Multiple rare causes of post-traumatic elbow stiffness in an adolescent patient: A case report and review of literature

Bai-Qi Pan, Jun Huang, Jiang-Dong Ni, Ming-Ming Yan, Qin Xia

Abstract BACKGROUND Joint stiffness after elbow surgery is not a rare complication, and is always accompanied by deformity. The causes of joint stiffness are multiple in different patients, and divided into intrinsic and extrinsic causes. Herein, we report an unusual case of posttraumatic elbow stiffness due to multiple and rare causes.CASE SUMMARY A 19-year-old male was hospitalized with the loss of motion of the left elbow for over ten years. Left limb computed tomography revealed left elbow stiffness with bony block and connection. The patient underwent surgery, and the etiology of joint stiffness was found to be a rare combination of common and uncommon causes. During an 18-mo follow-up period, the patient’s left elbow had normal motion and he was symptom-free.CONCLUSION However, this case combined with multiple and rare causes highlights that the patient with scar physique is likely to be accompanied with more severe soft tissue, nerve contracture, and heterotypic ossification, even during recurrence.

Key words: Post-traumatic; Elbow stiffness; Open surgery; Contracture; Ulnar neuritis;Radial nerve; Scar; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Elbow stiffness is a common complication of elbow trauma, and it has been hypothesized that a 50% reduction in elbow range of motion (ROM) can reduce upper extremity function by as much as 80%. The most common cause of elbow stiffness is soft tissue contracture after initial injury[1,2]. The causes of elbow stiffness in the present case were rare, which included a keloid scar, high tension of the radial nerve,a bony connection and block. There are several treatment options for elbow stiffness including surgical and non-surgical. Treatment selection should be based on history,stiffness severity, complications and progression. In this report, we present a case of post-traumatic elbow stiffness in a teenager with multiple problems for over ten years, which was successfully treated by open surgery.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Left elbow joint extended /flexion disorder for ten years

