Exercise as medicine to be prescribed in osteoarthritis

Silvia Ravalli, Paola Castrogiovanni, Giuseppe Musumeci

Silvia Ravalli, Paola Castrogiovanni, Giuseppe Musumeci, Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences, Human Anatomy and Histology Section, School of Medicine,University of Catania, Catania 95125, Italy

Giuseppe Musumeci, Research Center on Motor Activities (CRAM), University of Catania,Catania 95123, Italy

Abstract

Key words: Physical activity; Exercise; Training; Chronic disease; Osteoarthritis

INTRODUCTION

The culture of physical activity is not new; a healthy body was vital in prehistoric times, when facility in climbing, running or swimming was essential to escape predators and capture prey. It meant the difference between life and death. Escaping from dangers, hunting and gathering food, as well as building shelters and tools for everyday survival were all activities in which physical effort was essential. As civilisation progressed, hunter-gatherer tribes stopped being nomadic and settled in villages, where the primary resources of sustainment became agriculture and farming.These occupations required fewer physical efforts than those needed to chase animals or climb trees for fruit, but entailed more repetitive movements during the day. Great ancient societies, like the Greeks and Romans, endorsed the pursuit of physical fitness in order to be prepared for war. Epochs of conquests and territorial dominations gave birth to troops of soldiers who were able to conduct long and exhausting battles,where muscle strength, physical resistance and psychological endurance would have decided personal and collective survival. The institution of the γυμνάσιον(gymnasium) and the Olympic Games were symbols of the Greeks’ paramount principle that physical and mental wellness were part of a complete education. In his Memorabilia (371 BC ca.), Xenophon shared a dialogue about exercise that took place between Socrates and his disciples. He concluded with a fascinating thought: “It is a disgrace to grow old through sheer carelessness before seeing what manner of man you may become by developing your bodily strength and beauty to their highest limit”[1].

The XVIII century was the framework in which the Industrial Revolution took place, and marked the passage from manual work to machine-based production. This is when the demand for physical efforts began to decrease, and men became less prone to maintaining fitness in order to be able to perform their work. It is worth mentioning that gymnastics was also a mandated obligation during some historical periods; for instance, during World War II, totalitarian regimes used it to promote Nazi philosophy and, in the Soviet Union, mandatory physical training was required to maintain a productive workforce. As daily life resources became more accessible, a fit body became progressively less important and, nowadays, physical training has become the domain of mainly military and athletic worlds. Leading an active lifestyle implies avoiding sedentary habits and including active mobility as part of a daily routine. This lifestyle does not only refer to sports practice, but also to positive everyday activities ranging from walking to housekeeping. Exercising is part of this concept, and represents a planned activity focused on benefitting both mental and physical health. The type of exercise itself varies depending on the group of muscles or parts of the body involved, the frequency, intensity and duration of movement, the equipment used, and the personal abilities required. Physical training has several purposes: to maintain fitness, reduce weight, boost strength and flexibility, improve mood, treat pathological conditions, and prevent disease. The effects can be evaluated by analysing short-term responses, monitoring a single or acute bout of training, or measuring long-term improvements in a variety of functions after repeated and chronic periods of exercise[2]. Intensity and duration of acute training are involved in the dose-dependent and transient stimulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and sympathetic nervous system. These are responsible for the mobilisation of energy reserves for increasing heart rate and blood pressure, as well as for the improvement of mental vigilance and activation of the immune system. Repeated exercise followed by recovery appears to be associated, in the long term, with adaptive and optimised control of neuroendocrine factors, anti-inflammatory states,increased production of growth factors and enhanced neural plasticity[3]. Acute and chronic exercise effects have been investigated, for example, for their effect on inflammatory states[4], the cardiovascular system[5], the skeletal muscle morphology[6]and cognitive performance[7,8].

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND DISEASES

It is known that a sedentary lifestyle is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality[9]. Although many evidence-based data link physical inactivity to numerous disorders (cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, forms of cancer, obesity), many people do not take it seriously[10]. A high incidence of sedentary habits can shorten life expectancy and raise medical costs of sedentary-related diseases. The World Health Organisation reported in The Lancet Global Health that more than one in four adults globally (28% or 1.4 billion people) is physically inactive[11]. To draw more attention to this alarming problem, the term “Sedentary Death Syndrome” was coined in order to make people aware of the potential consequences of such behaviour. The cause is an imbalance between calories consumed and calories expended, which eventually results in a state of hyperinsulinemia and, thus, adiposity. Overweight or obesity leads to insulin resistance, which could result in diabetes and cardiovascular disorders, as well as several other diseases such as osteoporosis, muscle wasting and general debility[12]. If lack of mobility is responsible for all these concerning health complications, then physical activity could represent a life-saving solution (Figure 1).A study revealed that 150 min of regular exercise a week leads to a decrease in the risk of diabetes, cancer, depression, stroke as well as a 30% reduction in mortality risk[13]. Data in the literature highlight that exercise has a therapeutic role for diseases such as diabetes, obesity, pain, neurological disorders and heart failure[14-17].

