Development of a biliary multi-hole self-expandable metallic stent for bile tract diseases: A case report

Makoto Kobayashi

Abstract

Key words: Multi-hole self-expandable metallic stent; Malignant biliary stricture; Benign biliary stricture; Hilar biliary obstruction; Distal biliary obstruction; Endobiliary radiofrequency ablation; Case report

INTRODUCTION

In biliary stenting, an uncovered self-expandable metallic stent (UCSEMS) is prone to occlusion due to tumor ingrowth[1-4]. In comparison, when using a covered selfexpandable metallic stent (CSEMS) the side branches of hepatic ducts may become blocked, preventing bile juice flow and making it difficult for a stent to be placed in the hilar area. A specific CSEMS, known as a fully CSEMS (FCSEMS), also has a risk of migration[1-4]. Another type of stent, known as a partially covered SEMS (PCSEMS),was developed with the aim of lowering migration rates compared to CSEMS; however, this is also difficult to place in the hilar area.

In order to resolve these problems, we, together with M.I.Tech Co., Ltd (Pyeongtaek, South Korea), have developed a multi-hole self-expandable metallic stent(MHSEMS; Figure 1) with numerous holes in its cover.

A MHSEMS has a hole in each stent cell on its covering membrane. When the stent is positioned in a junction connected by side branches, bile flows inside the stent through the holes in its covering membrane. Tumors may grow through these holes but may become suppressed due to the size of the ingrowth. As a result of low membrane tension caused by the holes, the placed stent becomes fixed to surrounding tissues and is prevented from migrating. Presently, the MHSEMS is available with two types of hole sizes: small (Figure 1A) and large (Figure 1B).

In addition, a lasso attached to the distal end of the MHSEMS (Figure 1A) is helpful for stent removal. Even if an obstruction by a tumor ingrowth does occur, the silicone cover will protect the surrounding tissue and enhance any ablation effect, such as during endobiliary radiofrequency ablation (RFA), allowing the patient to be a candidate for such treatment. We treated patients with malignant biliary obstruction using MHSEMS.

CASE PRESENTATION

Case 1

Chief complaints:A 74-year-old male presented to our hospilal with jaundice and liver function failure.

History of present illness:The patient had attended the outpatient department of another hospital, and liver dysfunction was identified in a regular check-up.

History of past illness:The patient had a medical history of diabetes and benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Personal and family history:A personal or family history of malignant tumors did not exist.

Physical examination upon admission:On physical examination, icterus of the patient’s conjunctiva was observed. An enlarged liver was palpable in the upper right quadrant. The skin and bulbar conjunctiva were icteric.

Figure 1 Multi-hole self-expandable metallic stent. A: With lasso (small-hole type); B: Large-hole type.

Laboratory examinations:The laboratory findings on admission were as follows:Aspartate trans-aminase (AST) 73 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 61 IU/L,alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 1962 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) 704 IU/L, total bilirubin (T-bil) 8.8 mg/dL, direct bilirubin (D-bil) 5.1 mg/dL, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) 1117.1 ng/mL and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) 32 U/mL.

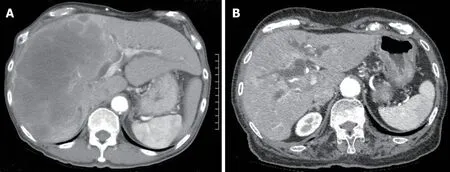

Imaging examinations:Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a sigmoid colon tumor and multiple liver metastases, including a right liver lobe that was almost totally occupied by tumors; the left intrahepatic bile duct was remarkably dilated (Figure 2A).

Case 2

Chief complaints:A 90-year-old female was referred to our hospital by the family doctor because of jaundice.

History of present illness:The patient did not have a history of jaundice.

History of past illness:The patient had a past history of hypertension.

Personal and family history:But she had no personal or family history of malignant tumors.

Physical examination upon admission:On physical examination, the patient’s skin was icteric. A large gall bladder was palpable in the upper right quadrant.

Laboratory examinations:AST 371 IU/L, ALT 418 IU/L, ALP 4273 IU/L, γ-GTP 1367 IU/L, T-bil 9.6 mg/dL, D-bil 6.3 mg/dL, CEA 1.5 ng/mL and CA19-9 39 U/mL.

Imaging examinations:An intrahepatic biliary dilation was detected by computerized tomography (Figure 2B).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Case 1

The patient was diagnosed with obstructive jaundice caused by a sigmoid colon cancer and multiple liver metastases.

Case 2

The patient was diagnosed with obstructive jaundice caused by hilar cholangiocarcinoma.