History of present illness

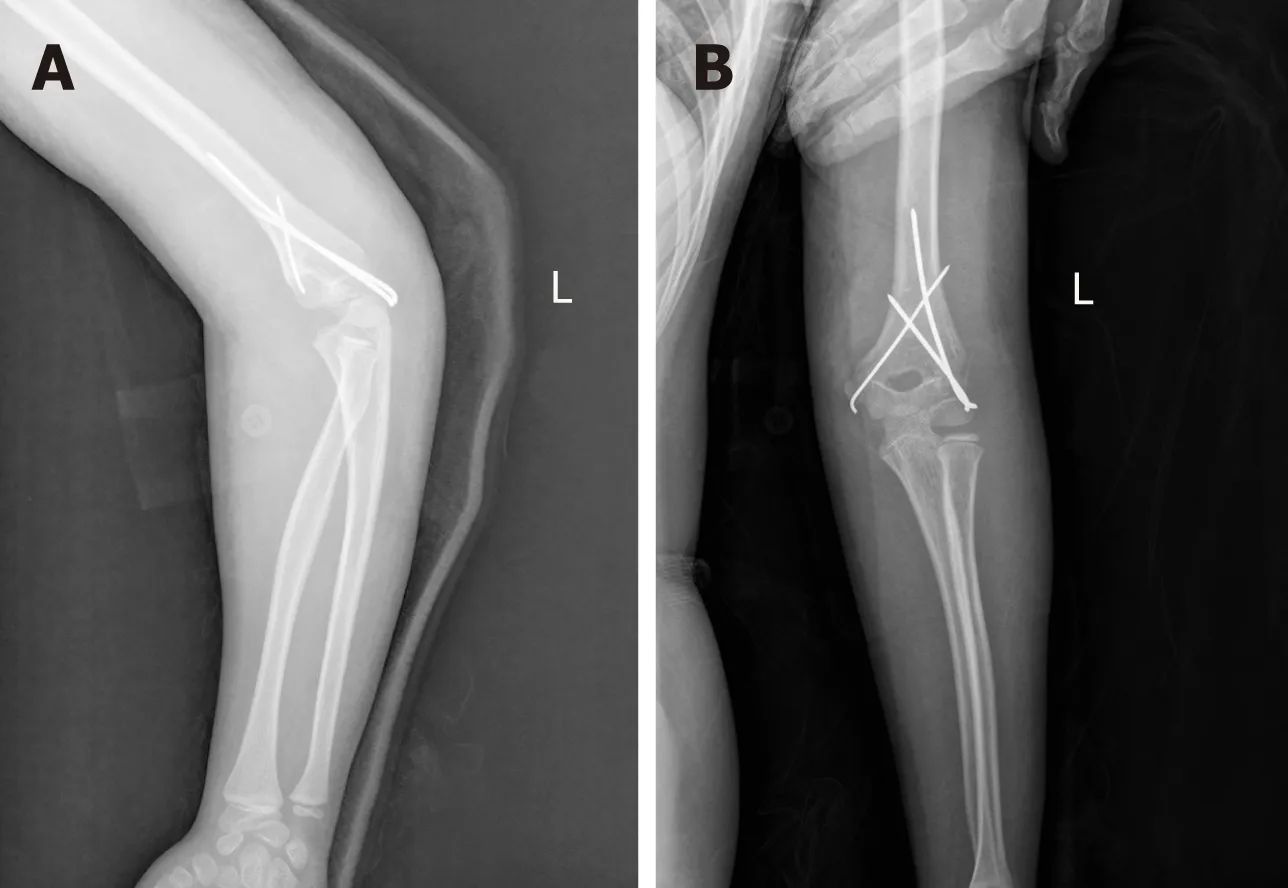

Loss of motion in the left elbow was the only symptom in this adolescent patient. The patient complained of a left elbow joint with extended/flexion disorder for ten years,which was gradually found, since his left supracondylar humerus fracture was treated by open reduction and Kirschner wire internal fixation when he was nine years old(Figure 1, 2). For further diagnosis and treatment, this teenager came to our hospital clinic. With the diagnosis “left elbow joint stiffness”, he was charged in our department.

History of past illness

This 19-year-old right-hand-dominant male patient fell directly on his left elbow while climbing a tree approximately ten years previously. He visited the emergency department for immediate elbow pain and swelling. Radiography showed a left supracondylar humerus fracture (Figure 1). Emergent open reduction and Kirschner wire fixation were performed (Figure 2), and plaster external fixation was applied postoperatively. The splint and Kirschner wires were removed 1 mo later (Figure 3).After surgery, the patient had severe and persistent motion restriction of the left elbow for more than ten years, without receiving any rehabilitation or further treatment due to economic reasons and a misunderstanding of the disease.

Personal and family history

There is no related family history of this patient.

Physical examination upon admission

Upon physical examination, the arc of motion of the left elbow was 35° (flexion in 105-70°) (Figure 4A, B), loss of pronation/supination was 5° and 5°, respectively.

Laboratory examinations

All the laboratory examinations are normal, including routine blood tests, routine urine tests and urinary sediment examination, routine fecal tests and occult blood tests, blood biochemistry, immune indexes, and infection indexes.

Figure 1 Radiography at the time of injury. A: Frontal x-ray of the left elbow; B: Lateral x-ray of the left elbow.

Imaging examinations

Radiography with oblique views (Figure 5A, B), computed tomography (CT) scan(Figure 5C, D) and 3-dimensional CT reconstructions were performed to evaluate the left elbow stiffness.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

(1) Left elbow joint stiffness; (2) Scar physique.

