanical stimuli in osteoinduction and osteoconduction has been stressed in numerous in vitro and in vivo experiments[28-30]. It can be assumed that lack of loading in Ward’s neutral triangle, which may have led to the development of a cystic lesion in the first place, also contributed to the resorption of the implanted bone graft.

In any case, grafting of benign tumors following curettage has been questioned altogether by Hirn et al[31]. They reported on the treatment of 146 cases of large,metaphyseal femoral and tibial benign bone tumors with curettage alone. Successfulconsolidation occurred in 89%. The rest of the cases developed local recurrence and were subsequently treated with further curettage and bone grafting. The authors concluded that augmentation is not necessary for most benign bone defects. It should be noted that, in this study of long bone metaphyseal defects, fractures occurred predominantly in defects greater than 5 cm, whereas calcaneal cysts are considerably smaller.

CONCLUSION

The treatment of an os calcis lipoma should be individualized, depending on the symptoms, the location and the size of the lesion. When surgical treatment of an os calcis lipoma is considered, orthopaedic surgeons should be aware of the possibility of bone graft resorption.