TREATMENT

Case 1

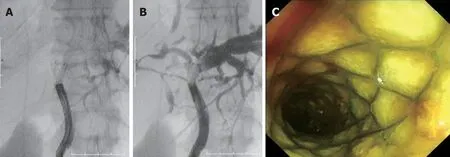

We selected MHSEMS to keep the left bile duct free from invasion by the right lobe tumor, the presence of the latter meaning the right liver lobe was not functioning(Figure 2A). A MHSEMS was placed from the left bile duct to the common bile duct(CBD; Figure 3A and B).

Case 2

We selected a MHSEMS because of an expectation of reduced tumor ingrowth. The patient had a MHSEMS placed from the right hepatic duct to the common bile duct to protect the duct from ingrowth and to keep the bile duct patent from left and

Figure 2 Computerized tomography images. A: A large metastasis in the right liver lobe; B: Intrahepatic biliary dilation.

Figure 2 posterior branches (Figure 4A).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1

After MHSEMS placement, T-bil decreased from 11.9 mg/dL to 1.3 mg/dL. Nine days after stent placement, cholangiography was undertaken using a direct peroral cholangioscope with a slim endoscope. An intrahepatic bile duct branch was successfully filled with contrast material from a slim endoscope through the stent’s holes. The metallic mesh was found not to be buried in tissue but was fixed to the wall because of the low tension of the covering membrane (Figure 3C). Thirty-six days after MHSEMS placement, the patient died due to cancer. However, the total bilirubin level had been kept almost within normal range after stent placement.

Case 2

After MHSEMS placement, T-bil decreased from 9.6 mg/dL to 1.1 mg/dL. However,after 8 mo, the stent became obstructed by tumor ingrowth. We treated the patient by ablation therapy and a monopolar catheter (Figure 4B). After ablation therapy, a tube stent was placed and liver function improved. The patient was transferred to another hospital in order to receive palliative medicine.

DISCUSSION

Most biliary stents may be broadly classified into two types: UCSEMS and CSEMS.An UCSEMS can be placed in a hilar lesion, but has a risk of ingrowth. In contrast, the use of a CSEMS has the disadvantage of the chance of branch obstruction occurring.Another type of stent, a PCSEMS, may reduce the risk of migration; however, it is also unusable in the hilar region. To date, these have been the main types of stents available for the treatment of biliary strictures.

In various meta-analyses undertaken, little difference was observed between the use of UCSEMS and CSEMS in terms of stent failure and patient mortality. However,stent ingrowth and migration rates differed for these two types of biliary stents. The rate of tumor ingrowth for UCSEMS was significantly higher than the rate for CSEMS.In contrast, the stent migration rate was higher for CSEMS compared with UCSEMS.In addition, meta-analyses revealed a lack of difference in the overall complication rate[1-4]. Overall estimates by meta-analyses also revealed a lack of substantial difference between FCSEMS and PCSEMS[1]. Compared to UCSEMS, PCSEMS did not prolong stent patency in unresectable malignant distal biliary obstructions[5].Identifying a need for a new type of stent, we therefore collaborated with M.I.Tech to develop a MHSEMS. This stent has many holes in its cover designed to prevent not only blockage of bile duct branches, but also stent migration.