TREATMENT

Considering the deformity caused by elbow stiffness, surgery was performed under general anesthesia. The patient was placed in the supine position with his free left arm on his chest, and a sterile tourniquet was applied. A 15 cm previous incision was present laterally, which was severely scarred around the elbow joint, measuring 4 cm× 2 cm in the widest area (Figure 6D). Following removal of all scar tissue, we decided to use the original surgical incision. We incised the deep fascia along the medial border of the brachioradialis and identified the radial nerve covered by a thin layer of fat between the brachialis and the brachioradialis, uncovering the origins of the extensor carpi radialis longus and brachioradialis along the humeral lateral ridge.When two humeral muscular origins were partially released, the anterior part of the lateral capsule was exposed and resected to reach the coronoid, and a 3 cm × 1 cm ×0.5 cm bony block in the coronoid fossa was subsequently removed (Figure 6B). As flexion of the elbow was still limited, we released the triceps from the posterior humerus to examine the posterior joint capsule. The contracted joint capsule and other fibrous tissue, including callus and scarring in the olecranon fossa, were completely removed. We performed neurolysis of the radial nerve contracture, and released the remaining soft tissue contracture and all bony blocker and muscular reconstruction. The ulnar nerve was detected and the bony connection between olecranon and dorsal humerus was removed via the medial incision, to then rule out ulnar nerve compression (Figure 6A). As no ulnar nerve compression was detected,anterior subcutaneous transposition of the nerve was not performed. However, after these procedures, excessive tension of the contractural radial nerve was still present when the arc flexed to 30° (Figure 6C). Following surgery, the motion arc of the elbow in flexion was 30-145° under manipulation (Figure 4C, D). The incision was closed with full hemostasis and placement of a wound drainage tube. A splint was placed on the left arm.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Celecoxib was prescribed for analgesia, and rehabilitation started from the first postoperative day (Figure 7). One month after surgery, the ROM in the left elbow was completely normal and the patient was pain-free, without evidence of neurological dysfunction. Histopathologic analysis of the scar demonstrated fibrous tissue with tumor-like hyperplasia and hyalinization, and evidence of malignancy was not observed (Figure 6E). Following an 18-mo follow-up, recovery was uneventful and satisfactory.

Figure 2 Radiography after the first operation. A: Lateral s-ray of the left elbow; B: TFrontal x-ray of the left elbow.

DISCUSSION

Elbow stiffness is a common complication of intra-articular fracture, is a frequent disabling condition that interferes with daily activities, and typically occurs in young individuals[3,4]. The general definition of elbow stiffness is: a flexion-extension arc of <100° and/or flexion contracture > 30°. Therefore, if the ROM is less than 30-130°, this would be an indication for surgical treatment by some authors[2,5,6].