Furthermore, physical activity has been reported as an effective intervention in neuropsychiatric conditions; for example, it can improve mood symptoms in depressed pregnant women[18], and may benefit patients with attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder[19]. In a very compelling and detailed review, Pedersen et al[20]analysed a sizeable set of data concerning the role of exercise as a first-line treatment for several chronic diseases. The authors included twenty-six diseases in their analysis, ranging from psychiatric, neurological, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, to musculoskeletal disorders including osteoarthritis (OA), osteoporosis,back pain and rheumatoid arthritis[20].

OA EXPERIENCE

In our research experience, we paid particular attention to the musculoskeletal disorder OA. OA is a prevalent chronic disease of the joints in older people.Pharmacological treatment of OA involves the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioid and non-opioid analgesics, and intra-articular injections of steroids and hyaluronic acid, which may have significant negative gastrointestinal side effects[21].This has led physicians to consider non-pharmacological, regenerative and behavioural treatments[22,23]. Among these, exercise is a good and useful tool to alleviate symptoms of OA and slow its progression[24-26]. The literature has demonstrated that physical exercise has short-term benefits in reducing pain,improving physical function, balance, muscle strength and flexibility[27,28]. Training tailored to improve OA includes anaerobic, aerobic, flexibility workouts and aquatic exercise[29,30]. It is essential to plan a protocol of movement whose type, duration and intensity represents the best approach to induce positive changes within the joint and for the chondrogenesis[31], but does not worsen the pathological condition by excessive load bearing or exhausting exercise[32]. It seems that a combination of aerobic fitness training and strengthening exercises should be optimal to address the spectrum of impairments associated with OA, taking into account the preferences and tolerance of patients in order to maintain a high level of adherence to the exercise program[33,34].