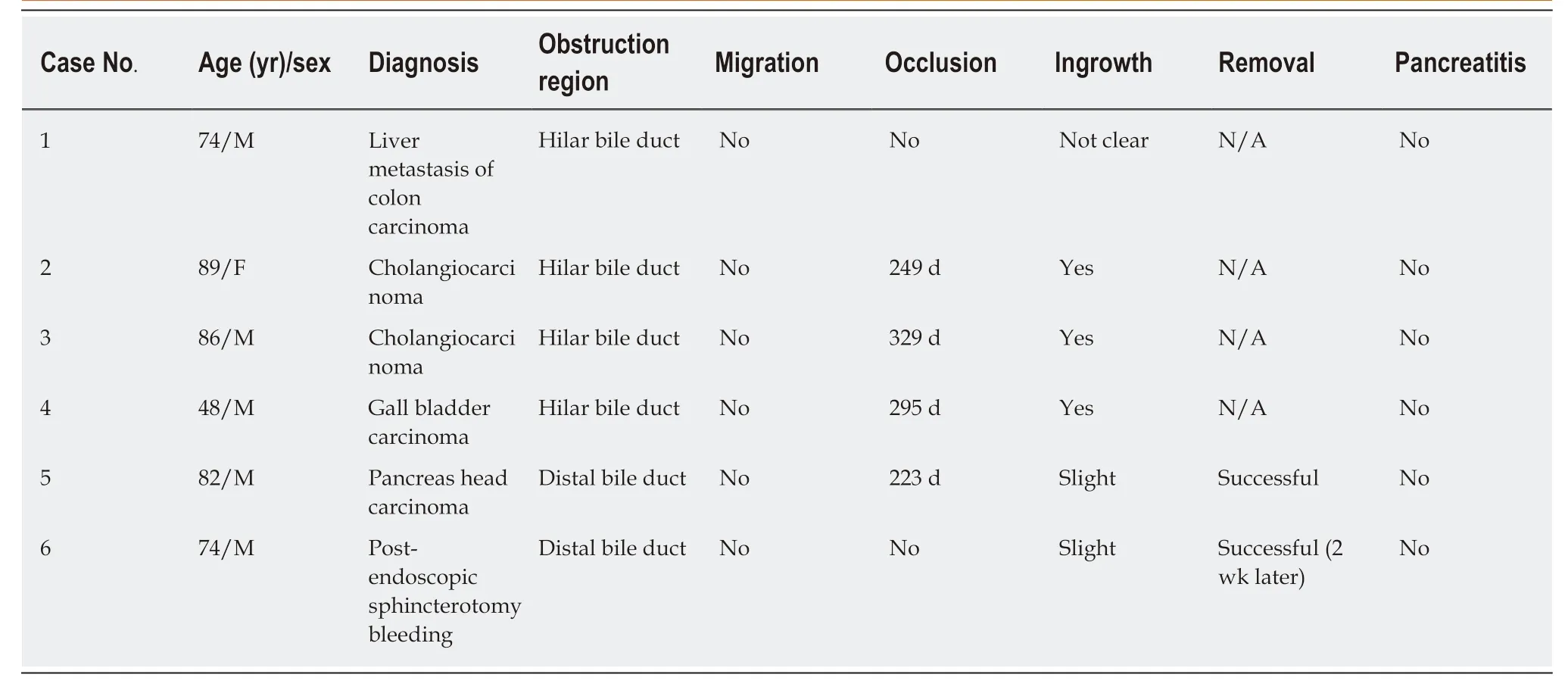

We treated six cases showing bile duct obstructions with MHSEMS, and had a 100% success rate for stent deployment (Table 1). Stent patency was also 100%successful (Table 1). In addition, jaundice improved in all patients with a malignant stricture, while complications such as pancreatitis, bleeding and cholangitis did not occur. The mean patency duration was found to be 274 d.

Figure 3 Cholangiography via a direct peroral cholangioscope. A, B: The right bile duct was visualized by contrast material through the stent openings; C: After cholangiography, the metallic mesh was not found buried in tissue but fixed to the bile duct wall.

The MHSEMS has been designed with a lasso at its distal end for removability. In the event of the stent obstructing a bile duct branch and causing cholangitis, it can be removed very early after placement because the cover prevents the stent from becoming buried in tumor tissue.

In cases of benign strictures, the MHSEMS can also be easily removed. For example,MHSEMS were inserted in six mini pigs with artificial hilar biliary strictures; after 4 wk, all stents were easily and safely taken out[6]. For one of our studied cases, a MHSEMS was used for uncontrolled post-endoscopic sphincterotomy bleeding and was safely removed after 2 wk.

It is thought that endobiliary RFA is safe and has efficacy for unresectable malignant bile duct obstructions[7,8]. Pertinently, the successful and safe use of UCSEMS for occlusive endobiliary RFA has been reported[9,10]. With the use of MHSEMS, endobiliary RFA may become an even more effective and secure treatment since the insulated silicone cover can protect surrounding tissue from thermal injury.

The larger hole size of the MHSEMS is characteristic of an UCSEMS, but the smaller hole size and number is more typical of a CSEMS. With regard to preventing migration and ingrowth in a distal bile duct malignant stricture, it may be that the hole size and number need to be reduced. It would be ideal if hole size and number are adapted to the condition of each stricture.

CONCLUSION

In summary, MHSEMS may be considered a hybrid-type stent, with characteristics that fall between those of UCSEMS and CSEMS. Thus, MHSEMS may be regarded as a promising new treatment option for benign and malignant bile duct strictures.

Table 1 Characteristics and outcomes of six cases treated with multi-hole self-expandable metallic stents

Figure 4 Cholangiography of a multi-hole self-expandable metallic stent and ablation therapy. A: The left bile duct was visualized by contrast material through the stent openings; B: Ablation therapy by monopolar catheter and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年11期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2019年11期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Huge primary dedifferentiated pancreatic liposarcoma mimicking carcinosarcoma in a young female: A case report

- Multiple synchronous anorectal melanomas with different colors: A case report

- Paraneoplastic leukemoid reaction in a patient with sarcomatoid hepatocellular carcinoma: A case report

- Lupus enteritis as the only active manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report

- Application of pulse index continuous cardiac output system in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: A prospective randomized study

- Clinical features of syphilitic myelitis with longitudinally extensive myelopathy on spinal magnetic resonance imaging