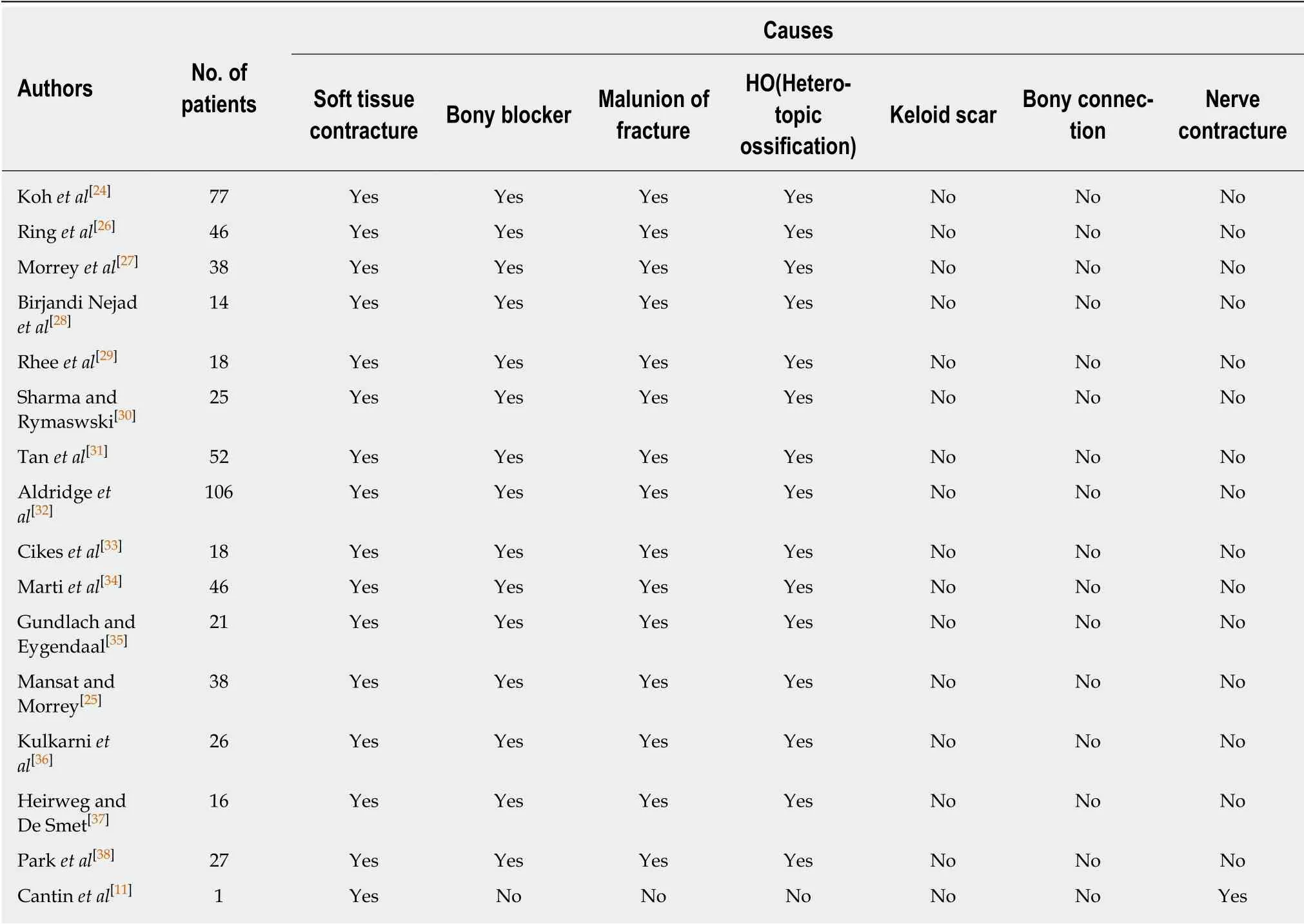

Many causes of elbow contracture have been described, including intrinsic and extrinsic causes - soft tissue contracture, heterotypic ossification (HO), and mal-union or nonunion of a fracture, etc. Other conditions also play a role in the occurrence of elbow stiffness, such as long-term articular immobilization and non-rehabilitation[2].However, our case was rare because of its complicated and special causes, including a keloid scar, high tension of the radial nerve, as well as the bony connection and block(Table 1)[1], in which we find a relationship between the elbow stiffness and scar physique.

There are several treatment options for elbow stiffness, such as open surgery, splint, and arthroscopy. Chronic stiffness is usually managed by arthroscopic or surgical release, with good results (the recovery of ROM can be at least 100°)[1,7,8]. It has also been reported that recovery of elbow stiffness in adolescents was satisfactory after surgical release. The exact intra-operative adjustment of the elbow ROM depends on the specific condition of the patient. The goal of progressive ROM is to increase this motion by lengthening and isolating tissue, not by tearing tissue. Kruse et al[9]reported a technique that maximized elbow ROM by combining lateral and minimal posterior triceps-splinting open elbow contracture release, and the use of a splint with the elbow at 20° of flexion and the forearm neutral at the end of the procedure, which is a safe and effective alternative[10]. However, in the present case, after removing soft tissue contracture and performing complete neurolysis of the left radial nerve surrounding the incision, we found excessive tension of the radial nerve at an elbow flexion of 30° intraoperatively (Figure 6C). No contracture or lesion/deficits were observed in the median nerve and ulnar nerve. Excessive tension of the radial nerve directly affects the surgical outcome of such patients, as this is the limiting factor in the recovery of ROM. The different conditions of these three nerves in the elbow could not be fully explained.