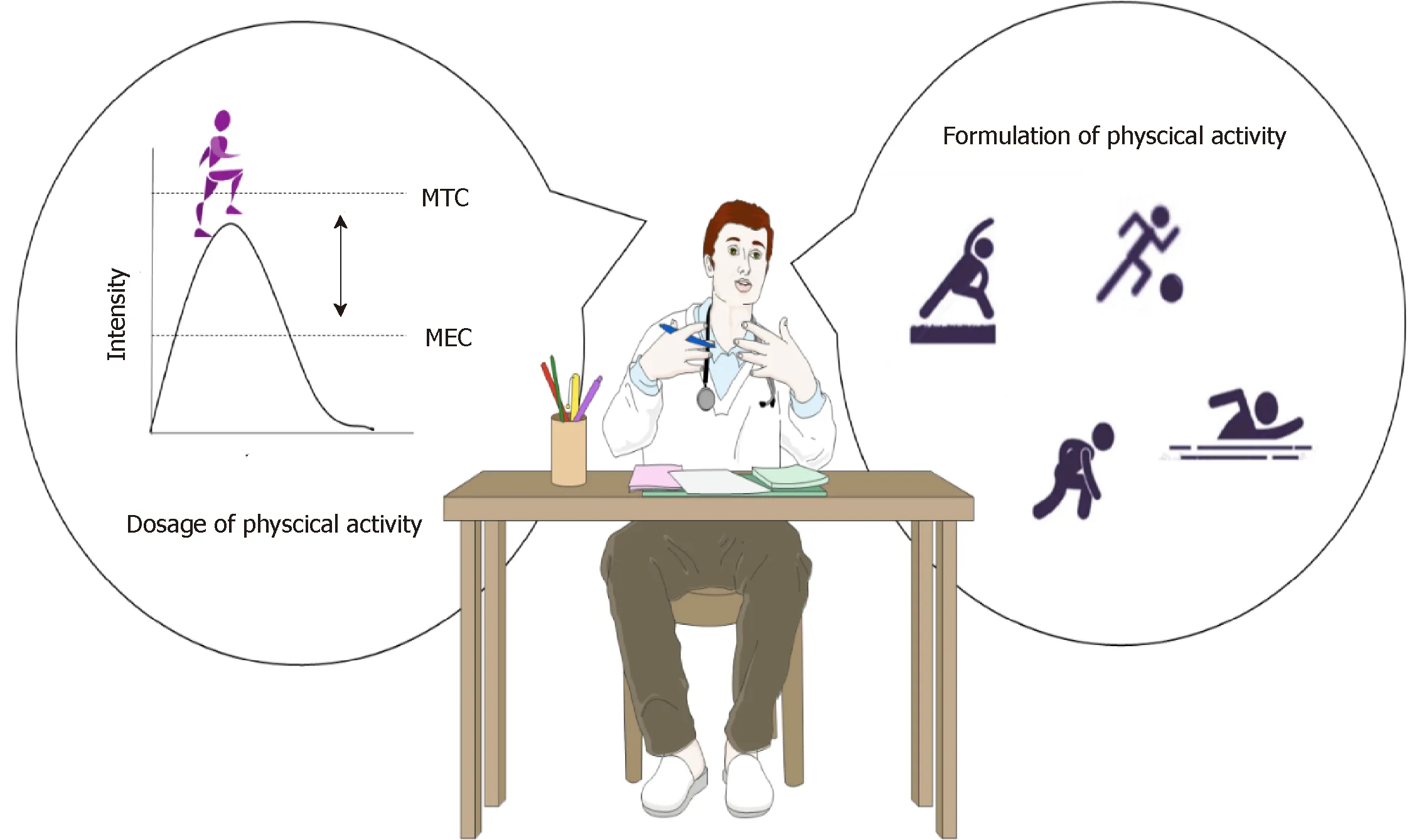

Medicine is more inclined to attempt to cure instead of prevent. As a consequence,human beings are subjected to many chronic illnesses that could have been avoided by observing a few simple health rules. Being physically active should be part of a daily health routine, much like hand washing or wearing a bicycle helmet. It should be prescribed in the same way as pharmacological treatment[35], deciding on the“dosage” and “formulation” for each patient. The “dosage” is calculated to reach a specific level of efficacy that prevents or improves symptoms, but does not result in toxic effects.

It is known that exercise can involve a risk of injury (fractures, muscle strain, torn ligaments), mainly when movements are performed improperly, or the equipment is inappropriate. Strenuous training could impair the immune system, and may be responsible for structural changes of the heart and large arteries, loss of electrolyte balance, and cardiac or respiratory distress[36]. Exercise can influence the blood levels of neurotransmitters, including glutamine, serotonin and dopamine, and misregulation of these could lead to depression, fatigue and confusion. Insomnia can also be caused by exercise-induced cortisol levels. Because of psychological stress about performance and body image, symptoms of anxiety and aggression, eatingdisorders, as well as drugs and alcohol addictions are common in athletes and team players[37]. Specific instructions or “formulations” for specific individuals, undergoing or at risk for such difficulties, are vital (Figure 2). Special categories of patients require special attention: Pregnant women, for example, cannot perform strenuous activities that could put their pregnancy at risk. Children and the elderly are not always able to perform exhausting movements and can, more easily, incur injuries. Importantly,prior to prescribing exercise, chronic or pre-existing pathological conditions, like cardiovascular, metabolic, musculoskeletal and neurological disorders, must first be evaluated.

Figure 1 Clinical conditions negatively affected by sedentary lifestyle and positively affected by active lifestyle.

PROSPECTS

Maintaining awareness of the severe implications of inactivity, as well as the benefits derived from exercise, is crucial. Even more important is to translate into practice what we know from the literature. We suggest that general practitioners consider physical activity seriously, and be prepared to prescribe it knowledgeably. Certified personal trainers could assist in this endeavour, and the government might want to consider incentives like free gym membership. Physicians should not only be knowledgeable in this area of therapy, but should themselves become role models of healthy living.

Figure 2 Prescription of exercise might take dosage and formulation into account. Dosage of physical activity could be ruled by a modified plasma concentration time curve. Formulation refers to the different kinds of training that can be performed. MEC: Minimum effective concentration; MTC: Minimum toxic concentration.

World Journal of Orthopedics2019年7期

World Journal of Orthopedics2019年7期

- World Journal of Orthopedics的其它文章

- Randomised controlled trial of triclosan coated vs uncoated sutures in primary hip and knee arthroplasty

- Platelet-rich plasma for muscle injuries: A systematic review of the basic science literature

- Os calcis lipoma: To graft or not to graft? - A case report and literature review