Many studies have correlated outcome with management of the ulnar nerve, but very few studies have reported management of the radial nerve, especially with abnormal tension[1-6,8-38](Table 1). There are also few data in the literature on the radial nerve with excessive traction, as these patients had no neural symptoms. Cantin et al[11]reported their observations in a child with congenital and isolated elbow contracture in flexion who was 16 mo old. They mentioned excessive traction in elbow extension on the neurovascular structures (radial nerve and vascular humeral bundle,particularly the radial nerve), which is the limiting factor in the surgical procedure[11].However, our patient was a teenager with chronic posttraumatic elbow stiffness.According to the structural and biochemical evaluation of the elbow capsule following trauma, disorganization of collagen fiber arrangements, altered cytokine and enzyme levels, and an elevated number of myofibroblasts may also lead to a contracture with high tension of the radial nerve after open surgery for supracondylar humerus fracture via a lateral incision[12-15]. Following this procedure, our patient lived with loss of motion of the left elbow for approximately ten years (the ROM was 70-105° from nine to 19 years of age), and the limitation of ability to distend further exacerbated the problem. Nerves may be relocated away from the influence of a possible irritating callus[16]. A special point of this patient is that the elbow stiffness lasted throughout puberty with scar physique. Thus, under such circumstances,pathological tissue changes during growth and development may lead to growth disturbance (anatomy route or length) and contracture formation in the radial nerve in his adolescent age. The contracture of a nerve and surrounding soft tissue (such as membrane) resulting in over-high tension of the radial nerve leads to limited ROM(Figure 6C). To some extent, we also consider that there may be some relationships between the contracture of nerve with the scar physique (the genetically driven fibrotic scar formation). Thus, the patient with the history of keloid scar formation may be more likely to be accompanied with more severe soft tissue and nerve contracture, causing the elbow stiffness.

Figure 3 Radiography after removal of the Kirschner wire fixation. A: Frontal x-ray of the left elbow; B: Lateral xray of the left elbow.

Safety of the radial nerve should not be neglected when pursuing the desired recovery of ROM during treatment. When the etiology of elbow stiffness is known, in order to increase the left elbow ROM, excessive traction must be reduced. Intraoperatively, the contracture of tissues should be removed as much as possible, and complete neurolysis, athrolysis and the reconstruction of muscular stop points should be performed to reduce over-high tension[17]. Postoperatively, the remaining over-high tension of the radial nerve can be reduced by appropriate rehabilitation. Following successful surgery, an improvement in the ROM in this patient’s left elbow was achieved from 70-105° to 30-145°. We placed a splint on the elbow to obtain flexion of 30° (decided based on individual situation) to protect against over-distension, which ensured that the nerves or vessels were in the safe position of normal tension to avoid injury. Rehabilitation started immediately, allowing gentle elbow ROM in the flexion extension plane without varus or valgus force[18]. Passive motion, physical therapy,splinting and anti-scaring play important roles in the postoperative protocol in such special patients[11]. The elbow ROM gradually improved in our patient with decreased motion tension.

It is inconclusive whether ulnar nerve transposition or decompression is required in such patients. Many studies have shown that it is necessary to perform transposition of the ulnar nerve intraoperatively to avoid delayed-onset ulnar neuritis and other complications[19,20]. Similarly, some studies showed that the ulnar nerve should be mobilized and retracted anteriorly[10]. However, although subcutaneous ulnar nerve transposition is performed during open arthrolysis for posttraumatic elbow stiffness, ulnar neuritis is still an important complication[21]. Ulnar neuritis is associated with deformity or abnormality of the elbow joint. The symptoms become more and more severe if there is a progressive lesion of the ulnar nerve[22]. In addition,it has been shown that transposition had a higher rate of wound complications than decompression, and it had equal preventive effects[20]. Compared with decompression,transposition may be more likely to cause iatrogenic injury resulting in entrapment,neural slippage and other complications[23]. Our patient’s fracture healed well without preoperative nerve symptoms, and no lesions or adhesions were found following prophylactic ulnar nerve neurolysis[18](Figure 6A). Also, the Grade B recommendations for care from the article of Attum et al[1]is that the occurrence of nerve palsy is rare. Therefore, in our opinion, in such cases there is no need for ulnar nerve transposition.

Figure 4 Pre-operative and postoperative flexion/extension range of motion of the left elbow. A: The best position of extension pre-operatively; B: The best position of flexion pre-operatively; C: The best position of flexion postoperatively; D: The best position of extension postoperatively.

The scar contracture was on the elbow joint skin before the third surgery, which severely restricted elbow function, making it difficult to perform preoperative rehabilitation to release soft tissue contracture. The scar formed approximately 2 wk after the first operation, but the reason it extended across the joint may be associated with the following: (1) The patient was fixed in the flexion position postoperatively for too long; (2) No rehabilitation was carried out; (3) The scar physique (genetically driven fibrotic scar formation)[1,24]; and (4) After the first surgery, failed pain control resulted in limited left arm motion. So, in our department, the patient was asked to take part in rehabilitation exercises as soon as possible, and anti-scarring drugs were administered to prevent the same situation from recurring. Thus, aggressive treatment and timely rehabilitation are essential in patients with scar tissue.

In this patient, the incision using the lateral approach was insufficient. The medial bony block and bony connection should be removed to achieve successful arthrolysis via a medial incision, which is used to probe and decompress the ulnar nerve, remove heterotopic ossification, and release the medial collateral ligament or contracted joint capsule[12]. Therefore, we recommend the medial and lateral approaches to optimize treatment outcome in patients with elbow stiffness caused by different factors[17,25].

This adolescent patient is noteworthy, due to the fact that elbow stiffness was not only caused by the intra-articular adhesions, soft tissue contracture and HO, but also by the changes in the contractural radial nerve with excessive tension, keloid scarring of the skin across the joint limiting elbow motion, and the bony block and connection,making treatment challenging. Reducing excessive tension of the radial nerve with complete neurolysis, protecting the nerves or vessels from rupture with maintenance of elbow ROM at 30° to 145° in flexion temporarily after operation, and a regular rehabilitation plan to achieve normal tension of the nerves resulting in safe and optimal elbow ROM proved to be effective in this patient.

Following successful surgery, early rigorous rehabilitation of the left elbow achieved normal activity, and after 18 mo of follow-up, recovery was uneventful and satisfactory (flexion/extension: 135-0-0 degrees for the left elbow). To our knowledge,there are no other detailed reports on such complicated causes in an adolescent patient, and further studies are needed.

CONCLUSION

Upon encountering joint trauma, the patient with a history of keloid scar formation is prone to be accompanied with more severe soft tissue, nerve contracture and even HO, as well as recurrence of joint stiffness. Although the contracture could be reversible, such elbow stiffness in a teenage patient, with rare multiple etiologies, and radial nerve contracture with over-high tension for over ten years, is a rare condition with a possible dire outcome if not managed appropriately. Clinicians should be aware of the pertinent etiology in order to determine the correct treatment option to avoid complications.

Table 1 Causes of elbow stiffness reported in the included studies

Figure 5 Pre-operative radiograph and representative axillary computed tomography image. A: Frontal x-ray of the left elbow, with the arrow pointing to the bone connection; B: Lateral x-ray of the left elbow; C: CT scan of the cross section; D: CT coronal scan, with the arrow pointing to the bony block of the humerus coronoid fossa. CT: Computed tomography.

Figure 6 Detailed images of our surgery. A: Intact ulnar nerve; B: Bony block of the humerus coronoid fossa; C: Radial nerve contracture; D: Scar of skin; E:Pathological section of the scar.

Figure 7 Radiography after the third operation. A: Frontal x-ray of the left elbow; B: Lateral x-ray of the left elbow.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年10期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年10期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Impact of perioperative transfusion in patients undergoing resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases: A population-based study

- Analysis of 24 patients with Achenbach's syndrome

- Risk factors and clinical responses of pneumonia patients with colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumanniicalcoaceticus

- Diagnostic value of two dimensional shear wave elastography combined with texture analysis in early liver fibrosis

- Selective dorsal rhizotomy in cerebral palsy spasticity - a newly established operative technique in Slovenia:A case report and review of literature

- Invasive myxopapillary ependymoma of the lumbar spine: A case report